Qunyan Maggie Zhong, Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Howard Norton, Unitec Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Zhong, Q. M., & Norton, H. (2019). Exploring the roles and facilitation strategies of online peer moderators. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(4), 379-400. https://doi.org/10.37237/100405

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

Whilst peer facilitation is deemed to be a beneficial alterative strategy in an asynchronous online discussion, a review of the literature indicates that previous studies have primarily focused on the instructor as the facilitator. Inquiries into the roles that student facilitators perform and strategies they deploy to promote meaningful dialogues and participation in a student-led online discussion board have not been widely explored. Using posted messages of seven student facilitators in a peer-moderated online discussion forum, this study aimed to address the gap in the literature. Content analysis of the data revealed that the student moderators played four major roles during the discussions: 1) a knowledge constructor who actively engaged in a collective inquiry and contributed to a deeper understanding of a subject matter; 2) a team builder who expended considerable efforts to create group cohesion to achieve their learning objectives as a team; 3) a motivator who encouraged and inspired team members to engage in and contribute to the discussion; 4) an organiser who managed and monitored each phase of the discussion and orchestrated the subsequent group oral presentation. The findings suggest that assigning students to lead online discussions is an effective strategy to foster learner autonomy and nurture student leaders. The paper concludes with pedagogical implications and directions for future research.

Keywords: asynchronous online discussion forum; student facilitation strategy; student facilitators; student-moderated discussion

Advances in technologies over the last two decades have generated a paradigm shift in education where educational technologies, e.g. computer-mediated communication (CMC) and Learning Management Systems (LMS), are used increasingly to support and complement educational practices. Initially used predominantly as an approach to distance learning, the asynchronous online discussion forum has now become the most widely adopted platform for exchanging information, communicating and supporting learning in both blended and face-to-face learning (Ghadirian, Salehi & Ayub, 2018; Loncar, Barrett & Liu, 2014; Zhong & Norton, 2018). Referred to as the ‘beating heart’ (Sull, 2009, p.65) of online course activities, asynchronous online discussion forums usually use a text and web-based environment to enable students and instructors to interact asynchronously without boundaries of time and distance. The interactional discussion requires students to read and contribute to various discussion threads by writing posts and responding to the contributions of others. The platform presents discussions chronologically whereby the related answers are displayed attached to each topic, thus forming a discussion tree.

The benefits of asynchronous online discussion boards have been well-documented (Reinders & White, 2016; Zhong & Norton, 2018). The most frequently cited benefit is the collaborative learning condition where knowledge can be co-constructed (De Oliveira & Olesova, 2013; Ghadirian et al., 2018; Zingaro & Oztok, 2012). Additionally, online discussions afford higher-order thinking. The delayed feature in discussion boards provides learners with extra time to reflect on written messages and conduct research before responding, which can result in more in-depth and reasoned responses (Buckley, 2011; Curry & Cook, 2014; Hew & Cheung, 2008; Klisc, McGill & Hobbs, 2012). Furthermore, online discussions can improve students’ social skills, as they enable students to interact with others, e.g. peers, experts or teachers (Cho, 2016; Lu, Yang & Yu, 2013). Finally, unlike traditional classrooms, online discussion creates a more inclusive, non-threatening learning environment which encourages learner participation, particularly the quiet ones who may not participate in traditional classroom discussions (Dzubinski, 2014; Zhong, 2013).

Notwithstanding the affordances offered by asynchronous online discussion boards, their realization hinges on effective facilitation. A review of the literature indicates that while a number of studies have focused on how facilitators moderate discussions (Curry & Cook, 2014; Demman, Phirangee & Hewitt, 2017; Salmon, 2000, 2011), they mostly focus on instructors as moderators. Hence the strategies that student moderators employ to facilitate discussion boards are not well understood, especially in the field of second language acquisition where little research has been conducted in this area. This study attempts to address this gap in the literature, seeking to provide insights into the different roles that second language (L2) student moderators performed and the strategies they employed in an online discussion. It is hoped that the closer examination will further our understanding of the facilitating process, particularly in discussions led by L2 learners. This knowledge can be used to inform prospective course design and student facilitators’ training. The ultimate goal is to help implement the use of educational technologies more effectively in the classroom and achieve successful learning outcomes.

Research into Peer-moderated Asynchronous Online Discussions

Traditionally, teachers serve as facilitators in online discussion forums. However, major drawbacks of teacher-facilitated discussions are related to the high demand of time commitment on the teacher’s part, teacher-centred discussions and authoritarian presence (Clarke & Bartholomew, 2014; Correia & Barran, 2010; Hew, 2015; Rourke & Anderson, 2002). Current educational practices embrace learner-centred approaches whereby greater emphasis is placed on learners taking charge of their own learning. In alignment with this paradigm shift, facilitation in online discussions is perceived as a shared responsibility between teachers and students; hence assigning students as moderators to lead group activities has become a wide-spread alternative in educational sectors (Demmans, Phirangee & Hewitt, 2017; Phirangee, Epp & Hewitt, 2016; Xie, Yu, & Bradshaw, 2014; Zhong & Norton, 2018). In peer moderation, the instructing teacher performs a minimal facilitative role while students are at the forefront, leading the discussion.

A review of the literature indicates that existing research into peer-moderated online discussions has predominantly focused on the effects of peer facilitation on learning. In an early investigation of 16 pre-service teachers, Baran and Correia (2009) found that peer facilitation motivated participants to interact actively in the discussions and provided an atmosphere for involvement and commitment. In another study, Xie et al. (2014) revealed that peer facilitators changed contributions to online forum discussion significantly in terms of quantity and quality. Similar results were yielded in Hew’s (2015) case study, reporting students’ preference for peer facilitation were predominantly associated with greater freedom in voicing their own views and greater ownership in determining the direction of the discussion. Apart from the positive effect on students’ engagement and participation, peer moderation is also reported as having a positive impact on students’ meta-cognitive knowledge and self-regulation skills. Drawing on the Community of Inquiry (COI) framework (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007), Snyder and Drignus (2014) revealed the development of dimensions of metacognition in the student-led discussion, concluding that student facilitation could be used as a useful and effective strategy with instruction and guidance.

Furthermore, peer facilitation has been found to be positively correlated with students’ higher-order cognition. Framing their study through the lens of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning domains, Zha and Ottendorfer (2011) focused on the effect of peer moderation on assigned student moderators’ cognitive achievement. The results revealed that lower-order cognitions were achieved in all students while peer moderators outperformed their peers in higher-order thinking. In their study, Belcher, Hall, Kelley and Pressey (2015) found significant correlations between critical thinking and student interactions. This was accounted for by the fact that when the students recognised that the instructor was less engaged, they may consciously or unconsciously increase their cognitive engagement with peers. Drawing on the same framework, Ghadirian et al. (2018) compared knowledge dimensions and cognitive processes of two discussion groups, high- and low-quality, in peer-moderated online discussions, revealing that both groups exhibited the frequent use of metacognitive knowledge and cognitive process of understanding.

Another line of research into student-facilitated online discussions is process-oriented. Whilst Salmon (2000, 2011) points out that effective facilitation is a pivotal component for the success of online discussions, a handful of studies focus on detecting strategies that peer moderators adopt during the process of discussion. In their case study, Baran and Correia (2009) categorised the strategies used by student facilitators into three types: inspirational facilitation strategy, whereby the student facilitator invited their peers to imagine idealistic teaching and learning scenarios and discuss ways to achieve them; practice-oriented facilitation strategy, whereby participants were encouraged to reflect on real-life teaching and learning contexts; highly structured facilitation strategy, whereby a structure was used to engage peers and guide the conversations. These strategies were found to assist student facilitators to promote active participation and meaningful dialogue among peers. In their correlation study of 738 posting messages, Chen, Lei and Cheng (2019) detected several facilitation techniques including questioning, making clarification, promoting connections, summarising, providing information and using positive social cues. The last three facilitation techniques (summarising, providing information and using positive social cues) were found to significantly correlate with higher-level thinking. Drawing on Salmon’s (2000) framework, De Smet, Van Keer, and Valcke (2009) found three different tutor styles within an online cross-age peer tutoring context: motivators that praised others for their contribution; informers that gave more information exchange support and knowledge constructors who supplied high levels of knowledge construction support. Utilising the same framework, Ghadirian and Ayub (2017) identified three patterns of moderating behaviour: high-, mid- and low-level moderators. High-level moderators distinguished themselves by providing knowledge construction support and showing high levels of online participation. In comparison, mid-level moderators dominated information support, and socialization was the main behavioural feature of low-level moderators.

Despite the potential of student-led online discussions, the literature review indicates that previous research studies largely investigate the effects of peer-moderated discussion. In comparison, process-oriented studies aiming to understand student moderators’ facilitating behaviours in peer-facilitation contexts remain rather limited and outdated (predominantly conducted in the late 2000s). Additionally, the majority of previous investigations have been undertaken in other disciplines where participating students were typically native speakers of the target language. An understanding of how L2 student-facilitators lead online discussions and how their role is manifested during the process of task negotiation and completion have been barely explored. Further investigations are warranted, focusing on peer facilitation, particularly the techniques L2 student facilitators employ. In terms of research methods, prior studies have been predominantly quantitative using cluster analysis to detect patterns of facilitation. Qualitative investigations grounded in the data are lacking. This study attempts to address these gaps in the literature, focusing on different roles that L2 student facilitators assumed during the discussions and strategies they employed to perform these roles. It is hoped that the findings will shed further light on the phenomenon. Specifically, the current study aims to address these research questions:

- What roles do the student facilitators perform in a student-led online discussion forum?

- What strategies do the student facilitators employ to accomplish these roles?

Current Study

The research context and participants

Although the research inquiry was situated at a university in China, the course that forms the basis of this research study was a New Zealand business qualification. Part of a joint business degree programme agreement between a New Zealand and a Chinese tertiary institution required the New Zealand institution to deliver a series of intensive, credit-bearing courses on site at the host (Chinese) institution. The course under this study focused on English for Academic Purposes (EAP) taught to second-year university students pursuing a Bachelor of Accountancy. Due to the intensive nature of onsite delivery (five weeks), a blended learning strategy was adopted in the course design, combining predominantly face-to-face teaching complemented by two online components. Part A consisted of a series of quizzes covering the course content, academic skills and vocabulary. Part B involved an online forum discussion using the forum function on Moodle, the LMS adopted by the institution. This inquiry focused exclusively on the latter.

The forum discussion task required students to work in small groups (four to five students), defining corporate social responsibility (CSR) and providing examples of good and bad CSR practices in the corporate world. The task completion entailed (i) posting at least three messages of 80 words each (a minimum of 240 words) demonstrating understanding of the task topic, (ii) posting three questions to team members and (iii) sharing three relevant resource links with the team. The forum discussion was worth 7% of the overall course assessment and students were marked on the quality and quantity of their contributions. An additional 15% of the course assessments were allocated to a subsequent collaborative oral presentation based on the online discussion. The forum was student-facilitated whereby a randomly assigned peer moderator (the first student from alphabetical class lists in every group of five) led the discussion and the instructors remained observers, i.e. teachers were not directly involved in the discussion. However, a model of a forum discussion on a different topic was provided on the Moodle site and the students were directed to study it in their own time prior to commencing their discussion.

The purpose of the task design was two-fold. First, it aimed to increase levels of interaction among students and to assist them to co-construct the content knowledge, leading to the creation of a high-quality group oral presentation. Second, it was hoped that the student-led forum would ease the high demand on teachers’ commitment and provide a framework for free and fluent writing, unconstrained by a teacher’s presence (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003).

As both researchers taught on the course, in order to avoid conflicts of interest, they contacted potential participating students six months after they had completed the course and their grades had been approved. An invitation email with attached information sheets explaining the anonymous, confidential and voluntary nature of this study was sent to all the potential participants (n=103). Having received full information of the study, 20 students, of whom seven students were moderators, gave permission to access their archived discussion forum threads. The low response rate may be attributed to the geographical distance and time lapse between the study and their course completion.

Data collection and analysis

This inquiry was part of a larger project investigating affordances of online discussion forums for language learners (Zhong & Norton, 2018). The focus of this report was on the strategies that the student facilitators employed during the forum discussion. To this end, we utilised 59 archived messages (approx. 6,880 words) posted by seven student moderators over a period of two weeks.

Content analysis (Sandelowski, 2000; Smith, 2000) was employed to analyse the data collected. Because of the exploratory nature of this research, the framework of grounded approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was drawn upon to analyse the posted messages, i.e. there was no pre-conceived framework or a priori code. The indicators of student facilitation strategies surfaced inductively from the data and were continually refined through our interaction with the data. Specifically, data analysis involves four phases:

Phase 1: previewing. In this phase, we read and re-read the online posted messages independently while making notes and memos in the margins that reflected our thinking.

Phase 2: open coding. This phase started with open coding the set of data of the first student facilitator. During the line-by-line scrutiny of the data, codes were affixed to the units of analysis. Following Ghadirian and Ayub (2017), we used a unit of meaning in a message as the unit of analysis owing to the multidimensional activity of moderating and the fact that a single posted message may display several strategies or roles that a student moderator performed. The unit of meaning could be words, phrases, complete sentences, utterances or extended discourse. Each unit was identified by the participating students and provisional themes.

Phase 3: categorising. This phase involved data reduction where similar themes were grouped into tentative categories. Propositional statements were made for each of these categories. For example, we subsumed the six strategies, creating an inspiring team name; using positive and bonding language; acknowledging team contributions; self-introduction, apologising and establishing team goals, under one category, and the proposition we created was ‘team builders’.

Phase 4: consolidating categories. In this phase, all the categories were tested against the set of data of the subsequent participants, to see if the tentative categories existed and continued to hold. If new tentative categories were identified, we would re-examine the previous cases and add the new provisional categories to the subsequent data analysis.

It was a process of recursive analysis where data were read repeatedly; new codes were added until saturation was reached, i.e., no new themes and categories were found, and salient themes, categories or recurring patterns began to emerge. In order to capture both patterns and examples, this report will balance the summary and quotation (Morgan, 1988) and the quotes are used intact (pseudonyms, however, used for anonymity and confidentiality) directly from the discussion postings with the original grammar and language retained.

Results and Discussion

In compliance with the process of data analysis described above, 4 roles and 16 strategies emerged from the data. Table 1 summarises these roles with their operational definitions along with the strategies deployed by the student moderators to perform these roles.

Table 1

Roles and Facilitation Strategies Deployed by Student Facilitators

Knowledge constructors

Knowledge constructors

A prominent theme emerging from the data was that the student moderators played a role as knowledge constructors whereby they actively contributed to the process of collaborative inquiry leading to a deeper understanding of the concept under discussion, CSR. Table 2 gives a breakdown of the three strategies employed by the student moderators to perform the role.

Table 2

Strategies and their Frequency for Knowledge Construction

The most widely used strategy by all the student moderators to advance the understanding of the topic was to respond to queries from their team members. While students in East Asian contexts are usually reported to be reluctant to give opinions in the face-to-face classroom (Zhong, 2013), the student moderators were, in the main, not shy from articulating their perspectives using often quite direct language. To illustrate this, a team member questioned the necessity of CSR. In her view, the concept was fuzzy and against the purpose of the establishment of a corporation, the ultimate goal of which was to make a profit. Student moderator 7 seemed to hold a different view to this proposition:

The most widely used strategy by all the student moderators to advance the understanding of the topic was to respond to queries from their team members. While students in East Asian contexts are usually reported to be reluctant to give opinions in the face-to-face classroom (Zhong, 2013), the student moderators were, in the main, not shy from articulating their perspectives using often quite direct language. To illustrate this, a team member questioned the necessity of CSR. In her view, the concept was fuzzy and against the purpose of the establishment of a corporation, the ultimate goal of which was to make a profit. Student moderator 7 seemed to hold a different view to this proposition:

I don’t think so. In my opinion, the purpose of enterprises existence is not just to make a profit and the company needs to perform social responsibility. I think that corporate social responsibility for the continuing operations of an enterprise is very necessary, although corporate social responsibility must be established on the basis of the company’s long-term development goals. So only we associate the social responsibility with the interests of all parties, can companies carry out social responsibility and have realistic foundation and possibility.

In addition to expressing their views arising from team members’ queries, the student moderators also posted self-initiated messages to contribute to the collaborative process of knowledge construction. One outcome of this collaborative inquiry was the formation of a different or alternative perspective of examining the concept. Another outcome of the enhanced understanding was that students were engaged in critical thinking by assessing their own cultural context. When confronted with a question relating to the absence and unawareness of CSR in China, a student moderator blamed enterprises and factories who “have been causing so much pollution by producing more production or doing more works so that they can do more transactions to get more money. For making money, they are selfish to care about their benefit” (Participant 5). In another group, a student facilitator was not afraid to hold the government accountable: “first of all, the government should deliver more policies about CSR because the attitude of government is one of the main drives of the Chinese CSR growth as many companies pay more attention about government’s policies in China…” (Participant 4)

This co-constructive process appeared to enhance learners’ understanding of the subject content and developed a shared repertoire of resources. Evidence also revealed that students were very appreciative of their enhanced understanding as a result:

Communicating is a great skill for us to enhance understanding. When we share opinions, it is possible for us to get new ideas from each other. On the other hand, there is no doubt that discussing improves working efficiency in a great degree instead of being buried in piles of resources along. (Participant 2)

Team builders

Another noticeable theme that emerged from the data was that the seven student moderators functioned as team builders. They posted a considerable number of messages to establish the cohesion within their group to create a community of learning, particularly at the initial stage of the forum discussion. Table 3 summarises the six types of strategies they employed to perform the role.

Table 3

Strategies and Their Frequency for Team Building

It is evident that the use of inclusive language is the most prevalent and frequent strategy used by the student moderators. Specifically, they used an overwhelming number of different forms of collective pronouns to address the team, e.g., “we”, “us”, “our” (frequency = 73). Language can indicate whether members of a group see themselves as individuals within the collective or conversely identify themselves as a single unit (a group), with a collective sense of purpose. The use of bonding language in a post may create a feeling in the group that they were collectively part of something special and collective and they should strive to achieve well as a group. To this end, the moderators used two additional strategies. One was to set up team goals: “we will communicate with each other online to share new ideas, leading to create a fantastic group presentation” (Participant 2) and the other was to create a team slogan, “our team slogan is Making amazing miracles forever” (Participant 3). This slogan, or mission statement, suggests that the student moderator is enthusiastic, an idealist who wanted the group to believe they could achieve anything as a team. A unified sense of purpose, or at the very least the aim of buying into this collective goal was clearly articulated.

It is evident that the use of inclusive language is the most prevalent and frequent strategy used by the student moderators. Specifically, they used an overwhelming number of different forms of collective pronouns to address the team, e.g., “we”, “us”, “our” (frequency = 73). Language can indicate whether members of a group see themselves as individuals within the collective or conversely identify themselves as a single unit (a group), with a collective sense of purpose. The use of bonding language in a post may create a feeling in the group that they were collectively part of something special and collective and they should strive to achieve well as a group. To this end, the moderators used two additional strategies. One was to set up team goals: “we will communicate with each other online to share new ideas, leading to create a fantastic group presentation” (Participant 2) and the other was to create a team slogan, “our team slogan is Making amazing miracles forever” (Participant 3). This slogan, or mission statement, suggests that the student moderator is enthusiastic, an idealist who wanted the group to believe they could achieve anything as a team. A unified sense of purpose, or at the very least the aim of buying into this collective goal was clearly articulated.

Other strategies that student moderators adopted to strengthen group affiliation include self-introduction where moderators introduced themselves to the team members and addressed their team members by their name. Due to large class sizes and a predominantly teacher-centred teaching style in their Chinese classes, many students did not know each other. By introducing themselves in the initial posting, student moderators initiated an icebreaker process online. Some of the student moderators also introduced the entire group, thereby emphasising the collective right from the outset. Additionally, when a team member posted a message, the student moderators expressed their appreciation and if they were late with their responses, they apologised to the team: “I am so sorry about the abcense of me at yesterday. But I had already read your words, I just can not to reply yesterday” (Participant 6). This posting suggests the student moderator felt anxious about abandoning their post and the comment demonstrates the responsibility they imposed upon themselves to contribute and to be visible as the team leader. The sense of responsibility to the collective is evident. A combination of these strategies helped to develop a cohesive group where each member felt appreciated and valued and they were willing to achieve well as a team: “I enjoy cooperating with you very much and I understand the meaning of cooperation deeply, which is an invaluable wealth for me in the long run” (Participant 2).

Motivators

The third role surfaced from the data was a motivator where the student moderators encouraged their team members to participate in and contribute to the forum discussion. Two strategies were identified (See table 4).

Table 4

Strategies and Their Frequency for Motivation

Table 4 reveals the predominant motivating strategy involved inviting and eliciting views from team members, especially by asking questions, “Do you think win-win could be a CSR?” “Can we get something good from it when we do CSR?” “I’d like you to provide me with more examples of bad CSR practices”. Direct questions and indirect questions functioned effectively as a means to ensuring that team members were engaged in the conversation and contributed to the discussion threads until every aspect of the discussion topic was covered. Another strategy was related to the use of encouraging and praising language, e.g. “How valuable the question is you have asked”; “Continue refuelling!”; “you all have done pretty well”; “I’m looking forward to your fluent speech on next Tuesday”; “she could achieve a perfect conclusion”. Although many factors may have contributed to students’ participation, the use of motivating strategies used by the student moderators seemed to play a critical role in inspiring the team members and encouraging them to contribute to the team discussion, eventually leading to the task completion.

Table 4 reveals the predominant motivating strategy involved inviting and eliciting views from team members, especially by asking questions, “Do you think win-win could be a CSR?” “Can we get something good from it when we do CSR?” “I’d like you to provide me with more examples of bad CSR practices”. Direct questions and indirect questions functioned effectively as a means to ensuring that team members were engaged in the conversation and contributed to the discussion threads until every aspect of the discussion topic was covered. Another strategy was related to the use of encouraging and praising language, e.g. “How valuable the question is you have asked”; “Continue refuelling!”; “you all have done pretty well”; “I’m looking forward to your fluent speech on next Tuesday”; “she could achieve a perfect conclusion”. Although many factors may have contributed to students’ participation, the use of motivating strategies used by the student moderators seemed to play a critical role in inspiring the team members and encouraging them to contribute to the team discussion, eventually leading to the task completion.

Organisers

The last theme emerged from the data was that the student moderators played an active role as organisers for the forum discussion as well as the subsequent group oral presentation. This organisational role was essential at different phases of the forum discussion.

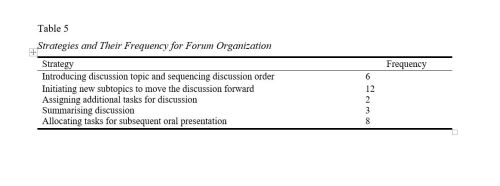

Table 5

Strategies and Their Frequency for Forum Organization

Table 5 illustrates five strategies that the student moderators adopted to perform this role. At the outset of the discussion, all the student moderators introduced the discussion topic and sequenced the discussion order. This strategy was vital as it ensured that the team members were clear about the topic and process of conducting the discussion. During the discussion, the student moderators deployed three strategies to progress it. One of the strategies was to initiate a new topic when the previous topic had been discussed extensively and exhaustively. When a topic was not discussed substantively, some student moderators asked the team to do additional reading on the topic. The data also revealed that two student moderators summarised the previous discussion before progressing to the next phase of the discussion. When the forum discussion ended, two student moderators assumed an additional role as a group oral presentation organiser. They coordinated tasks for developing power point slides and organized time for group practice:

Table 5 illustrates five strategies that the student moderators adopted to perform this role. At the outset of the discussion, all the student moderators introduced the discussion topic and sequenced the discussion order. This strategy was vital as it ensured that the team members were clear about the topic and process of conducting the discussion. During the discussion, the student moderators deployed three strategies to progress it. One of the strategies was to initiate a new topic when the previous topic had been discussed extensively and exhaustively. When a topic was not discussed substantively, some student moderators asked the team to do additional reading on the topic. The data also revealed that two student moderators summarised the previous discussion before progressing to the next phase of the discussion. When the forum discussion ended, two student moderators assumed an additional role as a group oral presentation organiser. They coordinated tasks for developing power point slides and organized time for group practice:

Yesterday we haven’t got the chance to practice our PPT in class due to limited time. However, we still need to spare some time practicing and modifying our PPT. Could you please send me your reference links as soon as possible? Could you send your contents to Jianhua at the same time as she will reference them to introduce us? (Participant 2)

Discussion

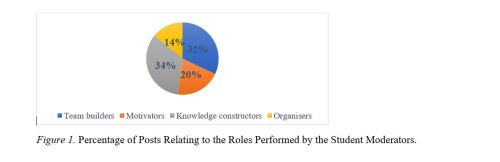

The current study aimed at gaining insight into different roles that L2 student facilitators performed and strategies they deployed during an asynchronous online discussion. Threaded messages revealed that during the two-week online discussion period, student moderators posted a total of 59 messages, of which 182 units were recognised as meaningful units for analysis. Within the 182 units, 61 units were categorised as knowledge constructors and 59 as team builders. The remainders were coded as motivators (=37 units) and organisers (=25 units) respectively (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of Posts Relating to the Roles Performed by the Student Moderators.

Figure 1. Percentage of Posts Relating to the Roles Performed by the Student Moderators.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the most prominent role that the student moderators performed was knowledge construction. 34% of the postings were related to the resources and examples which they used to endorse their own arguments and/or advance the understanding of the topic under discussion, CSR practices in the corporate world. The finding is not surprising and consistent with other findings in the literature (Cho, 2016; De Oliveira & Olesova, 2013; Klisc, McGill & Hobbs, 2012; Lai, 2015). As mentioned in the preceding section, the course entailed students posting three messages and sharing two resources. Like the rest of the team, the student moderators were obligated to meet the requirement. However, the student moderators exceeded the course requirements by a significant margin. Figures 2 and 3 compare the number of postings and the number of word contributions of each student facilitator with those of the course requirements. Their active engagement and contributions to the collaborative knowledge construction are exceptional. This may be accounted for by the leadership role they were assuming, which may have liberated them to act like a leader, i.e. expressing their views more directly and freely. The example they set for the rest of the team may have also inspired their team members, leading to the task completion.

Figure 2. A Comparison of the Number of Posts between Each Participant and the Course Requirement.

Figure 2. A Comparison of the Number of Posts between Each Participant and the Course Requirement.

Figure 3. A Comparison of Word Contributions between Each Participant and the Course Requirement

Figure 3. A Comparison of Word Contributions between Each Participant and the Course Requirement

Another equally noticeable role they performed was team building (32%). The data indicates that the student moderators combined six strategies, using inclusive language in particular, to build a supportive community of learning (Wenger, 1998). Social capital in media-based human interaction has received increasing attention among scholars. Curry and Cook (2014) reported the creation of a wider community of learning bonded learners on a different level. Likewise, Chang and Chuang (2011) confirmed that social interaction and trust had positive effects on the quality of shared knowledge. Although findings of social engagement and group affiliation in online environment are inconclusive (Çelik, 2013; Demmans Epp, Phirangee & Hewitt, 2017; Gilliland, Oyama & Stacey, 2018; Xie, Lu, Cheng, & Izmirli, 2017), the positive, group cohesion was evident in this study. These results could be interpreted in a number of ways. On the one hand, the responsibility for facilitating the group discussion may have given the student moderators a stronger sense of the collective. It could also be argued that the designated role as a student facilitator thrust these student moderators to the apex of the group, which compelled them to be responsible for creating a sense of unity. In other words, they saw their role as de facto leader and team-building was very much part of what a leader should do. The rapport they established among team members appeared to encourage learners to be mutually engaged in the joint project. This finding lent empirical evidence to the proposition that establishing a learning community where learners are socially and emotionally committed is a prerequisite to engage learners in cognitive tasks (Lu et al., 2013; Saqr, Fors, Tedre & Nouri, 2018).

Other roles the student moderators performed included motivators and organisers with 20% and 14% respectively. Through performing these roles, coupled with the use of a variety of strategies, the student moderators ensured the engagement of discussion from their team members, leading to the successful completion of the task. As indicated in the preceding section, these student facilitators were not trained but were randomly assigned to take responsibility due to time constraints. Notwithstanding the uncertainty the task design may have incurred, the data revealed that all the student moderators exhibited leadership qualities. These findings suggest that leadership position, such as those created for this task, could engender expectations among the moderators that they would have to put more effort and work into the situation.

Conclusion, Pedagogical Implications and Limitations

The objective of this study was to discern the predominant role that the student facilitators assumed and to identify the strategies they employed to perform these roles during the process of leading an online discussion forum. Four roles (knowledge constructors, team builders, motivators and organisers) coupled with sixteen strategies emerged from the data. Consistent with previous studies (De Backer, Van Keer, & Valcke, 2012; Ghadirian & Ayub, 2017; Hew, 2015; Snyder & Dringus, 2014; Xie et al., 2014; Zha & Ottendorfer, 2011), this study lent further evidence to the argument that student-led online discussions can be a viable and effective alternative even for L2 learners. The allocation of facilitating roles can empower learners, particularly those learners who lack the confidence and/or skills to lead. The study emphasises the need for every student to be given opportunities to take a leadership role in a discussion activity.

The results of this study have pedagogical implications, particularly for educators who are interested in using student facilitators. First, it is essential to consider how a student facilitator is assigned when designing a course. The student facilitators in this study were randomly selected. Other possibilities include assigning reciprocal roles or rotating the role of facilitators where every student has the opportunity to be a facilitator and a participant, which may promote positive interdependence (Saqr et al., 2018). Additionally, it may be worthwhile to train student facilitators, considering facilitators are instrumental in shaping or influencing the direction of the discourse of an online discussion forum. The training can take different forms. A checklist or a guideline, for example, could be provided, outlining responsibilities at each phase of a forum discussion. Alternatively, a trial facilitating session could be arranged prior to the commencement of forum discussions.

The present study has several limitations, warranting further research. First, due to the low response rate from the students involved, the small and convenience samples limit its representation and wider application. Future studies should examine a larger sample size in different educational contexts. In addition, as the student moderators in this study were randomly assigned and without providing any prior training, an experimental study is warranted to compare strategies employed by student moderators who have received training with those who have not. The findings would provide a useful reference to course designers. Furthermore, this study utilised archived posted messages exclusively to identify their facilitation strategies. Further research may use triangulation in data collection combining posted messages with reflective logs and/or interviews with student facilitators coupled with perceptions of participating students about their preferred facilitation strategies. Finally, the scope of this study was limited to facilitation strategies used by student facilitators. Future research could extend the scope to investigating the relationship between facilitation strategies, and other factors of learning, e.g., knowledge construction, the higher level of thinking, social networks, motivation, quality of postings, and so on.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and helpful suggestions.

Notes on the Contributors

Dr. Qunyan (Maggie) Zhong led this research project and wrote the entire article. She is a senior lecturer in the Department of Language Studies, Unitec Institute of Technology, New Zealand. She holds a PhD and an MA (honours) in Applied Linguistics. Her research interests include individual differences in second language acquisition, learner autonomy and second language classroom research.

Howard Norton was involved in data collection, data analysis, drafting results section and proof reading. He is a senior lecturer in the Department of Language Studies, Unitec Institute of Technology, New Zealand. He holds a Graduate Diploma in Language Teaching, a Post Graduate Diploma in Education (eEducation) and a Master’s in Education. He has a special interest in the pedagogical impacts of technology in the classroom.

References

Barran, E., & Correia, A. P. (2009). Student-led facilitation strategies in online discussion. Distance Education, 30(3), 339-361. doi:10.1080/01587910903236510

Belcher, A., Hall, B., Kelley, K., & Pressey, K. (2015). An analysis of faculty promotion of critical thinking and peer interaction within threaded discussions. Online Learning, 19(4), 37–44. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v19i4.544

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (2003). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (4th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Buckley, F. (2011). Online discussion forums. European Political Science, 10(3), 402-415. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10-1057/eps.2010.76

Çelik, S. (2013). Unspoken social dynamics in an online discussion group: the disconnect between attitudes and overt behaviour of English language teaching graduate students. Education Technology Research Development, 61(4), 665–683. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11423-013-9288-3

Chang, H. H & Chuang, S. (2011). Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management 48(1), 9-18. doi:10.1016/j.im.2010.11.001

Chen, Y., Lei, J., & Cheng, J. (2019). What if online students take on the responsibility: students’ cognitive presence and peer facilitation techniques. Online Learning, 23(1), 37-61. doi:10.24059/olj.v23i1.1348

Cho, H. (2016). Under co-construction: An online community of practice for bilingual pre-service teachers. Computers & Education, 92, 76-89. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.008

Correia, A. P., & Baran, E. (2010). Lessons learned on facilitating asynchronous discussions for online learning. Educacao, Formacao & Tecnologias, 3(1), 59–67. Retrieved from https://eft.educom.pt/index.php/eft/article/view/141

Clarke, L. W., & Bartholomew, A. (2014). Digging beneath the surface: Analyzing the complexity of instructors’ participation in asynchronous discussion. Online Learning, 18(3). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v18i3.414

Curry, J. H., & Cook, J. (2014). Facilitating online discussions at a manic pace: A new strategy for an old problem. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 15(3), 1-11. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 01587919.2013.775715

De Backer, L., Van Keer, H., & Valcke, M. (2012). Exploring the potential impact of reciprocal peer tutoring on higher education students’ metacognitive knowledge and regulation. Instructional Science, 40(3), 559–588. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9190-5

De Oliveira, L., & Olesova, L. (2013). Learning about the literacy development of English language learners in asynchronous online discussions. Journal of Education, 193(2), 15-23. doi:10.1177/002205741319300203

De Smet, M., Van Keer, H., & Valcke, M. (2009). Cross-age peer tutors in asynchronous discussion groups: A study of the evolution in tutor support. Instructional Science, 37(1), 87-105. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9037-2

Demmans Epp, C., Phirangee, K. & Hewitt, J. (2017). Student actions and community in online courses: The roles played by course length and facilitation method. Online Learning, 21(4), 53-77. Retrieved from https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/article/view/1269

Dzubinski, L. (2014). Teaching presence: Co-creating a multi-national online learning community in an asynchronous classroom. Online Learning, 18(2), 1–16. Retrieved from https://olj.onlinelearningconsortium.org/index.php/olj/article/view/412

Hew, K. F. (2015). Student perceptions of peer versus instructor facilitation of asynchronous online discussions: Further findings from three cases. Instructional Science, 43(1), 19–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9329-2

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. The Internet and Higher Education, 10, 157-172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.04.001

Ghadirian, H., & Ayub, A. F. M. (2017). Peer moderation of asynchronous online discussions: An exploratory study of peer e-moderating behaviour. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(1), 1-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2882

Ghadirian, H., Salehi, K., & Ayub, A. F. M. (2018). Exploring the behavioural patterns of knowledge dimensions and cognitive processes in peer-moderated asynchronous online discussions. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 33(1), 1-28. Retrieved from http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/1030/1692

Gilliland, B., Oyama, A. & Stacey, P. (2018). Second language writing in a Mooc: Affordances and missed opportunities. TESL-EJ, 22(1). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume22/ej85/ej85a3/

Klisc, C., McGill, T., & Hobbs, V. (2012). The effect of instructor information provision on critical thinking in students using asynchronous online discussion. International Journal on E-Learning, 11(3), 247-266. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/34568/

Lai, K. (2015). Knowledge construction in online learning communities: a case study of a doctoral course. Studies in Higher Education, 40(4), 561–579. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.831402

Loncar, M., Barrett, N. E., & Liu, G. (2014). Towards the refinement of forum and asynchronous online discussion in educational contexts worldwide: Trends and investigative approaches within a dominant research paradigm. Computers & Education, 73, 93-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.12.007

Lu, J., Yang, J., & Yu, C. (2013). Is social capital effective for online learning? Information & Management, 50, 507-522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.07.009

Morgan, D. L. (1988). Qualitative research methods, Vol. 16. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Norton, H. (2014). Digital storytelling in an L2 context, and its impact on student communication, engagement, and motivation. Master of Education (unpublished Master thesis), The University of Waikato.

Phirangee, K., Epp, C. D., & Hewitt, J. (2016). Exploring the relationships between facilitation methods, students’ sense of community, and their online behaviours. Online Learning Journal [OLJ], 20(2), 134-155. doi:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v20i2.775

Reinders, H., & White, C. (2016). 20 years of autonomy and technology: How far have we come and where to next? Language Learning & Technology, 20(2), 143–154. Retrieved from https://www.lltjournal.org/item/2950

Rourke, L., & Anderson, T. (2002). Using peer teams to lead online discussions. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(1), 1-21. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/2002-1

Salmon, G. (2000). A model for CMC in education and training. E-moderating. The key to teaching and learning online. London, UK: Kogan Page.

Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to online teaching and learning (3rd ed). New York: Routledge.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23, 334-340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4%3C334::aid-nur9%3E3.0.co;2-g

Saqr, M., Fors, U., Tedre, M., & Nouri, J. (2018). How social network analysis can be used to monitor online collaborative learning and guide an informed intervention. PloS One, 13(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194777

Smith, C. P. (2000). Content analysis and narrative analysis. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 313-335). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snyder, M. M., & Dringus, L. P. (2014). An exploration of metacognition in asynchronous student-led discussions: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 18(2), 29-47. doi:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v18i2.418

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Sull, E. C. (2009). The (Almost) complete guide to effectively managing threaded discussions. Distance Learning, 6(4), 65-70. Retrieved from https://www.infoagepub.com/dl-issue.html?i=p54c11772f1a0e

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Xie, K., & Ke, F. (2011). The role of students’ motivation in peer-moderated asynchronous online discussions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 916-930. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010. 01140.x

Xie, K., Yu, C., & Bradshaw, A. C. (2014). Impacts of role assignment and participation in asynchronous discussions in college-level online classes. The Internet and Higher Education, 20, 10-19. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.09.003

Xie, K., Lu, L., Cheng, S., & Izmirli, S. (2017). The interactions between facilitator identity, conflictual presence, and social presence in peer-moderated online collaborative learning. Distance Education, 38(2), 230-244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1322458

Zha, S., & Ottendorfer, C. L. (2011). Effects of peer-led online asynchronous discussion on undergraduate students’ cognitive achievement. The American Journal of Distance Education, 25(4), 238-253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2011.618314

Zhong, Q. (2013). Understanding Chinese learners’ willingness to communicate in a New Zealand ESL classroom: A multiple case study drawing on the theory of planned behaviour. System. 41(3): 740-751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.08.001

Zhong, Q., & Norton, H. (2018). Educational affordances of an asynchronous online discussion forum for language learners. TESL-EJ, 22(3). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume22/ej87/ej87a1/

Zingaro, D., & Oztok, M. (2012). Interaction in an asynchronous online course: A synthesis of quantitative predictors. Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(4), 71-82. doi:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v16i4.265