Abstract

Empirical studies on work-life balance (WLB) among employees without disabilities are abundant; in contrast, insufficient research exists on WLB and quality of life issues among employees with physical disabilities from Asian countries. This study used a nation-wide survey to examine how job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships were positively associated with life satisfaction among employees with physical disabilities in South Korea. The results of the study demonstrated that job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and family and friend relationships contributed significantly to the life satisfaction of employees with physical disabilities. Job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction were positively correlated (Pearson’s r = .606). Participants who were satisfied with job and leisure were 16.86 times [95% confidence interval (CI): 10.04–28.31)] more likely to be satisfied with their lives compared to those who were not satisfied with either their jobs or leisure activities. Participants satisfied with either their jobs or leisure activities were 4.49 times (OR 4.49, 95% CI: 2.64–7.65) more likely to be satisfied with their lives compared to those not satisfied with either their jobs or leisure activities. These findings suggest that managing a healthy balance between work and leisure may are critical to enhancing life satisfaction among the population with disabilities. Future research should include cross-cultural studies with sub-dimensions of the measurement scales to improve life satisfaction in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Previous studies on disability and quality of life provide evidence that employment enhances well-being, health-related quality of life, and life satisfaction among people with physical disabilities (Barišin et al. 2011; Vestling et al. 2003). For people with physical disabilities, work is not only a means of financial support but also a source of identity (Hay-Smith et al. 2013; Hammell 2007). Furthermore, being employed provides a sense of normalcy and opportunities for socialization (Saunders and Nedelec 2014).

However, previous research revealed that employed people with physical disabilities have experienced social discrimination because of their disabilities and were less likely to be satisfied with their jobs compared to the general population (Kaye et al. 2011; Uppal 2005). With the implementation of The Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, disability discrimination is prohibited in any aspect of employment, including hiring, firing, assignment of duties, pay, and promotions (EEOC 2020). However, employment conditions and opportunities to demonstrate job competence are still discriminatory and negatively affect job satisfaction (Chamberlain and Hodson 2010; Kulkarni and Lengnick-Hall 2011). Prior studies found that job satisfaction is positively associated with life satisfaction and quality of life among employees with physical disabilities (Park et al. 2016; Wu 2008), implying that job satisfaction contributes to the quality of life (Park and Kim 2015; Schönherr et al. 2005).

Another essential variable is leisure satisfaction. Previous studies demonstrate that high leisure satisfaction predicts greater life satisfaction among people with physical disabilities (Coyle et al. 1994; Kinney and Coyle 1992). In particular, a positive leisure experience for employees with physical disabilities is beneficial to maintaining physical health, healthy relationships with family and friends, and productivity at work (Cook 2012; Cook and Shinew 2014). However, few qualitative studies exist, and empirical research is lacking on how leisure contributes to the quality of life among disabled workers.

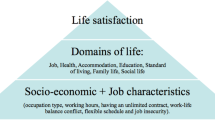

In contrast, research on work-life balance (WLB) among people without disabilities is abundant (Brough et al. 2014; Kalliath and Brough 2008; Sirgy and Lee 2018; Zheng et al. 2015). WLB is described as juggling various aspects of one’s life at any one point in time, namely work, family, friends, health, and self (Byrne 2005). Additionally, one’s satisfaction with leisure activity is considered a strong source of mediating work and family stressors (Knecht et al. 2016; Kong et al. 2020).

These findings suggest that Job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction contribute to life satisfaction among employees with disabilities. However, empirical WLB research that addresses both these variables simultaneously in this population is limited. It is therefore necessary to further explore the relationship between job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction, and to include social satisfaction as part of this analysis.

Although the definition of WLB is widely explored in the literature, there is no standard definition. Kalliath and Brough (2008) reviewed six conceptualizations of WLB commonly found in the literature. Of those six definition of WLB, this study adopted a definition of WLB as achieving satisfying experiences in all life domains (Kirchmeyer 2000). The purpose of this study is to investigate how job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships affect life satisfaction among employees with physical disabilities. We examine how life satisfaction changes with job and leisure satisfaction, and when only one of those variables is considered.

Literature Review

This section presents the theoretical frameworks in the literature regarding the effects of job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and family relationships, and friend relationships on life satisfaction among people with physical disabilities.

Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

Over the past decade, more research has examined the job satisfaction of people with disabilities, which contributes to life satisfaction and quality of life (Akkerman et al. 2016; Cho et al. 2011; Park and Kim 2015). Cho et al. (2011) found that job satisfaction was the strongest contributor to life satisfaction among employed people with physical disabilities. Moreover, Schönherr et al. (2005) found that dissatisfaction with a job was associated with a reduction in quality of life among people with physical disabilities.

Park et al. (2016) reported that employment status (e.g., permanent, temporary) were significantly associated with job satisfaction. Furthermore, Kim et al. (2014a) determined that welfare benefits were significantly associated with job satisfaction among employees with physical and mental disabilities. Also, they found that access to facilities, welfare benefits, and flexible working hours might lead to increases in job satisfaction among employees with disabilities (Kim et al. 2014a).

Interestingly, Pagan (2017) found that being overworked can lead to lower job satisfaction among female employees (with and without disabilities), and its impact is higher for employees with disabilities because they typically require more time for personal and medical care-related activities. Pagan suggested that being overworked reduced job satisfaction among female employees (with and without disabilities). Improvements in the quality of employment are essential to enhancing job satisfaction and life satisfaction among employed people with physical disabilities (Kim et al. 2014a; Choi 2017).

Also, prior research reports that social relationships in the workplace (e.g. social support from coworkers, supervisors, etc.) play an important role in mental health and well-being in people with physical disabilities (Tough et al. 2017). Social relationships with colleagues positively or negatively affect the Job and Life Satisfaction of employed people with physical disabilities (Chamberlain and Hodson 2010; Kulkarni and Lengnick-Hall 2011; Villotti et al. 2018). For example, emotional and instrumental support like task assistance from coworkers and supervisors improves their productivity (Kulkarni and Lengnick-Hall 2011) and confidence in facing job-related problems (Villotti et al. 2018) among employed people with disabilities. On the other hand, several studies have reported that employed people with disabilities are often excluded from group collaborations by their coworkers (Chamberlain and Hodson 2010), are given fewer opportunities to improve job performance (Kulkarni and Lengnick-Hall 2011). As a result, they experience social withdrawal (Chamberlain and Hodson 2010) and damage to their self-esteem (Holloway et al. 2007).

Leisure Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

Various studies reported that leisure is significantly associated with life satisfaction among people with disabilities (Hartman-Maeir et al. 2007; Kinney and Coyle 1992; Nimrod 2007; Tasiemski et al. 2005). Regular leisure participation is positively associated with stress coping, adjustment, and personal growth for people with disabilities (Cicerone and Azulay 2007; Duvall and Kaplan 2014; Kleiber et al. 2002; Loy et al. 2003). Giacobbi et al. (2008) interviewed people with physical disabilities who regularly participated in wheelchair basketball and found that they had a better body image, physical health, subjective well-being, and social relationships. For employed people with disabilities, Cook (2012) conducted in-depth interviews with employees with physical disabilities and revealed that their active leisure participation and high social support from family and friends contributed significantly to their job satisfaction and the vitality of life. Given that employed people with physical disabilities experienced unique and greater job strain due to their disabilities, such as managing chronic pain and fatigue, workplace activity limitations, and relationships with coworkers (Gignac et al. 2007), active leisure participation is a useful vehicle for dealing with job stress among employed people with physical disabilities.

Research suggests that the serious pursuit of leisure activities can be a work-like activity because it is challenging, improves social status, and develops social relationships for unemployed people with disabilities (Aitchison 2003; Patterson and Pegg 2009). Stebbins (1982), a leisure scholar who has adopted the term “casual leisure and serious leisure”, described casual leisure as an activity requiring minimal to no specialized training (e.g., watching TV). Serious leisure, in contrast, requires substantial time, effort, skill, and commitment. Unfortunately, the amount of leisure time is not always directly proportional to life satisfaction. Given that leisure time over a specific level negatively affected all sub-factors of happiness—such as friendship, achievement of goals, sociality, and acceptance of changes (Lee and Hwang 2014)—the quality of leisure is more important to subjects’ happiness than the amount time for leisure after the basic needs of leisure participation have been met.

Satisfaction with Family and Friend Relationships and Life Satisfaction

The quality of interpersonal relationships that people with physical disabilities have with their families (in the household or extended), friends, and acquaintances influence life satisfaction (Felce and Perry 1995). Social support from family was positively associated with life satisfaction, a reduction in depression, and psychological well-being among people with physical disabilities (Fuhrer et al. 1992; Horowitz et al. 2003; Schulz and Decker 1985). People with physical disabilities experience emotional intimacy in their families (e.g., Chun and Lee 2008), which is the core of their relationships (Hassebrauck and Fehr 2002). Post et al. (1998) examined levels of life satisfaction of people with physical disabilities compared to a control group. The authors found that people with physical disabilities had lower mean scores on overall domains (e.g., general life satisfaction, leisure situation, vocation situation, sexual life, and satisfaction with self-care ability) than the control group, but higher satisfaction with family life. Thus, close family relationships have a significant influence on life satisfaction among people with physical disabilities.

Relationship between Work and Leisure

Work is inextricably interwoven with other aspects of life, such as family and leisure (Watkins and Subich 1995). In the mid-1900s, scholars focused on the work-centered perspective, which suggests that work spills over into leisure. They considered leisure to be less important than work and an only area to compensate for dissatisfaction with work (Snir and Harpaz 2002). Leisure participation was often viewed as a negative idea and as an oppositional notion of work. However, since the 1980s, the available literature on leisure and quality of life has grown. Research has demonstrated that jobs in contemporary society often lack meaning and are difficult, so employees tend to focus on leisure activities (e.g., travel with family) rather than work to improve their overall quality of life. Naude et al. (2012) suggested that leisure activities had a strong effect on the overall quality of work-life among employees.

For example, studies among employed people with spinal cord injuries, Schönherr et al. (2005) found that a reduction in working hours was partly compensated for by an increase in leisure time. Furthermore, Petrovski and Gleeson (1997) demonstrated that there was partial support for a spillover effect on job satisfaction and psychological health (self-esteem, stigma, loneliness, and aspirations). These results suggest that these two variables are interrelated.

To achieve the purpose of this study, the 2018 Panel Survey Employment Data in South Korea was used to evaluate the impact of job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, family relationships, and friend relationships on life satisfaction among employees with physical disabilities in South Korea. Most previous research focused on Western cultures (Cook 2012; Cook et al. 2016; Cook and Shinew 2014), while only a few studies focused on Asians. South Korea is a developed country, one that is transforming from a work-oriented to a leisure-oriented society. It still has a robust work-based culture, but many people yearn for leisure and actively spend money and time pursuing it (Kim et al. 2014b). Accordingly, the desire for leisure activities among people with disabilities is increasing. Unfortunately, there is insufficient research that examines the holistic quality of life, ones that include family, friends, and leisure and work. Therefore, this study is unique and broadens the literature that examines the quality of life for employed people with physical disabilities who are living in Eastern countries. Furthermore, it may contribute to advancements in policies and practices as they relate to that quality of life for employees with disabilities.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

The data were obtained from the 2018 Panel Survey of Employment for the Disabled in Korea (PESD). The PSED is the first nationally representative longitudinal survey of people with disabilities in South Korea. The nationwide data were collected using a computer-assisted personal interviewing program (CAPI). The PSED sample consisted of a population of people who have one or more of 15 types of disabilities, aged 15 to 64, who have lived in South Korea since May 15, 2016. The survey includes demographic data (gender, age, education, disability status, disability grade, disability type), and data regarding economic participation.

Study Participants

The initial sample of 2018 PSED consisted of 4577 people with 15 types of disabilities, of which 1989 were people with physical disabilities. 927 people represent our studies baseline. Those 927 people represent the employee group, out of the 1989 total number of people with physical disabilities (Fig. 1). A total of 36 individuals were removed from the 927 participants due to incomplete data, resulting in a total of 891 participants. In brief, 891 of the 927 samples were used, meaning almost 96.1% of the samples. Therefore, results based on 96.1% of the sample can be regarded as representative of the population.

Each participant was identified with a physical disability and was between age 19 and 66, of which 708 (79.5%) were male and 183 (20.5%) female. Moreover, 416 (46.7%) participants earned more than a high school diploma, 751 (84.3%) were identified with mild disabilities, and 609 (68.4%) had been married or were cohabiting with a significant other. Additional participant demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Measurements

Independent Variables

The independent variables were job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction. These variables were assessed using single-item measures, such as “Are you satisfied with your current job?” and “Are you satisfied with your leisure activities?” These items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree.” Higher scores indicated higher levels of agreement.

Confounding Variables

The confounding variables were satisfaction with family relationships and satisfaction with friend relationships. These variables were assessed using single-item measures, such as “Are you satisfied with your family relationships?” and “Are you satisfied with your friend relationships?” These items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree.” Higher scores indicated higher levels of agreement.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Variables

Demographic variables included age, sex, marital status, degree of disability, cause of disability, and regular medical treatment related to disability. Marital status was categorized as married, single, and other (e.g., divorced, legally separated, widowed, etc.). The degree of disability was categorized into mild or severe. The cause of disability was categorized into congenital or acquired. Regular treatment of disability was categorized into yes or no.

Socioeconomic variables were level of education, the status of employment, number of household members, and annual income. Education attainment was categorized into middle school or less (< 7–9 years), high school (10–12 years), and any collegiate attendance (> 13 years). Employment status was categorized into temporary or permanent. Household members were categorized into 1, 2–3, and 4–7 (no participants lived with eight or more household members). Annual income was categorized into low (< $10,000), middle-low ($10,000–$24,000), middle-high ($24,000–$36,000), and high (> $36,000).

Dependent Variables

Life satisfaction was assessed using a three-item measure. Sample items were “Are you satisfied with your life?,” “Are you satisfied with your health status?,” and “Are you satisfied with your residential accommodations?” The item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly satisfied.” Higher scores indicated higher levels of satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.707.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, correlational analyses (Pearson correlations), and multiple regression analyses were performed to identify how job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships were associated with life satisfaction. The internal consistency reliability of each scale (i.e., life satisfaction) was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Multicollinearity was analyzed through tolerances and variance inflation factors (VIFs). There was no multicollinearity among the independent variables.

Logistic regression analyses were used to identify the contributions of every two independent variables to life satisfaction. To perform the logistic regression analyses, the independent and confounding variables and dependent variables were converted into binary classifications (0 = No and 1 = Yes) from the five-point Likert scale using a median split. For example, Job Satisfaction was measured using a 5-point Liker-type scale (1, strongly dissatisfied; 2, dissatisfied; 3 neutral; 4, satisfied; 5, strongly satisfied). The top two values (4 and 5) represented “highly satisfied,” and the bottom three values (1 to 3) represented “lowly satisfied.” The use of the median was because Job and Leisure Satisfaction variables were recorded using a 5-point Liker-type scale and measured using a single item (e.g. Fontanive et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2010; Milevsky et al. 2008). As a result, among the employed people with physical disabilities, 36.25% (n = 323) of those who were not satisfied with their jobs, and 63.75% (n = 565) of those were satisfied. In addition, 55.78% (n = 497) of the population were not satisfied with leisure activities and 44.22% (n = 394) were satisfied.

Furthermore, two independent variables were converted into four conditions. The first group represented having a low level of job and leisure satisfaction. The second group represented having a low level of job satisfaction with a high level of leisure satisfaction. The third group represented having a high level of job satisfaction with a low level of leisure satisfaction. The fourth group represented having a high level of job and leisure satisfaction. However, the second group had a small sample size (33 [3.7%] out of 891), so it was combined with the third.

Consequently, three groups were compared to determine the differences between the probabilities of being satisfied in life (Table 4). All variables were added into a logistic multiple regression model sequentially over four iterations. First, two independent variables were added. Second, demographic variables were added. Third, socioeconomic variables were added. Finally, confounding variables were added. The final analysis is a model to identify contributions of job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction to life satisfaction, including all relevant variables. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 software. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided with a p value of 0.05.

Results

Correlation Analysis

The correlation coefficient matrix (Table 2) illustrates that life satisfaction was positively associated with job satisfaction (r = 0.61, p < .01), leisure satisfaction (r = 0.61, p < .01), family relationship (r = 0.53, p < .01), and friend relationship (r = 0.54, p < .01). Job satisfaction was positively associated with leisure satisfaction (r = 0.61, p < .01). Among the demographic variables, age was inversely associated with life satisfaction (r = −0.08, p < .05). The degree of disability was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.09, p < .01). Regular medical treatment related to disability was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.15, p < .001). Among the socioeconomic variables, level of education was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.23, p < .01). Status of employment was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.20, p < .01). The number of household members was positively associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.09, p < .01). Annual income was associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.23, p < .01).

Multiple Regression Analyses

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to identify how job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships were associated with life satisfaction (Table 3). The demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, degree of disability, cause of disability, and regular medical treatment related to disability), socioeconomic variables (i.e., marital status, education, the status of employment, number of household members, and annual income), confounding variables (i.e., family relationship and friend relationship), and independent variables explained 57.6% of the variance in life satisfaction (F[14,876] = 84.933, p < .001, R2 = 0.569). In particular, employment status affected life satisfaction (β = 0.056, p < .05), however, annual income did not. Consequently, leisure satisfaction had the strongest impact on life satisfaction (β = 0.277, p < .001), followed by job satisfaction (β = 0.255, p < .001), satisfaction with family relationships (β = 0.203, p < .001), and satisfaction with family relationships (β = 0.185, p < .001). However, only a narrow margin was calculated between job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction. The following logistic regression analysis will help to identify more clearly the influence of two independent variables.

Logistic Regression Analyses

Independent t-tests and ANOVAs with post hoc tests (Scheffé) were performed to determine differences in the level of life satisfaction according to independent variables and confounding variables (Table 4). The results demonstrated that individuals who are individuals with high levels of satisfaction in leisure, job, and family and friend relationships had significantly higher levels of life satisfaction compared to those with low levels of satisfaction.

The logistic regression analyses revealed that individuals who were satisfied with both jobs and leisure activities were significantly more likely to be satisfied with life (Odds ratio [OR] 28.62, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 17.67–46.37) compared to those who were dissatisfied with both (Table 5). Even after including the demographic variables, socioeconomic variables, and confounding variables, the probability of being satisfied with life was higher (OR 16.86, 95% CI: 10.04–28.31). Furthermore, individuals who were satisfied with both jobs and leisure activities were significantly more likely to be satisfied with life (OR 6.45, 95% CI: 3.90–10.65) compared to those who were dissatisfied with one variable. Even after including the demographic variables, socioeconomic variables, and confounding variables, the probability of being satisfied with life was higher (OR 4.49, 95% CI: 2.64–7.65).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate how job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships were associated with life satisfaction among employed people with physical disabilities in South Korea.

First, multiple regression analyses indicated that job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships, and satisfaction with friend relationships were significantly associated with life satisfaction among this population. The results indicated that employed people with physical disabilities who live a balanced life, including leisure, family, and friend relationships, have a higher level of life satisfaction compared to those who only concentrate on their jobs. These findings are consistent with previous studies on WLB for employed people without disabilities (Haar et al. 2014; Kuykendall et al. 2017; Lee and Paek 2010).

Second, the results of this study demonstrated that job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction were positively correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.606). This is consistent with Kim et al. (2019) study, which found a positive relationship between leisure participation and job satisfaction among employed people with visual impairments. Also, several qualitative studies suggest the interrelationship between work and leisure among employed people with mobility impairments (Cook 2011, 2012; Cook and Shinew 2014). For example, participants in Cook’s (2011) study of employees with mobility impairments reported that leisure engagement enabled them to maintain good physical function and mental health, and helped their creativity and focus on work.

Furthermore, for Korean employees without disabilities, it was found that leisure satisfaction affects job satisfaction (Im and Park 2012; Lee and Paek 2010). Therefore, the results of the study provide empirical evidence that job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction are positively related to each other among Korean workers with and without disabilities.

Previous studies conducted in Western countries reported that job and leisure satisfaction were minimally-correlated for able-bodied people (London et al. 1977; Pearson 1998, 2008). Pearson (1998) found that job and leisure satisfaction were positively associated with psychological health but were low correlates when examining American male employees without disabilities. Pearson (2008) conducted a similar study on American female employees without disabilities and found that job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction were not significantly correlated. However, both predicted superior psychological health. Furthermore, London et al. (1977) found that job and leisure satisfaction were minimally-correlated, whereas both were significantly positively correlated with quality of life among employed Americans without disabilities. Thus, previous research provides evidence that job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction are relatively independent variables among employed people without disabilities in Western culture. Future research should explore cultural differences in relationships between job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction for employed people with disabilities.

Third, the results of this study indicated that employment status was significantly associated with life satisfaction. However, annual income did not. These findings are consistent with Park’s (2020) study showing that temporary employment has a negative influence on life satisfaction, while permanent employment has a positive influence on life satisfaction. The study also found that temporary employment, irrespective of wage raise, negatively affected life satisfaction. Based on these results, Park (2020) proposed that improving life satisfaction among employees with disabilities could be achieved through maintaining permanent employment and changing temporary employment to permanent employment.

Finally, the results of this study demonstrated that when both job and leisure were satisfied, individuals were 16.86 times happier than when they were dissatisfied with both their job and leisure. Furthermore, given they were satisfied with either their jobs or leisure activities, participants were 4.49 times happier than those who were dissatisfied with both their jobs and leisure activities. This study provides empirical evidence that employed people who were satisfied with their jobs and leisure activities are more satisfied with their lives than those who were satisfied with only their jobs. These findings suggest that positive leisure experiences for employed people with disabilities can help them increase their productivity at work and in other aspects of their lives.

Implications

This study is the first empirical research to examine how work and leisure influence the life satisfaction of employed people with physical disabilities. The results of this study have significant implications for leisure domains of employed people with physical disabilities. For employed people with physical disabilities, leisure engagement is an essential vehicle to deal with their mobility issues and job-related stress. Employers should introduce leisure programs during evenings and weekends, which can help facilitate a higher level of productivity and organizational loyalty for employed people with physical disabilities.

Limitations

This study used national-level data to identify the relationship between job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction as associated with life satisfaction among employed people with physical disabilities. However, these data were originally collected for a different purpose, so four major variables (i.e., job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and satisfaction with family relationships and satisfaction with friend relationships) were measured using a single self-report item. Consequently, future research should be conducted with multidimensional scales. In addition, more studies are needed for subgroup comparison of various ethnicities among Asian people with physical disabilities.

Furthermore, this study examined satisfaction with family relationships and satisfaction with friend relationships as confounding variables because they are important sources of social support. Unfortunately, our study provides limited information about social relationships with coworkers of employees with disabilities. Thus, future research on job, leisure, and life satisfaction of employed people with disabilities and social relationships should be conducted.

References

Aitchison, C. (2003). From leisure and disability to disability leisure: Developing data, definitions and discourses. Disability & Society, 18(7), 955–969.

Akkerman, A., Janssen, C. G., Kef, S., & Meininger, H. P. (2016). Job satisfaction of people with intellectual disabilities in integrated and sheltered employment: An exploration of the literature. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(3), 205–216.

Barišin, A., Benjak, T., & Vuletić, G. (2011). Health-related quality of life of women with disabilities in relation to their employment status. Croatian Medical Journal, 52(4), 550–556.

Brough, P., Timms, C., O'Driscoll, M. P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2014). Work–life balance: A longitudinal evaluation of a new measure across Australia and New Zealand workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(19), 2724–2744.

Byrne, U. (2005). Work-life balance: Why are we talking about it at all? Business Information Review, 22(1), 53–59.

Chamberlain, L. J., & Hodson, R. (2010). Toxic work environments: What helps and what hurts. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 455–477.

Cho, H. J., Park, J. K., & Park, L. E. (2011). An exploratory study on the factors influencing on life satisfaction of workers with physical disabilities. Korean Council of Physical, Multiple & Health Disabilities, 58(2), 203–227.

Choi, Y. R. (2017). A study of employment status change on life satisfaction of the disabled. Korean Journal of Care Management, 23, 79–95.

Chun, S., & Lee, Y. (2008). The experience of posttraumatic growth for people with spinal cord injury. Qualitative Health Research, 18(7), 877–890.

Cicerone, K. D., & Azulay, J. (2007). Perceived self-efficacy and life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(5), 257–266.

Cook, L.H. (2011). Disability, leisure, and work-life balance. unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.

Cook, L. (2012). “I’m not the typical handicapped person”: The significance of leisure for employed people with disabilities. Social Advocacy & Systems Change, 3(1), 22–37.

Cook, L. H., & Shinew, K. J. (2014). Leisure, work, and disability coping: “I mean, you always need that ‘in’group”. Leisure Sciences, 36(5), 420–438.

Cook, L. H., Foley, J. T., & Semeah, L. M. (2016). An exploratory study of inclusive worksite wellness: Considering employees with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 9(1), 100–107.

Coyle, C. P., Lesnik-Emas, S., & Kinney, W. B. (1994). Predicting life satisfaction among adults with spinal cord injuries. Rehabilitation Psychology, 39(2), 95–112.

Duvall, J., & Kaplan, R. (2014). Enhancing the well-being of veterans using extended group-based nature recreation experiences. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(5), 685–696.

EEOC. (2020). Disability discrimination. Available at https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/disability.cfm. Accessed Sept 2020.

Felce, D., & Perry, J. (1995). Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 16(1), 51–74.

Fontanive, V., Abegg, C., Tsakos, G., & Oliveira, M. (2013). The association between clinical oral health and general quality of life: a population‐based study of individuals aged 50–74 in Southern Brazil. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 41(2), 154–162.

Fuhrer, M. J., Rintala, D. H., Hart, K. A., Clearman, R., & Young, M. E. (1992). Relationship of life satisfaction to impairment, disability, and handicap among persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73(6), 552–557.

Giacobbi Jr., P. R., Stancil, M., Hardin, B., & Bryant, L. (2008). Physical activity and quality of life experienced by highly active individuals with physical disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 25(3), 189–207.

Gignac, M. A., Sutton, D., & Badley, E. M. (2007). Arthritis symptoms, the work environment, and the future: Measuring perceived job strain among employed persons with arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 57(5), 738–747.

Haar, J. M., Russo, M., Suñe, A., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2014). Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 361–373.

Hammell, K. W. (2007). Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord, 45(2), 124–139.

Hartman-Maeir, A., Soroker, N., Ring, H., Avni, N., & Katz, N. (2007). Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(7), 559–566.

Hassebrauck, M., & Fehr, B. (2002). Dimensions of relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 253–270.

Hay-Smith, E. J. C., Dickson, B., Nunnerley, J., & Anne Sinnott, K. (2013). “The final piece of the puzzle to fit in”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the return to employment in New Zealand after spinal cord injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(17), 1436–1446.

Holloway, I., Sofaer-Bennett, B., & Walker, J. (2007). The stigmatization of people with chronic back pain. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(18), 1456.

Horowitz, A., Reinhardt, J. P., Boerner, K., & Travis, L. A. (2003). The influence of health, social support quality and rehabilitation on depression among disabled elders. Aging & Mental Health, 7(5), 342–350.

Im, S. R., & Park, S. Y. (2012). Mediating effect of job satisfaction in the relationship between leisure satisfaction and organization commitment according to individual versus group leisure activity of the employees. Korean Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 25(1), 171–193.

Kalliath, T., & Brough, P. (2008). Work–life balance: A review of the meaning of the balance construct. Journal of Management & Organization, 14(3), 323–327.

Kaye, H. S., Jans, L. H., & Jones, E. C. (2011). Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21(4), 526–536.

Kim, K. I., Kim, K. J., & Park, D. H. (2010). The effects of regular physical activity on social-psychological and physiological factors in workers with disability. Journal of Adapted Physical Activity & Exercise, 18(1), 33–51.

Kim, B. K., Ha, Y. J., & Choi, S. S. (2014a). Longitudinal study on effects of psychological and environmental factors in relation to job satisfaction of wage earners with disabilities. Journal of Disability and Welfare, 26, 101–119.

Kim, M. H., Won, H. J., & Shin, K. L. (2014b). A search for meaning and direction of resting in contemporary leisure studies. Philosophy of Movement, 22(1), 155–171.

Kim, S. W., Lee, Y. H., Cho, J. D., Uy, H. B., Eom, M. S., & Oh, H. M. (2019). The mediator role of self-esteem in the pathways from job satisfaction and leisure activities to acceptance of disability in workers with visual impairment. Journal of Disability and Welfare, 43, 133–155.

Kinney, W. B., & Coyle, C. P. (1992). Predicting life satisfaction among adults with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 73(9), 863–869.

Kirchmeyer, C. (2000). Work–life initiatives: Greed or benevolence regarding workers’ time? In C. L. Cooper & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Trends in organisational behavior (Vol. 7, pp. 79–93). Chichester: Wiley.

Kleiber, D. A., Hutchinson, S. L., & Williams, R. (2002). Leisure as a resource in transcending negative life events: Self-protection, self-restoration, and personal transformation. Leisure Sciences, 24(2), 219–235.

Knecht, M., Wiese, B. S., & Freund, A. M. (2016). Going beyond work and family: A longitudinal study on the role of leisure in the work–life interplay. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(7), 1061–1077.

Kong, E., Hassan, Z., & Bandar, N. F. A. (2020). The mediating role of leisure satisfaction between work and family domain and work-life balance. Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development, 6(1), 44–66.

Kulkarni, M., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Socialization of people with disabilities in the workplace. Human Resource Management, 50(4), 521–540.

Kuykendall, L., Lei, X., Tay, L., Cheung, H. K., Kolze, M., Lindsey, A., et al. (2017). Subjective quality of leisure & worker well-being: Validating measures & testing theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 14–40.

Lee, Y. M., & Paek, S. K. (2010). The effect of leisure satisfaction on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Korean Academy of Organization &Management, 34(1), 25–62.

Lee, M. J., & Hwang, S. H. (2014). Happiness as the leisure time increases: An application of Easterlin paradox to leisure studies. Journal of Leisure and Recreation Studies, 38(2), 29–38.

London, M., Crandall, R., & Seals, G. W. (1977). The contribution of job and leisure satisfaction to quality of life. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(3), 328.

Loy, D. P., Dattilo, J., & Kleiber, D. A. (2003). Exploring the influence of leisure on adjustment: Development of the leisure and spinal cord injury adjustment model. Leisure Sciences, 25(2–3), 231–255.

Milevsky, I. M., Szuchman, L., & Milevsky, A. (2008). Transmission of religious beliefs in college students. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 11(4), 423–434.

Naude, R., Kruger, S., & Saayman, M. (2012). Does leisure have an effect on employee's quality of work life? South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 34(2), 153–171.

Nimrod, G. (2007). Retirees’ leisure: Activities, benefits, and their contribution to life satisfaction. Leisure Studies, 26(1), 65–80.

Pagan, R. (2017). Impact of working time mismatch on job satisfaction: Evidence for German workers with disabilities. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(1), 125–149.

Park, M. J. (2020). A longitudinal study of status changes of regular work and wage on life satisfaction with wage worker with disabilities. Korean Journal Care Management, 34, 5–21.

Park, K. P., & Kim, D. C. (2015). Impact of job satisfaction on quality of life for the disabled: Focusing on the moderation effect of job suitability and discrimination experience due to disability. Disability & Employment, 25(4), 57–88.

Park, Y., Seo, D. G., Park, J., Bettini, E., & Smith, J. (2016). Predictors of job satisfaction among individuals with disabilities: An analysis of South Korea's National Survey of employment for the disabled. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 53, 198–212.

Patterson, I., & Pegg, S. (2009). Serious leisure and people with intellectual disabilities: Benefits and opportunities. Leisure Studies, 28(4), 387–402.

Pearson, Q. M. (1998). Job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and psychological health. The Career Development Quarterly, 46(4), 416–426.

Pearson, Q. M. (2008). Role overload, job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and psychological health among employed women. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(1), 57–63.

Petrovski, P., & Gleeson, G. (1997). The relationship between job satisfaction and psychological health in people with an intellectual disability in competitive employment. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 22(3), 199–211.

Post, M. W., Van, A. D., Van, F. A., & Schrijvers, A. J. (1998). Life satisfaction of persons with spinal cord injury compared to a population group. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 30(1), 23–30.

Saunders, S. L., & Nedelec, B. (2014). What work means to people with work disability: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(1), 100–110.

Schönherr, M. C., Groothoff, J. W., Mulder, G. A., & Eisma, W. H. (2005). Participation and satisfaction after spinal cord injury: Results of a vocational and leisure outcome study. Spinal Cord, 43(4), 241–248.

Schulz, R., & Decker, S. (1985). Long-term adjustment to physical disability: The role of social support, perceived control, and self-blame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(5), 1162–1172.

Sirgy, M. J., & Lee, D. J. (2018). Work-life balance: An integrative review. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13(1), 229–254.

Snir, R., & Harpaz, I. (2002). Work-leisure relations: Leisure orientation and the meaning of work. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(2), 178–203.

Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific Sociological Review, 25(2), 251–272.

Tasiemski, T., Kennedy, P., Gardner, B. P., & Taylor, N. (2005). The association of sports and physical recreation with life satisfaction in a community sample of people with spinal cord injuries. NeuroRehabilitation, 20(4), 253–265.

Tough, H., Siegrist, J., & Fekete, C. (2017). Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 1–18.

Uppal, S. (2005). Disability, workplace characteristics and job satisfaction. International Journal of Manpower, 26(4), 336–349.

Vestling, M., Tufvesson, B., & Iwarsson, S. (2003). Indicators for return to work after stroke and the importance of work for subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 35(3), 127–131.

Villotti, P., Corbiere, M., Dewa, C. S., Fraccaroli, F., Sultan-Taieb, H., Zaniboni, S., & Lecomte, T. (2018). A serial mediation model of workplace social support on work productivity: The role of self-stigma and job tenure self-efficacy in people with severe mental disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(26), 3113–3119.

Watkins, C. E., & Subich, L. M. (1995). Annual review, 1992–1994: Career development, reciprocal work/non-work interaction, and women's workforce participation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47(2), 109–163.

Wu, H. C. (2008). Predicting subjective quality of life in workers with severe psychiatric disabilities. Community Mental Health Journal, 44(2), 135–146.

Zheng, C., Molineux, J., Mirshekary, S., & Scarparo, S. (2015). Developing individual and organisational work-life balance strategies to improve employee health and wellbeing. Employee Relations, 37(3), 354–379.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M., Jasper, A.D., Lee, J. et al. Work, Leisure, and Life Satisfaction for Employees with Physical Disabilities in South Korea. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 469–487 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09893-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09893-4