You also ask what is going on inside me. That is difficult to define. As you know, ever since 1950 a big change has been in progress inside me—a reorientation in the entire attitude to life. This, of course, creates certain problems and a certain restlessness, and on many things one doesn’t know what to think and what to say. Perhaps that is the reason why you don’t ‘feel me in my letters.’

Schumacher to his wife Anna Maria, March 3, 1954

INTRODUCTION

On January 13, 1955, after a long flight from New York, Ernst Friedrich (“Fritz”) Schumacher arrived at the Kanbawza Palace hotel in Rangoon. With five years behind him at the UK National Coal Board, he had taken three months’ leave and was now in Burma on secondment to the United Nations (UN). On the face of it, it was just another mission by a Western economist, his task being to evaluate the Union of Burma’s new plan for economic and social development. For Schumacher, however, the Burmese trip was also charged with personal significance, and it would prove to be pivotal for his subsequent life and career.

Until the end of the 1940s, the German émigré had been a fairly conventional economist: a believer in Western growth and progress; for a number of years socialist in his politics; very knowledgeable in international trade and finance; and, under the influence of Nietzsche, stridently irreligious. Then, in or around 1950, he began to undergo a seismic shift in personal philosophy, which saw him question and revise many of his beliefs. In the course of several years of self-examination and spiritual quest, he began to take a critical view of modernity and to question the worth of a civilization based on technological development and economic growth.

That period of self-scrutiny heightened the allure of the East for Schumacher. And so, after four or five years’ preparation, in 1955, he headed for Burma, ostensibly to work as a UN economic consultant but equally to learn more about life in an Eastern society and about Buddhism in practice. While the three months spent there did not make a Buddhist of him, it did mark him in many ways. For one, he was greatly affected by the beauty of a traditional society and by the quality of life of its Buddhist citizens. For another, it obliged him to reconcile, so to speak, his economic thinking with his new philosophical outlook. This he did, not so much in his professional consultancy work as in “Economics in a Buddhist Country,” his passionate, private response to the threat posed by Western development to Burmese culture.

Burma marked the birth of Schumacher the critical economist, and his work would never be quite the same again. When he returned to England, it was in the conviction that modern development was far from being the panacea that many people held it to be, and that, more generally, one’s approach to economics was necessarily reflective of deeper existential commitments concerning human purpose or “man’s place on earth.” From then on, his writings on economic development, in both the East and the West, emphasized the need for limitation, restraint, and non-violence, inspired by Buddhism, Gandhi, and other influences gathered along the way.

Drawing on his letters, papers, and personal library, we tell the story of Schumacher’s mid-life engagement with Buddhism and his life-changing voyage to Burma. We first consider his conventional years and then his period of “awakening” in the early 1950s. We then follow him to Rangoon in 1955, where his encounter with encroaching Western development galvanized him to write about economics in relation to Buddhism. Finally, we discuss the influence of Burma and Buddhism upon his subsequent work and his achievement of public renown.

II. CONVENTION AND CRISIS

Until the end of the 1940s, Fritz Schumacher appeared bound for a conventional career. The second son of Hermann Schumacher, professor of economics at Bonn University, he began studying law and economics at the same institution but, within a few months, was off to England. There, he attended classes at the London School of Economics and spent time at Cambridge, where he encountered John Maynard Keynes, Arthur Cecil Pigou, and Dennis Robertson. Upon returning to Germany, he won a Rhodes Scholarship, and quickly left, in October 1930, for New College, Oxford. He began a two-year B.Litt. degree in economics and politics, and while he didn’t particularly enjoy Oxford, he did make friends with David Astor, later editor of The Observer and an important future ally.Footnote 1

In September 1932, extending his studies by a year, Schumacher left for Columbia University, New York, where he began conducting research on banking and gold with Professor Parker Willis, the Wall Street critic. In 1933, he accepted a year-long post as lecturer at Columbia’s School of Banking. In April 1934, he returned to Germany, where he refused to acquiesce with the Nazi regime, and, suffering ill health and depression, did not complete the work for his Oxford B.Litt.

In 1935, he married Anna Maria “Muschi” Petersen, daughter of a prominent Hamburg family, having already begun working for their import-export business in Berlin. The following year, he moved to London, to a financial post with Unilever in the city, with Muschi joining him in 1937. When war broke out in September 1939, they were separated from their German families for its duration. For Muschi, this was the beginning of a life of separation from Germany that would weigh heavily upon her for many years.

Schumacher initially spent several wartime months as an enemy alien at Prees Heath internment camp in the Shropshire countryside. It was here that he met fellow expatriate Kurt Naumann, a communist who converted him, an erstwhile liberal, to socialism. From mid-1940, Schumacher was allowed to avoid detention and work instead as a farm laborer at Eydon Hall, Northamptonshire. This was the estate of Robert Brand, who, married to David Astor’s aunt, was a Lazard Brothers banker, an acquaintance of Keynes, and a higher civil servant during the war. Living in an estate cottage with his wife and now two sons, Schumacher passed a year and a half on the farm, by day laboring in the fields, by night writing papers on economic affairs and voluminous letters to friends. Those letters reveal much about the evolution of the mandarin’s son: his new-found interest in farming,Footnote 2 his strident rejection of religion,Footnote 3 and his recent conversion to socialism.Footnote 4 The draft papers he wrote concerned the situation in Germany, what would happen when the Nazis had been defeated, and how Europe and the international order should be governed thereafter.Footnote 5

Probably through Brand, Schumacher’s writing on multilateral clearing drew the attention of Keynes, resulting in an invitation to London for discussions.Footnote 6 He then moved in 1942 to the wartime Oxford Institute of Statistics, alongside Michael Kaleçki, Fritz Burchardt, and Thomas Balogh. With Nicholas Kaldor and Joan Robinson, he contributed to William Beveridge’s (1944) Full Employment in a Free Society—without receiving explicit credit, according to his daughter—and he began to write Fabian articles for newspapers, including The Observer and The Times.

Throughout the 1940s, Schumacher was cocksure in his attachment to socialism and his rejection of religion. “[It] is a large and, I am afraid, an almost hopeless task to overcome the deeply ingrained habits of thought of those whose thinking is steeped in metaphysics and theology,” he wrote in a typically strident letter to a patient Christian friend.Footnote 7 Later that year, he wrote to his brother-in-law, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg, feistily refuting criticism:

Your reaction to my arguments will be that you have heard all this radical stuff before, and my reaction to yours is that, having been reared on apologetic economics, on apologetic sociology and history, and on reactionary religion and philosophy, they merely make me feel happy that I have at last overcome the deficiencies of my original environment.Footnote 8

After the war, however, some of that self-assurance began to break down. Returning to Germany in 1945 to work with John K. Galbraith’s Strategic Bombing Survey, he was deeply affected, seeing the effects of the war and confronting his family’s wartime history. His younger brother had been killed in December 1941, fighting for Germany on the Russian front, and their ageing father, Hermann, continued to sing his praises. His brother-in-law, Heisenberg, was at the center of the German atomic controversy, and, in the eyes of external observers, suspiciously close to the German establishment. His sister, Edith, was the wife of Nazi critic and socialist author Erich Kuby, who was vociferous in his opposition to the Hitler regime. For Schumacher, it was a challenging, unsettling time.

The following year, now a British subject, he returned again to Germany, as economic advisor on postwar reconstruction with the British Control Commission. Walking the streets of Berlin for the first time in a decade, he was dumbstruck by what had become of German civilization: “You cannot believe it. No person can imagine such a thing. It is impossible to believe it even when you see it. I couldn’t sleep afterwards and had a headache all the next day. Dante couldn’t describe what you see there. A desert.”Footnote 9 Thus, while professionally he continued to promote a broadly leftist agenda, advocating the nationalization of German heavy industry, privately there appeared a new humility. Among the ruins of German society, he began to pose larger existential questions, turning to Epictetus, August Bier, and Ortega y Gasset. In the spring of 1948, during a lengthy confinement with pneumonia, he read Arthur Schopenhauer. Faced with the German ethical legacy, he even began to talk about the need for Christian charity and forgiveness.

When he finally left Germany in 1949, he was glad to get out of it—away from the military bureaucracy, the infighting, the squabbling between the British and the Germans. That year, he turned down an offer of a post as economic advisor from the president of Burma, and another from the UN in Geneva—an indication that he was known in these international circles—and accepted an appointment at the National Coal Board back in England. By mid-1950, he and the family were settling at Holcombe, a large house on three and a half acres in Caterham, Surrey. From there, he began commuting daily to his office in Hobart House in London, ostensibly building a new career in the economics of coal and energy.

One might have expected that, at this point, Schumacher would have settled down, yet he did quite the opposite, intensifying the personal quest triggered by his German trauma. That shock had called into question the achievements of modern society, the role of science and technology therein, and the relevance of metaphysical commitment. It had also left him—a German in England who insisted on speaking English to his children and wrote in English to his German wife—wondering about matters of personal identity and belonging. Instead of settling, therefore, he entered a phase of existential self-examination.

There were several stimuli for this “reorientation in the entire attitude to life,” as he called it: intensely serious explorations that led him to question features of a modern society he had heretofore taken for granted. In a phrase, he turned to horticulture, esoterics, and Buddhism. More pithily, to “the garden, Gurdjieff and Gautama.”

While on the farm at Eydon, Schumacher had begun reading some of the interwar literature on rural revival and the transformation of agriculture through the use of mechanization and chemicals. Now at Holcombe, he plunged into his own garden and immersed himself further in such reading. The key contributors here included George Stapledon, Lord Northbourne, Albert Howard, Robert McCarrison, Guy T. Wrench, and Eve Balfour.Footnote 10 They wrote variously about the importance of the Law of Return—i.e., the idea that the produce of the earth should return to nourish it, as the leaves do in the forest; about the damage to the environment posed by the relinquishment of the horse in favor of the tractor, and by the replacement of natural methods by chemical fertilizers and pesticides; and about the dependence of human health, via the consumption of agricultural produce, on the quality of the soil. Some of the literature had a strong “Eastern” connection, describing, for example, the durability of traditional forms of agriculture in China; the “Indore” method of compost making developed in India; or the health benefits of wholesome, traditional diets—most famously, perhaps, that of the Hunza tribe in what was then northern India. With her 1943 manifesto, The Living Soil, Eve Balfour sparked the creation of the Soil Association, which was openly critical of the effects of modern “progress” in agriculture and sought to promote “organic” methods.Footnote 11 Not only did Schumacher cultivate his garden in this manner, but he joined the Soil Association and had them present a film at his Coal Board offices in the city. He assimilated the ideas of the Soil Association concerning cultivation, diet, and health, and was to remain involved with Balfour and her associates for the rest of his life.

It is perhaps a measure of the depth of his soul searching in the early 1950s that this slightly toughened Nietzschean sought solace in the esoteric teachings of George I. Gurdjieff and his follower Piotr Ouspensky. The Fourth Way, as it was known, was based on teachings that the Armenian mystic Gurdjieff had supposedly gathered during his travels among tribes in northeastern India and neighboring countries. It began with the premise that the individual, as an unthinking follower of routine, was typically not “awake” and did not truly know himself. Self-knowledge and awakening could be achieved only through a harsh regime of physical labor and spiritual training, led by a qualified adept. Schumacher became involved with the London Gurdjieffians around Ouspensky, with the most important for him being psychiatrist Maurice Nicoll (1884–1953) and scientist John G. Bennett (1897–1974). He was quite taken by Nicoll’s books, which interpreted the teachings of the Gospels in light of the “Work,” as the Gurdjieffian system was known.Footnote 12 After his own father’s death in 1952, Schumacher even went so far as to translate, with his mother, Nicoll’s (Reference Nicoll1950) The New Man into German. As for Bennett, he, like Schumacher, was involved in coal, running the British Coal Utilisation Research Board, and he also established a Gurdjieffian center at Coombe Springs, his home in Kingston-upon-Thames.Footnote 13 Schumacher attended lectures by Bennett and read his work, including his (1948) The Crisis in Human Affairs, which called the modern scientific era into question and emphasized the need for ethical awakening and the reassertion of traditional wisdom. Schumacher’s interest in the Gurdjieffian world lasted until at least the end of the decade and overlapped with his interest in Buddhism. As we shall see, when he went to Burma, the Gurdjieffian teachings would be an important point of reference for him as he encountered Buddhism in practice.

His interest in Buddhism owed much to the influence of another German exile in London, the inimitable Edward Conze (1904–1979), whom Schumacher appears to have met through the Buddhist Society. A former communist, Conze had fled the Nazis in 1933, and then eked out an existence in London as part-time teacher and activist with the National Council of Labour Colleges.Footnote 14 Although the author of several works in Marxism, including his (1938) An Introduction to Dialectical Materialism, by the end of the 1930s, provoked by witnessing the Civil War in Spain, Conze had undergone a serious personal crisis and abandoned Marx for Buddha. A gifted linguist, he quickly became an accomplished scholar and a translator of Buddhist texts.

Not only did Schumacher read Conze’s books, but he attended his lectures and became his friend. Under his influence, Schumacher began to acquire a significant library in Buddhism, which eventually reached some seventy volumes. He began to read the work of German scholars of Buddhism, of Eastern monks, and, significantly, of German expatriates-turned-Buddhist monks in Ceylon, the most well-known of whom were Nyanatiloka and Nyanaponika. In 1952, he wrote to his mother that his contact with Indian and Chinese philosophy and religion was so changing his way of thinking that he would later regard his forty-first year as a turning point in his life.

The soil, health, Eastern wisdom and modern decline, the promise of self-discovery, Buddhism … Schumacher’s personal quest of these years did not just heighten the allure of a journey to the East; it made it inevitable. To his wife, then on holiday in Egypt with her parents, he wrote: “Can you imagine what it means to me that you have actually been there, that is: in the East, outside Western civilization, have actually seen it with your own eyes,—when I am still being pressed to go to Burma. Another telegram arrived to-day, from Rangoon.”Footnote 15

III. BURMA, BUDDHISM, AND ECONOMICS

He was first formally approached by the UN in April 1954, with the job description expressly mentioning him and suggesting a one-year stay. The task was to advise the government on economic policies “to facilitate the balanced expansion of economic activity contemplated under the Government’s development plans.” Not a routine assignment, it would involve “advising Government at the highest level on subjects of far-reaching importance.”Footnote 16 Negotiating a three-month assignment and leave from his Coal Board post, he took the plane after Christmas.Footnote 17

On the way to Rangoon, he stopped in New York for a week of UN briefings. If he had loved that city as a student in 1933, he now saw it differently:

What I have seen of U.S.A. so far is quite mad and somehow—ungemütlich [uncomfortable]. One gets the impression that the primary pre-occupation of the American people is with motor cars: you see nothing but cars wherever you look, cars moving, cars shopping, cars parking, cars for sale, cars required and unrequired, all enormous and ugly. Also, roads, overhead and underneath, everywhere like a futuristic painting.Footnote 18

Arriving in Rangoon, he moved into the Kanbawza Palace, “a large and ugly building converted into a hotel” (see Figure 1). Although initially struck by the similarities between Burma and elsewhere, by late January he was emphasizing the particularities of the society and the threat posed by the West.

The people really are delightful. Everything I had heard about their charm and cheerfulness seems to be true. They move one in a very strange way. There is an innocence here which I had never seen before—the exact opposite of what disgusted me in New York. In their gay dresses and with their dignified and composed manners, they are lovable, and one really wants to help them if one but knew how. Even some of the Americans here say: ‘How can we help them when they are much happier and much nicer than we are ourselves?’

…

I think there really is some work for me here, but it may be negative rather than positive, persuading them not to do various things rather than telling them what to do. Because on the positive side they need no advice: as long as they don’t fall for this or that piece of nonsense from the West, they will be quite alright following their own better nature.Footnote 19

Figure 1. The Kanbawza Palace Hotel

Wikimedia Commons

Western Encroachment: Robert Nathan and the American Plan

The development plan to be assessed by Schumacher was the work of a group of American advisors. Following wartime damage to the economy and the achievement of the country’s independence in 1948, the Burmese government had retained the services of foreign consulting engineers and economists, including Pierce Management consultants; New York engineering firm Kappen, Tippetts, Abbet, McCarthy; and Washington, DC, economists Nathan Associates. A student of Simon Kuznets, Robert Nathan had become a successful development consultant in the Cold War period.Footnote 20 By 1953, these advisors had completed a massively detailed 1,000-page program for Burma, proposing, amongst other things, increased extraction of coal and other minerals; the construction of dams and irrigation projects for the development of agriculture; the extension and new construction of railways and highways; the development of electricity generation, using coal and hydroelectric power; and extensive industrial development, involving minerals, forestry, manufacturing, and small-scale industry.Footnote 21

Nathan prepared also a smaller, “Restricted,” 1954 report, “Pyidawtha. The New Burma,” for use by the government in promoting popular acceptance of the plan.Footnote 22 It insisted that the economic development of Burma could be achieved while preserving its culture and spiritual traditions; stressed the necessity of putting insurgency and brigandage to an end; and emphasized that the program went well beyond reconstruction, offering a new economic foundation and the promise of “dynamic growth for an indefinite future” (p. 8). Giving a little lesson on GDP, it promised that by 1960, the economy would be one-third bigger than it was at its pre-war peak, and said that Burma would need many more engineers, architects, economists, statisticians, and physical scientists, often with foreign training. In agriculture, it proposed intensification:

The most extensive improvement for most crops would come from the use of chemical fertilizers which, according to scientific tests in Burma, will increase yields by 30%. That is to say that by using fertilizer on the land he now works, a farmer will gain the same benefits he would receive from expanding his land by nearly one-third. (p. 37)

What was envisaged was a

thorough-going revolution in the structure of our agricultural economy, and in the methods of producing and marketing agricultural products. This revolution cannot come over-night. It will require many, many years. For it literally will involve radical changes in the daily practices, habits, and attitudes of the farmers and farm workers of Burma—two-thirds of our entire working population. (p. 46; emphasis in original)

Burma was to also build its own fertilizer factory, at Myingyan, manufacturing “ammonia, urea, ammonium sulphate, super-phosphates, and mixed fertilizers” (pp. 115–116), all to compensate for the soil’s supposed lack of chemicals essential to plant growth.

The logging of teak was to increase, for the low rate of harvesting during the war meant that the limits consistent with good conservation practice could be exceeded for a decade or so. Many other woods could also be harvested more heavily, and it was recommended that mechanical equipment be introduced to supplement the use of trained elephants. Access roads cut through the jungle would allow an “uninterrupted flow from forest to sawmill” (p. 57). In the seas, the significant expansion of fishing would justify the construction of a tuna cannery, and fish meal-, fish oil-, and cold storage plants. The average Burman, it was lamented, ate only twenty-four pounds of fish annually, compared with seventy-five pounds in Japan.

In transport, only through a massive overhaul of road, rail, and water, keeping pace with agriculture, industry, mining, and forestry, could the “New Burma” become modern. This included repair of the badly damaged rail system and the establishment of 3,500 miles of new secondary, farm-to-market roads.

For industrial development, priority was to be given to the production of the primary products and materials necessary for the Development Program. At present, “[m]anufacturing industry in Burma is in a very early stage. Much of it is confined to small-scale cottage industries, producing a narrow range of products by crude methods and with very little modern machinery” (p. 103). With the development of industrial centers, especially at Rangoon, Akyab, and Myingyan, there would be further requirements in housing, health, and education for the new workers, “many of whom ultimately will move from the countryside to the towns to work in factories” (p. 107).

Evidently, there was much here to raise the eyebrows of one who had spent five years immersed in literatures that emphasized traditional wisdom and were critical of modern development. Thus could Schumacher write: “I am writing furiously to complete a great memorandum before the weekend. It is a spirited exposition of my theories of economic development which are somewhat at loggerheads—as you can imagine—with the childish things going on here, largely inspired by American consulting engineers.”Footnote 23 A fortnight later, he wrote of having dinner with his “Gegnerspieler” [i.e., opponent],

the great Robert R. Nathan from Washington, who maintains seven economists here as Economic Advisors to the Government, whose work I am supposed to be able to evaluate and judge. My opinion is that they have given a lot of good advice and have also done a lot of damage (because they are all American materialists without any understanding for [sic] the precious heritage of a Buddhist country).Footnote 24

Life among the Buddhists

Since his arrival in Rangoon, Schumacher had been discovering life in a Buddhist society. His eyes had been opened by his Rangoon host, U Win, Minister of National Planning and Religious Affairs—“a big cheerful fellow, very cultured, who used to be a close friend of Gandhi’s and was present at G.’s assassination.”Footnote 25 One evening, U Win took him to a grand gala performance that had previously been put on for a state visit by Marshall Tito. Schumacher was moved by the gaiety and laughter of all involved, even the musicians. The next day, U Win took him to something even more impressive: the site of the sixth Buddhist Congress then taking place in Rangoon. It was an event so overwhelming that Schumacher found it too much to describe. In a short period of less than a year, the Burmese had constructed a giant artificial cave and accommodation buildings for a two-year congress that had begun in 1954 (see Figures 2-5).Footnote 26 From dozens of countries, thousands of Therevada Buddhists had flocked to Rangoon, in order to read, check, and amend the sacred texts. There were numerous interventions, including the expression of good wishes from foreign leaders and dignitaries.

Figure 2. The Maha Pasana Guha, or Great Sacred Cave.

Courtesy: Pariyatti, Onalaska, Washington

Figure 3. The Chattha Sangayana.

Courtesy: Pariyatti, Onalaska, Washington

Figure 4. The Chattha Sangayana.

Courtesy: Pariyatti, Onalaska, Washington

Figure 5. Honorable U Win, Minister for National Planning and Religious Affairs, addresses the Chattha Sangayana.

Source: The Chattha Sangayana Souvenir Album, Union Buddhist Sasana Council, 1956

In time, Schumacher became aware of distinctions amongst the Burmese. Telling his wife about a new acquaintance of his, civil servant U Ko Ko Jyi, he reassured her that he was not the head of a school of astrology but rather a member of the College of Astrologers—whose job was to tell the government whether the day was suitable or not for a particular undertaking.Footnote 27 He also noted that U Ko Ko Jyi was a traditionalist, a group, despised by the Westerners, such as U Hla Maung, who resented it if foreign visitors were seen even to be taking any notice of them.

In the weeks leading up to Burma, as part of his broader quest, Schumacher had taken up yoga, and he now felt the beneficial effects of his daily routine. “I get up about 6.45am and faithfully do my exercises from about 7 to 8, seldom less than an hour. I think it is due to Yoga that I have taken the change of climate (and of everything else) without any disturbance of any kind.”Footnote 28 Again on February 6, he writes of “doing my exercises diligently every day, now 20 weeks. I firmly believe that my wellbeing, mental and physical, without frequent tropical disturbances, is owed to Mr. Yesudian.”Footnote 29

After a month, Rangoon had become a special place. To Muschi, he wrote about wild birds coming and going in the hall and rooms of the Kanbawza Palace, unafraid because no one ever harmed them. In the city streets, the stray dogs roamed about freely and no one ever harmed them, either. His own driver was a “wild-eyed, barefooted Indian” who drove alarmingly fast through the streets, but “nothing happens because people invariably move with the most complete calm; there is no nervous, hasty pushing and jumping about.”

There are no beggars in Burma, except of course the yellow-robed monks who go from door to door (but never accost anyone). Both men and women wear long skirts down to their ankles, very colourful and gay. Buddhism is the life and soul of the country, and I have already met some remarkable Buddhists. I shall tell you more about them soon.Footnote 30

Two such Buddhists were, in fact, fellow Germans. The first was Georg Krauskopf, a youthful sixty-year-old school caretaker in Stuttgart and a Buddhist of forty years’ standing. When Schumacher met him in Rangoon, Krauskopf had just finished a course and, strained and exhausted, was delighted to meet a compatriot. They spent a week together, during which they evidently had much to discuss. Krauskopf had written a 1949 book on Buddhism, Die Heilslehre des Buddha (The Healing Teachings of the Buddha), which he had sent to Carl Jung. The latter had responded with an interesting letter in December 1949, reiterating his skepticism about the compatibility of Buddhist spirituality and Western consciousness.Footnote 31 In 1953, Krauskopf had been one of the hosts of a Ceylonese Buddhist deputation to Germany, instigated by the German expatriate Buddhist monk Nyanatiloka, amongst others, designed to promote the spread of Buddhism in that country.Footnote 32 After this week in Rangoon with Krauskopf, Schumacher could report that “I have learned many things from him which it would have taken me months to discover otherwise. . . . As a parting gift I gave him a little bronze Buddha-statue, made by the best silversmith of Rangoon, and he was as pleased as anyone could be.”Footnote 33

It may have been through Krauskopf that Schumacher met another compatriot, the ethnologist and photographer Gulla Pfeffer Kell (1887–1967), an “astonishing ‘witch’ aged 60,” who opened further doors for him.Footnote 34 By a remarkable coincidence, her path had overlapped with his own. She had

emigrated to England, British nationality, lived for 2 years at Coombe Springs (Bennett’s place) (!!), discovered Buddhism, came here to go through the Satipatthana School, now lecturer for Germanistik [sic] at Rangoon University. . . . What she tells about goings-on at Coombe Springs is absolutely devastating and proves that your instinct on that Sunday when we went there was sounder than my judgement. She admits, however, that one can can learn a great deal from Mr. B[ennett] and that there is a very great deal of truth in the teaching which G[urdjieff], she claims, obtained from a monastery in Upper Burma. Only Coombe Springs and the presumed influence Mr. & Mrs. B. establish among people there, she considers dangerous and evil. If you should see the Essames and if you can find a gentle way of doing so, please warn them against getting too deeply involved at Coombe Springs. It is indeed hard to find a fruit without a maggot in it!Footnote 35

By early February, Schumacher was well settled and treating it as an “extraordinary gift” to be in the East, after “four or five years of preparation.” He was making important new acquaintances:

Among the Europeans and Americans I have made many friendly relations, and I am regarded—I am reporting this objectively and without conceit—with a certain astonished reverence because I at least have some notion about what one encounters here. I am always being questioned with great and benevolent interest, and give information to the best of my ability. Gradually I am also winning over the Burmese, who may become friends.Footnote 36

Notwithstanding his years of reading, his letters reveal that he was only now discovering Buddhism as a living force, and doing so with one foot still in the world of Gurdjieff:

What we in England call “Work” is everywhere here a living thing, and they are only too willing to help. Yet one is by no means required to become a Buddhist: the true Buddhist has great veneration for Christianity, if it is genuine, and welcomes as his companions anyone who is at all “on the Path”. This attitude and this courtesy are what make me most happy here. (ibid.)

It was thanks to an introduction from the head of the Central Bank that he came in contact with U Ba Khin, a meditation master:

[Khin] was very friendly and interested; I simply said that while I had studied very much, I had achieved little practically, and he encouraged me. I have no doubt that the man has reached a very high degree of development, and that his only aim is to help other people, and particularly westerners. Have no fear that he simply wants to turn people into monks or nuns; he himself is not a monk, but despite his retirement still has both feet in professional life. (ibid.)

Not a monk indeed, U Ba Khin (1899–1971) was formerly the accountant general of Burma, and now head of the State Agricultural Marketing Board and advisor to the prime minister. In 1952, in Rangoon’s Golden Valley neighborhood, he had established the International Meditation Centre, devoted to teaching the Vipassana method. Its central shrine room was surrounded by eight connecting chambers from which meditating students could communicate with the master (see Figure 6).Footnote 37

Figure 6. U Ba Khin

Courtesy: Vipassana Research Institute, Igatpuri, Maharashtra, India

Following the classical Buddhist tradition, Khin’s training had three parts: sîla (morality), samâdhi (concentration), and panna (wisdom or insight), which together constituted the Eightfold Path.Footnote 38 Sîla involved the observation of Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood, and included refraining from killing any sentient being, stealing, sexual activity, and the consumption of alcohol. Samâdhi, which involved Right Exertion, Right Attentiveness, and Right Concentration, concerned the particular meditation technique taught by Khin for bringing tranquility of mind. This involved concentrating, not on a particular phrase or on an inner light, as in other methods, but on the point beneath the nose where the breath enters and leaves the body. With sufficient concentration, the student could achieve “one-pointedness,” or the complete reduction of perception and sensation to this minute breathing action. In time, with sufficient mastery of samâdhi, the novice could eventually hope to achieve panna, or insight, which involves Right Aspiration and Right Understanding. With true insight, the student begins to become aware of the impermanence of all things and gradually reaches a state beyond suffering: free of the ego, of doubts, and of attachment to rules, beyond passion and anger. Ultimately, he can attain the final goal of becoming an Arahat, achieving Nibbânic Peace Within.

Although it was customary for foreign visitors to attend a full ten-day retreat with U Ba Khin, he also received visitors on Sunday for lessons and consultations. Schumacher appears to have attended weekend classes at the center for a short period. On February 21, he wrote that, even if he was being neglected in his capacity as an economic advisor, he was “learning a lot from Burma.” Once again, his remarks on Buddhist meditation are from the perspective of the Fourth Way:

I find that the G./O. [i.e., Gurdjieff/Ouspensky] teaching, particularly as given in Nicoll’s Commentaries, is remarkably accurate. ‘Self-remembering’ is identical (as far as I can see) with ‘Sattipatthana’ [i.e., the achievement of mindfulness] as it is being taught here. I have made very interesting discoveries about the precise method of teaching.Footnote 39

He continued to reassure his wife:

You say for instance that my interest in Buddhism is imposing a new strain upon you, but please, Muschilein, there is no conceivable cause of strain in this, my sole motive and interest in Buddhism is in getting rid of all sorts of weaknesses and defilements in my character—of all the things that really could impose strain upon you and others.Footnote 40

By March 2, however, after what could have been only a few meetings, it appears that, although now practicing meditation, he had finished with U Ba Khin:

I take some time to myself every day, to do Yoga and Satipatthana (which is the same as Bennett’s ¼ hour, only better and longer). I am also reading the Gospels. I am very pleased indeed that you have discovered Meister Eckhart. A master indeed, as you say. The ‘master’ whom I met here I have not seen again. I wasn’t quite satisfied. But I keep meeting very interesting people, who can tell me a lot.Footnote 41

Perhaps it was here, as he let go of U Ba Khin, that Schumacher realized that, for all his reading, he was not and would never be a true Buddhist—that he was interested in Vipassana, the “Work,” and yoga, and their transcendental promise, but that, unlike Nyanatiloka or Krauskopf, he was not cut out for the life of austere detachment and simplicity required of the true follower of Siddartha.Footnote 42

Nonetheless, Buddhist society continued to make an impression on him. The great Schwedagon Pagoda: “all covered in gold. Imagine the moonlight on it and the gaily dressed crowds milling around. You can’t get inside it: it is solid. It towers above everything else. You can only approach it barefooted.”Footnote 43 A nocturnal festival in the Burmese countryside:

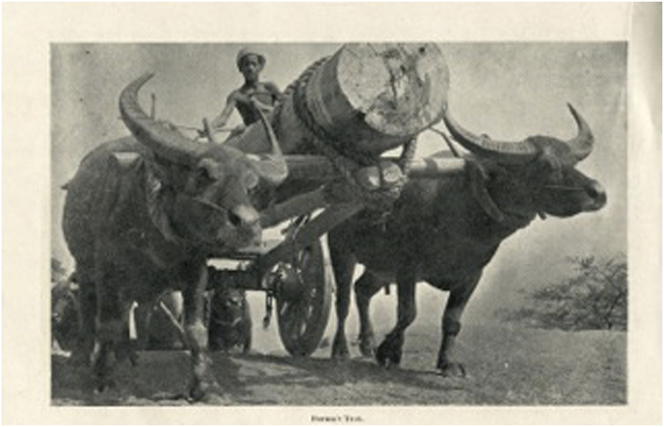

We arrived in pitch darkness after an adventurous journey over the most miserable roads and entered an enormous bamboo hut full of hundreds and hundreds of people aged 100 days to 100 years. Having taken off our shoes we squatted amongst them and watched the most astonishing and beautiful dancing accompanied by deafening music. Loads of cigars, tea, garlic, beans, and Burmese sweets were put before us; everybody was most hospitable and delightful, and the children rolled on the floor with laughter at our funny looks, funny dress and (to them) absurd behaviour. It is quite impossible to describe how nice and happy these people are. After several hours we were taken to one of the large wooden houses in the village where they gave us a stupendous meal, consisting of corn, rice, coconuts, salads, crabs and lobster and a thousand other things impossible to identify. At about midnight we were told: “Now let’s go to the big show!” After a long walk through the wilderness we got to the paddy-fields (which are empty at this time of the year). A stage had been erected at one end, and there were at least 2 or 3000 people squatting around watching the all-night performance. They had come on ox-carts, and the oxen and dows [sic; likely “cows”] were squatting peacefully between them, or on every kind of vehicle; some were sleeping, some were watching, some were having a meal at one of the innumerable improvised little eating places; all were set to stay the whole night, except us. We had a cup of coffee somewhere under the moonlit sky and then gently got ready to go home. This was the orient indeed. While we were enjoying the mild coolness of the night, the local population were all wrapped up in blankets etc. shivering in the intense winter cold. But you saw nothing but cheerful faces, well-fed people in gaily-coloured dresses, and—of course—not a single beggar. When some of the American ladies in their extremely thin garments seemed to find it a bit cool, the villagers immediately brought some blankets and never even stopped to consider whether or when they would get them back. We got home at about 2a.m.—a memorable excursion!Footnote 44

Figure 7. Burmese ox cart drawing teak.

Source: Burma. A Handbook (Union of Burma, Ministry of Information, 1954, p. 32)

Naturally, the more he opened himself to Burma, the more he perceived foreign influence as a threat. Writing of a party at the Kanbawza Palace for the Chinese Cultural Mission, he lamented the fact that the dress, food, plates, and cutlery were all Western. When he met some Burmese artists, one said that he painted in Burmese style for Western customers, and in Western style for the Burmese.

A most significant remark! The whole Orient is coming out in Western spots, and, as Conze said, in another 20 years, maybe, the only true Orientals left will be a small number of Europeans and possibly Americans…. There is no doubt, the West, even though its days of power in Asia are gone, has won all along the line and is winning more every day. Mr. Copmall is going to introduce “modern art”; horror comics are already in Burmese, ghastly American films are starting and given from advertisements all over the place, and “industrialization” is doing the rest.Footnote 45

His job as economic consultant was bringing him into direct contact with these forces of Westernization and industrialization: “My work is not easy. The U.S. economic advisors are very well entrenched and difficult to compete with. But my relations with them are excellent. So there will be no unpleasantness. I don’t agree with a lot of the advice they have given, but it will not be easy to challenge them successfully. Wir werden sehen.”Footnote 46

“Economics in a Buddhist Country”

As mandated by the UN, Schumacher completed his “Strictly Confidential” report on the Burmese plan, submitting it at the end of March. It is made up of a short introductory summary and four appendices.Footnote 47 Put briefly, he found the Nathan plan to give too much emphasis to “accessories,” such as transport, communications, and electrification, and not enough to “truly productive investment,” viz., agriculture, irrigation, forestry, mining, and manufacturing. When the goods were there, he implied, then the infrastructure could follow. Electrification was “without question a rich man’s privilege [which] truly belongs to a later stage in economic development” (App. II, p. 4). The infrastructural spending should thus be stretched over twice the envisaged period and funding for productive activities increased, with no neglect of “small-scale industry” (emphasis in original). As for the external sector, he disagreed with the proposed liberalization of imports. If indigenous production was to thrive, there must be protective tariffs.

Burma should also reduce foreign influence on its economic affairs, which would allow less use of “an arithmetical approach to problems which are essentially matters of empirical judgement and common sense. ... Unnecessary complications and harmful sophistication” were to be avoided (p. 3). Economic policy making, said Schumacher, required a simple, not complex, approach, with the main economic data gathering concentrating on rice, foreign receipts, and expenditures, and two or three price indices. Progress reports should be compiled by government employees rather than foreign consultants, who, in his opinion, were far too involved at the operational level.

Thus went his dispassionate official report as UN consultant. Privately, however, in February, prompted by what he was witnessing and piqued by official neglect, he sat down and privately put his true thoughts on paper. “Economics in a Buddhist Country” not only questions the appropriateness of Burma’s aims, but becomes a sustained incantation on economics, culture, and human well-being. Five years of rumination on materialism and modernity irrupt into the professional sphere (see Figure 8).Footnote 48

Figure 8. From “Buddhist Economics” handwritten draft.

Courtesy: Schumacher Center for a New Economics, Gt. Barrington, MA

Given the variety of people’s ideas of the purpose and meaning of life, he writes, it is astonishing that there should be only one body of thought termed “economics.” What is currently accepted as the science of economics is rooted in the outlook of the materialist. It is reasonable to emphasize material economic concerns up to a point, but it is inappropriate that questions of “meaning and purpose” be neglected entirely. If they are, it is because the science of economics arose only in the West, and at a time when Western materialism ruled supreme. Non-materialists have been too weak to think out the matters for themselves, he says, and have been too ready to accept the “spurious claims” of the Western economists (p. 2).

The essence of materialism, says Schumacher, lies in the absence of any idea of “limit or measure.” Quoting without citation the official Burmese plan on the possibility of endless growth,Footnote 49 he says that such an attitude is incompatible with Buddhism or Christianity or with anything proclaimed by the “Great Teachers of mankind.” The ignorance of limits, whether found to the east or the west of the Iron Curtain, constitutes the “Economics of Materialism.” When will it be realized that it is incompatible with the Buddhist way of life? When will it be realized that other systems of economics are possible, and even available, if only in embryonic form?

An example of an economics not entirely given over to materialism, says Schumacher, was available in the work of Gandhi, the “greatest man of our age.”Footnote 50 Gandhi laid a foundation for economics that would be compatible with Hinduism and Buddhism, based the concepts of Swadeshi and Khaddar. The first was essentially an adjunct to buy “locally.” Gandhi wrote:

In your village you are bound to support your village barber to the exclusion of the finished barber who may come to you from Madras. If you find it necessary that your village barber should reach the attainments of the barber from Madras you may train him to that. Send him to Madras by all means, if you wish, in order that he may learn his calling. Until you do that you are not justified in going to another barber. That is Swadeshi. (p. 4)Footnote 51

Gandhi admitted that such an approach might be the source of hardship and denial, but said it was a “religious principle” to be followed without regard for discomfort. As for Khaddar, it was the vow to spin with one’s own hands and wear only homespun garments, thereby realizing the dignity of labor. Not even formal education, said Gandhi, was sufficient reason for an individual’s complete abandonment of manual labor and craftsmanship. Quoting visitors to Gandhi’s ashram:

When we thought of the whole atmosphere of the place and the ideals for which it stands—the joy of the workers in their work, the happy, contented homes, the education available to the children, the absence of any anxious thought for the morrow—our hearts ached to think that we were to leave it all so soon. Here, more than ever before in our busy lives, have we felt the truth of the words “Laborare est orare”—to labour is to pray. (p. 5)

Although Swadeshi and Khaddar were not necessarily the only points of departure for a system of “Buddhist Economics,” says Schumacher, it was economics nonetheless and it was diametrically opposed to the economics of materialism. The latter said, ‘Labor is an item of cost—a disutility’; the former said, ‘To labor is to pray.’

At this stage, when the non-materialists are still so very weak and so very trusting, it is merely my concern to plea [sic] with the professors and students of economics—and with the statesmen as well—that they should study and listen to the Mahatma’s economics with as much attention as they now give exclusively to the Economics of Materialism. (p. 5)

For Burma to employ Western economic advisors, he said, meant importing an economics derived from the materialist understanding of life. To accept the Western expert’s recommendation that transport prices be made lower for longer hauls was essentially to promote “urbanisation, specialisation beyond the point of human integrity, the growth of a rootless proletariat,—in short, a most undesirable and uneconomic way of life” (pp. 6–7). The recommendation to maximize exports, or to restrict imports, also had implications for ways of living.

When, then, will someone get down to it and develop a system of thought that would deserve to be called Buddhist Economics? This is a very urgent need. Let no one conclude from what I have said that nothing could be done, or nothing should be done, for the economic development of Burma; that all development would necessarily clash with and undermine the Buddhist way of life. It is the type and direction of ‘development’ that I am talking about. If you want to become materialists, follow the way shown by Western Economics; if you want to remain Buddhists, find your own ‘Middle Way.’ (p. 7)

This meant defining certain “limits.” Material things were important only up to a point. If economic conditions could be broadly classed as corresponding to misery, sufficiency, or surfeit, then only the second of these was good. “Economic ‘progress’ is good only to the point of sufficiency: beyond that, it is evil, destructive, uneconomic” (ibid.).

Drawing the distinction between ‘renewable’ and ‘non-renewable’ resources, he says that a civilization built on the former cooperated with nature, whereas one built on the latter bore the “sign of death” (p. 8). “It is already certain beyond any possibility of doubt that the ‘Oil-Coal-Metal-Economies’ cannot be anything else but a short abnormality in the history of mankind—because they are based on non-renewable resources and because, being purely materialist, they recognize no limits” (ibid.). As for the frantic development of atomic energy, it was merely a violent attempt to escape fate, and to attempt to do it on a scale adequate to replacing coal and oil was a prospect “even more appalling than the Atomic or Hydrogen bomb.”

The Economics that I have in mind would recognise other differences in the value of materials than differences in price. It would recognise for instance that wood is noble while iron is ignoble—a strange thought for modern men.… It would recognise that some materials lead to a simple and satisfactory pattern of life, while other materials lead to a complicated, oppressive and therefore unsatisfactory pattern of life. It would recover a notion of quality that is unknown and in fact incomprehensible to the men of machine civilisation. (p. 8)

…

Impermanent are all created things, but some are less impermanent than others. Any system of thought that recognises no limits can manifest itself only in extremely impermanent creations. This is the great charge to be laid against Materialism and its offspring, modern Economics, that they recognise no limits and, in addition, would be incapable of observing them if they did. This is the terror of the situation. (pp. 8–9)

The answer lay in “[s]elf-imposed limits, voluntary restraint, conscious limitation,” for these were “life-giving and life-preserving forces.” A New Economics would be “based on the recognition that there were limits to the possibility and desirability of economic progress, the complication of life, the pursuit of efficiency, the use of non-renewable resources, specialization, and the substitution of the ‘scientific method’ for common sense…. Yes, indeed,” he concludes, “the New Economics would be a veritable ‘Statute of Limitation’—and that means a Statute of Liberation. May All Beings Be Happy” (p. 9).

* * *

Schumacher’s official report appears to have had little impact in Rangoon. In mid-March, he thought he noticed some “Schumacherisms” in the prime minister’s latest speech, and felt that his ideas had affected trade policy, but, to his disappointment, there was no call to meet with the leader.Footnote 52 Only the Americans around Nathan showed their disgruntlement with him for criticizing their ideas. His renegade essay, however, would have a different trajectory.

IV. THE ECONOMIST AS TRADITIONALIST CRITIC

The decade after Burma was a momentous one for Schumacher. Most significantly, his wife Anna Maria, who had settled only reluctantly in England and had observed with anxiety the spiritual wanderings of her husband, passed away in 1960, leaving behind four children. Schumacher soon remarried and, with the help of his second wife, Verena, with whom he would go on to have four more children, in time restored equilibrium to life at Holcombe.

After Burma, his “Economics in a Buddhist Country” was first noticed in India by Jaya Prakash Narayan, socialist-turned-Gandhian, and published as an appendix to his (1959) A Plea for the Restoration of Indian Polity, a book that argued for the return of the village order destroyed by imperialism.Footnote 53 Two years later, it appeared in The Roots of Economic Growth, a collection of talks given by Schumacher on his first visit to India, published in Varanasi.Footnote 54

By that time, thanks to continued reading and to his contact with the Gandhians, Schumacher’s knowledge of the Mahatma’s economic philosophy was growing. Two important influences here were Richard B. Gregg (1885–1974), the American disciple of Gandhi; and Joseph Kumarappa (1892–1960), the Gandhian economist. Among Kumarappa’s many books was his Economy of Permanence, originally published in 1945, which, in the context of planning the future of an independent India, provided an extensive discussion of “permanence,” later called “sustainability.” As for Gregg, another remarkable figure, in a series of books, including Which Way Lies Hope? ([1952] 1957) and A Philosophy of Indian Economic Development (1958), he provided many elements of the philosophy later promoted by Schumacher. This includes the emphasis on ensuring that people have work rather than ensuring maximal productivity; the physical and psychological benefits of manual, and especially craft, labor; the need to control the use of power-driven machinery, given that it replaces human labor and relies on the use of non-renewable resources for its operation; the idea that the consumption of “stored” solar energy, in the form of coal and oil, is both “sinful” and unsustainable; and the benefits of decentralization and small-scale production.

By the early 1960s, Schumacher was assimilating such work and drawing on his knowledge of energy to extend his critical approach to the West.Footnote 55 For example, in 1960, in “Non-Violent Economics” in The Observer, he argued that the existence of a nuclear arsenal had made non-violence an imperative, and that the Western economic system was necessarily impermanent: “A way of life that ever more rapidly depletes the power of the earth to sustain it and piles up ever more insoluble problems for each succeeding generation can only be called ‘violent’” (p. 11). In a 1963 review of Robert L. Heilbroner’s The Great Ascent, he wrote that the spread of the Western market economy, through development aid, was destroying the ancestral cultural and spiritual capital on which all civilization was based, and offering nothing to put in its place.Footnote 56 Schumacher became an ardent critic of the World Bank under director Eugene Black, whom he viewed as an agent of such destruction. Going beyond words to action, in the mid-1960s, he formed the Intermediate Technology Development Group in order to promote development in the Third World through the use, not of the massive infrastructural and industrial projects promoted by the World Bank, but of relatively simple and affordable tools and equipment.

In 1965, he wrote a new “Buddhist Economics,” clearly inspired by the Rangoon essay and bearing its original title. Though carrying the same message, it now addressed the Eastern and Western reader, and it reflected the gathering influences upon Schumacher. He invokes Ananda Coomaraswamy’s (Reference Coomaraswamy1912) Art and Swadeshi on the distinction between tools and machines, noting that the latter tend to be destructive of culture.Footnote 57 He cites Kumarappa in defense of a Buddhist understanding of labor as a constructive human activity rather than a source of disutility. He contrasts Buddhist economics, which promotes the satisfaction of needs through a minimum of consumption, with conventional economics, which emphasizes the extension of consumption. He suggests that local production for local needs is less likely to give rise to violent competition for resources than is large-scale production. Thanks to Gregg (Reference Gregg1958), he cites Bertrand de Jouvenel on Western man’s neglect of his natural surroundings, in particular of trees and water. A Buddhist economist, says Schumacher, would emphasize the planting of trees.Footnote 58 Given that modernization and the pursuit of material wealth are leading to unhappiness, he says, there is a need for a Middle Way, between the traditionalist immobility of India and the heedless materialism of the West—a Right Livelihood based on simpler, less violent methods.

Initially buried in an 800-page, multi-authored compendium of essays on Asia in 1965,Footnote 59 “Buddhist Economics” was then reprinted in the first issue of Resurgence (1966) and the American magazine Manas (1969). While, here, Schumacher was preaching to the converted, his inclusion of it in his 1973 collection, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered, extended its reach. Collecting essays and lectures from the previous decade, that book called for greater decentralization in government and economic organization; the development of local, as opposed to global, economies; the use of intermediate technology in developing countries; the relinquishment of nuclear technology; and the promotion of organic agriculture. As much the work of a social philosopher as an economist, the book made a sustained appeal for the adoption, by individuals and households, of simpler lifestyles, with lower environmental impact. In mainstream eyes the work of a misguided heretic, the book unexpectedly touched many readers concerned by cultural loss, environmental destruction, and the harmful effects of technology. For most of them, it is safe to say, the touchstone chapter was “Buddhist Economics.” Reprinted countless times since then, it remains synonymous with Schumacher’s name.

V. CONCLUDING REMARKS

A conventional economist until the end of his thirties, on the foot of the German wartime experience, E. F. Schumacher underwent a deep mid-life change in personal philosophy. Beginning around 1950, this expressed itself in the form of his involvement in, variously, gardening and the emerging “organic” movement; the esoteric world of G. I. Gurdjieff; and the domains of Eastern philosophy and religion, through which he developed a particular interest in Buddhism.Footnote 60 These explorations carried him to Burma in 1955, ostensibly to evaluate that country’s new plan for economic development, but also to discover life in a Buddhist society. Those three months in Rangoon proved pivotal, for while they did not see him convert to Buddhism, they opened his eyes to the richness of Buddhist culture and obliged him to start reconciling his economic thinking with his new philosophical outlook. He began with “Economics in a Buddhist Country,” a rebellious private essay, written in Rangoon, catalyzed by the Western threat.

The Burmese experience shaped Schumacher’s work thereafter. His “Buddhist” essay marked him as a defiant critic and provided him with an entrée to India and post-Gandhian debates there on economic development. This led to his having something of a double existence from then on: as Coal Board technocrat on the one hand and heterodox activist on the other. In debates on development, resources, and technology, the Buddhist edicts of non-violence, conscious limitation, and voluntary restraint became an essential refrain in his message, to both the East and the West. Economies that relied upon violent technologies, be they nuclear or agricultural; upon non-renewable and therefore exhaustible resources; upon rural depopulation and urban sprawl; or upon soul-destroying work were neither sustainable in the long run nor worthy of imitation by “developing” countries. This assessment informed his essays, lectures, and work on intermediate technology in the 1960s, and his famous book of 1973.

If he did not become a practicing Buddhist, what, then, did Schumacher “become”? After Burma, for some years he followed classes on comparative religion with Edward Conze and he appears to have remained close for a while to the Gurdjieffian world. More durably, from the mid-1950s on, he deepened his study of the Traditionalist literature to which Coomaraswamy had been an introduction, reading the work of René Guénon, Frithjof Schuon, and their followers. Traditionalism regarded the entire modern era since Descartes as a period of deviation, during which a part of humanity, under the influence of science, technology, reason, and democracy, had forgotten its timeless dependence upon a divine power. The Traditionalists also regarded the world’s great religions as being various expressions of this single primordial truth concerning man’s place in the cosmos; a truth still acknowledged in traditional societies but forgotten by a decadent West.Footnote 61

Schumacher embraced, if not the radical anti-Enlightenment form of Traditionalism, then at least a mild version, finding therein a congenial metaphysical underpinning for his continued critique of “progress.” For the rest of his life, in his lectures and writings, he would refer, often allusively, to the ideas of Coomaraswamy, Guénon, and Schuon. The Traditionalist philosophy was congruent with what he had observed in Burma; with his efforts in the 1960s to promote simple, rather than sophisticated, technology; and with his judgment that Western “economism” was destroying Eastern culture. It was also coherent with his own eventual conversion, in 1970, to one of the great religions, Roman Catholicism. His diminutive final book, A Guide for the Perplexed (1977), was not only heavily influenced by Traditionalism but was regarded by Schumacher as the culmination of his life’s work.Footnote 62 Be that as it may, he is best remembered for his humanistic critique of modern economic development, catalyzed by his time in a Buddhist society.