When, in 1865, Richard Jones Berwyn leapt from the ship Mimosa and landed on the beach in what was to become Puerto Madryn (Patagonia) he was fulfilling a personal and national dream that was embedded in global dynamics. Determined to be the first of the first contingent to set foot in this Welsh ‘New World’, Berwyn was filled with hope for a new Welsh Heimat, or utopian homeland. Here, in the words of the preacher Abraham Matthews, who was also aboard the ship, they could re-found Wales

in an empty country, without being under a state government … where the Welsh could settle and rule themselves and ensure the continuation of their national habits … and establish the kernel of a Welsh Government … [with] a Welsh population, Welsh schools and complete enough possession of the country so that they would not be swallowed up by other nations round about.Footnote 1

The community they founded in the Chubut Valley, known as Y Wladfa (The Colony), thus engenders a paradox that this article seeks to explore: that people who felt their nation to be stripped of sovereignty, socially disparaged, culturally quashed, and in many ways colonized, should choose as their key strategy the creation of a new homeland through an act of colonization. This leads to the questions: how can a social group be simultaneously colonizers and colonized? How does this shape settler relationships? And what might we learn about settler colonialism by studying this ambiguous position? These are the key questions that the article will address. The search for a response involves integrating elements more commonly associated with migration studies: researching the ‘home’ context of settler life before embarkation, and studying the global context that shaped this particular settlement.Footnote 2

This article is the first to analyse Welsh Patagonia from a global perspective. It makes three key contributions to the field. First, it reveals how ambiguities within the Welsh–indigenous relationship stemmed from their subordinate position in both their ‘home’ setting and the settler setting. The Welsh were ‘colonizers’, but from a colonized position. As settlers in Argentina, they benefitted from geopolitical hierarchies of race and civilization, even while they suffered indignity in the face of the same discourse at home, and were constrained and disdained by a domineering state in Britain, and eventually in Argentina. Secondly, it argues that, despite seeming to be an ‘outlier’ case of the British World, Y Wladfa is far from parochial. Indeed, research reveals the centrality of global connections. The initiative began in Ohio, was debated in Melbourne, and was framed by an ideological critique of both global and local imperial politics. Thirdly, then, it suggests important methodological insights that have theoretical implications, in that both the ‘back story’ and the global context of settlement need to be taken seriously. To understand why these colonists created this settler society in this place, we must pay attention to their motivations, and therefore to the ‘home’ setting. This case should be placed within wider dynamics, which were linked to the British World, global patterns of migration, and colonial discourses of civilization and barbarism. As a result, the article not only contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the Welsh Patagonian venture, but also suggests the insights that a fresh methodological perspective might bring to understanding other settler societies, and to complicating settler theories.Footnote 3

The article is divided into two sections, following a short discussion of context and theory. The first examines the Welsh case as a colonized subjectivity, discussing the racialized logics that constrained Welsh political autonomy and disparaged Welsh culture, the global reach of such logics, and the resistance movements that created Y Wladfa. The second section explores the Welsh as colonizers, highlighting their strategic role in Argentina’s nation-building project and their reiteration of European superiority. The ambiguity of their relationship as both colonizer and colonized is explored, focusing on the relationships of dependency and affinity with their indigenous neighbours, and their subordination as an ‘independent’ group of settlers to the Argentine state. Overall, I argue that nuanced analysis of the settler colonial condition requires a move beyond binary and linear approaches to settler colonialism. Thinking from a location peripheral to metropolitan power, and from a multi-sited, global perspective, is a core strategy in achieving this aim.

Introducing Y Wladfa

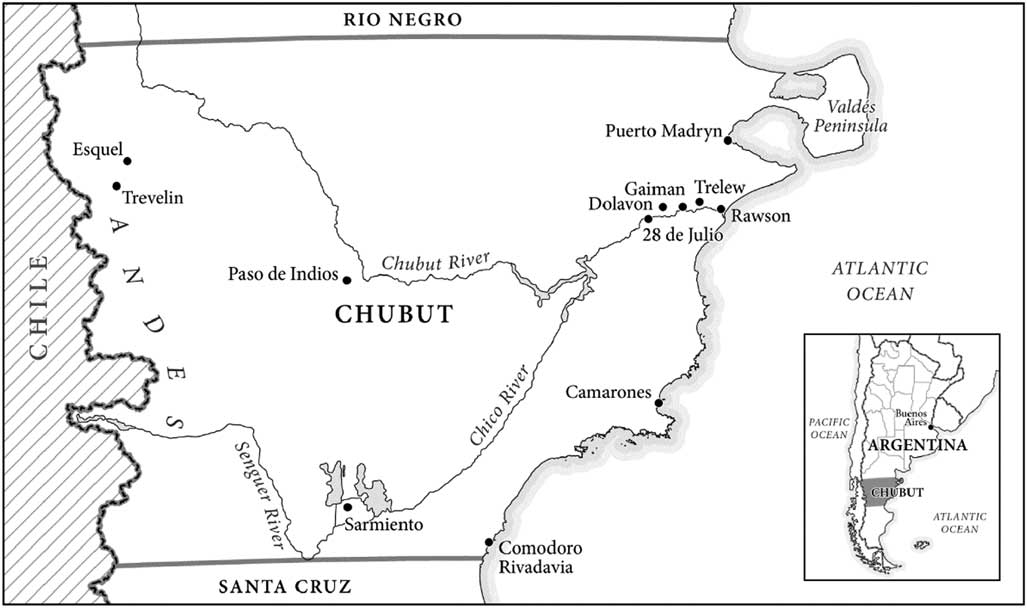

The driving force behind Y Wladfa was a preacher, nationalist, and social commentator, Michael D. Jones from Bala, mid Wales. Along with other campaigners, he founded the Colonizing Society in 1861, which organized a scouting visit to Patagonia, negotiated with the Argentine government for rights to the territory, and advocated Y Wladfa’s cause via lecture tours, newspaper articles, and the Handbook of the Welsh Colony.Footnote 4 The enterprise was controversial, and was hotly denounced as foolish or unpatriotic in the newspaper columns of Baner ac Amserau Cymru (The Banner and Times of Wales) and other publications. However, eventually, around 165 people landed on the beach on 28 July 1865, where Puerto Madryn stands today. Most had already migrated within Wales, or to England, in search of work, and they travelled as families. Like most settlers at that time, they were motivated by the push of poverty, and the pull of freedom and opportunity, but also by a nationalist political and cultural agenda.Footnote 5 After suffering arduous journeys and moments of crisis, the Welsh contingent settled on the banks of the Chubut river, eventually founding the towns of Gaiman, Trelew, and Rawson, which served the farms established on allotted plots (see Figure 1).Footnote 6

Figure 1 Welsh Patagonia. Source: Geraldine Lublin, Memoir and identity in Welsh Patagonia, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2017, p. ii.

These areas, and the wide hinterland beyond, were controlled by indigenous groups (Tehuelche, Pampa, and Mapuche), who journeyed in groups across the open plains to north and south, and up into the wooded Andes. They and the Welsh lived peaceably alongside one another, and learned a little of each other’s ways and languages, but they did not intermarry. Nor did the Welsh seek to rule over the indigenous peoples, or to promote their religion.Footnote 7 Rather, the memoirs describe their relationships as the sporadic intersection of parallel lives and ways of life, alongside mutual cultural curiosity.Footnote 8 Indeed, the Welsh saw a lot more of their indigenous neighbours than of the Argentine state during the first ten years, though Buenos Aires did provide occasional shipments of animals and goods.

Y Wladfa thus briefly enjoyed the autonomy and cultural integrity that the Welsh settlers craved. Essential to their success was trade with the nomadic indigenous communities of the region, who exchanged foodstuffs for skins of guanacos (wild relatives of llamas) and ‘ostrich’ (rhea) feathers, commodities that were sold on to Buenos Aires and then beyond.Footnote 9 This provided cash that was invested in the colonists’ farms, which, with the introduction of irrigation, became famous for their wheat production. This, in turn, financed the Cooperative Society (1885), a railway network (1889), and the Phoenix (gold) Mining Company (1893), as well as the building of chapels and schools.Footnote 10 Some Welsh settlers later migrated to the Andes in 1887, where they established the settlements of Trevelin and Esquel.

Politically, the Welsh remained self-governing until 1875, when Commissar Oneto arrived. Even then, they maintained significant autonomy until, in 1881, the newly appointed Commissar Finoquetto imposed rule from Buenos Aires. This move was consolidated by the arrival of the army’s ‘Conquest of the Desert’, and the imposition of Colonel Luis Fontana as governor in 1884.Footnote 11 Thereafter, the Welshness of the community was gradually eroded by its inclusion in Argentine nation-building initiatives, especially schooling. However, it retained the eisteddfodau (competitive cultural festivals), and many people continued to speak Welsh. The fact that other migrant communities began to arrive, especially Italian, Spanish, Syrian, and Jewish, further diluted this node of Welshness, as did the departure of some Welsh families to Canada and Australia.Footnote 12 However, centenary celebrations in 1965, the rise of tourism, and the resurgent Welsh-language movement and policy agenda since Welsh devolution, all served to maintain and then advance the ‘Welshness’ of the Chubut Valley, up to the present.Footnote 13

Y Wladfa has a symbolic significance for Wales that far outweighs the size of settlement. It represents proof of Welsh language endurance and the ‘righteousness’ of this colonial venture, themes which tap into key motifs of national identity today.Footnote 14 One effect has been to create a body of academic work that is accurate, detailed, and fascinating, but rather heroicized and narrow in scope. Within Welsh-speaking popular culture, Y Wladfa is often celebrated in idealized terms, and the nexus between Wales and Patagonia is commonly portrayed as an umbilical cord, largely untouched by wider global trends.Footnote 15 As a result, the settlement is seldom drawn into critical debates about settler colonialism, although Geraldine Lublin has begun this important work.Footnote 16 Nor is it viewed within the wider scope of nineteenth-century migration and settler colonialism, and the racial hierarchies that underpinned them. Globalizing Welsh Patagonia is a key aim of this research.

The ‘British World’ approach to empire studies underpins analysis of these global processes. However, this scholarship focuses on the ‘core’ of more populous settler colonies like Australia, while the ‘peripheral’ case of Y Wladfa seldom merits more than a passing mention.Footnote 17 Other British ‘political’ settlers also tend to be overlooked, such as the socialist Clarionettes, who migrated to New Zealand, or indeed William Lane’s attempt to create a ‘white’ working man’s paradise in Paraguay.Footnote 18 A better-known ‘nationalist’ settlement was the Scottish Darien initiative in Panama, in 1698, though this was motivated by the search for national wealth rather than cultural dignity and political autonomy.Footnote 19

Research on Welsh migrations does exist, but it focuses on large Anglophone settler colonies, such as Anne Kelly Knowles’s excellent study of migration and settlement in the USA, or Jerry Hunter’s work.Footnote 20 Indeed, most Welsh people did conform to the ‘core’ trends: the majority of migrants settled in Anglophone countries and were motivated by economic needs and desires.Footnote 21 Moreover, many Welsh people participated enthusiastically in the British empire, through which they gained a sense of pride, dignity, and elevated social standing. As Paul O’Leary argues, many espoused loyalty to the British state, seeing this as a mark of maturity and modernity, as well as expressing enthusiastic support for the crown.Footnote 22

The British World literature itself has begun to acknowledge the need to differentiate between the experiences of the ‘four nations’, as John Mackenzie’s article and Gary Magee and Andrew Thompson’s ambitious book attest.Footnote 23 However, it is notable that the Irish and Scottish experiences dominate accounts of the ‘other’ nations, in part because Welsh statistics and experiences were swallowed up by use of the ‘England-and-Wales’ category (much like other groups in England, such as the Cornish). The centrality of subordination ‘at home’ in motivating Y Wladfa is invisible to the ‘four nations’ approach, which disaggregates the migrants but overlooks the very real political and racialized hierarchies that shaped relationships in the home setting. Doing so, it continues the British World tendency, in the words of Rachel Bright and Andrew Dilley, to ‘[risk] neglecting a fundamental concern of imperial history in all its varieties: power’.Footnote 24 Thus not only is Wales peripheral to the core of British World scholarship, but Welsh political and cultural subordination within nineteenth-century Britain and its empire is also overlooked.

Two other layers of marginality come into play in the settler setting. First, the Argentine location is marginalized within Anglophone settler research, which is built upon experiences in the USA, Australia, and southern Africa. While James Belich’s important book does discuss Patagonia, the status of Argentina as an ‘informal’ component of the British empire places it at the margins of global economic flows and of his ‘Anglo-World’ thesis.Footnote 25 Patagonia itself, in turn, was marginal to the Argentine state, as Buenos Aires governed territories to the south of the Rio Negro in name only, even as late as 1865.

Thus, Welsh Patagonia was subject to multiple marginalities, making it a particularly insightful location from which to think about the wider dynamics of settler colonialism. Bright and Dilley rightly argue that the British World approach overlooks asymmetries of power between metropole and settler societies, as well as power inequalities between settlers and indigenous peoples. To this we can add, based on this case study, two other dimensions: skewed power relations within the ‘home’ setting, and enforced assimilation in the settler colony. The next task is to gather the conceptual tools that will help to make sense of this complex scenario.

Theorizing settler colonialism

Recent scholarship in the field of settler colonial studies has championed an important rethinking of colonialism in the last fifteen years or so. It has been inspired by the indigenous resurgence, both as a supportive counterpart to indigenous studies and as a medium for critiquing the historical and contemporary policies of settler states that address ‘the indigenous problem’.Footnote 26 It now boasts a journal (Settler Colonial Studies), a handbook, and a canon of work led by Lorenzo Veracini.Footnote 27 The field developed primarily in Australia and New Zealand, spreading out to Canada and the United States, and this emphasis on Anglophone experiences, and English language archives, has shaped its assumptions and examples.

The contemporary field revolves around Patrick Wolfe’s key article, in which he posits that settler colonialism is a fundamentally genocidal social and economic system, which requires the ‘elimination of the native’.Footnote 28 This is for two reasons, he argues: in order to free up land which can then be distributed to settlers, the new ‘citizens’ of the colony; and in order to remove alternative claims to sovereignty. This elimination takes the form of physical genocide sometimes, but also aggressive assimilation practices, which are orchestrated deliberately by the state on an ongoing basis. Thus, for him, ‘settler colonizers come to stay: invasion is a structure not an event’.Footnote 29 The emphasis on genocide lends his argument the kind of deep moral weight that makes settler colonialism hard to justify, and therefore promotes a specific and critical political agenda. However, his analysis posits a binary interpretation, which splits the settler colonial world into the colonizer and the colonized, imbuing agency in the colonizer and victimhood in the colonized. As a tool deployed to serve strategic essentialism, the accusation of genocide has huge political leverage, and the easy moral dichotomy makes for a compelling ethical argument against settler colonialism, as Wolfe argues in his piece ‘Recuperating binarism’.Footnote 30 However, while the ‘colonizer–colonized’ split may be politically effective, it can be intellectually simplistic.

Settler colonial theory attempts to make sense of these relationships of domination, emphasizing different aspects. Earlier iterations, like Donald Denoon’s pioneering study, took a political economy perspective. He compared settler regimes in a wide range of countries, including Argentina, and focused on global dynamics of trade, investment, and labour.Footnote 31 Recent work, led inspiringly by Lorenzo Veracini, has tended to focus on the actions and logics of the settler colonial regime, in the form of both metropolitan governments and settler states. This valuable work tempts us, however, to conflate state policy and the everyday responses of settlers themselves, and to homogenize settlers, their subjectivity, and their identity. Mark Rifkin’s important discussion of ‘settler common sense’ shifts the focus from the state to settlers, as people who have distinctive relationships to the regimes of law and administration that comprise the settler state. Yet his work continues to use a binary ‘separate worlds’ approach to theorize the settler colonial milieu, which sidelines indigenous agency and overlooks interaction.Footnote 32

By contrast, the wide range of archive-based, historical work on the everyday lives of settlers embraces complexity as a principle of settler identity and action. Research by ground-breaking scholars, such as Richard White and Colin Calloway for the Americas, and the authors of essays in Fiona Bateman and Lionel Pilkington’s edited collection, focus on the settler location as a social world, constituted by both settlers and indigenous people, and replete with complex power relations, transculturation, and intimacy.Footnote 33 This broadly postcolonial perspective, anchored in subaltern experiences, inspires the approach taken here. A wide divide exists, then, between theoretical work that focuses on the state, and empirical scholarship that foregrounds settler and indigenous experience.

To develop a critical yet nuanced analysis of how settler colonialism works, it is necessary to bring these two approaches together, exposing the deep injustices of colonialism, but also imagining that settlers occupy complex subject positions that are far from black and white. One way to inject complexity is to analyse from the margins of powerfulness, rather than the core. Importantly, periphery-thinking is not a celebration of parochialism. Rather, seemingly ‘obscure’ cases are made relevant by locating them within dominant global logics, and their meshwork of international connections. Starting the thought process ‘elsewhere’, moreover, shakes up assumptions, because thinking from the margins cracks open the binary (powerful colonizer/powerless colonized) right from the start.Footnote 34

In the Welsh Patagonian case, analysis requires us to understand how the Welsh can be simultaneously colonized and colonizing. The work of Alan Lawson (sometimes with Anna Johnston) offers some insight. Lawson configures the settler as a subject who occupies a Second World ‘caught between two First Worlds …: the originating world of Europe … and … that of the First Nations’.Footnote 35 He then argues suggestively that ‘the cultures of the Second World are both colonizing and colonized [in which] … there are always two kinds of authority and two kinds of authenticity that the settler subject is con/signed to desire and disavow’.Footnote 36 This configuration does aid understanding of the settler condition in the settler milieu, by explaining why, beyond practical need, settlers appropriate indigenous objects, names, or practices, as well as by identifying the anxieties associated with imitating the metropole and never quite achieving that standard.Footnote 37 Lawson and Johnston portray settlers in the colony as ‘European subjects [of a dominant, paternalist metropolitan state] but no longer European citizens’, and it is this that makes ‘the settler both colonized and colonizing’.Footnote 38

At this point settlers may rebel and make a claim to sovereignty, transforming the settler colony into a settler state. While this can explain the American Revolution of 1776, Lawson and Johnston make two important assumptions about settlers as people: they imagine them, first, to be a homogeneous grouping, and, second, to have had an unproblematic relationship to the European ‘home’ state before they disembarked.

The tensions associated with being both colonized and colonizers are distinctive in the Welsh Patagonian case, and cannot be explained by existing theorizations. For the Welsh in Y Wladfa, their political and cultural colonization was based on domination by a metropolitan state at home, in Wales, rather than in the settler colony. As we will see, these relationships were then replicated in other milieus, including settler USA. Indeed, it was this sense of colonization in Wales that drove the colonizing enterprise. The Welsh of Y Wladfa aimed to create a sovereign space, where they could enjoy political autonomy and cultural dignity in an ‘elsewhere’, even though this was, of course, an indigenous homeland.

Theorizing this scenario requires sustained thought beyond the scope of an article. However, this research does reveal sites of complexity and blind spots in orthodox thinking, which challenge assumptions about the relationship between subject positions as colonized and colonizer. It demonstrates the need to unpack settler subjectivity, not only before they embark but also in the settler location. For, in Y Wladfa, Welsh sovereignty in the settler location was not compromised by a metropolitan regime in Wales or England but by the new Argentine settler government, which had, like the rebels who created the USA, thrown off the shackles of European colonial rule in 1810. Y Wladfa thus highlights that not all settlers have the same relationship to the settler state, complicating understandings about how settler colonialism works, and for whom. Given that Welsh ‘colonization’ lies at the core of their settler subjectivity, then, analysis should begin before Richard Jones Berwyn took his leap into the new Welsh Utopia, back home in Wales.

Welsh as colonized: prejudice and resistance

While recent scholarship on settlers presents a nuanced and perceptive analysis of their experiences in situ, most examinations regard them as a rather homogeneous group, unshaped by their experiences before embarkation. David Preston, for example, provides an insightful exploration of ambiguous indigenous–settler relations during the early contact period in the valley of the St Lawrence, but provides little sense of who the settlers were before they arrived.Footnote 39 However, and especially where migrants were drawn from a distinctive group, we can usefully consider how experiences ‘back home’ shaped the settler colony that was created, melding a migration studies approach with settler studies.

A few scholars have begun this analysis, and Colin Calloway’s work on the eighteenth-century Highland migration, driven by the Clearances, offers a good example. He demonstrates how both Highland and indigenous communities (such as Cree, Mohawk, and Cherokee) were framed as tribal peoples, and branded as racially barbaric.Footnote 40 By shifting the intellectual focus to the period before settling, he reveals the roots of complex affinities and tensions that were experienced in the settler regime. While there are important differences between the Highland and Welsh cases, not least the contrast in motives between the ‘dread of want’ in the HighlandsFootnote 41 and the political purpose of Y Wladfa, both groups were disparaged for their barbarity and failure to grasp modernity. The Welsh and Highland experiences are also analogous to the better-known Irish case, where political subjugation was reinforced by cultural and linguistic suppression.Footnote 42

There is some controversy over whether Wales can be categorized as a postcolonial, or even colonial, society, but what matters here is that the leaders of Y Wladfa understood Wales’ subordination to be colonial.Footnote 43 It is in this sense that we might portray Y Wladfa as an anti-colonial movement, and the Welsh as being colonized. The logics of barbarism and civilization were expressed especially through language policy, which was a key tool of nation-building and political assimilation in modern British history. The imposition of English as the language of public life was enshrined in the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535 and 1542, which made English the voice of government and the legal regime.Footnote 44 The English language thus became a marker of power and authority, which made English literacy both desirable and necessary for the ambitious who aimed to prosper within Britain and its empire.Footnote 45

The Welsh language, in contrast, was regarded as a mark of inferiority and barbarity, which was, at best, associated with a quaint exoticism.Footnote 46 The movement to restore the culture was led by Iolo Morgannwg, who re-established the eisteddfod tradition, and Augusta Hall, who famously invented and promoted the ‘Welsh lady’ costume in a contrived celebration of peasant homeliness and womanly virtue.Footnote 47 However, despite positive celebrations of ‘Welshness’, such images caricatured, homogenized, and restricted Welsh identity, and it remained clear that Welsh was not supposed to be a language of politics, commerce, law, or science.

The most explicit and public expression of such sentiments was aired in the Reports of the Commissioners of Enquiry into the State of Education in Wales published in 1847.Footnote 48 Three English, Anglican, middle-class, and male commissioners travelled around Wales, collecting data and observations on primary schools, and drawing conclusions of unsugared frankness. They blamed poor conditions not on the state or local landlords but on the Welsh themselves. They particularly focused on three prominent and prized elements of Welsh culture: the language, religious nonconformity, and moral standing. While the reports are littered throughout with disparaging remarks, the most quoted passage demonstrates the entwining of language, morality, and poverty: ‘The Welsh language is a vast drawback to Wales, and a manifold barrier to the moral progress and commercial prosperity of its people. It is not easy to over-estimate its evil effects.’Footnote 49 This assault on a Wales that was prized by its public intellectuals and religious leaders for its morality was felt as an insult, a slur, and an open attack on the Welsh way of life.Footnote 50

Like Ireland, Wales was the subject of colonial discourses, which echo those in the wider empire. In her work on the nineteenth-century Welsh novel written in English, Kirsti Bohata demonstrates that linguistic otherness was associated with racialized metaphors of ‘darkness’,Footnote 51 a trope also vivid in the reports. For Commissioner Symons, for example: ‘Superstition prevails. Belief in charms … even witchcraft, sturdily survive all the civilization and light … little or none of such light has as yet penetrated the dense darkness which, harboured by their language … enshrouds the minds of the people.’Footnote 52

Colonialism was, however, more than an undercurrent of everyday disparagement. It was explicitly denounced by the key author of Y Wladfa, the Revd Michael D. Jones. A prolific writer, Jones berated the ancient warlike empires of Egypt, Babylon, and Rome as well as the modern imperialism of Spain, Russia, Turkey, and ‘England’. The latter he condemned for ‘the slaughter of thousands of people in India, Africa, Afghanistan, and just because they were defending their own countries’.Footnote 53 As R. Tudur Jones explains, he identified commonalities between Welsh and other colonial experiences, including the psychological distortion that, according to Michael D. Jones, affects ‘an enslaved nation … which deteriorates to such a point that it wants to destroy its own inheritance, national language and customs’.Footnote 54

R. Tudur Jones adds that, from the viewpoint of Michael D. Jones, ‘one intention of imperialism was to disenfranchise the language, and that this was a step towards extinguishing the [Welsh] nation. The fate of the language was thus a political matter.’Footnote 55 For Michael D. Jones, the struggle against such deterioration required anti-colonial social action, which politicized the language. It was not a question of ‘preserving’ Welsh, which was spoken by around two thirds of people in Wales at mid century, but rather of empowering it. Ironically, it was his global perspective on empire that made him choose settler colonialism in Welsh Patagonia as his key anti-colonial strategy.

For the leaders and ideologues of Y Wladfa, this enterprise sought to make real a utopian dream, to create what Germans called Heimat, an idealized homeland.Footnote 56 While not all the settlers were driven by such high ideals, the importance of Y Wladfa lies not so much in its reality as in what it represented: the promise of national salvation. Moreover, this dream of a ‘new Wales’ emerged not just from disparagement at home but also from the failure of settler colonialism elsewhere to fulfil its promise of dignity and opportunity. The desire for a Welsh national Heimat was an issue of global reach.

Indeed, the inspiration for the Patagonian enterprise emerged from bitter disappointment with settler life in the USA. As a young radical, Michael D. Jones had believed that settler colonization was the answer to the oppressions endured by tenant farmers and those who laboured in the mines, quarries, and iron works. He travelled from Bala to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1848, to assess migrant life, but found that the Welsh were being systematically disadvantaged.Footnote 57 He observed that:

It is a wrench for both the English and the Welsh to leave the places where they were born but when the Englishman lands in any British settlement he will be greeted in his own language …. The feeling of the Welsh settler is very different …; he is greeted in a foreign language and … he must spend a good deal of time catching up with the Englishman.Footnote 58

Thus, language habits in the USA mirrored those in Wales: public discourse and commercial life was conducted in the lingua franca (English), while Welsh was spoken only at home and in chapel.Footnote 59

Just as serious was the loss of ‘Welsh values’, which was linked, in Michael D. Jones’s mind, to the erosion of the Welsh language. Thus, he complained: ‘How can we get rid of the respectable “dam[n]” that the Welshman has learned from the English? How can he learn to be sober like before and to resist prostitution? How can he be made honest like his forefathers and to resist learning “Yankee tricks”?’Footnote 60 The answer, as the historian Alun Davies notes, was ‘“Gwladychfa Gymreig” [Welsh Settlement], a place where the Welsh could be on their own, where they could keep their language, their beliefs and their customs’.Footnote 61 Thus colonization as a nation was the answer, in order to preserve the tripartite foundation of ‘true’ Welsh virtue: language, culture, and Nonconformist religion.

While travelling in the USA, Michael D. Jones encountered the movement to create a separate, Welsh-only colony, which was driven by the energy and charisma of the American-born Edwyn Roberts. Thus, it was in the USA, not in Wales, that the idea of a Welsh-only colony first emerged, from 1857 onwards. Roberts argued, based on his own experience of piecemeal migration to the USA, that the Welsh ‘are leaving the old country in their thousands and if there were a plan that all the Welsh would go to the same place, they would be powerful and effective; but that is not what has happened’.Footnote 62 His campaign was promoted in fervent meetings where nationalist sentiment was stirred through prayers, hymns, and tremendous speeches.Footnote 63 While opinion was very divided over the idea of Y Wladfa in the USA, lively debate in newspapers like Y Drych (The Mirror) generated debate about Welsh identity and the future of the nation, not only in the USA but also back in Wales. Indeed, in a twist to our expectation that colonizing movements begin ‘at home’, it was actually Roberts who addressed the Welsh people via newspaper letters, exhorting them to join his movement to take settlers from the USA to settle in Patagonia. This occurred even before the initiative had got off the ground in Wales itself.

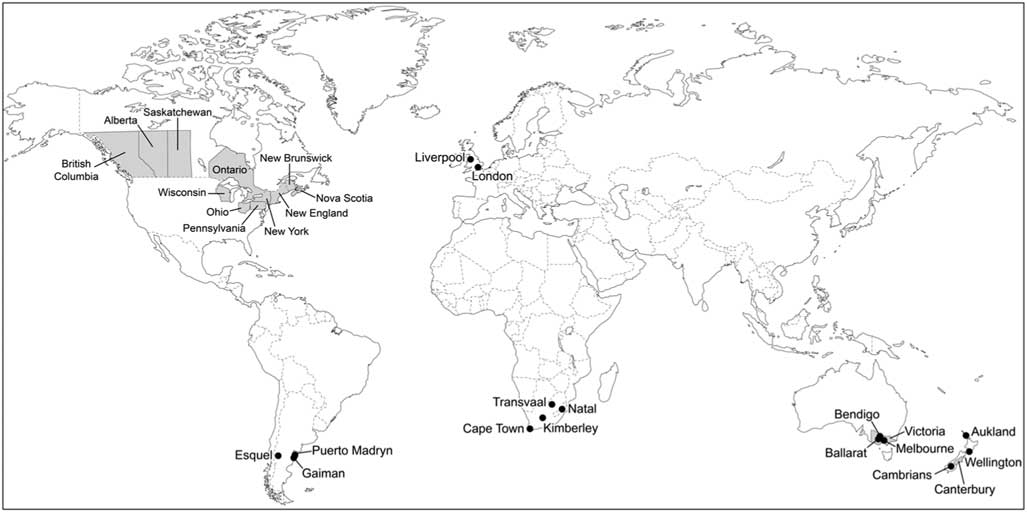

In the end, it was not until 1874 that a sizeable group of migrants actually took ship from the USA to Patagonia aboard the Electric Spark.Footnote 64 The tardiness of this departure from the USA might be explained by Roberts’ decision to travel to Wales in 1860, in order to raise enthusiasm for Y Wladfa in the Old Country. He joined Michael D. Jones’s campaign, which journeyed across the length and breadth of Wales, as well as to London and Liverpool, speaking in ‘hundreds of places’ during 1861 and 1862.Footnote 65 The two men spoke from two different experiences of Welsh subordination, one at home, and the other in the English colony, and they gathered enough supporters to put together the first contingent in 1865. Y Wladfa was not shaped by linear push and pull factors between home and colony, then, nor by a one-directional journey from metropole to colony, but rather by a series of interconnected initiatives and dynamics, which spanned the globe (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Principal locations of Welsh migration. © Antony Smith, Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University.

Nor was this just a three-way story, as other countries, such as Australia, were influential players in this global network, and the topic of Y Wladfa became a conduit for nationalist thinking and action in locations around the globe. In Ballarat, Melbourne, and Victoria, discussions about Y Wladfa, including about the foolishness of the enterprise, took place in two monthly newspapers, Yr Australydd (The Australian, 1866–72) and Yr Ymwelydd (The Visitor, 1874–76).Footnote 66 Bill Jones’s detailed analysis of these newspapers reveals that, as in the USA, Welsh Australians complained about the threat of moral and cultural corruption posed by a multicultural settler society in the coal fields and gold mines. One correspondent, whom Jones cites, decried: ‘The screeching Irish, fawning French … the German, with his hurdy gurdy … and the Scotsman with his “wi drop o gin” … and in the middle is the Welshman, who according to his country is trying to read, sing, pray etc [but] before long will take relish in worse things like his neighbours.’Footnote 67 In what was a common theme, the Australian Welsh linked morality, culture, and a sense of powerlessness to the loss of the Welsh language in a melting pot where English was the lingua franca. For some, the answer was the ‘nationalist’ settlement in Patagonia, prompting campaigns to take settlers from Australia direct to Argentina. Proponents even argued that it was a patriotic duty to increase the numbers in Y Wladfa, and to share their hard-won experience of colonization, in order to ensure success.Footnote 68 Although mass migration from Australia did not take place in the end, Bill Jones demonstrates that, as in the USA, Y Wladfa was a vivid and important beacon of Welsh identity, even for settlers on the other side of the world.

The increase in the academic study of Wales and empire has led Aled Jones and Bill Jones to suggest the calling into being of a ‘Welsh world’.Footnote 69 While more research is needed, Y Wladfa suggests that this Welsh world did more than transpose ‘home’ Welsh culture to other settings, but operated rather as a dynamic network. The reproduction of articles and informative letters from home were the stock-in-trade of Welsh-language newspapers. Thus, Australian newspapers such as Yr Australydd published letters from Wales, Welsh Patagonia, and the Welsh in the USA, republishing excerpts from newspaper reports in Wales (Cardiff Times), England (Liverpool Mercury), and the USA (Baner America (American Flag)), among many others. As Bill Jones observes, this reflects ‘the inter-nationalism of the Welsh press at work’,Footnote 70 demonstrating that newspapers could act as ‘structuring institutions’ not only for groups within countries, as Jones and Jones argue, but also for nations on a global scale through a diaspora press.Footnote 71

The network of common texts and discourses which sustained the global network was made possible by the exclusivity and cultural specificity of the Welsh language, creating intensely local, yet effortlessly global, connections which linked a relatively small group of people, clustered in linguistic pockets around the world. All were experiencing simultaneously a sense of ‘otherness’ in an English-dominated world, and a sense of community within the Welsh world. Here, people – at least those corresponding through newspapers and letters – shared Nonconformist values, cultural habits, and a sense of oppressed national pride. The pivot point for these spiritual, cultural, and political concerns was the Welsh language, which acted as both medium of expression and boundary marker. Y Wladfa was therefore of concern to Welsh speakers far beyond Wales and the Chubut Valley, whether they favoured the settlement or not. For proponents, it was an idealized site where nationalist strands (religious, political, cultural, linguistic) coalesced and where subordination could be overthrown, in contrast to other colonies in the British World.

It is not possible to make sense of Welsh Patagonia, then, without taking seriously the sociopolitical context that shaped settler subject positions, including their sense of political subordination framed in terms of ‘colonization’. This suggests that factors such as political attitudes, pride, identity, and culture could be important in motivating migration, alongside poverty and the lure of opportunity. Fresh dynamics within settler colonialism are revealed by shifting the emphasis to people, rather than state policy, and by focusing on migrants from the margins of the sending society. A global perspective reveals, moreover, that settler colonies do not necessarily follow a linear trajectory, but are shaped by a constellation of interconnected influences and experiences, both ‘home’ and ‘away’. The task now is to examine how this subordinated, ‘colonized’ subject position of the Welsh shaped settler society, and it is to the setting in Patagonia that we turn.

The Welsh as colonizers: ambiguity and conformity

It is not surprising that the Welsh chose the settler colonial strategy to pursue their aims, given the massive expansion of the mid-nineteenth-century global economy from Anglophone locations.Footnote 72 Unlike the USA or Australia, Argentina did not receive large numbers of British migrants. Argentines were connected through informal empire: British companies financed the railway system, telegraph, and post office; British shipping and port services shaped the vast and highly lucrative beef industry; and British banks and financial services underpinned the rapidly expanding economy.Footnote 73 While Argentina became a vital node of Belich’s ‘Anglo-World’ in economic terms, it remained on the margins in geopolitical and geo-cultural terms. Argentina was caught up in global hierarchies too.

Alongside commercial success, then, Argentine elites sought to generate geopolitical capital by promoting the uncritical celebration of Eurocentric ideals, in an attempt to grasp, though never quite to achieve, the prize of ‘First World’ status, as Ricardo Salvatore suggests.Footnote 74 The vision espoused by Argentine elites required what Wolfe would have called the ‘elimination of the native’. This strategy was pursued in a physical sense by the Conquest of the Desert, an army-led campaign of indigenous killing, displacement, and containment, which reached Patagonia in the 1880s.Footnote 75 Alongside this was a population strategy. The racial inflections of white immigration and nation-building were made clear by the Argentine national idealist Juan Alberdi. He argued that ‘to govern is to populate’, and ‘to populate is to educate, to improve, civilize, enrich and to become greater spontaneously and rapidly’.Footnote 76 The geopolitical dimension of this ‘population’ was central: ‘to educate our America in freedom and industry it is necessary to populate it with people from Europe who are more advanced in liberty and industry, as occurred in the USA’.Footnote 77 For this settler state, nation-building was not just about imposing state sovereignty over ‘savages’, but also involved a transformation of global status by bodily importing European-ness in the form of immigrants, and in mimicry of the USA.

The Argentine government pursued this cultural elevation by advertising for ‘ideal’ settlers in the British press, and was pleased to accommodate overtures from Welsh volunteers, who seemed to embody the virtues of industry, high moral standing, and ‘whiteness’. More pragmatically, settlement was also a strategy of control, and Y Wladfa was the state’s vanguard in Patagonia. This was why Dr Guillermo Rawson, the Argentine Minister of the Interior, welcomed the approach by the Welsh Colonizing Society, and agreed to allot land in the Chubut Valley. As was usual, the government paid compensation to indigenous leaders, who then agreed to acknowledge Argentine claims to the territory, and to act peaceably.Footnote 78 In turn, the Welsh Colonizing Society, acting independently of the British government, opened their negotiations, as Glyn Williams reveals, with ‘a direct request for permanent possession of land in Patagonia where an independent government would be established’.Footnote 79 While this was not achieved, it is clear that colonization, broadly defined, was their object.

The territory that they were offered had an ambiguous status. In 1865, Argentina was an independent state, having transitioned from formal Spanish colonial rule in 1810, and yet Patagonia was governed by indigenous nations, who in fact controlled a full half of the territory assigned to Argentina on the map.Footnote 80 However, this fluidity allowed a complex social world to flourish, and the region was home to a significant number of nomadic indigenous communities of different ethnicities.Footnote 81 While leaving few marks on the landscape, theirs was a complex, politically astute, culturally rich, and networked society, which was connected strategically to settler outposts to the south (Santa Cruz, Punta Arenas) and north (Carmen de Patagones), especially in matters of trade.Footnote 82

The Welsh did recognize indigenous sovereignty, and more than once referred to these peoples as ‘the rightful owners of this land’.Footnote 83 They considered this moral conundrum early on, even at the planning stage in Wales, but, rather than rejecting colonialism as a strategy, they adopted the principle of fair treatment. Thus, Hugh Hughes ‘Cadfan’, the author of the ‘Handbook of the Welsh Colony’, proposed that ‘We cannot disregard the rights of the Indians of the land but … we should attempt to make friends of them, giving them whatever is honest, whatever is just.’Footnote 84 Colonization was understood to be a legitimate practice, then, so long as indigenous peoples were financially recompensed, violence was avoided, and any trade did not exploit them.

It is also clear that the indigenous peoples understood the Welsh settlement to be a colony too, as a letter from one local leader, Cacique Antonio, reveals. A perspicacious politician, he wrote to the Welsh settlers about nine months after they had arrived, and set out his terms for this colonial, but far from cowed, relationship:

Without having the pleasure of knowing you personally, I know as a fact that you are peopling the Chupat [Chubut] with a people from the other side of the sea. … I am the Cacique of the tribe of Pampa Indians to whom belong the plains of the Chupat. … I know very well that you have negotiated with the Government to colonize the Chupat but you ought also to negotiate with us who are the owners of these lands.Footnote 85

He then went on to detail the goods that he would like to obtain (rice, tobacco, flour, and yerba mate, a form of tea), to be exchanged for the rhea feathers and guanaco skins that he could supply. He stressed the quality required, as well as the need for ready money and Spanish language skills. Cacique Antonio’s letter reveals him to be a businessman who was already enmeshed in global flows of money, goods, and power, through trading with Patagones. He knew that his guanaco skins became carpets and rugs for the upper classes in Buenos Aires, while his feathers topped off hats in London and Paris. These were global connections indeed. For him, colonialism was a de facto reality, and he was concerned not with ‘whether’ settler colonization would take place, but ‘how’, imagining that he could adapt his trading relationships to make it mutually beneficial.Footnote 86

Argentine, Welsh, and indigenous leaders thus all understood Y Wladfa to be a settler colony, but the Welsh ‘colonizers’ were not all-commanding. The first years were characterized by vulnerability and dependency, rather than power. Like many pioneer settlers, their relationship with indigenous inhabitants was vital for the Welsh, and the archives express the ambivalence that their subject position dictated. The first Welsh contingent arrived in the winter of 1865 to dry, windswept plains, which were very different from the verdant hillsides of Wales. The archives tell us that they struggled to milk their rebellious cattle and herd their unfenced sheep.Footnote 87 Their crops failed, pumas prowled, and they always feared that ‘every dust cloud that swept the horizon carried to their alert ears the muffled tramp of an Indian host’.Footnote 88

When ‘the Indians’ did finally arrive, in the diplomatic form of Cacique Francisco and his wife, peaceful and cooperative relations were quickly established.Footnote 89 The writers of the Welsh archive claim that it was their policy of friendship that ‘tamed’ the savage nomads. One of the first colonists, W. Casnodyn Rhys, for example, asserts that: ‘the kind treatment of the Indians by the Welsh settlers gradually disarmed these wild nomadic tribes, and … converted them into warm, even passionate, friends’.Footnote 90 However, it was more likely a case of strategic generosity, as the indigenous groups saw the Welsh settlement as offering a more convenient trading post. Cacique Francisco, in particular, adopted a policy of friendly assistance, probably in order to ensure that the settlement did not fail.Footnote 91 He taught the settlers how to ride and handle horses; he showed them the group hunting techniques at which he excelled, and how to cook and camp, as well as how to navigate the landscape and find water, river crossings, and pathways.Footnote 92 As is often the case, rather than settler bravado, the early settler–‘Indian’ relationship was characterized by Welsh dependency and gratitude.

Cacique Francisco’s shared knowledge helped the Welsh to eat well and thrive in this terrain, which in turn fostered a settler identity embedded in the land. They made it theirs, creating towns, businesses, schools, chapels, and a stock of pioneer stories.Footnote 93 As the Welsh increased in number, adapted, and prospered, they took on a ‘Second World’ identity, following Lawson and Johnston’s definition, which melded aspects of both indigenous and metropolitan authenticity, and created a sense of ownership of the Chubut Valley.

This authority was reinforced by a Welsh capacity to exceed indigenous life-ways, particularly by developing irrigation systems, which allowed them to sow and reap prize-winning wheat, developing prosperous farms and towns.Footnote 94 Their initial vulnerability had shaken the usual racial hierarchies, but this settler success seemingly confirmed the superiority of European civilization, and set the ‘natural order of things’ back on an even keel. This ‘natural’ superiority over the indigenous, redolent with colonialist attitudes, is conveyed, for example, by Jonathan Ceredig Davies’ memoirs, which reflect on Y Wladfa’s early years. He discusses his ‘friendly’ relationship with ‘a chief named Gallech … such a homely and good-natured old man that he was quite a favourite with the Welsh people’. Gallech’s son ‘Kingel … who could speak Welsh well’, when asked to dine, ‘behaved almost like civilized people, using knives, forks, and spoons’.Footnote 95 We might assume, of course, that the indigenous people whom the Welsh met were equally convinced that their way of life was superior, and perhaps hid their own disdain behind polite façades, though little trace of their opinion at the time remains. However, the Welsh sense of ‘European’ superiority, despite being disparaged themselves, was never explicitly questioned, at least in the archives.Footnote 96

It is right that we should be wary of portraying colonization as friendship, then, but at the same time we should not dismiss these relationships – which were sometimes close – as groundless or merely romanticized appropriation. The easy binary of ‘oppressive settler’ and ‘victimized indigenous’ does fit the brutality of the Argentine state policy, which aimed explicitly to ‘eliminate the native’. However, it cannot make sense of the social relationships in Y Wladfa, of indigenous power and Welsh vulnerability, nor can it clarify the subject position, and political affinities, of the Welsh. For this settlement was anchored in the desire for cultural dignity and political sovereignty, and it is evident that the Welsh recognized that these objectives were precious to indigenous populations too.

Matters came to a head with the arrival of the army and the Conquest of the Desert, which, by 1882, brought killings and an internment camp to the Chubut Valley.Footnote 97 The Welsh responded not with relief, satisfaction, or indifference, but rather, and without exception, with horror and repudiation. For example, W. Casnodyn Rhys notes that ‘Those were terrible days for the settlers … for our own sympathies were with the Indians.’Footnote 98 Indeed, the Welsh sent a strongly worded letter ‘signed by all’ to General Vinnter, who led the Conquest of the Desert in Chubut in 1882, in which they ‘plead for your clemency and … express our strong feelings in favour of some of the “aborigines”’, asking him to ‘leave our old indigenous neighbours in their homes’.Footnote 99

A sense of Welsh responses emerges from notes made by Jonathan Ceredig Davies for his memoir. He asserts that ‘my sympathies were on the side of the poor Indians; and I think most of the Welshmen in the colony felt as I did’.Footnote 100 He went on to describe the arrival of a large group of captured indigenous people into the settlement, and expressed a mixture of heartfelt emotions:

I well remember seeing passing me one day some hundreds of these unfortunate prisoners surrounded by soldiers on their march to the sea to be taken away in vessels to Buenos Aires where they were given away as servants to rich people or rather as slaves, practically. I could not help shedding tears to see the poor Indians thus treated for trying to defend their own liberties.Footnote 101

His description of the ‘unfortunate prisoners’ conveys a moment when the uneven yet parallel lives of the Welsh and indigenous are revealed to be a binary split, one which allows Davies, the colonizer, to stay, while forcing ‘the Indians’, the colonized, to go.Footnote 102 This is a brutal example of Wolfe’s indigenous elimination. However, Davies’ experiences of friendship created genuine distress (‘shedding tears’) and feelings of pity (‘poor Indians’) but also anger (‘or rather as slaves, practically’) and perhaps helplessness, given the scale of the exodus and the diminishing political power of the Welsh.

The final phrase, though (‘trying to defend their own liberties’), suggests that this affinity was political, and based on the common desire of both the Welsh and the indigenous communities to enjoy political sovereignty and cultural dignity. By the 1880s, the Welsh no longer depended on indigenous help for survival or livelihood, and social interaction had never been intimate. This suggests that their defence of ‘the Indians’ was not motivated by economic necessity or close ties, but rather by a fellow-feeling of indignation at the loss of political autonomy, and at cultural abjection.

This sense of affinity was probably spurred not only by experiences as ‘colonized’ subjects at home in Wales, but also by their own struggles with the Argentine state. For the Welsh too were disciplined, their autonomy constrained, and their culture demoted by the arrival of the Conquest of the Desert and the state that it represented, echoing the political and cultural suppression that they had experienced back in Britain. Once the army had arrived in the area, President Roca asserted central control, appointing Juan Finoquetto as Commissar in 1881. His task was to put the Welsh settlers in their Argentine place.Footnote 103

Y Wladfa’s charismatic leader, Lewis Jones, had hoped to institutionalize Welsh power by transforming their local government into a formal municipality through government statute.Footnote 104 This would have allowed the Welsh to keep a modicum of local power and political autonomy. However, Finoquetto branded Welsh efforts to achieve municipal status as ‘a mutiny against the national authorities’ in his annual report, under the heading ‘criminality’.Footnote 105 Lewis Jones and Richard Jones Berwyn could do little but submit to the dominant regime in Buenos Aires, despite complaining of the ‘many informal indignities heaped upon us’, the ‘caprice of a young official’, and attempts to ‘impeach our political rectitude’ in a letter to the President of the Republic.Footnote 106 The terrain of this battle was political sovereignty, a core aspiration for the Welsh nationalists in Wales and around the world.

To the loss of power was added disparagement and the marginalization of Welsh culture. Around the same time, Finoquetto tackled the question of schooling, an issue that inevitably struck at the second foundation of Y Wladfa, the Welsh language. Finoquetto imposed the Argentine state schooling system on the Welsh, which implied learning in Spanish and about Argentine history.Footnote 107 This issue married political dispossession to cultural disdain and enforced linguistic assimilation, issues that were again very familiar in nineteenth-century Wales.

The flashpoint came when a literacy census was published in the newspaper La Nación on 15 October 1882, which reported that 200 of the 700 children in the colony were deemed illiterate, according to figures compiled by Commissar Finoquetto.Footnote 108 This result was hotly contested by the community leaders Jones and Berwyn, who saw this as a way to cast aspersions on the Welsh intellect and Welsh-language schooling. They accused Finoquetto of deliberately providing misleading information, and began an open, bitter battle. ‘It is clear now’, notes Jones in his journal, ‘that the figures included all the children, one day old and upwards!’Footnote 109 Jones and Berwyn refused to collect and supply accurate data, and Jones’s notebooks record acrimonious conversations on the streets of Trelew, and refutations in the newspaper columns of La Nación. Finoquetto complained that the Welsh refused to send their children to the new state school, but Jones and Berwyn countered that ‘the settlers don’t send their children to this school because the teacher doesn’t speak the language that the children have known up till now’, and added that people ‘consider the statistics are only motivated by a desire to devalue them in the public eye’.Footnote 110 The sensations expressed here – indignation, injustice, wounded pride, and powerlessness – were echoes of feelings expressed in Wales.

These indignities were crowned when, in the end, Finoquetto arrested both Jones and Berwyn, imprisoned them in a show of force, and sent them to Buenos Aires for trial.Footnote 111 Although they were quickly released, this demonstrable capacity of the settler state to discipline even the strongest Welsh colonists confirmed the end of Welsh political autonomy, cementing the subordination of both the colony and the Welsh language to a position very similar to that in Wales. In the same year (1883), Finoquetto labelled Welsh as a ‘dead language’ of schooling, and asserted the superiority of Spanish instruction in the new national schools.Footnote 112 The installation of Governor Luis Fontana in 1884 simply confirmed Welsh political and cultural subordination to the state. Citizenship thus stripped them of political power and obliged them to assimilate, confining the Welsh language, as in Wales and the diaspora, to the home and the chapel. The central goals of Michael D. Jones, Abraham Matthews, Edwyn Roberts, Lewis Jones, Richard Jones Berwyn, and many others were crushed by inclusion in this new nation-state, mirroring mechanisms of subordination back home. The Welsh were caught in linguistic power plays that had global reach.

Conclusion

The Welsh occupied a complex subject position in the Patagonian context. On the one hand, they were clearly colonizers. They, the Argentine state, and indigenous peoples all understood this to be the case. The Welsh did not question their ‘natural’ superiority over the ‘primitive races’ and, while they recognized the indigenous inhabitants as the ‘rightful owners of this land’, they justified the colonial enterprise by adopting strategies of fair trading and non-violence. Their ideas about racial hierarchies naturally reflected the dominant norms of nineteenth-century thinking. And yet, on the other hand, their subordinate status within the British World, and the relationships of dependency and camaraderie that they developed with the indigenous people, made them recognize ‘the Indians’ as social agents, and perhaps even as friends. More than that, the concern with indigenous ‘liberty’ indicated a sense of not just emotional but also political affinity with the indigenous cause, and they certainly were swift and clear in their condemnation of the Conquest of the Desert. This affinity was perhaps inspired not just by the cultural depreciation and political subordination that they endured at home, but by the erosion of their political autonomy in Patagonia, which occurred in parallel with the Conquest of the Desert.

The ambiguity of the Welsh situation as both colonizer and colonized linked not only to their experiences in Britain and the British World, but also to their treatment by the Argentine state. Their desire for political autonomy and the enjoyment of cultural difference was quashed by a settler state that demanded subordination and conformity as the price of citizenship. This suggests that settler colonial theory should look more intently within the colonizer/colonized binary, and pay close attention to differentiations within the ‘settler’ category. Moreover, it suggests that theorists should recognize that settler states themselves existed within a global hierarchy, and were anxious to achieve an elevated global status. Looking at countries peripheral to the dominant Anglophone examples starkly reveals the dynamics of domination, aspiration, and subordination which played into geopolitical hierarchies, and in turn shaped settler policy. In Patagonia, Welsh independence in the colony was not suppressed by a metropolitan state, as Lawson and Johnstone assumed, but by the settler colonial state, which targeted precisely those elements – the Welsh language and political autonomy – that were undermined in Wales and that were the chief components of Y Wladfa as an ideal.

The Welsh Patagonian case allows us to think about settler colonialism from a peripheral position in global politics. The ‘colonized’ subject position of the Welsh, which travelled with them around the world, invites us to unpack ‘the settler’ as an analytical category, a move which reveals assumptions within conventional approaches, opening spaces which confuse, but also enrich, our understandings.

First, settler colonial theory imagines the settler to occupy a position of power within a binary relationship between the colonizer and the colonized, but this research reveals the presence of many ambiguities. It was resistance to Welsh ‘colonization’ at home, echoed in settler relations in the wider British World, which motivated the settlement in Patagonia. Here, far from dominating indigenous inhabitants, the Welsh depended on them, respected their autonomy, and eventually tried to defend them against the Argentine state, which in turn disciplined and suppressed their own struggle for political and cultural autonomy. Clearly, Welsh whiteness and European-ness endowed them with privileges in global hierarchies and in the Argentine nation-state, whereas indigenous communities suffered the violence and indignity of ‘elimination’. However, this colonizer–colonized bifurcation masked complex social relations in the colony. The case study suggests the possible importance of common goals and political affinities between settler and indigenous populations, as well as practices of domination and discipline within the settler state, opening this space as a political and politicized arena. Rather than suggesting that the Welsh occupied separate subject positions in separate locations (as colonized in Wales and colonizer in Argentina), the analysis suggests that they occupied both simultaneously. They were colonizing from a colonized position, which inevitably shaped the nature of their settlement and its social relationships.

Secondly, in order to make sense of this ambiguous subject position, a method was adopted which foregrounded settler motivations, and therefore the social and political context that shaped the enterprise. This entailed embracing a migration studies approach that interrogated the back story of migrants, but also adopting a global perspective, which placed Y Wladfa within the whirlwind of human movement around the globe. Taking this holistic view of the Welsh Patagonian settlers revealed that they were constituted by not two (colonizer–colonized) or even three (indigenous–settler–metropole) but at least five dimensions: relations between England and Wales in Britain; ongoing connections between Welsh Patagonia and Wales; relations between Y Wladfa and the Argentine state; Welsh Patagonian and indigenous Patagonian relationships; and Welsh linkages to settlements in the wider British World. Moreover, it identified the centrality of political, and not just economic, motives, and highlighted the role of ideas about civilization and barbarism. The supremacy of European, and especially Anglophone, ‘civilization’ set the terms of social rankings on the geopolitical ladder, which Argentina sought to climb, and in the cultural realm, which the Welsh of Y Wladfa proudly sought to rebuff. This was set against caricatures of barbarism, which both the Welsh in Wales and the indigenous communities of Patagonia, among many other ‘savage races’, embodied. Taking a 360-degree view not only reveals the way in which such discourses operated at many levels, in multiple sites, and in an intermeshed way, but also highlights the interconnections between points of resistance (Bala, Ohio, Ballarat, Trelew), and suggests that moments of affinity between subjugated Welsh and indigenous Patagonians were possible.

Finally, this research has demonstrated the crucial role that ‘marginal’ examples can play in exposing and challenging the assumptions of theories based on ‘core’ cases. Wales was marginal to a Britain dominated by England, and is the marginal case within the ‘four nations’ approach to the British World, while Argentina played a marginal role in the Anglophone global economy, and itself regarded Patagonia and its people as a barbaric marginal realm, which required forcible inclusion into the nation-state. Starting our thinking from those who are on the receiving end of powerful action also foregrounds their agency, and highlights the practices of domination from a fresh angle, one that builds in resistance. This strategy has important theoretical implications.

The Welsh Patagonian initiative reveals the central importance of power relations ‘back home’ in shaping dynamics between the ‘four nations’ of the British World, and their actions in the colonial setting. For Michael D. Jones and his colleagues, the sense of Welsh subordination, and its realities, was pivotal to generating Y Wladfa. We might ask more broadly, then: how do such hierarchies shape ‘national’ responses in colonial administration, the military, or the formation of settler colonial societies? Moreover, researchers might usefully consider examining the British World not just from its ‘core’ locations but also from more marginal sites of empire, including informal empire, where Britishness was thinner, more strained, and contested.

Settler colonial theory provides an important political and ethical position from which to approach a case such as Y Wladfa, as it exposes the fundamental injustices endured by colonized peoples under settler governments. However, the Patagonian case reveals Welsh–indigenous relations as complex, rather than binary. Indigenous agents enjoyed considerable economic and political power, and some settlers were at odds with the settler state. Acknowledging that the settler can be both colonizing and colonized, and tracing this ambiguity back to their subject position at home, challenges settler colonial theory to make sense of such complexity, while at the same time not diluting the fundamental facts faced by colonized peoples: dispossession, disempowerment, assimilation, and the ever-present threat of violence. Recognizing that ambiguity and affinity are also part of this story is important. On the one hand, it suggests spaces where cross-community solidarity might be developed, while, on the other, it invites us to consider whether ‘friendship’ is an unwitting technique of colonization too.Footnote 113 Indeed, this issue is far more than a theoretical puzzle or a historical curiosity. The stakes are much higher: even today indigenous communities in the Chubut Valley are facing struggles over land rights, assaults on their dignity, and brutal violence.Footnote 114 For them, settler colonialism is not a thing of the past, even in Y Wladfa.

Lucy Taylor is a senior lecturer of Latin American studies in the Department of International Politics, Aberystwyth University. She is fluent in Welsh, Spanish, and English.