Abstract

Pulsed laser deposition facilitates the epitaxial deposition and growth of TiO2 at low temperature on hot substrate. In this study, nanosized nitrogen-doped TiO2 thin films were deposited on fabricated alumina disc-shaped and glass substrates. Textural properties of the fabricated disc and alumina disc-supported TiO2 were investigated using N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), X-ray diffraction and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. FESEM showed the presence of single crystals of TiO2 on the alumina disc. FTIR showed the presence of octahedral TiO2 and different hydroxyl groups on the surface which is responsible for the photoactivity and also showed the functional groups adsorbed on the catalyst surface after the photocatalytic degradation. The concentration of 2-chlorophenol and the photo-redox intermediate products as a function of irradiation time was determined. The concentration of the produced chloride ion during the photocatalytic degradation was determined by an ion chromatography. The results showed that the photocatalytic activity of the catalyst decreased upon cycling. The obtained results were compared with nanostructured TiO2 supported on glass substrate. Higher efficiency of 100% degradation was achieved for TiO2/Al2O3 catalyst, whereas about 70% degradation of 2-CP was achieved using TiO2/glass. Different photointermediates of 2-CP degradation have been identified for each cycle. The difference of intermediates is supported by the adsorbed fragments on the catalyst surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the rapid depletion of freshwater resources, there is an increase in the number of research in this area to meet the needs of pure drinking water for everyday activities. There has been a marked increase in the number of research groups working in the field of desalination and wastewater treatment. One of the main components of waste materials in the oil industry is aromatic compounds. High-temperature coal conversion, petroleum refining, plastics, resins and other industries are the most common producing these compounds. These compounds cause serious environmental problems because the biological degradation of these compounds occurs very slowly or not at all (Mukherjee et al. 2007). Various methods such as adsorption (Banat et al. 2000; Dutta et al. 2001), chemical oxidation (Wu et al. 2000; Hu et al. 2001) and coagulation sintering (Özbelge et al. 2002) were used to remove these compounds from wastewater. Intensive research work has been done on the removal of phenolic compounds using activated carbon as adsorbent (Tancredi et al. 2004; Mohanty et al. 2005; Namane et al. 2005; Tanthapanichakoon et al. 2005). The regeneration of activated carbon by thermal means causes additional cost and its adsorption capacity decreases with time. These treatment schemes also provide fairly reliable effectiveness on pollutant removal. However, the chemicals and adsorbents used and the solid residues (sludge) generated are unavoidable disadvantages of these treatment practices. For decades, scientists and engineers have been seeking innovative technologies that can be applied to degrade chlorinated compounds containing refractory organic pollutants, particularly with low or no chemical usage and sludge generation. The advance of photochemical processes has made the decomposition of synthesized refractory organics sustainable, especially with the advent of semiconductor photocatalysts (Tamon 2005; Chen and Mao 2007).

Heterogeneous photocatalysis employing titanium dioxide (TiO2) has been successfully applied to degrade hazardous compounds in air and water (Serpone et al. 2012; Ibhadon and Fitzpatrick 2013; Binas et al. 2017; Ameta et al. 2013; Muneer et al. 2005). Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is of interest because of its high photocatalytic activity, low cost and high chemical and thermal stability. However, due to its large band-gap of about 3.2 eV (Daneshvar et al. 2006) it can be activated only by UV radiations which make up only a small fraction of the solar spectrum.

One of the main advantages of the photocatalytic oxidation process is that it can be effective enough to treat many contaminants in a single step process. Large mineralization can cause a large number of contaminants under mild reaction conditions. Moreover, it is possible to run the process under solar radiation (Sun et al. 2009).

Most of the research on photocatalytic oxidation reactions was carried out using colloidal solutions of TiO2 molecules in an artificially contaminated aqueous solution. The main obstacle to this method is the difficult and costly filtration step of small catalyst molecules and their recycling. Several catalyst supports have been proposed, such as quartz, silica, various types of glasses, ceramics (Balasubramanian et al. 2004), activated carbon (Mukherjee et al. 2014), fiberglass (Athanasekou et al. 2015), stainless steel (Velo-Gala et al. 2013), etc. In addition, mild steel can also be used as a catalyst for photosynthesis (Rachel et al. 2002). The synthesis of TiO2 photocatalyst films was performed using various methods such as thermal oxidation of metals (Truyen et al. 2006), sol–gel (Deguchi et al. 2001), dipping coating (Chin et al. 2010), electroporation sputtering (Su et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2002), metallic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) (Mahmoud et al. 2013) and pulsed laser deposition (PLD) (Fujimura and Yoshikado 2003; Khalifa and Mahmoud 2017; Farkas et al. 2008; Suda et al. 2004, 2005; Zhao et al. 2008; Sato et al. 2009). A good adhesion thin layer with good mechanical rigidity, substrate adhesion and high surface area can be obtained through the PLD process. (Socol et al. 2010). Furthermore, PLD has the advantages of transferring materials from the target to the substrate in an equal manner (Socol et al. 2010), operating at different pressures and temperatures, and flexibility in the choice of substrate materials. Numerous studies have succeeded in manufacturing-supported TiO2 combinations supported on glass panels in a PLD method. However, much of this research has focused on either fabrication or characterization of catalysts and has not paid more attention to its photocatalytic properties.

In the present study, we focus on preparing immobilized nitrogen-doped TiO2 thin film prepared using pulsed laser deposition technique on a novel fabricated support as γ-alumina disc and evaluating these films for the environmental applications using 2-chlorophenol degradation as an example pollutant. We have compared the photocatalytic activity of TiO2/Al2O3 with TiO2 thin film supported on glass substrates.

Experimental

Preparation of the alumina disc and PLD-deposited TiO2 thin films

The alumina disc was prepared by adding 2 g of polymethylmethacrylate (Fig. 1) dissolved in 200 ml acetone to 4 g of γ-alumina powder (0.45 µm size) while constantly stirring the solution. The acetone was then evaporated at room temperature. The produced powder was compressed under a pressure of 1.76 kg cm−2 for 10 min.

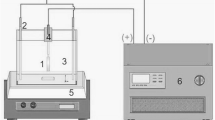

The obtained disc of 2.5 cm diameter was used as a substrate. TiO2 thin films were deposited by PLD technique using KrF excimer pulsed laser PLD system (wavelength λ = 248 nm). A turbomolecular pump and mechanical pump were employed in series to maintain system base pressure at 1.3 × 10–7 Pa. Buffer gas of 5 (Ar):4 (O2):1 (N2) by volume was used during the deposition. Two 500-W halogen lamps were used as radiative heat source to control the substrate temperature from room temperature to 673 K. The substrate temperature was controlled below the anatase-to-rutile phase transition temperature. The rotating target disc was composed of anatase-phase TiO2. Target rotation speed was kept at 15 rpm. The incident laser beam maintained a 45° angle to the target surface. Laser pulse frequency was set at 15 Hz with a calculated laser beam flux of 1.8 J/cm2. The deposition rate of TiO2 thin films was about 0.09 Å per laser pulse. Alumina disc or glass sheets with the same dimensions were used as the substrate for deposition. Prior to the deposition, all substrates were cleaned ultrasonically in pure acetone solution and triple rinsed with deionized water. The target was ablated under partial nitrogen and oxygen reactive atmosphere on alumina disc by PLD technique. Depositions were carried out at buffer gas pressures of 33 and 100 Pa for each substrate.

Characterization of alumina disc-supported TiO2

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the synthesized samples were measured using Quantachrome NOVA apparatus at 77 K after degassing under vacuum at 120 °C for 18 h Particle size distribution was calculated from Barrett, Joyner and Halenda (BJH) method using adsorption branch of the isotherm. Surface morphology was studied using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; JEOL-JSM-5410). X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded using X-ray diffractogram (XRD; Bruker D8) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Fourier transform infrared measurements were performed using infrared spectrophotometer adopting with KBr technique (FTIR; ATI Mattson 936 model Genesis series).

Photolysis and photocatalysis of 2 chlorophenol (2-CP)

500 ml of deionized water containing 100 ppm of high-purity 2–CP (Aldrich) was subjected to UV irradiation using 6 W lamp at a wavelength of 254 nm. All photodegradation experiments were conducted in a batch reactor. UV lamp was placed in a cooling silica jacket and placed in a jar containing the polluted water. The catalyst disc was supported in the solution with a glass holder at a controlled reaction temperature of 25 °C during the experiment. At different irradiation time intervals, small volume samples of the irradiated solution were withdrawn for the analysis using high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC; PerkinElmer series 200) equipped with photo-diode-array detector and C18 column. The mobile phase was acetonitrile/water (60:40) injected at a rate of 1.0 ml min−1. The chloride ion produced during the degradation process was determined using an ion chromatograph (Dionex-pac).

Results and discussion

Structure and composition of the fabricated TiO2 thin film/support photocatalyst

Figure 2a, b shows the adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution of the alumina disc and TiO2 thin film/alumina disc. The isotherms were typical type IV, characteristics of well-developed mesoporous materials. The pore size distribution was narrow, ranging from 3.8 to 19 nm. The surface area SBET of the alumina disc was 32.6 m2/g, while after the deposition of TiO2 the surface area increased sharply to 92.46 m2/g. The increase in surface area might be due to the nanostructure morphology of the deposited film and the porosity generated from the decomposition of the binding polymethylmethacrylate polymer to carbon dioxide gas and evaporated water during the deposition of the TiO2 at 400 °C. The obtained pore volume of 0.55 cm3/g of the TiO2 thin films/alumina disc was significantly high, compared to that reported by other research groups (Nakamura et al. 2005; Lin et al. 2008; György et al. 2005). The large pore volume could be attributed to the decomposition of the polymer which occupied different positions in the disc.

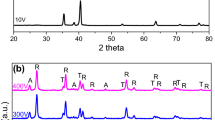

Figure 3 shows the XRD pattern of alumina disc before and after TiO2 deposition. The peaks from bare alumina disc correspond to γ- Al2O3 phase. The absence of wide-angle reflections of TiO2 is attributed to its high dispersion on alumina surface and small size (Choi et al. 2006). The absence of any TiO2 peaks could also be assigned to the weakness of Ti–O bond. The undetected diffraction peaks of TiO2 phase might be due very low intensity peaks due to either the formation of ultrathin films and/or low crystallinity of the deposited films.

Figure 4 shows the surface morphology of the alumina disc before and after TiO2 deposition. The presence of octahedral single crystals after depositing TiO2 on Al2O3 surface is easily visible in Fig. 4b.

Figure 5a, b represents the FTIR spectra of the Al2O3 disc-supported TiO2 before and after using it as photocatalyst for the photocatalytic degradation of 2-CP. Figure 5a shows that Al2O3 disc-supported TiO2 exhibited a complex spectrum containing a set of low-intensity bands in the (OH) region. Three main bands were observed at 3807, 3750 and 3689 cm−1. These three bands are characteristic for surface hydroxyl groups (OH) stretching modes of different types (Stathatos et al. 2004). The activity seems to have a direct correlation with the amount of O–H bonds on the surface. This is because the presence of hydroxyl groups on the surface might inhibit the hole (in the valence band)–electrons (in the conduction band) pairs recombination (Bosc et al. 2003). The characteristic effects of H-bonding of the O–H band are clearly detectable in the low frequency region at 960 cm−1 (Tsoncheva et al. 2008). This kind of surface vibration has already been observed by [Morterra and Magnacca[ 48] on alumina samples and by Hadjiivanov et al. (Zhang et al. 2010) on TiO2 (anatase) samples.

Figure 5a shows two absorption peaks, observed at 1623 and 3441 cm−1. The former is attributed to the N–H bending band and the latter to the N–H stretching band formed by the effect of nitrogen doping. An absorption peak appeared at 747 cm−1 which could be assigned to Al–O bond of Al2O3. Absorption peak at 561 cm−1 shows stretching vibration of Ti–O–Ti octahedral structure (Morterra and Magnacca 1996; Hadjiivanov et al. 1994; Dai et al. 2003) and the peak at 621 cm–1 is assigned to a Ti–O vibration, where the oxygen atom is in the non-binding state. A sharp intense peak at 1731 cm−1 appeared due to the presence of carboxylic acid stretching vibration. The band at 950 cm−1 is due to the O–H bending of carboxylic acid. The band at 1218 cm−1 could be attributed to the C–O of carboxylic acid stretching vibration. Absorption band at 2366 cm−1 is characteristic for the produced CO2 during the decomposition of polymethylmethacrylate (Milanović et al. 2010).

Figure 5b shows the functional groups adsorbed on the catalyst surface during the photocatalytic degradation of 2-CP. Figure 5b exhibits the characteristic band (shoulder) at υ = 800 cm−1 due to C–Cl stretching vibration (Morgado et al. 2007). A strong carbonyl peak was observed at 1729 cm−1 which attributed to the carbonyl stretching vibration. Peak at 1829 cm−1 corresponds to the vibrational frequency of CO of aliphatic acid chloride. The band at υ = 2946 cm−1 corresponding to the C–H stretching vibration of CH3 or CH2. The band at 1452 cm−1 indicate the presence of C = C stretching vibration for aromatic ring. The vibration band at 1392 cm−1 indicates the presence of the phenolic OH in plane bending. The band at 1062 cm−1 corresponds to C–H stretching vibration of aromatic ring. The peaks at 2337 and 2362 cm−1 seem to reflect the supramolecular structure expressed by hydrogen bonding and intramolecular hydrogen bonds (Ennis and Kaiser 2010).

Figure 5b also shows the decrease in intensity of the different hydroxylation modes which indicates the sharing of OH in the photodegradation process. The disappearance of the peaks at 1623 cm−1 and diminishing of the intensity of 960 cm−1 peak after the degradation process indicate that N–H bending mode and C–O group play an important role in adsorption process which can serve as adsorption sites. The disappearance of the characteristic band for bridging oxygen Ti–O–Ti after the photodegradation indicates that the bridging oxygen plays a major role in this process. These oxygen vacancies act as the adsorption sites.

Direct photolysis

2-CP shows slower photolysis under direct irradiation; the concentration decreased according to a first order rate law. Up to 70% degradation was achieved after 3 h irradiation time (Fig. 6). The pH of the solution decreased during the run from 6.5 to 5.5. This might be due to the formation of carbonic acid and/or more acidic intermediates. Catechol was detected by HPLC analysis as the main aromatic intermediate under these conditions. The same finding was also previously reported (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012; Hishikawa et al. 2017; Lukes et al. 2005). This confirms that an efficient cleavage of the C–Cl bond occurs from the electronically excited state of 2-CP produced by direct light absorption.

Photocatalytic degradation in the presence of TiO2

Upon using N2-doped TiO2 thin films supported on the glass substrate, the 2-CP degradation under irradiation was clearly proceeded slower than TiO2/Al2O3 (Fig. 6). This could be attributed to the scattering of light by the glass substrate. Moreover, the quick recombination of photogenerated electrons (e_) and holes (h+) also decreases the photocatalytic efficiency of TiO2.

2-CP photocatalytic degradation was investigated under irradiation in the presence of un-supported TiO2 on alumina disc. The 2-CP concentration decreases to reach 59.24 ppm within 10 min after which the concentration remained almost unchanged, up to 180 min. The 2-CP concentration decreased down to 55.7 ppm after 30 min of irradiation and remains unchanged till 180 min irradiation time (Fig. 6). There was no intermediate detected by HPLC.

In the presence of TiO2 thin film supported on alumina disc, complete degradation was achieved after 60 min of irradiation time. It was reported that chlorophenols did not suffer degradation on γ-Al2O3 whether in the dark or under light. Only minor amount of chlorophenol was adsorbed on γ-Al2O3 with cleavage of the C–Cl bond (Li Puma and Yue 2002). Al2O3 has already been reported to be inactive for the photocatalytic degradation of chlorophenols. On the other hand, a good dispersion of TiO2 on γ-Al2-O3 is expected in the area of low TiO2 content. The acidic property of the γ-Al2-O3 could increase the surface acidity of TiO2 and promote the photocatalytic rate (Li Puma and Yue 2002).

It can be concluded from the above-obtained results that the critical steps of the heterogeneous photocatalytic process are basically five steps. The first step is to transfer the reactants in the contaminated water to the catalyst surface. The subsequent adsorption step of the reactants on the catalyst surface is followed by photoreaction in the adsorbed phase and desorption of the final product. The last step is to move the products to the liquid phase. In general, the photolysis of an organic compound is assumed in the presence of a photocatalyst according to the following mechanisms:

When the catalyst is exposed to a higher energy light than the band gap energy, the electrons are promoted from the valence range to the conduction range. As a result, an electron hole pair is formed (Kiwi and Grätzel 1987)

where ecb-· and hvb+ are the two negatively charged electrons in the conduction bar and the positively charged holes in the valence range, respectively. When the electron–hole (e–h) pair is formed by ultraviolet radiation, the activation energy is large enough to excite the photogenerated electron (e_) from the HOMO TiO2 band (3.2 eV) in the LUMO Al2O3 band (> 5.0 eV). However, the photogenerated hole (h+) in TiO2 cannot actively convert the Al2O3 band region. Therefore, the reconstitution of the light-generated electron (e_) and the aperture pair (h+) is opposed by separation. In fact, this proposed phenomenon can be attributed to the degradation of 2-CP photocatalyst. Each of these entities (e_ and h+) can migrate and perform oxidation–reduction reactions with other species on the catalyst surface. In most cases, hvb+ and ecb− can easily react with surface-bound H2O and O2 to produce OH roots, producing an anoxic superoxide anion, respectively (Chen et al. 2005; Konstantinou and Albanis 2004)

This reaction prevents the recombination of the electron and the hole which are produced in the first step. The •OH and O2− produced in the above manner can then react with 2-CP to form other species and is thus responsible for the oxidation of the pollutant.

Stability of TiO2/Al2O3 catalyst

Photocatalytic degradation experiments of 2-CP were carried out repeatedly using the same prepared TiO2/Al2O3 catalyst to examine its stability (Fig. 7). It can be observed that after three repeated cycles, the catalyst activity decrease toward the degradation process of 2-CP degradation, the percentage degradation changes from 98 to 70%. However, a relatively significant decrease of degradation was observed after the third cycle (74%). This could be attributed to several reasons; i) gradual conglomerate of the intermediates species on the disc after third cycles; ii) the bonding of the adsorbed pollutant onto the support material may hinder the availability of active sites, which therefore reduced the 2-CP degradation efficiency, and iii) the formation of degradation intermediates of 2-CP that are resistant to UV radiation. Such intermediate compounds could absorb more in the UV region or they could adsorb on the catalyst surface and shift the reaction pathway or inhibit the degradation rate of 2-CP.

Aromatic intermediates

Catechol (CT) was the main aromatic intermediate generated under our condition. CT was detected during 2-CP degradation under irradiation of both UV/TiO2 and UV + TiO2/Al2O3 catalysts. Since CT does not form in high yield under photolysis and photocatalysis using TiO2 thin films supported on glass sheet, the CT substitution by OH groups is not expected to occur with high yield through ·OH radical attack at the semiconductor–water interface due to the fast recombination between holes and electrons. Indeed, CT concentration profiles under light + TiO2/Al2O3 were progressively higher (Fig. 8). It is higher than that detected under light irradiation in the absence of photocatalyst and when using TiO2 supported on glass substrate. The sudden disappearance of CT using TiO2/Al2O3 could be attributed to the strong adsorption of CT on the alumina surface.

CT is known to strongly adsorbed on TiO2 and Al2O3 (Mahmoodi et al. 2006), forming long wavelength absorbing complexes. FTIR study shows that the disappearance of the band at 561 cm−1 (Ti–O–Ti bond), after the degradation process may probably be due to participation of Ti surface atoms in the formation of CT complex.

The undetection of CT in the second cycle in water even if it forms at the semiconductor–solution interface, might be due to the its rapid photocatalytic degradation directly at the interface and/or it does not transfer to the solution. Hydronium ions produced when CT adsorbs should likely contribute to a pH decrease and to ionization of available hydroxyl surface groups which led to desorption of the intermediate from the surface of the catalyst (during the third cycle).

During the third cycle, the photoactivity of the TiO2 thin film decreased (Fig. 6). The concentration of 2-CP decreased to reach 70% after 180 min of irradiation time. However, there was one aromatic intermediate present in the irradiated water. This intermediate was suggested to be 1, 2, 3, trihydroxybenzene through the injection of authentic sample of pure material. The formation of this intermediate may be due to the ionization of hydroxyl groups of the surface during desorption of the intermediate from the surface after induction period of 15 min.

Chloride ion concentration in the irradiated water

Figure 9 shows the chloride ion concentration during the direct photolysis and photocatalytic degradation of 2-chlorophenol using Al2O3 disc-supported TiO2. During the direct photolysis, the chloride ion concentration continuously increases with 2-CP degradation up to 90 min of irradiation time reaching about 15 ppm. Upon increasing the irradiation time up to 140 min, the chloride ion concentration did not show a significant change. During the photocatalytic degradation using the fresh TiO2, the chloride ion concentration increases to reach 27.3 ppm after 140 min of irradiation time in the first cycle. While the chloride ion concentration is 23.9 ppm, it reaches 21.49 ppm in the third cycle. The decrease in the chloride ion concentration upon the reuse of the catalyst might be due to the adsorption of 2-CP and other intermediates on the catalyst surface which hinders the cleavage of C–Cl bond. The roles of the chloride ion in the whole process are; (i) adsorption on the catalyst surface, (ii) the ability to act as scavengers of hydroxyl radicals (Emam 2012) and (iii) chloride ion absorption of UV light. All of the above mentioned effects could considerably decrease the 2-CP degradation rate.

Conclusions

TiO2 thin films photocatalysts were successfully deposited by PLD on alumina disc. The prepared catalysts showed a high activity toward photocatalytic degradation of 2-CP in water. A concentration of 100 ppm was completely mineralized within one hour using fresh catalyst. The prepared catalyst showed a gradual decrease in its catalytic activity upon reuse. Our study showed that the photoactivity of the Al2O3-supported TiO2 was much higher than that of TiO2 thin film supported on glass substrate. The decrease in photoactivity of Al2O3 disc-supported TiO2 could be attributed to the high concentration of chloride ion in the irradiated solution. The chloride ion could be adsorbed on the catalyst surface (as indicated from FTIR), act as scavenger of the OH and also absorb UV radiation. Different pathways and mechanisms of 2-CP degradation have been suggested for each cycle. The difference of each mechanism is supported by the adsorbed fragments on the catalyst surface.

References

Ameta R, Benjamin S, Ameta A, Ameta S C (2013) Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants: a review. In Materials Science Forum 734: 247–272. Trans Tech Publications Ltd.

Athanasekou CP, Moustakas NG, Torres SM, Martínez LMP, Figueiredo JL, Faria JL, Silva AMT, Jose. Rodriguez MD, Romanos GE, Falaras P, (2015) Ceramic photocatalytic membranes for water filtration under UV and visible light. Appl Catal B 178:12–19

Balasubramanian G, Dionysiou DD, Suidan TM, Baudin S, Laine JM (2004) Evaluating the activities of immobilized TiO2 powder films for the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in water. Appl Catal B 47:73–84

Banat FA, Al-Bashir B, Al-Ashes S, Hayajnesh O (2000) Adsorption of phenol by bentonite. Environ Pollut 107:391–398

Binas V, Venieri D, Kotzias D, Kiriakidis G (2017) Modified TiO2 based photocatalysts for improved air and health quality. J Mater 3:3–16

Bosc F, Ayral A, Albouy PA, Guizard C (2003) A simple route for low-temperature synthesis of mesoporous and nanocrystalline anatase thin films. Chem Mater 15:2463–2468

Chen X, Mao SS (2007) Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem Rev 107:2891–2959

Chen LC, Tsai FR, Huang CM (2005) Photocatalytic decolorization of methyl orange in aqueous medium of TiO2 and Ag–TiO2 immobilized on γ-Al2O3. J Photochem Photobiol, A 170:7–14

Chin S, Park E, Kim M, Jurng J (2010) Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue with TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by a thermal decomposition process. Powder Technol 201:171–176

Choi H, Stathatos E, Dionysiou DD (2006) Sol–gel preparation of mesoporous photocatalytic TiO2 films and TiO2/Al2O3 composite membranes for environmental applications. Appl Catal B 63:60–67

Dai JY, Chen WP, Pang GKH, Lee PF, Lam HK, Wu WB, Choy CL (2003) Ambient-temperature incorporated hydrogen in Nb: SrTiO3 single crystals. Appl Phys Lett 82:3296–3298

Daneshvar N, Salari D, Niaei A, Khataee AR (2006) Photocatalytic degradation of the herbicide erioglaucine in the presence of nanosized titanium dioxide: comparison and modeling of reaction kinetics. J Environ Sci Health Part B 41:1273–1290

Deguchi T, Imai K, Matsui H, Iwasaki M, Tada H, Ito S (2001) Rapid electroplating of photocatalytically highly active TiO2-Zn nanocomposite films on steel. J Mater Sci 36:4723–4729

Dutta S, Basu JK, Ghar RN (2001) Studies on adsorption of p-nitrophenol on charred saw-dust. Sep Purif Technol 21:227–235

Emam EA (2012) Effect of ozonation combined with heterogeneous catalysts and ultraviolet radiation on recycling of gas-station wastewater. Egypt J Petrol 21:55–60

Ennis CP, Kaiser RI (2010) Mechanistical studies on the electron-induced degradation of polymethylmethacrylate and Kapton. Phys Chem Chem Phys 12:14902–14915

Farkas B, Budai J, Kabalci I, Heszler P, Geretovszky Z (2008) Optical characterization of PLD grown nitrogen-doped TiO2 thin films. Appl Surf Sci 254:3484–3488

Fujimura K, Yoshikado S (2003) Preparation of TiO2 thin film for dye sensitized solar cell deposited by electrophoresis method. In Key Engineering Materials 248:133–136.Trans Tech Publications Ltd.

Gopalakrishnan K, Subrahmanyam KS, Kumar P, Govindaraj A, Rao CNR (2012) Reversible chemical storage of halogens in few-layer graphene. Rsc Adv 2:1605–1608

Grebel JE, Pignatello JJ, Mitch WA (2010) Effect of halide ions and carbonates on organic contaminant degradation by hydroxyl radical-based advanced oxidation processes in saline waters. Environ Sci Technol 44:6822–6828

Gulley-Stahl H, Hogan PA, Schmidt WL, Wall SJ, Buhrlage A, Bullen HA (2010) Surface complexation of catechol to metal oxides: an ATR-FTIR, adsorption, and dissolution study. Environ Sci Technol 44:4116–4121

György E, Socol G, Axente E, Mihailescu IN, Ducu C, Ciuca S (2005) Anatase phase TiO2 thin films obtained by pulsed laser deposition for gas sensing applications. Appl Surf Sci 247:429–433

Hadjiivanov K, Saur O, Lamotte J, Lavalley JC (1994) FT-IR spectroscopic study of NH3 and CO adsorption and coadsorption on TIO2 (anatase). Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 187:281–300

Hishikawa Y, Togawa E, Kondo T (2017) Characterization of individual hydrogen bonds in crystalline regenerated cellulose using resolved polarized FTIR spectra. ACS omega 2:1469–1476

Hu X, Lam FL, Cheung LM, Chan KF, Zhao XS, Lu GQ (2001) Copper/MCM-41 as catalyst for photochemically enhanced oxidation of phenol by hydrogen peroxide. Catal Today 68:129–133

Ibhadon AO, Fitzpatrick P (2013) Heterogeneous photocatalysis: recent advances and applications. Catalysts 3:189–218

Khalifa ZS, Mahmoud SA (2017) Photocatalytic and optical properties of titanium dioxide thin films prepared by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Physica E 91:60–64

Kim DJ, Hahn SH, Oh SH, Kim EJ (2002) Influence of calcination temperature on structural and optical properties of TiO2 thin films prepared by sol–gel dip coating. Mater Lett 57:355–360

Kiwi J, Grätzel M (1987) Light-induced hydrogen formation and photo-uptake of oxygen in colloidal suspensions of α-Fe2O3. J Chem Soc Farad Trans 1 Phys Chem Condensed Phases 83: 1101–1108.

Konstantinou IK, Albanis TA (2004) TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: kinetic and mechanistic investigations: a review. Appl Catal B 49:1–14

Kılıc M, Cınar Z (2008) Hydroxyl radical reactions with 4-chlorophenol as a model for heterogeneous photocatalysis. J Mol Struct (Thoechem) 851:263–270

Li Puma G, Yue PL (2002) Effect of the radiation wavelength on the rate of photocatalytic oxidation of organic pollutants. Ind Eng Chem Res 41:5594–5600

Lin H, Rumaiz AK, Schulz M, Wang D, Rock R, Huang CP, Shah SI (2008) Photocatalytic activity of pulsed laser deposited TiO2 thin films. Mater Sci Eng, B 151:133–139

Lukes P, Clupek M, Sunka P, Peterka F, Sano T, Negishi N, Takeuchi K (2005) Degradation of phenol by underwater pulsed corona discharge in combination with TiO2 photocatalysis. Res Chem Intermed 31:285–294

Mahmoodi NM, Arami M, Limaee NY, Tabrizi NS (2006) Kinetics of heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of reactive dyes in an immobilized TiO2 photocatalytic reactor. J Colloid Interface Sci 295:159–164

Mahmoud S A, Yassitepe E, Shah S I (2013) Photolysis and photocatalysis of 1, 4 dichlorobenzene using sputtered TiO2 thin films. In Materials Science Forum 734: 215–225. Trans Tech Publications Ltd.

Milanović M, Stijepović I, Nikolić LM (2010) Preparation and photocatalytic activity of the layered titanates. Process Appl Ceram 4:69–73

Mohanty K, Jha M, Meikap BC, Biswas MN (2005) Preparation and characterization of activated carbons from Terminalia arjuna nut with zinc chloride activation for the removal of phenol from wastewater. Ind Eng Chem Res 44:4128–4138

Morgado E, de Abreu MA, Moure GT, Marinkovic BA, Jardim PM, Araujo AS (2007) Characterization of nanostructured titanates obtained by alkali treatment of TiO2-anatases with distinct crystal sizes. Chem Mater 19:665–676

Morterra C, Magnacca G (1996) A case study: surface chemistry and surface structure of catalytic aluminas, as studied by vibrational spectroscopy of adsorbed species. Catal Today 27:497–532

Mukherjee D, Barghi S, Ray AK (2014) Preparation and characterization of the TiO2 immobilized polymeric photocatalyst for degradation of aspirin under UV and solar light. Processes 2:12–23

Mukherjee S, Kumar S, Misra AK, Fan M (2007) Removal of phenols from water environment by activated carbon, bagasse ash and wood charcoal. Chem Eng J 129:133–142

Muneer M, Qamar M, Saquib M, Bahnemann DW (2005) Heterogeneous photocatalysed reaction of three selected pesticide derivatives, propham, propachlor and tebuthiuron in aqueous suspensions of titanium dioxide. Chemosphere 61:457–468

Nakamura T, Ichitsubo T, Matsubara E, Muramatsu A, Sato N, Takahashi H (2005) Preferential formation of anatase in laser-ablated titanium dioxide films. Acta Mater 53:323–329

Namane A, Mekarzia A, Benrachedi K, Belhaneche-Bensemra N, Hellal A (2005) Determination of the adsorption capacity of activated carbon made from coffee grounds by chemical activation with ZnCl2 and H3PO4. J Hazard Mater B 119:189–194

Özbelge TA, Özbelge ÖH, Başkaya SZ (2002) Removal of phenolic compounds from rubber–textile wastewaters by physico-chemical methods. Chem Eng Process 41:719–730

Rachel A, Subrahmanyam M, Boule P (2002) Comparison of photocatalytic efficiencies of TiO2 in suspended and immobilized form for the photocatalytic degradation of nitrobenzenesulfonic acids. Appl Catal B 37:301–308

Sato N, Matsuda M, Yoshinaga M, Nakamura T, Sato S, Muramatsu A (2009) the synthesis and photocatalytic properties of nitrogen doped TiO2 films prepared using the AC-PLD method. Top Catal 52:1592–1597

Serpone N, Emeline AV, Horikoshi S, Kuznetsov VN, Ryabchuk VK (2012) On the genesis of heterogeneous photocatalysis: a brief historical perspective in the period 1910 to the mid-1980s. Photochem Photobiol Sci 11:1121–1150

Socol G, Gnatyuk Y, Stefan N, Smirnova N, Djokić V, Sutan C, Mihailescu IN (2010) Photocatalytic activity of pulsed laser deposited TiO2 thin films in N2, O2 and CH4. Thin Solid Films 518:4648–4653

Stathatos E, Lianos P, Tsakiroglou C (2004) Highly efficient nanocrystalline titania films made from organic/inorganic nanocomposite gels. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 75:255–260

Su C, Hong BY, Tseng CM (2004) Sol–gel preparation and photocatalysis of titanium dioxide. Catal Today 96:119–126

Suda Y, Kawasaki H, Ueda T, Ohshima T (2004) Preparation of high quality nitrogen doped TiO2 thin film as a photocatalyst using a pulsed laser deposition method. Thin Solid Films 453:162–166

Suda Y, Kawasaki H, Ueda T, Ohshima T (2005) Preparation of nitrogen-doped titanium oxide thin film using a PLD method as parameters of target material and nitrogen concentration ratio in nitrogen/oxygen gas mixture. Thin Solid Films 475:337–341

Sun H, Bai Y, Liu H, Jin W, Xu N (2009) Photocatalytic decomposition of 4-chlorophenol over an efficient N-doped TiO2 under sunlight irradiation. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem 201:15–22

Tan Y N, Wong C L, Mohamed A R (2011) An Overview on the Photocatalytic Activity of Nano-Doped-TiO2 in the Degradation of Organic Pollutants. International Scholarly Research Notices 2011 Article ID 261219.

Tancredi N, Medero N, Moller F, Piriz J, Plada C, Cordero T (2004) Phenol adsorption onto powdered and granular activated carbon, prepared from Eucalyptus wood. J Colloid Interface Science 279:357–363

Tanthapanichakoon W, Ariyadejwanich P, Japthong P, Nakagawa K, Mukai SR, Tamon H (2005) Adsorption–desorption characteristics of phenol and reactive dyes from aqueous solution on mesoporous activated carbon prepared from waste tires. Water Res 39:1347–1353

Truyen D, Courty M, Alphonse P, Ansart F (2006) Catalytic coatings on stainless steel prepared by sol–gel route. Thin Solid Films 495:257–261

Tsoncheva T, Roggenbuck J, Tiemann M, Ivanova L, Paneva D, Mitov I, Minchev C (2008) Iron oxide nanoparticles supported on mesoporous MgO and CeO2: A comparative physicochemical and catalytic study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 110:339–346

Velo-Gala I, López-Peñalver JJ, Sánchez-Polo M, Rivera-Utrilla J (2013) Activated carbon as photocatalyst of reactions in aqueous phase. Appl Catal B 142:694–704

Wu J, Rudy K, Spark J (2000) Oxidation of aqueous phenol by ozone and peroxidase. Adv Environ Res 4:339–346

Zhang M, Redfern SA, Salje EK, Carpenter MA, Hayward CL (2010) Thermal behavior of vibrational phonons and hydroxyls of muscovite in dehydroxylation: In situ high-temperature infrared spectroscopic investigations. Am Miner 95:1444–1457

Zhao L, Jiang Q, Lian J (2008) Visible-light photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped TiO2 thin film prepared by pulsed laser deposition. Appl Surf Sci 254:4620–4625

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant No. 0809174 DMR- Ceramics, OISE – Cooperative Science Program.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, S.I., Mahmoud, S.A., Bendary, S.H. et al. Efficient removal of 2-chlorophenol from aqueous solution using TiO2 thin films/alumina disc as photocatalyst by pulsed laser deposition. Appl Water Sci 11, 44 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01372-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01372-x