Abstract

Healthcare workers are under such a tremendous amount of pressure during the COVID-19 pandemic that many have become concerned about their jobs and even intend to leave them. It is paramount for healthcare workers to feel satisfied with their jobs and lives during a pandemic. This study aims to examine the predictors of job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 10 and 30 April 2020, 240 healthcare workers in Bolivia completed a cross-sectional online survey, which assessed their job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The results revealed that their number of office days predicted job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention, but the relationships varied by their age. For example, healthcare workers’ office days negatively predicted job satisfaction for the young (e.g., at 25 years old: b = − 0.21; 95% CI: − 0.36 to − 0.60) but positively predicted job satisfaction for the old (e.g., at 65 years old: b = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.44). These findings provide evidence to enable healthcare organizations to identify staff concerned about job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention to enable early actions so that these staffs can remain motivated to fight the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

In the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers are experiencing unprecedented pressure from stressors including but not limited to enormous workload, virus exposure, inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE), moral dilemmas, work incivility, despair, isolation from family, and discrimination (Lai et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020a) and even fake news (Alvarez-Risco et al. 2020; O’Connor and Murphy 2020) and conspiracy theory (Chen et al. 2020). An emergency physician in Washington DC, Thomas Kirsch, asked on March 24, 2020, “How much risk do healthcare workers have to take? Or, more bluntly: How many of us will die before we start to walk away from our jobs?” (Kirsch 2020). Many healthcare workers stopped showing up at work once COVID-19 hit the USA, due to the shortage of PPE (Cloherty 2020). Such issues can be more severe in less developed economies. For instance, media reported over 100 nurses stopped coming to work on one single day in a hospital in South America (Galdos 2020).

In this critical time of the COVID pandemic, it is paramount for healthcare workers to feel satisfied with their current jobs and lives without intention to leave their jobs. However, little research has studied the job-related variables of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The existing research on healthcare workers under COVID-19 has focused on workers’ mental health and well-being (c.f. a meta-analysis by Pappa et al. 2020; Tang et al. 2020). This study presents the first attempt to document healthcare workers’ job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention, and their predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

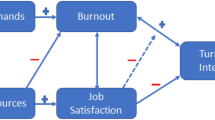

We aim to examine the predictive effect on the job-related outcome variables by several canonical risk factors of mental health issues in the pandemic such as age, gender, and education (Lai et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2020; Yáñez et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020a). We are also interested in healthcare workers’ job-related characteristics, such as office days, and whether they are temporary staff or redeployed during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the burgeoning evidence that those variables can predict satisfaction and/or turnover intention in the ongoing pandemic (Labrague and Santos 2020; Zhang et al. 2020a, b). These predictors can help healthcare organizations to be more specific in developing evidence-based screening for mental health, job satisfaction, and turnover issues of their staff during the COVID-19 pandemic (Yang et al. 2020).

Methods

Bolivia, with the lowest GDP per capita in South America, lacks adequate health infrastructure (Arigho-Stiles 2020). COVID-19 cases appeared in Bolivia on March 10, 2020, and on March 25, 2020, Bolivia declared COVID-19 a national health emergency. COVID-19 has since spread quickly, generating enormous pressure on the country’s healthcare workers. Media reported healthcare workers in several hospitals turned away COVID-19 patients out of concern over the limited resources in overcrowded facilities (Laing and Ramos 2020). On April 23, 2020, Bolivian health workers protested publicly about shortages of PPE and other supplies, including body bags for the dead (Requena 2020). And the dire situation continues to worsen as the COVID-19 pandemic deepens in Bolivia.

This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guideline. All participants agreed with their informed consent to enroll in the online survey. Strict confidentiality was assured in the data collection processes was voluntary. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tsinghua University (20200322). We sent out our online survey, developed in English and back translated into Latin American Spanish, to 402 healthcare workers in 83 healthcare facilities (40 in La Paz, 11 in Santa Cruz, and 32 from other administrative regions) in Bolivia from April 10 to April 30, 2020, 1 month into the COVID-19 emergency in Bolivia. The survey was open to healthcare workers in healthcare institutions such as hospitals, clinics, first emergency responders, medical wards, nursing homes, dental clinics, and pharmacies. Two hundred forty health workers filled the entire survey, resulting in a response rate of 59.7%.

The healthcare workers reported their demographic characteristics such as actual age, gender, number of children, education level, daily exercise hours, and number of office days in the past week. We also asked whether they were temporary staff or were redeployed from their usual positions (i.e., from non-ICU to ICU) to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. The outcome variables included healthcare workers’ job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention.

Job Satisfaction

We measured healthcare workers’ job satisfaction by a five-item scale (Brayfield and Rothe 1951; Montazeri et al. 2011). These five items were scored on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale. Sample items include “I find real enjoyment in my work” and “most days I am enthusiastic about my work.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80.

Life Satisfaction

The respondents reported using the five-item scale of Satisfaction with Life (SWL) (Diener et al. 1985). These five items were scored on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale. Sample items include “in most ways my life is close to my ideal” and “the conditions of my life are excellent.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81.

Turnover Intention

We used the 5-point scale to measure healthcare workers’ turnover intention (Cammann et al. 1979). The three items were scored on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert scale. Sample items include “I often think about quitting my job with my present organization” and “it is very possible that I will look for a new job next year.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

We used Stata 16.0 to summarize the variables and to identify the predictors of job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention with a 95% confidence level.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Table 1 shows that 72.9% of the 240 healthcare workers were female, and 8.3% were younger than 29 years old, 29.2% were between 30 and 39 years, 57.5% were between 40 and 59 years, and 5.0% were 60 years or older. Most participants (91.7%) had an undergraduate degree or higher. Less than a third (30.8%) were temporary staffs, and 10.8% had been redeployed to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. Finally, 6.7% of participants worked in healthcare facilities 7 days in the past week, 4.2% worked 6 days, 14.2% worked 5 days, and 71.3% worked between 1 and 4 days, and 3.8% worked zero days. Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations.

Predictors of Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention

First, healthcare workers’ office days predicted their job satisfaction but the relationship depended on their age (b = 0.01; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.02; P = .004). Margin analysis showed that office days negatively predicted job satisfaction for the young healthcare workers (e.g., at 25 years old: b = − 0.21; 95% CI: − 0.36 to − 0.60; P = .006). On the contrary, office days positively predicted job satisfaction for the older workers (e.g., at 65 years old: b = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.44; P = .009).

Second, office days predicted workers’ life satisfaction overall, and the relationship also depended on their age (b = 0.01; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.02; P = .04). In particular, the number of office days was positively associated with life satisfaction among the older workers (e.g., at 65 years old: b = 0.22; 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.44; P = .04) but was marginally negatively associated with life satisfaction among the younger workers (e.g., at 25 years old: b = − 0.15; 95% CI: − 0.32 to 0.03; P = .09). In addition, job redeployment (b = − 0.51; 95% CI: − 0.97 to − 0.05; P = .03) and daily exercise hours in the past week (b = 0.07; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.14; P = .04) both predicted life satisfaction.

Lastly, healthcare workers’ office days predicted their turnover intention, and the relationship similarly depended on their age (b = − 0.01; 95% CI: − 0.01 to 0.00; P = .05). In particular, the number of office days was positively associated with turnover intention among the younger workers (e.g., at 25 years old: b = 0.16; 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.29; P = .03) but not the older healthcare workers.

These results were shown in a forest plot (Dai et al. 2020; Graf-Vlachy et al. 2020) in Fig. 1.

Discussion

Healthcare workers are especially critical in the COVID-19 pandemic (Ni et al. 2020). This study presents the first attempt to identify which healthcare workers have more or less job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Several covariates, which were significant predictors of mental health and well-being in healthcare workers in earlier studies, were not significant in our study. For instance, age and gender predicted mental health and well-being among healthcare workers in China (Lai et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2020) and in Iran (Kaveh et al. 2020), and in Spain (age only) (Romero et al. 2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, neither age nor gender predicted outcomes in this study. In addition, education was found to be a predictor of mental health of health staff in studies in China (Li et al. 2020; Liu et al. in press) but not in another study in Iran (Zhang et al. 2020a). Education was not a significant predictor of satisfaction or turnover intention in our sample. These findings support that the predictors of healthcare staff’s job-related variables and well-being during a pandemic vary across countries (Zhang et al. 2020a).

Moreover, this study identified several unique risk factors including weekly office days. Importantly, the number of office days predicted job satisfaction positively for the older healthcare staff, but negatively for the younger staff. Similar patterns existed on the outcome variables of life satisfaction, and turnover intention. These findings suggest that healthcare organizations need to pay attention to younger workers working many days a week and older workers with fewer office days.

While it can be necessary to redeploy workers or hire temporary staff to deal with the COVID-19 crisis, those workers who were redeployed were less satisfied with their lives. Hence, hospitals may need to better support those redeployed healthcare workers. It is also worth noting that the temporary healthcare staff did not significantly differ from regular staff on job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention.

This study has some limitations. First, as data collection is challenging during the COVID-19 crisis, particularly for busy healthcare staff, we used convenience sampling. Second, to our best knowledge, this is the first study that has examined several job characteristics, such as office days, temporary staff, and job redeployment, as predictors for healthcare workers’ job-related outcomes under COVID-19. Such practices differ across countries and healthcare systems (Jahanshahi et al. 2020), and future studies may test these factors.

Protecting and retaining healthcare workers is paramount during a pandemic. This study demonstrates that healthcare workers’ number of office days matters to their job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intention. However, the number of office days carries different impacts on younger and older workers. We call for more studies on healthcare workers from the perspective of their ongoing working characteristics under the COVID-19 pandemic.

Change history

01 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00502-5

References

Alvarez-Risco, A., Mejia, C. R., Delgado-Zegarra, J., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., Arce-Esquivel, A. A., Valladares-Garrido, M. J., et al. (2020). The Peru approach against the COVID-19 infodemic: Insights and strategies. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(2), 583–586. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0536.

Arigho-Stiles O. (2020). Covid-19 in Bolivia fuels political crisis. Discover Society. https://discoversociety.org/2020/04/03/covid-19-in-bolivia-fuels-political-crisis/. Accessed 3 Jul 2020.

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35, 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055617.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Chen, X., Zhang, S. X., Jahanshahi, A. A., Alvarez-Risco, A., Dai, H., Li, J., & Ibarra, V. G. (2020). Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(3), e20737. https://doi.org/10.2196/20737.

Cloherty, M. (2020). Sibley Memorial Hospital nurse quits over ‘lack of protection.’ WTOP News. https://wtop.com/coronavirus/2020/03/sibley-memorial-hospital-nurse-quits-over-lack-of-protection/. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Dai, H., Zhang, S. X., Looi, K. H., Su, R., & Li, J. (2020). Perception of health conditions and test availability as predictors of adults’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of adults in Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155498.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 47, 71–75.

Galdos, G. (Producer). (2020). Bodies left in streets of Guayaquil as Ecuador struggles with coronavirus. Channel 4 News. https://www.channel4.com/news/bodies-left-in-streets-of-guayaquil-as-ecuador-struggles-with-coronavirus. Accessed 3 Jul 2020.

Graf-Vlachy, L., Sun, S., & Zhang, S. X. (2020). Predictors of managers’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 17(15), 5498.

Jahanshahi, A. A., Dinani, M. M., Madavani, A. N., Li, J., & Zhang, S. X. (2020). The distress of Iranian adults during the Covid-19 pandemic – More distressed than the Chinese and with different predictors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 124–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.081.

Kaveh, M., Davari-tanha, F., Varaei, S., Shirali, E., Shokouhi, N., Nazemi, P., Ghajarzadeh, M., Feizabad, E., & Ashraf, M. A. (2020). Anxiety levels among Iranian health care workers during the COVID-19 surge: A cross-sectional study. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.02.20089045.

Kirsch, T. (2020). What happens if health-care workers stop showing up? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/were-failing-doctors/608662/. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Labrague, L. J., & de los Santos, J. (2020). Fear of Covid-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13168.

Lai, J., Ma, S., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Hu, J., Wei, N., Wu, J., du, H., Chen, T., Li, R., Tan, H., Kang, L., Yao, L., Huang, M., Wang, H., Wang, G., Liu, Z., & Hu, S. (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

Laing, A., & Ramos, D. (2020). Bolivia coronavirus patient turned away from hospitals; election rallies suspended. U.S.News.

Li, X., Yu, H., Bian, G., Hu, Z., Liu, X., Zhou, Q., Yu, C., Wu, X., Yuan, T. F., & Zhou, D. (2020). Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlates of insomnia in volunteer and at home medical staff during the COVID-19. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 140–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.008.

Liang, Y., Chen, M., Zheng, X., & Liu, J. (2020). Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 133(6), 110102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110102.

Liu, D., Ren, Y., Yan, F., Li, Y., Xu, X., Yu, X., Qu, W., Wang, Z., Tian, B., Yang, F., Yao, Y., Tan, Y., Jiang, R., & Tan, S. (in press). Psychological impact and predisposing factors of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on general public in China. Lancet Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3551415.

Montazeri, A., Vahdaninia, M., Mousavi, S. J., Asadi-Lari, M., Omidvari, S., & Tavousi, M. (2011). The 12-item medical outcomes study short form health survey version 2.0 (SF-12v2): A population-based validation study from Tehran, Iran. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-12.

Ni, M. Y., Yang, L., Leung, C. M. C., Li, N., Yao, X., Wang, Y., . . . Liao, Q. (2020). Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health, 7(5), e19009. https://doi.org/10.2196/19009.

O'Connor, C., & Murphy, M. (2020). Going viral: Doctors must tackle fake news in the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ, 369(m1587). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1587.

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026.

Requena, M. A. (2020). Bolivian doctors and nurses protest for lack of supplies (Spanish). CNN in Spanish. https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/video/doctores-enfermeras-bolivianos-protestan-falta-insumos-medicos-suministros-bolivia-panorama-mundial-cnnee/. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Romero, C.-S., Catalá, J., Delgado, C., Ferrer, C., Errando, C., Iftimi, A., Benito, A., De Andres, J., & Otero, M. (2020). COVID-19 Psychological Impact in 3109 Healthcare workers in Spain: The PSIMCOV Group. Psychological Medicine, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001671.

Tang, P. M., Zhang, S. X., Li, C. H., & Wei, F. (2020). Geographical identification of the vulnerable groups during COVID-19 crisis: Psychological typhoon eye theory and its boundary conditions. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences., 74, 562–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13114.

Yáñez, J. A., Jahanshahi, A. A., Alvarez-Risco, A., Li, J., & Zhang, S. X. (2020). Anxiety, distress, and turnover intention of healthcare workers in Peru by their distance to the epicenter during the COVID-19 crisis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene., 103, 1614–1620. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0800.

Yang, L., Yin, J., Wang, D., Rahman, A., & Li, X. (2020). Urgent need to develop evidence-based self-help interventions for mental health of healthcare workers in COVID- 19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001385.

Zhang, S. X., Liu, J., Jahanshahi, A. A., Nawaser, K., Yousefi, A., Li, J., & Sun, S. (2020a). At the height of the storm: Healthcare staff’s health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 144–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.010.

Zhang, S. X., Wang, Y., Rauch, A., & Wei, F. (2020b). Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research, 2020(288), 112958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958.

Funding

This research was funded by the MOE Project of Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at Universities (16JJD630005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Stephen X. Zhang; Formal analysis: Stephen X. Zhang and Jiyao Chen; Investigation: Stephen X. Zhang, Asghar Afshar Jahanshahi, Aldo Alvarez-Risco and Ross Mary Patty-Tito; Methodology: Stephen X. Zhang, Asghar Afshar Jahanshahi and Aldo Alvarez-Risco; Resources: Jizhen Li; Visualization: Jiyao Chen and Huiyang Dai; Writing – original draft: Stephen X. Zhang and Jiyao Chen; Writing – review & editing: Stephen X. Zhang, Jiyao Chen and Huiyang Dai; Supervision, Stephen X. Zhang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S.X., Chen, J., Afshar Jahanshahi, A. et al. Succumbing to the COVID-19 Pandemic—Healthcare Workers Not Satisfied and Intend to Leave Their Jobs. Int J Ment Health Addiction 20, 956–965 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00418-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00418-6