Abstract

Entrepreneurial ecosystems research has largely focused on the profile of a handful of successful locations. This has prevented a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that shape entrepreneurial activity across the geographical space. Our goals in this research are (1) to identify the critical dimensions of entrepreneurial ecosystems, and (2) to assess whether successful ecosystems rely on heterogeneous configurations. Through fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis, we address this issue with data from the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Findings generate a typological hierarchy of attributes, where the range of critical dimensions seems to be much more restricted than previously argued, and alternative configurations appear to lead to similar outcomes. A first pivotal path toward establishing a thriving ecosystem is fundamentally based on the conditions of the knowledge Infrastructure. A second approach combines elements of the socioeconomic system with the knowledge environment. Although some elements are ubiquitous, contributing attributes differ across distinct configurations, suggesting some level of heterogeneity in the dominant dimensions of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Such evidence contributes to the debate on entrepreneurial ecosystems’ dimensions and elements, offering exploratory insights on alternative ways to promote an environment conducive to knowledge-intensive ventures.

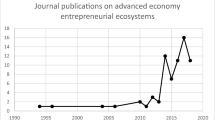

Source: Authors (based on research data)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While our analytical framework does not include an express mention to policy for local-level ecosystems, manifestations of institutional initiatives can be perceived in a distributed manner in most components of the model that are related both to the knowledge infrastructure and the socioeconomic system.

To complement this perspective, we plot cities in a map (Sect. 6) allowing to infer potential spillovers associated with EE.

This follows the notion that innovative entrepreneurial activity is not necessarily connected to newly founded firms (e.g., Spigel 2017; Henrekson and Sanandaji 2019; Kirzner 1997; Baumol 1996), but rather on the Schumpeterian tradition defining entrepreneurs as those who “exploit market opportunity through technical and/or organizational innovation” (Schumpeter 1965).

Ultimately, the definition of inputs and outputs will be arbitrary to some extent, as the relationships in ecosystems are complex and involve high degrees of endogeneity (Spigel 2017).

For both universities and habitats, as we deal with a pooled sample, there is the risk of a given university, incubator and/or science park springing up or closing down throughout the period. For these cases, our analysis dealt with the percentage of observed years in which the municipality had an active entrepreneurial habitat or research university.

The complete truth table is available from the authors upon request.

“A counterfactual case is a substantively relevant combination of causal conditions that nevertheless does not exist empirically” (Ragin 2008, p.9). Counterfactuals involve all possible combinations that could lead to an outcome to which data are unavailable or are redundant as an explanatory assertation. ‘Easy’ counterfactuals are those cases where available data exist, but are redundant as a causal explanation. ‘Difficult’ counterfactuals come from those cases that cannot be observed given the lack of available data.

It should be pointed out, however, that the statistical associations between research universities and other explanatory variables are moderate (Habitats and Tertiary Enrollment) or weak (Knowledge-Intensive Jobs, Diversity)—see "Appendix 3" for the detailed correlation matrix. Hence, deterministic perceptions on the role of these academic institutions as potential policy solutions to engender entrepreneurial ecosystems are not recommended.

References

Ács Z, Armington C (2004) Employment growth and entrepreneurial activity in cities. Reg Stud 38(8):911–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280938

Ács Z, Autio E, Szerb L (2014) National systems of entrepreneurship: measurement issues and policy implications. Res Policy 43(3):47–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016

Ács Z, Stam E, Audretsch D, O’Connor A (2017) The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus Econ 49(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9864-8

Agénor P (2015) Public capital, health persistence and poverty traps. J Econ 115(2):103–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-014-0418-0

Alvedalen J, Boschma R (2017) A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems: towards a future research agenda. Eur Plan Stud 25(6):887–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1299694

Alves AC, Fischer B, Vonortas NS, Queiroz S (2019) Configurations of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial ecosystems. Revista de Administração de Empresas 59(4):242–257. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020190403

Armington C, Ács ZJ (2002) The determinants of regional variation in new firm formation. Reg Stud 36(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400120099843

Asheim BT, Smith HL, Oughton C (2011) Regional innovation systems: theory, empirics and policy. Reg Stud 45(7):875–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.596701

Audretsch D, Belitski M (2017) Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: establishing the framework conditions. J Technol Transf 42(5):1030–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9473-8

Audretsch D, Feldman M (1996) R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. Am Econ Rev 86(3):630–640

Audretsch D, Link A (2019) The fountain of knowledge: an epistemological perspective on the growth of U.S. SBIR-funded firms. Int Entrep Manag J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00596-3

Audretsch DB, Heger D, Veith T (2015) Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 44(2):219–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9600-6

Audretsch D, Kuratko D, Link A (2016) Dynamic entrepreneurship and technology-based innovation. J Evol Econ 26(3):603–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-016-0458-4

Auerswald P, Dani L (2017) The adaptive life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems: the biotechnology cluster. Small Bus Econ 49(1):97–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9869-3

Auerswald P, Dani L (2018) Economic ecosystems. In: Clark G, Feldman M, Gertler M, Wojcik D (eds) The new oxford handbook of economic geography. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 245–268

Autio E, Kenney M, Mustar P, Siegel D, Wright M (2014) Entrepreneurial innovation: the importance of context. Res Policy 43(7):1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.01.015

Baglieri D, Baldi F, Tucci C (2018) University technology transfer office business models: one size does not fit all. Technovation 76–77:51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.05.003

Balland P, Jara-Figueroa C, Petralia S, Steijn M, Rigby D, Hidalgo C (2018) Complex economic activities concentrate in large cities [papers in evolutionary economic geography #18.29]. Utrecht Univ Urban Reg Res Centre. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3219155

Banks-Leite C, Ewers RM (2009) Ecosystem boundaries. Wiley, Chichester. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0021232

Baumol W (1996) Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive, and destructive. J Bus Ventur 11(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-x

Belderbos R, Sleuwaegen L, Somers D, and De Backer K (2016) Where to locate innovative activities in global value chains: does co-location matter? [Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers n. 30]. OECD. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/23074957

Bercovitz J, Feldman M (2006) Entrepreneurial universities and technology transfer: a conceptual framework for understanding knowledge-based economic development. J Technol Transf 31(1):175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-005-5029-z

Boschma R, Martin R (2010) The aims and scope of evolutionary economic geography. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography (PEEG) 1001, Utrecht University, Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Group Economic Geography, revised Jan 2010. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849806497.00007

Bosma NS, Schott T, Terjesen S, Penny K (2015) Global entrepreneurship monitor. Babson College, London Business School and Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA)

Bresnahan T, Gambardella A, Saxenian A (2001) Old economy inputs for new economy outcomes: cluster formation in the new Silicon Valleys. Ind Corp Change 10(4):835–860. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/10.4.835

Brown R, Mason C (2017) Looking inside the spiky bits: a critical review and conceptualization. Small Bus Econ 49(1):11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9865-7

Bruns K, Bosma N, Sanders M, Schramm M (2017) Searching for the existence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: a regional cross-section growth regression approach. Small Bus Econ 49(1):31–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9866-6

Cao Z, Shi X (2020) A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial ecosystems in advanced and emerging economies. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00326-y

Chatterji A, Glaeser E, Kerr W (2013) Clusters of entrepreneurship and innovation. [Working Paper 19013]. Nat Bureau Econ Res Work Paper Ser. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3386/w19013

Coduras A, Clemente JA, Ruiz J (2016) A novel application of fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis to GEM data. J Bus Res 69(4):1265–1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.090

Corrente S, Greco S, Nicotra M, Romano M, Schillaci C (2019) Evaluating and comparing entrepreneurial ecosystems using SMAA and SMAA-S. J Technol Transf 44(2):485–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9684-2

Crescenzi R, Rodríguez-Pose A (2012) An integrated framework for the comparative analysis of the territorial innovation dynamics of developed and emerging countries. J Econ Surv 26(3):517–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118427248.ch8

Crescenzi R, Rodríguez-Pose A (2017) The geography of innovation in China and India. Int J Urban Reg Res 41(6):1010–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12554

Crevoisier O (2004) The innovative milieus approach: toward a territorialized understanding of the economy? Econ Geogr 80(4):367–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2004.tb00243.x

Delgado M, Porter M, Stern S (2010) Clusters and entrepreneurship. J Econ Geogr 10(4):495–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq010

Di Gregorio D, Shane S (2003) Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Res Policy 32(2):209–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0048-7333(02)00097-5

Doeringer P, Evans-Klock C, Terkla D (2004) What attracts high performance factories? Management culture and regional advantage. Reg Sci Urban Econ 34(5):591–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2003.08.001

Dorfman N (1983) Route 128: the development of a regional high technology economy. Res Policy 12(6):299–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(83)90009-4

Duranton G, Puga D (2002) Diversity and specialisation in cities: Why, where and when does it matter? In: McCann P (ed) Industrial location economics. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 151–186

Etzkowitz H (2019) Is silicon valley a global model or unique anomaly? Ind Higher Educ 33(2):83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422218817734

Feld B (2012) Startup Communities: building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. Wiley, Hoboken. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119204459

Feldman M (2005) The Locational dynamics of the Us biotech industry: knowledge externalities and the anchor hypothesis. In: Quadrio Curzio A, Fortis M (eds) Research and technological innovation. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, pp 201–224

Feldman M, Lendel I (2011) The emerging industry puzzle optics unplugged. In: Bathelt H, Feldman MP, Kogler DF (eds) Beyond territory dynamic geographies of knowledge creation diffusion and innovation. Routledge, London and New York, pp 107–148

Fini R, Grimaldi R, Santoni S, Sobrero M (2011) Complements or substitutes? The role of universities and local context in supporting the creation of academic spin-offs. Res Policy 40(8):1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.013

Fischer M, Nijkamp P (2018) The nexus of entrepreneurship and regional development. [Working Papers in Regional Science #2018/05]. WU Vienna University of Economics and Business. http://epub.wu.ac.at/id/eprint/6362

Fischer B, Queiroz S, Vonortas N (2018a) On the location of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship in developing countries: lessons from São Paulo, Brazil. Entrep Reg Develop 30(5–6):612–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1438523

Fischer B, Schaeffer P, Silveira J (2018b) Universities’ gravitational effects on the location of knowledge-intensive investments in Brazil. Sci Pub Policy 45(5):692–707. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy002

Fischer B, Schaeffer P, Queiroz S (2019) High-growth entrepreneurship in a developing country: regional systems or stochastic process? Acc Manag 64(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.22201/fca.24488410e.2019.1816

Fitjar R, Rodríguez-Pose A (2011) Innovating in the periphery: firms, values and innovation in Southwest Norway. Eur Plan Stud 19(4):555–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.548467

Florida R (2002) The rise of the creative class. Basic Books, New York

Florida R (2005) The world is spiky: globalization has changed the economic playing field, but hasn’t leveled it. Atl Mon 296(3):48

Florida R, Mellander C (2016) Rise of the startup city: the changing geography of the venture capital financed innovation. Calif Manag Rev 59(1):14–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125616683952

Fotopoulos G (2014) On the spatial stickiness of UK new firm formation rates. J Econ Geogr 14(3):651–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbt011

Fritsch M (2019) The regional emergence of innovative start-ups: a research agenda. In: Audretsch D, Lehmann E, Link A (eds) A research agenda for entrepreneurship and innovation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Fritsch M, Sorgner A, Wyrwich M, Zazdravnykh E (2019) Historical shocks and persistence of economic activity: evidence on self-employment from a unique natural experiment. Reg Stud 53(6):790–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1492112

Galope R (2014) What types of start-ups receive funding from the small business innovation research (SBIR) program? Evidence from the Kauffman firm survey. J Technol Manag Innov 9(2):17–28. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-27242014000200002

Gilbert B, Audretsch D, McDougall P (2004) The emergence of entrepreneurship policy. Small Bus Econ 22(3–4):313–323. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:sbej.0000022235.10739.a8

Giner JM, Santa-María MJ, Fuster A (2016) High-growth firms: does location matter? Int Entrep Manag J 13(1):75–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0392-9

Glaeser E (2011) Triumph of the city: how our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier. Penguin Books, New York

Godley A, Morawetz N, Soga L (2019) The complementarity perspective to the entrepreneurial ecosystem taxonomy. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00197-y

Greckhamer T, Misangyi VF, Fiss PC (2013) The two QCAs: from a small-N to a large-N set theoretic approach. In: Fiss P, Cambré B, Marx A (eds) Configurational theory and methods in organizational research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 49–75

Hayter C, Nelson A, Zayed S, O’Connor A (2018) Conceptualizing academic entrepreneurship ecosystems: a review, analysis and extension of the literature. J Technol Transf 43(4):1039–1082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9657-5

Henrekson M, Sanandaji T (2019) Measuring entrepreneurship: do established metrics capture Schumpeterian entrepreneurship? Entrep Theory Pract. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719844500

Hernández C, González D (2017) Study of the start-up ecosystem in Lima, Peru: analysis of interorganizational networks. J Technol Manag Innov 12(1):71–83. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-27242017000100008

Hidalgo C et al (2018) The principle of relatedness. In: Morales A, Gershenson C, Braha D, Minai A, Bar-Yam Y (eds) Unifying themes in complex systems IX. ICCS 2018. Springer proceedings in complexity. Springer, Cham

Howell S (2017) Financing innovation: evidence from R & D grants. Am Econo Rev 107(4):1136–1164. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150808

Isaksen A, Trippl M (2017) Innovation in space: the mosaic of regional innovation patterns. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 33(1):122–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grw035

Isenberg D (2010) How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harv Bus Rev 88(6):40–51

Jacobides M, Cennamo C, Gawer A (2018) Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strateg Manag J 39(8):2255–2276. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2904

Kantis, H. (2018). Mature and developing ecosystems: a comparative analysis from an evolutionary perspective. [Working Paper #1/2018]. Prodem. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/88453

Keeble D, Walker S (2006) New firms, small firms and dead firms: spatial patterns and determinants in the United Kingdom. Reg Stud 28(4):411–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409412331348366

Kirzner I (1997) Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: an Austrian approach. J Econ Lit 35:60–85

Lerner J (2002) When bureaucrats meet entrepreneurs: the design of effective public venture capital programmes. Econ J 112(477):F73–F84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00684

Link A, Sarala R (2019) Advancing conceptualization of university entrepreneurship ecosystems: the role of knowledge-based entrepreneurial firms. Int Small Bus J 37(3):289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618821720

Malecki EJ (1997a) Entrepreneurs, networks, and economic development. Adv Entrep Firm Emerg Growth 3:57–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1074-754020180000020010

Malecki EJ (1997b) Technology and Economic development. Addison Wesley Longman, Harlow

Malecki EJ (2018) Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geopgrf Compass 12(3):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12359

Malerba F, McKelvey M (2018) Knowledge-intensive innovative entrepreneurship integrating Schumpeter, evolutionary economics, and innovation systems. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0060-2

Marshall A (1920) Principles of economics. MacMillan, London

Mason C, Brown R (2014) Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Paris Final Rep OECD 30:77–102

Mazzarol T (2014) Growing and sustaining entrepreneurial ecosystems: what they are and the role of government policy. [White Paper 01–2014]. Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand Ltd

Meijers E, Burger M (2017) Stretching the concept of ‘borrowed size.’ Urban Stud 54(1):269–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015597642

Mittelstaedt JD, Ward WA, Nowlin E (2006) Location, industrial concentration and the propensity of small US firms to export—entrepreneurship in the international marketplace. Int Mark Rev 23(5):486–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330610703418

Motoyama Y, Danley B (2012) An analysis of the geography of entrepreneurship: understanding the geographic trends of Inc. 500 companies over thirty years at the State and Metropolitan levels. [Report] Kauffman Foundation. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2145480

Neto J, Farias Filho J, Quelhas O (2014) Raising financial resources for small and medium enterprises: a multiple case study with Brazilian venture capital funds in the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Int J Innov Sustain Develop 8(1):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijisd.2014.059223

Nicotra M, Romano M, Giudice M, Schillaci C (2018) The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: a measurement framework. J Technol Transf 43(3):640–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9628-2

Pan F, Yang B (2019) Financial development and the geographies of startup cities: evidence from China. Small Bus Econ 52(3):743–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9983-2

Porter ME (1998) Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, Boston

Qian H (2018) Knowledge-based regional economic development: a synthetic review of knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Econ Develop Quart 32(2):163–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242418760981

Qian H, Haynes K (2014) Beyond innovation: the small business innovation research program as entrepreneurship policy. J Technol Transf 39(4):524–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9323-x

Radosevic S, Yoruk E (2013) Entrepreneurial propensity of innovation systems: theory, methodology and evidence. Res Policy 42(5):1015–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.01.011

Ragin C (2000) Fuzzy-set social science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ragin C (2006) Set relations in social research: evaluating their consistency and coverage. Polit Anal 14(3):291–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj019

Ragin C (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226702797.001.0001

Rasmussen E, Moen Ø, Gulbrandsen M (2006) Initiatives to promote commercialization of university knowledge. Technovation 26(4):518–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.11.005

Rice MP, Habbershon TG (2007) Introduction. In: Rice MP, Habbershon TG (eds) Entrepreneurship: the engine of growth. Praeger, Westport, CT

Roundy PT, Bradshaw M, Brockman BK (2018) The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: a complex adaptive systems approach. J Bus Res 86:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.032

Salles-Filho S, Bonacelli M, Carneiro A, Castro P, Santos F (2011) Evaluation of ST & I programs: a methodological approach to the brazilian small business program and some comparisons with the SBIR program. Res Eval 20(2):157–169. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211x12941371876184

Salles-Filho S, Fischer B, Zeitoum C, Feitosa P, Colugnati F (2019) Non-traditional indicators for the evaluation of SBIR-like programs: Evidence from Brazil. In: Proceedings of 17th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, September 2–5, Rome

Saxenian A (1994) Regional advantage: culture and competition in silicon valley and route 128. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Scherngell T (2013) The geography of networks and R & D collaborations. Springer, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02699-2

Schneider CQ, Wagemann C (2012) Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: a guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139004244.001

Schumpeter JA (1965) Economic theory and entrepreneurial history. In: Aitken HG (ed) Explorations in enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Spigel B (2017) The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep Theory Pract 41(1):49–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

Stam, E. (2009). Entrepreneurship, evolution and geography. [Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography]. Utrecht University—Urban and Regional Research Centre. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849806497.00014

Stam E, Spigel B (2016) Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. [Discussion Paper Series n. 16–13]. Utrecht University—Utrecht School of Economics

Stam E, van de Ven A (2019) Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00270-6

Stam E, Romme AGL, Roso M, van den Toren JP, van der Starre BT (2016) Knowledge triangles in the Netherlands: an entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. OECD, Paris

Sternberg R, Bloh J, Coduras A (2019) A new framework to measure entrepreneurial ecosystems at the regional level. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2018-0014

Storper M (1995) The resurgence of regional economies, ten years later the region as a nexus of untraded interdependencies. Eur Urban Reg Stud 2(3):191–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649500200301

Subrahmanya M (2017) How did Bangalore emerge as a global hub of tech start-ups in India? Entrepreneurial ecosystem—evolution, structure and role. J Develop Entrep 22(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1084946717500066

Tiffin S, Jimenez G (2006) Design and test of an index to measure the capability of cities in Latin America to create knowledge-based enterprises. J Technol Transf 31(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-005-5013-7

Van der Vlist A, Gerking S, Folmer H (2004) What determines the success of states in attracting SBIR awards? Econ Develop Quart 18(1):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242403258154

Vedula S, Fitza M (2019) Regional recipes: a configurational analysis of the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem for US venture capital-backed startups. Strateg Sci 4(1):4–24. https://doi.org/10.1287/stsc.2019.0076

Zahra SA, Wright M, Abdelgawad SG (2014) Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. Int Small Bus J 32(5):479–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613519807

Zou Y, Zhao W (2014) Anatomy of Tsinghua University Science Park in China: institutional evolution and assessment. J Technol Transf 39(5):663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-013-9314-y

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) in connection to the São Paulo Excellence Chair “Innovation Systems, Strategy and Policy” (InSySPo) at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) (Grant 2013/50524-6). Fischer also acknowledges Grant n. 2016/17801-4. Vonortas acknowledges the infrastructural support by UNICAMP’s Department of Science and Technology Policy and by the Institute for International Science and Technology Policy at the George Washington University. Fischer and Vonortas also acknowledge support from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics within the framework of the subsidy to the HSE by the Russian Academic Excellence Project ‘5–100’. None of these organizations is responsible for the contents of this paper. Valuable contributions from the Editor, Martin Andersson, and three anonymous reviewers were essential for this article. Remaining mistakes and misconceptions are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table

6.

Appendix 2: Frame of reference for knowledge-intensive activities (NACE Rev. 2)

Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products (20), Manufacture of rubber and plastic products (22), Manufacture of computer, electronic and optical products (26), Manufacture of motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers (29), Repair and installation of machinery and equipment (33), Computer programming, consultancy and related activities (62), Information service activities (63), Activities auxiliary to financial services and insurance activities (66), Legal and accounting activities (69), Activities of head offices; management consultancy activities (70), Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis (71), Scientific research and development (72), Advertising and market research (73), Other professional, scientific and technical activities (74).

Appendix 3

See Table

7.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cherubini Alves, A., Fischer, B.B. & Vonortas, N.S. Ecosystems of entrepreneurship: configurations and critical dimensions. Ann Reg Sci 67, 73–106 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01041-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01041-y