Introduction

The ability to negotiate internationally and across cultures has become vital for businesses (Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo, & Menke, Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019a; Ogliastri & Quintanilla, Reference Ogliastri and Quintanilla2016). However, cross-cultural negotiation entails communication difficulties and challenges (Imai & Gelfand, Reference Imai and Gelfand2010; Liu, Chua, & Stahl, Reference Liu, Chua and Stahl2010; Ramirez Marin, Olekalns, & Adair, Reference Ramirez Marin, Olekalns and Adair2019), and seems to result in lower outcomes (e.g., Brett, Gunia, & Teucher, Reference Brett, Gunia and Teucher2017). The behavioral theory of negotiations (Walton & McKersie, Reference Walton and McKersie1965), which is the most widespread theoretical framework in negotiation (Cutcher-Gershenfeld & Kochan, Reference Cutcher-Gershenfeld and Kochan2015), posits how fundamental to negotiation success is the choice between a distributive (or positional) and an integrative (or principled) negotiation strategy (Patton, Reference Patton2015). These two prototypes were originally developed in the United States and have been extensively assumed to hold their importance universally (Gelfand & Brett, Reference Gelfand and Brett2004). Cross-cultural studies in negotiation have been flourishing during the last few decades, especially research focusing on the effects of social, political, and cultural contexts on the negotiation process, strategies, and outcomes. Yet, most research on intercultural negotiations continues to tend to compare distant cultures, such as eastern versus western (e.g., Adler & Graham, Reference Adler, Graham, Brannen and Mughan2017; Zhang, Oetzel, Ting-Toomey, & Zhang, Reference Zhang, Oetzel, Ting-Toomey and Zhang2019), whereas a minority analyzes cross-cultural interactions among similar ones, such as westerners.

In contrast, we ask to what extent the prototypes of integrative and distributive negotiators usefully represent intercultural negotiation behavior in two western cultures, the USA and Italy. Italy, in particular, has been largely neglected in studies of cross-cultural negotiation despite its economic importance. Consequently, this study aims to contribute to fill a gap in the literature by answering the following research questions: are the behavioral theory of negotiations' prototypes (distributive-positional vs. integrative-principles), developed in the United States, generalizable to other western cultures of the world? And, what are the patterns of negotiation in Italy and the perception of foreigners who live and work there? By answering these questions, we would be contributing to the call by Brett, Gunia, and Teucher (Reference Brett, Gunia and Teucher2017) for more investigation of anomalies in extant research that could be explained by studying the cultural relevance of negotiation theory and consideration of new constructs for a truly global understanding of negotiations.

Our study focuses on behaviors that people from different national cultures demonstrate during negotiation processes, as reported by counterparts who have been negotiating with them. We use a sample of 214 reports on American and Italian negotiators to identify clusters of negotiation prototypes. Employing latent class analysis (LCA) (Collins & Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010), we aim to determine whether belonging to a specific country culture affects the probability of belonging to one of the negotiator clusters. To study the cultural relevance of the behavioral theory of negotiations (Walton & McKersie, Reference Walton and McKersie1965), we use eight questions directly related to the principles of negotiation suggested by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981). They propose a framework to help achieving a ‘good agreement’ and avoid getting stuck in a positional bargaining. In particular, they highlight that integrative agreements are the result of four negotiation principles. First of all, negotiators should separate the people from the issue to maintain the relationship, by understanding the other parties' interpretations and perceptions, an adequate handling of emotions, and effective communication and active listening. Second, the negotiating parties should focus on interests at stake, rather than their positions. Third, it is fundamental to generate creative options to solve the problem, from an inventive and unconstrained brainstorming initial process to a clear evaluation and refinement of promising proposals to negotiate on. Finally, the authors suggest agreeing upon and using objective criteria to resolve differences during the negotiation process. The framework and principles proposed by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981) are extremely popular and still extensively used by both practitioners and scholars, and linked to the distributive/integrative models (Patton, Reference Patton2015); therefore, we apply our variable selection based on this theoretical construct.

The analysis leads to the identification of three negotiation prototypes and country culture is a significant predictor of clusters' membership. Most North American negotiators adopt an integrative strategy, using objectivity, technical criteria, and avoiding haggling, even though they are impersonal and less oriented to explore the interests of the counterpart (‘impersonal integrative’). Italian negotiators are fairly equally spread between a distributive and an integrative negotiation prototype. The distributive one is the classical type, who conceives the negotiation as a zero–sum game and undertakes a bargaining process. The other one shows some of the typical traits of the integrative negotiation strategy, being oriented to explore interests and to create mutual value within a colleagueship process but is also expressing and dealing with emotions during the negotiation, a controversial subject of research and practice. This original ‘emotional integrative’ prototype of negotiators that we find for Italy represents one of the most interesting contribution of implementing an LCA in this context.

Theoretical background

Integrative versus distributive negotiations

Negotiations occur in situations where two or more parties with conflicting interests jointly seek a mutual agreement to reconcile their differences, rather than resorting to force or trial (e.g., Lax & Sebenius, Reference Lax and Sebenius1986). Over the years, as scholars have built a broad body of theoretical and empirical literature on negotiation – which embraces the development and validation of models and techniques for making agreements – they have defined two predominant negotiation prototypes: distributive and integrative negotiation model strategies (Cutcher-Gershenfeld & Kochan, Reference Cutcher-Gershenfeld and Kochan2015; Fisher, Ury, & Patton, Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981; Patton, Reference Patton2015; Walton & McKersie, Reference Walton and McKersie1965).

The distributive (or positional) negotiation strategy treats the negotiation process as positional bargaining, in which each party tries to maximize its share of payoffs, which are perceived as a fixed sum (Patton, Reference Patton2015; Pruitt & Rubin, Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986). Accordingly, negotiators assume they must distribute a fixed value, so one party will lose and the other will win (the so-called win–lose, zero–sum, or fixed–pie configuration). This focus on distributing value implies inefficiencies, distorts the negotiation relationship, and complicates creating value in the negotiation (Brett & Thompson, Reference Brett and Thompson2016).

In the integrative (or principled) negotiation strategy, parties explore options to increase the size of the joint gain, before focusing on the division of payoffs (Patton, Reference Patton2015; Pruitt & Rubin, Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986). This tends to solve problems jointly and to benefit all parties, as negotiators distribute the increased value by applying objective criteria (rather than haggling, as in distributive negotiation) (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981). Integrative negotiation is claimed to be superior to distributive negotiation because it gradually yields a more efficient and longer term agreement, to the benefit of all parties (Brett & Thompson, Reference Brett and Thompson2016).

Negotiation in cross-cultural contexts

The behavioral theory of negotiations was initially developed in the context of North American labor negotiations and business agreements (Walton & McKersie, Reference Walton and McKersie1965), and since then a vast research effort has been stimulated to expand the understanding of international negotiations involving individuals from different cultures. The main, common question that has been driving this research stream is whether distributive versus integrative behaviors in cross-cultural negotiations differ in important ways from those in intracultural negotiations (Adair & Brett, Reference Adair and Brett2005).

Although the theoretical models seem generally valid across cultures (Graham, Mintu, & Rodgers, Reference Graham, Mintu and Rodgers1994), numerous studies confirm that there are some substantial differences among cultural groups (Caputo, Marzi, Maley, & Silic, Reference Caputo, Marzi, Maley and Silic2019b; Ma, Lee, & Yu, Reference Ma, Lee and Yu2008). Culture profoundly affects how people think, communicate, and behave, including the types of agreements they make and the way they reach them (Brett, Reference Brett2007, Reference Brett2017; Salacuse, Reference Salacuse1999). A particularly prolific stream of research has compared negotiation processes exhibited by individuals from different countries, mainly using the United States as a benchmark and trying to explain any substantial deviation from the reference models in terms of different cultural qualities and idiosyncrasies (e.g., Adair & Brett, Reference Adair and Brett2005; Adair, Okumura, & Brett, Reference Adair, Okumura and Brett2001; Cai & Fink, Reference Cai and Fink2002; Gunia, Brett, & Gelfand, Reference Gunia, Brett and Gelfand2016; Morris & Gelfand, Reference Morris, Gelfand, Gelfand and Brett2004).

Most of these studies have used Hofstede's (Reference Hofstede2011) five-dimensional model of national cultures, the dimensions being power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and long-/short-term orientation (Adair & Brett, Reference Adair and Brett2005; Adair, Hideg, & Spence, Reference Adair, Hideg and Spence2013; Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, Reference Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson2006; Vieregge & Quick, Reference Vieregge and Quick2011). For example, individualistic cultures may be expected to be more self-centered and focused on personal gains (Brett & Okumura, Reference Brett and Okumura1998), whereas negotiators from a collectivist culture concentrate more on forming a relationship and discriminate between in-group and out-group partners, feeling strongly linked to the former and promoting their collective interests and goals during the negotiation process, an approach that can lead to higher joint profits (Cai, Wilson, & Drake, Reference Cai, Wilson and Drake2000). Caputo and colleagues (Reference Caputo, Ayoko and Amoo2018, Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019a) found that power distance and masculinity increase the preference for a distributive strategy, whereas uncertainty avoidance and collectivism increase the preference for an integrative one.

However, some scholars argue that Hofstede's original sample fails to capture how culture evolved over time and neglects within-country cultural differences (e.g., Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, Reference Kirkman, Lowe and Gibson2006). The Globe study (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004) adds cultural dimensions and points to differences between culture ‘as it is now’ and ‘as it should be.’ Hall (Reference Hall1976) identifies two important cultural characteristics: monochronic/polychronic time and communication context. Polychronicity is necessary to create value by package negotiations rather than issue by issue. The implicit communication context can be high or low. Negotiators from low-context communication cultures favor direct information sharing, whereas those from high-context communication cultures assume that some meanings and nuances must be inferred (Adair et al., Reference Adair, Brett, Lempereur, Okumura, Shikhirev, Tinsley and Lytle2004).

A recent stream of research focuses on the distinction among dignity, honor, and face cultures (Aslani et al., Reference Aslani, Ramirez-Marin, Brett, Yao, Semnani-Azad, Zhang and Adair2016; Brett & Thompson, Reference Brett and Thompson2016; Leung & Cohen, Reference Leung and Cohen2011). Other studies have highlighted other aspects that can impact the outcomes of negotiation, including emotions (Gelfand & Brett, Reference Gelfand and Brett2004; Ogliastri & Quintanilla, Reference Ogliastri and Quintanilla2016; Schlegel, Mehu, van Peer, & Scherer, Reference Schlegel, Mehu, van Peer and Scherer2018), consensus building and trust (Brett, Gunia, & Teucher, Reference Brett, Gunia and Teucher2017; Liu, Friedman, Barry, Gelfand, & Zhang, Reference Liu, Friedman, Barry, Gelfand and Zhang2012; Yao, Zhang, & Brett, Reference Yao, Zhang and Brett2017), cognitive biases (Caputo, Reference Caputo2013, Reference Caputo2016; Morris & Gelfand, Reference Morris, Gelfand, Gelfand and Brett2004), and cultural intelligence (Caputo, Ayoko, & Amoo, Reference Caputo, Ayoko and Amoo2018; Caputo et al., Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019a; Groves, Feyerherm, & Gu, Reference Groves, Feyerherm and Gu2015; Imai & Gelfand, Reference Imai and Gelfand2010).

Cultural differences among international negotiators can represent a serious obstacle to effective negotiation (Adler & Aycan, Reference Adler and Aycan2018; Graham, Mintu, & Rodgers, Reference Graham, Mintu and Rodgers1994; Salacuse, Reference Salacuse1999), as they potentially affect the role of the negotiators, the nature of communication, mutual perceptions, preferences, and the negotiation style itself, finally determining the outcome and form of the agreement (Cai, Wilson, & Drake, Reference Cai, Wilson and Drake2000; Gelfand & Brett, Reference Gelfand and Brett2004; Gelfand, Brett, Gunia, Imai, Huang, & Hsu, Reference Gelfand, Brett, Gunia, Imai, Huang and Hsu2013; Usunier, Reference Usunier2018). Nevertheless, negotiators from different cultures will not always clash and reach suboptimal agreements; indeed, differences may offer opportunities. Adler (Reference Adler1980), who refers to this as the ‘culturally synergistic’ approach, claims that international negotiators can generate mutually beneficial options by identifying interests that different parties value differently. In other words, in cross-cultural negotiations, the process complexity increases, but the opportunities of reaching an agreement with joint gains also improve when negotiators recognize their fundamental compatibilities instead of focusing on stereotypes.

In sum, there is still a need to clarify how distinctive cultural traits affect negotiation processes and outcomes: to move from qualitative descriptions and manuals of ‘dos and don'ts’ toward a more comprehensive and profound examination of the influence of culture on negotiators' tactics, outcomes, motives, and cognitions, along with a deeper understanding of the broad effects of intercultural interaction (Adler & Aycan, Reference Adler and Aycan2018). To this end, we formulate two main propositions for research:

Proposition 1: The integrative and distributive negotiation prototypes should be valid in both Italy and the USA.

Proposition 2: The negotiation prototypes in Italy and the USA should differ.

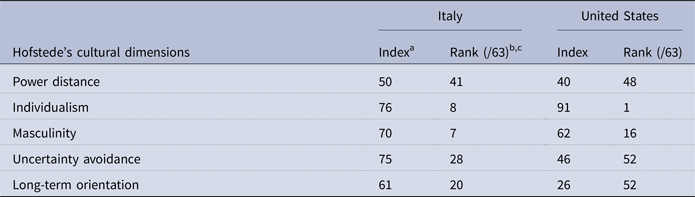

We aim to determine whether the distributive and integrative negotiator prototypes can be validated within two distinct Western cultural clusters: the Latin European and the Anglo (see, e.g., House et al., Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2004). Indeed, the characterization of Italy and the United States along the cultural dimensions proposed by Hofstede (Reference Hofstede2001) suggests that although they share some cultural traits (e.g., they are both classified in middle-to-low positions for power distance and relatively high for masculinity), the North American country exhibits the highest position on individualism and Italy presents stronger traits in terms of uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation.Footnote 1 These divergencies can have a significant effect on negotiation strategies. With our analysis, we also contribute to the study of Italy, a major world economic player,Footnote 2 which is rarely mentioned in studies on cross-cultural negotiations.

Methods

Research design and data collection

We sought a method that would allow us to investigate real negotiations and isolate focal constructs, and would not be influenced by previous respondent behaviors (Caputo, Reference Caputo2016; Ogliastri & Quintanilla, Reference Ogliastri and Quintanilla2016). We therefore adopted a mixed methods approach (Hesse-Biber, Reference Hesse-Biber2010), triangulating the results of LCA (Collins & Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010) with the testimonies about experiences of direct negotiations in different business contexts (Ogliastri & Quintanilla, Reference Ogliastri and Quintanilla2016).

We adopted a previously validated questionnaire made of 20 open-ended questionsFootnote 3 (see, for further explanation, Ogliastri & Quintanilla, Reference Ogliastri and Quintanilla2016). The answers were coded into 53 categorical variables in order to make the data easily intelligible in mostly Yes/No/Don't know answers. An example of the codebook is presented in Appendix 3. This is a quantitative data set, with face validity and conveniently structured for statistical analysis. We gathered the data within the framework of theory of practice (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1977), using experiences to develop theory (Broome, Reference Broome2017) and integrating teaching, practice, theory, and research (Ebner & Parlamis, Reference Ebner and Parlamis2017). To reduce the risk that results might be biased by specific contextual events, data were collected between 2010 and 2018. Our database consists of thorough records of intercultural negotiation experiences and includes 214 observations, from foreign experienced managers, about American (N = 80) and about Italian (N = 134) negotiators.

Lewicki, Saunders, and Barry (Reference Lewicki, Saunders and Barry2020) report how one of the main limitations of the vast body of research in negotiation consist of result being drawn from laboratory experimental design rather than accounts of real negotiations. Therefore, answering to this call for a closer to reality approach in negotiation research, we employed a convenience sampling technique gathering data from interviews with experienced managers. The interviews were carried out by international students in an MBA negotiation course as part of their assignment. To avoid the risks associated with self-reported measures, each MBA student conducted an interview with a foreign manager (i.e., expat), who reported the most common or normal behavior of his counterparts in the country of origin of the student. By applying this method we reduced the interviewer biases present in normal qualitative research, as a different interviewer was employed for each interviewee. In addition, we limited the research bias as we, the researchers, were not directly involved in the interview, therefore separating the cognitive processes of data collection, interpretation, and analysis. Moreover, our method guaranteed that the accounts were provided by counterparts not sharing the same cultural background, ensuring a better report of cross-cultural interactions. That meant that the managers that explained their negotiation experiences in Italy (or in the USA) were from different backgrounds and nationalities, helping to further reduce possible biased interpretations of results.

We then developed a codebook, comprising 53 variables, to convert the qualitative information from the interviews into quantitative data.Footnote 4 To further limit the researcher bias, five graduate research assistants were employed over 5 years with the task to code interviews, with an interrater reliability coefficient (Fleiss' kappa) of .65, implying ‘substantial agreement’ in the coding phase.

In addition, as a preliminary analysis showed interesting results about the Italian negotiators that begged further analysis due to the lack of research about Italian negotiators, we complemented the study with 86 qualitative interviews based on a different questionnaireFootnote 5 and focusing on the specific negotiation experience of a foreigner with an Italian counterpart. In line with Nielsen et al. (Reference Nielsen, Welch, Chidlow, Miller, Aguzzoli, Gardner and Pegoraro2020) recommendations, the responses were classified, and relevant quotations were used to triangulate and deepen our theoretical understanding and interpretation of the quantitative results.

Data analysis

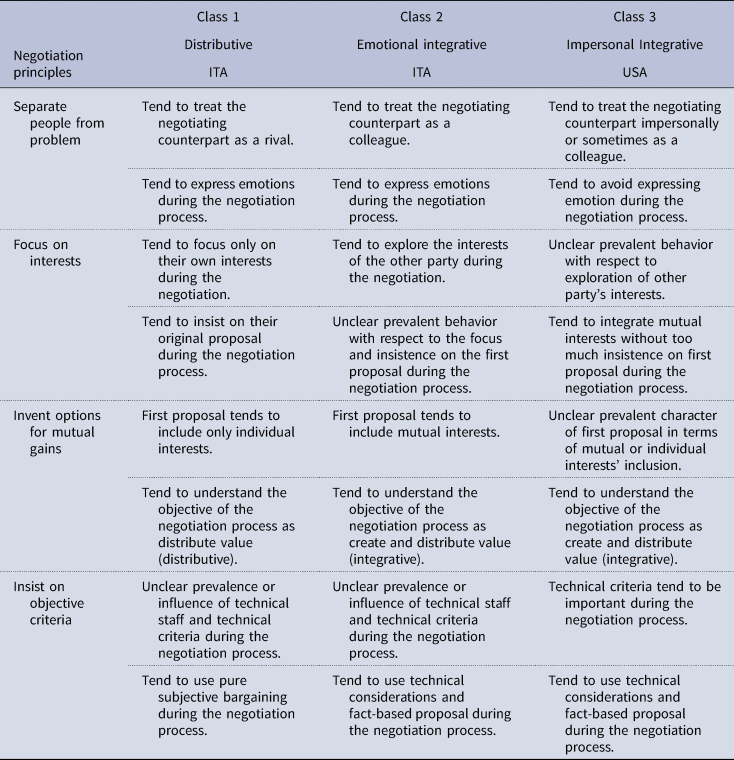

The sample size of the quantitative database (214 observations and 53 variables) immediately ruled out the possibility of using the whole set of variables to perform any statistical analysis. Therefore, we initially needed to reduce the variables to a subset that we could use to identify meaningful clusters of respondents. Basing our selection on theoretical grounds, we chose eight variables that best described the four negotiation principles proposed by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981): separate people from the problem, focus on interest (not positions), invent options for mutual gain, and insist on objective criteria (see Table 1).

Table 1. Variable selection according to principles of negotiation (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981)

According to the theoretical framework developed by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981), the negotiator that seeks integrative agreements while maintaining the relationship with the counterpart should not treat the other party as rival, not let his/her emotions to dominate the process, try to explore and understand the expectations of the other party, not focusing excessively on the first proposal, but rather integrating mutual interests to reach a satisfactory agreement for both parties. Moreover, they suggest that the negotiation process should be based on creating value first, and then use objective considerations and technical criteria to distribute the value.

We then applied latent class analysis (hereafter LCA), a special case within the more general class of latent variable models (Bartholomew, Knott, & Moustaki, Reference Bartholomew, Knott and Moustaki2011). The most distinctive feature of these models is that researchers cannot directly observe some of their variables, either because the variables are difficult or impossible to measure, or simply because the researchers did not measure them. These latent variables, nonetheless, form a critical part of the model and strongly influence the behavior of individuals. Although this set of variables cannot be observed, the researcher does have access to another set of observed, manifest variables that potentially correlate with the latent variables (Goodman, Reference Goodman1974).

In LCA, the latent variable is categorical, comprising a set of latent classes with multinomial distribution, which are measured by observed indicators. The overall objective of performing LCA on a set of variables is to derive a batch of latent classes (or ‘clusters’) that represents the response pattern in the data and gives a sense of the prevalence of each latent class (Collins & Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010).

Following Collins and Lanza (Reference Collins and Lanza2010), we assume the existence of a latent categorical variable g that can take on G possible values:

These values themselves neither have a special meaning nor represent an ordinal scale; they are just labels. In our case, they are associated with different negotiation behaviors.

We cannot observe g directly, but we have access to the manifest categorical variables j = 1, …, J – (in our case, the answers to the questions in the survey about cross-cultural negotiation). Each categorical variable j has k j = 1, …, K j response categories.Footnote 6

We define x = (k 1, …, k j) as a complete response pattern, namely a vector of responses to the J manifest categorical variables. Let x j represent element j of a response pattern x.

On the assumption that the manifest variables are mutually independent of each other, and conditional on being a member of group g, the probability density of an observed response pattern x can be written as:

$$x\vert g\sim \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } , \;$$

$$x\vert g\sim \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } , \;$$where 1(x j = k j) represents an indicator variable that equals 1 when the response to variable j is the kj-th possible answer, and 0 otherwise. ![]() $P_{j, k_j\vert g}$ represents the probability that the categorical variable takes on the kj-th value and acts as the probability for each possible response. The index g explicitly refers to the fact that these probabilities differ among the latent classes.

$P_{j, k_j\vert g}$ represents the probability that the categorical variable takes on the kj-th value and acts as the probability for each possible response. The index g explicitly refers to the fact that these probabilities differ among the latent classes.

One fundamental assumption of latent class models is the local independence assumption, which implies, conditionally on the latent variables, that the observed variables are independent.Footnote 7 This assumption makes LCA a relatively simple model to estimate. If membership in the different groups acts as another random variable, then the full joint probability distribution is defined as:

$$x\sim \sum\limits_{g = 1}^G {\pi _g} \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } , \;$$

$$x\sim \sum\limits_{g = 1}^G {\pi _g} \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } , \;$$where π g represents the probability of belonging to class g, the so-called mixing proportion from cluster analysis.

Maximum likelihood (ML) estimates the parameters of the model based on the data and results in two outputs:

• Latent class prevalences: The π g values represent the probabilities of membership in the different classes. They measure the importance or prevalence of the different clusters in the population.Footnote 8

• Item-response probabilities: The

$P_{j, k_j\vert g}$ values are calculated for each group and for each question in the survey and express the relation between each observed variable and each latent class. They represent a vector of probabilities that measures the probability of a specific pattern of answers to the different questions. The different responses allow for the different classes to be profiled.Footnote 9

$P_{j, k_j\vert g}$ values are calculated for each group and for each question in the survey and express the relation between each observed variable and each latent class. They represent a vector of probabilities that measures the probability of a specific pattern of answers to the different questions. The different responses allow for the different classes to be profiled.Footnote 9

All the formulas written above remain conditional on knowing the number of latent classes. In practice, of course, the number of classes remains unknown in advance, and one must proceed by fitting models with different numbers of classes, starting with a model with no cluster structure whatsoever (a model in which the number of classes equals 1). Then the researcher must try more complicated models, with two or more classes. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) selects the best model as a transformation (a penalized version) of the log-likelihood statistic and is generally the most appropriate goodness-of-fit criterion for basic latent class models (Collins & Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010; Linzer & Lewis, Reference Linzer and Lewis2011), as it allows picking a model that fits the data well, while remaining parsimonious and protecting against overfitting the dataset:

where LL represents the log-likelihood statistic, M represents the number of parameters in the model, and N represents the sample size. The best model is the one that achieves the smallest BIC value.

As we are interested in whether country culture predicts membership in the latent classes, we introduce a covariate Country = {1, 2} = {ITA, USA} into the latent class model. Covariates can be incorporated into LCA using a logistic regression approach (Collins & Lanza, Reference Collins and Lanza2010). The framework is the same as previously described. In addition, we introduce a covariate V, to be used to predict latent class membership. Then the latent class model can be expressed as follows:

$$x\vert v\sim \sum\limits_{g = 1}^G {\pi _g( v) } \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } $$

$$x\vert v\sim \sum\limits_{g = 1}^G {\pi _g( v) } \prod\limits_{\,j = 1}^J { \times \prod\limits_{k_j = 1}^{K_j} {P_{\,j, k_j\vert g}^{1( x_j = k_j) } } } $$where π g(v) is a standard baseline-category multinomial logistic model. In LCA with covariates, the item-response probabilities are still estimated; latent class prevalences can be easily calculated from the estimated parameters.Footnote 10

Results

The first step of LCA is to define the optimal number of clusters. Table 2 reports the fit statistics for this clustering process, comparing potential candidate models with one to four clusters. The table reports likelihood statistics, BICs, numbers of parameters, and residual degrees of freedom. In our case, the model with three classes has the smallest BIC value and therefore represents the best description of the data.

Table 2. Model selection with 1, 2, 3, or 4 clusters

a This is the preferred model according to the BIC criterion (lowest BIC).

Table 3 shows the results of estimating the LCA model with country as covariate (Linzer & Lewis, Reference Linzer and Lewis2011), which identify three distinct classes of negotiation prototypes.

Table 3. Parameter estimates for 3-class model using Country as covariate

a Conditional probabilities >.50 in bold, to facilitate interpretation.

Negotiators who fall under Class 1 (33.45% of observations) tend to practice distributive negotiation: 55% of them consider the counterpart in negotiation as a rival, and they seem to concentrate only on their own interests, neither trying to understand and fulfill the expectations of the other party (80%) nor including mutual interests in their first proposal (68%). In 81% of the cases, they are perceived as understanding the process of negotiation as a distributive, zero–sum game. On the other hand, negotiators who fit into Class 2 (29.59% of observations) and Class 3 (36.96%) tend to practice integrative negotiation. They extensively use objective criteria and technical considerations to justify their offers (80% for Class 2 and 90% for Class 3), and their counterparts largely recognize that they understand negotiation as an interest-based process to create and distribute value for mutual gains (76 and 54% for Classes 2 and 3, respectively).

Interestingly, although the overall frequencies of each class seem rather uniformly distributed, as soon as we consider the effect of the variable Country, the picture changes significantly. An Italian negotiator has a 51.17% probability of belonging to Class 1 and a 43.42% probability of belonging to Class 2, whereas an American negotiator has an 89.81% probability of fitting into Class 3. This pattern is mirrored when we consider each class separately: for Classes 1 and 2, the probability of a member's being Italian is above 90%, and for Class 3, the probability of a member's being American is also around 90%. Clearly, the variable Country has a significant impact on clustering, and the two cultural groups differ in negotiation styles and strategies.

On these grounds, we can reckon that Proposition 1 is partially supported by our data, as we identify both the distributive and the integrative negotiation prototypes for Italy, but only the integrative one for the USA – a finding that has precedents in the literature (e.g., Pruitt, Reference Pruitt1981).Footnote 11 The fact that both Classes 2 and 3 tend toward integrative negotiation but are separate clusters with distinctly national membership patterns indicates that negotiation prototypes are not completely homogeneous across different cultures, in accordance with Proposition 2.

It is important to notice here that, despite sharing a common history, religion, ancestry, and language, Italy is not totally homogeneous, with differences in values, attitudes, and behaviors between North and South (see, e.g., Clò, Reference Clò2006). In his online platform, which allows users to compare and contrast the cultural characteristics of countries, Hofstede recognizes this differenceFootnote 12 (in particular, on the dimensions of power distance and individualism), which makes Northern Italy more similar to the USA. Our databases do not include information on the regional origin of the Italian counterparts with whom our respondents negotiated, so we adopt Hofstede's general list of Italian cultural features. And indeed, both Classes 1 and 2 present intriguing idiosyncrasies that substantially differentiate them from the predominantly North American Class 3.

First, negotiators of both Classes 1 and 2 are reported to express emotions during the negotiation process (75 and 60%, respectively). Given that these two classes are mainly composed of Italian individuals, this result suggests that emotionality is an embedded cultural characteristic that persists in negotiation, whichever strategy is used. In their review of negotiation behaviors linked to peculiar cultural traits, Hofstede et al. (2012) state that negotiators from uncertainty avoiding cultures tend to have an emotional style of negotiation and it is important for them to make sure that their counterpart understand and are aware of their feelings (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). The extensive expression of emotions during the negotiation process displayed by Italians can be a reflection of their relatively high uncertainty avoidance culture (Italy ranks 28 out of 63 countries on this dimension of the Hofstede's model, whereas the USA ranks 52Footnote 13).

The topic of emotions is also often mentioned in our qualitative database. For instance, a Colombian director of a legal office who has an Italian woman client in Bogotá commented that ‘[Italians] are very expressive … they laugh or cry or scream when they feel it and express everything they think and feel without fears’ (Interview 18). Emotions seem to have an ambiguous impact on the negotiation process, as they can manifest sometimes as kindness and friendship and sometimes as aggressiveness and lack of control. A Mexican interviewee reported, ‘[Italians] are very expressive, their gestural and body language is very evident; when they discuss, the situation can turn tense due to the volume of their voice and the intention of the message … Their intense emotions are culturally natural; their “openness” can degenerate into hostility but also [can manifest] in an affectionate, sympathetic, or even “convincing” gesture’ (Interview 86). This trait is commonly recognized by Italians themselves. An Italian owner of a restaurant in Spain, for example, stated that ‘The Italians and Spaniards have a very similar character, we are visceral, impulsive …’ (Interview 42).

In general, this type of emotional negotiator perceives negotiation meetings as an occasion for social contact; participants tend to discuss generalities, and technicians seldom participate in the process. In our data, for both Classes 1 and 2, negotiating counterparts seem unsure whether or not technicians are involved in the negotiation process (58 and 48%, respectively).

It is also not very clear whether negotiators in Classes 1 and 2 essentially perceive the negotiation as a bargaining process. On the one hand, in Class 1, 60% of individuals seem to base their strategy on haggling, whereas in the rest of the cases it is hard for the counterpart to assess this attitude. On the other hand, in Class 2, negotiators are almost equally distributed, with 37% of them insisting on their initial proposal and showing a bargaining attitude, and 39% of them trying to integrate mutual interests into the negotiation and pursuing the creation of shared value. This lack of clarity is reflected also in our qualitative database. A Colombian sales manager stated that ‘with them [Italians] there is not much bargaining possibility’ but also that Italians ‘are flexible to the extent possible, friendly, open, and avoid conflict and problems’ (Interview 5). Another Colombian interviewee, who oversaw sales coordination with Mediterranean Europe, commented regarding negotiating with Italian counterparts: ‘Sometimes there was haggling, but in general terms it was a very well-structured process, […]. Basically, intermediate points between the two positions were achieved, [and] new clauses were drafted, taking the obligations of both parties to logical points, seeking that the agreement and the cooperation of the companies really occurred without damages to any of them’ (Interview 19). The apparent coexistence of distributive and integrative strategies among Italian negotiators may explain this ambivalence. In contrast, the direct assessment of how the counterpart understands and handles the negotiation process differentiates the two styles explicitly: 81% of individuals in Class 1 are perceived as distributive and 76% of those in Class 2 are recognized as integrative.

The North American cluster shows predominantly integrative attitudes, even if some of the behaviors are distributive. In particular, 44% of individuals in Class 3 are perceived to treat the counterpart impersonally and only 26% as a colleague. Moreover, for the negotiation counterparts it seems to be difficult to assess whether Americans try to explore, understand, and fulfill the expectations of the other party during the negotiation process (48% say yes and 42% no) and whether they incorporate mutual interests at the beginning of the negotiation (44% are not sure). When asked directly to assess how the US counterparts understand the negotiation process, 54% of the respondents perceive them as integrative and problem-solving, whereas 40% interpret them as merely interested in distributing value.

The United States are ranked as the most individualistic country according to the Hofstede's framework and these ambiguous results can be a manifestation of this cultural trait. In fact, Hofstede et al. (2012) state that negotiators from highly individualistic societies tend to conduct the process having clear in mind their own personal interests (whatever those interests are), whereas they might pose less emphasis on relationship building (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001). This trait could make the negotiating counterpart doubt whether his/her interests and perspectives are indeed taken into consideration by the US negotiators.

In summary, our first cluster identified through LCA clearly represents distributive negotiators, whereas the second and third clusters represent integrative negotiators (Table 4). The distributive negotiator is the classical type, who does not apply the negotiation principles proposed by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981). This negotiator conceives negotiation as a zero–sum game and the counterpart as a rival to defeat, does not explore the interests of the other party to make integrative, mutually beneficial offers, induces a process of bargaining and haggling (instead of using objective criteria to distribute value), and uses emotions during the negotiation process. The second cluster represents a new type of integrative negotiator found in Italy. This negotiator seems to treat the counterpart as a colleague (rather than as a rival or impersonally), explores interests before making a proposal for mutual benefits, is strongly oriented to mutual value creation, expresses emotions, and uses objective criteria, even though he or she may end up bargaining if the situation evolves in such a way. The third type of negotiator (mainly American) also displays integrative behaviors, applying objective and technical criteria and avoiding haggling, but is less oriented toward exploring the interests of the other side, is impersonal, and avoids expressing emotions.

Table 4. Summary of research findings

On the one hand, our analysis confirms that US individuals tend to take an integrative approach to negotiation (e.g., Brett, Adair, Lempereur, Okumura, Shikhirev, and Tinsley, Reference Brett, Adair, Lempereur, Okumura, Shikhirev and Tinsley1998). The American culture is characterized by fairly low power distance and medium uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), high individualism and results orientation (Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, Dastmalchian, & House, Reference Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, Dastmalchian and House2012), and low-context communication and monochronicity (Hall, Reference Hall1976), in spite of the efficiency of a multitask polychronic process (Brett et al., Reference Brett, Adair, Lempereur, Okumura, Shikhirev and Tinsley1998). American negotiators are said to feel relatively entitled to make proposals during the process, to be eager to explore trade-offs and alternatives, and to avoid ‘leaving money on the table.’ Such behaviors can help build options for mutual gains. However, our results also highlight some distributive features of US negotiators, suggesting that US negotiation strategy requires more specific analysis.

On the other hand, the Italian culture scores in the middle zone in power distance and high in uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), suggesting a certain formality in negotiations, in both role definition and detailed planning. High uncertainty avoidance is also related to the emotional style of negotiation highlighted in the analysis for Italian individuals, regardless of the negotiation strategy adopted. Italian society is also characterized by high masculinity (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), which entails a certain propensity toward competition that manifests in distributive negotiation and is necessary to obtain better economic results in the second stage of the integrative strategy.

Discussion

Our results confirm the general validity of the distributive/integrative negotiation framework (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981; Walton & McKersie, Reference Walton and McKersie1965). It is in line with earlier and recent studies that supported this theoretical model even for multicultural contexts (e.g., Graham, Mintu, & Rodgers, Reference Graham, Mintu and Rodgers1994). Nevertheless, similar to previous researchers, we also find some peculiarities related to different cultural backgrounds (Caputo et al., Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019a; Metcalf, Bird, Shankarmahesh, Aycan, Larimo, & Valdelamar, Reference Metcalf, Bird, Shankarmahesh, Aycan, Larimo and Valdelamar2006). In particular, we identify some nuances for the integrative negotiation paradigm that seem to be related to cultural traits in the context of international negotiations. This opens space for a better understanding of the complexities related to intercultural negotiations, even for Western countries that are not considered so culturally distant, such as the United States and Italy.

From the analysis, it clearly emerges that Italian people are in general very passionate and it is culturally acceptable to express emotions; indeed, not doing so is considered dishonest or disingenuous, and the attempt to be detached is perceived as a form of deception. This cultural value leads to an extensive use of varying voice tones and body language: Italians are used to high-context communication (Hall, Reference Hall1976).

Our finding of both types of negotiators in Italy aligns with the picture presented by Cominelli and Lucchiari (Reference Cominelli and Lucchiari2017) and Caputo and Valenza (Reference Caputo, Valenza, Euwema, Medina, Garcia and Pender2019), who identify a continuum that ranges from ‘Competing’ (a conflict management style that implies a win–lose perspective) to ‘Collaborating’ (a view of conflicts as problems to be solved jointly, which means searching for a win–win solution). This divide in the Italian results on negotiation styles could mirror Italy's strong cultural differentiation between North and South (Clò, Reference Clò2006) – a possibility that could be further examined by comparing data that include negotiators' regional provenance (Kaasa, Vadi, & Varblane, Reference Kaasa, Vadi and Varblane2014).

Our results further shed light on a substantive difference between Italian and American negotiators. Indeed, one of our interviewees pointed out this feature straightforwardly: ‘The Italian is undoubtedly a kind person to negotiate with, but absolutely different from the American type, for example, which is faster, more practical in the negotiation. With them [Italians] there are a few more steps … The negotiation and the challenge are a little more sentimental’ (Interview 17). These results allow us to reject the hypothesis of homogeneity in negotiation strategies and styles across different cultural clusters, even within Western culture.Footnote 14

In addition, in what could be another management lesson from Italy, the main finding of our analysis seems to yield a new ‘emotional integrative’ negotiator prototype, one that merges integrative and emotional features. Posthuma (Reference Posthuma2012) posits that we need research on emotions – not just cognitions and behaviors – to understand and facilitate effective negotiations, and the use of emotions may be positive from a managerial perspective (Gunkel, Schlaegel, & Taras, Reference Gunkel, Schlaegel and Taras2016; Kopelman & Rosette, Reference Kopelman and Rosette2008). In a meta-analysis, Sharma, Bottom, and Elfenbein find that individuals with strong emotional intelligence ‘achieve lower economic outcomes, but higher psychological subjective value’ (Reference Sharma, Bottom and Elfenbein2013: 311). Emotional intelligence is an important social skill for life, but it does not produce higher economic results for a negotiator unless both counterparts demonstrate a certain ability to handle and identify emotions (Der Foo et al., Reference Der Foo, Elfenbein, Hoon Tan, Chuan Aik, Maw, Elfenbein and Chuan Aik2004). The pending question is the relative economic benefit of dealing with emotions in negotiations, especially distinguishing between positive and negative ones (e.g., Luomala et al., Reference Luomala, Kumar, Singh and Jaakkola2015; Wong, Reference Wong2020).

Recently, in discussing how to measure dignity, face, and honor cultures, Yao, Ramirez-Marin, Brett, Aslani, and Semnani-Azad (Reference Yao, Ramirez-Marin, Brett, Aslani and Semnani-Azad2017) included the use of emotions in negotiations as an indicator of distributive negotiation culture. Our results, however, imply that is not necessarily the case, as the new type of Italian integrative negotiator makes all the moves to increase mutual value (a key principle), but also handles emotions in a constructive way. These findings contribute to the debate over whether Latin Europe is indeed a ‘dignity’ culture (Fosse, Ogliastri, & Rendon, Reference Fosse, Ogliastri and Rendon2017; Ogliastri, Rendón, & Fosse, Reference Ogliastri, Rendón and Fosse2017); our analysis suggests that Italy does not share negotiation prototypes with the US dignity culture, and confirms Harinck, Shafa, Ellemers, and Beersma's (Reference Harinck, Shafa, Ellemers and Beersma2013) finding that cooperative negotiation behaviors exist in honor cultures. However, our dataset does not include key details, so this remains an interesting topic for future research.

Furthermore, it is still necessary to ascertain the specific behaviors of this ‘emotional integrative’ negotiator prototype, as well as the outcomes the negotiator gets from the negotiation process and the relative effects of different types of emotions (Wong, Reference Wong2020). This negotiator should also be distinguished from the ‘soft’ distributive negotiator prototype described by Fischer, Ury and Patton (Reference Fisher, Ury and Patton1981). Students often confuse the soft negotiator with the integrative one, but their strategies are different: the soft negotiator is likeable, shows concern for the needs of the counterpart, and is willing to make sacrifices in order to get to a quick agreement, but he or she does not believe that it is possible to increase value and conceives negotiation as a distributive zero–sum game. It is crucial to find out whether the distinctive Italian ‘emotional integrative’ negotiation strategy leads to better outcomes: even though this prototype is clearly different from the soft one, is it competitive enough to succeed at getting a large piece of the jointly increased value?

More research is also needed to compare and contrast this new ‘emotional integrative’ negotiation prototype with the ‘impersonal integrative’ one (Harinck et al., Reference Harinck, Shafa, Ellemers and Beersma2013). Indeed, as a further development of this study, it would be of great interest to extend the analysis, first by including more countries of the Latin Europe and Anglo cultural clusters, and second by broadening the database to all the relevant cultural clusters validated by Gupta, Hanges, and Dorfman (Reference Gupta, Hanges and Dorfman2002). An enlarged study would surely lead to more robust results, allow for wider cross-cultural comparison, and support a deeper understanding of the key cultural features that bring about different attitudes, strategies, reactions, and final outcomes during the negotiation process. Moreover, it would be of great interest to incorporate interactions of negotiators from specific cultural backgrounds to study the effects on the outcomes (Cai, Wilson, & Drake, Reference Cai, Wilson and Drake2000; Fosse, Ogliastri, & Rendon, Reference Fosse, Ogliastri and Rendon2017). Starting from our findings, these extensions could give managers in multicultural environments a more comprehensive map of the complex world of cross-cultural negotiation and maximize the chances to reach agreements for joint gains.

Conclusion

The contributions of this study are manyfold. First, we have contributed to the cross-cultural negotiation and international management literature by complementing the global picture of cross-cultural negotiation differences by introducing one of the first analysis of Italian negotiators. Second, we have contributed to the cross-cultural negotiation literature by deepening our understanding of the role of culture in the selection of a negotiation strategy, as our results clearly shows how negotiators from Italy and the USA tends to choose a different style. Such results gave also light to a third, and probably most important, contribution to the field of study of cross-cultural negotiation, by unveiling a third negotiation prototype that we called ‘emotional integrative.’ Our findings are relevant as they seem to give insight into a multifaceted nature of the original distributive versus integrative framework, where the differential importance given to emotions in certain cultures (such as the Italian vs. the American) allows for a development of a specific, nontypical, negotiation prototype, especially among integrative negotiators. This result is in line with a trend to understand relationality in cross-cultural negotiations (Cheng, Huang, & Su, Reference Cheng, Huang and Su2017; Graham, Reference Graham2019; Usunier, Reference Usunier2018).

Even though the results and contributions of this study are interesting and, in parts, counterintuitive, a number of limitations requiring future research are present. First, our results are drawn by the accounts of past experiences of negotiating with Italian and American negotiators, and as such are unavoidably subject to perceptions and the bias of recall (Fischhoff & Beyth, Reference Fischhoff and Beyth1975). Furthermore, qualitative data collections and analyses are intrinsically affected by subjectivity, which we tried to limit by having a cross-cultural approach and adopting a diverse and large pool of informants and interviewers (Fosse, Ogliastri, & Rendon, Reference Fosse, Ogliastri and Rendon2017). These issues are very common in negotiation research (Lewicki, Saunders, & Barry, Reference Lewicki, Saunders and Barry2020), and we call for future studies to continue in methodological advancements that allow for better proxies of real negotiations. Second, our study focused on comparing only two countries (USA and Italy) and did not investigate how the negotiators' prototypes would relate to each other. Future research could address this gap by extending our research in investigating the interaction dynamics of the identified prototypes, as well as looking at more countries and cultures. Finally, similarly to Fosse, Ogliastri, and Rendon (Reference Fosse, Ogliastri and Rendon2017) we should be careful in labeling the typical ‘Italian’ or ‘American’ as both countries have had demographic and social changes over the years that have shaped culture and negotiation style. Future research avenues could focus on a truer account of cultural diversity, for example by looking directly at individual cultural values (Caputo et al., Reference Caputo, Ayoko, Amoo and Menke2019a).

Our contributions are also of practical and managerial relevance (summarized in Table 4). Our findings suggest that managers and negotiators interacting with Italian negotiators need to pay particular attention to the role played by emotions when aiming to achieve integrative agreements. Similarly, when negotiating with American negotiators, to achieve integrative agreements the focus seems to be more toward the impersonal and technical considerations of the negotiation. Finally, according to our results, training is implicated. Negotiators and managers who would like to successfully bridge across cultures and within global environments will benefit from training that is culturally focused. Indeed, training negotiators almost exclusively on American-based content, may displace efforts to successfully reach integrative agreements with other cultures, as the Italian experiences have shown. Conflict management and negotiation training packages should not only train negotiation skills, but also emotional and cultural competencies to effectively negotiate.

Appendix 1: Hofstede's cultural dimensions: Italy versus United States

Appendix 2: Intercultural negotiation: Questions about 20 topics

(1) Negotiation culture: Summing up: how do they negotiate?

(2) Perception of the other party: Do they conceive the counterpart as a friend, a colleague, a rival, or neutrally impersonal?

(3) Time perspective: Are they long-term or short-term oriented?

(4) Trust base: Is trust based on the person, on the legal system and the written contract, or on previous experience?

(5) Risk taking: Do they take risks of not delivering commitments?

(6) Who are the negotiators: What criteria do they use to select negotiators?

(7) Decision making: How do they decide and who makes decisions?

(8) Formality: Are they informal/formal, do they follow a protocol, how close is interpersonal treatment?

(9) Informal negotiations: Do they use out-of-the-office negotiations?

(10) Prenegotiations (and negotiation preparation): Do they have previous meetings? Do they come prepared?

(11) Opening: Do they open with extreme offers, use objective criteria to justify offers, haggling?

(12) Arguments: Do they use persuasion, emotionally moving language, hard data, threats, rational debate?

(13) Emotionality: Do they induce a rational or emotional process, expressive or instrumental use of feelings?

(14) Power tactics: Threats, intimidation, fake lack of interest, aggressiveness, confrontation?

(15) Discussion level: Do they discuss details or generalities?

(16) Time during negotiation: Are they punctual, polychronic, slow, agenda focused?

(17) Type of agreement: Oral, in writing, legal, official agreements?

(18) Commitment and fulfillment: Are agreements binding?

(19) Perception flexibility: Are they rigid or flexible about changes?

(20) Ways of expression: Interpersonally friendly, courteous, confrontational, diplomatic, imposing, evasive, neutral?

Appendix 3: Sample of the codebook

(1) Emotionality: Do they induce a rational or emotional process, expressive or instrumental use of feelings?

Questions: How much room is left for expressing emotions during the negotiation, or is it a neutral and objective process? Is there room for personal expression needs or is it an instrumental technique meant to influence the other party? Are hostility and affection displayed by only one of the parties or by neither of the two?

Codebook:

-

Do they express emotions in negotiations?

-

___Yes (emotional)

-

___No (neutral, objective, rational, formality)

-

___Not sure, no information, I don't know

-

Expressive nature of feelings expressed in negotiations?

-

___Yes (ventilating feelings is acceptable for them, expressive culture)

-

___No (it is not accepted, not considered professional or mature)

-

___Not sure, no information, I don't know

-

Instrumental nature of feelings expressed in negotiations?

-

___Yes (feelings are a tool to impress, a negotiation tactic, impact oriented)

-

___No (they are not used, or considered hypocrisy and bad manners)

-

___Not sure, no information, I don't know

-

Do they express hostility as a normal feeling during negotiations?

-

___Yes (it is considered normal to express some hostility)

-

___No (it is not acceptable)

-

___Not sure, no information, I don't know

-

Do they express affection during negotiations?

-

___Yes (it is acceptable and normal)

-

___No (it is not common, not customary)

-

___Not sure, no information, I don't know

-

Appendix 4: Formal international negotiation questionnaire

(1) Specifically, think of one concrete formal negotiation in which you participated and which involved people or entities from two countries.

(2) What were the previous issues (interests) leading up to this negotiation? What would have happened to each party if no agreement was reached; what were their alternatives?

(3) How did you and they prepare for this negotiation? What were the prenegotiations? How did they approach you?

(4) How did they decide who was going to negotiate, what would be on the agenda, where the negotiation would take place?

(5) How did the negotiation begin? (Was it a haggling/bargaining process with an excessive opening demand?) Who opened the negotiation? How did each of the parties go about their openings? Were objective criteria sought or established or was it a mere bargaining of positions?

(6) What were the main incidents in the transaction? How did you get the most important points?

(7) How was the closure of the deal? Was it a satisfactory to both parties?

(8) What drew your attention the most in this experience? What did you like most? What did you like least? Do you think people from the other country are similar or dissimilar to you? What are they like?

(9) Do you think this was a typical experience? Have you had experiences with people from the same country or culture that differ much from this one?

(10) What advice would you give someone going to this country to negotiate?

(11) In brief, how do people from this country usually negotiate? What is the difference found in the negotiation you just recounted?

(12) If you had to do this negotiation again, would you change your behavior? What would you do in a different way and why?