Abstract

Objectives

The New York City Police Department’s “Summer All Out” (SAO) initiative was a 90-day, presence-based foot patrol program in a subset of the city’s patrol jurisdictions.

Methods

We assessed the effectiveness of SAO initiative in reducing crime and gun violence using a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach.

Results

Results indicate the SAO initiative was only associated with significant reductions in specific property offenses, not violent crime rates. Foot patrols did not have a strong, isolating impact on violent street crime in 2014 or 2015. Deployments on foot across expansive geographies also have a weak, negligible influence on open-air shootings.

Conclusions

The findings suggest saturating jurisdictions with high-visibility foot patrols has little influence on street-level offending, with no anticipatory or persistent effects. Police departments should exercise caution in deploying foot patrols over large patrol jurisdictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

03 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09483-w

Notes

Because this was not a permanent transfer, New York State labor laws would mandate remuneration for employees traveling to participate in this department-sponsored initiative. Contractually, participating officers were entitled to 2 hours and 30 minutes of “travel time” to travel to, and from, their temporary assignments. Monies granted for “travel time” are payable to NYPD officers at their regular hourly rate. Although incurred travel time is not calculated at a traditional overtime rate, it is still subject to normal overtime reporting protocols. The “travel time” rate for an NYPD officer with more than 5.5 years of service is $44.77 per hour, which equates to approximately $112 of overtime earnings per officer, per day. Assuming officers worked traditional 8-hour shifts with steady days off, we would expect a total of 60 work appearances during the intervention phase.

The details of “Operation 25” were found in a pamphlet published internally by the NYPD. Wilson (2013) offers a more in-depth appraisal of the program.

Crime remained unchanged in one experimental beat.

The NYPD does not publish their staffing metrics. We only received aggregated summary statistics of deployed SAO personnel.

Because precinct commanders were given discretion in their deployment of SAO officers, the spatial reach of each precinct’s SAO contingent within precincts is largely unknown. It is unlikely that deployment of foot patrols was intended to evenly saturate the precinct aerial unit. Despite this, the distribution of SAO officers was widespread enough to warrant the designation of the precinct jurisdiction as the primary unit of analysis.

Anecdotal evidence gleaned from interviews with participating officers indicates that many policed street segments on foot—alone. In general, the diffuse dispersal of individual foot patrol units improved the spatial reach of SAO officers within precincts.

The magnitude of disengagement cannot be overstated. In 2014, the NYPD initiated approximately 150,000 fewer stops of individuals suspected of criminality than in the previous year. Data is publicly accessible on the following webpage: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/reports-analysis/stopfrisk.page

The federal monitor’s reports on police stops in New York City suggest a widespread practice of underreporting. Some estimates suggest nearly half of all stops remain undocumented. In spite of the monitor’s findings, the sharp reduction in street stops following Floyd is still noteworthy, even if it may be an overestimate. Access to the monitor’s semi-annual reports can be found here: http://nypdmonitor.org/monitor-reports/

The SAO initiative was also designed to combat crime occurring in Police Service Areas (PSAs). Officers assigned to PSAs patrol New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) facilities and grounds. Because NYCHA properties are scattered throughout the City of New York, some PSA boundaries span several precincts. Many NYCHA developments are nested within precinct jurisdictions subjected to the initiative, though jurisdictional responsibility lies with the PSA. Officers assigned to precincts typically police all areas within precinct boundaries except NYCHA property. Some SAO officers were deployed to saturate PSA jurisdictions via foot patrols. Because the units of analysis are large and we did not know a priori the deployment strategy of PSA officers, we do not compare PSA crime to precinct crime.

NYPD officials did not explicitly disclose their selection criteria for participating jurisdictions. The composition of the treatment group suggests indicators of violence were considered, which are often weighted by other precinct characteristics such population size and density. Many of the NYPD’s 77 precinct jurisdictions never received a summer contingent of surplus guardianship. Other regions of the city with similarly pressing crime and disorder concerns were not included; this is due, in part, to the limited availability of personnel to saturate all jurisdictions equally. This supports, to a certain degree, the “randomness” of precinct selection.

Four precincts were excluded from the control group. The Central Park Precinct is an expansive recreational environment without an official residential population. Victims of crime are representative of the ambient population visiting the park, which precludes any accurate assessment of per capita crime rates. Likewise, the 14th and 18th Precincts in midtown Manhattan typically have large ambient populations far surpassing their residential populations. The 121st Precinct in Staten Island was summarily excluded because this area was not officially recognized as a precinct jurisdiction until the summer of 2013.

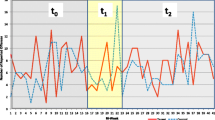

Empirical testing of common group trends is akin to a placebo treatment procedure whereby crime outcomes are regressed on interactions between a treatment indicator and a full series of T − 1 dummies for months (St. Clair and Cook 2015). Coefficients on the interaction terms represent the conditional outcome distribution over time. Statistically significant differences should only arise when the treatment group enters into the treatment condition. Alternatively, one could test for nonequivalence of the group-level trends using only pre-intervention outcomes (Ryan 2009). In either setting, the pre-period coefficients associated with several of New York City’s major crime indices were indistinguishable from zero, supporting the assumption of trend equivalence.

As New York City’s major crime indices drop to historic lows, differences in crime rates across time show greater volatility—in percentages—than in their actual counts. CompStat evaluations typically compare counts of crimes in one jurisdiction with itself in the previous year. Even meager differences over time in aggregate offense counts, if small, can produce large percentage changes. We contend that police officials might overestimate the severity of even a modest crime spike. Baseline deviations in crime are not likely to persist, or be demonstrative of a significant historical divergence in trend.

Violent crime is a composite index comprising murder/non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and felonious assault. Later, we disaggregate composite measures to examine the effect of the SAO initiative on specific crime types.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the NYC OpenData portal (https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Public-Safety/NYC-crime/qb7u-rbmr).

Hospital physicians and superintendents are mandated to report bullet wounds to police authorities, and any failure to do so is a class “A” misdemeanor according to the New York State Penal Law (see, e.g., § 265.25).

The NYPD’s shooting database did not record any incident-level data for three jurisdictions over the 60-month observation period. The 17th, 19th, and 111th Precincts did not report any open-air shooting incidents during our window of observation; these were removed from our group of controls.

Index crime is comprised of “seven major” crime types: murder/non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, grand larceny, and grand larceny auto. These crimes are regularly tracked and monitored as part of the NYPD’s CompStat system.

In all instances, log(.) denotes the natural logarithm. The absence of crime reports in any particular month is imputed with a value of 1 to facilitate this transformation.

Note, we adjust for obvious controls such as population and area, even though they do not assist with the identification of our causal parameter of interest. If any observed precinct characteristics do change across time, they change slowly. For example, the 121st Precinct in Staten Island was not officially recognized as a precinct jurisdiction until late 2013. The 121st Precinct absorbed sector boundaries within neighboring precincts to alleviate their workload. In general, the inclusion of precinct-level controls does not appreciably influence our results. In fact, double-differencing in this context produces results similar to the standard fixed effects estimator, and so our models will silently exclude many time-invariant controls once we allow for the estimation of precinct- and time-specific intercepts. Also, our equations are insensitive to the inclusion of precinct population weights.

Perhaps one could delineate a theoretical framework for a surge in violence in response to the imminence of the intervention. If public announcements are perceived early, it signals to offenders the “absence” of formal guardianship in public spaces in the weeks before the onset of foot patrol deployments.

Our review of the DiD literature suggests there is no clear consensus regarding the optimal lead-lag structure. DiD studies investigating anticipatory effects often assess anywhere from one-to-three lead effects before treatment exposure (e.g., Autor 2003; Cavalcanti et al. 2019; Green et al. 2014; Grinols and Mustard 2006; MacDonald et al. 2016). It is also not uncommon to find DiD evaluations report lead effects more than three periods before program/policy adoption (Azoulay et al. 2019; Venkataramani et al. 2019). In other settings, anticipatory effects are largely ignored and the authors only incorporate a static intervention dummy (Braga et al. 2018; Larsen et al. 2015).

The classic DiD framework with two groups and a standardized time index for post-treatment months could only be estimated separately by year. One-way cluster robust standard errors, clustering on precinct, are less conservative than least-squares estimates assuming independent and identically distributed errors. We also estimated nonparametric variance-covariance matrices adopted by Driscoll and Kraay (1998), which are amendable to settings with dependence across cross-sectional units. This alternative uncertainty estimator is not appreciably different than standard “sandwich” estimators that cluster on precinct.

The calendar month immediately prior to program implementation in both years serves as the reference period. Excluded periods include June in 2014 and May in 2015.

We do not model months earlier than January in both years.

Few open-air drug and weapon-related offenses occur across months. Non-ignorable differences in pre-treatment reporting trends may be partially responsible for any observed anticipatory effects. Drug and/or weapon-related crime reporting is typically fueled by geographically-focused arrest-generating activities. For example, the staffing of specialized units dedicated exclusively to narcotics enforcement has dwindled heavily in recent years, and as a result, their intensity has been concentrated in more drug-prone regions of the city. Anecdotal evidence suggests narcotics-related activity intensified in the pre-intervention period, as heightened SAO guardianship would typically disrupt the execution of “plainclothes” operations. Further, narcotics-related arrests, in general, have been declining over time. Most of the observed drug and/or weapon-related offenses in our sample involve crimes of simple possession. In particular, most reports involving drug possession are consistent with personal use—not distribution. Similarly, most weapon-related offense reports are consistent with non-firearm-related possession (e.g., knives and other blunt instruments). The SAO model of crime prevention was not designed to be an arrest-generating intervention strategy. Rather, most officers were encouraged to prevent crime by exercising their visible presence on street segments. We argue that any increase in drug and weapon-related reporting are unlikely to be the result of intensifying visible foot patrols.

Restricting burglary complaints to a subset of street offenses is limiting. Too few burglaries occur in public domains. To illustrate, larcenies from vehicles used by persons for commercial or business purposes would be classified as a burglary according to the New York State Penal Law (see, e.g., §140.00 definition of “building”). Offenses of this type typically occur on visible street segments when the vehicle is unattended, and would be classified as a “street” burglary for crime reporting purposes. Less than 5% of burglaries for the years under study were listed as street offenses. Log-linear leastsquares estimates would be affected by small per capita rates and low cardinality over time.

Assessing crime displacement to nearby street segments is a complicated endeavor due to large units of analysis. Absent the precise deployment of foot patrols to micro-locations within precinct jurisdictions, we cannot directly quantify how the widespread surge in police presence affected adjacent beats or sectors.

The coefficients in the pre-period were positive and relatively large in magnitude. The “absorbing” influence of pre-period dummies (i.e., “lead” indicators) has been observed in other place-based evaluation strategies, particularly those where self-selection of jurisdictions into treatment was suggested. In their analysis of Operation Impact in New York City, MacDonald et al. (2016) observed that effects were weaker once they modeled the two periods before program exposure.

Some reported crime metrics were more infrequent than others across time. Coefficients associated with several non-composite crime metrics (e.g., drug/weapon offenses), have small offense counts at the street-level, and thus their rates will typically have high variance. On the other hand, the NYPD’s composite crime indices (e.g., index crime) is more precisely estimated, as indicated by their tighter confidence bands.

Over the 60-month observation period, the SAO policy dummy intermittently indexes a subset of precinct jurisdictions during two discrete but qualitatively similar iterations (i.e., \( {SAO}_{pt}^{14} \) and \( {SAO}_{pt}^{15} \)). Again, the variable SAOpt is a dummy equal to unity if a precinct participated in the SAO initiative at any time and it was in the post-exposure epoch (i.e., the 90-day intervention phase). We dub SAOpt a static effect because it is a simple dummy intervention. Our goal is to assess the effects of the SAO initiative on open-air gun violence absent any time-varying treatment structure.

The NYPD has eight patrol boroughs. The boroughs of Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan are split into a northern patrol borough and a southern patrol borough. Each has clearly demarcated borders and is headed by a separate borough commander in charge of patrol operations. This is a qualitatively different hierarchical position in the NYPD rank structure. A precinct commander is in charge of patrol operations within the confines of his or her assigned precinct. The borough commander will oversee all precinct commanders within the same patrol borough. Matching SAO jurisdictions with their patrol borough counterparts overlooks city sections where shootings do not cluster. Many of the future and previous receivers of the SAO initiative were sampled by NYPD executives from within the same patrol borough, offering a more homogenous counterfactual grouping.

Shooting lead coefficients close to the SAO effective dates were mostly positive in both years, and a bit more precisely estimated in 2015. Though anticipatory effects were of substantive interest in this evaluation, we were also concerned with selection of SAO jurisdictions into treatment on the basis of past outcomes. The latter concern is entirely plausible and is one of the reasons we modeled the shooting data more rigorously than the NYPD’s standard crime metrics.

Any precinct-specific linear or higher order polynomial trend fully absorbs the persistent effect observed in 2014.

Augmenting visible guardianship on street segments might affect the perception of offending risk in non-SAO jurisdictions if foot patrols concentrated near the periphery of SAO precinct borders—or beyond. Discarding all neighbors thus compares SAO precincts with those jurisdictions that are more geospatially remote. We have no evidence that a nonadjacent counterfactual would be influenced by the widespread surge in foot patrols within SAO precincts. As well, if SAO officers were deployed on foot directly from their assigned SAO precincts—and not from their previous administrative facilities—then marked vehicular travel to and from SAO precincts would not inadvertently create the impression of more police presence within non-SAO precincts. The perception of police intensity in comparison areas is a noteworthy critique in experimental studies and biases results towards zero (see Larson 1975). Our understanding of the intervention suggests SAO exposure respected precinct boundaries, though we cannot completely rule out treatment spillover.

Operation Impact was in effect from January 2003 to mid-July 2014.

The NYPD mandated that all SAO officers receive, in aggregate, a 1-day refresher course to reacclimate members to street-level patrol work. We have no evidence that attendees received detailed instruction regarding any community-derived intelligence specific totheir individually assigned jurisdictions.

Maintaining the perception of increased guardianship over time is not easy. The NYPD did not sanction any governing body to ensure the visibility of SAO officers during the intervention phase. Supervision of SAO personnel was relegated to the supervisory staff permanently assigned to participating SAO jurisdictions. Thus, as the rank-and-file staff increased due to the influx of SAO personnel, the supervisory component did not. Throughout the initiative, patrol supervisors were thus in charge of supervising regular patrol duty operations and ensuring the continued visibility of the SAO contingent on foot. This greatly increases the “span of control” of supervisory members at the local level and should not be understated. We have no evidence that precinct-level supervisors were making frequent or varied visits to SAO officers on foot. In sum, if foot deployments were too sparse and sufficiently interrupted by officer absence from their assigned posts, then the perception of “more presence” is even more diluted.

References

Abadie, A., & Dermisi, S. (2008). Is terrorism eroding agglomeration economies in Central Business Districts? Lessons from the office real estate market in downtown Chicago. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 451–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.04.002.

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D. H., & Lyle, D. (2004). Women, war, and wages: The effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at midcentury. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 497–551. https://doi.org/10.1086/383100.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An Empiricist's companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Apel, R. (2013). Sanctions, perceptions, and crime: Implications for criminal deterrence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 29(1), 67–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-012-9170-1.

Autor, D. H. (2003). Outsourcing at will: The contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1086/344122.

Azoulay, P., Fons-Rosen, C., & Graff Zivin, J. S. (2019). Does science advance one funeral at a time? American Economic Review, 109(8), 2889–2920. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161574.

Baumer, E. P., & Wolff, K. T. (2014). Evaluating contemporary crime drop(s) in America, New York City, and many other places. Justice Quarterly, 31(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.742127.

Beccaria, C. (1963). On crimes and punishments. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355304772839588.

Blundell, R., & MaCurdy, T. (1999). Labor supply: A review of alternative approaches. In O. C. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1559–1695). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bowers, W. J., & Hirsch, J. H. (1987). The impact of foot patrol staffing on crime and disorder in Boston: An unmet promise. American Journal of Policing, 6, 17–44.

Braga, A. A., & Bond, B. J. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: A randomized control trial. Criminology, 46(3), 577–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00124.x.

Braga, A. A., & Weisburd, D. L. (2012). The effects of focused deterrence strategies on crime: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 49(3), 323–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427811419368.

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2012). Hot spots policing effects on crime. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 8. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2012.8.

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V., & Hureau, D. M. (2014). The effects of hot spots policing on crime: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 31(4), 633–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.673632.

Braga, A. A., Weisburd, D., & Turchan, B. (2018). Focused deterrence strategies and crime control. Criminology & Public Policy, 17(1), 205–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12353.

Braga, A. A., Zimmerman, G., Barao, L., Farrell, C., Brunson, R. K., & Papachristos, A. V. (2019). Street gangs, gun violence, and focused deterrence: Comparing place-based and group-based evaluation methods to estimate direct and spillover deterrent effects. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427818821716.

Branas, C. C., Cheney, R. A., MacDonald, J. M., Tam, V. W., Jackson, T. D., & Ten Have, T. R. (2011). A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(11), 1296–1306. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr273.

Brown, M. K. (1988). Working the street: Police discretion and the dilemmas of reform. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2011). Robust inference with multiway clustering. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 29(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1198/jbes.2010.07136.

Cavalcanti, T., Da Mata, D., & Toscani, F. (2019). Winning the oil lottery: The impact of natural resource extraction on growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 24(1), 79–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-018-09161-z.

Chainey, S., & Ratcliffe, J. H. (2005). GIS and crime mapping. New York: Wiley.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589.

Cook, P. J. (1980). Research in criminal deterrence: Laying the groundwork for the second decade. Crime and Justice, 2, 211–268. https://doi.org/10.1086/449070.

Corsaro, N., & Engel, R. S. (2015). Most challenging of contexts: Assessing the impact of focused deterrence on serious violence in New Orleans. Criminology & Public Policy, 14(3), 471–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12142.

Cowell, B. M., & Kringen, A. L. (2016). Engaging communities one step at a time: Policing’s tradition of foot patrol as an innovative community engagement strategy. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

Cullen, F. T., & Pratt, T. C. (2016). Toward a theory of police effects. Criminology & Public Policy, 15(3), 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12231.

Driscoll, J. C., & Kraay, A. C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(4), 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465398557825.

Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kremer, M. (2007). Using randomization in development economics research: a toolkit. In T. P. Schultz & J. A. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of Development Economics (Vol. 4, pp. 3895–3962). Elsevier.

Eck, J. E. (2015). Who should prevent crime at places? The advantages of regulating place managers and challenges to police services. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 9(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pav020.

Eck, J. E., & Maguire, E. R. (2006). Have changes in policing reduced violent crime? An assessment of the evidence. In A. Blumstein & J. Wallman (Eds.), The crime drop in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eck, J. E., & Weisburd, D. L. (1995). Crime places in crime theory. In J. E. Eck & D. L. Weisburd (Eds.), Crime and place. Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Eterno, J. A., & Silverman, E. B. (2012). The crime numbers game: Management by manipulation. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Felson, M. (1994). Crime and everyday life: Insight and implications for society. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Felson, M. (1995). Those who discourage crime. In J. E. Eck & D. L. Weisburd (Eds.), Crime and place. Monsey: Criminal Justice Press.

Floyd et al. (2013) v. City of New York, et al., 959 F. Supp. 2d 540.

Gertler, P. J., Martinez, S., Premand, P., Rawlings, L. B., & Vermeersch, C. M. J. (2016). Impact evaluation in practice (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912791.

Green, C. P., Heywood, J. S., & Navarro, M. (2014). Did liberalising bar hours decrease traffic accidents? Journal of Health Economics, 35, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.03.007.

Grinols, E. L., & Mustard, D. B. (2006). Casinos, crime, and community costs. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.2006.88.1.28.

Haberman, C. P., & Stiver, W. H. (2018). The Dayton foot patrol program: An evaluation of hot spots foot patrols in a Central Business District., 0(0), 1098611118813531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611118813531.

Kelling, G. L., Pate, A., Dieckman, D., & Brown, C. E. (1974). The Kansas City preventive patrol experiment. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

Kelling, G. L., Pate, A., Ferrara, A., Utne, M., & Brown, C. E. (1981). The Newark foot patrol experiment. Washington, DC: Police Foundation.

Kennedy, D. M. (2016). Community crime prevention. In T. G. Blomberg, J. M. Brancale, K. M. Beaver, & W. D. Bales (Eds.), Advancing criminology and criminal justice policy (pp. 92–103). New York: Routledge.

Kleck, G., & Barnes, J. C. (2014). Do more police lead to more crime deterrence? Crime & Delinquency, 60(5), 716–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128710382263.

Kochel, T. R. (2011). Constructing hot spots policing: Unexamined consequences for disadvantaged populations and for police legitimacy. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 22(3), 350–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403410376233.

Krivo, L. J. (2014). Placing the crime decline in context: A comment on Baumer and Wolff. Justice Quarterly, 31(1), 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.742125.

Kubrin, C. E., Messner, S. F., Deane, G., McGeever, K., & Stucky, T. D. (2010). Proactive policing and robbery rates across U.S. cities. Criminology, 48(1), 57–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00180.x.

Larsen, B. Ø., Kleif, H. B., & Kolodziejczyk, C. (2015). The volunteer programme ‘Night Ravens’: A difference-in-difference analysis of the effects on crime rates. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 16(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14043858.2015.1015810.

Larson, R. C. (1975). What happened to patrol operations in Kansas city? A review of the Kansas city preventive patrol experiment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 3(4), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(75)90034-3.

Lechner, M. (2011). The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference methods. Foundations and Trends® in Econometrics, 4(3), 165–224. https://doi.org/10.1561/0800000014.

Lum, C., Koper, C. S., & Telep, C. W. (2011). The evidence-based policing matrix. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9108-2.

MacDonald, J., Fagan, J., & Geller, A. (2016). The effects of local police surges on crime and arrests in New York City. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157223.

Macedo, D., Schuck, G., & Kramer, M. (2015). NYPD cops flood high-crime areas in ‘Summer All Out’ initiative. WLNY TV 10/55 – CBS New York.

Manning, P. K. (1977). Police work: The social Organization of Policing. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Marvell, T. B., & Moody, C. E. (1996). Specification problems, police levels, and crime rates. Criminology, 34(4), 609–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1996.tb01221.x.

Mazeika, D. M. (2014). General and specific displacement effects of police crackdowns: criminal events and “local” criminals. (Ph.D. Dissertation), University of Maryland, College Park.

Meyer, B. D. (1995). Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 13(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1995.10524589.

Nagin, D. S. (2013). Deterrence in the twenty-first century. Crime and Justice, 42(1), 199–263. https://doi.org/10.1086/670398.

Nagin, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (2019). The real gold standard: Measuring counterfactual worlds that matter most to social science and policy. Annual Review of Criminology, 2(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-011518-024838.

Nagin, D. S., Solow, R. M., & Lum, C. (2015). Deterrence, criminal opportunities, and police. Criminology, 53(1), 74–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12057.

National Research Council. (2004). Fairness and effectiveness in policing: The evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nixon, T. S., & Barnes, J. C. (2018). Calibrating student perceptions of punishment: A specific test of general deterrence. American Journal of Criminal Justice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-018-9466-2.

Novak, K. J., Fox, A. M., Carr, C. M., & Spade, D. A. (2016). The efficacy of foot patrol in violent places. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 12(3), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9271-1.

Osgood, D. W. (2000). Poisson-based regression analysis of aggregate crime rates. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007521427059.

Pate, A. M. (1986). Experimenting with foot patrol: The Newark experience. In D. P. Rosenbaum (Ed.), Community crime prevention: Does it work? Newbury Park: Sage.

Pedraja-Chaparro, F., Santín, D., & Simancas, R. (2016). The impact of immigrant concentration in schools on grade retention in Spain: A difference-in-differences approach. Applied Economics, 48(21), 1978–1990. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1111989.

Petersen, M. A. (2008). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn053.

Pickett, J. T., & Roche, S. P. (2016). Arrested development: Misguided directions in deterrence theory and policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 15(3), 727–751. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12217.

Piza, E. L. (2018). The effect of various police enforcement actions on violent crime: Evidence from a saturation foot-patrol intervention. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 29(6–7), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403417725370.

Piza, E. L., & O’Hara, B. A. (2014). Saturation foot-patrol in a high-violence area: A quasi-experimental evaluation. Justice Quarterly, 31(4), 693–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.668923.

Pogarsky, G., & Loughran, T. A. (2016). The policy-to-perceptions link in deterrence. Criminology & Public Policy, 15(3), 777–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12241.

Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Blevins, K. R., Daigle, L. E., & Madensen, T. D. (2006). The empirical status of deterrence theory: A meta-analysis. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory, 15, 367–396.

Press, S. J. (1971). Some effects of an increase in police manpower in the 20th Precinct of New York City. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Ratcliffe, J. H., Taniguchi, T., Groff, E. R., & Wood, J. D. (2011). The Philadelphia Foot Patrol Experiment: A randomized controlled trial of police patrol effectiveness in violent crime hotspots. Criminology, 49(3), 795–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00240.x.

Reaves, B. A. (2015). Local police departments, 2013: Personnel, policies, and practices. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Risman, B. J. (1980). The Kansas City preventive patrol experiment: A continuing debate. Evaluation Review, 4(6), 802–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x8000400605.

Rosenbaum, D. P. (2006). The limits of hot spots policing. In D. Weisburd & A. A. Braga (Eds.), Police innovation: Contrasting perspectives (pp. 245–263). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenbaum, D. P., & Lurigio, A. J. (1994). An inside look at community policing reform: Definitions, organizational changes, and evaluation findings. Crime & Delinquency, 40(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128794040003001.

Ryan, A. M. (2009). Effects of the premier hospital quality incentive demonstration on Medicare patient mortality and cost. Health Services Research, 44(3), 821–842. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00956.x.

Ryan, A. M., Burgess, J. F., & Dimick, J. B. (2015). Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Services Research, 50(4), 1211–1235. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12270.

Sampson, R. J. (2010). Gold standard myths: Observations on the experimental turn in quantitative criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-010-9117-3.

Sampson, R. J., & Cohen, J. (1988). Deterrent effects of the police on crime: A replication and theoretical extension. Law and Society Review, 22(1), 163–189. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053565.

Schmidheiny, K., & Siegloch, S. (2019). On Event studies and distributed-lags in two-way fixed effects models: identification, equivalence, and generalization. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP13477.

Sherman, L. W. (1990). Police crackdowns: Initial and residual deterrence. Crime and Justice, 12, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1086/449163.

Sherman, L. W. (2013). The rise of evidence-based policing: Targeting, testing, and tracking. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research (Vol. 42). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sherman, L. W., & Weisburd, D. (1995). General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime “hot spots”: A randomized, controlled trial. Justice Quarterly, 12(4), 625–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829500096221.

Sherman, L. W., Gartin, P. R., & Buerger, M. E. (1989). Hot spots of predatory crime: Routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology, 27(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb00862.x.

Smith, M. J., Clarke, R. V., & Pease, K. (2002). Anticipatory benefits in crime prevention. Crime Prevention Studies, 13, 71–88.

Sorg, E. T., Haberman, C. P., Ratcliffe, J. H., & Groff, E. R. (2013). Foot patrol in violent crime hot spots: The longitudinal impact of deterrence and posttreatment effects of displacement. Criminology, 51(1), 65–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00290.x.

Sorg, E. T., Wood, J. D., Groff, E. R., & Ratcliffe, J. H. (2017). Explaining dosage diffusion during hot spot patrols: An application of optimal foraging theory to police officer behavior. Justice Quarterly, 34(6), 1044–1068. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2016.1244286.

St. Clair, T., & Cook, T. D. (2015). Difference-in-differences methods in public finance. National Tax Journal, 68(2), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2015.2.04.

Sweeten, G. (2016). What works, what doesn't, what's constitutional? Criminology & Public Policy, 15(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12176.

Telep, C. W., & Hibdon, J. (2018). Community crime prevention in high-crime areas: The Seattle Neighborhood Group Hot Spots Project. City & Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12342.

Telep, C. W., & Weisburd, D. (2018). The criminology of places. In G. Bruinsma & S. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 583–603). New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, S. B. (2011). Simple formulas for standard errors that cluster by both firm and time. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.08.016.

Trojanowicz, R. C., & Baldwin, R. (1982). An evaluation of the neighborhood foot patrol program in Flint, Michigan. East Lansing: Michigan State University.

Venkataramani, A. S., Cook, E., O’Brien, R. L., Kawachi, I., Jena, A. B., & Tsai, A. C. (2019). College affirmative action bans and smoking and alcohol use among underrepresented minority adolescents in the United States: A difference-in-differences study. PLoS Medicine, 16(6), e1002821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002821.

Wakefield, A. (2007). Carry on constable? Revaluing foot patrol. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 1(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pam038.

Weisburd, D. (2015). The law of crime concentration and the criminology of place. Criminology, 53(2), 133–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12070.

Weisburd, D., Wyckoff, L. A., Ready, J., Eck, J. E., Hinkle, J. C., & Gajewski, F. (2006). Does crime just move around the corner? A controlled study of spatial displacement and diffusion of crime control benefits. Criminology, 44(3), 549–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00057.x.

Weisburd, D., Morris, N. A., & Ready, J. (2008). Risk-focused policing at places: An experimental evaluation. Justice Quarterly, 25(1), 163–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820801954647.

Weisburd, D., Hinkle, J. C., Famega, C., & Ready, J. (2011). The possible “backfire” effects of hot spots policing: An experimental assessment of impacts on legitimacy, fear and collective efficacy. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(4), 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-011-9130-z.

Weisburd, D., Groff, E. R., & Yang, S.-M. (2014). Understanding and controlling hot spots of crime: The importance of formal and informal social controls. Prevention Science, 15(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0351-9.

Wilson, J. Q. (1968). Varieties of police behavior: The Management of law and Order in eight communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, J. Q. (2013). Thinking About Crime: Basic books.

Wilson, J. Q., & Boland, B. (1978). The effect of the police on crime. Law and Society Review, 12(3), 367–390. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053285.

Wilson, J. Q., & Kelling, G. L. (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic Monthly, March, 29–38.

Wing, C., Simon, K., & Bello-Gomez, R. A. (2018). Designing difference in difference studies: Best practices for public health policy research. Annual Review of Public Health, 39(1), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce Laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1802–1820. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.5.1802.

Wood, J. D., Sorg, E. T., Groff, E. R., Ratcliffe, J. H., & Taylor, C. J. (2014). Cops as treatment providers: Realities and ironies of police work in a foot patrol experiment. Policing and Society, 24(3), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2013.784292.

Zimring, F. E. (2012). The City that became safe: New York’s lessons for urban crime and its control. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimring, F. E., & Hawkins, G. J. (1973). Deterrence: The legal threat in crime control. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Some data in Table 2 footnote were not made. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the erratum/correction for this article.

The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of the New York City Police Department.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bilach, T.J., Roche, S.P. & Wawro, G.J. The effects of the Summer All Out Foot Patrol Initiative in New York City: a difference-in-differences approach. J Exp Criminol 18, 209–244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09445-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09445-8