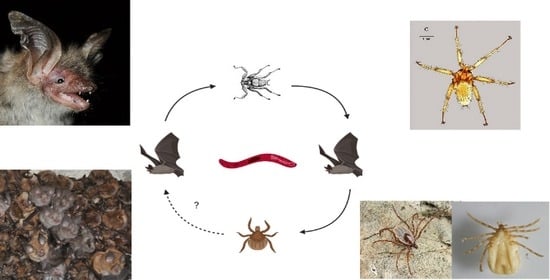

Wide Distribution and Diversity of Malaria-Related Haemosporidian Parasites (Polychromophilus spp.) in Bats and Their Ectoparasites in Eastern Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. World Malaria Report 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 9789241565721. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, K.B.; Campos, P.F.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Kolokotronis, S.O.; Hynes, W.H.; DeSalle, R.; Daszak, P.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Greenwood, A.D. Historical mammal extinction on Christmas Island (Indian Ocean) correlates with introduced infectious disease. PLoS ONE 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Atkinson, C.T.; Thomas, N.J.; Hunter, D.B. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 0813804574. [Google Scholar]

- Dadam, D.; Robinson, R.A.; Clements, A.; Peach, W.J.; Bennett, M.; Rowcliffe, J.M.; Cunningham, A.A. Avian malaria-mediated population decline of a widespread iconic bird species. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 182197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ricklefs, R.E.; Fallon, S.M.; Bermingham, E. Evolutionary relationships, cospeciation, and host switching in avian malaria parasites. Syst. Biol. 2004, 53, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, L.; Robert, V.; Csorba, G.; Hassanin, A.; Randrianarivelojosia, M.; Walston, J.; Nhim, T.; Goodman, S.M.; Ariey, F. Multiple host-switching of Haemosporidia parasites in bats. Malar. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rich, S.M.; Leendertz, F.H.; Xu, G.; LeBreton, M.; Djoko, C.F.; Aminake, M.N.; Takang, E.E.; Diffo, J.L.D.; Pike, B.L.; Rosenthal, B.M. The origin of malignant malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14902–14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutz, H.L.; Patterson, B.D.; Kerbis Peterhans, J.C.; Stanley, W.T.; Webala, P.W.; Gnoske, T.P.; Hackett, S.J.; Stanhope, M.J. Diverse sampling of East African haemosporidians reveals chiropteran origin of malaria parasites in primates and rodents. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 99, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, J.; Pick, C.; Thiede, J.; Kolawole, O.M.; Kingsley, M.T.; Schulze, J.; Cottontail, V.M.; Wellinghausen, N.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Bruchhaus, I. Phylogeny of haemosporidian blood parasites revealed by a multi-gene approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 94, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galen, S.C.; Borner, J.; Martinsen, E.S.; Schaer, J.; Austin, C.C.; West, C.J.; Perkins, S.L. The polyphyly of Plasmodium: Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of the malaria parasites (order Haemosporida) reveal widespread taxonomic conflict. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chellapandi, P.; Prathiviraj, R.; Prisilla, A. Molecular evolution and functional divergence of IspD homologs in malarial parasites. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 65, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R.K.; Eby, P.; Hudson, P.J.; Smith, I.L.; Westcott, D.; Bryden, W.L.; Middleton, D.; Reid, P.A.; McFarlane, R.A.; Martin, G.; et al. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20142124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mühldorfer, K. Bats and Bacterial Pathogens: A Review. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, A.D.; Gama, A.R.; Sodré, M.M.; Savani, E.S.M.M.; Galvão-Dias, M.A.; Jordão, L.R.; Maeda, M.M.; Yai, L.E.O.; Gennari, S.M.; Pena, H.F.J. First isolation and genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii from bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Vet. Parasitol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hornok, S.; Estók, P.; Kováts, D.; Flaisz, B.; Takács, N.; Szoke, K.; Krawczyk, A.; Kontschán, J.; Gyuranecz, M.; Fedák, A.; et al. Screening of bat faeces for arthropod-borne apicomplexan protozoa: Babesia canis and Besnoitia besnoiti-like sequences from Chiroptera. Parasites Vectors 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Molyneux, D.H.; Badfort, J.M. Observations on the Trypanosome of Pipistrellus pipistrellus in Britain, Trypanosoma (Schiszotrypanum) vespertilionis. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. (1920) 1971, 51, 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Garnham, P.C. Types of bat malaria. Riv. Malariol. 1953, 32, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaer, J.; Perkins, S.L.; Decher, J.; Leendertz, F.H.; Fahr, J.; Weber, N.; Matuschewski, K. High diversity of West African bat malaria parasites and a tight link with rodent Plasmodium taxa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witsenburg, F.; Salamin, N.; Christe, P. The evolutionary host switches of Polychromophilus: A multi-gene phylogeny of the bat malaria genus suggests a second invasion of mammals by a haemosporidian parasite. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsenburg, F.; Schneider, F.; Christe, P. Epidemiological traits of the malaria-like parasite Polychromophilus murinus in the Daubenton’s bat Myotis daubentonii. Parasites Vectors 2014, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holz, P.H.; Lumsden, L.F.; Legione, A.R.; Hufschmid, J. Polychromophilus melanipherus and haemoplasma infections not associated with clinical signs in southern bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae bassanii) and eastern bent-winged bats (Miniopterus orianae oceanensis). Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.L.; Schaer, J. A modern menagerie of mammalian malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 32, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megali, A.; Yannic, G.; Christe, P. Disease in the dark: Molecular characterization of Polychromophilus murinus in temperate zone bats revealed a worldwide distribution of this malaria-like disease. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.A.; Molyneaux, D.H.; Stebbings, R.E. Studies on the prevalence of haematozoa of British bats. Mamm. Rev. 1987, 17, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradetti, A.; Verlini, F.; Almieri, C.; Neri, I.; Rostinolla, M. Studi su Polychromophilus melanipherus Dionisi, 1899, e su Polychromophilus murinus Dionisi, 1899. Parassitologia 1961, 3, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Goedbloed, E.; Cremers-Hoyer, L.; Perié, N.M. Blood parasites of bats in the netherlands. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1964, 58, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.A.; Molyneux, D.H. Polychromophilus murinus: A malarial parasite of bats: Life-history and ultrastructural studies. Parasitology 1988, 96, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasindrazana, B.; Goodman, S.M.; Dsouli, N.; Gomard, Y.; Lagadec, E.; Randrianarivelojosia, M.; Dellagi, K.; Tortosa, P. Polychromophilus spp. (Haemosporida) in Malagasy bats: Host specificity and insights on invertebrate vectors. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, C.; Kiefer, A. Bats of Britain and Europe; Bloomsbury Publishing: Lodon, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781472922021. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor, O. An Illustrated Catalogue of the Rotchild Collection of Nycteribiidae in the British Museum; The British Museum: Lodon, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Mihalca, A.D.; Petney, T. Ticks of Europe and North Africa: A Guide to Species Identification; Estrada-Peña, A., Mihalca, A.D., Petney, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-63760-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sándor, A.D.; Corduneanu, A.; Péter, Á.; Mihalca, A.D.; Barti, L.; Csősz, I.; Szőke, K.; Hornok, S. Bats and ticks: Host selection and seasonality of bat-specialist ticks in eastern Europe. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsenburg, F.; Schneider, F.; Christe, P. Signs of a vector’s adaptive choice: On the evasion of infectious hosts and parasite-induced mortality. Oikos 2015, 124, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szentiványi, T.; Markotter, W.; Dietrich, M.; Clément, L.; Ançay, L.; Brun, L.; Genzoni, E.; Kearney, T.; Seamark, E.; Estók, P.; et al. Host conservation through their parasites: Molecular surveillance of vector-borne microorganisms in bats using ectoparasitic bat flies. Parasite 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, A. La malaria di alcune specie di pipistrelli. Atti della Soc. per gli Stud. della Malar. 1899, 1, 133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Garnham, P.C. Polychromophilus species in insectivorous bats. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 67, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, I.; Rosin, G.; Miltgen, F.; Hugot, J.; Leger, N.; Beveridge, I.; Baccam, D. Sur le genre Polycbromophilus-(Haemoproteidae, parasite de Microchiroptères). Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comparée 1980, 55, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikeda, P.; Marinho Torres, J.; Perles, L.; Lourenço, E.C.; Herrera, H.M.; de Oliveira, C.E.; Zacarias Machado, R.; André, M.R. Intra-and Inter-Host Assessment of Bartonella Diversity with Focus on Non-Hematophagous Bats and Associated Ectoparasites from Brazil. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, F.M.; Rais, O.; Humair, P.-F.; Douet, V.; Moret, J.; Gern, L. Identification of host bloodmeal source and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in field-collected Ixodes ricinus ticks in Chaumont (Switzerland). J. Med. Entomol. 2007, 44, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garnham, P.C.C. Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia; Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Sándor, A.D.; Földvári, M.; Krawczyk, A.I.; Sprong, H.; Corduneanu, A.; Barti, L.; Görföl, T.; Estók, P.; Kováts, D.; Szekeres, S.; et al. Eco-epidemiology of Novel Bartonella Genotypes from Parasitic Flies of Insectivorous Bats. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 1076–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sándor, A.D.; Kontschán, J.; Plantard, O.; Péter, Á.; Hornok, S. Illustrated redescription of the male of Ixodes simplex Neumann, 1906. Ticks Tick. Borne. Dis. 2018, 9, 1328–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péter, Á.; Barti, L.; Corduneanu, A.; Hornok, S.; Mihalca, A.D.; Sándor, A.D. First record of Ixodes simplex found on a human host, with a review of cases of human infestation by bat-specialist ticks. Preprint.

- Benda, P.; Ivanova, T.; Horáček, I.; Hanák, V.; Červený, J.; Gaisler, J.; Gueorguieva, A.; Petrov, B.; Vohralík, V. Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of the eastern Mediterranean. Part 3. Review of bat distribution in Bulgaria. Acta Soc. Zool. Bohemicae 2003, 67, 245–357. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A.G. Ecology of insects ectoparasitic on bats. In Ecology of Bats; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1982; pp. 369–401. ISBN 978-94-009-5774-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, C.W.; Dick, S.C. Effects of prior infestation on host choice of bat flies (Diptera: Streblidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2014, 43, 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, C.D.; Krawczyk, A.I.; Sándor, A.D.; Görföl, T.; Földvári, M.; Földvári, G.; Dekeukeleire, D.; Haarsma, A.-J.; Kosoy, M.Y.; Webb, C.T. Host phylogeny, geographic overlap, and roost sharing shape parasite communities in European bats. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Bat Species | Roost Type | Locations | Total | No Positive | Polychromophilus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | (%) | spp. | |||

| Eptesicus serotinus | C | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Miniopterus schreibersii | U | 46 | 46 | 31 (67.4) | Po. melanipherus | |||||||

| Myotis alcathoe | C | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| Myotis blythii | U | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 1 (10.0) | Po. murinus | |||||

| Myotis capaccinii | U | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Myotis daubentonii | U | 1 | 15 | 16 | 9 (56.2) | Po. murinus | ||||||

| Myotis emarginatus | C | 10 | 10 | |||||||||

| Myotis myotis | U | 1 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 6 (75) | Po. murinus | |||||

| Myotis nattereri | C | 12 | 12 | |||||||||

| Nyctalus lasiopterus | C | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Nyctalus noctula | C | 95 | 39 | 134 | ||||||||

| Pipistrellus kuhlii | C | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Pipistrellus nathusii | C | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| Plecotus austriacus | C | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Rhinolophus ferrumequinum | U | 9 | 9 | 1 (11.11) | Po. murinus | |||||||

| Rhinolophus hipposideros | U | 2 | 2 | 1 (50) | Po. murinus | |||||||

| Rhinolophus mehelyi | U | 2 | 2 | 1 (50) | Po. murinus | |||||||

| Vespertilio murinus | C | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| Total | 98 | 115 | 23 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 270 | |||

| Host Species | No Samples (Infested) | I. simplex | I. vespertilionis | Total | Polychromophilus spp. Positive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | N | L | F | N | L | ||||

| Miniopterus schreibersii | 30 (6) | 1 | 48 | 37 | - | - | - | 86 | 16 L, 10 N |

| Myotis daubentonii | 3 (2) | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 L, 1 N |

| Total | 33 (8) | 1 | 48 | 37 | - | 1 | 3 | 90 | 29 (29.2%) |

| Nycteribiidae/Host Species | Bat Fly Sex | Miniopterus schreibersii | Myotis blythii | Myotis capaccinii | Myotis daubentonii | Myotis myotis | No. of Positive Pools (Detected Species) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nycteribia kolenatii | F | 1 | 1 (Po. murinus) | ||||

| M | - | ||||||

| Nycteribia latreillii | F | 2 | - | ||||

| M | 1 | - | |||||

| Nycteribia pedicularia | F | 1 | - | ||||

| M | 2 | - | |||||

| Nycteribia schmidlii | F | 9 | 4 (Po. melanipherus) | ||||

| M | 16 | 3 (Po. melanipherus) | |||||

| Nycteribia vexata | F | - | |||||

| M | 1 | 1 (Po. murinus) | |||||

| Penicillidia conspicua | F | 7 | 4 (Po. melanipherus) | ||||

| M | 4 | 3 (Po. melanipherus) | |||||

| Penicillidia dufourii | F | 1 | 2 | 2 (Po. murinus) | |||

| M | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 (Po. melanipherus), 4 (Po. murinus) | ||

| Total | 39 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sándor, A.D.; Péter, Á.; Corduneanu, A.; Barti, L.; Csősz, I.; Kalmár, Z.; Hornok, S.; Kontschán, J.; Mihalca, A.D. Wide Distribution and Diversity of Malaria-Related Haemosporidian Parasites (Polychromophilus spp.) in Bats and Their Ectoparasites in Eastern Europe. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020230

Sándor AD, Péter Á, Corduneanu A, Barti L, Csősz I, Kalmár Z, Hornok S, Kontschán J, Mihalca AD. Wide Distribution and Diversity of Malaria-Related Haemosporidian Parasites (Polychromophilus spp.) in Bats and Their Ectoparasites in Eastern Europe. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(2):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020230

Chicago/Turabian StyleSándor, Attila D., Áron Péter, Alexandra Corduneanu, Levente Barti, István Csősz, Zsuzsa Kalmár, Sándor Hornok, Jenő Kontschán, and Andrei D. Mihalca. 2021. "Wide Distribution and Diversity of Malaria-Related Haemosporidian Parasites (Polychromophilus spp.) in Bats and Their Ectoparasites in Eastern Europe" Microorganisms 9, no. 2: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020230