Abstract

In the midst of a global pandemic, higher education saw a modality shift to online learning that caused panic and discomfort as many instructors lacked the skills, resources, and didactic aptitude in this response (Lederman, The shift to remote learning: The human element. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/25/how-shift-remote-learning-might-affect-students-instructors-and, 2020). The current review discusses the impact of this article for successful learning design as well as applications, limitations, constraints and future suggestions during the COVID-19 era. Specifically, this paper is in response to the article entitled, “The process of designing for learning: understanding university teachers’ design work” (Bennett et al., The process of designing for learning: Understanding university teachers’ design work. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65, 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9469-y, 2017). The impact of the article under review can provide a roadmap to expert instruction with its focus on flexibility across interdisciplinary higher education fields of knowledge. In application, the findings of Bennett and her colleagues work, suggested designing for efficiency, broad considerations to specific details, and design and refining processes. The limitations of the current study under review, included having participants remember particular experiences of design with one-off interviews and no significant follow up. Given the aforementioned limitation, the next stage of research could be to develop a more explanatory and then prescriptive study to explore the rationale behind design decisions and strengthen implications. The descriptive framework of the current study allows educators and students opportunities to co-design authentic meaning making experiences given cultural relevant pedagogy. Ultimately, the current review concludes from a learning design perspective that focuses on culturally relevant educational ecosystems and interactive media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Valuable impact

Higher education is witnessing an increasing shift to online learning that has caused panic and discomfort as many instructors lacked the skills, resources, and didactic aptitude in this response (Lederman 2020). Our current shift to digital is explored through a study entitled, “The process of designing for learning: understanding university teachers’ design work,” as it provides an overarching framework for the development of learning design among higher education professors (Bennett et al. 2017). Considering the expansion of online needs in the education industry, learning design must be interactive and interdependent (Engerman and Otto 2018). Bennett and her colleagues, explored the design processes of 30 experienced higher education instructors. All educators in the study used approaches to design that considered student needs and prior knowledge (Bennett et al. 2017). While recognizing the aforementioned approach, pivoting to learning design has never been more critical, as we consider the heightened need for higher education intuitions to increase diversity, student satisfaction rates as well as the pressures to enhance recruitment, graduation rates, and expectations of overall graduate quality (Goodyear 2015). Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) can help to fill these gaps and can be an important element to the current research. CRP seeks to improve teacher education through the appreciation of the asset’s students can bring to their work in classrooms (Ladson-Billings 2014, Ladson-Billings 1995; Hatley et al. 2017).

The current study under review impacts scholarship by strengthening the notion that learning design needs to be flexible, and technologies can be created to support representation, adaption, sharing and implementation through broad ranging colocation practices. It opens the door to engage in culturally relevant teaching methods that empower learners and has the potential to push students to have critical perspectives on policies and practices that have a direct impact on their lives and communities (Ladson-Billings 2014). Lastly, the impact of this paper can provide a roadmap to expert instruction as a process of design that provides opportunities for growth and less prescriptive content focus. Further discussion will explore the applications, limitations, constraints and future suggestions considering a culturally relevant lens for digital environments.

Application

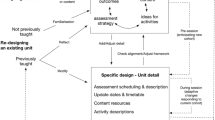

Approaches that focus on learner centers lead to more meaningful co-design processes that implement student needs along the way (Engerman and Otto 2018; Engerman 2016; Engerman et al. 2019a). Bennett, Agostinho, and Lockyer found that regardless of the starting point in design these expert teachers iteratively considered, “learning outcomes, the scope of the content to be covered, their general ideas for learning activities, and their assessment strategy” (2017, p. 139). The findings suggested three critical features of learning design including designing for efficiency, broad considerations to specific details, and design and refining processes towards student success. These design features leave room to integrate student cultural competencies as assets to empower them and improve understanding. Co-designed approaches that emphasize connections to the content, digital asset building and reflective practices respect the sociocultural aptitude of students and empowers them to take true ownership of their learning processes (Scott et al. 2010; Hatley et al. 2017).

Designing for efficiency

For the instructors within the study, the starting point of the design work was determined by the nature of the nuanced design problems. As the instructors began to design their lessons, they redesigned class experiences for efficiency. Reasons for redesigning included addressing feedback from students and colleagues, updating the content covered, making changes to perceived problems for learners, and changing how content is delivered to include online components among others (Bennett et al. 2017). Efficiency was defined in terms of effectiveness and accommodation to student learning needs. Here we may see another opportunity for enhanced learning design as student’s diverse and cultural backgrounds can be assets in developing digital learning tools and instruction of content (Scott et al. 2013). CRP encourages the instructors to develop experiences that connect with students in social and cultural terms as well as provide opportunities for reflection. In their study on designing digital games, Scott et al. (2013) saw learners notice gaps in their own understanding, propose and implementing solutions as a result of their established connections, asset build and reflect on their processes. Efficiency as a CRP concept also ends with student growth into meaningful ownership of their learning processes.

Broad to specific detailed design

The instructor participants in this study described a macro to micro design as they needed to understand the unit’s overarching framework before filling in finer details. Broad frameworks create more opportunities for a co-designed process with students that can provide meaningful engagement through participation (Engerman et al. 2019b). Veteran educators understand that the broad structure of a lesson or unit allows room for students to respond and give feedback performance and knowledge gaps that need to be filled by the details of activities and content delivery methods. Considering the current digital age, students respond to the ability to participate in the digital communities they inhabit (Engerman and Otto 2018).

Iterative design processes

Seasoned instructors are able to be flexible in their approaches and delivery, which could mean a change in technology, content, or delivery methods. The study demonstrated the importance of designing before, during and after a unit’s implementation. Much like the professional instructional design process, these design processes were nonlinear as recursive design required interrelated components (Dick et al. 2015). Despite the multi-disciplinary faculty, we see cohesion around iterative design being well known within the instructional design profession. Iterative processes of design, refine, redesign is necessary to align student needs and improve performance outcomes (Dick et al. 2015). In order to meet students’ needs we must recognize that students often engage with content in class that align with their social orientations and cultural capital (Sanford and Madill 2006; Blair and Sanford 2004; Engerman 2016).

Limitations and constraints

The article, “The process of designing for learning,” was based on a single unit of analysis of teacher design within a descriptive frame through a streamlined qualitative data analysis. However, we believe the limitations and constraints were primarily in the one-off interviews of participants to recall professional practices opposed to observations and student perspectives of impact. The expert instructors within the study designed instructional experiences that were admittedly informed by learner centered approaches. If so, then more data would be useful that focuses on teacher practices and student responses. These are critical factors to better triangulate what teachers are doing, which would require observational data and learner inquiry. In addition, data on student inquiry could describe how the content design is being molded into specifics as learners fill the gaps and dictate the scaffolding that teachers perform. Students need to experience social and cultural value in their activities based on engagement, ownership and satisfactory outcomes. This is the reason we consider CRP within teacher design by building connections to social and cultural capital, allowing for assets to be built, and reflective opportunities through co-designed processes.

Future suggestions

We have provided a review towards the shift to digital based on research gathered from educators with cross curricular and extensive online teaching experiences in “The process of designing for learning: understanding university teachers’ design work,” provides an overarching framework for the development of learning design (Bennett et al. 2017). The researcher’s work shows the potential for higher education instructors to develop meaning experiences towards the shift to digital. The study under review was exploratory, descriptive in nature and fills a gap in the literature focused on the online higher education process which provides opportunities for further study. Towards a more prescriptive study of implementation, the next stage might be to develop a more explanatory investigation that unpacks the teacher behaviors from observation by embedding observation that leads to more follow up inquiry. Including a historical view, experiential view and then a reflective view (Seidman 2019) could provide a more detailed account of not only the descriptions but also could have provided a deeper level of description with stronger participant triangulation (Rossman and Rallis 2011). In addition, a future study could include student perspectives to understand how their understanding informs a codesigned process narrated through a thematic analysis (Braun and Clark 2006). These two avenues may provide a more holistic approach to the learning environment and describe why teachers make specific curriculum design decisions as they navigate through their online course design processes.

References

Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2017). The process of designing for learning: Understanding university teachers’ design work. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65, 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9469-y.

Blair, H. A., & Sanford, K. (2004). Morphing literacy: Boys reshaping their school-based literacy practices. Language Arts, 81(6), 452–461.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. ISSN 1478-0887.

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. O. (2015). The systematic design of instruction (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Engerman. (2016). Call of duty for adolescent boys: An ethnographic phenomenology of the experience of a gaming culture. Doctoral Dissertation. Retrieved from https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/t722h880z.

Engerman, J. A., MacAllan, M., & Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2019a). Understanding learning in video games: A phenomenological approach to unpacking boy cultures in virtual worlds. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09930-2.

Engerman, J. A., & Otto, R. (2018). Journey of the Esports Digital Warrior. Poster presentation at Connected Learning Summit. Irvine, CA: Carnegie Mellon ETC Press.

Engerman, J. A., Raish, V., & Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2019b). Applying systems thinking to learner centered user-design for game and cyber school learning contexts. In M. Spector, B. Lockee, & M. Childress (Eds.), Learning, design, and technology. An international compendium of theory, research, practice, and policy volume 16 titled: Systems thinking and change. New York, NY: Springer.

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching as design. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2, 27–50.

Hatley, L., Winston-Proctor, C. E., Paige, G. M., & Clark, K. (2017). Culture and computational thinking: A pilot study of operationalizing culturally responsive teaching (CRT) in computer science education. In A. Benson, R. Joseph, & J. Moore (Eds.), In culture, learning, and technology (pp. 109–126). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: Aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84.

Lederman, D. (2020). The shift to remote learning: The human element. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/03/25/how-shift-remote-learning-might-affect-students-instructors-and.

Rossman, G. B., & Rallis, S. F. (2011). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sanford, K., & Madill, L. (2006). Resistance through video game play: It’s a boy thing. Canadian Journal of Education. Revue Candienne del’ education, 287–306.

Scott, K. A., Clark, K., Sheridan, K., Hayes, E., & Mruczek, C. (2010, March). Engaging more students from underrepresented groups in technology: What happens if we Don’t? In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 4097–4104). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Scott, K. A., Sheridan, K. M., & Clark, K. (2013). Culturally responsive computing: A theory revisited. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(4), 412–436.

Seidman, I. (2019). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. New York: Teachers College Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Engerman, J.A., Otto, R.F. The shift to digital: designing for learning from a culturally relevant interactive media perspective. Education Tech Research Dev 69, 301–305 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09889-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09889-9