Abstract

The drilling-related geomechanics requires a better understanding of the encountered formation properties such as poroelastic parameters. This paper shows set of laboratory results of the dynamic Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and Biot’s coefficient for dry and water-saturated Istebna sandstone samples under a series of confining pressure conditions at two different temperatures. The predicted results from Wyllie’s equation were compared to the measured ones in order to show the effect of saturation on the rock weakening. A negative correlation has been identified between Poisson’s ratio, Biot’s coefficient and confining pressure, while a positive correlation between confining pressure and Young’s modulus. The predicted dynamic poroelastic rock properties using the P-wave value from Wyllie’s equation are different from measured ones. It shows the important influence of water saturation on rock strength, which is confirmed by unconfined compressive strength measurement. Linear equations have been fitted for the laboratory data and are useful for the analysis of coupled stress and pore pressure effects in geomechanical problems. Such results are useful for many drilling applications especially in evaluation of such cases as wellbore instability and many other drilling problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The drilling-related geomechanics requires a better understanding of the encountered formation’s properties such as poroelastic parameters because it allows researcher to address numerous technical challenges in petroleum industry. The relationship between applied stresses, pore pressures and strains has been investigated by many researchers in geomechanics discipline (Franquet and Abass 1999; Li et al. 2019; Messori et al. 2019). For example, the mechanical models of rock properties using acoustic properties and the poroelasticity have a significant role in rock mechanics applications, especially in petroleum engineering, including reservoir engineering, directional drilling of wellbore (Knez 2014), production, stimulation process such as hydraulic fracturing (King 1983; Ahmed et al. 2016) and proppant selection (Knez and Calicki 2018; Knez et al. 2019). Thus, solutions of technical issues related to exploration cannot be achieved without understanding the formation rock properties. In other perspective, it is necessary to understand the behavior of the stimulated formation. By understanding these rock properties, it is possible to do some simulation of the hydraulic fractures propagation, proppant performance and finally production efficiency (Quosay and Knez 2016; Knez and Mazur 2019; Quosay et al. 2020).

One of the benefits of understanding the mechanical properties of rock is the better interpretation the well-logging (Alexeyev et al. 2017). There are two kinds of measurement involving the understanding of these poroelastic rock properties, which are the static and dynamic measurement (King 1969, 1983; Fjær 2009; Rajaoalison et al. 2019). The dynamic moduli are obtained from the velocities of elastic waves and density, while the static moduli are derived from deformational experiments (Mavko et al. 2009). So, the static measurement involves external forces to understand the rock mechanical behavior, while the dynamic measurement uses acoustic waves, including compressional and shear waves. In this paper, the dynamic measurement is being used in order to understand the poroelastic properties behaviors of the rock samples, such as Poisson’s ratio (υ), Young’ modulus (E), and Biot’s coefficient. The applied load in porous rock is transmitted through the solid via granular contact by the fluid pressure (Ciccotti and Mulargia 2004; Sone and Zoback 2013; Rajaoalison et al. 2020). The concept of effective stress, widely used in geomechanics, has been introduced by Terzaghi (Terzaghi 1936) and extended by Biot (1941). The relationship established by Terzaghi is limiting the case by rounding Biot coefficient to 1, while it varies between 0 and 1 based on rock properties, such as porosity but independents to fluid properties (Detournay and Cheng 1993; Gurevich et al. 2009). The contribution of the pore pressure to the effective stress is therefore quantified by the Biot’s coefficient. Besides, the heterogeneity, nonlinearity, and anisotropy of the rock are the key components of uncertainties of the accurate effective stress law model (Paterson and Wong 2005). As the Biot’s coefficient is considered as one of the keys factor in seismic analysis of porous media and the problems related to fluid substitutions (Gurevich et al. 2009), the assessment of such parameter is then important for the petroleum production prediction and helps to understand the distribution of the stress components in the wellbore wall as well as its surrounding.

In 1958 M. R. J. Wyllie, A. R. Gregory and G. H. F. Gardner established a relationship between the predicted values of P-wave velocity through saturated rock samples from the measured values through dry samples. The understanding of difference between predicted values from Wyllie’s theory and measured in saturated rock is very important as it helps to know the influences of saturation on rock properties and thus the behavior of saturated formation. The understanding of pore structure, lithology prediction, and seismic wave attenuation are the best practices of the Wyllie’s equation (Vernik 1994; Weger et al. 2004; Qadrouh et al. 2018). Apart from that, one of the most common laboratory tests in rock mechanic studies is the uniaxial or unconfined compressive test (UCS), which is used to estimate the compression rock strength. The UCS value depends strongly on water saturation (Vallejo et al. 1989; Shakoor and Barefield 2009) exhibiting water influence on the rock properties. In this paper, it is performed to confirm the saturation influence on rock strength.

This study shows the detailed assessment of the dynamic mechanical properties of Istebna sandstone under confining pressures, including Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and Biot’s coefficient at two different temperature levels. The UCS measurement will also be performed to estimate the strength of Istebna sandstone in dry and water-saturated samples. Finally, the poroelastic parameters through saturated samples will be predicted using the P-wave velocities from Wyllie’s equation in order to show the differences between measured and theoretical values. In this paper, the P- and S-wave velocities were measured in dry and water-saturated conditions. The measured P-wave velocities from dry samples were used to predict the P-wave velocities of saturated samples, as the Wyllie’s equation is only applicable to calculate the velocity of P-wave. As the poroelastic parameters are calculated using P- and S-wave velocities and density of the specimen, therefore the predicted P-wave velocities from Wyllie’s equation, S-wave velocities from dry samples, and density of samples are used to predict the poroelastic parameters, known as predicted values, while the P- and S-wave velocities of water-saturated samples are used to measure the poroelastic parameter, known as measured values.

Methodology

The mechanical properties of rock comprise elastic as well as inelastic properties (Baoping et al. 2005). The elastic properties refer to volume and shape resistance to deformation and as specified by Hooke’s law within small deformation (Eq. 1), in which the applied stress produces a proportional strain (Timoshenko and Goodier 1934). The dynamic Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are calculated using the Vs/Vp ratio and density of the rock sample by considering it as isotropic and linear elastic (Eqs. 2, 3) (Bailin 2001; Guo and Liu 2014; Rajaoalison et al. 2020):

where σ is the stress [Pa], ε is the strain [kg/cm3], VP is the velocity of P-wave [m/s], VS is the velocity of S-wave [m/s], ρ is the bulk density [kg/m3] that is ranging from 2.64 to 2.69 kg/m3 for the studied samples, ν is the Poisson’s ratio [−], and E is the Young’s modulus [Pa].

Biot’s coefficient α is also known as effective stress coefficient (Eq. 4):

where KS is the bulk modulus and K0 is the bulk modulus of solid matrix [in Pa]. The bulk modulus of solid matrix (K0) is measured on unjacketed specimen where the pore pressure is equal to confining pressure (Franquet and Abass 1999), while the bulk modulus, KS, is measured on jacketed specimen where the pore pressure is equal to zero and using Eq. 5:

The relationship developed by Wyllie et al. (Eq. 6) is used to estimate the dynamic values of saturated samples using the measurement from dry samples and thus the related parameters (Eqs. 2–5) in saturated condition (Wyllie et al. 1956, 1958):

where VPpred is the predicted velocity of P-wave through saturated rock, Vf is the velocity of P-wave through fluid [m/s], Vm is the velocity of P-wave through rock matrix [m/s], and Φ represents the porosity of the studied specimen [%]. It is a dimensionless parameter between 0 and 1 and it is sometimes expressed in % (Collins and Jordan 1961). The porosity differs from one geological material to another based on the grain sizes, their orientation, as well as the presence of fractures. In this paper is used the total porosity. From the time-average equation (Eq. 6), the total porosity can be calculated using Eq. 7, in which the rock samples are considered as homogeneous, isotropic, and fluid saturated (Wyllie et al. 1956, 1958):

where Vf is the P-wave velocity through liquid, Vm is the P-wave velocity through rock matrix, and VP is the P-wave velocity through saturated samples, in which Vf = 1500 m/s that is through water and Vm = 4230 m/s is the P-wave velocity through the studied sandstone rock matrix.

Laboratory measurement

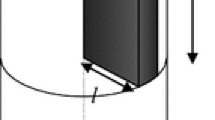

The measurement in this research has been conducted on Vinci technology AVS 1000 apparatus. This equipment is used to perform ultrasonic P- and S-wave velocity measurements, composed of parametric pulsar, Tektronix digitizing oscilloscope, and sonic platens containing P- and S-wave transducers as well as receivers. The travel time of the P-wave and S-wave are being recorded and their velocities are calculated accordingly by dividing the sample length by the travel time in seconds (Rao et al. 2006). Both ends of the samples were polished and lapped parallel up to ± 0.2 mm in order to minimize the error and protect the seal from damage due to higher stress. Also, the cylindrical sides are made straight with an accuracy of ± 0.3 mm over the full length of each specimen. High frequency signals of approximately 1000 kHz and 500 kHz for compressional and shear waves, respectively, were used in this ultrasonic equipment, and the system was calibrated using aluminum and copper samples with known velocities. A schematic diagram of the AVS system for dynamic mechanical properties measurements is shown in Fig. 1.

The moisture trapped in the sample was removed by placing it in an electrical oven at 105 °C for more than 24 h; however, some part of bound water is still trapped in the core. Afterward, the core is cooled at room temperature and the density of each sample is calculated using the mass and bulk volume.

Origin of studied samples

The Istebna formation belongs to the Silesian Unit, which is located in the Polish Outer Carpathians, in the southern part of Poland, near to the border between Poland, Czech Republic, and Slovakia. It is also called as the Silesian Nappe. The Moravskoslezske Beskidy Mts, to Beskid Mały Mts in Poland, till the Silesian Beskid Mts in the western part of the Czech Republic is the extension of this formation and it is formed the Western Beskids mountains (Lexa et al. 2000; Strzeboński et al. 2017). The Istebna formation is formed by the superposition of two members of rock that are the Czarna Wisełka member (Lower Istebna Beds) with a thickness of 1500 m at the bottom and the Janoska, Jasnowice, and Kamesznica members (composed of Lower Istebna shales, upper Istebna sandstones, and upper Istebna shales part of Upper Istebna Beds) with a thickness of 400 m on the top (Burtanówna et al. 1937; Książkiewicz 1951; Starzec et al. 2018). The Istebna sandstone samples used in this research has been taken from the Sobolów open pit mine, which is part of the Janoska, Jasnowice, and Kamesznica members, with thickness from 1300 to 1600 m, (Strzeboński 2005). The micropaleontological data confirmed that the formation has been formed that was during the Late Cretaceous–Paleocene (Geroch 1960; Szydło et al. 2015) and its belt stretches from the vicinity of Wisła and Istebna in the Silesian Beskids, through Brzesko, Wadowice, Myślenice, Dobczyce, Nowy Sącz, and up to Sanok. A sand-dominated unit represents the lithostratigraphic of the Istebna sandstone and it is mostly formed with thick-bedded, coarse-grained sandstones and granule/fine-pebble conglomerates, and intercalated with packets of fine-grained sandstone–shale (Strzeboński 2005; Grzebyk 2006; Strzeboński et al. 2017).

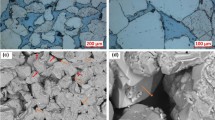

The Istebna samples used for the dynamic mechanical properties and uniaxial compressive strength measurements in this study were acquired from Sobolów open pit not weathered rock, cored in a perpendicular direction to bedding planes, which belonged to the upper Istebna sandstones of the Janoska, Jasnowice, and Kamesznica members. These samples had length of (40 ± 1) mm and diameter of 38 mm. These core samples were prepared and had smoothed surfaces according to the requirements in order to have a good coupling between the transducer and the receiver so that the transit time measurement of the arrival time of the waves will be more accurate, and the error due to geometry of the sample will be minimized (Fig. 2).

Results

All values presented in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6 present the dynamic poroelastic parameters of Istebna sandstone samples. The figures in these sections include the mean of the dataset with the standard deviation of the measured and predicted points. A simple linear regression using the least square method has been used to find the correlation between velocity waves, Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, Biot’s coefficient, and confining pressure. The porosity of the Istebna sandstone samples has ranged from 11.32 to 12.07%, with average value of 11.69%. The linear regression parameters related to these poroelastic values are presented in Table 1.

The variation of P-wave velocities through Istebna sandstone samples under confining pressure and temperature, as well as the difference between predicted and measured values, is shown in Fig. 3, in which the predicted values present the calculated water-saturated values of the studied parameter from measurement of dry samples using Wyllie’s equation, while the measured values are the measured values of saturated samples from experiments.

The primary P-wave is linearly positively correlated with confining pressure with a coefficient correlation of R2 = 0.98 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.97 at 80 °C for predicted values, while R2 = 0.99 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.99 at 80 °C for measured values. The variation of S-wave velocities through dry and saturated Istebna sandstone samples under confining pressure and temperature is shown in Fig. 4. The axis range of S-wave velocities in Fig. 4 is kept as similar as the axis range of P-wave velocities in Fig. 3, just to show that saturation does not have much effect on the S-wave velocities through the samples.

The S-wave velocity is linearly positively correlated to confining pressure with a coefficient correlation of R2 = 0.98 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.99 at 80 °C for dry, while R2 = 0.99 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.99 at 80 °C for saturated samples. The characteristic of Poisson’s ratio of Istebna sandstone samples, under confining pressure and temperature, as well as the difference between predicted and measured values, is presented in Fig. 5.

Poisson’s ratio is linearly negatively correlated to confining pressure with a coefficient correlation of R2 = 0.76 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.69 at 80 °C for predicted values, while R2 = 0.86 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.89 at 80 °C for measured. The characteristic of Young’s modulus of Istebna sandstone samples, under confining pressure and temperature, as well as the difference between predicted and measured values, is presented in Fig. 6.

Young’s modulus is linearly positively correlated with confining pressure with a coefficient correlation of R2 = 0.99 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.99 at 80 °C for predicted values, while R2 = 0.98 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.99 at 80 °C for measured values. The characteristic of Biot’s coefficient of the Istebna sandstone samples under confining pressure and temperature, as well as the difference between predicted and measured, is presented in Fig. 7.

Biot’s coefficient is linearly correlated to confining pressure with a coefficient correlation of R2 = 0.83 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.86 at 80 °C for predicted values, while R2 = 0.92 at 20 °C and R2 = 0.88 at 80 °C for measured values. The experimental results of the uniaxial compressive strength of dry and water-saturated Istebna sandstone samples that has been carried out under the rate of 1 kN/s in compressing apparatus are presented in Fig. 8.

Discussion

All discussion and conclusions are valid only for the investigated rock and in the measurement ranges presented in the paper. The P-wave as well as S-wave velocities are proportional to confining pressure (Figs. 3, 4). This happens because of micro-fractures closing and pore space decreasing during the increase in confining pressure. The range of predicted P-wave velocities varies from 2800 to 3500 m/s, while the ones measured in the laboratory vary from 3900 to 4500 m/s. However, the increase in temperature slightly decreases the P-wave velocities in the rock samples. It is important to notice that the Wyllie’s equation is only applicable for predicting the P-wave velocities through saturated samples from the P-wave velocities through dry samples. Thus, the ratio between predicted VP and VS through dry samples are used to calculate the Poisson’s ratio and Young modulus of Istebna sandstone samples. Besides, the increased temperature was slightly decreasing the value of S-wave velocity and the saturation did not show any significant changes. The S-wave velocity ranges through both dry and saturated Istebna sandstone samples are nearly similar and vary from 1500 to 2000 m/s.

P-wave as well as S-wave velocities are then affecting the rock poroelastic parameters. A good correlation between Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, and confining pressure has seen and the increasing temperature slightly decreased their values (Figs. 5, 6). The range of Poisson’s ratio varies from 0.26 to 0.30 for predicted values and from 0.36 to 0.41 for measured values, while Young’s modulus varies from 1.60 to 2.60E + 10 Pa for predicted values and from 2.20 to 2.70E + 10 Pa for measured values. Moreover, Biot’s coefficient is negatively correlated to confining pressure with a good correlation coefficient. As the temperature increases so does the value of this parameter (Fig. 7). The Biot’s coefficient of the studied specimen ranges from 0.16 to 0.42 at 20 °C and from 0.24 to 0.48 at 80 °C.

Figures 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 show a clear difference between measured values and the values predicted from Wyllie’s equation. Such apparent disagreement could be the result of the changes of rock mechanical properties due to rock matrix interaction with water. To check it, a simple UCS test was performed. The unconfined compressive strength has been performed with Istebna sandstone, in dry and water-saturated condition, in order to check the saturation effects on rock strength. The ranges of maximum stress the specimen can bear under uniaxial confining pressure are shown in Fig. 8. The strength of dry samples is almost twice that of the strength of water-saturated samples. The maximum stress for dry samples ranges from 103.95 to 114.87 MPa with an average value of 108.80 MPa, while the maximum stresses for water-saturated samples range from 57.84 to 63.14 MPa with average value of 60.97 MPa. Such difference clearly shows the effect of water saturation on sample strength and also confirms the difference observed between predicted and measured values in the above parameters, including P-wave velocities, Poisson’s ratio, Young’s modulus, and Biot’s coefficient. Water influences not only P-wave velocities according to Wyllie’s equation but also acts as a weakening substance according to UCS measurements. Lines for predicted and measured Poisson's ratio (Fig. 5) are parallel so water saturation influences in the same degree its value for low and high confining pressure. However, Young’s modulus (Fig. 6) for higher confining pressure is quite similar for both predicted and measured values. Opposite for Biot's coefficient (Fig. 7), there is higher discrepancy with Wyllie’s equation for high confining pressure. Temperature was found to have minor impact on poroelastic properties (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) comparing to confining pressure and weakening effect of water saturation in Istebna sandstone. In many purposes for petroleum projects such as drilling mud filtration and oil–water contact movement, water saturation is changing. In Istebna formation with water substitution in the pore space, it is better to use measured poroelastic parameters instead of predicted from Wyllie’s equation due to weakening effect in rock matrix.

Conclusions

Based on findings, we can conclude that:

-

1.

The discrepancy of predicted values using Wyllie’s equation and measured during experiments is due to the weakening effect and therefore shows differences in P-wave velocities as well as in the related dynamic mechanical parameters, confirmed by the UCS for dry and water-saturated Istebna sandstone samples.

-

2.

The closing and opening of cracks and micro-fractures within specimen while increasing the confining pressure affect the values of P-wave velocity and thus dynamic parameters of Istebna sandstones.

-

3.

P-wave velocity and Young’s modulus have a positive correlation with the increasing confining pressure, while the Poisson’s ratio and Biot’s coefficient are decreasing with the increasing confining pressure in the Istebna sandstone.

-

4.

Temperature has minor effect on P- and S-wave velocities, Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio values. However, measured values of Biot’s coefficient clearly increase with increasing temperature.

-

5.

The uniaxial compressive strength of dry Istebna sandstone is about 50% stronger than in water-saturated condition.

Availability of data and material

All relevant data are within the paper.

References

Ahmed MA, Hegab OA, Sabry A (2016) Early detection enhancement of the kick and near-balance drilling using mud logging warning sign. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci 3:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejbas.2015.09.006

Alexeyev A, Ostadhassan M, Mohammed RA, et al (2017) Well log based geomechanical and petrophysical analysis of the bakken formation. In: 51st US Rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium. American Rock Mechanics Association

Bailin W (2001) Boit’s effective stress coefficient evaluation: static and dynamic approaches. In: ISRM international symposium-2nd Asian rock mechanics symposium. International Society for Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering

Baoping L, Jinan T, Hongjian L et al (2005) Structure and infrared emissivity of polyimide/mesoporous silica composite films. J Solid State Chem 178:650–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2004.12.010

Biot MA (1941) General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J Appl Phys 12:155–164. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1712886

Burtanówna J, Konior K, Książkiewicz M (1937) Carte géologique des Karpates de Silésie

Ciccotti M, Mulargia F (2004) Differences between static and dynamic elastic moduli of a typical seismogenic rock. Geophys J Int 157:474–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2004.02213.x

Collins RE, Jordan JK (1961) Porosity and permeability distribution of sedimentary rocks. SPE-212-MS 29

Detournay E, Cheng AH-D (1993) Fundamentals of poroelasticity. In: Analysis and design methods. Elsevier, pp 113–171

Fjær E (2009) Static and dynamic moduli of a weak sandstone. Geophysics 74:103–112. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3052113

Franquet JA, Abass HH (1999) Experimental evaluation of Biot’s poroelastic parameter Three different methods. In: Vail Rocks 1999, The 37th US symposium on rock mechanics (USRMS). American Rock Mechanics Association

Geroch S (1960) Microfaunal assemblages from the Cretaceous and Palaeogene Silesian unit in the Beskid Slaski Mts. Western Carpathians Biuletyn Instytutu Geologicznego 153:7–138

Grzebyk J (2006) New data on heavy minerals from the Upper Cretaceous-Paleogene flysch of the Beskid Œl1ski Mts. (Polish Carpathians). 15

Guo J, Liu Y (2014) A comprehensive model for simulating fracturing fluid leakoff in natural fractures. J Nat Gas Sci Eng 21:977–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2014.10.020

Gurevich B, Makarynska D, Pervukhina M (2009) Ultrasonic moduli for fluid-saturated rocks: Mavko-Jizba relations rederived and generalized. Geophysics 74:N25–N30. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3123802

King MS (1969) Static and dynamic elastic moduli of rocks under pressure. In: The 11th US symposium on rock mechanics (USRMS). American Rock Mechanics Association

King MS (1983) Static and dynamic elastic properties of rocks from the Canadian Shield. Intl J of Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abs 20:237–241

Knez D (2014) Stress state analysis in aspect of wellbore drilling direction. Arch Min Sci 59:71–76. https://doi.org/10.2478/amsc-2014-0005

Knez D, Calicki A (2018) Looking for a new source of natural proppants in Poland. Bull Pol Acad Sci Tech Sci 1:2. https://doi.org/10.24425/119052

Knez D, Mazur S (2019) Simulation of fracture conductivity changes due to proppant composition and stress cycles. Inżynieria Mineralna 21:

Knez D, Wiśniowski R, Owusu WA (2019) Turning filling material into proppant for coalbed methane in Poland—Crush test results. Energies 12:1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12091820

Książkiewicz M (1951) Explanations to the general geological map of Poland 1: 50,000. Wadowice Sheet 1–272

Lexa J, Bezák V, cko ME, et al (2000) Geological map of Western Carpathians and adjacent areas 1: 500 000. Geological Survey of Slovak Republic, Bratislava

Li Q, Aguilera R, Cinco Ley H (2019) A Correlation for Estimating Biot Coefficient. In: SPE Western Regional Meeting. Society of Petroleum Engineers, San Jose, California, USA

Mavko G, Mukerji T, Dvorkin J (2009) The rock physics handbook, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Messori A, Volonté G, Figoni A, Pellegrino A (2019) Experimental procedures for the evaluation of Biot’s coefficient of low porosity carbonates. In: Offshore Mediterranean Conference 11

Paterson MS, Wong T (2005) Experimental rock deformation-the brittle field. Springer, Berlin

Qadrouh AN, Carcione JM, Ba J et al (2018) Backus and Wyllie averages for seismic attenuation. Pure Appl Geophys 175:165–170

Quosay AA, Knez D (2016) Sensitivity analysis on fracturing pressure using Monte Carlo simulation technique. Oil Gas European Magazine 42(3):140-144

Quosay AA, Knez D, Ziaja J (2020) Hydraulic fracturing: New uncertainty based modeling approach for process design using Monte Carlo simulation technique. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236726

Rajaoalison H, Knez D, Zlotkowski A (2019) Changes of dynamic mechanical properties of brine-saturated Istebna sandstone under action of temperature and stress. Przem Chem 98:801–804. https://doi.org/10.15199/62.2019.5.22

Rajaoalison H, Zlotkowski A, Rambolamanana G (2020) Mechanical properties of sandstone using non-destructive method. J Min Inst 241:113–117. https://doi.org/10.31897/PMI.2020.1.113

Rao M, Lakshmi KP, Sarma LP, Chary KB (2006) Elastic properties of granulite facies rocks of Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. J Earth Syst Sci 115:673–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-006-0005-z

Shakoor A, Barefield EH (2009) Relationship between unconfined compressive strength and degree of saturation for selected sandstones. Environ Eng Geosci 15:29–40. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.15.1.29

Sone H, Zoback MD (2013) Mechanical properties of shale-gas reservoir rocks—Part 1: static and dynamic elastic properties and anisotropy. Geophysics 78:D381–D392. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2013-0050.1

Starzec K, Waśkowska A, Golonka J et al (2018) Rocky sandstone landforms in Istebna, Silesian Beskid (Outer Carpathians, Poland). Geotourism/Geoturystyka. https://doi.org/10.7494/geotour.2018.52-53.2

Strzeboński P (2005) Cohesive debrites of the Istebna Beds (Upper Senonian–Paleocene) west of the Skawa River. Kwart 31:201–224

Strzeboński P, Kowal-Kasprzyk J, Olszewska B (2017) Exotic clasts, debris flow deposits and their significance for reconstruction of the Istebna Formation (Late Cretaceous – Paleocene, Silesian Basin, Outer Carpathians). Geol Carpath 68:562–582. https://doi.org/10.1515/geoca-2017-0037

Szydło A, Słodkowska B, Nescieruk P, Strzeboński P (2015) Microfossils from the Istebna beds: implications for stratigraphy and depositional environment. In: 16th Czech-Slovak-Polish Palaeontol. Conf. and 10th Polish micropalaeontol. workshop, pp 74–75

Terzaghi K (1936) Stress distribution in dry and in saturated sand above a yielding trap-door. Intl Conf Soil Mech Proc I:307–311

Timoshenko SP, Goodier JN (1934) Theory of elasticity. MaGraW․ Hill Inc, New York

Vallejo LE, Welsh Jr RA, Robinson MK (1989) Correlation between unconfined compressive and point load strengths for Appalachian rocks. In: The 30th US symposium on rock mechanics (USRMS). American Rock Mechanics Association

Vernik L (1994) Predicting lithology and transport properties from acoustic velocities based on petrophysical classification of siliciclastics. Geophysics 59:420–427

Weger RJ, Baechle GT, Masaferro JL, Eberli GP (2004) Effects of porestructure on sonic velocity in carbonates. In: SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2004. Society of Exploration Geophysicists, pp 1774–1777

Wyllie MRJ, Gregory AR, Gardner GHF (1958) An experimental investigation of factors affecting elastic wave velocities in porous media. Geophysics 23:459–493. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1438493

Wyllie MRJ, Gregory AR, Gardner LW (1956) Elastic wave velocities in heterogeneous and porous media. Geophysics 21:41–70. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1438217

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the AGH University of Science and Technology, Krakow, Poland, and AGH–UNESCO support.

Funding

The project was supported by the AGH University of Science and Technology, Krakow, Poland subsidy 16.16.190.779 and AGH–UNESCO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors were contributing to data acquisition and writing of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Michal Malinowski (CO-EDITOR-IN-CHIEF)/Jadwiga Anna Jarzyna, prof (ASSOCIATE EDITOR).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knez, D., Rajaoalison, H. Discrepancy between measured dynamic poroelastic parameters and predicted values from Wyllie’s equation for water-saturated Istebna sandstone. Acta Geophys. 69, 673–680 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-021-00543-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-021-00543-3