Abstract

Nongovernmental stakeholders, including taxpayers and investors of government bonds, have an interest in government financial information. Fiscal transparency entails both access to and understandability of government information. Analyses of a government borrower’s financial information, often facilitated by market intermediaries, directly affect investor return on the bond market. In contrast, taxpayers may lack the incentive or capacity to comprehend government financial data prepared based on complex accounting rules. State fiscal monitoring programs compile and analyze local government financial data to track fiscal stress. This paper examines how housing and municipal bond markets respond to the New York monitoring program implemented in 2013, which uses existing, account-level local government financial data to assign simple labels signifying local government insolvency. Housing prices decreased following significant fiscal stress designations, but not statistically significantly following the other more modest stress labels. In contrast, the bond market priced in government financial information even before the state monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is important to distinguish between debt used to finance regular government operation and debt used to finance capital projects. While the former generates public services today, the later enables public services in the future as future taxpayers can continuously benefit from the infrastructure investment. Therefore, the capitalization of debt should only occur in the former situation.

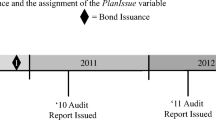

Local governments in New York have different fiscal year end dates and are divided into several groups based on their fiscal year calendars. The state reviews local governments with earlier fiscal year end date first and publishes label designations for each group accordingly. The exact date of a label designation is known. New York City is excluded from the state’s review.

The Comptroller’s office does make technical assistance, such as financial planning tools and online training, available to all local governments.

Localities follow the same accounting standards in preparing their financial data, a process that ensures comparability.

Because the state assigns fiscal labels based on cutoffs along an index score, a natural design to estimate the effect of label assignment is regression discontinuity (RD) analysis comparing observations just below and above a cutoff score. However, this study does not adopt a RD design for a few reasons. First, only around 50 localities are assigned a label each year and the number close to a particular cutoff is even smaller. Even though there are hundreds or thousands of property or bond sales, the number of localities around a cutoff, not the number of sales, determines the sample size. Therefore, we do not have sufficient statistical power for a precise local RD analysis. Second, for each indicator, the state assigns scores based on discrete thresholds, and thus a RD analysis could focus on the indicators as opposed to the index score as the running variable. However, this approach would capture only response to indicators as opposed to the stress label. As discussed later in the paper, while stress labels are widely covered in the media, specific indicators are technical and may not draw as much attention.

Counties may also receive labels. Because later analysis on housing prices assigns the label of the smallest jurisdiction to each house, county labels are not applicable and thus excluded from the figure as well.

The few localities that were not reviewed did not submit financial data in compliance with state rules by the review deadline. These localities are excluded from the analysis.

Only GO bonds are included because the yield of nonGO bonds may depend not on the financial condition of issuer government but rather the creditworthiness of the debt-financed projects. Only long-term bonds with maturity longer than a year are included because short-term bond is a stress factor analyzed by the state monitoring system.

A property can be located in a county, a city or town, and a village at the same time. We assign to each property the state designation for the smallest jurisdiction the property is located in, that is, village if applicable and town or city otherwise. The rationale is that those jurisdictions are the closest to the taxpayers and may provide services most essential to them. A later robustness check also controls for labels of overlapping local governments including school districts.

Housing characteristics include the number of full bathrooms, the number of bedrooms, whether having a full basement, a fireplace, or central air conditioning, the overall physical condition and the construction grade as determined by the assessor, quadratic form of the square footage of the living area, and property age.

While time fixed effects included in the regression can control for changes in the overall market environment, the shape of the yield curve could change over time. To address this possibility, we use yield spread to a synthetic riskless bond as the dependent variable (Yang 2019).

Bond characteristics include issue size, maturity, tax and insurance status, issuing method, and credit ratings. Credit rating agencies may respond to information conveyed through the state monitoring program and adjust ratings. If that is the case, the rating variables may pose as an overcontrol. As a robustness check, results from regressions not controlling for credit ratings (not reported) are similar.

Indeed, research finds that financial intermediaries such as the credit rating agencies rely on similar financial indicator analysis to understand the creditworthiness of local government debt (Johnson et al. 2012). It is worth noting that not all municipal bonds have a credit rating, unless the issuer chooses to pay for one. In our sample, about 92 percent of the bonds carry ratings from at least one rating agency, as shown in Appendix Table 9.

First, the bond market charged borrowers with higher fund balance to expenditure ratios (indicator 2) less, as localities with more savings are better positioned against fiscal shocks and more likely to pay back debt. Second, the market charged a risk premium on borrowers with high debt service costs (indicator 9), as existing debt represents competing claims over the government’s financial resources.

Interestingly, the school district labels are not statistically significantly associated with house sale prices. While this contradicts findings from Thompson (2016) that in Ohio, school district stress labels reduce housing prices, the two states’ monitoring programs are different. Labeled school districts in Ohio must take corrective actions, and on average, cut spending and increase taxes, as Thompson (2016) shows. No such actions are required in New York. Therefore, the decline in housing prices observed in Ohio could be due to the reduction in public services, as opposed to solely an informational shock. But if school district labels in New York provide no informational shock, why would general-purpose government labels? This may be because school performance is highly correlated with school finances and homebuyers already have good access to information on school performance and finances through, for example, the state’s education department and online school rating platforms.

The finding also holds with alternative measures of fiscal variables, such as logged general fund revenue and spending, or logged total revenue and spending.

The regressions control for locality and year fixed effects as well as county-specific time trends, with standard errors clustered at the locality level.

The threshold is chosen so that the two groups of observations are similar in size and thus one should have a similar chance of detecting statistically meaningful relationships.

If the housing price decline following a significant stress label was a result of an information shock, there may be heterogeneity in the impact depending on how much access a local community has to the state monitoring information. As the media provides for an important source of such information, we estimate the heterogeneous effect of fiscal labels based on the number of daily newspapers in a county as reported by Gentzkow et al. (2011). Specifically, we add to the baseline specification interactions between fiscal label variables and number of newspapers. The coefficient estimates of the interaction terms are not statistically significant, and thus provide no support for heterogeneous information shocks based on newspaper coverage. This finding remains true if newspaper coverage is measured using the number of circulation or population weighted circulation.

References

Chan, J. L., & Rubin, M. A. (1987). The role of information in a democracy and in government operations: The public choice methodology. Research in Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting 3, no. Part B: 3–27.

Cuny, C. (2016). Voluntary disclosure incentives: Evidence from the municipal bond market. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 62(1), 87–102.

Cuny, C. (2018). When knowledge is power: Evidence from the municipal bond market. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 65(1), 109–128.

Daly, G. G. (1969). The burden of the debt and future generations in local finance. Southern Economic Journal, 36(3), 44–51.

Dollery, B. E., & Worthington, A. C. (1995). The impact of fiscal illusion on housing values: An Australian test of the debt illusion hypothesis. Public Budgeting & Finance, 15(3), 63–73.

Dollery, B. E., & Worthington, A. C. (1996). The empirical analysis of fiscal illusion. Journal of Economic Surveys, 10(3), 261–297.

Downs, A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Epple, D., & Schipper, K. (1981). Municipal pension funding: A theory and some evidence. Public Choice, 37(1), 141–178.

Figlio, D. N., & Lucas, M. E. (2004). What's in a grade? School report cards and the housing market. American Economic Review, 94(3), 591–604.

Fiva, J. H., & Kirkebøen, L. J. (2011). Information shocks and the dynamics of the housing market. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(3), 525–552.

Gayer, T., J. T. Hamilton, & Viscusi, W. P. (2002). The market value of reducing cancer risk: Hedonic housing prices with changing information. Southern Economic Journal, 69(2), 266.

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. M., & Sinkinson, M. (2011). The effect of newspaper entry and exit on electoral politics. American Economic Review, 101(7), 2980–3018.

Gerrish, E., & Spreen, T. L. (2017). Does benchmarking encourage improvement or convergence? Evaluating North Carolina’s fiscal benchmarking tool. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 27(4), 596–614.

Green, R. C., Hollifield, B., & Schürhoff, N. (2007). Financial intermediation and the costs of trading in an opaque market. Review of Financial Studies, 20(2), 275–314.

Harris, L. E., & Piwowar, M. S. (2006). Secondary trading costs in the municipal bond market. The Journal of Finance, 61(3), 1361–1397.

Heyndels, B., & Smolders, C. (1994). Fiscal illusion at the local level: Empirical evidence for the Flemish municipalities. Public Choice, 80(3–4), 325–338.

Izzo, E. (2018). “Comptroller: City in Moderate Fiscal Stress.” The Sun Community News. September 25, 2018.

Johnson, C. L., Kioko, S. N., & Hildreth, W. B. (March 2012). Government-wide financial statements and credit risk: Government-wide financial statements and credit risk. Public Budgeting & Finance, 32(1), 80–104.

Jordan, J. (2018). Andover, Canisteo Cited in Fiscal Stress Report. Wellsville Daily Reporter. September 30, 2018.

Landers, J. R., & Byrnes, P.E. (2000). Debt Illusion Among Local Taxpayers: An Empirical Investigation.In: Proceedings from the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association, vol. 93, pp. 187–194. National Tax Association, 2000.

Oates, W. (1988) On the nature and measurement of fiscal illusion: A survey. In: Brennan, G., Grewel, B. S., Groenwegen, P. (Eds.) Taxation and fiscal federalism: Essays in honour of Russell Mathews, pp 65–82. Sydney, Australia: ANU Press.

Office of New York State Comptroller. (2016). Fiscal Stress Monitoring System. New York: Albany.

Pew Charitable Trust. (2016). State Strategies to Detect Local Fiscal Distress: How States Assess and Monitor the Financial Health of Local Governments. Washington: DC.

Pope, J. C. (2008). Do seller disclosures affect property values? Buyer information and the Hedonic Model. Land Economics 84(4), 551–572.

Securities and Exchange Commission. (2004). "Report on transactions in municipal Securities." Washington, DC.

Schultz, P. (2012). The market for new issues of municipal bonds: The roles of transparency and limited access to retail investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 106(3), 492–512.

Spreen, T. L., & Cheek, C. M. (2016). Does monitoring local government fiscal conditions affect outcomes? Evidence from Michigan. Public Finance Review, 44(6), 722–745.

Stadelmann, D., & Eichenberger, R. (2014). Public debts capitalize into property prices: Empirical evidence for a new perspective on debt incidence. International Tax and Public Finance, 21(3), 498–529.

Thompson, P. N. (2016). School district and housing price responses to fiscal stress labels: Evidence from Ohio. Journal of Urban Economics, 94, 54–72.

Thompson, P. N. (May 2017). Effects of fiscal stress labels on municipal government finances, housing prices, and the quality of public services: Evidence from Ohio. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 64, 98–116.

Votsis, A., & Perrels, A. (2016). Housing prices and the public disclosure of flood risk: A difference-in-differences analysis in Finland. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 53(4), 450–471.

Yang, L. (2019). Not all state authorizations for Municipal Bankruptcy are equal: Impact of Bankruptcy Authorizations on State Primary Market Borrowing Costs. National Tax Journal, 72, 435–464.

Yang, L. (2020). Auditor or Adviser? Auditor (In) Dependence and Its Impact on Financial Management. Public Administration Review (2020) (in print).

Yinger, J. (1982). Capitalization and the theory of local public finance. Journal of Political Economy, 90(5), 917–943.

Acknowledgement

I thank participants at the 2018 DC Policy Day Conference, the DC-Area Public Finance and Budgeting Seminar, the 2019 Public Choice Society Annual Conference, and the 2019 University of Illinois Public Finance Conference for their helpful comments. All errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 4, 5, 6 and Tables 9 and 10.

Event study analyses of housing price, Limited sample. Panel 1. Before and after the first stress label. Panel 2. Before and after the first significant stress label. Notes: The sample is limited to properties within jurisdictions that are consistently observed 7 years before to 2 years after the first stress label. Coefficient estimates with 95 percent confidence interval are from regressions controlling for property characteristics, jurisdiction and month fixed effects, and county-specific time trends, with standard errors clustered at the locality level

Event Study Analyses of Bond Yields, Limited Sample. Panel 1. Before and after the first stress label. Panel 2. Before and after the first significant stress label. Notes: The sample is limited to bonds issued by jurisdictions that are consistently observed 7 years before to 2 years after the first stress label. Coefficient estimates with 95 percent confidence interval are from regressions controlling for bond characteristics, jurisdiction and month fixed effects, and county-specific time trends, with standard errors clustered at the locality level. The yield spread is measured, in percentage points, as the difference between the initial offering yield and a synthetic riskless bond

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L.(. Fiscal transparency or fiscal illusion? Housing and credit market responses to fiscal monitoring. Int Tax Public Finance 29, 1–29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-020-09654-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-020-09654-x