Abstract

We exploit local and temporal variation in the availability of public childcare for children under the age of three that induces exogenous variation in childcare attendance. We find a weak, positive average treatment effect (ATE) on maternal labor supply. The estimation of the average treatment effect is interesting – however, possibly masking important effect heterogeneity. Examining selection behavior and estimating marginal treatment effects along the distribution of observables and unobservables that drive individual treatment decisions reveal transmission channels and uncover substantial heterogeneity in marginal returns from public childcare reforms. By estimating marginal returns, we detect reverse selection on gains at the intensive margin, whereas a substantial share (40 percent) of mothers with median desire to public childcare react with increased probability to work full time. Thus, if the supply of public childcare is expanded from a modest to a more generous level of coverage, those with average resistance towards early public childcare do gain. At the extensive margin, positive selection on gains is found; however, only a small fraction of mothers with the lowest distaste for early public childcare shift from non-employment to part-time jobs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The provision of high-quality public childcare is seen as a central instrument to equalize children’s initial conditions for life and to complement the acquisition of human capital (see Cornelissen et al. 2018; Felfe and Lalive 2018). The German government formulates the promotion of childcare for children under the age of three as an equalizer from a second perspective (German Federal Parliament 2008)—one that involves mothers who wish to combine motherhood and work—a combination which is challenging due to restrictions in the supply of public childcare. In the underlying standard microeconomic model, a policy reform that increases the supply of childcare and that holds fees constant is expected to increase the labor market supply of mothers. This policy reform may also shorten the time being out of the labor force so that depreciation of human capital is reduced during time-out and re-entry wages are higher. Increased hourly wages can enable the achievement of a given monthly income with less working hours, so there could also be a negative relationship between childcare and labor supply at the intensive margin of employment (see Carta and Rizzica 2018).

While eligibility to childcare slots in the United States and Canada is often targeted at some explicitly defined groups of particular need (Blau 2000; Cascio 2009; Fitzpatrick 2010, 2012; Kline and Walters 2016), public childcare is very often of universal shape in Europe. Two strands of identification strategies appear to be dominant when quasi-experimental data is available (see Table 1):Footnote 1 The first strategy examines the effect of differences in spatial childcare coverage at the level of municipalities on individual labor supply by estimating an intend-to-treat (ITT) effect. The second strategy applies regression discontinuity designs (RDD) using age-related cut-off rules to capture eligibility to a public childcare slot and exploits the fact that the eligibility depends on the month of birth.Footnote 2

First, the overview on European studies underline that estimates are hard to compare because the institutional setting varies much by countries (e.g., the age group of children under focus, the initial level of childcare supply, general female employment, economic conditions, and the system of other instruments of family policy differ). Second, the effects on maternal employment are smallFootnote 3 and only Goux and Mourin (2010) and Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) provide information regarding actual childcare utilization that enables the identification of an ATE, not solely an ITT. The lack of knowledge on actual childcare utilization also leads to small estimates because individual preferences in favor of or against early childcare remain unrevealed. Third, papers do not agree regarding the question whether childcare mainly affects the intensive or the extensive margin of employment, e.g., compare Carta and Rizzica (2018) to Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015), Bick (2016), and Felfe et al. (2016). Fourth, previous studies show some transmission channels that drive or attenuate labor supply effects. If the expansion of public childcare supply crowds out private childcare, effects on labor supply can be limited (Felfe and Lalive 2012; Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas 2015). Furthermore, heterogeneities regarding mother’s age, the number of children, and household composition reveal the broad range of estimates with respect to socioeconomic characteristics (Carta and Rizzica 2018; Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas 2015). Those findings are confirmed by papers using structural models and simulations, where the introduction of legal claim to a childcare slot or the increase of childcare coverage are simulated within a theoretical framework that models decisions of individuals or households (see Panel C of Table 1).Footnote 4

Yamaguchi et al. (2018) contributes to our collection of quasi-experimental studies from Europe. The authors apply the MTE framework to a institutional childcare setting similar to our context. In Japan, parents unable to mind their children (single and disabled parents, parents working full time) are prioritized regarding the assignment of public childcare slots, which produces selection into treatment based on observable characteristics. Following this mechanism, their estimates show that mothers who increase their labor supply the most are those with the lowest probability of using public childcare. In this paper, we provide new evidence on the effects of the supply of early public childcare on the labor market participation of mothers. To tackle the endogeneity of labor market decisions and the selectivity of demanding external childcare, we exploit quasi-experimental expansion of early public childcare in Germany since 2005. So far, we have merely gained knowledge on the labor market effect on the average. In accordance with prior research, we identify a small and weak local average treatment effect (LATE) within the typical IV framework and then proceed to estimate marginal treatment effects (MTE) along the distribution of observables and unobservables that drive individual treatment decisions. Applying the design of MTE reveals transmission channels of this small ATE and uncovers substantial heterogeneity in marginal returns to the German childcare reforms.

The application of MTE in the context of childcare and parental employment is justified by several reasons. The application of MTE is suitable when the effect of a treatment is highly heterogeneous and varies due to correlation with unobserved characteristics (Brave and Walstrum 2014). Moreover, the relationship between unobservable characteristics and the outcome should follow economic theory. Both conditions apply to our research question. First, the assignment of childcare slots is selective and depends on relationship status and pre-birth employment status as defined by German law (see Section 2), which produces heterogeneous effects regarding observables. However, the access to information regarding juridical claims to a slot and unobservable characteristics such as the attitude toward external childcare and labor market attachment of women make the treatment effect to vary due to correlation between treatment status and unobservables. Due to this selection pattern, accounting for the difference between the ATE, the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), and the average treatment effect on the untreated (ATU) is important, which is feasible by applying MTE. Second, the theoretical trade-off discussed by Ermisch (1989) and Apps and Rees (2004) can be modeled suitably in the MTE setting. At the point of indifferences between sending the child to a public slot, the costs of external childcare (e.g., less time spent with children) and the benefits (forgone earnings and reduced depreciation of human capital during shorter time-out from the labor market) equal.

We provide three major contributions: First, to our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to analyze labor market effects with a focus on childcare for children under the age of three (to the best of our knowledge Brilli et al. 2016; Yamaguchi et al. 2018; are the two exceptions). Although the effects for children’s development from early childcare are well studied by Felfe and Lalive (2012, 2018), the effects on parental labor supply are left to be examined for Germany. By focusing on this age group, we take advantage of an institutional setting where slots are indeed scarce, so that the selection into treatment is limited and can be governed by market designers concerning observable characteristics. Although Yamaguchi et al. (2018) also consider care for children under the age of three and the Japanese setting shares some common features in the institutional setting, our setting is characterized by important differences. The childcare expansion exploited by Yamaguchi et al. (2018) amounts to twelve percent during a period of 10 years with an initial childcare coverage of about 27 percent. On the contrary, we focus on policy reforms that increased childcare coverage from almost zero to about 24 percent during ten years. In contrast to Brilli et al. (2016), this makes it possible to exploit both spatial and temporal variation in childcare coverage. The second difference is the German population, which is more heterogeneous than the Japanese regarding ethnic origin, attitudes toward external childcare, and further socioeconomic characteristics.

Second, we closely examine selection into different childcare arrangements and demonstrate that the expansion of early public childcare indeed raises the utilization of public childcare. Simultaneously, the expansion of public childcare, however, partially crowds out the demand for private childcare. Next to pure descriptive statistics on this topic by Havnes and Mogstad (2011), Givord and Marbot (2015), and Carta and Rizzica (2018), only Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas (2015) and Felfe and Lalive (2012) examined the effect of crowding-out in a more detailed way. However, Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas (2015) do not find any evidence of this effect and Felfe and Lalive (2012) only consider it in the context of childrens’ development.Footnote 5

Third, to examine which groups draw benefits from the reform, we estimate marginal returns along the distribution of observables and unobservables that determine the selection into treatment. This approach is particularly informative for policy conclusions. In contrast to only estimating the LATE, as would be the case in the standard IV setting, the MTE approach enables us to elaborate effect heterogeneity across the entire population under study, allowing a complete cost-benefit analysis. For instance, MTE helps to uncover whether certain groups without financial resources for private childcare gain from policy reforms. This approach aims to indicate whether the small average of employment effects is the result of a large range of estimates or whether the effect is homogeneously small for the entire distribution of the population.

We find that the utilization of early public childcare significantly increases the probability to work full time by 13.2 pp. Migrant mothers from another country of the European Union (EU) increase their employment probability at the extensive margin above average, while non-Union migrants do not increase labor supply. Regarding the selection process, we detect reverse selection on gains at the intensive margin. Effects on full-time employment are highly heterogeneous, whereas the utilization of public childcare increases the full-time employment probability of mothers with medium desire to early public childcare by at least 50 pp. Further examinations highlight that the employment effects from childcare are mainly driven by mothers who shift from part-time jobs to working full time. Thus, effects are mainly driven along the intensive margin which reasons that the effects on general employment are barely found. There are only a small fraction of mothers with low distaste for public childcare who shift from non-employment to (part-time) employment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the institutional setting and formulates econometric challenges that have to be taken into account in the research design. After Section 3 presents the empirical strategy, justification of applying the MTE framework and data, Sections 4 and 5 provide the results. In Section 6, we draw policy implications from our estimated results.

2 Institutional background

In Germany, the gap between general female employment and the employment of mothers having children under the age of three is one of the largest across the OECD. The limited availability of public childcare hampers mothers aiming to return to the labor market shortly after childbearing. While the employment gap between mothers with a child aged 6–14 and mothers with a child aged 0–2 is on average 19.8 percentage points in the OECD, this distance is approximately 26.2 pp in Germany. Figure 1 illustrates that this gap is fairly low for countries where public spending on childcare is generous, such as in Denmark and the Netherlands.Footnote 6

Since the introduction of a legal claim to a slot for children aged three to six in 1996 (Child and Adolescent Support Law [Kinder- und Jugendhilfegesetz, KJHG]), the childcare supply for this age group has almost reached universal coverage (see BMFSFJ 2017). The low labor market participation of mothers having very young children legitimated the promotion of childcare for children under the age of three. Since the mid-2000s, several bills have promoted its expansion in West Germany: After the Day Care Expansion Law (Tagesbetreuungsausbaugesetz, TAG) was enacted in 2005, a law which targeted coverage of early public childcare in West Germany of 17 percent until 2010, a common conference by the German government, municipalities, and towns increased this target in 2007 to a 35 percent coverage. Since October 2010, the Law on Support for Children (Kinderförderungsgesetz, KiföG) has promised a legal claim to a (part-time) slot for children aged one and above to lone parents, or if both parents were employed before birth, on job searches or obtaining unemployment assistance (§24 I 2 Sozialgesetzbuch VIII), or if a child’s sibling is or has been already in public care (Bick 2016; Felfe and Lalive 2012, 2018). This legal claim became universal in 2013 to all parents. Thus, policy prioritizes parents who are more in need of childcare.

Although the explicit prioritization of lone parents and employed couples was established by law in 2010, this prioritization has already been implicitly practiced before. Before 2010, public childcare slots were assigned due to the first-come-first-serve concept with exclusions for employed (regarding the time before birth) and lone parents (Bien et al. 2006; Felfe and Lalive 2012, 2018). Following this, we define relationship and pre-birth employment as the two major variables of treatment assignment. Based on those priority rules and finding by Yamaguchi et al. (2018), we expect that parents employed before birth and lone parents have the largest likelihood of using public childcare, but show low employment effects from the childcare reforms. The reason is that before the childcare reforms were in force, such groups with a high labor market attachment used private childcare arrangements or used the low supply of public childcare already available before 2005. Thus, we expect that labor supply effects are detectable for parents who did not use private childcare before and have a medium and low labor market attachment and thus, a medium and low probability of using pubic childcare.

The expansion of early public childcare for children under the age of three in West Germany provides several advantages, which we use to establish causal interpretation: First, the quasi-experimental expansion of childcare starting in 2005, is of a great extent and increased coverage from virtual non-existence before 2005 to 23.6 slots per 100 children in 2015 (see Fig. 2). Additionally, the expansion occurred over a short time horizon, which gave little time for endogenous residency choices that may distort the identification of causality. Second, by considering childcare for children under the age of three, we expect a significant effect of the childcare availability on maternal labor supply because the time distance between the decision to bear a child and the decision to demand external childcare is short. Third, public childcare is a homogeneous good characterized by high quality standards, which has hampered the emergence of a private childcare market (Bauernschuster et al. 2016). Quality standards, set by the federal states, regulate opening hours, group sizes, staff-child ratios, and staff qualifications (Busse and Gathmann 2018; Felfe and Lalive 2012). Fourth, the institutional environment and other instruments of family policy were rather constant during our observation period. One exception is the parental leave reform in 2007, which replaced a means-tested system that paid a maximum of 300 euros monthly for up to 24 months or 450 euros for up to 12 months by a new system. After 2007, the amount depends on average net income in the last 12 months before childbirth, while the regular eligibility duration is 12 months (for more details, see Raute 2019). In Section 4.2, we demonstrate that this shift in the institutional environment does not affect our results.

The description of the institutional setting outlines two important econometric issues embodied in the empirical analysis: First, the scarcity of slots for children under the age of three enables policy to explicitly define observable features that are prioritized when assigning childcare slots. Lone parents and couples where each parent is employed before birth are privileged. This procedure produces selection on observables and defines relationship status and pre-birth employment status as the two central assignment variables. Second, despite this deterministic matching procedure, selection on unobservables is important to account for. The access to information (information channel), for instance, regarding juridical claims to receive a free slot or knowledge about how to skip ahead in the waiting list, inter alia, determines the use of public childcare and its effects on the maternal labor supply. Hence, unobservable characteristics presumably affect the outcome differently depending on treatment status.

3 Empirical strategy

3.1 Identification strategy

When estimating the effect of childcare utilization on maternal labor supply Yit, three major econometric issues arise from applying OLS:

First, the treatment regarding whether to send the child to an external public slot (Dit = 1) or not (Dit = 0) suffers under selection. Second, the treatment status is simultaneously determined with general labor market attachment and career orientation and correlates with the education of the mother and unobservables. Thus, even if the covariates Xit include a large set of socioeconomic variables, γ will be upward biased when using OLS.

We take advantage of the large-scale expansion in slots for children under the age of three initiated in 2005 which produces exogenous variation between municipalities and across time. To estimate an ATE, we apply a two-stage IV procedure, where we implement a difference-in-differences estimator into the first stage. In Eq. (2), public childcare utilization Dit is explained by childcare coverage Coveragekt in municipality k where mother i lives and by its interaction with the time dummy Postt, which refers to survey years since 2005. Thus, δ2 is the parameter of interest in the first stage and gives to what extent the German childcare reforms increased individual utilization of public slots:

The expositions on the institutional background illustrate that municipalities predict the demand for childcare concerning indicators of the demand for childcare, such as female employment rate, birth rates, and the economic structure in municipalities. Thus, spatial variables Ckt are added to Eq. (2) so that the set of instruments \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) contains (Coveragekt, Coveragekt*Postt, Ckt). Finally, by inserting predicted childcare utilization \({\widehat{D}}_{it}\) into Eq. (1), γ gives the effect of childcare utilization on maternal labor market participation.

To ensure that γ allows causal inference, the expansion of childcare coverage needs to be unrelated to individual labor supply preferences and further individual characteristics. This exogeneity is established by the process complexity of opening new facilities. Explanations by Felfe and Lalive (2012) which are based on Riedel et al. (2005) and Huesken (2010), illustrate that having the mandate of setting quality standards in federal states’ responsibility, results in a large variation between the federal states in opening hours, child-staff ratio, and childcare coverages. However, there also appears to be significant heterogeneity in childcare growth between municipalities within a given federal state. While local administrations predict the demand for childcare concerning local characteristics, such as birth rate and female employment rate, non-profit organizations propose opening new facilities. However, ultimately, the federal state is responsible for evaluating these proposals and allocating public subsidies so that it is unsure until the end regarding whether a childcare provider receives public funds and the right to open a new facility. Next to this precarious situation for the potential childcare provider, spatial heterogeneities in the supply of childcare slots arise from non-predictable supply shocks and factors that are exogenously distributed, such as knowledge about the funding system, scarcity of qualified staff, and constraints in caring space (see Felfe and Lalive 2012, 2018). These facts establish the exogeneity of childcare expansion. This setting produces great heterogeneities in childcare expansion both between federal states and between municipalities within a given federal state. By having a focus on childcare for children under the age of three, we take advantage of the fact that initial coverage is almost zero before the underlying reforms and slots are very scarce, resulting in considerable excess demand (Wrohlich 2008) so that market designers can govern the assignment of slots concerning observable characteristics. This an important advantage compared to similar approaches when childcare for older children is analyzed with pre-reform coverage of some substantial level.

Remarks by Bauernschuster et al. (2016) and Cornelissen et al. (2018), illustrate that the childcare reforms have not crowded out other public expenditures and funds of other instruments of family policy. Income taxes are set at the federal level, and social and unemployment benefits are also regulated at this level; therefore, they do not depend on local government finances. Furthermore, fees for childcare slots are relatively constant (see also Haan and Wrohlich 2011) while Rhineland-Palatinate is the lone federal state which introduced free daycare for two-year-olds during the observation period (Busse and Gathmann 2018).

Up to this point, we have argued that γ estimates the causal ATE of public childcare utilization on maternal employment. Although this is a reasonable procedure, it does however, only present a local average treatment effect (LATE). This circumstance is unsatisfying because the range of estimates is presumably rather large (Blau 2000) and depends on the socioeconomic characteristics of mothers.

This third problem is related to the another issue: The matching procedure formulated by the Day Care Expansion Law defines a group of targets which are aimed to be prioritized when it comes to assigning the scarce slots. This group comprises lone parents, couples where both parents are full-time employed before birth, and if older siblings of the youngest child are already assigned. This procedure produces selection on observables. Additionally, the first-come-first-serve procedure leads to selection on unobservables where mothers with a high desire to participate in the labor market, and with greater access to information about this procedure, are more likely to be selected into treatment Dit. In the following section, we present the approach of marginal treatment effects (MTE) to tackle the second and third issues.

3.2 Uncovering unobservable heterogeneities

Statements in Section 1 introduced the justification of using MTE in the context of maternal employment and public childcare. The large heterogeneity in the treatment effect, the correlation between treatment status and unobservable characteristics, and the necessity to differ between ATE, ATT, and ATU due to selection are main reasons that legitimate the use of MTE. The use of MTE uncovers effect heterogeneity across the entire population under study and enables to derive those effects from the selection pattern and the unobserved resistance toward childcare utilization. Furthermore, a clear relationship between economic theory and the MTE setting should apply. Based on theory by Ermisch (1989) and Apps and Rees (2004), the trade-off between the costs of external childcare (e.g., less time spent with children) and the benefits (forgone earnings and reduced depreciation of human capital during shorter time-out from the labor market) decide whether to participate at the labor market or not. The following elaborations explain how this trade-off is modeled within the MTE framework. Note that an alternative to account for heterogeneous effects are statified estimates for socio-economic subgroups such as Carta and Rizzica (2018) present. We also provide such stratifications in Section 4.2. However, such subgroups are defined by observable variables but the institutional setting outlined that unobservable characteristics such as the information channel are a significant source of heterogeneity in our case. Furthermore, heterogeneities also exist within subgroups so that we can only presume the reasons for an above- or below-average effect for one group. The application of MTE overcome this issue because it summarizes confounding and enhancing characteristics in unobserved resistance toward childcare utilization.

The empirical setting of estimating marginal treatment effects builds on the discussions of Heckman and Vytlacil (1999, 2005), Heckman et al. (2006), and Carneiro et al. (2011). Although Björklund and Moffitt (1987) first developed MTE to evaluate selective labor market programs, applications in the context of labor supply are rare.

The starting point here is the potential outcome model where we define two potential outcomes Yj (j = 0, 1). Y1 denotes the labor supply of a mother with public childcare utilization (D = 1) and Y0 gives labor supply without treatment (D = 0):Footnote 7

In the case of selection, the link between individual characteristics, such as education of mothers, and their labor supply (β1, β0) depends on the treatment status (see also Felfe and Lalive (2018)). Additionally, the potential outcome depends on an unobservable part of the outcome (U1, U0), which also may differ for whether the mother receives the treatment or not. Thus, the outcome (Y1, Y0) may be different for mothers even with the same observed characteristics as long as their unobservables U1 and U0 attain different values. Due to the selection on observables Z and unobservables V into the treatment, we can capture D* as the latent desire regarding whether to send the child to a public caring slot under the age of three:

In the framework of this index function model, Z contains observables characteristics Xit and spatial variables \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) that reflect the temporal and spatial variation in the supply of childcare (Coveragekt, Coveragekt*Postt) and further spatial variables Ckt. Unobservables V reflect distaste in using public childcare. A larger value of V implies higher resistance, which decreases the probability of demanding public childcare. Relying on previous exposition, it seems reasonable to assume that \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) is unrelated to individual characteristics Xit and the potential outcome (Y1, Y0). Moreover, conditional on Xit, \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) has to be unrelated to the unobserved parts (U1, U0) and only affects labor supply through the channel of D*.

Following our expositions, we denote the probability of utilizing public childcare as the propensity score \(P({Z}^{\prime}\delta )=p\), which is a continuous function \(F({Z}^{\prime}\delta )\) ranging from 0 to 1. To better conceive selection into treatment concerning observables and unobservables, we assume V also to be a continuous function described by a cumulative distributional function (c.d.f.) F(V) with percentiles UD and uniform distribution. Relying on Eq. (7), we can formulate the point of indifference regarding whether to select into the treatment or not:

This is the point where the probability of utilizing public childcare \(F(Z^{\prime} \delta )\) equals its resistance F(V), so that the observable selection helps to reveal an unobservable preference for public childcare. Recall Section 2, where we have defined relationship and pre-birth employment status as the two major variables of treatment assignment. Imagine a mother with a low propensity score p because she does not meet one of the two conditions and lives in a municipality characterized by low childcare supply. Thus, if this mother selects into the treatment at a low level of p, she reveals a high unobservable preference for utilizing public childcare. On the contrary, lone mothers who were employed before birth are assigned with a large level of V, if they have a general unobserved resistance toward public childcare for children at such early stages in life. Thus, if we smoothly increase childcare coverage while fixing X, all mothers will gradually select into the treatment, and thus, reveal their rank in the distribution of unobservables and uncover their willingness-to-pay parameter. In line with the theoretical groundwork, we can state the following trade-off: At the point of indifference \(MTE({X}_{i}=x,{U}_{{D}_{i}}=p)\), the costs and the benefits of treatment are equal.

Taking the expectation operator on Eq. (6), we can formulate the expectation of Y conditional on the set of covariates X and the propensity score p, while deriving E(Y∣X, p) regarding p, yielding the marginal treatment effect.Footnote 8

Because a small supply of childcare was already available before 2005 for those with the highest desire to have access to a slot, we expect that those with median and higher resistance now gain from an expansion that shifts coverage from a small to a more generous level because those with highest desire to work utilize one of the few slots or demand private childcare before the reforms. Following this, we expect a reverse selection on gains producing an MTE curve with a positive slope along unobservable resistance toward public caring slots.

The framework of MTE can be estimated in a two-stage procedure: To conceive the pattern of selecting into treatment, we run probit estimations for the selection equation displayed in Eq. (7) and regress Dit on socioeconomic covariates Xit and instruments \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\). This design also allows us to examine whether the childcare reforms crowds out the utilization of alternative childcare forms. To estimate the outcome equation displayed in Eq. (11) we apply OLS and regress some indicator of labor supply of mothers on socioeconomic variables Xit and interactions between Xit and the propensity score p. Consistent with Felfe and Lalive (2018), we choose a third-order polynomial degree in the propensity score. Although Felfe and Lalive (2018) consider a fairly different outcome (children’s skills), a comparison of the first stage between Felfe and Lalive (2018) and our paper is senseful because they use the same childcare reforms. While Felfe and Lalive (2018) estimate linear probability model, we choose probit estimation in order to model probabilities of using public and private care arrangements more suitably. Moreover, a relevant difference is the operationalization of the public childcare supply. While we use childcare coverage within a differences-in-difference framework to study crowding-out effects of private childcare, Felfe and Lalive (2018) use a set of 318 interaction terms between district-specific post-expansion periods and the respective municipalities. The main reason for our choice is the simpler interpretation of our first stage. Furthermore, using childcare coverage in order to operationalize the supply of childcare is common in literature (e.g., Cornelissen et al. 2018; Felfe et al. 2016; Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas 2015). Regarding the second stage, one difference is that Felfe and Lalive (2018) apply non-parametric estimations, while we apply parametric estimations.Footnote 9

3.3 Data

To study the impact of childcare expansion since 2005 on the labor market participation of mothers, representative survey data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) is linked with spatial data from the Statistical Offices of the German federal States. If we consider mothers with at least one child aged one or two, we obtain 4,057 observations on 2,841 mothers from 321 municipalities from West Germany so that 98.5 percent of municipalities in West Germany are covered. Merging spatial data to individual level data, which is restricted to mothers with young children, involves the danger that the final sample is selective and that the final sample and the spatial data at the municipality level are not comparable regarding childcare supply. However, despite some minor deviations, Fig. A.1 in Appendix A indicates that the final sample is comparable to spatial data at the municipality level regarding childcare coverage.

The use of SOEP data for 1998–2015 is legitimated by four reasons that are highly relevant for exact identification of labor market effects:Footnote 10 First, we study the effects of childcare on a battery of outcomes, covering current employment and the ratio of pre- and post-birth earnings to approximate the depreciation of human capital during a time-out from the labor market. This approach highlights the need to use longitudinal panel data giving current and past labor market performance.

Second, to strengthen our identification strategy, we also examine whether childcare expansion triggers internal migration patterns. In the SOEP data, we can identify whether persons move from one year to another at the level of municipalities. Third, SOEP data allows capturing the language skills and ethnic origin of migrants and identifies whether migrants leave Germany again or not. Fourth, SOEP data results in a sufficient large number of observations, which is important in the framework of MTE.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive evidence

Table 2 provides an overview of the socioeconomic characteristics of lone parents, mothers in continuous relationships, and their partners. If we differentiate by the utilization of early public childcare in Columns 2–4, positive selection into the treatment is observable regarding education and pre-birth employment. Columns 5–7 display individual characteristics by expansion speed. Mothers are assigned to the group above-median if they live in a municipality where growth in childcare coverage is at least above median growth (~11.3 pp) during the central expansion period of 2002–2010. Again significant differences appear.

One reason for a small average labor market effect is the presumption that the increase in the supply of public childcare crowds out private childcare–be it formal or informal. Following Hank and Kreyenfeld (2004), Baker et al. (2008), and Busse and Gathmann (2018), we differentiate three different kinds of childcare: 1) public, 2) private and formal, and 3) private and informal. Private and formal arrangements include caring services from nannies or other official caring staff. The term informal refers to cases when relatives, friends, and acquaintances mind.

The left-hand graph of Fig. 3 illustrates that the childcare reforms increases utilization of public childcare, while in the pre-reform period (1998–2005), this share is fairly constant.Footnote 11 Simultaneously, the share of private childcare (informal and formal aggregated) decreases so that in 2015, the share of both public childcare and private childcare is approximately the same. Regarding labor supply of mothers as our main outcome variable in the right-hand graph, a positive development for labor market participation is detectable at the extensive margin, while the share of full-time employed mothers remains constant below ten percent. This latter remark may raise doubts regarding whether the childcare reforms indeed increase the employment of mothers. The question of whether the decrease in the utilization of private childcare crowds out potential employment effects from increased utilization of public childcare is left to be examined. Table 3 presents indicators used to measure maternal employment and the depreciation of human capital during a time-out. If hourly wage is supposed to approximate productivity, first, hourly re-entry wage as the first observed wage after time-out and second, the ratio between re-entry wage and pre-birth wage are chosen as two reliable indicators (see also Carta and Rizzica 2018; Lalive et al. 2014; Lalive and Zweimüller 2009). Given a constant level of the pre-birth wage, the latter would increase from less depreciation in human capital. Additionally, Panel B gives a descriptive summary of early public childcare coverage and further spatial variables that characterize the economic and demographic composition of municipalities. Those variables come from the Statistical Offices of the German Federal States and are merged to SOEP data by having information about the individual residency at the level of municipalities. Childcare coverage is available for the years 1998, 2002, and 2006–2015 and gives the share of children under the age of three who are minded in public childcare slots.

Trends in childcare utilization and labor supply of mothers (in percent). a Childcare Utilization. b Maternal Labor Supply. Note: The left-hand figure shows trends in the utilization of childcare calculated at the individual level from SOEP data. Besides public childcare, private formal and private informal arrangements are distinguished. Private formal arrangements include caring services from nannies or other official caring staff and informal care refers to cases when relatives, friends, and acquaintances are minders. The graph Private is the aggregate of both forms of private childcare. The right-hand graph shows trends in the share of working mothers concerning the intensity of employment. Again, these shares are calculated at the individual level based on survey data. Source: SOEP; own illustration

Having spatial data enables to test the common trend assumption. The maternal labor supply should have evolved similarly if the childcare reforms had never been executed. To facilitate understanding without a loss of information, we split our sample into municipalities that increased childcare coverage during the central expansion period 2002–2010 above or below median growth, while median growth is approximately 11.3 percentage points. In Fig. 4, municipalities with above-median growth clearly display higher birth rate, higher female employment rate, higher voter share of conservative parties, and better economic conditions. However, level differences appear to be fairly constant. Note also that spatial numbers on childcare coverage and female employment rate from Fig. 4 are very comparable to childcare utilization and employment share displayed in Fig. 3.

Common trends in childcare coverage and spatial characteristics. Notes: Figure 4 compares spatial characteristics by expansion status. Mothers are assigned to the group above-median if they live in a municipality where growth in childcare coverage is at least above median growth (~11.3 pp) in West Germany during the central expansion period of 2002–2010. The two upper graphs give public childcare coverage for children under the age of three and employment rate of females aged 15–64 measured at the level of municipalities. The second row displays trends in birth rate and conservatism over time, while the latter is approximated by the conservative vote share at the last parliamentary election. Birth rates are approximated by the number of births per 1000 women. These two variables are included as control variables in our analyses. The two lower graphs give two indicators of the general economic development in municipalities, namely unemployment rate and GDP per employed person. Because those variables are captured only since 2002 and 2000, they are omitted from the empirical analyses. However, robustness checks, not presented in this paper, demonstrate that including those two spatial variables does not affect our results. Source: Statistical Offices of the German Federal States; Statistical Office of the Federal Employment Agency

4.2 Instrumental variable estimations

In Columns 1–4 of Table 4, OLS estimates of Eq. (1) reveal a clear significant employment impact from utilizing public childcare. After gradually adding socioeconomic covariates, federal state dummies, and children’s characteristics, public childcare utilization increases both the probability to work full time and of having a part-time job. If we instrument childcare utilization Dit by temporal and spatial variation in childcare coverage and further spatial characteristics \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\), first-stage results show increased utilization of public clots. In the full model (Model 8), an increase in childcare coverage of ten percentage points, increases the probability to demand a public childcare slot by 23.8 pp.Footnote 12 After adding children’s characteristics, such as the number of older children or the sex of the youngest, the mother’s employment probability is no longer significantly affected. This result hints at the important role of household composition. Besides the insignificance of point estimates of employment and part-time employment, this finding confirms expectations outlined in Section 3, whereas OLS overestimates γ due to self-selection and endogeneity of the treatment. However, utilization of public childcare still significantly impacts the probability of the mother being full-time employed by 13.2 pp. The mother’s full-time employment probability increases by 1.3 percentage points if childcare coverage is increased by ten percentage points.Footnote 13

Thus, employment effects seem to be small and appear to be driven along the intensive margin. However, to examine whether this is simply the result of averaging a broad range of big and small point estimates is still to be examined. The parental leave reform in 2007 does not affect our results. According to Bauernschuster et al. (2016) and Raute (2019), highly educated mothers with above-median earnings are defined as the treatment group so that adding an interaction term between being highly educated and the time dummy Post 2007 that refers to survey years since 2007 controls for the impact of this institutional shift. This robustness check slightly increases the effect of the childcare reforms on the probability of full-time employment from 13.2 pp in Table 4 by 0.5 pp.Footnote 14 Next to parental leave benefits, the second element of maternity leave is job protection of mothers, which can last up to 36 months (Raute 2019). Despite the generous job protection, the limited duration of parental leave benefits creates large incentives to return to work twelve months after birth. Only 6 percent of mothers with a child aged one are in maternity leave. If we exclude this small group from Model 8 of Table 4, the IV estimate declines sparsely to 0.130.

Table 5 stratifies IV estimations concerning some particular socioeconomic groups. Using public childcare considerably increases the employment probability of lone parents by 57.4 pp.Footnote 15 Similarly, migrants from EU countries increase their employment at the extensive margin above average, but also their utilization for public slots. On the contrary, married mothers and medium and highly educated mothersFootnote 16 increase only the intensity of work by a larger effect than the average displayed in Table 4, while non-Union migrants do not increase employment at all. Again, the household composition strongly impacts our estimation results. While no employment effects are found for mothers having only one child (under the age of three), mothers with children under the age of three and at least one further child aged at least three years increase both their employment probability and their working intensity. This result may be explained by the conditional legal claim introduced in 2010 prioritizing children that have siblings already in childcare. However, the information channel is also an explanation because parents of older children have already collected experience in combining parenthood and work and with the first-come-first-serve procedure in childcare facilities. Table 5 reveal what the small ATE displayed in Table 4 cannot uncover: Certain groups benefit greatly from the expansion of public childcare. However, they benefit differently—along the intensive margin or exclusively at the extensive margin or both.

Socioeconomic characteristics, such as relationship status and ethnic origin confound or enhance estimated treatment effects. The composition of one subgroup concerning those characteristics is important to note so that we can only presume the reasons for an over- or below-average effect for one group. Additionally, heterogeneities within subgroups may be ignored. One method to overcome this issue is the application of MTE, where confounding and enhancing characteristics are summarized in unobserved resistance toward childcare utilization and the propensity score. This strategy is essential to answer the following open questions:

-

Which patterns of treatment selection are observable? Does the expansion of the supply of public childcare shape self-selection?

-

Does the expansion of public childcare crowd out private childcare?

-

Which groups benefit the most from better options of combining parenthood and work? Which deciles of the distribution of resistance to treatment react due to the increase of public childcare supply?

-

Does the increase in full-time employment from the German childcare reforms coincide with a symmetric decrease in the probability of part-time jobs?

5 Uncovering observable and unobservable heterogeneities

5.1 Crowding-out of private care arrangements

To uncover transmission channels of the small ATE found in the previous section, we begin to reveal answers regarding the first two questions just raised:

-

Which patterns of treatment selection are observable? Does the expansion of the supply of public childcare shape self-selection?

-

Does the expansion of public childcare crowd out private childcare?

Therefore, we more closely examine the first stage formulated in Eq. (2) by allowing for alternative childcare arrangements. First, Model 1 of Table 6 again demonstrates that the expansion of early public childcare coverage increases the probability of utilizing public childcare. Likewise, the initiation of those policy reforms makes the utilization of private childcare less attractive. Following a ten-percentage-point increase in the supply of public childcare, demanding informal childcare becomes 21.5 pp less likely and the probability of demanding private formal childcare is decreased by 14.3 pp. If private formal and private informal care are captured as one category, probit estimations indicate a decrease of private care by 32.1 pp, a result which exceeds the increase in the probability of utilizing public childcare.Footnote 17 Because we only estimate probabilities and average effects, we can conclude that private childcare arrangements are at least partially crowded out and substituted by public childcare slots. Estimations in Columns 4–6 stratified on mothers who demand any form of care show that effects are mainly driven by crowding-out of private formal care. Thus, mothers who shift from private childcare to a public caring slot, weaken potential employment effects and are one reason for the small magnitude of the estimated ATE.

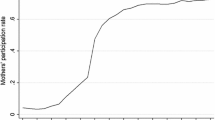

A brief look at the distribution of the propensity score obtained from Model 1 of Table 6 highlights some strengths of our econometric setting. Figure 5 illustrates that the propensity score of treatment mothers that utilize public childcare and the score of control mothers cover a large range of distribution from zero to 80.7 percent. This variation is induced both by variation in \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) and by the covariates. However, large variation in the propensity score ranging from 1.4 to 60.9 percent is also solely induced by variation in \({\widetilde{Z}}_{kt}\) without conditioning on covariates. This result re-emphasizes the high relevance of the instrument and enables identification of marginal returns along a broad range of childcare coverage.

Propensity score by treatment status. Note: The figure gives the density of the propensity score by treatment status whereas mothers that utilize public childcare in year t (Dit = 1) are assigned to the treatment group. The calculation of propensity score is based on probit estimations of the first stage (Eq. (2)). In the first stage, the treatment dummy Dit is regressed on childcare coverage, on the interaction between coverage and the post-period time dummy Postt, dummies for survey years, dummies for federal states, further spatial characteristics given in Table 3, and covariates summarized in Table 2. Source: SOEP; Statistical Offices of the German Federal States; Statistical Office of the Federal Employment Agency; own illustration

Further determinants of childcare utilization in Table 6 illustrate some interesting findings. Again the household composition, education and ethnic origin matter. One interesting finding is that foreigners are more likely to utilize public childcare and are less likely to use informal childcare. However, this finding is mainly attributable to mothers from other EU countries. According to Eqs. (4)–(6), such selection patterns are likely to affect the labor supply (Y1, Y0) differently, depending on treatment status. Additionally, unobservable resistance toward sending an own child to an external childcare facility under the age of three affects the outcome differently by treatment status. This legitimates the application of marginal treatment returns.

5.2 Marginal returns to early public childcare

From the results of Section 5.1, we conclude that at least partial crowding-out of private childcare utilization is one reason why only a small employment effect on average is found. In this section, we examine heterogeneities to indicate whether the small ATE is the result of a large range of estimates or whether it is homogeneously small for the entire distribution of the population:

-

Which groups benefit the most from better options of combining parenthood and work? Which deciles of the distribution of resistance to treatment react due to the increase of public childcare supply?

-

Does the increase in full-time employment from the German childcare reforms coincide with a symmetric decrease in the probability of part-time jobs?

In Fig. 6, effects obtained from estimating Eq. (11) are plotted against the percentiles of unobserved resistance F(V) denoted as UD for sample means of covariates. A larger value of UD refers to higher resistance against the treatment. At the extensive margin, the MTE curve illustrates that for the majority of distribution, no employment effects occur. However, those with a low resistance of UD from 0.18 to 0.3 gain from the availability of public childcare with an employment effect of below 50 percentage points. Panel b draws a clearer image. Marginal benefits increase with resistance so that mothers who are most likely to enroll concerning observable characteristics do not benefit regarding labor supply. This finding uncovers reverse selection on gains. Mothers with medium resistance of UD from 0.35 to 0.75 increase their full-time employment probability sizably. Because of uniform distribution for F(V) this refers to a large share of about 40 percent of the sample population who increases the probability to work full time by at least 50 pp up to 100 pp. Hence, the small ATE for full-time employment of 13.2 pp presented in Table 4 is just the average of highly heterogeneous effects. A comparison of Panels b and c uncovers that employment effects are driven by mothers with medium resistance that shift from part-time to full-time work. Mothers with medium and high resistance (UD > 0.55) decrease their part-time employment probability. Thus, effects are mainly driven along the intensive margin. The substitution of part-time work by full-time occupations also explains why Panel a does not indicate employment effects at the extensive margin. However, the MTE curve for part-time employment suggests that a low share of mothers with the lowest resistance increase their probability of being part-time employed. This range is congruent with that range in Panel a, with low resistance that increases their general employment.

Marginal returns to early public childcare. a Employment. b Full-Time Employment. c Part-Time Employment. Note: Figure 6 displays the MTE curve for the three indicators of maternal labor supply (employment, full-time and part-time employment) based on the first-stage in Eq. (2) and the outcome Eq. (11) (for tabular presentation, see Table B.1 of Appendix B). The first-stage applies probit estimations and regresses the utilization of public childcare (Dit = 1) on spatial characteristics given in Table 3, dummies for survey years, dummies for federal states, and covariates summarized in Table 2. The outcome equation based on OLS also controls on time dummies, federal state dummies, and variables given in Table 2 and estimates a third-order polynomial degree by parametric estimation. Bootstrapped standard errors with 50 replications are clustered at the individual level. The graphs respectively plots marginal returns from utilizing public childcare on resistance UD for sample means of covariates. Source: SOEP; Statistical Offices of the German Federal States; Statistical Office of the Federal Employment Agency; own illustration

Figure B.3 in Appendix B examines the depreciation of human capital during time-out and the effects of childcare expansion on fathers’ labor supply as two further transmission channels. First, the effects on the hourly re-entry wage indicate some hints at the fact that human capital depreciation is reduced by utilizing childcare for mothers with a low resistance toward public childcare. However, effects are not robust for the ratio of the pre-birth wage and the re-entry wage. Second, couples react with an intrahousehold shift of work. While mothers mainly shift from part- to full-time employment in consequence of the better availability of childcare, partners show a reverse pattern but of less extent.

The estimation of marginal treatment effects offers a more comprehensive picture on employment effects from public childcare. First, a small fraction of mothers with low resistance (0.18 < UD < 0.30) increase their employment probability. Those mothers seem to shift from non-employment to part-time employment. Second, the effects on full-time employment are highly heterogeneous, whereas the utilization of public childcare increases the full-time employment probability of mothers with medium resistance (0.35 < UD < 0.75) by at least 50 percentage points. In accordance with Yamaguchi et al. (2018), this finding highlights the reverse selection on gains for full-time employment. Thus, as mothers with medium and high resistance also decrease their part-time employment probability, the employment effects from childcare are mainly driven by mothers who shift from part-time to working full time. Thus, the effects are mainly driven along the intensive margin. This is in accordance with previous research by Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015), Bick (2016), and Felfe et al. (2016) and explains why effects on general employment are barely found. Third, effects of labor supply are absent for those with the lowest resistance toward the treatment because mothers with the largest attachment to the labor market worked already before the child reforms because even before 2005, a low supply of public childcare and informal care arrangements were available (see also Yamaguchi et al. 2018). Thus, if childcare coverage is gradually expanded from a low level of supply, more mothers with a marginally higher resistance towards early public childcare slots select into the treatment and jobs.

5.3 Sensitivity analysis

Three important economic issues raise claims on the reliability of our results: First, municipalities with a large growth in childcare coverage may aim at attracting couples with a high desire to bear a child and a high pressure to combine parenthood or work. Ignoring the endogeneity of residency choices would lead to upward biases. Our panel data allows for following individuals across time and identify couples’ and lone parents’ moving patterns. Thus, we can separate analysis between mothers who move at least once from one municipality to another during the observation period (movers) and non-movers who stay in the same municipality. Panel a of Fig. 7 presents MTE curves for non-movers, which account for a share of 84.5 percent in our sample. Although the size of marginal returns to childcare is slightly weaker, the range of significance for mothers with medium resistance stays robust for both full- and part-time employment.Footnote 18

Internal migration, the definition of treatment, and the placebo test. a Exclusive Consideration of Non-Movers. b Alternative Definition of Treatment Status. c Placebo Test. Note: Figure 7 displays the MTE curve for full-time and part-time employment based on the first-stage in Eq. (2) and the outcome Eq. (11). The first-stage applies probit estimations and regresses the utilization of public childcare (Dit = 1) on spatial characteristics given in Table 3, dummies for survey years, dummies for federal states, and covariates summarized in Table 2. The outcome equation based on OLS also controls on time dummies, federal state dummies, and variables given in Table 2 and estimates a third-order polynomial degree by parametric estimation. Bootstrapped standard errors with 50 replications are clustered at the individual level. The graphs respectively plot marginal returns from utilizing public childcare on resistance UD for sample means of covariates. In Panel a, estimations are exclusively done for mothers who have not changed the municipality where they live. Panel b tries an alternative definition of the treatment status and assigns mothers only to the treatment group Dit = 1 if their children under the age of three attends public childcare at age one and two. Panel c models employment status before birth as the outcome. Source: SOEP; Statistical Offices of the German Federal States; Statistical Office of the Federal Employment Agency; own illustration

The second claim addresses the definition of treatment and the number of years a child attends public care (see Burger 2010; Busse and Gathmann 2018). If childcare utilization is continuous for years, mothers and fathers are not forced to irregularly interrupt their employment biographies, which potentially attenuates wage growth. Thus, it can be expected that parents benefit more whose child under the age of three continuously attend public childcare. Thus, we assign mothers to the treatment group only if their child attends a public slot at the age of one and two.

In Panel b of Fig. 7, the fraction of mothers gaining from public childcare concerning full-time employment is widened to mothers with low resistance down to UD = 0.1. This result reveals the importance of supplying continuous childcare. Permanent caring of children prevents breaks in mothers’ employment biographies and increases full-time participation of mothers.

Finally, Panel c applies a placebo test, where employment status before birth is modeled. As expected, confidence intervals envelope zero along the entire range of distribution. The same result is obtained if lagged employment status (by two years) is modeled (results are available upon request). Further analyses provided Fig. B.1 in Appendix B strengthens the independence of our results from econometric features of the chosen MTE setting.

Prior research suggests that the underlying childcare reforms may increase fertility (see Bauernschuster et al. 2016; Bick 2016; Haan and Wrohlich 2011). However, whether the supply of public childcare only affects the extensive margin of childbearing or whether it also affects the number of births is so far inconclusive. If we assume for the moment that the expansion of public childcare makes the probability to second and third birth transitions more likely, this would affect our results. Mothers with a high desire for further births in our sample would weaken the relationship between childcare and maternal employment. Because we model maternal employment one and two years after childbirth, fertility particularly affects our results if time to the next birth is short. If we exclude those 91 cases in our sample, in which a mother gave birth to a further child during having a child under the age of three, the IV estimate for full-time employment in Column 8 of Table 4 increases to a significant parameter of 0.150. Nevertheless the endogeneity between fertility and labor supply should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of this paper because earlier births also affect current labor supply and fertility. As Table 2 outlines a substantial share of mothers have children in kindergarten and school age.

6 Conclusion

In Germany, the gap between female employment and the employment of mothers having children under the age of three is one of the largest across the OECD. In this paper, we exploit quasi-experimental expansion of early public childcare in Germany since 2005 that pushed coverage from almost zero to 23.6 percent within just a few years to analyze whether a higher supply of childcare eases the return to the labor force after pregnancy. Prior research only finds small and weak effects on average, just as we confirm for the German case. Estimating an average treatment effect is interesting for a first impression. However, in order to examine selection behavior, we estimate marginal treatment effects along the distribution of observables and unobservables. This procedure reveals transmission channels and uncovers substantial heterogeneity in marginal returns to public childcare reforms which are informative to contrast costs and benefits of the policy reforms.

First, we detect a significant increase of the average probability to work full time from childcare utilization by 13.2 pp. Foreign-born mothers from another country of the EU, however, also significantly increase their employment at the extensive margin. On the contrary, no employment effects are found for non-Union migrants, although this group also significantly increased the utilization of public childcare in response to the reforms. Second, we find empirical evidence that private childcare arrangements are at least partially crowded out and substituted by public childcare slots. Thus, mothers who shift from private childcare to a public caring slot, weakens potential employment effects and are one reason for the small magnitude of estimated ATEs. Third, effects are driven mainly along the intensive margin which explains why effects on the size of the female labor force are barely detectable. At the extensive margin, positive selection on gains are found, so that a small fraction of mothers with the lowest resistance to early public childcare shift from non-employment to part-time jobs. At the intensive margin, we find a reverse selection on gains whereas a substantial share of mothers (40 percent) with median desire to demand public childcare react with an increase in the probability to work full time of at least 50 percentage points because of eligibility for a public childcare slot. However, mothers with the largest resistance toward early public childcare do not gain. Thus, if the supply of public childcare is expanded from a modest to a more generous level of coverage of about one third, those with average resistance gain the most.

This paper concludes that effects from family policy instruments are very heterogeneous regarding household composition, relationship status, and ethnic origin. Small employment effects are attributable on average to certain groups that have substantial gains while a majority of the population does not gain. Thus, the small ATE is not small because employment effects are homogeneously small across the entire population. For the design of policy instruments, this finding outlines the importance of questioning whether those with the most special needs—for example, lone parents—would benefit. We conclude that programs better customized for those with particular needs potentially increase the benefit of family policy instruments. Thus, the application of MTE helps to draw a more complete and informative cost-benefit analysis. The positive link between childcare utilization and maternal employment also contributes to the literature that considers children’s skills. Felfe and Lalive (2018) suggests that maternal employment is one transmission channel between childcare and children’s skills because higher household income due to increased maternal labor supply may also affect children’s skills.

Notes

This approach can be formulated in a reduced form. Otherwise, if information on actual public childcare utilization is available, it can be transferred to the two-stage IV procedure.

Note that each estimate presented in Column 5 of Table 1 refers to the effect from eligibility. For ITT estimates in Panel A, this means that labor supply effects from an increase in childcare coverage from zero to full coverage are displayed.

Although it is senseful to account for general messages from those three papers, we refrain from comparing the estimated effect size from quasi-experimental studies and simulated effects in the following.

A pure consideration on this indicator may be misleading. In Italy, the employment gap amounts to only 2.8 pp, which can be explained by a general low labor market attachment of women of below 60 percent. Also, the current economic situation of countries needs to be considered.

For ease of presentation, we drop the index i and the time index t in this section.

Based on \(Y=(X^{\prime} {\beta }_{0}+{U}_{0})+X^{\prime} ({\beta }_{1}-{\beta }_{0})D+({U}_{1}-{U}_{0})D\) and assuming E(U1∣X) = E(U0∣X) = 0 we obtain Eq. (9). Equation (11) demonstrates that heterogeneity in treatment effects can be the result of both observed (\({X}_{it}^{\prime}({\beta }_{1}-{\beta }_{0})\)) and unobserved heterogeneity characteristics captured by ∂K(p)/∂p. The model allows both parts to be correlated. Because we rely on parametric estimations, we do not impose the need on our model to separate the exact source of heterogeneity.

Further estimations not presented in this paper attempt semiparametric instead of parametric estimation. Moreover, estimating the first stage by logit and linear probability leaves the main findings also unchanged. In addition, Cornelissen et al. (2018) and Yamaguchi et al. (2018) suggest to estimate nonlinear relationship between childcare coverage and child utilization. However, adding squared and cubic terms of childcare coverage does not improve the results.

The transition year 2005 is excluded from the empirical analysis.

Note that questions on the utilization of public childcare are surveyed in each year since 1984. However, questions regarding demanding private childcare are not surveyed in 1998 and 2003.

If we allow δ2 to vary by survey year, we specify Eq. (2) in the following way: \({D}_{it}={\delta }_{0}+{\delta }_{1}Coverag{e}_{kt}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{l = 2006}^{2015}{\delta }_{l}Coverag{e}_{kt}Yea{r}_{t}^{l}+C_{kt}^{\prime} {\delta }_{3}+X_{it}^{\prime} \pi +{\lambda }_{t}+{u}_{it}\). In this case, δl varies between 0.0165 and 0.0308, while the second stage stays robust in magnitude.

Due to some time lag between application for a childcare slot and utilization of this slot, some studies suggest to use lagged childcare coverage instead of current childcare supply. However, the results stay rather robust if lagged childcare utilization is instrumented by lagged childcare coverage. Moreover, the MTE curves presented in Section 5 do not change noteworthy.

Moreover, the introduction of home care allowance that pays mothers a compensation payment if they look after their children under the age of three at home has to be considered (for details, see Fendel and Jochimsen 2017). However, if such compensation payments would have any effect, it would weaken incentives to work, so that our estimates can be seen as lower bounds.

Note that a share of 20.6 percent of lone parents is employed. Thus, estimations conditional on employment for this sample of 50 observations are omitted from Table 5.

Covariates on partners given in Table 2 are added in estimations only if married mothers are exclusively considered. 10.5 years of schooling displays the median of schooling years in our sample. In Germany, graduation from middle school (Realschule) corresponds to level two (lower secondary education) of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). This definition explains the description middle and high education. Note that using public childcare also significantly increases the probability of working full time when we only consider mothers with at least 11.5 schooling years which corresponds to the median.

Results behind this finding are available upon request. Note that choices are not exclusive. Parents may demand a part-time public child slot and also utilize some form of private caring service. However, if the share of 6.3 percent of mothers that use multiple forms of childcare is excluded from the analysis, the decrease in the probability of private childcare (36.0 pp) still exceeds the increase in the probability of public childcare utilization (−30.7 pp). The same holds true conditional on demanding any care.

A second approach to examine whether internal migration patterns shape results is provided by Havnes and Mogstad (2011), who recommend holding the first observed residency constant. This second approach does not change the shape of MTE curves.

References

Apps, P., & Rees, R. (2004). Fertility, taxation and family policy. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106, 745–763.

Baker, M., Gruber, J., & Milligan, K. (2008). Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 709–745.

Bassok, D., Fitzpatrick, M., & Loeb, S. (2014). Does state preschool crowd-out private provision? The impact of universal preschool on the childcare sector in Oklahoma and Georgia. Journal of Urban Economics, 83, 18–33.

Bauernschuster, S., Hener, T., & Rainer, H. (2016). Children of A (Policy) revolution: the introduction of universal child care and its effect on fertility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14, 975–1005.

Bauernschuster, S., & Schlotter, M. (2015). Public child care and mothers’ labor supply - evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 1–16.

Bettendorf, L. J. H., Jongen, E. L. W., & Muller, P. (2015). Childcare subsidies and labour supply - evidence from a large Dutch reform. Labour Economics, 36, 112–123.

Bick, A. (2016). The quantitative role of child care for female labor force participation and fertility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14, 639–668.

Bien, W., Rauschenbach, T. & Riedel, B.Wer betreut Deutschlands Kinder? DJI-Kinderbetreuungsstudie. Berlin: Deutsches Jugendinstitut.

Björklund, A., & Moffitt, R. (1987). The estimation of wage gains and welfare gains in self-selection models. Review of Economics and Statistics, 69, 42–49.

Blau, D.M. (2000). Child care subsidy programs. NBER Working Paper No. 7806.

BMFSFJ (2017). Kindertagesbetreuung Kompakt. Ausbaustand und Bedarf 2016. Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ), Berlin, 02.

Brave, S., & Walstrum, T. (2014). Estimating marginal treatment effects using parametric and semiparametric methods. The Stata Journal, 14, 191–217.

Brilli, Y., Del Boca, D., & Pronzato, C. D. (2016). Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and childrenas development? Evidence from Italy. Review of Economics of the Household, 14, 27–51.

Burger, K. (2010). How does early childhood care and education affect cognitive development? An international review of the effects of early interventions for children from different social backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 140–165.

Busse, A. & Gathmann, C. (2018). Free daycare and its effects on children and their families. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11269.

Carneiro, P., Heckman, J. J., & Vytlacil, E. J. (2011). Estimating marginal returns to education. American Economic Review, 101, 2754–2781.

Carta, F., & Rizzica, L. (2018). Early kindergarten, maternal labor supply and children’s outcomes: evidence from Italy. Journal of Public Economics, 158, 79–102.

Cascio, E. U. (2009). Maternal labor supply and the introduction of kindergartens into American public schools. The Journal of Human Resources, 44, 140–170.

Cascio, E. U., Haider, S. J., & Nielsen, H. S. (2015). The effectiveness of policies that promote labor force participation of women with children: a collection of national studies. Labour Economics, 36, 64–71.

Cornelissen, T., Dustmann, C., Raute, A., & Schönberg, U. (2018). Who benefits from universal child care? Estimating marginal returns to early child care attendance. Journal of Political Economy, 126, 2356–2409.

Ermisch, J. F. (1989). Purchased child care, optimal family size and mother’s employment. Journal of Population Economics, 2, 79–102.

Felfe, C. & Lalive, R. (2012). Early child care and child development: for whom it works and why. IZA Discussion Paper No. 7100.

Felfe, C., & Lalive, R. (2018). Does early child care affect children’s development? Journal of Public Economics, 159, 33–53.

Felfe, C., Lechner, M., & Thiemann, P. (2016). After-school care and parents’ labor supply. Labour Economics, 42, 64–75.

Fendel, T. & Jochimsen, B. (2017). Child care reforms and labor participation of migrant and native mothers. IAB Discussion Paper No. 9/2017.

Fitzpatrick, M. D. (2010). Preschoolers enrolled and mothers at work? The effects of universal prekindergarten. Journal of Labor Economics, 28, 51–85.

Fitzpatrick, M. D. (2012). Revising our thinking about the relationship between maternal labor supply and preschool. Journal of Human Resources, 47, 583–612.

German Federal Parliament. (2008). Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung: Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Förderung von Kindern unter drei Jahren in Tageseinrichtungen und in der Kindertagespflege (Kinderförderungsgesetz - KiföG). Drucksache 16/10173, 28th August in 2008.

Geyer, J., Haan, P., & Wrohlich, K. (2015). The effects of family policy on maternal labor supply: combining evidence from a structural model and a quasi-experimental approach. Labour Economics, 36, 84–98.

Givord, P., & Marbot, C. (2015). Does the cost of child care affect female labor market participation? An evaluation of a French reform of childcare subsidies. Labour Economics, 36, 99–111.

Goux, D., & Mourin, E. (2010). Public school availability for two-year olds and mothers’ labour supply. Labour Economics, 17, 951–962.

Haan, P., & Wrohlich, K. (2011). Can child care policy encourage employment and fertility? Evidence from a structural model. Labour Economics, 18, 498–512.

Hank, K., Kreyenfeld, M., & Spieß, C. K. (2004). Child care and fertility in Germany. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 33, 228–244.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011). Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 1455–1465.

Heckman, J. J., Urzua, S., & Vytlacil, E. (2006). Understanding instrumental variables in models with essential heterogeneity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88, 389–432.

Heckman, J. J., & Vytlacil, E. (1999). Local instrumental variables and latent variable models for identifying and bounding treatment effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 96, 4730–4734.

Heckman, J. J., & Vytlacil, E. (2005). Structural equations, treatment effects, and econometric policy evaluation. Econometrica, 73, 669–738.

Huesken, K. (2010). Kita vor Ort: Betreuungsatlas auf Ebene der Jugendamtsbezirke 2010. Technical Report. Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V.

Kline, P., & Walters, C. R. (2016). Evaluating public programs with close substitutes: the case of head start. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131, 1795–1848.

Lalive, R., Schlosser, A., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2014). Parental leave and mothers’ careers: the relative importance of job protection and cash benefits. Review of Economic Studies, 81, 219–265.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1363–1402.

Lundin, D., Mörk, E., & Öckert, B. (2008). How far can reduced childcare prices push female labour supply?. Labour Economics, 15, 647–659.

Nollenberger, N., & Rodriguez-Planas, N. (2015). Full-time universal childcare in a context of low maternal employment: quasi-experimental evidence from Spain. Labour Economics, 36, 124–136.

Raute, A. (2019). Can financial incentives reduce the baby gap? Evidence from a reform in maternity leave benefits. Journal of Public Economics, 169, 203–222.