Abstract

We present empirical evidence that large structural shocks are followed by changes in labor market inequality. Specifically, we study short-run fluctuations in adjusted gender wage gaps (unequal pay for equal work) following episodes of structural shocks in the labor markets, using several decades of individual data for a wide selection of transition countries. We find that for cohorts who entered the labor market after the onset of transition. Labor market shocks lead to significant declines in the gender wage gap. This decrease is driven mostly by episodes experienced among cohorts who enter the labor market during the transition. By contrast, we fail to find any significant relation for cohorts already active in the labor market at the time of transition. We provide plausible explanations based on sociological and economic theories of inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

From a sociological perspective, discrimination typically derives from power differences, which, in turn, derive from the positions that the privileged and the disfavored occupy in a society Reskin and Bielby 2005). Theories of conflict, segregation (Bergmann 1974; Bielby and Baron 1984; Collins et al. 1993; Cohen 2011), and feminization (Weisberg 1993; Douglas 1998), among others, theorize why women do not receive equal pay for equal work. The economic view of inequality distinguishes between unevenness rooted in underlying productivity differentials and inequity which cannot be explained away by objective differences in productivity-related characteristics and thus is attributed to tastes (Becker 1957; Krueger 1963; Phelps 1972; Stiglitz 1973; Ashenfelter and Oaxaca 1987).Footnote 1 A large body of research in social sciences documents a (slow) decline in adjusted gender wage gaps (Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer 2007). Both sociology and economics view inequality as a result of relatively slow-moving institutions (Roland 2008). Changes in inequality follow from changes in agency and structure (sociological view) or shifts in tastes (economic view), none of which is rapid. Neither field of research paid much attention to short-run fluctuations.

Our objective in this study is to inspect the relationship between short-term fluctuations in adjusted gender wage gaps (AGWG) and rapid structural change. We focus on gender wage gaps not only due to its paramount policy relevance but also because gender equality is relevant for each economy, whereas some countries might lack sufficient representation (and data coverage) of, e.g., minorities. We hypothesize that the scope of inequality rises when the labor market undergoes a rapid structural change, i.e., periods of massive labor reallocation. We further propose that the link between massive labor reallocation and gender wage inequality is particularly strong for those who are more exposed to these large structural shocks.

Note that our hypothesis refers to wage differentials among workers, i.e., after both men and women obtained employment. Meanwhile, the leading explanations of gender inequality refer to either the ability to obtain a given job (e.g., segregation theory), job characteristics (e.g., feminization theory), and labor supply decision given prevailing social norms (conflict theory in sociology and household bargaining in economics). Finally, economics explains wage inequality by differences in bargaining power vis-a-vis employers across groups. While workers may lose their bargaining power vis-a-vis employers during periods of large structural shocks, it remains unclear why this process should be systematically more prevalent among women. Given their role as secondary earners, women may have a higher reservation wage and thus remain out of employment rather than be underpaid. Against this background, our research innovates by focusing on adjusted gender wage gaps: wage differentials between men and women in employment relationships, identical in terms of observed characteristics relevant for productivity.

We structure the empirical strategy to provide evidence on potential links between rapid structural change in the labor market and gender wage gaps. Abstracting from the social norms as an explanation requires working with data from many countries and over several years. One also needs to observe some massive labor reallocations during these years. Finally, one needs to measure adjusted gender wage gaps before, during, and after the structural change. Our empirical strategy matches these requirements. We obtain individual level data for thirteen Central and Eastern European countries over a period spanning nearly two decades and estimate adjusted gender wage gaps.Footnote 2 During this time, these thirteen countries underwent a massive labor reallocation induced by a transition from a centrally planned system to a market economy, which allows us to identify episodes of large structural change.

The remainder of our paper is structured as follows. We begin by presenting the relevant literature with a focus on two main points: the theoretical underpinnings of gender inequality and the previous empirical findings in the field. In the subsequent section, we carefully describe the data and method used in this study. This section also introduces the Life in Transition Survey, which we use to measure episodes of large structural shocks in the labor market. In Sect. 3.4, we describe the estimated adjusted gender wage gaps in the thirteen countries. Finally, in Sect. 4, we discuss the relationship between gender wage gaps and large structural shocks in the labor market.

2 Structural Change and Wage Gaps: Theories and Facts

2.1 Theoretical Explanations for Gender Inequality

Most sociological theories place societal norms at the root of gender inequality, as norms define modes of behavior that are consistent with a gender division of labor and power. In particular, approaches emerging from the conflict theory tradition emphasize the element of subordination, and approaches emerging from stratification theory emphasize a variety of outcomes that differ in parallel to wages and labor market status (see Seguino 2007 for a general exposition). Women from societies holding more traditional gender values are less able to take advantage of arising opportunities (e.g. Fernandez and Fogli 2009; Alesina and Giuliano 2010). Women who live in areas where traditional gender norms are more prevalent have worse economic outcomes, even if they do not share those values themselves (e.g. Charles et al. 2018). According to the segregation theory, many cultures impose specific spaces where individuals are not allowed to function at par, which spills to other spheres of society, including the labor market. Feminization theory adds that some of those segregationist norms display in women being allowed to work only in occupations consistent with their lower status. This approach suggests that access to jobs is unequal between men and women. The taste-based theory of inequality, started by Becker (1957), argues that if the privileged group in the society has a distaste for some other groups, then privileged workers may require to be compensated for the discomfort of being in contact. Inequality stems from women’s co-workers demanding compensation for sharing the work environment with women, or from clients of firms being compensated for the disutility of receiving service from women. This approach suggests that pay can be unequal even if men and women perform the same work.

The strong link between gender norms and women’s labor market outcomes hints that changes in norms may trigger a change in gender inequality. Indeed, empirical literature consistently finds that once the norms change towards greater equality, the relative position of women in the labor market improves as well (see a thorough review by Bertrand 2011). The evolution of gender norms, and the reasons behind its change, have been debated in the literature. Following the so-called modernization hypothesis, the change in material conditions has led to more egalitarian gender norms from very different positions. Inglehart and Norris (2003) suggest that wealth levels reached by Western societies stood behind the emergence of postmodern values as of the 1970s. Focusing on the labor market, Seguino (2007) and Fernandez (2013), among others, study changes in employment and expected earnings, respectively, and argue in favor of a virtuous circle where modernization allows better outcomes for women, which reinforces the original changes in the gender norms.Footnote 3 Causality, thus, runs both ways, but the process of adopting new norms is, by nature, slow-moving (Roland 2008). The slow-moving process serves to explain the slow decline in gender wage gaps observed by Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer (2007).

2.2 Structural Change and Gender Inequality

Little effort so far was put into analyzing the role of structural change in gender wage inequality. There has been some prior empirical work on cyclical fluctuations in wage inequality. However, this work focused mostly on raw wage differentials, not on the wage gaps adjusted for individual worker characteristics. For example, Biddle and Hamermesh (2013) argue that the relative wages of women follow business cycles in the US. They attribute the volatility in raw gender wage gaps to the higher cyclicality of wages among movers as opposed to those who do not change jobs (see also Hirsch and Winters 2014). These patterns, consistent with segregation theory and to some extent with feminization theory, reflect adjustments solely in raw gender wage gaps. These patterns remain silent about changes in actual inequality.

The transitory structural reallocation of production in war periods appears as a useful case study. Some rise in the labor market participation of women observed in many countries during World War II has proven to be permanent (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2004; Fernández et al. 2004; Goldin and Olivetti 2013) and has lead to important changes on the role of women (e.g. Walby 2003; Summerfield 2013). However, little is known about how the war-related structural shock affected gender wage inequality because high-quality data on both wages and worker flows is lacking.

2.3 Experience of Transition Countries

The structural shock experienced by the countries transitioning from centrally planned to a market-based system in Central and Eastern Europe can help to fill the lagoon in the empirical literature. First, shocks were sudden and thorough. The average GDP drop in 1992 relative to the pre-1989 level amounted to as much as 20%. More importantly, the shock was exogenous. Labor market participants could not account for the onset of transition in their educational, nor occupational choices. Second, these countries were characterized by different starting points in terms of economic structure and human capital, which affected workers’ ability to adapt to new conditions. Third, centrally planned economies were characterized by relatively high participation rates, also among women, before the transition (Tyrowicz et al. 2018), and relatively equal wages across genders (King et al. 2017). Job security and child care availability minimize the conflict between family and professional obligations. Working hours were regular, while overtime was relatively rare (e.g. Fay and Frese 2000 for East Germany).

The thirteen countries under study constitute a historically and culturally diverse group of Central, Eastern, and Southern European countries. Indeed, during the period of study, one of the few characteristics shared by these countries was their transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based system. A second common feature is that, across these countries, women were encouraged to work under central planning, and wages were generally much more equal than in market economies (Tyrowicz et al. 2018). However, the attitude towards women was only egalitarian on the surface. Gender social norms in former socialist countries were, and still are, much less equal than in Western European economies (e.g. Seguino 2007). In a comparative volume, edited by Penn and Massino (2009), researchers find that despite important differences in former Soviet Block countries, the ruling party consistently displayed a paternalistic attitude towards women, which persists until today. In the World Values Survey, Eastern European respondents paint a portrait of women as second earners, less viable as leaders, and more dispensable as workers than respondents in Western Europe (Seguino 2007). While social norms identify that women should be the primary caregivers rather than fulfill their professional aspirations, they also mandate that women should participate in the labor market and help household income, see Fig. 2.

Indeed, centrally planned economies were characterized by higher female labor force participation and more frequent employment even among households with small children. However, these outcomes conflicted with prevailing social norms, and gradually the progressive outcomes were getting undone with the progress of the transition. The tension between agency and structure was particularly strong, and the systemic change of economic transition gave rise to substantial adjustments in wage schedules across genders (see for example Munich et al. 2005a, b for a comparison of wage schedules under central planning and market system in Czechoslovakia). A study on Germany and maternity leaves after reunification provides evidence in this direction (Boelmann et al. 2020). While some of the differences in social norms induced during central planning persist (rich literature studied the case of East and West Germany, e.g. Lee et al. 2007; Rosenfeld et al. 2004; Bauernschuster and Rainer 2012; Trappe et al. 2015; Boelmann et al. 2020), it appears that the structure dominated agency in a sense that superficial gender equality at the institutional level coexisted with low gender empowerment at a practical level.

The transition brought a substantial, and sharp, decline in employment.Footnote 4 The downward adjustment was larger for women (Blau and Kahn 1996). The asymmetric adjustment in men’s and women’s participation rates is consistent with a structural change in labor demand. In Germany, the fall in the raw gender wage gap occurred mostly due to workforce composition effects, i.e., a reduction in low-skill, low-paid jobs for women, and a substantial decrease in female participation rates (Hunt 2002). In Slovenia, strong cohort effects were observed, with younger women experiencing higher raw gender wage gaps than older women (King et al. 2017). Brainerd (2000) discusses the erosion of women’s social position in several Eastern European countries, specifically due to less adaptability and less competitive approach to career. Using panel data from seven transition economies, Brainerd (2000) analyses raw wage gaps for the same individuals for the period directly before and after the introduction of the major economic reforms. She finds that raw gender wage differentials grew. Similar conclusions are reached by Adamchik and Bedi (2003), Grajek (2003) for Poland, and Jolliffe and Campos (2005) for Hungary.

The literature on adjusted gender wage gaps for is less comprehensive, and the insights are rather mixed.Footnote 5 There is one common element, though: adjusted gender wage gaps tend to be higher than the raw gaps. However, direct comparisons of estimated adjusted gaps are difficult for two main reasons. First, estimation methods were different. Only some estimates adjust selection into employment, account for occupational segregation, etc. Moreover, outcome variables differ across estimates between hourly and monthly wages. Second, there are no studies, to the best of our knowledge, that would look systematically at all countries of the region and over time, rather than a narrow selection of countries at one point in time.

Against this rich literature, we innovate on several accounts. First, we provide a uniquely large collection of adjusted gender wage gaps estimates that are directly comparable across countries and over time. For this purpose, we harmonize individual level databases recovering a consistent measure of wages and individual workers’ characteristics. We also apply the same estimation methods across samples. Second, since centrally planned labor markets collapsed nearly overnight, we can benefit from studying cohorts active in the labor market prior to the onset of transition (born before 1965) and cohorts that only entered the labor market after 1990 (born after 1965). We hypothesize that the link between structural change and gender wage inequality is particularly strong for those who are more exposed to shocks. We exploit data availability for two cohorts of women and men: those working in the labor market already before the onset of transition, and those who entered the labor market later on. Third, we study rigorously the links between massive labor market flows—the structural change in the labor market—and the gender inequality in wages.

3 Data and Methods

We collect data for a broad list of countries from Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. To obtain measures of structural change and labor market adjustment, we utilize a dataset developed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Life in Transition survey (LiT), which is available for 29 countries between 1989 and 2006. We describe this in detail in Sect. 3.1. We also acquire individual level data for these countries, which we describe in Sect. 3.3. We discuss harmonization and obtaining the measures of adjusted gender wage gaps in Sect. 3.2. In Sect. 3.4 we describe the estimates of the adjusted gender wage gaps and the properties of our final data.Footnote 6

3.1 Measuring Labor Market Flows

To measure the massive labor market reallocations, we compute flow intensity measures from individual data in the LiT survey. The retrospective questionnaire from the LiT database provides information on the jobs held by workers in each year. This characteristic permits a direct identification of two gross worker flows separations and hirings.Footnote 7

The measures are expressed as a percentage of workers. Hirings is defined as the ratio between the number of new matches in a given year and the number of employees in the previous year. New matches refer both to movements out of unemployment, inactivity as well as to job-to-job flows. Separations refers to the probability of ending a match. Separations could occur either because the worker found a better position (job-to-job flows) or became unemployed or inactive.Footnote 8 “Hirings” indicate the proportion of new matches, whereas “separations” indicates the proportion of matches that are dissolved.

where \(E_i, E_j\) denote employments in positions with \(i \ne j\), and N refers to unemployment and inactivity in the working age.

Hirings and separations present an overall picture of the labor market churning. However, if we were to focus only on these flows, we would miss important questions related to how synchronized these flows were. We complement these measures with three conventional indicators of labor market reallocation: gross reallocation measure, net reallocation measure, and excess reallocation measure. Gross reallocation is defined as the sum of hirings and separations. This measure indicates the total number of flows experienced by an economy in a year. Net reallocation is defined as the difference between hirings and separations. This measure indicates whether employment grew in the country. Negative values indicate that the workforce shrank. Finally, excess reallocation is the difference between gross and (the absolute value of) net flows. This measure indicates the extent of labor market churning, i.e., the difference between all labor market flows and the flows needed to reach the new state. These worker flows are analogous to the job flows described in Davis and Haltiwanger (1992).

Following Hausmann et al. (2005), we identify episodes of rapid change in the reallocation indicators. Episodes of rapid change in a given labor market in a given year have to meet two criteria: the measure has high value in a given country (80th percentile as the threshold to define high values); and the measure grew 50% with respect to the previous year. Hence, our identification of episodes of rapid change is given by:

where lmflow denotes previously discussed measures of labor market flows.

We compute flow measures for male workers. This approach sidesteps the potential endogenous relation between women’s wages and women’s earnings patterns. Flow measures are computed for all working-age men, and separately for men in two birth cohorts: those who had labor market experience prior to the structural changes in the economy (cohorts born before 1965); and those who entered the labor market only after the onset of the structural changes (cohorts born after 1965). People born in 1965 are 25 years old in 1990, which is the age of labor market entry for tertiary-educated individuals. Workers without a university degree would have at most a few years of employment experience.

Table 1 reveals the value of distinguishing between cohorts. Cohorts born after 1965 are characterized by higher hiring rates, relative to cohorts born before 1965. By contrast, separations appear to be quite similar across cohorts, which results in the negative net changes for cohorts born before 1965, some of them related to retirement. Values of excess suggest that cohorts born after 1965 experienced more fluctuations in career patterns. This pattern indicates that workers from earlier cohorts tended to remain in more stable sectors and industries, e.g. public administration, and mostly left employment to retire. In spite of the differences in terms of labor market flows, there appears to be less evidence that cohorts born before and after 1965 differed in their transition patterns.

In total, we identify between 6 and 25 episodes of rapid labor reallocation matching the estimates of the gender wage gap, depending on the measure. The number of episodes of hirings is higher than the number of episodes of separations for both cohorts. For illustrative purposes, Fig. 3 shows the episodes of hirings and separations for all countries for which we were able to estimate the gender wage gap. We document substantial country-level heterogeneity both in terms of timing and in the number of episodes. For example, in Czech Republic, episodes appear to be more concentrated towards the end of the transition period; in Poland, episodes appear to be concentrated in the period 1995 to 2000; and, in Russia, episodes appear to be evenly split over time.

3.2 Measuring Gender Inequality

Raw wages are misleading as a measure of gender wage inequality if men and women differ systematically on their characteristics. For example, it is an empirical regularity that women in Central and Eastern European have much higher educational attainment than men. Holding everything else constant, this regularity suggests that women should receive higher wages than men. Consequently, adjusting wage distributions for men and women to account for differences in individual characteristics is of paramount importance. These adjustments are broadly referred to as decomposition methods because they serve to decompose wage differentials into an explained part (differences in individual characteristics) and an unexplained—or unjust—part. Adjusted measures of the gender wage gap require comparing men and women who are actually “alike” in terms of all relevant characteristics. The definition of what those characteristics are is both a conceptual issue and a data issue. In a comparative context, data availability (and their quality) often limits how many characteristics can be measured in a comparable way. The simplifications required can bias the estimates of the gender wage gap without providing much intuition on neither the size nor the sign of this bias.

Against this background, Ñopo (2008) formulated a non-parametric method to obtain the estimates of inequality, the adjusted gender wage gaps. Unlike parametric approaches, Ñopo (2008) decomposition is based on perfect matching. For each set woman with a given set of characteristics, the algorithm finds all exact matches among men. Then, it compares wages between men and women within this “cell” of identical individual characteristics. Such cells are defined by a combination of those individual characteristics. Once all gaps are computed, they can be aggregated to one measure of gender wage gap as a weighted average of all these gaps, where the weights come from the relative size of each “cell” in each labor market.

Clearly, some “cells” could contain only men or only women. The existence of these “cells” could reflect occupation segregation, different participation patterns, or men having a higher retirement age than women. A valuable feature of Ñopo (2008) decomposition is that it neither lumps these “cells” with the remaining observations, nor does it discard them. Instead, they can be used to infer how they affect gender wage gaps. The decomposition consists of four components: (i) a part that stems from the different proportions of men and women in each “cell”, which is typically referred to as explained part of the wage gap; (ii) a part that stems from the differences of wages between men and women within each “cell,” which is typically referred to as adjusted gender wage gap or unexplained part of the wage gap; (iii) a part that stems from the wage difference between men in men-only “cells” and men in other “cells”; and (iv) a part that stems from the wage difference between women in women-only “cells” and women in other “cells.”

This method is fully non-parametric because it is based on exact matching and because the weight of each “cell” comes from the relative size of those “cells” among women. Given that it obtains first estimates of the gender wage gap within “cells” containing few individuals with identical characteristics, we can expect that estimates of the adjusted gender wage gap are less susceptible to the presence of skewness in the wage distribution. Moreover, this method is particularly suitable to obtain wage gaps when labor markets are selective or segmented, which is very important from the perspective of our research question. Ñopo (2008) also has other advantages over other decomposition methods. This method provides the most reliable estimates when data limitations prevent the inclusion of a rich set of covariates. Plus, the components inform about the size and sign of the selection bias (Goraus et al. 2017). Finally, since it relies on exact matching, the risk of comparing a non-existent average man to a non-existent average woman is eliminated.

3.3 Harmonization of Earnings Data

We use data from the International Social Survey Program, Living Standard Measurement Surveys of the World Bank, and national labor force surveys. Data for some of the transition countries also come from the Structure of Earnings Survey. Overall, our collection of individual earnings data covers thirteen countries, comes from seven different sources, and spans 1990–2006. We review sources in Appendix 2. We acquired 150 datasets (countries/source/years) from transition countries with comprehensive information on wages that could be matched with data on worker flows. Table 5 describes in detail the source of data and the period covered for each of the analyzed countries.

Given the multiplicity of data sources, some compromise was necessary as to which variables are used for matching. Ñopo (2008) suggests that age, education, marital status, and urban/rural identification are sufficient to recover the gender wage gap adequately. From an empirical standpoint, the inclusion of additional covariates is not always possible. To ensure consistent definitions across databases, we decided to use broad categories within each database. Age was transformed into a categorical variable, where each category corresponds to five years. This approach follows the recommendations by Ñopo (2008) and Huber et al. (2013). Education was recoded into a three-level categorical variable, where levels correspond to less than secondary, secondary, and tertiary. Urban is a binary variable that takes the value of one when individuals live in agglomerations with over 20 thousand inhabitants. Finally, marital status takes only two values: in a relationship and single, regardless of the reason.

Having harmonized adjusting variables, we obtain a consistent definition of the outcome variable: gross hourly wages. Wages are either provided directly or derived from monthly wages. Databases that reported wages using categorical variables were excluded from the sample. In the final step, we compute the adjusted gender wage gaps using Ñopo (2008) independently for each database. Since we employ one decomposition method and always utilize the same set of control variables within each source, the resulting estimates are comparable. All estimations account for sample weights. Our final sample consists of measures of adjusted gender wage gaps (which we use as an indicator of gender inequality, i.e., unequal pay for equal work) for a given country in a given year.Footnote 9

In an effort to proxy for the exposure to the transition shock, we separate individuals into two groups: cohorts active in the labor market prior to the onset of transition (i.e., born before 1965), and the cohorts whose labor market initiation came at the period of structural change (i.e., born after 1965). We subsequently estimate the adjusted gender wage gap for each cohort of workers. Note that some of our databases were collected in the late 2000s, which implies that we observe pre- and post-transition cohorts many years after their labor market entry. Given that our adjusted gender wage gaps account for age, i.e., we only study wage differentials of men and women of the same age, splitting the sample by birth cohorts is, in principle, neutral to the measurement.

3.4 Adjusted Gender Wage Gap in Transition Economies

Table 5 reports the availability of individual level databases used to obtain measures of adjusted gender wage gaps. Overall, we obtain estimates of the adjusted gender wage gaps from 150 datasets for thirteen transition countries, for the period between 1990 and 2006. In a few cases (sixteen estimates in total), the adjusted gender wage gap estimates are negative (suggesting female advantage) or in excess of 100%. Our analysis continues with 134 observations, where the estimated adjusted gender wage gap is positive and below 100%. Due to data availability constraints, these 134 estimates are unevenly spaced, with occasionally more than one estimate for a given country in a given year and some gap years.Footnote 10 In Table 2 we report an estimate of gender wage inequality for each country. Given the variety of data and years available, we report country-level effects (i.e., averages adjusted for data sources and years available).

In Table 2, countries are ordered from the lowest to the highest adjusted gender wage gap for the whole population.Footnote 11 For some countries, the estimates are rather dispersed, and caution is required when inferring the typical prevalence of gender wage inequality. Dispersion is a concern in the cases of Serbia, Croatia, and Tajikistan. The gaps are the highest—25% or more—in Slovakia, Bulgaria, Latvia, Poland, Czechia, and Russia, a group highly diversified in terms of culture, religion, history, and geography. Romania and Slovenia are systematically characterized by adjusted gender wage gaps of 12%. Our estimates are roughly in line with the estimates provided by the earlier literature. Our estimates for Hungary are a little higher than those offered by Jolliffe and Campos (2005) because our decomposition method is more sensitive to segregation and selection into employment than the semi-parametric method used by Jolliffe and Campos (2005). Our estimates for Poland are in line with Adamchik and Bedi (2003), Goraus et al. (2017). Our estimates for Russia appear high, but prior literature has reported similar numbers (Dohmen et al. 2008).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the gender wage gap estimates for cohorts active before the transition and for cohorts that entered later on. Both raw and adjusted gender wage gap estimates are highly dispersed in our sample, with values ranging from almost nil to as much as 95% of men wages. As is standard in the gender wage gap literature on transition countries, adjusted gender wage gaps are greater than raw gaps. In other words, conditional on characteristics, women should earn more than men. While raw wage gaps are lower for the cohort born after 1965, the adjusted wage gaps are similar at the median across birth cohorts. Estimates hover around 23–25% of men’s wages at the median of our sample distribution. For the cohort born after 1965, estimates present a greater dispersion.

Estimates of the gender wage gap: raw (left) and adjusted (right). Data source: please refer to Table 5 for details on specific datasets for each country and year. Notes: We plot density of raw and adjusted gender wage gaps for all the individuals and when the estimates are obtained separately for cohorts born before and after 1965

Finally, we check the relevance of the non-overlapping distributions of men and women. In general, our matching leaves very few, close to none, individuals without a match. In 50% of the estimations, the percentage of unmatched individuals is below 1%. For a few databases, the percentage of matched men and women falls below 80%. Of course, even this small share of unmatched individuals could have a disproportional impact on the raw gender wage gaps. However, as shown in the columns denoted by \(\Delta _F\) and \(\Delta _M\), these components had a minor impact on the gender wage gap.

The data from Life in Transition survey are available for all transition countries between 1989 and 2006. We combine these two sources of data by country and year. We obtain 134 observations in total for estimates obtained on all birth cohorts. Likewise, for birth cohorts active in the labor market before the onset of transition (born before 1965), we can use 134 observations. For birth cohorts joining the labor market after the onset of transition, we have 128 matches between our adjusted gender wage gap estimates and measures of labor market flows obtained from Life in Transition survey.

4 Structural Change and Gender Wage Inequality

We present results in three substantive parts. First, we introduce our specification. Second, we report the obtained estimates and discuss them relative to the current literature. Finally, we discuss the consequences of some data limitations in our study.

Our approach to verify if episodes of massive labor market reallocation are associated with changes in adjusted gender wage gaps consists of two steps. We analyze the relationship between short-run dynamics of structural change and the (estimates of) adjusted gender wage gap. We estimate regressions of the following form:

where AGWG(c, ds, y) is a measure of the adjusted gender wage gap obtained for country c (thirteen countries in analysis), from data source ds (seven types of data sources) in year y (spanning 1990–2006, with gaps for adjusted gender wage gap measures, no gaps for labor market flow measures). The variable \(L_{c,i,j}\) indicates whether country c has experienced an episode of type \(i \in \, \{\text{hirings, separations, gross, net, excess}\}\) in any of the previous \(j \in \, \{1,2,3\}\) years. Then, \(\beta _1\) is the coefficient of interest. It shows the change in the measure of the adjusted wage gap following an episode. The remaining parameters \(\gamma _c\), \(\gamma _{ds}\), and \(\gamma _y\) indicate fixed effects for country, data source, and year. We cluster standard errors at the country-year level. Hence, the estimates are not susceptible to the fact that availability of data is greater in the case of some countries.Footnote 12 Overall, we estimate 45 independent regressions (three year lags \(\times\) three populations \(\times\) five flow measures). Note that countries in our sample experienced the episodes of rapid labor market flows at different years. Our specifications adjust for country-level specificity and time trends; hence the estimated coefficients identify the role of episodes rather than transition per se.

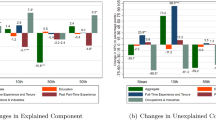

Table 3 presents the estimates of \(\beta _1\) for each regression. The episodes of massive structural change in the labor market correlate strongly with subsequent changes in the adjusted gender wage gaps for labor market entrants, but not for incumbents. A sudden hiring episode is associated with a decline in adjusted gender wage gaps for cohorts entering the labor market prior to the transition by as much as 14 percentage points, i.e., roughly as much as 50% of the gaps described in Table 2. The effects are stronger in the short run. Point estimates are smaller and less precisely estimated as time passes from the episode. The estimate of − 0.14 declines to roughly − 0.10, but these coefficients are not different from one another in statistical terms. The adjusted gender wage gap also declines following a net flow episode. However, the fall is slightly smaller in magnitude, around ten percentage points in the immediate aftermath and around eight percentage points two and three years after the episode. The cohorts who entered labor market after the onset of transition observe lower adjusted gender wage gaps also briefly after the episodes of gross and excess worker reallocations, but these effects are smaller in magnitude (roughly 6–7 percentage points). Unlike hiring and net episodes, the effects appear to be short-lived, especially for gross worker flows.

Among workers active prior to transition, the adjusted gender wage gap appears to be less sensitive to labor market flows. We systematically fail to reject the null hypothesis of no relation. Even though not statistically significant, it is interesting to notice that point estimates often have opposite signs to those obtained for younger cohorts. So, even though women in younger cohorts appear to benefit after the episodes of hirings, women in the older birth cohort appear to be worse off following a similar episode. The different reaction of the gender wage gap in the two subcohorts helps to explain why effects are mostly not significant when we run our specification for all birth cohorts jointly. We find some small, negative point estimates for lags of episodes in net worker flows, with a magnitude of roughly 2–3 percentage points.

The observed reduction in the adjusted gender wage gaps of younger cohorts following a structural shock may be due to several mechanisms. First, it could be that at the beginning of their careers, the youth of both genders receives fairly similar wages simply because they are low. This age-based explanation builds on the literature, which argues that gender inequality accumulates with the career. This explanation is corroborated by the adjusted gender wage gaps growing subsequent episodes in large gross labor market flows.

Second, it could be that labor market entrants differ from workers with established careers in terms of their outside options. Unlike cohorts already established in the labor market, those cohorts entering the labor market after transition lacked a “safe” alternative: whereas older cohorts could have accepted wage cuts and wage arrears in exchange for at least keeping the job, the younger cohorts did not have that choice, as they frequently searched their first employment. It appears that both young men and young women accepted similarly low offers. However, among older labor market participants, women accepted lower raises or higher wage cuts. Consequently, whereas a combination of self-selection and risk aversion could help to explain why gender wage gaps in cohorts active before the onset of transition are related to the labor market, they have little explanatory power among cohorts that entered the labor market afterward. If that mechanism is indeed at work, the bargaining theory explains only the adjustment for the birth cohorts active already prior to 1989, but not the mechanisms applying to the younger birth cohorts.

Finally, to the extent that women are considered secondary earners, their income might be perceived as less relevant for the household. Thus, one should expect women to have, all else equal, a higher reservation wage and accept relatively higher pay. This conjecture may explain why the adjusted gender wage gap declines after the hiring episodes: wage offer for young women has to rise (gender inequality declines) if they are to join the labor force. This result has both positive and negative interpretations. The positive interpretation relates to the outcomes: hiring episodes are conducive to more equality. The cynical interpretation relates to the mechanisms: the secondary earners are only participating if the primary earners consider their earnings worth the mental costs of seeing women employed. Prior theoretical literature did not preview for such short-run deviations from a general social norm.

Many studies argue that changes in gender wage inequality arise from fluctuations in employment: the composition of working men and working women changes over the business cycle. We study the adjusted gender wage gaps of those who stayed in employment. From the perspective of the bargaining theory, this channel may be particularly relevant for several reasons. First, change in women’s social position may display not only in employment status per se, but also in the ability to negotiate wage rises (especially in high inflation environment, as was the case in many countries in our study). Second, selection effects may be related to household optimization and represent a confounding of worker-employer relations with workers’ within household relations. However, once in employment, it is in households’ interest to maximize earned income. Hence, gender wage inequality fluctuating in the short run is not likely to display. Our paper is the first to empirically evaluate the link between short-run labor market fluctuations and adjusted gender wage inequality.

The transition countries offer a great natural experiment to study how large structural shocks in the labor market affect gender inequality, i.e., gender wage gaps adjusted for differences in characteristics. We hypothesized that periods of large structural change had an asymmetric effect on wages based on worker’s gender. Indeed, it appears that more labor flows tend to be less beneficial for women established in the labor market and more beneficial for newcomers in terms of wage inequality. Note that our results pertain to workers, so we refer to actual unequal pay for equal work. We thus innovate relative to the earlier literature in that we do not seek explanations in unequal employment across genders.

While the use of transition economies as a natural experiment is quite promising, data availability limits possible empirical strategies. First, one could be interested in splitting cohorts into more groups. However, data constrain our ability to stratify the samples further. Second, the lack of comparable data from all transition countries implies using databases of varying reliability. We took steps to moderate this concern: we harmonize the data, we include country and source fixed effects in the main specification, and we cluster standard errors at the country level. However, these steps only mitigate the risk that lower quality data drive our results. We cannot fully account for the possibility that in those countries and years for which data remains unavailable, the patterns were different from those identified in our study.

5 Conclusions

Gender wage differentials have garnished considerable attention from researchers worldwide. Notwithstanding, comparative studies remain rare; such analyses require micro-data sets that are relatively difficult to acquire and of varying quality. The few existing comparative papers either focus on the raw gap (e.g. Polachek and Xiang 2014) or employ meta-analysis techniques to control for differences in estimation procedure (e.g. Stanley and Jarrell 1998; Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer 2007). Our paper contributes to filling this gap. We employed a relatively robust non-parametric technique developed by Ñopo (2008) to provide comparable estimates for over 150 databases from transition economies over the past three decades. We utilize these estimates to provide insights on the link between structural shocks in the labor market and gender wage inequality.

Transition countries are a suitable case study, as they experienced a period of rapid adjustment of the labor market. These adjustments resulted from two simultaneous processes. First, economies transitioned from a probably overmanned and inefficient state-owned enterprises to private firms. Second, globalization forces demanded a reallocation of production away from manufacturing and into services. Perhaps more importantly, workers in those countries could not anticipate the collapse of the system when making their professional decisions. Using this setup, we seek to learn whether the churning resulting from this reallocation process affected men’s and women’s wages asymmetrically.

Our results suggest that a surge of hirings is associated with lower gender wage gaps, adjusted for individual characteristics, among cohorts that entered the labor market after the onset of transition. By contrast, for incumbent cohorts, the gender wage gap appears to increase following hiring episodes. In this case, wages had to increase in order to incorporate young women to the workforce with the consequent reduction in inequality. For cohorts already active, the option to leave might be less attractive. Another plausible explanation is related to an asymmetrically weakening of the bargaining position of workers who were established in the labor market prior to the transition: women may have been more prone to forego wage increases in the booming sectors in exchange for job stability.

Our results confirm that crises can have asymmetric effects in the labor market in a broader context, with stronger effects among groups in a disadvantageous position, such as women. Hence, our results could be interpreted as arguments in favor of targeting policies to cushion business cycle effects to specific groups. A possible example related to the skill obsolescence narrative from transition economies, could consist of maintaining gender quotas in re-skilling and activation programs targeted at nonemployed individuals.

Notes

In the remainder of this paper, the term “inequality” or “inequity” refers to unequal pay for equal work. We refer to overall wage differentials, which confound unequal work, unequal pay, and unequal workforce composition, as raw wage gaps. We interchangeably use the terms inequality and adjusted wage gaps to refer solely to unequal pay for equal work.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most extensive collection of such estimates. Ñopo et al. (2012) report results for a broader selection of countries but at one given year. A complete set of our estimates together with documentation may be downloaded from [http://grape.org.pl/article/when-opportunity-knocks-large-structural-shocks-and-gender-wage-gaps].

The emergence of authoritarian parties praising traditional norms can be thought both as a conservative reaction to previous changes and as a consequence of the deterioration of economic conditions in some Western countries Norris and Inglehart (2019).

Gender inequality did not increase rapidly during transition in Czech Republic (Munich et al. 2005a), but similar evidence comparing the same individuals before and after transition is scarce; for static, country-level analyses see Trapido (2007) for Estonia, Latvia and Russia, Adamchik and Bedi (2003), Goraus and Tyrowicz (2014) for Poland, Pastore and Verashchagina (2006) on Belarus, Dohmen et al. (2008) for Russia, Campos and Jolliffe (2003) on Hungary, Orazem and Vodopivec (1997) for Slovenia, Arabsheibani and Mussurov (2006) for Kazakhstan, Ganguli and Terrell (2006), Lehmann and Terrell (2006) for Ukraine; finally Gorodnichenko and Sabirianova Peter (2005) compare Russia and Ukraine.

A complete set of our estimates together with STATA code for replicating our results may be downloaded from [LINK].

Taking up a new job is not necessarily job creation (the position may be assumed after someone whose contract was terminated or the previous worker retired) and separation is not necessarily job destruction (the position may be immediately filled by someone else).

The distinction between unemployed and inactive is hard to recover in the LiT database, as workers were not asked about their search behavior during unemployment spells. This consideration also affected our decision to measure hirings as a percentage of the workforce instead of as the probability of finding employment.

On few occasions, we have more than one dataset available in a given country and year.

The discrepancies for the gender wage gaps between data sources do not exceed 10 percentage points and are consistent with the range of discrepancies reported by International Labor Organization in the Key Labor Market Indicators database. Typically, wage gaps are lower in data sets with larger number of observations (such as SES or LFS) than in other surveys, which may suggest that wage gaps are not the only dimensions of gender inequality in the labor markets. Moreover, the variance of the estimates appears to be lower in SES and LFS than in ISSP, consistent with the evidence from the description of the adjusted gender wage gap.

In some countries, the average adjusted wage gap for the population fall outside the estimates for the two subcohorts. This result is due to the filtering process. For a given country-year-source database, the adjusted gender wage gap of one subcohort might have been lower than 0% or higher than 100%, resulted in the discard of that subcohort, but not the other.

In an alternative specification, we weighted country \(\times\) year observations by the number of sources available. The estimated coefficients were robust to this manipulation. Results are available upon request.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D. H., & Lyle, D. (2004). Women, war, and wages: The effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at midcentury. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 497–551.

Adamchik, V. A., & Bedi, A. S. (2003). Gender pay differentials during the transition in Poland. The Economics of Transition, 11(4), 697–726.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2010). The power of the family. Journal of Economic Growth, 15(2), 93–125.

Arabsheibani, G. R., & Mussurov, A. (2006). Returns to schooling in Kazakhstan: OLS and instrumental variables approach. IZA Discussion Papers 2462, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Ashenfelter, O., & Oaxaca, R. (1987). The economics of discrimination: Economists enter the courtroom. American Economic Review, 77(2), 321–325.

Bauernschuster, S., & Rainer, H. (2012). Political regimes and the family: How sex-role attitudes continue to differ in reunified Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 25(1), 5–27.

Becker, G. S. (1957). The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Bergmann, B. R. (1974). Occupational segregation, wages and profits when employers discriminate by race or sex. Eastern Economic Journal, 1(2), 103–110.

Bertrand, M. (2011). Chapter 17: New perspectives on gender. In D. Card & O. Ashenfelter (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 1543–1590). New York: Elsevier.

Biddle, J. E., & Hamermesh, D. S. (2013). Wage discrimination over the business cycle. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 2(1), 1–19.

Bielby, W. T., & Baron, J. N. (1984). A woman’s place is with other women: Sex segregation within organizations. In Sex segregation in the workplace: Trends, explanations, remedies (pp. 27–55).

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (1996). Wage structure and gender earnings differentials: An international comparison. Economica, 63, S29–S62.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2003). Understanding international differences in the gender pay gap. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(1), 106–144.

Boelmann, B., Raute, A., & Schoenberg, U. (2020). Wind of change? Cultural determinants of maternal labour supply. mimeo, University College Lodon.

Brainerd, E. (2000). Women in transition: Changes in gender wage differentials in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54, 138–162.

Campos, N. F., & Jolliffe, D. (2003). After, before and during: Returns to education in Hungary (1986–1998). Economic Systems, 27(4), 377–390.

Charles, K. K., Guryan, J., & Pan, J. (2018). The effects of sexism on American women: The role of norms vs. discrimination, Working Paper 24904, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cohen, D. S. (2011). The stubborn persistence of sex segregation. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 20, 51.

Collins, R., Chafetz, J. S., Blumberg, R. L., Coltrane, S., & Turner, J. H. (1993). Toward an integrated theory of gender stratification. Sociological Perspectives, 36(3), 185–216.

Davis, S. J., & Haltiwanger, J. (1992). Gross job creation, gross job destruction, and employment reallocation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 819–863.

Dohmen, T., Lehmann, H., & Zaiceva, A. (2008). The gender earnings gap inside a Russian firm: First evidence from personnel data—1997 to 2002. Journal for Labour Market Research, 41(2/3), 157–179.

Douglas, A. (1998). The feminization of American culture. New York: Macmillan.

Fay, D., & Frese, M. (2000). Working in East German socialism in 1980 and in capitalism 15 years later: A trend analysis of a transitional economy’s working conditions. Applied Psychology, 49(4), 636–657.

Fernandez, R. (2013). Cultural change as learning: The evolution of female labor force participation over a century. American Economic Review, 103(1), 472–500.

Fernandez, R., & Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), 146–177.

Fernández, R., Fogli, A., & Olivetti, C. (2004). Mothers and sons: Preference formation and female labor force dynamics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1249–1299.

Ganguli, I., & Terrell, K. (2006). Institutions, markets and men’s and women’s wage inequality: Evidence from Ukraine. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34, 200–227.

Goldin, C., & Olivetti, C. (2013). Shocking labor supply: A reassessment of the role of World War II on women’s labor supply. American Economic Review, 103(3), 257–262.

Goraus, K., & Tyrowicz, J. (2014). Gender wage gap in Poland: Can it be explained by differences in observable characteristics? Central European Economic Journal, 36, 125–148.

Goraus, K., Tyrowicz, J., & van der Velde, L. (2017). Which gender wage gap estimates to trust? A comparative analysis. Review of Income and Wealth, 63(1), 118–146.

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Sabirianova Peter, K. (2005). Returns to schooling in Russia and Ukraine: A semiparametric approach to cross-country comparative analysis. Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(2), 324–350.

Grajek, M. (2003). Gender pay gap in Poland. Economics of Planning, 36(1), 23–44.

Hausmann, R., Pritchett, L., & Rodrik, D. (2005). Growth accelerations. Journal of Economic Growth, 10(4), 303–329.

Hirsch, B. T., & Winters, J. V. (2014). An anatomy of racial and ethnic trends in male earnings in the US. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(4), 930–947.

Huber, M., Lechner, M., & Wunsch, C. (2013). The performance of estimators based on the propensity score. Journal of Econometrics, 175(1), 1–21.

Hunt, J. (2002). The transition in East Germany: When is a ten-point fall in the gender wage gap bad news? Journal of Labor Economics, 20(1), 148–169.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jolliffe, D., & Campos, N. F. (2005). Does market liberalisation reduce gender discrimination? Econometric evidence from Hungary, 1986–1998. Labour Economics, 12(1), 1–22.

King, J., Penner, A. M., Bandelj, N., & Kanjuo-Mrcela, A. (2017). Market transformation and the opportunity structure for gender inequality: A cohort analysis using linked employer–employee data from slovenia. Social Science Research, 67, 14–33.

Kornai, J. (1980). Economics of shortage: Volumes A and B. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Kornai, J. (1994). Transformational recession: The main causes. Journal of Comparative Economics, 19(1), 39–63.

Krueger, A. O. (1963). The economics of discrimination. Journal of Political Economy, 71(5), 481–486.

Lee, K. S., Alwin, D. F., & Tufiş, P. A. (2007). Beliefs about women’s labour in the reunified Germany, 1991–2004. European Sociological Review, 23(4), 487–503.

Lehmann, H., & Terrell, K. (2006). The Ukrainian labor market in transition: Evidence from a new panel data set. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34(2), 195–199.

Munich, D., Svejnar, J., & Terrell, K. (2005a). Is women’s human capital valued more by markets than by planners? Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(2), 278–299.

Munich, D., Svejnar, J., & Terrell, K. (2005b). Returns to human capital under the communist wage grid and during the transition to a market economy. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(1), 100–123.

Newell, A., & Reilly, B. (1999). Rates of return to educational qualifications in the transitional economies. Education Economics, 7(1), 67–84.

Ñopo, H. (2008). Matching as a tool to decompose wage gaps. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(2), 290–299.

Ñopo, H., Daza, N., & Ramos, J. (2012). Gender earning gaps around the world: A study of 64 countries. International Journal of Manpower, 33(5), 464–513.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Authoritarian and populist values (pp. 85–212). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orazem, P. F., & Vodopivec, M. (1997). Value of human capital in transition to market: Evidence from Slovenia. European Economic Review, 41(3), 893–903.

Pastore, F., & Verashchagina, A. (2006). Private returns to human capital over transition: A case study of Belarus. Economics of Education Review, 25(1), 91–107.

Penn, S., & Massino, J. (2009). Gender politics and everyday life in state socialist Eastern and Central Europe. Berlin: Springer.

Phelps, E. S. (1972). The statistical theory of racism and sexism. American Economic Review, 62(4), 659–661.

Polachek, S. W., & Xiang, J. (2014). The gender pay gap across countries: A human capital approach, Discussion Papers 8603, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Porket, J. (1989). Overmanning. In J. Porket (Ed.), Work, employment and unemployment in the Soviet Union (pp. 114–143). Berlin: Springer.

Reskin, B. F., & Bielby, D. D. (2005). A sociological perspective on gender and career outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 71–86.

Roland, G. (2008). Fast-moving and slow-moving institutions. In J. Kornai, L. Matyas, & G. Roland (Eds.), Institutional change and economic behaviour (pp. 134–159). Berlin: Springer.

Rosenfeld, R. A., Trappe, H., & Gornick, J. C. (2004). Gender and work in Germany: Before and after reunification. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 103–124.

Seguino, S. (2007). Plus ça change? Evidence on global trends in gender norms and stereotypes. Feminist Economics, 13(2), 1–28.

Stanley, T. D., & Jarrell, S. B. (1998). Gender wage discrimination bias? A meta-regression analysis. Journal of Human Resources, 33, 947–973.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1973). Approaches to the economics of discrimination. American Economic Review, 63(2), 287–295.

Summerfield, P. (2013). Women workers in the Second World War: Production and patriarchy in conflict. London: Routledge.

Trapido, D. (2007). Gendered transition: Post-soviet trends in gender wage inequality among young full-time workers. European Sociological Review, 23(2), 223–237.

Trappe, H., Pollmann-Schult, M., & Schmitt, C. (2015). The rise and decline of the male breadwinner model: Institutional underpinnings and future expectations. European Sociological Review, 31(2), 230–242.

Tyrowicz, J., & Van der Velde, L. (2018). Labor reallocation and demographics. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(1), 381–412.

Tyrowicz, J., van der Velde, L., & Goraus, K. (2018). How (not) to make women work? Social Science Research, 75, 154–167.

Walby, S. (2003). Gender transformations. London: Routledge.

Weichselbaumer, D., & Winter-Ebmer, R. (2007). The effects of competition and equal treatment laws on gender wage differentials. Economic Policy, 22(50), 235–287.

Weisberg, D. K. (1993). Feminist legal theory: Foundations (Vol. 1). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to Julia Domagalik, Jakub Mazurek and Wojciech Hardy for their efforts in the data collection and data management process. We received extremely valuable comments from Saul Estrin, Randy Filer, Gianna Gianelli, Ekaterina Skoglund, Olga Popova, Richard Frensch, Joanna Siwinska, Tymon Sloczynski and Irene van Staveren as well as participants of AIEL, ECSR/EQUALSOC, EALE and TIMTED and seminars at University of Warsaw, Warsaw School of Economics. The remaining errors are ours. This research is a follow up of a seed grant funded by CERGE-EI under a program of the Global Development Network RRC 12. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of National Science Center (grant #2019/33/B/HS4/01645). Data collection and preliminary data analysis were commenced thanks to the support of NSC grant #2012/05/E/HS4/01510. Part of the work was conducted by Lucas van der Velde at the University of California, Berkeley whose hospitality is gratefully acknowledged. This study visit was sponsored by the Polish National Academy for Academic Exchange (#PPN/BEK/2018/1/00469)

Appendices

Appendix 1: Gender Norms in Transition Countries

Transition countries are characterized by more traditional social norms than advanced economies. Data source: International Social Survey Program, data for years 1994 and 2012. Notes: Given that the country composition changes between years in ISSP, we report in Fig. 2 the differential as the estimate of the \(\beta\) coefficient on the following regression: \(variable_i = \alpha + \beta *transition_i + \epsilon _i\), where the \(variable_i\) denotes a given measure of the social norm, \(transition_i\) denotes a dummy variable taking on the value of 1 for transition countries and 0 otherwise and \(\epsilon _i\) denotes random term. A positive indicator signifies that a higher share of men agree with a given statement in transition countries than in advanced European countries, adjusting for country composition effects. All estimates of \(\beta\) are highly statistically significant for each \(variable_i\), which is portrayed in Fig. 2 by the confidence intervals around the point estimate (the whiskers for each point estimate). As \(variable_i\) we use the answers to the following questions (in order of presentation at the figure): (i) Pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works; (ii) All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full time job; (iii) A job is all right, but what most women really want is a home and children; (iv) Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay; (v) Both the men and the women should contribute to household income. In all these questions, \(variable_i\) takes on the value 1 if respondents declare to agree or strongly agree with the statement, and 0 otherwise. Detailed results of the estimations are reported in Table 4

Appendix 2: Data

1.1 International Social Survey Program

The survey contains an internationally comparable roster with demographic, educational, labor market and household structure information. More importantly, database is available for transition countries already in early years after the collapse of the centrally planned system. Blau and Kahn (2003) profit from these features in their analysis of gender inequality.

1.2 Living Standards Measurement Survey

Developed by The World Bank, LSMS is a standardized household budget survey. Sample sizes for small countries participating in the LSMS program comprise about 10,000 observations, while in some cases the number of observations exceeds 30,000 individuals.

1.3 National Labor Force Surveys

As evidenced by Stanley and Jarrell (1998), studies based on LFS type of data are characterized by lower publication bias. Availability of relatively high quality data on hours actually worked implies hourly wages may be computed with higher precision, thus resulting in lower bias due to inadequate treatment of part-time or overtime. This data source is typically available for transition countries as of mid 1990s, but often wage data are not collected. We use LFS data for Serbia for years 1995–2002 and for Poland for years 1995–2006. In addition to these LFS, we also employ a similar database for Russia, the Longitudinal Monitoring Survey.

1.4 Structure of Earnings Surveys

Harmonized across countries, SES collects information on workers’ individual characteristics, hours worked and wages from employers. In comparison to alternative sources, SES provides the most detailed information for hours worked and compensations of different form (normal hours, additional hours, premia and similar). However, SES database lacks information on household structure and is only collected from the enterprise sector; in some countries, the sample is restricted further to cover only part of the enterprise sector, excluding e.g. small firms with less than 10 employees.

We use two such databases: Hungary SES, for the years between 1994 and 2006; and the EU-SES data, a harmonized data set that covers all EU Member States, and is released every fourth year since 2002 (Table 5).

Appendix 3: Additional Descriptive Statistics

Number of hirings and separation episodes per year: all cohorts.Notes: The vertical axes identifies whether an episode took place in that year (denoted by 1) or not (denoted by 0). The figure also indicates on which variable we recorded the episodes. Estimates for other countries/years and other measures available upon request

Appendix 4: Full Specification

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyrowicz, J., van der Velde, L. When Opportunity Knocks: Confronting Theory and Empirics About Dynamics of Gender Wage Inequality. Soc Indic Res 155, 837–864 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02620-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02620-y