Abstract

The monitoring of non-enzymatic post-translational modifications (PTMs) in therapeutic proteins is important to ensure drug safety and efficacy. Together with methionine and asparagine, aspartic acid (Asp) is very sensitive to spontaneous alterations. In particular, Asp residues can undergo isomerization and peptide-bond hydrolysis, especially when embedded in sequence motifs that are prone to succinimide formation or when followed by proline (Pro). As Asp and isoAsp have the same mass, and the Asp-Pro peptide-bond cleavage may lead to an unspecific mass difference of + 18 Da under native conditions or in the case of disulfide-bridged cleavage products, it is challenging to directly detect and characterize such modifications by mass spectrometry (MS). Here we propose a 2D NMR-based approach for the unambiguous identification of isoAsp and the products of Asp-Pro peptide-bond cleavage, namely N-terminal Pro and C-terminal Asp, and demonstrate its applicability to proteins including a therapeutic monoclonal antibody (mAb). To choose the ideal pH conditions under which the NMR signals of isoAsp and C-terminal Asp are distinct from other random coil signals, we determined the pKa values of isoAsp and C-terminal Asp in short peptides. The characteristic 1H-13C chemical shift correlations of isoAsp, N-terminal Pro and C-terminal Asp under standardized conditions were used to identify these PTMs in lysozyme and in the therapeutic mAb rituximab (MabThera) upon prolonged storage under acidic conditions (pH 4–5) and 40 °C. The results show that the application of our 2D NMR-based protocol is straightforward and allows detecting chemical changes of proteins that may be otherwise unnoticed with other analytical methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

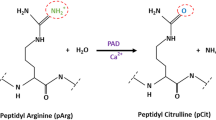

There is a considerable number of modifications that are observed in therapeutic proteins, including tightly controlled enzymatic modifications (e.g., phosphorylation and glycosylation) and spontaneously occurring modifications (e.g., pyroglutamate and succinimide formation, oxidation) (Grassi et al. 2017). Two spontaneous modifications of proteins including therapeutic mAbs are the isomerization of Asp to isoAsp and the non-enzymatic cleavage of the Asp-Xaa peptide bond (Diepold et al. 2012; Harris et al. 2001). Whereas spontaneous cleavage is critically influencing the stability of therapeutic proteins (Vlasak and Ionescu 2011), isomerization of Asp can lead to loss of potency and efficacy (Cacia et al. 1996; Harris et al. 2001; Rehder et al. 2008; Wakankar et al. 2007a; Yan et al. 2016) and even trigger an undesired immunological response (Doyle et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2006). The most sensitive peptide bond prone to spontaneous cleavage was reported to be Asp-Pro (Landon 1977; Piszkiew et al. 1970) with half-lives of months (Li et al. 2009). However, cleavage of other Asp-Xaa bonds was also observed (Vlasak and Ionescu 2011), for example of Asp-Cys (Pane et al. 2016). The cleavage of Asp-Xaa bonds is facilitated, in general, under acidic conditions (Landon 1977; Li et al. 2009; Marcus 1985; Piszkiew et al. 1970; Vlasak and Ionescu 2011). Accordingly, the mechanism of Asp-Xaa peptide-bond cleavage starts with an acid-catalyzed intraresidue nucleophilic attack of the side-chain carboxylate at the backbone carbonyl group, forming a cyclic anhydride intermediate together with the cleavage of the peptide bond, as derived from NMR spectroscopy and isotopic labeling experiments, as well as the analysis of cross-linking products of the reactive anhydride (Joshi et al. 2005; Oliyai and Borchardt 1993; Wang et al. 2019). As a result, the amino acid succeeding Asp is released as new N-terminus, whereas the anhydride intermediate is converted into a C-terminal Asp residue upon water attack at either of the two carbonyl groups. Asp-Xaa peptide-bond cleavage can be also observed as a side reaction of protein splicing, when an Asp is flanking the spliced-out intein (Minteer et al. 2017).

Isomerization of Asp to isoAsp is an important degradation mechanism in proteins and in particular mAbs (Cacia et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2019; Rehder et al. 2008; Wakankar et al. 2007a), which involves succinimide (Snn) formation as an intermediate as proven by 18O labeling (Wang et al. 2007). Unlike the Asp-Xaa cleavage, which requires an intraresidue acid-catalyzed cyclization, the isomerization of Asp to isoAsp involves an interresidue cyclization via the nucleophilic attack by the α-nitrogen of the residue following Asp at the side-chain carboxylate of Asp, resulting in Snn formation upon water elimination (Johnson et al. 1989). Snn is usually stable under mildly acidic conditions (Grassi et al. 2017; Tomizawa et al. 1994), but at neutral to basic pH it is readily hydrolyzed to a mixture of Asp and isoAsp in a ratio of about 1:3 (Geiger and Clarke 1987; Johnson et al. 1989). Although Snn formation is mainly associated with deamidation of Asn residues (Capasso et al. 1995; Geiger and Clarke 1987; Robinson et al. 1970), isomerization of Asp to isoAsp via Snn is important as well. Both Asn deamidation and Asp isomerization occur preferentially at Asx-Gly, Asx-Ser, Asx-Ala and Asx-His (Asx = Asp or Asn) under neutral or mildly acidic conditions (Robinson and Robinson 2001; Yi et al. 2013). However, isomerization at Asp-Asp and Asp-Tyr have been observed in mAbs as well (Kern et al. 2014; Rehder et al. 2008; Yi et al. 2013). Typically, this isomerization is very slow with rates that correspond to half-lives of weeks to years as determined at 37 °C (Li et al. 2009) or few days at 50 °C (Wakankar et al. 2007a, b), both studied under a variety of pH conditions.

Furthermore, the primary structure, local solvent accessibility, and flexibility within a folded protein have a critical influence on deamidation and Asp-isomerization rates (Harris et al. 2001; Wakankar et al. 2007a) and can also influence the ratio of the different products. In unstructured peptides, there is typically an equilibrium between Snn, Asp, and isoAsp (Geiger and Clarke 1987). There is a small number of NMR studies of proteins containing isoAsp of folded, recombinant and mostly 13C/15N labeled proteins, with complete backbone assignments (Chazin et al. 1989; Mallagaray et al. 2019; Revington and Zuiderweg 2004; Rogov et al. 2003; Tugarinov et al. 2002; Wong et al. 2020), whereas not a single NMR study of a folded protein containing Snn is available. However, few examples of protein crystal structures containing Snn can be found in the Protein Data Bank, and the random coil chemical shifts of Snn within peptides have been reported (Grassi et al. 2017). In contrast, the occurrence of isoAsp as a result of isomerization in proteins is probably underestimated as isoAsp is not easily observable by the primary analytical tool used for protein characterization (LC–MS).

Traditionally isoAsp was detected (indirectly) with Edman sequencing, which stops at isoAsp sites (Zhang et al. 2002), but this is not an explicit proof for isoAsp. Another approach involves the enzyme protein-l-isoaspartyl methyltransferase, which specifically methylates isoAsp at its α-carboxyl group leading to a mass difference of 14 Da. However, the methylated isoAsp tends to spontaneously cyclize back to Snn, which in turn is in equilibrium with Asp and isoAsp due to hydrolysis. Furthermore, digestion with Asp-N is used to indirectly localize isoAsp, as Asp-N cleaves N-terminal of Asp but not isoAsp (Zhang et al. 2002).

IsoAsp- and Snn-containing variants of mAbs and their digested peptides could be successfully separated using liquid chromatography like hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) (Cacia et al. 1996; Dick et al. 2009; Eakin et al. 2014), or reversed-phase chromatography (RPC), but for the identification of the signals either synthetic reference peptides are required (Yi et al. 2013) or sophisticated HPLC–MS techniques (Sze et al. 2020) or capillary zone electrophoresis (Bergstrom et al. 2015) have to be applied. In peptides, isoAsp can be distinguished from Asp by ESI-MS2, which shows differences in the intensity ratios of the complementary b and y ions (Lehmann et al. 2000). Also, fragmentation reactions involving electron capture dissociation (ECD) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) are used to distinguish isoAsp from Asp with MS (Cournoyer et al. 2005; DeGraan-Weber et al. 2016; Ni et al. 2010; O'Connor et al. 2006). In any case, a new and orthogonal method to independently detect isoAsp is desireable for cross-validation.

Cleavage of peptide bonds was traditionally detected by SDS-PAGE (Lamed et al. 2001; Lidell and Hansson 2006), and the exact localization of the cleavage was conventionally achieved by Edman sequencing (Lamed et al. 2001; Lidell and Hansson 2006), nowadays by more sophisticated MS techniques (Liu et al. 2008; Osicka et al. 2004). In MS of intact proteins sometimes a mass difference of + 18 Da is observed, which, however, cannot be unambiguously assigned to the cleavage of a peptide bond. Indeed, only under denaturing and reducing conditions the fragments can be separated, and analysis by MS will reveal the cleavage site, which can be further supported by peptide mapping and sequencing by MS2 (Liu et al. 2008). Asp-Pro cleavage has also been reported for mAbs, in particular at Asp270-Pro271 or Asp272-Pro273 in the heavy chain of the Fc part of human immunoglobulin gamma 1 (IgG1) (Davagnino et al. 1995; Rehder et al. 2006; Vlasak and Ionescu 2011) and 2 (IgG2) (Van Buren et al. 2009), respectively.

Nevertheless, quantification of peptide bond cleavage is challenging, especially due to the risk that additional cleavage can occur during the MS measurement (Kim et al. 2013; Maux et al. 2002; Takayama 2016). Therefore complementary methods are of great interest.

Here we report a straightforward NMR approach for the unambiguous detection of both isoAsp formation and backbone cleavage after Asp. With a detailed NMR investigation, we identified characteristic chemical shift correlations to unambiguously detect and potentially quantify these modifications in intact proteins, as illustrated by lysozyme and the biotherapeutic mAb rituximab.

Results

Random coil chemical shifts of C-terminal Asp and N-terminal Pro

To develop an approach for the detection of Asp-Pro cleavage (Fig. 1a), we hypothesized that the new terminal ends, which are formed after peptide bond cleavage, would display characteristic random coil chemical shifts. A complete assignment of a C-terminal Asp (AspC-term) and N-terminal Pro (ProN-term) within small synthetic peptides was obtained under denaturing conditions (7 M urea-d4 in D2O) at the pH values 2.3 and 7.4 (Tables 1 and S1) using 1H-13C HSQC, 1H-1H TOCSY, 1H-13C HMBC, and 1H-13C HMQC-COSY spectra. The two pH conditions were chosen based on previous work on random coil chemical shifts of PTMs, the acidic condition (pH 2.3) for aiding denaturation, the neutral condition (pH 7.4) for fragile moieties. When compared with the random coil chemical shifts of the 20 natural amino acids, we noticed a characteristic cross peak of Cδ–Hδ at 49.3 ppm and ~ 3.4 ppm (Fig. 1b) for the ProN-term, which is separated from other random coil chemical shifts (Fig. 1c). As expected, the random coil chemical shifts of ProN-term did not change much between the two tested pH values (Table 1, Fig. S1). Therefore, also pH values between 2.3 and 7.4 will be suitable for the detection of ProN-term. In the case of AspC-term, the Cβ and Hβ random coil chemical shifts change with pH (Fig. S2), which is mainly due to the ionization state of the side-chain carboxyl group (neutral at pH 2.3 and negatively charged at pH 7.4) and, to a smaller extent, to the ionization state of the C-terminal carboxyl group. Whereas the Cβ–Hβ correlations of AspC-term at pH 2.3 overlap with common random coil chemical shifts (Fig. S2a), the Cβ–Hβ correlations at pH 7.4 are surprisingly distinct from other random coil chemical shifts of Asp within a peptide or protein chain (Fig. S2b). To further study the pH dependence of the chemical shifts, we also measured spectra at different pH values ranging from 1.6 to 9.8 (Fig. 1d, Fig. S3 and Table S2). The data could be fitted using modified Henderson-Hasselbalch equations that account for two titration events resulting in the pKa values of 3.2 and 5.0. Due to the larger chemical shift changes for Hα and Cα around pH 3.2, and for Cβ and Hβ around pH 5.0, the first and second pKa values were assigned to the α- and β-carboxyl group, respectively.

Random coil chemical shift correlations of lysozyme and model peptides for Asp-Pro peptide bond cleavage. a Scheme of the cleavage reaction. b Overlaid 1H-13C HSQC spectra of the three peptides Ac-Gly-Gly-Asp-Pro-Gly-Gly-NH2, H-Pro-Gly-Gly-Gly-NH2 and Ac-Gly-Gly-Gly-Asp-OH recorded under denaturing conditions (7 M urea-d4 + D2O) at pH 7.4. c Comparison of the 1H-13C HSQC spectra of the two reference peptides (H-Pro-Gly-Gly-Gly-NH2, Ac-Gly-Gly-Gly-Asp-OH) with denatured lysozyme (grey) to identify unique random coil chemical shifts suitable for the detection of AspC-term and ProN-term. d Dependence of the chemical shifts of AspC-term on the pH. Data were fitted with a modified Henderson Hasselbalch equation (Eqs. 3 or 4) for extracting two pKa values. The resulting pKa values are given. e 1H-13C HSQC fingerprint spectrum of rituximab (incubated for 138 h at pH 4 and 40 °C) shows specific cross peaks for Cβ-Hβ of C-terminal Asp and Cδ-Hδ of ProN-term (measurement conditions: 7 M urea-d4 in D2O, pH 7.4, 600 MHz, cryo probe, 96 scans, 512 × 256 complex points, 86 h measurement time)

Induction and detection of the cleavage between Asp and Pro at the peptide and protein level

Asp-Pro cleavage was initially studied with the model peptide Ac-Gly-Gly-Asp-Pro-Gly-Gly-NH2 that was incubated for 25 h in D2O at 60 °C and at pH 2.6. A 1H-13C spectrum recorded before and after incubation is shown in Fig. S4. After 25 h approx. 85% of the peptide was already cleaved as judged from the integrals of the cross-peaks.

To induce a detectable amount of Asp-Pro cleavage in a large protein, we chose the therapeutic mAb rituximab, which was incubated in 250 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4) at 40 °C for 138 h. The only Asp-Pro motif in the sequence of rituximab is in the Fc region (Fig. S5). The 1H-13C HSQC spectrum (Fig. 1e) measured under denaturing conditions at pH 7.4 shows characteristic signals of ProN-term as well as AspC-term (Table S6), which unambiguously shows the presence of Asp-Pro cleavage in the treated sample. Investigation with HPLC–MS detected cleavage products confirming the presence of the cleavage between Asp274 and Pro275 as the predominant one (Fig. S6, Table S3).

Also, recombinant Fc/2 protein, which we studied earlier in the context of succinimide formation (Grassi et al. 2017), showed the characteristic signal Cδ-Hδ of ProN-term after treatment at pH 4 (Fig. S7). Since the spectrum of Fc/2 was measured at pH 2.3, we could not detect the characteristic Cβ-Hβ correlations of AspC-term due to signal overlap at this pH value, but the Cα-Hα correlation indicates the presence of AspC-term. The occurrence of backbone cleavage was confirmed by MS (Fig. S7 d, Table S4).

Unique random-coil chemical shifts of isoAsp

In previous work, we observed that the chemical shift correlations of isoAsp at pH 2.3 coincided with typical random coil correlations of the 20 common amino acids (Grassi et al. 2017). Therefore, we decided to change the ionization state of isoAsp aiming to obtain characteristic signals. For this reason, we recorded 1H-13C HSQC spectra of the isoAsp-containing peptide Ac-Gly-Gly-isoAsp-Gly-Gly-NH2 at pH 2.3 as well as pH 7.4 (Fig. 2). As anticipated above, the comparison between the two conditions showed large changes in the chemical shifts of isoAsp (Table 2), hinting that there might be conditions at which the chemical shift correlations are unique. To judge the influence of small pH variations on the chemical shifts and the suitability of certain chemical shift correlations, we measured 1H-13C HSQC spectra at different pH values ranging from 1.27 to 7.6 (Table S5). All chemical shifts of isoAsp changed during the titration. The pH dependence of the chemical shifts (Figs. 2c and S8) was fitted using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (Eq. 3,4) to determine the pKa value of isoAsp (Table 3, Figs. 2c and S8). We determined a value of 3.2. Although we measured the pKa in D2O with direct reading of the H2O-calibrated pH-meter (pKaH*), it was noticed previously that pKaH* measurements in D2O are just about 0.06 pH units higher than pKa values measured in H2O (pKaH), at least under acidic conditions (Bundi and Wüthrich 1979). In a more recent study deviations of < 0.2 pH units were observed between pKaH* and pKaH for carboxyl groups in short peptides (Krezel and Bal 2004).

Overlay of the reference peptides containing Asp and isoAsp in protonated and deprotonated form. a Overlay of 1H-13C HSQC spectra of the peptide Ac-Gly-Gly-isoAsp-Gly-Gly-NH2 at the two pH values 2.3 (blue) and 7.4 (red). Furthermore Snn can be detected due to the equilibrium between isoAsp and Snn. # impurity of cyclo(Gly-Asp) diketopiperazine peptide, whose signals are pH independent. b Overlay of 1H-13C HSQC spectra of the peptide Ac-Gly-Gly-Asp-Pro-Gly-Gly-NH2 at the two pH values 2.3 (blue) and 7.4 (red). As Asp has typically a pKa value of approx. 3.9 (Platzer et al. 2014), the random coil chemical shifts of protonated and deprotonated Asp change significantly. c Dependence of the chemical shifts of isoAsp on the pH. Data were fitted with a modified Henderson Hasselbalch equation (Eqs. 3 or 4) for extracting the pKa value. The resulting pKa values are given

The titration data revealed that neutral pH seems to be ideally suitable to unambiguously detect Cβ-Hβ correlations of isoAsp, because the chemical shifts do not depend on small pH changes and the signals do not overlap with the random coil chemical shifts of natural amino acids.

The characteristic signals of isoAsp could be detected in a 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of denatured lysozyme that was incubated at pH 4 for 138 h (Fig. 3a). These signals were absent in the spectrum of untreated lysozyme (Fig. 3b). This example illustrates that a 1H-13C HSQC fingerprint spectrum can identify (unambiguously) isoAsp in denatured proteins.

Detection of isoAsp in incubated lysozyme showing the unique Cβ-Hβ chemical shift correlations of isoAsp in a 1H-13C HSQC spectrum at pH 7.4 under denaturing conditions. a The 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of lysozyme (concentration: 36 mg/mL) incubated for 10 days at pH 4 and 40 °C recorded with 120 scans (3 days measurement time) and 512 × 512 complex points. The isoAsp Cβ–Hβ correlations are well isolated and suited for detection and quantification. As a negative control, panel b shows a 1H 13C HSQC spectrum of non-treated lysozyme (concentration: 36 mg/mL, 120 scans, 512 × 512 complex points, 3 days measurement time)

Discussion

Our long-term goal is to use a 1H-13C HSQC spectrum of a biotherapeutic protein to identify and quantify spontaneous or enzymatic modifications with a single experiment using characteristic chemical shifts correlations measured under denaturing conditions. Such an initial screening of prospective biotherapeutics treated under induced degradation conditions will be enormously valuable to identify any potential modification that can occur during processing, formulation, and storage. This is valuable information, because many analytical techniques, especially MS, typically require that the modifications to be monitored are known beforehand. In contrast, NMR spectroscopy can also identify less-established (Schweida et al. 2019) or completely unknown modifications.

The NMR assignments presented here for C-terminal Asp, N-terminal Pro, and internal isoAsp residues under denaturing conditions at pH 2.3 and 7.4 are suited to detect the cleavage of Asp-Xaa peptide bonds in denatured proteins (excepted proteins with Xaa and Asp as amino- and carboxyl termini, respectively), and to identify isoAsp resulting from either Asn deamidation or Asp isomerization. For C-terminal Asp, the key correlations of Cβ-Hβ are unique at pH 7.4 and in this case do not overlap with the random coil chemical shifts of the 20 natural amino acids. Therefore, the Cβ-Hβ at pH 7.4 is well suited to unambiguously identify and quantify peptide bond cleavage between Asp and any following amino acid (Asp-Xaa). An Asp-Pro cleavage can be further identified by a unique 1H-13C correlation of Cδ-Hδ of the ProN-term, which is not influenced by the pH. For isoAsp, the Cβ-Hβ random coil chemical shift correlations are well-separated from those of Asp at pH 7.4, and they can be used to identify and potentially quantify isoAsp in intact proteins under denaturing conditions.

The pKa values of isoAsp and AspC-term, which we determined for choosing appropriate pH conditions, will be also valuable for other analytical techniques like capillary electrophoresis, for a better understanding of the role of electrostatic effects in enzyme mechanisms, molecular modeling, and more advanced theoretical approaches. The pKa value of the isoAsp side chain was determined to be 3.2 (Table 3, Figs. 2c, S8), which is 0.7 pH units lower than the pKa value reported for an Asp side chain (approx. 3.9) (Platzer et al. 2014). The two pKa values of AspC-term (Table 3) were 3.4 for the backbone carboxyl group and 5.0 for the side chain. Interestingly, the acidity of the α-carboxyl group is the same for internal isoAsp and C-terminal Asp, whereas the acidity of the β-carboxyl group is significantly lower in a C-terminal Asp than in an internal Asp residue (5.0 versus approx. 3.9). This is in agreement with an earlier report, where a pKa value of 4.5 was measured for the side chain of an internal Asp flanked by two Glu residues in an intrinsically disordered protein, which was explained with the presence of other negatively charged groups in the proximity (Neira et al. 2016).

Conclusion

We demonstrate here the application of 2D NMR spectroscopy to unambiguously identify protein degradation products derived from Asp-Xaa peptide-bond cleavage, Asp isomerization, or Asn deamidation in any protein that can be denatured. There is no limit concerning the protein size as long as the denatured protein remains in solution, and the straightforward approach can be applied to any modern NMR instrument with medium to high field and two or more channels. Considering the importance of ensuring the safety and efficacy of therapeutic proteins, unambiguous identification of all potentially occurring modifications is crucial. Although not suitable for high-throughput routine applications, our NMR approach is ideal for cross-validation purposes, in combination with MS-based characterization of biotherapeutics.

Experimental section

Chemicals for peptide synthesis

Chemical reagents and solvents for the peptide synthesis were of peptide-synthesis grade; solvents for HPLC were of HPLC grade. Fmoc-protected amino acids, Rink-amide MBHA resin (100–200 mesh, loading 0.57 mmol/g), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), piperidine, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), dichloromethane (DCM), diethyl ether, and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from Iris Biotech (Germany). H-Asp(OtBu)-2-chlorotrityl resin (loading 0.60 mmol/g) was purchased from Merck Schuchardt OHG (Germany). Thioanisole (TIA), acetic anhydride, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, triisopropylsilane (TIS), 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT), and acetonitrile (ACN) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Germany). 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) were purchased from Biosolve (The Netherlands).

Solid-phase peptide synthesis

Peptides (Table S1) were synthesized by Fmoc-chemistry using solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) on an automatic peptide synthesizer (Syro I, Biotage). The resin-bound peptides were cleaved and deprotected with TFA containing 10% scavenger mixture H2O/TIA/EDT/TIS (1:3:3:3) at room temperature for 1.5 h. The peptides were then precipitated from cold diethyl ether, recovered by centrifugation at 4 °C, washed three times with cold ether, dried under nitrogen, dissolved in 0.1% aqueous TFA, and lyophilized.

Peptide characterization

Analytical RP‐HPLC was performed using a Thermo Scientific™ Dionex™ UltiMate™ 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germering, Germany) and a Syncronis C‐18 column (100 Å, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The UV detection was set at 220 nm. The elution system was (A) 0.06% (v/v) TFA in water, and (B) 0.05% (v/v) TFA in ACN. The peptides were dissolved in ACN/H2O (10:90, v/v) containing 0.1% TFA. Analytical chromatograms were obtained with the following gradient: 1% B for 8 min, then to 50% B in 35 min. Mass spectra were recorded on an Autoflex Speed MALDI‐TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) by using α‐cyano‐4‐hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix.

Sample treatment and preparation

Rituximab and reference peptides

For rituximab, the buffer of 2 mL formulation solution of Mabthera (Mabthera, Roche; exp. year: 2013, 2 mL, 10 mg/mL) was exchanged to 0.25 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4) with Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (Cutoff: 30 kDa, Merck) and the sample was incubated for 138 h at 40 °C. Afterward, the buffer was changed to ddH2O overnight with a Spectra/Por dialysis membrane and lyophilized. For NMR measurements the sample was dissolved in 500 μL of a 7 M urea-d4 (98 atom%D, ARMAR Chemicals) solution in D2O (100 at.% D, ARMAR Chemicals) resulting in a concentration of 30 to 40 mg/mL mAb. Urea solutions were freshly prepared to minimize the formation of isocyanic acid which leads to carbamylation of lysine residues. For reducing the disulfide bonds, approx. 1–1.6 mg of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the sample corresponding approximately to 11 mmol L−1 followed by incubation at 60 °C for 15 min. The pH was adjusted to 2.3 or 7.4 by adding DCl or NaOD (ARMAR Chemicals), respectively.

1 to 2 mg of each reference peptide (Table 2) was dissolved at the same conditions as full-length rituximab but without TCEP treatment. Afterward, the pH was adjusted to 2.3 or 7.4 by adding DCl or NaOD (ARMAR Chemicals), respectively.

Lysozyme

To induce the formation of isoAsp, 75 mg lysozyme powder from chicken egg white (L4919, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 50 mL 0.5 M ammonium acetate (pH adjusted to 4) and incubated for 10 days at 40 °C. Afterward, the buffer was changed to ddH2O via dialysis with a Spectra/Por dialysis membrane (cutoff 3.5 kDa) and lyophilized. For one NMR sample an amount of 18 mg of treated or non-treated lysozyme was dissolved in 500 μl 7 M urea-d4 (98 atom%D, ARMAR Chemicals) solution in D2O (100 atom%D, ARMAR Chemicals). For reducing disulfide bonds, 1–1.6 mg TCEP was added and the sample was incubated at 60 °C for 15 min. The pH was adjusted to 2.3 (DCl, ARMAR Chemicals) or 7.4 (NaOD, ARMAR Chemicals), respectively.

Mass spectrometry

The lysozyme and recombinant Fc/2 samples were diluted in 0.10% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (FA) to a final concentration of 0.50 mg.mL−1. Intramolecular disulfide bonds were reduced with 5 mmol L−1 tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) at 60 °C for 30 min. Five microliters of sample were injected in in-line split-loop mode on the HPLC system described earlier (Grassi et al. 2017), using a Waters XBridge Protein BEH C4 column (150 × 2.1 mm i.d., 3.5 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size) operated at a column temperature of 60 °C. Mobile phase A was H2O + 0.10% FA, mobile phase B was composed of acetonitrile (ACN) + 0.10% FA, the applied flow rate was 200 μL min−1. The separation was performed with an initial equilibration at 5.0% B for 5 min, followed by a linear gradient of 5.0−50.0% B in 20 min, column regeneration at 99.99% B for 10 min, and re-equilibration at 5.0% B for 15 min. Mass spectrometry was conducted on a Thermo Scientific™ Q Exactive™ Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer equipped with an Ion Max™ source with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) probe. The instrument settings were as follows: source heater temperature of 200 °C, spray voltage of 3.5 kV, sheath gas flow of 20 arbitrary units, auxiliary gas flow of 5 arbitrary units, capillary temperature of 250 °C, S-lens RF level of 70.0, in-source CID of 20.0 eV, AGC target of 1e6 and maximum injection time of 200 ms. The measurements were carried out in full scan mode with a range of m/z 500–2500 at a resolution setting of 140,000 at m/z 200.

Rituximab drug product sample was diluted to a concentration of 5.0 mg mL−1 in 175 mmol L−1 ammonium acetate. Subsequently, disulfides were reduced in 4 mol L−1 GdnHCl with 5 mmol L−1 TCEP for 15 min at 60 °C. Rituximab was analyzed employing the same HPLC–MS set up with the same mobile phases but different settings: The column used for separation was a Thermo Scientific™ MAbPac™ RP column (150 × 2.1 mm i.d., 4.0 μm particle size,∼1500 Å pore size) operated at 70 °C and a flow rate of 200 μL min−1. The gradient applied was the following: 10.0% B for 2 min, 20.0 − 35.0% B in 10.5 min, 80% B for 2.5 min, and 10.0% B for 10 min. The instrument settings of the mass spectrometer were as follows: spray voltage of 3.5 kV, sheath gas flow of 15 arbitrary units, auxiliary gas flow of 5 arbitrary units, in-source CID of 40.0 eV, capillary temperature of 300 °C, S-lens RF level of 80.0, AGC target of 1e6, and maximum injection time of 200 ms. The measurements were carried out in full scan mode with a range of m/z 1000−4000 at a resolution setting of 140,000 at m/z 200. For deconvolution of raw mass spectra into zero charge-state spectra the Xtract algorithm integrated into the Thermo Scientific™ BioPharma Finder™ software version 4.0 was used.

NMR spectroscopy

Spectra were recorded on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer equipped with a 1H/13C/15N/31P quadruple-resonance room temperature probe at 298 K, except incubated rituximab that was measured on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer equipped with a cryogenetic 1H/13C/15N/31P quadruple-resonance probe (QCI). For all the NMR measurements, standard 5 mm NMR tubes (ARMAR, Type 5TA) were used with a sample volume of 500 μL. The HSQC fingerprint spectra of the reference peptides were assigned using the following 2D experiments: 1H-13C HSQC, 1H-13C HMBC (hmbcgpndqf), 1H-1H TOCSY, 1H-1H COSY (cosygpppqf), 1H-13C HMQC-COSY, 1H-1H ROESY, 1H-15N HSQC, and 1H-13C HCO (Grassi et al. 2017). For measuring and processing the Data, Topspin 3.5/3.6.1 (Bruker) was used. Sparky 3.114 (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco, USA) was used for analyzing the NMR data.

For referencing, 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) (ARMAR Chemicals) was added to the samples after measuring the initial spectra. A 1D 1H experiment was performed for referencing the proton chemical shift. The carbon and nitrogen dimensions were referenced according to the IUPAC-IUB recommended chemical shifts referencing ratios of 0.251449530 (13C) and 0.101329118 (15N) (Markley et al. 1998). Chemical shift assignments of all peptides were deposited in the BioMagResBank (Ulrich et al. 2008) under accession numbers 50598, 50599, 50600 and 50601.

pKa determination of isoAsp and AspC-term

For the determination of the pKa values of isoAsp and AspC-term, 2 mg of the peptides Ac-Gly-Gly-isoAsp-Gly-Gly-NH2 or Ac-Gly-Gly-Gly-Asp-OH were dissolved in 500 µl D2O. For referencing, 5 µl (100 mM) DSS solution was added. The pH was stepwise adjusted with 0.1 to 1 M NaOD or 0.1 to 1 M DCl (Tables S2, S5). The pH values were measured at room temperature (approx. 25 °C) and the pH meter (EL20 pH-meter, Mettler Toledo) with the pH electrode (MiniTrode, Hamilton) was calibrated using fresh standards at pH 4.00 and 7.00 (AVS TITRINORM, VWR Chemicals). For all of the pH steps, 1H 1D and 1H-13C spectra were measured. The chemical shifts of isoAsp and AspC-term plotted as a function of pH were fitted using the modified Henderson-Hasselbalch equations (Eqs. 1, 2, 3, and 4) (Farrell et al. 2010; Silverstein 2012) yielding the pKa values. For the Cα of isoAsp (Eqs. 3,4), δobs is the pH-dependent chemical shift, and δmin and δmax correspond to the chemical shifts of the fully protonated and fully deprotonated form, respectively. As AspC-term (Eqs. 1,2) has two ionizable groups, the equation considers two pKa values (pKa1 and pKa2). For the Cα of AspC-term, δobs is the pH-dependent chemical shift, and δmin0 and δmax2 correspond to the chemical shift of the fully protonated (C-terminal and side chain carboxylic group) and fully deprotonated form (C-terminal and side chain carboxylic group), respectively. δmax1 and δmin1 are the chemical shifts of the fully protonated side chain and fully deprotonated C-terminal carboxylic group, respectively. The pKa values were calculated using the software ORIGIN Pro 2019 (OriginLab Corporation) using the following functions:

References

Bergstrom T, Fredriksson SA, Nilsson C, Astot C (2015) Deamidation in ricin studied by capillary zone electrophoresis- and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B 974:109–117

Bundi A, Wüthrich K (1979) 1H-NMR parameters of the common amino-acid residues measured in Aaqueous-solutions of the linear tetrapeptides H-Gly-Gly-X-L-Ala-OH. Biopolymers 18:285–297

Cacia J, Keck R, Presta LG, Frenz J (1996) Isomerization of an aspartic acid residue in the complementarity-determining regions of a recombinant antibody to human IgE: identification and effect on binding affinity. Biochemistry 35:1897–1903

Capasso S, Kirby AJ, Salvadori S, Sica F, Zagari A (1995) Kinetics and mechanism of the reversible isomerization of aspartic-acid residues in tetrapeptides. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2:2437–2442

Chazin WJ, Kordel J, Thulin E, Hofmann T, Drakenberg T, Forsen S (1989) Identification of an isoaspartyl linkage formed upon deamidation of bovine calbindin-D9k and structural characterization by 2D 1H-NMR. Biochemistry 28:8646–8653

Cournoyer JJ, Pittman JL, Ivleva VB, Fallows E, Waskell L, Costello CE, O’Connor PB (2005) Deamidation: differentiation of aspartyl from isoaspartyl products in peptides by electron capture dissociation. Protein Sci 14:452–463

Davagnino J, Wong C, Shelton L, Mankarious S (1995) Acid-hydrolysis of monoclonal-antibodies. J Immunol Methods 185:177–180

DeGraan-Weber N, Zhang J, Reilly JP (2016) Distinguishing aspartic and isoaspartic acids in peptides by several mass spectrometric fragmentation methods. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 27:2041–2053

Dick LW, Qiu DF, Cheng KC (2009) Identification and measurement of isoaspartic acid formation in the complementarity determining region of a fully human monoclonal antibody. J Chromatogr B 877:3841–3849

Diepold K, Bomans K, Wiedmann M, Zimmermann B, Petzold A, Schlothauer T, Mueller R, Moritz B, Stracke JO, Molhoj M, Reusch D, Bulau P (2012) Simultaneous assessment of Asp isomerization and Asn deamidation in recombinant antibodies by LC-MS following incubation at elevated temperatures. PLoS ONE 7:e30295

Doyle HA, Zhou J, Wolff MJ, Harvey BP, Roman RM, Gee RJ, Koski RA, Mamula MJ (2006) Isoaspartyl post-translational modification triggers anti-tumor T and B lymphocyte immunity. J Biol Chem 281:32676–32683

Eakin CM, Miller A, Kerr J, Kung J, Wallace A (2014) Assessing analytical methods in monoclonal antibodies to monitor isoAsp formation. Front Pharmacol 5:87

Farrell D, Miranda ES, Webb H, Georgi N, Crowley PB, McIntosh LP, Nielsen JE (2010) Titration_DB: storage and analysis of NMR-monitored protein pH titration curves. Proteins 78:843–857

Geiger T, Clarke S (1987) Deamidation, isomerization, and racemization at asparaginyl and aspartyl residues in peptides-succinimide-linked reactions that contribute to protein-degradation. J Biol Chem 262:785–794

Grassi L, Regl C, Wildner S, Gadermaier G, Huber CG, Cabrele C, Schubert M (2017) Complete NMR assignment of succinimide and its detection and quantification in peptides and intact proteins. Anal Chem 89:11962–11970

Harris RJ, Kabakoff B, Macchi FD, Shen FJ, Kwong M, Andya JD, Shire SJ, Bjork N, Totpal K, Chen AB (2001) Identification of multiple sources of charge heterogeneity in a recombinant antibody. J Chromatogr B 752:233–245

Johnson BA, Shirokawa JM, Hancock WS, Spellman MW, Basa LJ, Aswad DW (1989) Formation of isoaspartate at 2 distinct sites during invitro aging of human growth-hormone. J Biol Chem 264:14262–14271

Joshi AB, Sawai M, Kearney WR, Kirsch LE (2005) Studies on the mechanism of aspartic acid cleavage and glutamine deamidation in the acidic degradation of glucagon. J Pharm Sci 94:1912–1927

Kern W, Mende R, Denefeld B, Sackewitz M, Chelius D (2014) Ion-pair reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography method for the quantification of isoaspartic acid in a monoclonal antibody. J Chromatogr B 955:26–33

Kim JS, Monroe ME, Camp DG, Smith RD, Qian WJ (2013) In-source fragmentation and the sources of partially tryptic peptides in shotgun proteomics. J Proteome Res 12:910–916

Krezel A, Bal W (2004) A formula for correlating pK(a) values determined in D2O and H2O. J Inorg Biochem 98:161–166

Lamed R, Kenig R, Morag E, Yaron S, Shoham Y, Bayer EA (2001) Nonproteolytic cleavage of aspartyl proline bonds in the cellulosomal scaffoldin subunit from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 90:67–73

Landon M (1977) Cleavage at aspartyl-prolyl bonds. Methods Enzymol 47:145–149

Lehmann WD, Schlosser A, Erben G, Pipkorn R, Bossemeyer D, Kinzel V (2000) Analysis of isoaspartate in peptides by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Protein Sci 9:2260–2268

Li N, Fort F, Kessler K, Wang W (2009) Factors affecting cleavage at aspartic residues in model decapeptides. J Pharm Biomed Anal 50:73–78

Lidell ME, Hansson GC (2006) Cleavage in the GDPH sequence of the C-terminal cysteine-rich part of the human MUC5AC mucin. Biochem J 399:121–129

Liu HC, Gaza-Bulseco G, Lundell E (2008) Assessment of antibody fragmentation by reversed-phase liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B 876:13–23

Lu XJ, Nobrega RP, Lynaugh H, Jain T, Barlow K, Boland T, Sivasubramanian A, Vasquez M, Xu YD (2019) Deamidation and isomerization liability analysis of 131 clinical-stage antibodies. mAbs 11:45–57

Mallagaray A, Creutznacher R, Dulfer J, Mayer PHO, Grimm LL, Orduna JM, Trabjerg E, Stehle T, Rand KD, Blaum BS, Uetrecht C, Peters T (2019) A post-translational modification of human Norovirus capsid protein attenuates glycan binding. Nat Commun 10:1320

Marcus F (1985) Preferential cleavage at aspartyl-prolyl peptide-bonds in dilute acid. Int J Pept Prot Res 25:542–546

Markley JL, Bax A, Arata Y, Hilbers CW, Kaptein R, Sykes BD, Wright PE, Wüthrich K (1998) Recommendations for the presentation of NMR structures of proteins and nucleic acids-IUPAC-IUBMB-IUPAB Inter-Union Task Group on the standardization of data bases of protein and nucleic acid structures determined by NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR 12:1–23

Maux D, Enjalbal C, Martinez J, Aubagnac JL (2002) New example of proline-induced fragmentation in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of peptides. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 16:1470–1475

Minteer CJ, Siegart NM, Colelli KM, Liu X, Linhardt RJ, Wang C, Gomez AV, Reitter JN, Mills KV (2017) Intein-promoted cyclization of aspartic acid flanking the intein leads to atypical N-terminal cleavage. Biochemistry 56:1042–1050

Neira JL, Rizzuti B, Iovanna JL (2016) Determinants of the pK(a) values of ionizable residues in an intrinsically disordered protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 598:18–27

Ni WQ, Dai SJ, Karger BL, Zhou ZHS (2010) Analysis of isoaspartic acid by selective proteolysis with Asp-N and electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 82:7485–7491

O’Connor PB, Cournoyer JJ, Pitteri SJ, Chrisman PA, McLuckey SA (2006) Differentiation of aspartic and isoaspartic acids using electron transfer dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 17:15–19

Oliyai C, Borchardt RT (1993) Chemical pathways of peptide degradation. 4. Pathways, kinetics, and mechanism of degradation of an aspartyl residue in a model hexapeptide. Pharm Res 10:95–102

Osicka R, Prochazkova K, Sulc M, Linhartova I, Havlicek V, Sebo P (2004) A novel “clip-and-link” activity of repeat in toxin (RTX) proteins from gram-negative pathogens: covalent protein cross-linking by an Asp-Lys isopeptide bond upon calcium-dependent processing at an Asp-Pro bond. J Biol Chem 279:24944–24956

Pane K, Durante L, Pizzo E, Varcamonti M, Zanfardino A, Sgambati V, Di Maro A, Carpentieri A, Izzo V, Di Donato A, Cafaro V, Notomista E (2016) Rational design of a carrier protein for the production of recombinant toxic peptides in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 11:e0146552

Piszkiew D, Landon M, Smith EL (1970) Anomalous cleavage of aspartyl-proline peptide bonds during amino acid sequence determinations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 40:1173–1178

Platzer G, Okon M, McIntosh LP (2014) pH-dependent random coil H-1, C-13, and N-15 chemical shifts of the ionizable amino acids: a guide for protein pK (a) measurements. J Biomol NMR 60:109–129

Rehder DS, Chelius D, McAuley A, Dillon TM, Xiao G, Crouse-Zeineddini J, Vardanyan L, Perico N, Mukku V, Brems DN, Matsumura M, Bondarenko PV (2008) Isomerization of a single aspartyl residue of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor immunoglobulin gamma 2 antibody highlights the role avidity plays in antibody activity. Biochemistry 47:2518–2530

Rehder DS, Dillon TM, Pipes GD, Bondarenko PV (2006) Reversed-phase liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of reduced monoclonal antibodies in pharmaceutics. J Chromatogr A 1102:164–175

Revington M, Zuiderweg ERP (2004) TROSY-driven NMR backbone assignments of the 381-residue nucleotide-binding domain of the Thermus Thermophilus DnaK molecular chaperone. J Biomol NMR 30:113–114

Robinson AB, Mckerrow JH, Cary P (1970) Controlled deamidation of peptides and proteins: an experimental hazard and a possible biological timer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 66:753–757

Robinson NE, Robinson AB (2001) Prediction of protein deamidation rates from primary and three-dimensional structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:4367–4372

Rogov VV, Lucke C, Muresanu L, Wienk H, Kleinhaus I, Werner K, Lohr F, Pristovsek P, Ruterjans H (2003) Solution structure and stability of the full-length excisionase from bacteriophage HK022. Eur J Biochem 270:4846–4858

Schweida D, Barraud P, Regl C, Loughlin FE, Huber CG, Cabrele C, Schubert M (2019) The NMR signature of gluconoylation: a frequent N-terminal modification of isotope-labeled proteins. J Biomol NMR 73:71–79

Silverstein TP (2012) Fitting imidazole H-1 NMR titration data to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. J Chem Educ 89:1474–1475

Sze SK, JebaMercy G, Ngan SC (2020) Profiling the “deamidome” of complex biosamples using mixed-mode chromatography-coupled tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2020.1005.1005

Takayama M (2016) MALDI in-source decay of protein: the mechanism of c-Ion formation. Mass Spectrom (Tokyo) 5:A0044

Tomizawa H, Yamada H, Ueda T, Imoto T (1994) Isolation and characterization of 101-succinimide lysozyme that possesses the cyclic imide at Asp101-Gly102. Biochemistry 33:8770–8774

Tugarinov V, Muhandiram R, Ayed A, Kay LE (2002) Four-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of a 723-residue protein: chemical shift assignments and secondary structure of malate synthase G. J Am Chem Soc 124:10025–10035

Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, Harano Y, Ioannidis YE, Lin J, Livny M, Mading S, Maziuk D, Miller Z, Nakatani E, Schulte CF, Tolmie DE, Wenger RK, Yao HY, Markley JL (2008) BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D402–D408

Van Buren N, Rehder D, Gadgil H, Matsumura M, Jacob J (2009) Elucidation of two major aggregation pathways in an IgG2 antibody. J Pharm Sci 98:3013–3030

Vlasak J, Ionescu R (2011) Fragmentation of monoclonal antibodies. mAbs 3:253–263

Wakankar AA, Borchardt RT, Eigenbrot C, Shia S, Wang YJ, Shire SJ, Liu JL (2007a) Aspartate isomerization in the complementarity-determining regions of two closely related monoclonal antibodies. Biochemistry 46:1534–1544

Wakankar AA, Liu J, Vandervelde D, Wang YJ, Shire SJ, Borchardt RT (2007b) The effect of cosolutes on the isomerization of aspartic acid residues and conformational stability in a monoclonal antibody. J Pharm Sci 96:1708–1718

Wang W, Singh S, Zeng DL, King K, Nema S (2007) Antibody structure, instability, and formulation. J Pharm Sci 96:1–26

Wang Z, Friedrich MG, Truscott RJW, Schey KL (2019) Cleavage C-terminal to Asp leads to covalent crosslinking of long-lived human proteins. Biochem Biophys Acta 1867:831–839

Wong LE, Kim TH, Muhandiram DR, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE (2020) NMR experiments for studies of dilute and condensed protein phases: application to the phase-separating protein CAPRIN1. J Am Chem Soc 142:2471–2489

Yan YT, Wei H, Fu Y, Jusuf S, Zeng M, Ludwig R, Krystek SR, Chen GD, Tao L, Dast TK (2016) Isomerization and oxidation in the complementarity-determining regions of a monoclonal antibody: a study of the modification-structure-function correlations by hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 88:2041–2050

Yang ML, Doyle HA, Gee RJ, Lowenson JD, Clarke S, Lawson BR, Aswad DW, Mamula MJ (2006) Intracellular protein modification associated with altered T cell functions in autoimmunity. J Immunol 177:4541–4549

Yi L, Beckley N, Gikanga B, Zhang J, Wang YJ, Chih HW, Sharma VK (2013) Isomerization of AspAsp motif in model peptides and a monoclonal antibody fab fragment. J Pharm Sci 102:947–959

Zhang W, Czupryn MJ, Boyle PT, Amari J (2002) Characterization of asparagine deamidation and aspartate isomerization in recombinant human interleukin-11. Pharm Res 19:1223–1231

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Novartis for kindly providing expired samples of reference medicines (rituximab, Mabthera, Roche), Dr. Urs Lohrig from Novartis, Dr. Kai Scheffler, Dr. Kyle D'Silva, Dr. Anthony Squibb, and Dr. Frank Steiner from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Dr. Lawrence McIntosh (University of British Columbia) for comments on the manuscript as well as scientific discussions. The Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy Platform at the ETH Zürich, Dr. Alvar Gossert, and Dr. Simon Rüdisser (both ETH Zürich) for access to a 600 MHz Bruker with cryogenic probe and technical support. The work was supported by the Austrian Federal Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs, The National Foundation of Research, Technology, and Development, and a Start-up Grant of the State of Salzburg.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS, CC, and AH designed the experiments. VS synthesized and characterized the reference peptides. AH and MS performed the NMR experiments and assigned the NMR resonances. CR performed and interpreted the mass spectrometry experiments. CH supervised the mass spectrometry analysis. MS, CC, AH, and VS wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The salary of Arthur Hinterholzer was fully funded and Christian G. Hubers salary is partly funded by the Christian Doppler Laboratory for Biosimilar Characterization, which is partly supported by Novartis and Thermo Fisher Scientific. The authors declare no other competing financial interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hinterholzer, A., Stanojlovic, V., Regl, C. et al. Detecting aspartate isomerization and backbone cleavage after aspartate in intact proteins by NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR 75, 71–82 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10858-020-00356-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10858-020-00356-4