Abstract

I modify the skewed lottery task introduced by Grossman and Eckel (Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51(3), 2015) to eliminate the effects of loss aversion as a potentially confounding explanation for the strong preference for skewed lotteries and increase in risk taking that they observe when skew increases. I also test for framing effects by reversing the order of the task. Like previous studies, a majority of subjects prefer skewed lotteries relative to those with no skew, but this preference is dampened when loss aversion is eliminated as a confound and the order of the task is reverse. More importantly, introducing skew is unlikely to cause an increase in risk taking in this task.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

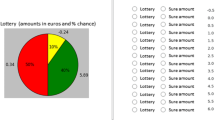

Outcomes are rounded to the nearest nickel to reduce cognitive effort and to reduce subject suspicions that a trick may be hiding in more complex numbers.

GE2015 did not allow subjects to select a different lottery in the same row as the current selection. That is, subjects could not alter the riskiness of their choices without increasing skew. Subject’s choices were not restricted in this way in this experiment. Any presented lottery was available for selection in each round.

The median subject in this experiment chose Option D, which implies a CRRA coefficient between 0.37 and 0.53, and the average number of safe choices made in the HL MPL is typically 5 or 6, which corresponds to CRRA bounds between 0.15 and 0.68.

A total of 160 subjects completed the entire experiment, but the Round 3 choices for the first eight subjects were lost due to a coding error. Subjects earned an average of $32.94 for the entire experiment, which took about an hour to complete.

Round-by-round distribution of lottery choices by risk and skew are shown in Table 8 in the Appendix.

An ordered probit model in which the dependent variable is the skew of the Round 3 selection of the subject also indicates that there is a significant order effect.

Both percentages are more than 10 percentage points less than GE2015 and are statistically significantly different from the corresponding percentages in GE2015 (p-value= 0.058 from test that first proportion equals 0.376 and p-value= 0.066 from test that second proportion equals 0.427).

The mean of Difrisk equals the difference between mean riskiness in Round 3 and Round 1 shown in Table 5 for each treatment.

Only two subjects spent more than ten minutes on this task, including instructions, and the average was less than five minutes.

References

Andersen, S., Harrison, G.W. , Lau, M.I. , & Rutström, E.E. (2006). Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Experimental Economics, 9, 383–405.

Bar-Hillel, M. (2015). Position effects in choice from simultaneous displays: A conundrum solved. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(4), 419–433.

Barberis, N. (2013). Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1), 173–196.

Bruine de Bruin, W. (2005). Save the last dance for me: Unwanted serial position effects in jury evaluations. Acta Psychologica, 118, 245–260.

Bruine de Bruin, W., & Keren, G. (2003). Order effects in sequentially judged options due to the direction of comparison. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 92(1-2), 91–101.

Brünner, T., Levínský, R., & Qiu, J. (2011). Preferences for Skewness: Evidence from a binary choice experiment. The European Journal of Finance, 17(7), 525–538.

Butler, D., & Loomes, G. (2011). Imprecision as an account of violations of independence and betweenness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 80(3), 511–522.

Butler, D.J. , & Loomes, G.C. (2007). Imprecision as an account of the preference reversal phenomenon. American Economic Review, 97(1), 277–297.

Christenfeld, N. (1995). Choices from identical options. Psychological Science, 6(1), 50–55.

Cubitt, R.P. , Navarro-Martinez, D., & Starmer, C. (2015). On preference imprecision. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 50, 1–34.

Dayan, E., & Bar-Hillel, M. (2011). Nudge to nobesity II: Menu positions influence food orders. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(4), 333–342.

Drichoutis, A.C., & Lusk, J.L. (2016). What can multiple price lists really tell us about risk preferences? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 53, 89–106.

Ert, E., & Fleischer, A. (2016). Mere position effect in booking hotels online. Journal of Travel Research, 55(3), 311–321.

Grossman, P.J. , & Eckel, C.C. (2015). Loving the long shot: Risk taking with skewed lotteries. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 51(3), 195–217.

Habib, S., Friedman, D., Crockett, S., & James, D. (2017). Payoff and presentation modulation of elicited risk preferences in MPLs. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 3(2), 183–194.

Harrison, G.W. (2006). Hypothetical bias over uncertain outcomes. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Holt, C.A., & Laury, S.K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–55.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L., & Thaler, R.H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206.

Lévy-Garboua, L., Maafi, H., Masclet, D., & Terracol, A. (2012). Risk aversion and framing effects. Experimental Economics, 15(1), 128–144.

Miller, J.M., & Krosnick, J.A. (1998). The impact of candidate name order on election outcomes. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 62(3), 291–330.

Nisbett, R.E., & Wilson, T.D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231–259.

Rabin, M., & Thaler, R.H. (2001). Anomalies: Risk aversion. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(1), 219–232.

Santos-Pinto, L., Astebro, T., & Mata, J. (2009). Preference for skew in lotteries. Evidence from the laboratory. Working paper.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Unkelbach, C., Ostheimer, V., Fasold, F., & Memmert, D. (2012). A calibration explanation of serial position effects in evaluative judgments. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 119 (1), 103–113.

Valenzuela, A., & Raghubir, P. (2009). Position-based beliefs: The center-stage effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19, 185–196.

Acknowledgements

This research is partially funded by a University of Montana Small Grant. I am especially grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from Doug Dalenberg. I also thank Lynzee Lee, Mason Gedlaman, and Aaron Nicholson for assistance with the administration of the experiment. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: A

Appendix: A

1.1 A.1 Oral instructions

(Read aloud before experiment starts to subjects)

Thank you for participating in this experiment. Your participation will allow us to explore questions that economists have about individual decision making, preferences, and cognitive ability.

This experiment will have multiple sections. In some sections, you will have the opportunity to make choices and answer questions that may affect your payment. Please read the instructions carefully to ensure that you understand whether, and how, your choices in a particular section will affect your payment.

Additionally, some of the sections will ask you to make choices that reveal your attitudes or preferences. There are no correct answers for these choices. Other sections will ask you questions that do have a correct answer. Please do your best to answer these questions correctly.

After you have completed the experiment, you will reach a page that displays your total payoff for participation in the experiment today. This page asks you to stop and raise your hand so that we can verify your payoff, please quietly raise your hand when you reach this page and we will verify payment.

You will be paid in cash today before you leave. Everyone here will start the experiment with a $6 show-up payment. During Section 2 of the experiment, you will have the opportunity to “wager” some or all of that $6 in order to have a chance at getting a much larger payoff. Someone who chooses this option could lose some or all of his or her show-up payment. However, you are not required to choose an option that puts your show-up payment at risk. Moreover, other sections of the experiment will allow you to have the chance to receive money. As a result, everyone here will be paid at least $0.30 at the end of the experiment, no matter what happens.

If you decide to leave early, you may do so. If you do leave early, you will be allowed to keep the $6 show-up payment, but you will forfeit any experimental earnings.

We understand that you may have questions, but it is important that we maintain the integrity of the experiment by minimizing talking and other disruptions. If you have any questions before or during the experiment, please write it down on the card next to your computer, raise your hand, and wait until one of us comes over to your computer terminal. If it is a question that can be answered without compromising the integrity of the experiment, then we will do so.

Finally, we ask that you do not discuss this experiment with anyone who may also participate in this experiment. Thank you.

1.2 A.2 Lottery choice distribution by round

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, M.P. Liking the long-shot … but just as a friend. J Risk Uncertain 61, 245–261 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-020-09342-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-020-09342-5