Abstract

Circular photocurrents (CPC), namely circular photogalvanic (CPGE) and photon drag effects, have recently been reported both in monolayer and multilayer transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) phototransistors. However, the underlying physics for the emergence of these effects are not yet fully understood. In particular, the emergence of CPGE is not compatible with the D3h crystal symmetry of two-dimensional TMDs, and should only be possible if the symmetry of the electronic states is reduced by influences such as an external electric field or mechanical strain. Schottky contacts, nearly ubiquitous in TMD-based transistors, can provide the high electric fields causing a symmetry breaking in the devices. Here, we investigate the effect of these Schottky contacts on the CPC by characterizing the helicity-dependent photoresponse of monolayer MoSe2 devices both with direct metal-MoSe2 Schottky contacts and with h-BN tunnel barriers at the contacts. We find that, when Schottky barriers are present in the device, additional contributions to CPC become allowed, resulting in emergence of CPC for illumination at normal incidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) offer a privileged material platform for the realization of ultrathin and efficient optoelectronics1,2. Their strong optical absorption, fast optoelectronic response, and high power conversion efficiencies, combined with functional properties such as flexibility, transparency, or self-powering make these materials highly promising for the development of optoelectronic devices3,4,5,6,7.

A particularly interesting feature of 2D-TMDs is the coupling between their spin and valley degrees of freedom8. In these materials, the optical bandgap is located at two non-equivalent valleys in the reciprocal space, usually labeled as K and K’, presenting different optical selection rules and opposite spin–orbit splitting both in the valence band and in the conduction band. In consequence, upon band-edge optical excitation with circularly polarized light, the spin and valley degrees of freedom of the optically excited electrons can be controlled by appropriately selecting the illumination wavelength and helicity9. It was recently shown that when a monolayer TMD (1L-TMD) is illuminated at an oblique angle with respect to the crystal plane, a helicity-dependent photocurrent (circular photocurrent, CPC) emerges. This effect has been attributed to circular photogalvanic (CPGE) and photon drag (CPDE) effects10,11,12 and opens exciting possibilities for the realization of 2D self-powered optoelectronic and opto-spintronic devices.

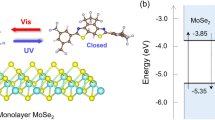

The physical origin of CPCs in 1L-TMDs is still far from understood. In particular, the emergence of CPGE requires a low crystal symmetry not compatible with the D3h symmetry found in pristine 1L-TMDs. Therefore, it requires an external agent – such as mechanical strain or a strong external electric field – to reduce the crystal symmetry to, at most, a single mirror-plane symmetry11. One possible agent that can cause this symmetry breaking is the strong electric field that emerges in Schottky contacts to 1L-TMDs13 when an external bias is applied. In a recent work11 we studied CPC in a hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) encapsulated 1L-MoSe2 phototransistor. There, the Schottky barriers were expected to be suppressed, or at least largely reduced, by the presence of bilayer h-BN tunnel barriers between the metallic contacts and the 1L-MoSe2 channel14,15. Here, to clarify the role of Schottky barriers we investigate helicity-dependent photocurrents in 1L-MoSe2 devices both with direct metal/MoSe2 contacts and with metal/h-BN/MoSe2 tunnel contacts. In both cases, we observe a CPC that is maximized for an illumination wavelength λ = 790 nm (matching the room-temperature A-exciton resonance of 1L-MoSe2), increases with the gate voltage, and depends nontrivially on the source–drain voltage and the light incidence angle. However, for the direct metal contact geometry, a nonzero drain–source voltage applied between the sensing contacts is needed to obtain a measurable photocurrent, while for the device with h-BN tunnel barriers a nonzero CPC can be clearly observed even at zero drain–source voltage. We find that for devices with direct metal/MoSe2 contacts where asymmetric Schottky barriers are expected to be present, a nonzero CPC emerges even for light incident normal to the crystal plane. This is contrary to the case of the device with h-BN tunnel barriers. Our results thus confirm that the presence of strong, anisotropic electric fields near the direct metal/MoSe2 contacts reduces the symmetry of the MoSe2 channel, leading to the emergence of additional contributions to the CPC, not present in devices with tunnel h-BN contacts.

The contact-dependent contributions to CPC observed here could also be present in earlier reported measurements attributed to the valley-hall effect16 (VHE) and to a Berry-curvature-induced circular photogalvanic effect10. These additional contributions to the observed CPC could be distinguished by their characteristic dependence on the illumination angle. Our results thus demonstrate the crucial importance of angle-resolved measurements for an adequate characterization of helicity-dependent optoelectronic effects in 2D systems.

Results

Device characterization and measurement geometry

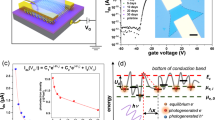

Figure 1a shows a sketch of the device with direct metal/1L-MoSe2 contacts (a microscope image of the actual device can be found in Supplementary Note 1). We first exfoliated and identified 1L-MoSe2 and multilayer h-BN flakes by standard micromechanical cleavage, and confirmed their flake thickness by atomic force microscopy (see Supplementary Note 1). Then, we used a dry, adhesive-free pick-up technique17 to fabricate the 1 L-MoSe2/h-BN heterostructure on a SiO2 (285 nm)/p-doped Si substrate. Finally, we fabricated Ti (5 nm)/Au (75 nm) electrodes on top of the structure by standard electron-beam lithography and metal evaporation. The contact geometry shown in Fig. 1 allows us to measure the optoelectronic response of the device in two perpendicular directions. We use a similar fabrication process and contact geometry for the device with h-BN tunnel barriers, as detailed in the Methods section. In that case, the 1L-MoSe2 channel is fully encapsulated between a thick h-BN layer and a bilayer h-BN, and metallic electrodes are fabricated directly on top of the bilayer h-BN.

a Schematic of the device with direct metal / 1 L-MoSe2 contacts and measurement geometry. The optical excitation is achieved by exposing the entire device to a wavelength-tuneable laser source, hitting the sample at an oblique angle of incidence ϕ. The polarization and helicity of the light excitation is selected using a λ/4 waveplate. The bottom diagrams show a side view of the two possible device geometries, either with Ti/Au Schottky contacts fabricated directly on top of the 1L-MoSe2/hBN structure (left) or with a top bilayer hBN flake acting as tunnel barrier between the 1L-MoSe2 and the contacts (right). b Two-terminal transfer characteristic of the device for V12 = 10 V, showing a clear n-type behavior. The threshold gate voltage is found to be around Vgth = 40 V. Inset: I–V characteristic measured at Vg = 50 V. Arrows indicate scan direction. c Total current I12 along the device for V12 = 10 V and Vg = 50 V. When the light excitation (λ = 790 nm) is turned on, the total current along the device increases by IPC = 1.4 nA. d Photocurrent IPC (red circles) as a function of the waveplate rotary angle θ and fitting to Eq. 1 (black, solid line). The discontinuous lines represent the three separate contributions indicated in Eq. 1, I0 (black, dash-dotted line), L sin(4θ + δ) (blue, dashed line) and C sin(2θ) (green, dotted line).

For all the measurements described below, the devices were kept in vacuum and at room temperature. Figure 1b shows a two-terminal transfer characteristic of the non-encapsulated device, presenting a clear n-type behavior with a threshold gate voltage Vgth = 40 V. The device threshold voltage also presented a slow drift over long periods of time, changing by up to 10–15 V over a 24 h period. We attribute this slow drift to charging/discharging of local impurities at the SiO2 substrate.

The I–V characteristic (inset in Fig. 1b) is highly nonlinear, due to the presence of asymmetric Schottky barriers at the metal-MoSe2 contacts. The device with h-BN tunnel barriers also presents a nonlinear I–V characteristic, as shown in Supplementary Note 2 and discussed in detail in ref. 14.

For characterizing the device photoresponse, we uniformly illuminate the whole sample using a wavelength-tunable continuous wave (CW) laser source and measure the resulting photocurrent. Importantly for our measurements, we use collimated light for optical excitation, as opposed to focusing the light with a high numerical aperture microscope objective. This illumination geometry allows us to control precisely the light incidence angle ϕ. Figure 1c shows the registered source–drain current I12 when the laser source is turned on and off using a chopper for source–drain voltage V12 = 10 V, gate voltage Vg = 50 V, illumination wavelength λ = 790 nm, linear polarization, and light incidence angle ϕ = 30°. As shown in Fig. 1a, the illumination plane (highlighted in faint red in the figure) is fixed along the direction between contacts 3 and 4.

When the light is turned on, electrons in the MoSe2 valence band undergo an optical transition to the conduction band, either directly or by formation of excitons, which results in an increase in the conductivity (photoconductivity). Thus, the current flowing through the device increases by IPC. In the measurements discussed below, IPC is registered using a lock-in amplifier set at the frequency of the mechanical chopper.

In a 2D-TMD phototransistors, photoconductivity can emerge from two main coexisting mechanisms18,19,20,21,22,23: photoconductive effect, where light-induced formation of electron–hole pairs leads to an increased charge carrier density; and photovoltaic effect, where light-induced filling or depletion of localized states results in a shift of the Fermi energy. When the characteristic relaxation times for these localized states are very long, photovoltaic effects appear as photodoping, and the Fermi energy shift remains for a long time, or even permanently, after the optical excitation is turned off24.

To characterize the helicity-dependent photoresponse of our device we tune the polarization of the incident light by a λ/4 waveplate. Over a 360° waveplate rotation, the light is modulated twice between left and right circular polarization. Figure 1d shows the helicity-dependent photocurrent IPC as a function of the angle θ of the fast axis of the waveplate with respect to the polarization axis of the incoming laser. The resulting signal IPC(θ) can be phenomenologically described as

Here, I0, C, and L, respectively, account for the polarization-independent, helicity-dependent, and linear polarization-dependent components of IPC. Note that the helicity-dependent component C sin(2θ) must be zero for θ = 0 (waveplate fast axis aligned with incident polarization), which corresponds to the output bean being fully linearly polarized. In contrast, the linear polarization-dependent part L sin(4θ + δ) can in principle be maximal for any arbitrary angle, depending on the relative orientation of the incident light polarization and the device. Thus, a phase δ must be included in the equation. It is also worth remarking that Eq. 1 is purely phenomenological, and no assumption is made regarding the microscopic origin of the linear- and helicity-dependent components. In particular, C can include contributions from several effects, including CPGE and CPDE.

Spectral behavior of CPC

Figure 2 shows the spectral dependence of the polarization-independent (I0) and helicity-dependent (C) photocurrent components, measured in two-terminal configuration using contacts 1 and 2, with V12 = 10 V, Vg = 50 V, and ϕ = 30°. Both I0 and C are peaked around λ ≈ 790 nm, matching the wavelength of the 1 L-MoSe2 A-exciton resonance19,25,26. For off-resonance wavelengths shorter than 775 nm, C becomes strongly suppressed, even when I0 still remains large. This result is consistent with our earlier measurements in hBN-encapsulated devices11 and with recent optical measurements showing that light-induced valley population imbalance under off-resonance excitation is rapidly relaxed by intervalley scattering of high-energy excited carriers9,27. Therefore, resonant exciton absorption is necessary for efficient CPC generation. For excitation wavelengths longer than λ ≈ 825 nm only a small polarization-independent photocurrent is observed.

a Colormap of IPC as a function of the waveplate angle (x axis) and the excitation wavelength (left axis). The gray scale in the colormap represents IPC, and the solid lines (right axis) show individual IPC profiles at equispaced wavelengths between 720 and 840 nm. For clarity, the base level of these profiles has been shifted vertically in steps of 0.5 nA. b I0 (blue, right axis) and C (red, left axis) parameters, obtained from least-square fitting of Eq. 1 to the data shown in a, as a function of the excitation wavelength.

Dependence of CPC on the gate voltage

Next, we investigate the effect of the gate voltage on the photocurrent. We apply gate voltages between Vg = −50 V and +50 V while keeping a constant drain–source voltageV12 = 10 V and illuminating the sample at λ = 790 nm and ϕ = 30°. Figure 3a shows the registered photocurrent for the device with direct metal/MoSe2 contacts as a function of the incident light polarization. I0, C, and L can be extracted from fittings to Eq. 1 as described above. Figure 3b shows I0 and C as a function of the gate voltage. Both for I0 and C, a nonzero signal can only be observed at gate voltages near to or above Vth. A similar gate dependence of photoconductivity has been earlier observed in TMD phototransistors18,28, and indicates that the observed photoconductivity originates mainly from the photovoltaic effect mentioned above. Thus, the effect of the gate voltage is simply to modulate the overall photoresponse of the device, but does not change the ratio between I0 and C. As shown in Fig. 3b, c, the described behavior is observed both for samples with direct metal/MoSe2 contacts and with hBN tunnel barriers. However, for the sample with tunnel contacts, a nonzero I0 and C can be observed even at Vg < Vth, indicating the presence of an additional contribution to photocurrent. We attribute this new contribution to an enhanced photoconductive effect in hBN-encapsulated samples18.

a Measured photocurrent IPC in the non-encapsulated device for different gate voltages Vg, from −10 V to 50 V, as a function of the λ/4 waveplate angle. The black solid lines are least-square fits of the experimental data to Eq. 1. b–c Vg dependence of the I0 (blue circles, right axis) and C (orange triangles, left axis) photocurrent components for the non-encapsulated (b) and hBN-encapsulated (c) devices. The insets in pannels b and c show C as a function of I0 in logarithmic scale.

CPC and illumination angle of incidence

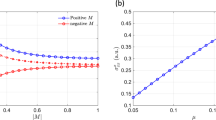

Figure 4a shows the measured photocurrent for λ = 790 nm, V12 = 10 V, and Vg = 50 V as a function of the waveplate angle for different illumination angles. From these measurements we extract the angle dependence of the helicity-dependent photocurrent, C, shown in Fig. 4b. The dependence of CPC on the illumination angle allows us to extract information on the underlying physical mechanism.

a Photocurrent IPC for V12 = 10 V and Vg = 50 V as a function of the waveplate angle for different illumination angles. Dots indicate experimental data. Solid lines are fittings to Eq. 1. b Dependence of C on the illumination angle, extracted from the fittings shown in (a). The dotted line is a parabolic fitting of the experimental data, shown as a guide to the eye.

As we discussed in ref. 11, CPGE cannot occur in a material with D3h symmetry, such as pristine 1L-MoSe2, while CPDE can only give contributions proportional to sin(2ϕ), which are odd upon inversion of the illumination angle ϕ and should cancel out for illumination normal to the crystal plane. For the device with direct metal/MoSe2 contacts studied here we find that C does not present even or odd parity upon inversion of the illumination angle. Furthermore, a nonzero helicity-dependent signal is observed even for normal-incidence illumination. This is in strong contrast with our results in h-BN encapsulated devices (see Supplementary Note 2 and ref. 11). For these devices, a nonzero angle of incidence is needed to generate a measurable CPC. Simple symmetry arguments can be used to show that a nonzero CPC signal at ϕ = 0° can only appear if the symmetry of the crystal is reduced to at most a single mirror-plane symmetry11. Thus, our results establish that the presence of non-equivalent Schottky barriers in the vicinity of the metallic contacts results in a largely reduced symmetry of the electronic states, allowing for additional contributions to the CPC. In fact, as shown in Supplementary Note 3, we observe that the overall strength and angle dependence of the CPC varies from one set of contacts to another, further suggesting that this effect is largely affected by the local geometry near the electrodes.

Effect of the drain–source voltage on CPC

Finally, we evaluate the dependence of the CPC on the drain–source voltage. As mentioned above, for the sample without h-BN tunnel barriers a nonzero bias voltage needs to be applied in order to observe nonzero C and L photocurrent components. This is again in contrast with our results for h-BN encapsulated devices (see Supplementary Note 2 and ref. 11), where a clear helicity-dependent photocurrent appears even in short-circuit configuration.

When V12 is swept, both C and L increase with the absolute value of Vds. However, the sign and amplitude of C depend on the angle of incidence in a nontrivial way. We also observe that C and L are largely dependent on the selected set of source–drain contacts for a fixed angle of incidence (see Supplementary Note 3). Figure 5 shows the dependence of C and L on the drain–source voltage V12 for two different angles of incidence (ϕ = +50° and ϕ = +50°). For +50° a nonzero helicity-dependent photocurrent C is clearly observed for positive drain source voltages V12, increasing monotonically with the applied voltage (see Fig. 5c). For negative voltages a smaller but measurable C is observed. Intriguingly, the sign of C is preserved when changing the sign of the drain–source voltage. However, when the illumination angle is inverted from 50° to −50° the sign of C flips from positive to negative, and a large signal is only observed for negative V12 (Fig. 5c). It is worth noting that the behavior described here is only valid for a specific set of contacts in the device and changes in a nontrivial way with the angle of incidence. Vds-dependent measurements for additional contacts and illumination angles can be found in Supplementary Note 3. The fact that C and L modulate differently with the drain–source voltage for different sets of contacts is consistent with our hypothesis, i.e., that the presence of nonhomogeneous Schottky barriers alters the symmetry of electronic states and thus enables additional contributions to the CPC, largely affecting the total measured CPC signal.

a, b Photocurrent IPC as a function of the waveplate angle for different drain–source voltages V12 between −10 V (blue) and +10 V (red), for a light incidence angles ϕ = +50° (a) and ϕ = −50° (b). Dots indicate experimental data. Solid lines are fittings to Eq. 1. c, d Dependence of C (c) and L (d) on the drain–source voltage, extracted from the fittings shown in (a) and (b).

Discussion

In a seminal theory work29, Moore and Orenstein showed that the presence of a nonzero Berry curvature in a 2D system can lead to the emergence of CPGE under illumination normal to the crystal plane. Further, they showed that the resulting CPGE has even symmetry upon inversion of the angle of incidence, changing proportionally to cos(ϕ). While earlier experimental attempts have aimed to detect this phenomenon in 2D TMDs10,11, the angular dependence observed in these works is not compatible with a Berry curvature-induced CPGE. In particular, a nonzero CPC was only observed for oblique illumination. In the light of our results, the device with direct metal–semiconductor yields a CPC that does not vanish for ϕ = 0° and contains both even and odd components upon inversion of the illumination angle. While the symmetry of this CPC is compatible with contributions from Berry curvature-induced CPGE, the observed signal could also be explained by the emergence of helicity-dependent photovoltaic effects near the metal–MoSe2 interfaces.

As discussed in earlier literature11, a nonzero CPC under normal-incidence illumination such as the one shown here is only possible for a device with, at most, a single mirror-plane symmetry. Indeed, we observe that when an h-BN tunnel barrier is inserted between the contacts and the 2D channel, the CPC signal upon normal illumination disappears. This indicates that the presence of strong electric fields at the Schottky contacts plays an important role in reducing the symmetry of the MoSe2 channel, enabling additional contributions to CPC. The particularities of the electric field profile in the vicinity of a specific metal–semiconductor contact strongly influence the measured signal, resulting in the observed contact-dependent CPC.

Importantly, earlier measurements on helicity-dependent photoresponse carried out in 1 L-TMD devices with direct metal–semiconductor contacts could also show contributions caused by a symmetry reduction near the contacts. For example, for the valley-Hall effect16, N. Ubrig et al. recently showed that the helicity-dependent signal is strongly modified when the vicinity of the electrodes is exposed to light13, which could be caused by a contact-induced symmetry breaking. In light of our measurements, inserting few-layer h-BN as tunnel barrier between the semiconductor channel and the metallic contacts minimizes possible effects of Schottky barriers on the device photoresponse, granting access to the intrinsic properties of a 2D-TMD. In particular, for devices with h-BN tunnel barriers the CPGE cancels out for normal incidence, as expected from the crystal symmetry.

Our results also show that CPCs can be very largely and nontrivially modulated by the illumination angle, even for incidence angles as small as 10°. However, most reports on helicity-dependent optoelectronic measurements rely on high numerical aperture objectives to focus the laser beam onto a small area of the sample. While this method has the advantage of granting micrometer spatial resolution, it comes at the price of losing resolution on the illumination angle, as the measured photoresponse will be averaged over a broad range of angles. Thus, in order to obtain a complete microscopic understanding of the helicity-dependent optoelectronic response of 2D-TMD devices, spatially resolved experiments should be used in combination with angle-resolved measurements. We envision that the symmetry-breaking generated by Schottky contacts can also be used for engineering of CPC in 2D-TMD phototransistors, opening up possibilities to tuning the photoresponse for circularly polarized light at particular incident angles for angular-resolved photodetectors.

Methods

Fabrication of hBN-encapsulated devices

We mechanically exfoliate atomically thin layers of MoSe2 and h-BN from their bulk crystals on a SiO2 (300 nm)/doped Si substrate. The monolayer MoSe2 and bilayer h-BN are identified by their optical contrasts with respect to the substrate and their thickness is confirmed by atomic force microscopy. Using a polymer-based dry pick-up technique, we pick up the bilayer h-BN flake with a PC (poly(bisphenol A)carbonate) layer attached to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp. Then we use the same stamp to pick up the MoSe2 flake directly in contact with the h-BN surface and we transfer the whole stack onto a bulk h-BN crystal, exfoliated on a different SiO2/Si substrate. After the final transfer step, the PC layer is detached from the PDMS, remaining on top of the 2L-BN/MoSe2/bulk-BN stack, and must be dissolved using chloroform. To further clean the stack, we anneal the sample in Ar/H2 at 350 °C for 3 h.

Electrode fabrication

The same electrode fabrication process is followed for the two device geometries (with and without hBN tunnel barriers). First, we pattern the stacks by electron-beam lithography using PMMA (poly(methyl methacrylate)) as the e-beam resist. This is followed by e-beam evaporation of Ti(5 nm)/Au(75 nm) at 10−6 mbar and lift-off in acetone at 40 °C.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Furchi, M. M. et al. Device physics of van der Waals heterojunction solar cells. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 3 (2018).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 780–793 (2014).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013).

Furchi, M. M., Pospischil, A., Libisch, F., Burgdörfer, J. & Mueller, T. Photovoltaic effect in an electrically tunable Van der Waals heterojunction. Nano Lett. 14, 4785–4791 (2014).

Groenendijk, D. J. et al. Photovoltaic and photothermoelectric effect in a double-gated WSe2 device. Nano Lett. 14, 5846–5852 (2014).

Ansell, D. et al. Hybrid graphene plasmonic waveguide modulators. Nano Lett. 14, 2741–2746 (2014).

Konstantatos, G. & Sargent, E. H. Nanostructured materials for photon detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 391–400 (2010).

Xiao, D., Liu, G., Bin, Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS 2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Eginligil, M. et al. Dichroic spin-valley photocurrent in monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 6, 7636 (2015).

Quereda, J. et al. Symmetry regimes for circular photocurrents in monolayer MoSe2. Nat. Commun. 9, 3346 (2018).

Yuan, H. et al. Generation and electric control of spin–valley-coupled circular photogalvanic current in WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 851–857 (2014).

Ubrig, N. et al. Microscopic origin of the valley Hall effect in transition metal dichalcogenides revealed by wavelength dependent mapping. Nano Lett. 17, 5719–5725 (2017).

Ghiasi, T. S., Quereda, J. & van Wees, B. J. Bilayer h-BN barriers for tunneling contacts in fully-encapsulated monolayer MoSe2 field-effect transistors. 2D Mater. 6, 015002 (2019).

Pande, G. et al. Ultralow schottky barriers in h-BN encapsulated monolayer WSe2 tunnel field-effect transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c01025 (2020).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Zomer, P. J., Guimaraes, M. H. D., Brant, J. C., Tombros, N. & Van Wees, B. J. Fast pick up technique for high quality heterostructures of bilayer graphene and hexagonal boron nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 013101 (2014).

Furchi, M. M., Polyushkin, D. K., Pospischil, A. & Mueller, T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 14, 22 (2014).

Quereda, J., Ghiasi, T. S., van Zwol, F. A., van der Wal, C. H. & van Wees, B. J. Observation of bright and dark exciton transitions in monolayer MoSe2 by photocurrent spectroscopy. 2D Mater. 5, 015004 (2018).

Miller, B., Parzinger, E., Vernickel, A., Holleitner, A. W. & Wurstbauer, U. Photogating of mono- and few-layer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 1–5 (2015).

Island, J. O., Blanter, S. I., Buscema, M., Van Der Zant, H. S. J. J. & Castellanos-Gomez, A. Gate controlled photocurrent generation mechanisms in high-gain In2Se3 phototransistors. Nano Lett. 15, 7853–7858 (2015).

Fang, H. & Hu, W. Photogating in low dimensional photodetectors. Adv. Sci. 4, 1700323 (2017).

Huang, H. et al. Highly sensitive visible to infrared MoTe2 photodetectors enhanced by the photogating effect. Nanotechnology 27, 445201 (2016).

Quereda, J., Ghiasi, T. S., Van Der Wal, C. H. & Van Wees, B. J. Semiconductor channel-mediated photodoping in h-BN encapsulated monolayer MoSe2 phototransistors. 2D Mater. 6, 025040 (2019).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1474 (2013).

Frisenda, R. et al. Micro-reflectance and transmittance spectroscopy: a versatile and powerful tool to characterize 2D materials. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 074002 (2017).

Kioseoglou, G. et al. Valley polarization and intervalley scattering in monolayer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, (2012).

Vaquero, D. et al. Excitons, trions and Rydberg states in monolayer MoS2 revealed by low temperature photocurrent spectroscopy. arXiv Prepr. arXiv2004.02526 (2020).

Moore, J. E. & Orenstein, J. Confinement-induced berry phase and helicity-dependent photocurrents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 026805 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Dutch Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter (FOM) as a part of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), FLAG-ERA (15FLAG01- 2), the European Unions Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreements No 696656 and 785219 (Graphene Flagship Core 2 and Core 3), NWO Start-Up (STU.019.014), NanoNed, the Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, and the Spinoza Prize awarded to BJ van Wees by NWO. J.Q acknowledges financial support from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación of Spain (Grants MAT2016-75955, PID2019-106820RB-C22, and RTI2018-097180-B-100) and the Junta de Castilla y León (Grant SA256P18), including funding by ERDF/FEDER. MHDG acknowledges financial support from NWO Veni (15093).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Q. and J.H. initiated the project. J.H. and T.G. performed the device fabrication. J.Q. and J.H. performed the measurements and analyzed the data, with M.H.D.G. assistance. B.J.v.W., C.H.v.W., and M.H.D.G. supervised the project. J.Q. wrote the manuscript with J.H. and M.H.D.G. assistance. All authors agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

PACS subject classification number: 73.50.pz (Electronic structure and electrical properties low-dimensional structures: Photoconduction and photovoltaic effects)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quereda, J., Hidding, J., Ghiasi, T.S. et al. The role of device asymmetries and Schottky barriers on the helicity-dependent photoresponse of 2D phototransistors. npj 2D Mater Appl 5, 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-00194-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-00194-w