Abstract

Prior research shows that highly religious consumers are more stable through times of uncertainty, in part due to religious support networks. However, several situations (e.g., pandemics, epidemics, natural disasters, mass shootings) represent unique changes where routine large gatherings are restricted due to uncertainty. In such situations, highly religious consumers may experience the greatest disruption to life, potentially resulting in stability-seeking consumption behaviors. Three studies test and confirm this relationship in the coronavirus pandemic context. Specifically, study 1 shows that priming awareness of restricted in-person religious gatherings increases consumption in comparison to a general religious prime or control condition. Study 2 confirms that consumers with higher (lower) levels of religiosity are the most (least) likely to increase consumption, and that situational concern and stability found through purchasing sequentially mediate this relationship. Study 3 provides practical implications revealing that stability-based messaging reduces consumption in comparison to standard social distancing messaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic has rapidly changed the lives of nearly everyone worldwide. The media clearly portrays consumers’ responses to this situation as desperation in trying to find products for purchase, many of which retailers are unable to keep stocked due to high demand (e.g., toilet paper, cleaning wipes, hand sanitizer) (Danziger 2020). The question arises among these challenges—why are consumers in such desperation for these products leading them to engage in purchasing significantly higher quantities of products than normal? And who are the consumers most likely to engage in such behaviors? These are both questions this research aims to answer with application to pandemics as well as other situations (e.g., epidemics, mass shootings, natural disasters) during times of great uncertainty.

Prior research suggests that the people who respond most calmly during times of uncertainty are those with strong support networks (Brashers et al. 2004). One of the most consistent forms of a supportive social network is religion, given that many religions have weekly (if not more frequent) religious gatherings (Stroope 2012). With over 80% of consumers worldwide being religious to some degree (PEW 2017), and religious values undergirding many consumption decisions (Minton and Kahle 2017), it is important to examine how religion may influence increased purchasing in response to times of uncertainty.

Given the strong support network that religion provides (Stroope 2012), it seems reasonable to presume that highly religious consumers should be less likely to participate in increased purchasing behaviors because such behaviors are likely the result of stability-seeking motives to make up for the uncertainties of life. However, national situations of uncertainty (e.g., pandemics, epidemics, mass shootings) represent unique situations that are different from the general uncertainties of life where consumers may be instructed, or even ordered through government mandate, to avoid contact with others. These guidelines or mandates likely lead to changes in the support consumers receive from their social networks.

Additionally, if highly religious consumers are the most likely to feel stability and support through consistent religious gatherings that allow for connection with their religious support network (Stroope 2012), then these highly religious consumers should also suffer the greatest disruption to their routines and social support in comparison to less or non-religious consumers who likely do not have the same level of consistent weekly connection with their social networks. As such, highly religious consumers may actually be the ones who are psychologically most affected during times of great uncertainty, resulting in stability-seeking consumption to make up for these changes and uncertainty.

We test this conceptual model of stability-seeking consumption behavior in three studies in the context of a pandemic. In doing so, we seek to accomplish three objectives: (1) identify how religiosity influences stability-seeking consumption behaviors, (2) test mediating explanatory mechanisms for this relationship, namely situational concern and life stability provided through purchase, and (3) prime religious constructs to isolate the effects as due to reduction in religious community interaction and less stability as a result of greater changes in weekly life for highly religious consumers.

2 Conceptual development

2.1 Stability-seeking consumption

While consumers typically consume to fill a want or need for a specific product or service, consumption can also occur when consumers are lacking a more general need in life and, therefore, consume to make up for this unfulfilled need (Gronmo 1988). Prior research shows that one such need that is sought through consumption is stability (Chakravarti and Janiszewski 2003; Vázquez-Casielles et al. 2007). Outside of marketing, the theory of subjective well-being homeostasis confirms humans’ striving for stability through behavioral adaptations in response to changes that create instability (Cummins 2016). Related to this, control theory describes that consumers use action-oriented problem solving skills in order to enhance well-being (Mirowsky and Ross 1990), which in the case of times of great uncertainty could be stability-seeking consumption behaviors. Together, prior research and theories suggest that consumers should strive for stability in times of uncertainty (such as a pandemic), and stability-focused consumption behaviors may be one way consumers try to achieve this sense of stability. To better understand the processes of stability-seeking consumption, we first must understand who is potentially participating in such consumption practices and why. The next section discusses religion as a driver behind stability-seeking consumption.

2.2 Religion and stability-seeking consumption

As mentioned earlier, religion serves as an important source of social support for many consumers worldwide (Bradley et al. 2020; Stroope 2012). Many religious groups have weekly, if not more frequent, religious services, which provide a consistent routine of social interaction and social support for religious individuals (Ammerman 2003). Additionally, research has shown that religious individuals have larger social networks compared to non-religious individuals (Ellison and George 1994). Following this logic, it would seem that consumers who are more religious would be less likely to be influenced during times of great uncertainty. Furthermore, these consumers may be less likely to engage in stability-seeking consumption behaviors because they live out religious values advocating against materialistic consumption and storing up physical goods as opposed to the pursuit of spiritual wealth (Schmidt et al. 2014).

However, large situations of uncertainty often involve limitations on direct in-person access to social support networks (McLafferty 2010; Sadique et al. 2007), thus potentially making more religious consumers feel greater instability during such uncertain times. While less or non-religious consumers are also likely faced with uncertainty and changes to weekly routines, these alterations are likely to be less so than for more religious consumers who have consistent and regimented weekly religious services as a cornerstone of their lives. As such, priming awareness of the lack of religious gatherings should produce increased stability-seeking consumption behaviors, thereby highlighting the mechanism of influence. We expect that a lack of religious gatherings triggers concepts in the mind related to a lack of social engagement for all consumers, regardless of their dispositional religiosity. Fitting with this, highly religious consumers are expected to most likely engage in stability-seeking consumption behaviors to regain a sense of stability during uncertain times. Thus:

-

H1: Priming awareness of the lack of religious gatherings, in comparison to a general religious prime or a control prime, will result in greater stability-seeking consumption behaviors for all consumers (religious or non-religious).

-

H2: Consumers with higher levels of religiosity are more likely to engage in stability-seeking consumption behaviors in comparison to consumers with lower levels of religiosity.

2.3 Mediating role of situational concern and stability through purchase

As previously mentioned, religious consumers are likely to experience more change in comparison to less or non-religious consumers given the inability to attend in-person weekly religious gatherings due to social interaction restrictions (McLafferty 2010; Sadique et al. 2007). High degrees of sudden change produce resistance and negative affective states (Bailey and Raelin 2015; Lamm and Gordon 2010). Additionally, prior research has shown that consumers with higher levels of religiosity may be more resistant to change because of a greater commitment to values such as tradition, conformity, and security (Choi 2010; Schwartz and Huismans 1995). Given this greater likelihood of change as well as resistance to change, we expect that consumers with higher (as opposed to lower) levels of religiosity will be more likely to feel concern.

According to the theory of subjective well-being homeostasis, situations of instability motivate actions to bring about a sense of homeostasis, or stability in one’s life (Cummins 2016). This motivation should, in turn, produce stability-seeking consumption strategies to reduce instability, which could be increasing purchasing behavior to provide a sense of stability. Additionally, fitting with this reasoning, messaging that aims to reestablish a sense of stability for consumers should aid in reducing stability-seeking consumption behaviors. Thus:

-

H3: Situational concern (H3a) and stability through purchase (H3b) sequentially mediate the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behaviors, such that consumers with higher levels of religiosity express greater situational concern, which leads to feeling more stability through purchase behavior, which ultimately increases consumption.

-

H4: Stability-based messaging will reduce stability-seeking consumption behaviors in comparison to non-stability-based messaging.

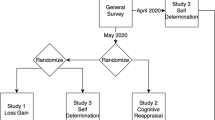

To test these hypotheses, we conduct three studies using the context of the coronavirus pandemic, a time of great uncertainty across the world. Study 1 primes awareness of restricted in-person religious gatherings as well as religion in general and tests these primes in comparison to a control condition to show the mechanism of influence (H1). Study 2 then tests the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behavior (H2) as well as tests for sequential mediation through situational concern and stability through purchase behavior (H3a and H3b). Study 3 then confirms the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behavior (H2) and, importantly, introduces practical implications of this work through government messaging (H4).

3 Study 1: religion and stability-seeking consumption

The purpose of this study was to prime religious concepts to demonstrate that the lack of religious gatherings leads to increased stability-seeking consumption (testing H1).

3.1 Methods

Three hundred adults from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mage = 36.40, SD = 11.58, 42.9% female) participated in this study in exchange for a small cash incentive. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (prime; lack of religious gatherings, religion in general, control). Condition wording for the latter two conditions was adapted from the religious and control primes used by Shachar et al. (2011). Each condition asked participants to write four sentences on a randomly assigned topic (lack of religious gatherings, “how recent changes not allowing you to attend weekly church services and connect with your religious community has affected you”; religion in general, “what your religion means to you personally”; control, “a couple routine activities that you typically do on an average day”). Afterward, participants indicated their stability-seeking consumption behavior with one question directly related to increased purchasing behavior (“If you were at the store now, how many rolls of toilet paper would you be likely to purchase?”). Finally, basic demographics were collected.

3.2 Results

Four participants failed to follow prime instructions and were removed from the dataset, leaving the data from 296 participants for further analysis. An ANOVA revealed a significant difference in stability-seeking consumption behavior among prime conditions, F(2,293) = 4.83, p < .001, partial eta squared = .03. Planned contrasts revealed that the lack of religious gatherings prime resulted in the highest stability-seeking consumption behavior (Mrolls = 14.37, SD = 12.7) in comparison to the religion in general prime (Mrolls = 8.87, SD = 7.78; p = .003) and the control condition (Mrolls = 10.62, SD = 11.24, p = .032). There was no significant difference between the religion in general prime and control condition (p > .3), and no significant differences based on whether consumers indicated that they were religious or not (p > .3).

3.3 Discussion

Fitting with H1, consumers exposed to a lack of religious gatherings prime reported the highest level of stability-seeking consumption behavior in comparison to a general religion prime or control condition, although the effect size was small (i.e., partial eta squared < .06; Cohen 1992). Our findings show that consumers’ lack of in-person religious gatherings is a driver behind higher stability-seeking consumption in response to times of great uncertainty.

4 Study 2: sequential mediation through situational concern and stability from purchasing

The purpose of this study was to confirm the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behavior (testing H2). Additionally, this study sought to test for sequential mediation with explanatory mechanisms for this relationship, namely situational concern and stability found through purchase behavior (testing H3a and H3b, respectively).

4.1 Methods

Two hundred and one adults from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mage = 37.54, SD = 10.93, 33.8% female) participated in this study in exchange for a small cash incentive. Participants first answered questions regarding their current purchase behavior before indicating their level of situational concern, purchase stability beliefs, religiosity, personal effects from the situation, and basic demographics.

4.1.1 Current purchase behavior

To assess current purchase behavior, participants completed three measures. First, participants indicated their level of increased purchasing on a scale from 1 (purchased much less) to 7 (purchased much more) across seven different product categories: toilet paper, canned goods, frozen foods, meat, pantry staples, cleaning supplies, and dairy. Responses were combined to create a scale of increased purchase behavior (M = 4.84, SD = .87, α = .81). Next, participants indicated their present perceived need for more toilet paper on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal) (M = 2.36, SD = 1.29). Afterward, participants answered a question about panic buying—“To what extent have you engaged in panic buying (i.e., buying in much larger quantities than you normally do) during this coronavirus pandemic?” on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal) (M = 2.32, SD = 1.19).

4.1.2 Situational concern

Next, participants completed a 4-item measure assessing their concern regarding the present situation that asked “How much concern do you feel regarding each of the following areas? (1) The coronavirus in general, (2) personally getting the coronavirus, (3) the global impact of the coronavirus, and (4) the impact of the coronavirus on my local community.” Items were assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal) (M = 3.62, SD = .92, α = .85).

4.1.3 Purchase stability beliefs

Participants then completed a 3-item measure to assess how purchasing more products made their life feel more stable: “Purchasing more food, hygiene products, and sanitizing items would make me feel … (1) more secure in my life, (2) more stable in my life, and (3) more like my life is under control” (7-point Likert scales; M = 4.46, SD = 1.58, α = .94).

4.1.4 Religiosity, demographics, and personal effects

Religiosity was measured using Worthington et al.’s (2003) Religious Commitment Inventory (M = 3.25, SD = 2.09, α = .98). Additionally, to better assess the unique influence of religiosity as opposed to other consumer characteristics, numerous demographic characteristics were collected including gender, age, political affiliation, average household income, highest education obtained, and marital status. Political affiliation was assessed on a scale from 1 (strong Democrat) to 7 (strong Republican) (M = 3.43, SD = 1.96). Lastly, to assess personal effects from the current situation, participants were asked to check all that apply from a list of ways they have been personally influenced by the pandemic including (1) I have lost my job, (2) my job’s hours have been reduced, (3) I have had to work from home, (4) I have gotten sick with the coronavirus, (5) I have had to change my daily habits, and (6) I have had to reduce my social connection with others (M = 1.88, SD = 1.07, minimum = 0, maximum = 4).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Regression analysis

First, regression was used to assess the influence of religiosity, demographic characteristics, and personal effects on each of the five outcome variables (situational concern, stability through purchase, increased purchasing, toilet paper need, and panic buying). All models were significant; see Table 1 for regression results.

Across all models, religiosity was the only consistent significant predictor, showing that it is religiosity and not other demographics or personal effects that are driving the findings. Specifically, consumers with higher levels of religiosity expressed greater situational concern and more stability in life after purchasing products. Additionally, participants who were more religious also indicated having increased their purchasing habits, expressed greater need for more toilet paper, and reported higher participation in panic buying behaviors. Note that all of these effects remained significant when the covariates (demographics and personal effects) were not included in the model.

4.2.2 Mediation analysis

Next, mediation analysis was conducted to determine if situational concern and stability through purchase were drivers of increased consumption behavior for consumers with higher levels of religiosity. Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro (model 6) was used to test for sequential mediation using 10,000 bootstrapped samples, controlling for demographics and personal effects.

Findings revealed that religiosity positively and significantly influenced situational concern (b = .09, SE = .03, p = .015, r2 = .10). Situational concern then positively and significantly influenced stability through purchase (b = .61, SE = .11, p < .001, r2 = .26). Lastly, stability through purchase then positively and significantly influenced increased purchasing (b = .15, SE = .04, p < .001, r2 = .32), toilet paper need (b = .19, SE = .06, p = .002, r2 = .30), and panic buying (b = .16, SE = .05, p = .003, r2 = .35). Sequential mediation indirect effects were significant for stability through purchase (b = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI .01 to .02), toilet paper need (b = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI .01 to .02), and panic buying (b = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI .01 to .02). Note that these effects remained significant when the covariates were dropped from the model. See Fig. 1 for the mediation model with path coefficients when including the covariates.

4.3 Discussion

As expected, consumers with higher religiosity levels have increased purchasing behavior in response to a time of great uncertainty, thereby supporting H2. Additionally, religiosity and not other demographics predicted such response, likely due to the fact that religious individuals have their routines disrupted, whereas other demographic traits (e.g., political affiliation) do not result in a weekly disruption to routines. This change in purchase behavior can be explained by greater situational concern and finding stability through purchase behavior, thereby supporting H3a and H3b, respectively. However, it is important to note that the effect sizes for this study were only small to medium (i.e., r2 < .35; Cohen 1992).

What is not completely clear is why consumers who are more religious have greater concern in the first place, given a large body of prior research showing that religious consumers can rely on their faith and religious community for coping during times of need (Harris 1995; Stone et al. 2003). We argue that times of great uncertainty present unique times of need for religious consumers where access to their religious support network is reduced due to restricted social gatherings, leading to increased purchasing as a stability-seeking mechanism to reduce concern.

5 Study 3: decreasing stability-seeking consumption

The purpose of this study was to further confirm the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behavior (testing H2) as well as to test practical implications of our work with governmental messaging using stability-based messaging (testing H4).

5.1 Methods

Two hundred adults from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (Mage = 38.33, SD = 10.42, 44.4% female) participated in this study in exchange for a small cash incentive. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions representing public service announcements (PSA) launched by the government (PSA; stability-based, control). The control PSA was based on pre-existing messaging being used by the government to encourage social distancing to help curb the spread of the disease, while the stability-based messaging encouraged consumers to maintain social connectedness even while following physical distancing guidelines. Next, participants were asked to write two sentences of reactions to the PSA. See Fig. 2 for the stimuli.

After exposure to one of the conditions, participants answered the same questions from study 2 to measure their current purchase behavior, including level of increased purchasing (M = 4.87, SD = .77, α = .81), perceived need for more toilet paper (M = 2.48, SD = 1.39), and panic buying behavior (M = 2.29, SD = 1.32), before indicating their religiosity (M = 3.66, SD = 1.98, α = .98), and basic demographics.

5.2 Results

Thirteen participants failed to follow prime instructions and were removed from the dataset, leaving the data from 187 participants for further analysis. Consistent with study 2, regression analyses revealed that religiosity significantly and positively predicted stability-seeking consumption behaviors including increased purchasing (b = .13, SE = .03, p < .001, r2 = .11), perceived need for more toilet paper (b = .28, SE = .04, p < .001, r2 = .18), and panic buying behavior (b = .32, SE = .04, p < .001, r2 = .23). Results are reported without addition of the demographics from study 2 for simplicity, but all findings remained significant with inclusion of demographics.

Next, and importantly, ANOVA was used to test for differences in stability-seeking consumption behaviors between conditions, after controlling for religiosity. Findings revealed that the stability condition significantly decreased stability-seeking consumption behaviors in comparison to the control condition for both increased purchasing (Mstability = 4.76, SD = .74; Mcontrol = 4.98, SD = .79; F(1,184) = 4.03, p = .046, partial eta squared = .02) and perceived need for more toilet paper (Mstability = 2.26, SD = 1.22; Mcontrol = 2.68, SD = 1.37; F(1,184) = 5.13, p = .025, partial eta squared = .03). While there was not a significant difference between conditions for panic buying behavior (p = .128, partial eta squared = .01), the same pattern of effects emerged with lower panic buying in the stability condition (M = 2.14, SD = 1.23) in comparison to the control condition (M = 2.43, SD = 1.39). Analyses were repeated excluding religiosity as a control, and all effects remained significant.

5.3 Discussion

As expected, consumers with higher levels of religiosity continued to participate in higher levels of stability-seeking consumption, thereby again supporting H2. Notably, we also show that one way to mitigate this effect is through the use of stability-based messaging that helps to decrease such stability-seeking consumption behavior for all consumers, in comparison to the more standardly used social distancing messaging, thereby supporting H4. However, it is worth noting that all effect sizes were only small to medium (i.e., partial eta squared < .06 and r2 < .35; Cohen 1992).

6 General discussion

Through three studies, this research provides an interesting perspective on the relationship between religiosity and stability-seeking consumption behavior. In particular, we show that religiosity’s positive influence on coping through stressful and uncertain times (Bradley et al. 2020; Ellison and George 1994) does not transfer to situations of great uncertainty where access to one’s religious social network is limited. In fact, highly religious consumers are actually the most likely to express situational concern and seek stability through purchasing and, as a result, are more likely to participate in stability-seeking consumption behaviors in comparison to their less or non-religious counterparts. We also find that priming awareness of reduction of in-person religious gatherings increases stability-seeking consumption, while priming stability through public service announcements decreases such behaviors.

6.1 Theoretical contributions

This research builds on the theory of subjective well-being homeostasis (Cummins 2016) and control theory (Mirowsky and Ross 1990) to show the importance of religion in informing when stability-seeking consumption likely occurs. We also focused our examination on stability-seeking consumption behavior in response to times of great uncertainty, which is likely to be different from less uncertain situations where religious consumers are still able to access their consistent routine of religious service attendance and social support from their religious community. Additionally, we build on the growing body of literature examining religion’s influence on consumption (Minton and Kahle 2017; Sarofim and Cabano 2018) to show that religion is critical to incorporate in understanding consumer responses to times of great uncertainty.

6.2 Practical implications

Our research identifies the important influence of religiosity in understanding consumption behavior during times of great uncertainty. In particular, highly religious consumers are the most likely to participate in stability-seeking consumption behaviors. Our findings reveal that not being able to rely upon one’s religious community during these times is a driving force behind such behaviors. As such, religious institutions would be wise to provide explicit discussion on how feeling socially isolated may lead to increased purchasing behavior. Such institutions should also extend beyond just providing virtual religious services but also seek ways to establish virtual social interaction and support on a consistent weekly basis to provide a sense of stability for these consumers.

Marketers and policy makers also have a role to play in supporting religious and non-religious consumers alike during times of great uncertainty. Religious consumers need to feel a sense of consistency, stability, and social support. Alongside the public service announcements from study 3, brands can also provide this through messaging highlighting how they are remaining consistent and will continue to operate by the same high standards as always. Brands may also seek out ways to provide face-to-face interaction with consumers who have questions during this time, such as through virtual video contact forms. Religious consumers can be targeted with such campaigns using social media where targeting religious consumers is easier as consumers self-select into religious groups.

6.3 Limitations and future research directions

Findings are limited to the use of one sample source and testing during one situation of great uncertainty (the coronavirus pandemic). Additionally, effect sizes across all of our studies are only small to medium (Cohen 1992), suggesting that other factors should be considered in the future with more comprehensive stability-seeking consumption models aimed to produce larger effect sizes. Future work should also extend this research to field studies (as best as can be done during a pandemic where social interaction is discouraged) and to other high uncertainty situations. More nuanced methods for priming religion as well as other potential influencers to stability-seeking consumption should be explored (e.g., conservativism, trust in science, uncertainty avoidance).

The influence of religion on other types of stability-seeking consumption behavior, such as increased gun sales during times of great uncertainty (Arnold 2020), should also be explored. Other factors that may influence stability-seeking consumption behavior that should be examined in future research include the following: a consumer’s history with anxiety or depression; instability in other aspects of one’s life (e.g., marital issues); a person’s need for cognitive closure (with those who need more closure being more likely to engage in stability-seeking behavior); stability formation in other areas of life (e.g., with morning regimented outdoor exercise plans); the religious makeup of the community one lives in (with more religious communities likely leading to community-level attitudes about the need for stability-seeking consumption); a consumer’s prior stocking up behaviors (where stability-seeking consumption is likely less if they are already stocked up on essentials); the degree to which other consumers are perceived to be engaging in stability-seeking consumption (with individuals being more likely to stock up on products if they perceive that other consumers are doing so); and differential influences of various personality traits (e.g., susceptibility to interpersonal influence, openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). Additionally, this research was conducted in a Western context with predominantly Christian and non-religious samples. Future research should study these effects in other countries and with consumers from other religious groups.

References

Ammerman, N. T. (2003). Religious identities and religious institutions. In M. Dillon (Ed.), Handbook of the sociology of religion (pp. 207–224). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Arnold, C. (2020). Pandemic and protests spark record gun sales. July 16. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/2020/07/16/891608244/protests-and-pandemic-spark-record-gun-sales

Bailey, J. R., & Raelin, J. D. (2015). Organizations don’t resist change, people do: modeling individual reactions to organizational change through loss and terror management. Organization Management Journal, 12(3), 125–138.

Bradley, C. S., Hill, T. D., Burdette, A. M., Mossakowski, K. N., & Johnson, R. J. (2020). Religious attendance and social support: integration or selection? Review of Religious Research, in press, 1–17.

Brashers, D. E., Neidig, J. L., & Goldsmith, D. J. (2004). Social support and the management of uncertainty for people living with HIV or AIDS. Health Communication, 16(3), 305–331.

Chakravarti, A., & Janiszewski, C. (2003). The influence of macro-level motives on consideration set composition in novel purchase situations. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 244–258.

Choi, Y. (2010). Religion, religiosity, and South Korean consumer switching behaviors. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 157–171.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cummins, R. A. (2016). The theory of subjective wellbeing homeostasis: a contribution to understanding life quality. In F. Maggino (Ed.), A life devoted to quality of life (pp. 61–79). New York: Springer.

Danziger, P. N. (2020). After panic buying subsides, will coronavirus make lasting changed to consumer psychology? March 8. Retrieved April 6, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/pamdanziger/2020/03/08/first-comes-panic-buying-but-afterwards-will-the-coronavirus-leave-lasting-changes-to-consumer-psychology/#4ade90fb77e8

Ellison, C. G., & George, L. K. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 46–61.

Gronmo, S. (1988). Compensatory consumer behavior: elements of a critical sociology of consumption. In P. Otnes (Ed.), The sociology of consumption (pp. 65–85). Oslo: Solum Forlag.

Harris, M. (1995). Quiet care: welfare work and religious congregations. Journal of Social Policy, 24(1), 53–71.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Lamm, E., & Gordon, J. R. (2010). Empowerment, predisposition to resist change, and support for organizational change. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(4), 426–437.

McLafferty, S. (2010). Placing pandemics: geographical dimensions of vulnerability and spread. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 51(2), 143–161.

Minton, E. A., & Kahle, L. R. (2017). Religion and consumer behaviour. In C. V. Jansson-Boyd & M. J. Zawisza (Eds.), International handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 292–311). New York: Routledge.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1990). Control or defense? Depression and the sense of control over good and bad outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31(1), 71–86.

PEW. (2017). The changing global religious landscape. April 4. Retrieved January 11, 2018, from http://www.pewforum.org/2017/04/05/the-changing-global-religious-landscape/

Sadique, M. Z., Edmunds, W. J., Smith, R. D., Meerding, W. J., De Zwart, O., Brug, J., & Beutels, P. (2007). Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(9), 1307–1313.

Sarofim, S., & Cabano, F. G. (2018). In god we hope, in ads we believe: the influence of religion on hope, perceived ad credibility, and purchase behavior. Marketing Letters, 29(3), 391–404.

Schmidt, R., Sager, G. C., Carney, G. T., Muller, A. C., Zanca, K. J., Jackson, J. J., . . . Burke, J. C. (2014). Patterns of religion (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Schwartz, S. H., & Huismans, S. (1995). Value priorities and religiosity in four western religions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(2), 88–107.

Shachar, R., Erdem, T., Cutright, K. M., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2011). Brands: the opiate of the nonreligious masses? Marketing Science, 30(1), 92–110.

Stone, H. W., Cross, D. R., Purvis, K. B., & Young, M. J. (2003). A study of the benefit of social and religious support on church members during times of crisis. Pastoral Psychology, 51(4), 327–340.

Stroope, S. (2012). Social networks and religion: the role of congregational social embeddedness in religious belief and practice. Sociology of Religion, 73(3), 273–298.

Vázquez-Casielles, R., del Río-Lanza, A. B., & Díaz-Martín, A. M. (2007). Quality of past performance: impact on consumers’ responses to service failure. Marketing Letters, 18(4), 249–264.

Worthington, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., Schmitt, M. M., Berry, J. T., Bursley, K. H., & O’Connor, L. (2003). The religious commitment inventory-10: development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Minton, E.A., Cabano, F.G. Religiosity’s influence on stability-seeking consumption during times of great uncertainty: the case of the coronavirus pandemic. Mark Lett 32, 135–148 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09548-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09548-2