Introduction

Global exchanges in higher education have been a key mechanism for the circulation of persons and ideas. Although transnational educational networks have existed for centuries, the history of institutionalized scholarship programmes, as specific instruments of interregional exchanges, is fairly short. The international scholarship architecture evolved approximately a century ago and entered its ‘golden age’ during the Cold War, with the emergence of ‘the large-scale American and Soviet programs used to promote their socioeconomic and political models across the globe’.Footnote 1

Among the chief beneficiaries of this ‘golden age’ were students from colonized and formerly colonized territories, many of whom came from Africa. While most African students had formerly gone to study in the colonial metropole up to the 1950s, they would increasingly attend universities outside the metropole and its imperial realm from the 1950s onwards. Within a few years, African students were ‘seeking the golden fleece in almost every corner of the civilized world’, as a Ghanaian newspaper put it in 1963.Footnote 2 First dozens, then hundreds, and eventually tens of thousands of African students entered seminar rooms and lecture halls in the United States and the Soviet Union, in West and East Germany, in Yugoslavia and Scandinavian countries, in China, and in the rest of the socialist camp. Countries such as India, Ghana, Egypt, and Ethiopia also turned into both important host and sending states in these circulations.Footnote 3

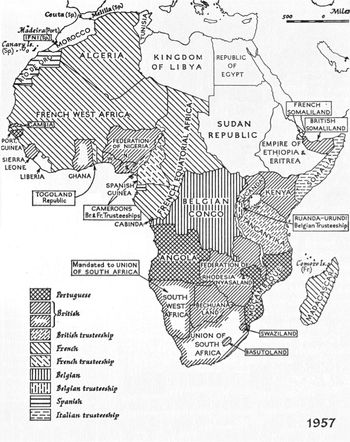

Tanganyika, one of the territories in which the British had invested very little in terms of education prior to independence, illustrates how the number of destinations multiplied during the ‘golden age’ of scholarships. By 1960, according to official information, Tanganyikans attended institutions of higher learning in fourteen countries, mostly in western Europe, North America, Asia, and Africa (see Table 1). This was already a significant expansion compared to earlier years. By 1973, this number had grown to more than forty, including several Eastern bloc countries (see Table 2).

Table 1. Tanganyikan students abroad, 1960

Source: The National Archives, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 141/17830, Director of Special Branch to Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Security and Immigration, Dar es Salaam, 16 February 1960.

Table 2. Tanzanian students at overseas universities on degree and non-degree courses, 1973–74. The list is incomplete as it only covers Tanzanians on official scholarships and does not include major destinations such as the United States, the United Kingdom. and the Soviet Union

Source: United Republic of Tanzania, ‘Annual manpower report to the President, 1974’, Dar es Salaam, 1975, p. 47.

Historians have explained this diversification of destinations and the increasing numbers of students from Asia, Africa, and Latin America at overseas universities first and foremost as the result of three interrelated processes: Cold War rivalries, policy responses to decolonization, and the rise of educational planning as an instrument of modernization and development in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 4 Following the Bandung conference in 1955, superpowers as well as smaller states discovered the education of inceptive ‘Third World elites’ as a major field of Cold War cultural diplomacy. In the late 1950s, the USSR, under Khrushchev’s destalinization drive, and its allies from East Berlin to Beijing launched a charm offensive to knit new ties with anti-colonial movements and newly independent states.Footnote 5 Western states without colonial possessions followed suit and joined the Cold War scramble for incumbent elites, while colonial powers drastically stepped up scholarship programmes that were already in place. By the 1960s, educational programmes had become an international standard. They ‘received funding from the major international development agencies and were translated into the development plans of the newly decolonized countries’.Footnote 6

This article reconsiders the years leading up to this ‘golden age’ and the emergence of new mobilities by expanding the focus from states and officially planned and funded scholarship programmes to a broader view, which includes the role of African students, mediators, and supporters, as well as transnational networks of non-state actors. While referring to examples from several regions, the article particularly deals with East African territories under British rule. In comparison to French-ruled territories, and most British-ruled territories in West Africa, possibilities to access higher education were (even more) scarce in East Africa; moreover, there was only one institution offering academic degrees in the whole region.Footnote 7 Given the limited educational opportunities within the region, African youths and politicians forged new routes to universities and other educational institutions in countries other than the colonial metropole. This transition, from a limited number of imperial destinations to a broader global variety of destinations, cannot fully be explained by policy changes and Cold War scrambles over postcolonial proto-elites. A broader set of actors, African actors in particular, had an impact on how educational mobility played out in relation to larger processes. Non-state initiatives and networks were crucial in broadening the ‘repertoire of migration’, that is, the range of the destinations, practices, and customs of mobility, which were of course shaped by the political, economic, and legal regimes in place.Footnote 8

Arguing that it is necessary to acknowledge the initiative of students and various non-state actors in extending the repertoire of educational migration, this article discusses three different types of educational mobility that emerged between 1957 and 1965, detailing the role of non-state actors; official responses to unregulated mobilities; the influence, and use of, Cold War rivalries and rhetoric; and the impact of these mobilities. The first of the three routes under consideration here is the ‘Nile route’. Young men from various East African countries passed through Uganda and Sudan to Egypt, and proceeded, at times, to eastern Europe. Mobility along this route unsettled colonial authorities, but kept increasing owing to the presence of African intermediaries, anti-colonial networks, and supporting individuals along the way. The emergence of the second route, the airlifts of more than 800 students from East Africa to North America between 1959 and 1961, shows the importance of transnational non-state networks, and the relevance of economic support from a variety of African actors to realize the journeys. The third type of educational mobility was the departure of hundreds of African students from the Eastern bloc in the early 1960s, who crossed the Iron Curtain seeking new or better educational opportunities in Western countries. Against Western efforts to frame this as an ‘exodus’, in terms of an inherent defect of communism, the educational migrants exploited the opportunities that the Iron Curtain offered, but refused to be instrumentalized for Cold War propaganda.

Such ‘African uses of the Cold War’ have been foregrounded in recent analyses of anti-colonial liberation struggles, showing how colonial oppression and white minority rule led Africans to establish ‘inevitable pipelines into exile’ and ‘roads to freedom’ to neighbouring countries.Footnote 9 This approach is extended here to routes towards higher education beyond the continent. Based on published memoirs and oral history interviews, materials from European and African archives, and secondary literature and unpublished dissertations, the article details how Africans established routes that cut across territorial boundaries, imperial spaces, and the Iron Curtain, how they used windows of migration opportunities, and how they propelled state authorities to react.

As recent accounts have shown, looking at the transnational history of educational mobilities and scholarship programmes through a combination of top-down and bottom-up perspectives brings out the unexpected dynamics, experiences, and contradictions that are missed otherwise.Footnote 10 Officials reacted with attempts to control novel movements and flows, which then reflected back on mobilities.Footnote 11 The article thus traces the dialectic relationship between non-state initiatives to bring about new mobilities, on the one hand, and official understandings of, and reactions to, these emerging routes, on the other. Showing these interrelations enables an epistemological break with the often hagiographic and Western-centric approach to the ‘successes’ or ‘failures’ of scholarship programmes, which are only of limited use for the global history of higher education.Footnote 12 Additionally, a focus on the mobilities of actors helps to integrate ‘different analytical perspectives and spatial scales’, a task that is ‘especially acute in the history of education and educational exchange’, as Heather Ellis and Simone M. Müller have recently argued in this journal.Footnote 13

In the context of this article, this approach serves to trace mobilities and elucidate differing motives between (prospective) students, on the one hand, and mediators and state actors, on the other. This relation was often strained, as students did not necessarily share the ideological and political aims associated with the provision of bursaries and other assistance. Following a sketch of the broadening repertoire of educational migration in British-ruled territories of East Africa in the 1950s, the article discusses the three different routes to education in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Broadening the repertoire of educational migration

The diversification of transnational routes to higher education from East Africa during the 1950s was rooted in an unprecedented discrepancy between aspirations and opportunities. Increased, albeit still limited, investment in secondary education produced a new group of Africans, whose career aspirations were frequently frustrated. Taking the example of Kenya in 1952, Africans, who constituted 96% of the population and contributed most of the state’s revenue through taxes, received 11.3% of all government bursaries for higher education, with the remainder going to Asians and Europeans, who made up only 4% of the territory’s population.Footnote 14 Young educated Africans’ demand for higher education vastly outmatched what the colonial system had to offer. The official options that were available to those with excellent performances (and willingness to abstain from open anti-colonial activity) were Makerere College in Uganda, and scholarships for overseas studies, usually in the UK. Access to these scholarships reflected inequalities along racial, regional, and ethnic lines. While many Baganda attained the necessary credentials, and also acquired scholarships for the United States and India, students from other regions in Uganda remained largely excluded from these opportunities. Consequently, groups other than Baganda, particularly from the northern parts of the country, were more likely to travel along the ‘Nile route’ and seek education in the Eastern bloc or elsewhere.Footnote 15

Aspirations to attend higher education institutions reflected both the fact that social mobility was tied to the symbolic capital of university degrees, and new dynamics of decolonization. Speaking about those whose academic credentials were insufficient to open the gates to university, the Kenyan historian and US airlift beneficiary Mutu Gethoi remembered that ‘those of us next in the ranks were finished. You became a teacher or policeman, or you were employed by the railways or post office.’Footnote 16 Such limited prospects were unsatisfying to many. Students of a technical institute in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, sent a letter of resignation to the territory’s Public Works Department, explaining that they refused ‘to be trained in such a way that we only provide cheap labour to the Engineers’, all of whom were non-Africans at the time.Footnote 17

University degrees, in turn, held the promise of advancement and the speedy replacement of even top-level European officials by Africans. As one Zanzibari put it in a scholarship request to the trade union federation of East Germany, the need for people ‘capable of taking responsible posts is extremely earnest if expatriate colonial staff are to be done away with and sons of the soil to take over their place’.Footnote 18 Approaching independence after more than seven decades of foreign rule, there was not a single engineer of African descent with a university degree in Kenya, and only one in Tanganyika.Footnote 19 Education had turned into a matter of decolonization, and vice versa, and also because students held to be politically subversive were expelled from public or mission schools, and were forced to find alternative pathways of education.Footnote 20

These alternatives were funded through private and official, and internal and external sources. Within the territories, ethnic-based self-help associations and farmer cooperatives financed overseas scholarships for promising community members. Beyond East Africa, other postcolonial countries, as well as educational institutions, provided additional opportunities. As early as the 1940s, small numbers of East Africans went to study at historically black colleges in South Africa, the United States, and Canada.Footnote 21 Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser began taking in students from East Africa in the early 1950s (discussed in more detail below).

Studying in South Asia became more common during these years. Some East African secondary school leavers, including colonial subjects of Asian origin, went to South Asia for higher education with the support of Indian government scholarships, under the auspices of Jawaharlal Nehru’s anti-colonial drive. Initiated to improve India’s image through Afro-Asian solidarity put into practice, this cultural diplomacy pet project of Nehru began with around 200 students from the entire African continent in 1955; by 1965, around 600 Africans studied at Indian institutions with government fellowships.Footnote 22 Apart from benefiting from these government scholarships, other East Africans came to India or Pakistan through the private support of wealthy employers of Asian origin, or secured scholarships from welfare-oriented or political associations that were based on religious affiliation and open to Africans, such as the East African Muslim Welfare Society established under the patronage of the Aga Khan, who had many Ismaili followers in East Africa.Footnote 23

New, or expanding, educational migration circuits such as the Egyptian and the Indian Ocean connections fostered political mobilization and the circulation of anti-colonial, Marxist, and pan-African ideas.Footnote 24 Students from East Africa were soon represented in the African Students Association in Bombay, took part in progressive conferences such as the Asian Socialist Conference Meeting in 1956, penned anti-colonial newspaper articles, and aired broadcasts in Kiswahili for East African audiences on Radio Cairo and All India Radio.Footnote 25

Colonial authorities tried to prevent further radicalization of anti-colonial struggles through returnees. Immigration authorities searched the luggage of returning students and activists and confiscated any literature considered subversive.Footnote 26 Colonial anxieties were aggravated by the awareness of travel to communist states in the late 1950s. Although colonial governments in East Africa tried to prevent Africans from leaving the continent and going to the Eastern bloc, dozens had already taken up studies or vocational training behind the Iron Curtain before Tanganyika (1961), Uganda (1962), Kenya (1963), or Zanzibar (1963) had become independent. While there were only two Zanzibaris studying in socialist countries in 1958, more than one hundred attended universities behind the Iron Curtain in 1962.Footnote 27 As colonial authorities (and several postcolonial governments) not only discouraged but also actively prevented eastbound journeys, for fears of communist subversion and disruption of government interests, the question arises how East Africans made their way to the socialist camp – as well as other new destinations – without official scholarship channels and without the necessary passports.

The ‘Nile route’

British colonial officials were dumbfounded when they discovered what they called the ‘Nile route’, which East Africans used to get from Uganda to Sudan and Cairo, and from there to the Eastern bloc. Illicit Trans-Sahelian passages undermining colonial authority were by no means new. Jonathan Miran has shown how thousands of West African pilgrims heading to Mecca frustrated colonial attempts ‘to channel, regulate, and control … and enforce a regime of mobility along the Sahel and across the Red Sea’.Footnote 28 The ‘Nile route’ from south to north, however, was unprecedented, given its connection of higher education and supposed communist indoctrination.

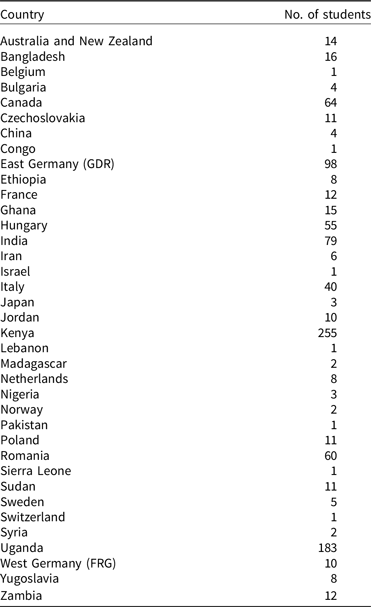

The ‘Nile route’ could only emerge because of political upheavals and the advance of decolonization in North Africa, particularly Sudan’s independence in 1956, and the preceding Egyptian military coup under Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1952 (see figure 1). Following the 1956 Suez Crisis, Cairo quickly morphed into an anti-imperialist hub.Footnote 29 Nasser’s government stepped up its scholarship offers – some two thousand students from sub-Saharan Africa were present by 1964 – and supported anti-colonial parties from sub-Saharan Africa with office spaces, air travel, and government stipends of 100 Egyptian pounds to representatives.Footnote 30 In 1958, a special guesthouse in Cairo was christened ‘The East Africa House’. It accommodated approximately forty students from the region, some of whom became involved in anti-colonial politicking and the forging of educational routes beyond the continent. This usually happened through their activity for the offices established by leaders of anti-colonial nationalist parties in Cairo – including the Uganda Office, the Zanzibar Office, and the Kenya Office.Footnote 31 By 1962, liberation movements and opposition parties from at least fifteen African countries had opened offices in Cairo. They functioned as relay stations for scholarships, providers of trade union courses, and centres of military training, in the case of organizations engaging in strategies of armed struggle.Footnote 32

Figure 1. Alien rule in Africa, 1957. Source: adapted from J. D. Fage, An atlas of African history, London: Edward Arnold, 1975, p. 49.

The Kenya African National Union (KANU) had offices in Uganda, Khartoum, Cairo, and (after 1961) Dar es Salaam, which made scholarships arrangements and facilitated journeys, as did faith-based organizations such as the Kenya African Moslem Political Union.Footnote 33 The Kenya Office in Cairo was established in 1959 by three students, two of whom had acquired an Italian scholarship, but then went up the ‘Nile route’ because colonial authorities had impounded their passports on the planned day of their departure. Like the third co-founder, a Kikuyu student arrested for his supposed involvement in the Mau Mau insurrection, they had escaped illegally, and began studying in Cairo, but gave up their studies to work full time for the nationalist cause.Footnote 34 Students turning into proto-diplomats, or becoming politicized and militarized along the way, were not exceptional: the fluidity of roles and aspirations was a central characteristic of clandestine trajectories such as those along the ‘Nile route’. Education could serve different ends, especially in the case of anti-colonial groups, which came to embrace strategies of armed struggle: students could turn into trained guerrilla fighters and vice versa.Footnote 35

As Ismay Milford has observed, Cairo’s new character as a crossroads of mobility troubled the British because ‘the anticolonial hub that the Colonial Office had grown used to – London – was to some degree protectable, controllable and observable. Cairo was not.’Footnote 36 Since the late 1950s, travellers could contact the embassies of China, the Eastern bloc, and African independent countries to apply for scholarships and visas. As an aspiring Cold War power, China had begun to hand out scholarships in the late 1950s as well. By 1961–62, 118 African students (including 18 Zanzibaris, 4 Ugandans and 2 Kenyans) had arrived in China; in several cases, the arrangements for these trips had probably been made in Cairo.Footnote 37

To a smaller extent, support structures also evolved in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum. While the government only allowed few liberation movements to open offices in the capital, travellers could approach several diplomatic missions of postcolonial and communist countries. The Ghanaian embassy in Khartoum, for instance, handed out financial assistance to young men waiting for a visa that would enable them to enter Egypt.Footnote 38 In a few cases, Eastern bloc diplomatic missions rendered the trips more convenient to selected individuals and arranged airlifts straight from Khartoum. According to British intelligence, the Ugandan Charles Nyeko had ‘stayed six weeks in Khartoum and was very well looked after by the Czech Ambassador. He left Khartoum for Cairo on the 31.10.1960 by a Comet Jet airline and stayed in the Continental Hotel in Cairo for one night. He flew to Prague on 1.11.1960. On arrival in Prague he was given Shs. 800/- pocket money.’Footnote 39

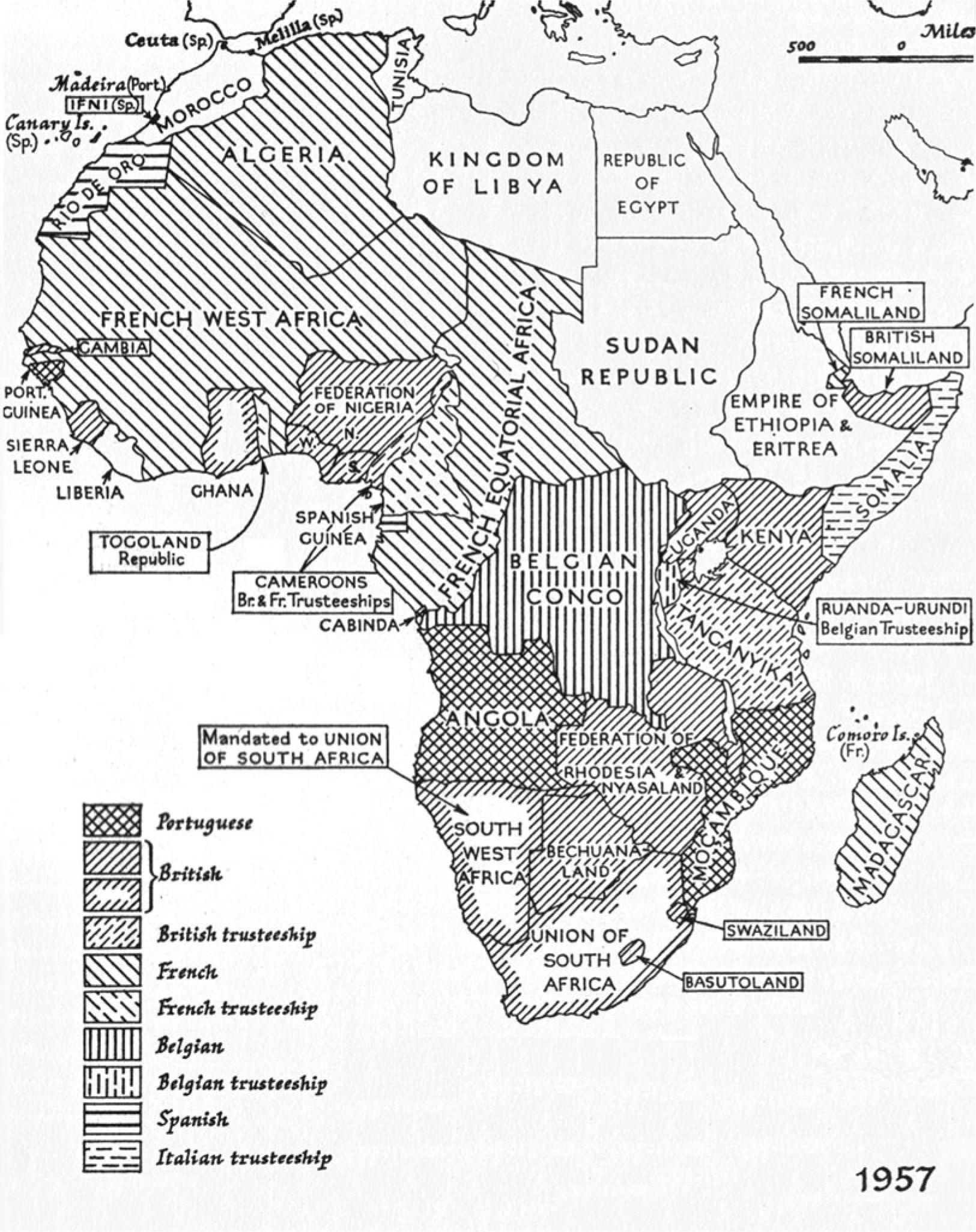

For the majority of education-seeking travellers, however, reaching Khartoum, Cairo, and the Eastern bloc was a highly complicated affair, which hardly conformed to the image of a unidirectional, fast-track, ‘well established pipeline’ invoked by colonial observers.Footnote 40 The journey involved the passing of checkpoints, myriad overland bus journeys and train rides, boat trips on the Nile, and visits to embassies for visas (see figure 2). Sojourns, twists, turns, and disappointments were features of these highly contingent trips. To start the journey, many sought out relatives and friends of relatives; along the way, many entered into informal labour arrangements, or found ways to get support from strangers and people of the same faith, ethnic group, or origin. With old and new acquaintances, they made ends meet in Ugandan and Sudanese towns.Footnote 41 Some made their way to Europe, for instance through airlifts to Moscow or another eastern European capital. For others, these journeys took up to several years, and led to temporary dead ends, or to other destinations.Footnote 42

Figure 2. Countries and towns along the ‘Nile route’, 1961. Source: adapted from Hel-hama, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:River_Nile_map.svg, ‘River Nile map’, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/legalcodelicense: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Trajectories also depended on the identity of travellers, especially the reading of identities at borders posts. As Luise White and Miles Larmer have argued, ‘borders did not always stay open’: they ‘moved through time and across people and political affiliations’.Footnote 43 In the case of the ‘Nile route’, this was particularly true at borders between dependent territories and independent states. The small town of Gulu, in northern Uganda, was a central place of passage for travellers heading from dependent East Africa towards independent Sudan. Gulu was a place where young travellers negotiated their status, identity, and credibility with suspicious Special Branch interrogators.

Depending on how regional origin, race, and ethnicity were performed and evaluated, borders could be insurmountable or porous. The Acholi living in northern Uganda, for instance, were allowed to pass, because members of this ethnic group also lived on the Sudanese side of the border.Footnote 44 In contrast, the Zanzibari Adam Shafi reports from his journey to Cairo that, after having been stopped (not for the first time) by a police officer on the Ugandan side, he was brought to a police station for interrogation. The white police officer held him to be a Kikuyu, implying the accusation that he might be involved in the anti-colonial activities of the Mau Mau in Kenya. Shafi only got permission to proceed when he produced a birth certificate, proving that he was an ethnic mngazija (Comorian) from Zanzibar. His two travelling companions, who had a lighter skin than Shafi (but also saw themselves as Zanzibaris), were usually perceived as Arabs along the journey, and did not experience similar problems.Footnote 45

Reading these border crossings of a newly mobile group of East African youths as a pre-stage to communist infiltration, the British exerted pressure on postcolonial Sudan to put an end to student migration. Shafi was pulled out of the crowds again in Nimule, on the Sudanese side of the border, which might have been related to British power politics influencing Sudanese authorities, following intelligence reports of increasing numbers of East Africans crossing from Uganda into Sudan. In February 1960, the British ambassador in Khartoum informally agreed with Sudanese regional authorities that the latter would repatriate any students found in Nimule or Juba without valid papers.Footnote 46 Sudanese government detectives roamed the streets of Nimule and Juba with the sole task of catching students heading towards Khartoum. Detectives intercepted dozens of travellers, many of whom tried again and again, until they managed to slip through the controls and proceeded to Khartoum. Blending in with the local populace was a key strategy. As a Special Branch report noted, students dressed in the kanzu (a white robe) worn by men in the region to pass as Sudanese, or as members of ethnic groups living on both sides of the border, who were permitted to visit the Juba area without a pass. Young men perceived to look less ‘Lango’ or ‘Acholi’ and more ‘Bantu’ or ‘Baganda’ were stopped, and turned back.Footnote 47

A more conventional colonial strategy to regulate mobility, and to gather information about colonial subjects’ journeys, was the issuing and withholding of passports. In Zanzibar, for instance, trade union members suspected to be departing for the Eastern bloc had their passports seized, while Kenyans whose eastward travel plans became known to authorities faced arrest.Footnote 48 Apart from students, intermediaries were targeted as well. The British withdrew the passport of the Ugandan politician Otema Allimadi, who had handed out several scholarships from communist countries, in order ‘to make it more difficult for him to organise the clandestine travel of students through the Sudan to take up scholarships behind the Iron Curtain’.Footnote 49 The new political situation meant, however, that even travellers without a passport stood a chance of reaching their destination. Once they had moved out of imperial spaces and into independent African states sympathizing with anti-colonial movements, they could count on the assistance of North African or communist states, which would furnish them with new travel documents.Footnote 50

There were three important channels through which young East Africans received crucial information about new destinations and routes: anti-imperialist radio broadcasts, personal networks, and political entrepreneurs. Radio was the most important medium for spreading anti-colonial nationalism. Radio India and Radio Moscow aired anti-imperialist talks in Arabic, Swahili, and other languages used on the continent, but no other station was as popular and effective as Radio Cairo in popularizing ‘cold war vocabularies and anticolonial bromides that satisfied colonial subjects’ growing hunger for polemics’.Footnote 51 Radio Cairo enabled the establishment of radio services like Voice of Kenya and Swahili-language broadcasts, in cooperation with Zanzibari students, which put Egypt on the map for growing East African audiences.Footnote 52

Personal contacts also helped to spread information. Students who had already taken up their studies behind the Iron Curtain sometimes wrote letters to their friends and relatives, providing guidance where to get a scholarship for the Eastern bloc and how to get there. Some of the correspondence – for example, the letter by the Tanganyikan student Arphaxiado Binagi writing from Hungary to his friends in Iringa (central Tanganyika) – was intercepted by British intelligence. Binagi boasted that he was preparing himself ‘for a long march to free Africa’. To let his friends also benefit from ‘a full knowledge of Communism, a 20th Century [sic] mighty power’, he furnished the names and addresses of contacts in the Sudan and Tarime, near Lake Victoria, Uganda, and advised them to keep all information secret.Footnote 53 Schools with more than ten alumni present in the Eastern bloc, such as a Gulu secondary school near the Sudanese border, whose former headmaster had studied behind the Iron Curtain, gained the reputation of being hotbeds of communist propaganda.Footnote 54

Apart from radio and personal contacts, politicians who served as middlemen between students and external providers of scholarships also supplied crucial information, and used their resources and social capital to arrange mobilities towards Egypt and the East. These ‘scholarship hawkers’, as they were disdainfully called by British officials, included E. Otema Allimadi, the Secretary-General of the Uganda National Congress (UNC), and Dr Barnabas Nyamayarwo Kununka, also from the UNC, who according to British information was in touch with Kenya’s first black lawyer and politician, Argwings Kodhek, another key facilitator for Kenyans’ journeys to eastern Europe.Footnote 55 The KANU politician Oginga Odinga claimed a central role in what he called the ‘historic trek of Kenya students’ to socialist countries. He boasted of disposing of hundreds of bursaries, which, as Daniel Branch noted, ‘allowed him to develop a source of patronage to rival the American scholarship programme built up by Mboya’ (discussed below).Footnote 56

The quantitative dimension of the Nile route is hard to pin down. Both nationalist politicians and colonial officers had incentives to overstate their estimates. Odinga claimed that by 1963, thanks to his efforts and cooperation from Cairo, Sudan, and Tanganyika, more than a thousand Kenyans had made their way to the socialist camp, but also to Italy, Canada, Great Britain, and the United States.Footnote 57 British intelligence officers pointed to the ‘ice-berg nature’ of eastbound mobilities, and felt that surveillance tasks would soon ‘swamp the existing administrative machine of Special Branch’.Footnote 58 The ‘Nile route’ revealed both colonial anxieties and colonial limitations of knowing. Between March and November 1960, the Special Branch in Uganda almost quadrupled its estimate of students in the socialist camp, from 17 to 64, while the number of students suspected of planning on leaving rose from 75 to 198.Footnote 59 Special Branch officers warned, with a tone of resignation, that ‘no security measures alone’ could possibly ‘interrupt for long the flow to Iron Curtain countries’, which was ‘likely to increase if unchecked’.Footnote 60

The numbers did not grow, however, as the first states in East Africa became independent. With Tanganyika’s independence in 1961, Kenyans, Ugandans, and exiles from southern Africa could now submit their scholarship applications to embassies and international agencies’ offices in Dar es Salaam.Footnote 61 The West German embassy in Dar es Salaam reported a genuine scramble between Chinese, Soviet, and US representatives, hunting for the most qualified exiles in the city to equip them with scholarships.Footnote 62 Largely because of these developments, the airlifts of East African students heading to North America eventually secured grudging imperial approval.

Airlifts to North America

The westward movement that was most significant in quantitative terms, the ‘airlifts’ of more than 800 East African students to the United States and Canada between 1959 and 1961, resulted from the combined initiative of Kenyan nationalists and communities, as well as philanthropic foundations, universities, pan-African leaders, and civil society activists in North America. Many of the American colleges and universities ready to offer scholarships were historically black institutions. Colonial officials were concerned that scholarships from institutions with a ‘bad communist reputation’, such as Lincoln University, would exert a ‘most undesirable’ influence on students, but usually issued the required exit visas.Footnote 63 The initiatives, coupled with the growth of eastbound routes, eventually propelled US and colonial authorities to provide a larger number of scholarships.

Leaders of nationalist parties, such as Tom Mboya from Kenya and Julius Nyerere from Tanganyika, had already used their first US visits in 1956 and 1957 for stipend-shopping.Footnote 64 Mboya charged that the colonial ‘tapering pyramid’ educational system contained deliberate bottlenecks, to prevent the growth of a critical mass of individuals who would destabilize foreign rule. He thus sought to expand the educational repertoire for Africans.Footnote 65 In the US, he was particularly successful in getting church-run and historically black colleges to grant partial- or full-tuition scholarships.Footnote 66

Transport, however, remained a problem, as many who had acquired scholarships were not able to raise the funds necessary for the flight and immigration procedures. In 1956, Mboya contacted the millionaire industrialist and philanthropist William X. Scheinman and the real estate entrepreneur Frank Montero, who were involved with the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), established in 1953, and led by the anti-colonial activist and Protestant minister George Houser. The ACOA helped in getting about three dozen individuals to North America for schooling, and in establishing links to civil rights activists.

In 1959, this support was institutionalized, as Scheinman’s funds were channelled through the newly established African American Students Foundation (AASF). To add to Scheinman’s funds, Mboya and the AASF organized a fundraising campaign involving famous activists such as the actor Sidney Poitier, the musician Harry Belafonte, and the writer Langston Hughes, raising over US$35,000.Footnote 67 While the Eisenhower administration still refrained from offering substantial numbers of scholarships to colonial territories, in order to keep up good relations with the UK, Mboya had succeeded in enlisting a plethora of actors in East Africa and North America to run and finance a scheme that was privately funded and independent of colonial and US official supervision.

Although the costs for stipends and transport across the Atlantic were covered by external donors, the arrangements still proved highly selective in material terms. Aspiring students had to be able to afford their stay abroad. US immigration regulations required applicants for a student visa to dispose of US$280 in cash. Even for East Africans in a salaried civil service position, it was virtually impossible to raise this amount individually, as it equalled several times the average US$84 annual per-capita income of Africans in Kenya.Footnote 68 They needed the material and moral support from families, clans, villages, colleagues, or employers, a support that also went along with considerable social pressure to perform and reciprocate upon return. In some cases, relatives sold their land or ran up debts.Footnote 69 Many candidates also raised funds through fundraising campaigns, tea parties, and Harambee (‘Let’s pull together’) parties, all of which were usually co-organized by local politicians and trade unionists.Footnote 70 The private contributions gathered at these events were estimated to have surpassed USD$50,000. Finally, Tom Mboya persuaded the Aga Khan to donate US$5,000 to assist students in the first airlift, and similar amounts during the later airlifts.Footnote 71

Airlifts were thus the result of complex interactions and mobilizations of resources on local and regional levels, rather than just the outcome of competing Cold War offers. Seeing such collective (and possibly well-staged) fundraising events, with old women and small children donating pence, shillings, and even eggs to be auctioned, would convince official US delegates in 1960 of the ‘reverence these people showed for education’.Footnote 72 The delegation’s reports then formed the basis of the capture and further evolution of airlifts under the Kennedy administration. The airlifts thus exemplify the complex interactions between politicians, activist networks, ordinary Kenyans, and, only at a later stage, official government institutions that facilitated these journeys.

Being neither part of official colonial pathways nor belonging to clandestine routes with minimal assistance and arrangements, airlifts contained comparatively many female travellers. This illustrates the gendered dimension of the bars to higher education. In contrast to the male group of clandestine travellers on the ‘Nile route’ – mostly young, unmarried secondary school leavers, who were confident that they could navigate the risks of a clandestine journey – the Westbound ‘airlift’ cohort contained a larger share of women, some of whom had already worked as secondary school teachers and clerks.Footnote 73 Roughly one-fifth of all airlifters in 1959, and one-quarter in 1960, were women. This was a share considerably higher than average rates among ‘Third World’ students in the Western and Eastern world, and it also surpassed the percentage of female secondary school graduates in East Africa, where both authorities and parents privileged the education of boys.

According to Jim C. Harper II, the airlift’s unusual gender ratio was partly the outcome of deliberate efforts by Mboya and his associates to select more women. Given that few women had the formal standard of education necessary for direct admission to tertiary education, there were arrangements with North American high schools, which would serve as stepping stones to university.Footnote 74 Candidates could apply and were chosen by a selection committee consisting of Tom Mboya and his associates Julius G. Kiano and Kariuki Njiri. The committee members, who belonged to different ethnicities, had agreed to make their selection on the basis of meritocratic criteria. In practice, however, applicants (most of whom were Luo, like Mboya, or Kikuyu) often sought the patronage of the leader of the same ethnicity, or constituency (Mboya representing a majority Kikuyu constituency).Footnote 75 Successful applicants included Kikuyu who had been detained as supposed Mau Mau fighters, or who had been expelled from educational institutions for political subversion.Footnote 76

The airlifts immediately dwarfed the official scholarship programmes in quantitative significance. The US government programme had brought a mere five people from Kenya to the US in 1957, and only nine (two of whom were ethnic Poles) in 1958.Footnote 77 The 1959 airlifts, in contrast, facilitated the passage of eighty-one students. Playing the anti-communist card helped the AASF to obtain funds from the Kennedy Foundation (connected to the family of Senator John F. Kennedy, who was running his presidential campaign) in 1960, and from US and colonial authorities in 1961.

Several factors led the US government to step up its support and strive to replace the uncontrolled airlifts with officially sanctioned programmes. Up to 1960, the US government had provided large batches of scholarships to African countries only because of Cold War rivalries: for example, following Guinea’s independence and turn to the Soviet bloc in 1958, and the Congo Crisis in 1960. The scramble for Afro-American votes in the 1960 presidential campaign was another catalyst.Footnote 78 At the same time, there would have been far less attention to the demand for higher education without the efforts of Mboya and other activists. The colonial governments’ change of heart in Kenya, North Rhodesia, or Nyasaland was spurred by the fact that the movement towards the North and East seemed incontrollable, unless additional scholarship were offered. As the president of the AASF warned in 1960, the gap between the demand for scholarships and scholarships available would ‘certainly be completely bridged by … assistance from Iron Curtain countries which have tremendously increased their aid’, including supposedly 2,000 scholarships for Kenyans alone.Footnote 79 In contrast to travellers along the ‘Nile route’, many of whom did not reach their envisaged destination, most of the East Africans supported through the airlifts to North America successfully took up college or university studies.

Airlifters returned to their countries of origin upon completing their studies, often with a nuanced image of US society and politics. Several students requested a relocation to New Jersey University, after experiencing discrimination at colleges in the South, where they were sometimes the first black students on campus. A few Kenyans contributed to the desegregation of campuses, and became active in the growing civil rights movement.Footnote 80 Generally, political opinions remained diverse, and moderate rather than radical. The airlifter (and first black female African Nobel Prize winner) Wangari Maathai recalled that her stay in the United States sparked her commitment to gender equality, but also that she and other Kenyans who were studying in the Midwest were repelled, rather than inspired, by radicalism. Speeches at a Nation of Islam meeting she attended seemed to her, a devout Catholic, ‘not only untrue but also sacrilegious’.Footnote 81 Of the first generation of airlifters from 1959, 80% assumed leading positions in Kenya’s government, educational sector, and administrative apparatus. In the same cohort, only two returned after having failed, while only seven (9%) remained in the United States.Footnote 82

The Eastern bloc ‘exodus’

As debates about non-returning students and a ‘brain drain’ gained currency in the 1960s, Eastern bloc countries argued that this was a typically Western phenomenon, unknown in the socialist world. Indeed, generally students had to leave shortly after graduation, as they usually received no residence permit. However, this does not mean that they necessarily returned to their country of origin.Footnote 83 A striking phenomenon in the early 1960s was that hundreds of foreign students left Eastern bloc countries even before the end of their studies.

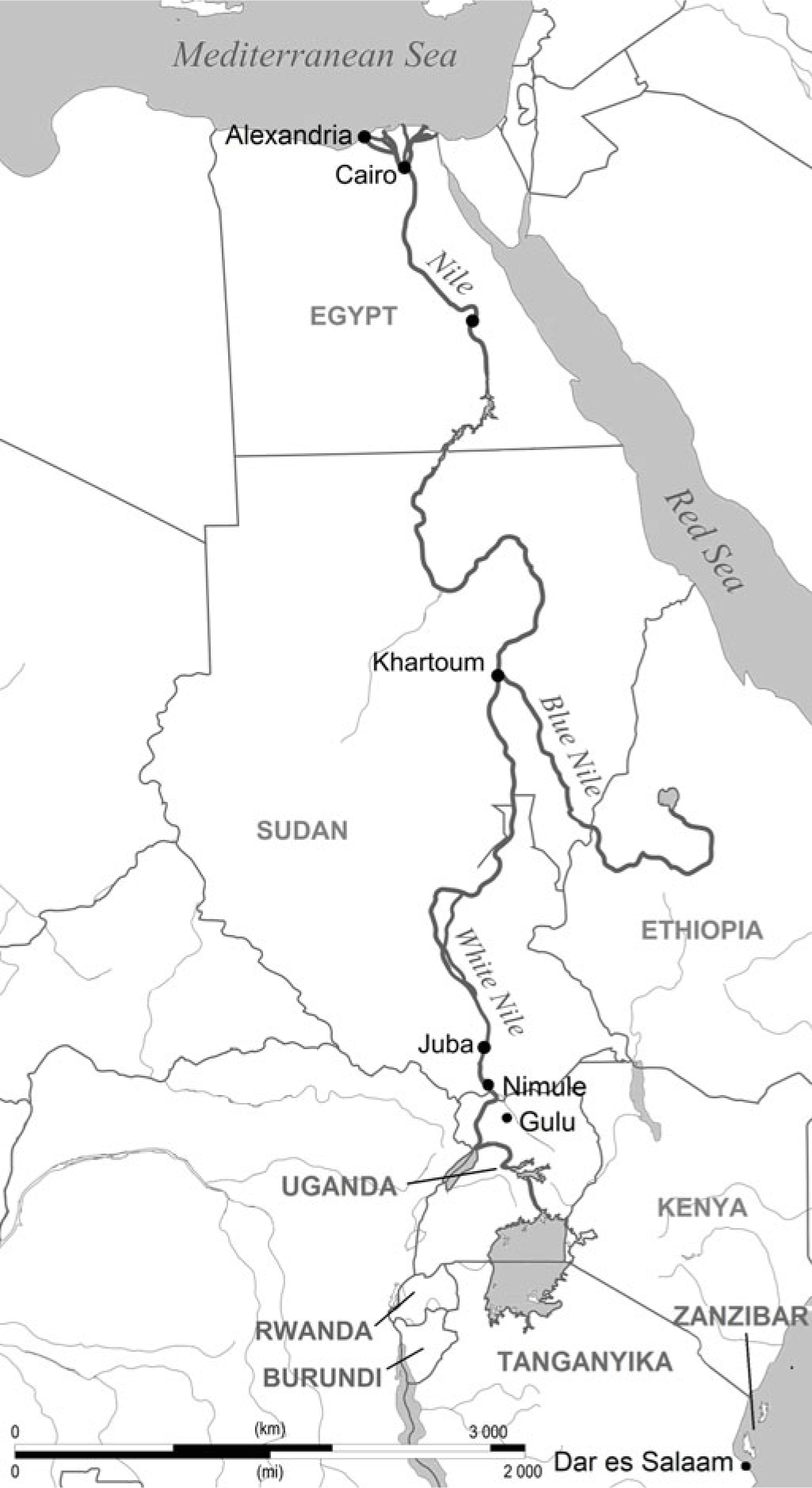

In 1962, West German media began reporting on a ‘new type of refugee’.Footnote 84 They registered the influx of growing numbers of what they called ‘Eastern bloc refugees from developing countries’ or ‘student refugees’ (Flüchtlingsstudenten). In 1963, as the number of arrivals and media reports increased, West German authorities realized that they could no longer ignore the arrival of ‘student refugees’. According to West German sources, 736 ‘Third World’ students defecting from Eastern bloc universities had come to West Germany between the late 1950s and November 1964 (see table 3). The Federal Republic was a key destination, and transit zone, in this movement of students across the Iron Curtain. In contrast to the UK or the US, West Germany was a border region and contact zone of the Cold War, and had to deal with a far larger number of new arrivals from eastern Europe. Crossing the Iron Curtain was possible via several routes. Many of the students coming from Bulgaria apparently travelled via Yugoslavia, and then took flights to western Europe, or went on to Italy.Footnote 85 Others crossed the border in Berlin.

Table 3. ‘Refugee students’ from the Eastern bloc (eastern European countries) registered until 1 November 1964 in West Germany. Data were collected by the Bundesstudentenring (BSR), the umbrella organization of student associations in the Federal Republic. The BSR’s own welfare section (Sozialamt) assisted arriving students

Source: Bundesarchiv Koblenz, B 213/438.

The majority of the 736 students who were registered in West Germany until November 1964 originated from sub-Saharan Africa (586); of these, 435 had arrived in 1963 and 1964. This was a challengingly high number: the 586 arrivals from sub-Saharan Africa equalled approximately half the number of Africans studying in West Germany at the time. Given that these figures do not include students who went to other countries, including the Netherlands, Austria, Italy, and France, the ‘exodus’ must be assumed to have been significantly larger.Footnote 86 In some ways, however, it was also smaller and quite different, as suggested by the statistics and accompanying media reports. Contrary to Western expectations, some of the ‘Eastern bloc refugees from developing countries’ returned to communist Europe, especially when they failed to get access to higher education.

The reasons for leaving the Eastern bloc countries in the first place were manifold, and differed between individuals and countries, though certain motives were widespread. In several countries, African students voiced resentment regarding the denial of the right of political self-organization, officials’ reluctance to deal with domestic racism, shortages of consumer goods, and disciplinary expectations. In the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, and China, collective protests were triggered by strikingly similar events that catalysed these tensions. In China, in 1962, African students protested with sit-ins and hunger strikes against the beating of an African student; eventually, only 22 of the original 118 remained.Footnote 87 The largest protests in the Soviet Union (Kiev 1962, Moscow 1963, Baku and several other cities 1965) were all preceded by the deaths of African students under circumstances that, in the eyes of the protesters, smacked of racism.Footnote 88 In December 1963, during the first public protest on the Red Square not sanctioned by authorities for decades, demonstrators would call Moscow the ‘second Alabama’. In February 1964, the West German embassy warned authorities in Bonn that more than a hundred Tanganyikans who had protested about conditions in the Soviet Union were on their way to West Germany.Footnote 89

This number never arrived in the Federal Republic (see table 3), suggesting that not all protesters in Moscow actually left. Most probably arrived from Bulgaria in 1963, where tensions over living conditions and racism had erupted after the authorities had refused to register a pan-African student organization in March. Between 350 and 500 students, the majority of African students in the country, left.Footnote 90

These protests and departures sent ripples through the Cold War world, for example in East Germany. Both African students and officials there were aware of the events in Moscow and Sofia, through reports first in Western and African media, and later also in those of eastern Europe.Footnote 91 East German functionaries, predictably, blamed the protests in Moscow and Sofia on Western influences, and on the bourgeois origins of students. They feared that the Union of African students in East Germany (UASA) would spark similar protests by referring to the events in Bulgaria at an upcoming conference. They thus convinced the union’s leaders to leave ‘Sofia’ (as the events were called) unmentioned at an upcoming conference.Footnote 92

‘Sofia’ also surfaced when students voiced their protest against racism encountered in the West. In the West German federal state of Hessen, where the US army was stationed, white US soldiers not only regularly got into bar brawls with African students, but also sent letters to Ghanaian student representatives, in which they threatened to ‘lynch’ them. The US ambassador voiced a public apology.Footnote 93 The West German embassy in Accra reacted to complaints of Ghanaian students about West German professors’ racist behaviour, and warned of a looming ‘Russian- or Bulgarian-style exodus of African students’.Footnote 94 Most Western authorities, however, were prone to interpret and, by extension, delegitimize criticism of racism in their countries as communist propaganda.Footnote 95

Dichotomizing Cold War categories concealed the diversity and complexity of students’ personal motives. Many of the hundreds who left for Western countries in those years cited political reasons and racism for their decision to leave the Eastern bloc.Footnote 96 Portraying themselves first and foremost as victims of political oppression and racist discrimination enabled them to capitalize on anti-communist sentiments in western Europe, which was a language that was easily understood. However, while West German activists and supporters of the refugees also highlighted these dimensions, government officials suspected that a large percentage of the arrivals had simply failed their examinations, or were dissatisfied with living standards or the non-academic courses they had been assigned to, aspiring to become doctors and engineers rather than mechanics and dental technicians.Footnote 97 Evidence suggests that expectations of upward social mobility were indeed an important factor. As shown above, this had been the primary motivation for some to look for opportunities beyond East Africa. Many left East Germany (and other communist states) because they had expected to attend a full university degree course, rather than semi-academic trade union education, or vocational training. Alternatively, they perceived these courses (correctly, in a few cases) as springboards to university.Footnote 98

Others failed to cope with academic standards. Not in all cases could the Eastern bloc’s preparatory programmes make up for academic shortcomings, a result of recruitment based on political criteria, so that students were exmatriculated. In the case of Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba University, which had a particularly bad reputation as a political or substandard university, the drop-out rate amounted to 14.4% between 1960 and 1968, including voluntary drop-outs and no-shows after holiday, as well as expulsions for disciplinary reasons and academic failure. It is likely that going to the West seemed more attractive than returning home without a degree for most of these students, especially as degrees from Lumumba University were not recognized in many African countries.Footnote 99 Given these circumstances, even those who had graduated sometimes opted for the Western option, rather than a direct return to the country of origin.

Officials in the West perceived the students defecting from the Eastern bloc primarily as ‘political capital’, and sought to exploit the ‘political propaganda value’ of their experiences.Footnote 100 The propaganda battle was fought in newspapers, magazine articles, and books. A preferred format was the seemingly authentic and direct first-person account based on experience.Footnote 101 A major function of the publications was not just to engage Western audiences, but also to dissuade other Africans from going to the Eastern bloc. The Soviet Union responded by publishing accounts such as Christopher Rwezahura’s A Tanzanian in Moscow (also published in Kiswahili as Mtanzania katika Moscow), a rather inelegant piece of propaganda waxing on about a perfect experience in the promised land of socialism.Footnote 102 East German functionaries also saw applications and requests for support by discontented Africans in West Germany as an excellent opportunity to expose the West’s defects, juxtaposing them with the achievements of socialism.Footnote 103

Yet, as the British Foreign Office informed British embassies from Beijing to Washington, many African students were not ready to be instrumentalized as pawns in a Cold War game, nor did their experiences always yield fodder for ideological crusades. One student from Uganda proved to have ‘no detailed complaints about his experiences in Russia, to have no interest in politics and to be only concerned to further his own education’. Two Ugandans had first signalled readiness, but then ‘placed restrictions on the exploitation of the experiences in publicity’. A piece published in the Sunday Telegraph by A. G. Okotcha, a Nigerian who had studied at Moscow’s People’s Friendship University, did not fulfil the authorities’ expectations, and was found to be ‘marred by obvious distortions’.Footnote 104 This limited the exploitability of the ‘exodus’, and helps to explain why Western states, West Germany in particular, eventually sought to reduce rather than increase the number of westward departures.

West German officials were initially reluctant to deal directly with the issue, and they let student and civil society organizations take care of the arriving students. The most important institution in this regard was the federal student union in the Federal Republic, the Bundesstudentenring (BSR). The BSR’s own welfare section (Sozialamt) registered, screened, and assisted arriving students in West Berlin. Nevertheless, in 1963 and 1964, the Foreign Office supported the arriving students, including the so-called ‘Sofia Group’, at the cost of DM800,000 a year.Footnote 105 At the same time, these young people were considered as potentially undeserving in terms of education, or even as a threat. Officials suggested that those who received support should be re-educated and undergo anti-communist courses offered by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.Footnote 106 A range of unlikely categories cropped up in efforts to sort the students into desirables and undesirables. One West German official stated that 30% of the student refugees were ‘negative cases’, including ‘those more or less taken indiscriminately from the bush’, ‘those suffering from a venereal disease’, students evading alimony payments, students with a criminal record, ‘intellectual failures’, and, finally, Berlin-based ‘escape agents’, who followed either idealistic or commercial motives.Footnote 107 These categories reflected officials’ anxieties and racist assumptions around classic themes of migration management, including security, hygiene, border control, sexual contamination, and moral judgement.

It was also suggested that West Germany should only consider supporting those students covered by intergovernmental agreements, and deport all those sent by ‘communist front organisations’.Footnote 108 Authorities wanted to capture promising proto-elites, and send home all others who might turn out to be academic failures and a financial burden. Between November 1962 and November 1963, 350 persons had been brought to the refugee camp in Wickrath, in North Rhine-Westphalia, where they were registered and subjected to academic tests. Of these 350, 32 were deported (with transport costs funded by the United States), 40–50 disappeared after their hopes for a scholarship in West Germany had been shattered, 40 were relayed to third countries in the West, 140 acquired scholarships or access to courses that would enable them to enter university, 60 remained in Wickrath for ongoing tests, and 30 returned to eastern Europe.Footnote 109

West German policy changed in 1964 to a resolutely restrictive stand. In the early 1960s, the ‘Eastern bloc refugees from developing countries’ had stood a fair chance of acquiring scholarships from official sources, but in April 1964 the West German Minister of Foreign Affairs put a lid on budding initiatives, welcoming gestures, and requests for further funding. Expecting that the arriving groups comprised not only stellar students but also, and perhaps mainly, undesirable and poorly qualified young foreigners, he saw incentives as counterproductive. His main argument, apart from material considerations, was that the ‘ferment’ (Gärungsferment) of frustrated foreign students would ultimately weaken communism, if only it was left to cause trouble behind the Iron Curtain, without an ‘outlet’ to the Western world.Footnote 110 This political decision implied that no additional resources would be allocated for dealing with these students coming from the East. While the Iron Curtain remained porous, special efforts to lower the requirements for scholarships were discontinued.

Asylum was, however, still granted to those Africans who could convince West German authorities that they were at risk. Again, framing the request in anti-communist terms was important here. One Zanzibari, for instance, claimed that the GDR had exmatriculated him and withdrawn his scholarship for political reasons, after an open protest against the firing order at the Wall. He claimed that, given the close relations between East Germany and Zanzibar, he faced persecution in his home country.Footnote 111 Tapping into West German perceptions of Zanzibar as being ‘communist’ was effective.

In contrast, some also returned to the other side of the Iron Curtain. From the group of twenty Ghanaians who had left the GDR following the request of the military government, eight returned and (successfully) requested permission to continue their studies in Leipzig. In their written and signed declaration, they stated that, during their stay in the West German refugee camp in Wickrath, they had come to realize that their presence would be misused for political purposes, while at the same time no concrete steps had been taken to support their educational aspirations.Footnote 112 Washington Bomani, the brother of Tanzania’s government minister Paul Bomani, fled the GDR in 1964 for London, where he approached the West German embassy for a scholarship, promising that he would never return to a communist country.Footnote 113 The Foreign Office was willing to assist him. Soon thereafter, however, he returned to the GDR, reportedly because he had ‘not liked’ West Germany.Footnote 114 Apparently it was pragmatism, not Cold War allegiances, which drove many of these cross-border journeys.

The East–West movement of African students had become a reference point in the mind of officials and public opinion on both sides of the Iron Curtain, and these movements, together with persistent complaints, informed policy changes. East German authorities pushed for the improvement of living conditions and the tackling of racism, without actually acknowledging its existence, in 1964–65. Additionally, they had drawn a lesson from the admittance of candidates whose academic credentials were below standard requirements. Officials were now convinced that these candidates, no matter if delegated by state institutions or arriving via other channels, would in most cases cancel their studies and become frustrated; they would either leave or perform badly academically, both of which damaged the GDR’s reputation.Footnote 115 A 1965 list of exmatriculated foreign students in the GDR shows that almost all had their studies discontinued because of poor performance.Footnote 116

At the same time, Africans continued to send letters from France, the UK, and West Germany applying to study in the GDR, usually without any particular reference to ideological aspects or superpower rivalries.Footnote 117 The Eastern bloc remained a sought-after destination for those who failed to realize their aspirations in the West, owing to financial, academic, or political reasons. East–West migration also continued. Kenyan authorities, for instance, requested West German institutions to include Kenyan ‘refugees’ from the Eastern bloc in their scholarship programmes as late as 1967.Footnote 118 In general, however, movements across the Iron Curtain in both directions became less significant after 1965. By then, the ‘Nile route’, the airlifts, and the Eastern bloc ‘exodus’ had brought about lasting legacies of global interconnectedness.

Conclusion

East Africans seeking access to higher education broadened the repertoire of migration in the late 1950s and early 1960s, by making use of overlaps between Cold War rivalries and accelerating decolonization. In contrast to the dominant picture in the literature, the routes discussed cannot be simply seen as the result of state-led initiatives and superpower competition in terms of Cold War policies: they were shaped by African politicians and youths navigating constraints and opportunities as they forged new pipelines, knit new networks, and exploited the openings that the Cold War and the first successes of decolonization offered.

These openings were limited, however. Mobilities along clandestine and semi-official routes propelled state actors to shape, channel, regulate, and constrain these novel movements according to their interest, which is why all of these alternative paths to education were comparatively short-lived. They had important effects nevertheless. Colonial and superpower officials evaluated the mobilities through a Cold War mindset, and made efforts to control educational migration and improve offers, temporarily believing that more scholarships were an effective counter-measure.

Yet Cold Warriors erred in their view that education was a zero-sum game of producing either capitalist or socialist graduates: students’ pragmatism and objectives of personal advancement frequently undermined the policy objectives of nationalist politicians and receiving states. As the movement between East and West demonstrates, many students felt at ease using the Iron Curtain’s porosity and ideological rivalries productively, rather than succumbing to the dichotomous views of the superpowers. At the same time, pragmatic strategies of seeking access to higher education did not rule out political goals; on the contrary, they were often framed in anti-imperialist, nationalist, pan-Africanist, or socialist terms, which points to the anti-colonial content of these educational avenues.

Given that a good part of the incumbent generation of postcolonial elites had studied overseas, the clandestine and semi-official routes also decisively shaped the transformative years at the threshold to independence. In Kenya, for instance, Mboya’s westbound and Oginga’s (predominantly) eastbound routes firmly established rival political dynasties in the country. Returnees from the socialist camp, suspected of propagating Marxist-Leninist ideology, or even violent revolution, had a hard time finding a job. Excluded from reaping the benefits of their education as their counterparts returning from North America filled the ranks of the civil service, parastatal companies, and the ‘Africanizing’ private sector, they were more likely to support KANU’s radical faction.Footnote 119 Cosmopolitan Zanzibari leftists and their followers, trained in the Eastern bloc, China, or Cuba, had a profound impact on their country’s socialist orientation following the 1964 revolution.Footnote 120

Regardless of ideological orientation, postcolonial governments also made increased efforts to control educational mobility, take hold of the state’s educated elites, and subject them to the project of nation-building. Fears of political subversion through educational routes characterized both colonial and postcolonial governments, whether ‘progressive’ or ‘reactionary’. However, even when national commissions supposed to streamline educational mobilities were put in place, official institutions could not fully control the outflow of students, nor correctly estimate their number.Footnote 121 After independence in 1963, the Kenyan ambassador in Moscow admitted that he knew neither how many Kenyans were present in the Soviet Union, nor how many kept going there ‘through the backdoor’.Footnote 122 However, as more and more countries became independent, and as the Eastern bloc states increasingly worked through bilateral state agreements, educational migration towards the communist world became more regulated. This signalled the new dominance of official institutions in the ‘golden age’ of scholarship provision.

Eric Burton is Assistant Professor in Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck. He specializes in the entangled histories of decolonization, development, educational migration, and socialisms. Previously, he was a postdoctoral research associate in the project ‘Socialism goes global’, University of Exeter, a Leibniz EEGA Science Campus guest scholar at Leipzig University, and a pre-doc researcher and lecturer at the University of Vienna.