Abstract

The early Cenomanian crippsi Event comprises a 1–3-m-thick interval characterised by mass occurrences of the early Cenomanian inoceramid Gnesioceramus crippsi, identified in the uppermost Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone (lower lower Cenomanian Mantelliceras mantelli Zone), below an interregional sequence boundary (SB Ce 1). At Lüneburg, the event is characterised by densely packed, very large, disc-like valves of G. crippsi. Taphonomy as well as bio- and microfacies suggest an event formation in a deeper shelf setting below the storm-wave base as primary biogenic concentration, the inoceramids living as recumbent forms on a soft substrate in dense populations. When tracked between basins, the stratigraphic pattern of the crippsi Event suggests a moderately prolonged phase (< 100 kyr) of increased shell production with rapid deposition aiding in preserving the shell-rich event strata. Towards the basin margins, it grades into storm wave-reworked bioclastic concentrations. The crippsi Event formed by an interregional population bloom and provides, as an proliferation epibole, an important marker for intra- and interbasinal correlation. The first record of G. mowriensis within the crippsi Event at Lüneburg, hitherto endemic to the US Western Interior Seaway, and the occurrence of the ammonite Metengonoceras teigenense, likewise an endemic North American faunal element, from the level of the crippsi Event in northern France indicate faunal exchange between the New and Old worlds during the early Cenomanian. This faunal dispersal and contemporaneous occurrence of warm-water biofacies in Western Europe during the early Cenomanian is explained by the existence of a perpetual NE-directed current transporting warm surface waters from the Gulf of Mexico towards Europe. The occurrence of short-lived M. teigenense in France allows for the calibration of the uppermost schlueteri Subzone of the mantelli Zone in Europe to the lowermost Neogastroplites muelleri Zone in North America and to assign an age of ~ 98.6–98.7 Ma to the crippsi Event.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Widespread beds or thin packages of strata that either characterised by unusual fossils or concentrations of usually common faunal elements are a specific feature of Upper Cretaceous epicontinental strata in NW Europe and beyond (e.g. Ernst et al. 1983, 1996; Dahmer and Ernst 1986; Lehmann 1999; Wiese et al. 2004; Wilmsen and Voigt 2006; Wilmsen et al. 2007; Wilmsen 2008; Wiese et al. 2009; Amédro et al. 2012; Nagm 2019). Such palaeontological events, termed bioevents by Ernst et al. (1983), form important marker beds that have widely been used for correlation (e.g. Bower and Farmery 1910) even if the processes that governed their formation often remained obscure. However, it was not before the end of the last century that bioevents became the focus of more detailed and integrated research (Ernst et al. 1983; Kauffman and Hart 1995; Brett and Baird 1997). Bioevents were recognised to occur at local, regional, and global scales and are inferred to reflect short- to intermediate-term (hours to tens-of-thousands of years) ecologic, evolutionary, and/or palaeo(bio)geographic responses of biota to fluctuations of environmental parameters. Sea-level changes influence a number of important (abiotic) environmental factors in a predictable way (e.g. water depth and energy, sedimentation rate, temperature, light availability) and have been demonstrated to be an important part of bioevent formation (e.g. Brett 1995; Ernst et al. 1996; Holland 2000, 2001; Wilmsen 2012). Preferential positions for bioevent formation in a depositional sequence are the early transgressive, maximum flooding and late highstand phases (Wilmsen 2012). Late Cretaceous early transgressive (e.g. Wilmsen and Voigt 2006; Wilmsen et al. 2007) and maximum flooding bioevents (e.g. Wilmsen 2008; Nagm 2019) have already been detailed but a late highstand bioevent still awaits comprehensive palaeontologic, sedimentologic, and taphonomic dissection. Thus, the crippsi Event is studied herein based on excellently preserved inoceramid material from Lüneburg (northern Germany). Unfortunately, no detailed section exists from this locality and the site is not accessible anymore. However, the finds from Lüneburg can be integrated into the detailed stratigraphic framework of the lower Cenomanian and (inter-)regional correlations based on bio- and event stratigraphic considerations.

Geological and stratigraphic setting

The Triassic–Cenozoic succession brought to surface in Lüneburg due to halokinetic movements of Zechstein evaporites around the so-called Kalkberg (a central gypsum cap-rock of the Lüneburg salt dome) is a classical site for Cretaceous palaeontology and stratigraphy (e.g. von Strombeck 1863; Stolley 1896; Wollemann 1902; Heinz 1926; Schmid 1962, 1963). The Cretaceous succession is ca. 450 m thick, starting with a thin (ca. 23 m) middle-upper Albian argillaceous-marly unit (“upper Gault” of Lüneburg; Ernst 1921) overlying Upper Triassic “Steinmergelkeuper” (Arnstadt Formation), followed by an Upper Cretaceous succession comprising all substages up to the lower Maastrichtian (Schmid 1962). However, due to complex halokinetic faulting, the succession is strongly tectonized (e.g. Stümke 1905), and this is the main reason for the lack of detailed measured sections from this locality. After centuries of salt, gypsum, and chalk mining, the extensive quarries were abandoned in the mid-twentieth century and the Zeltberg site (from which the finds reported in this study derive) was transformed into a recreational area including a lake (the so-called Kreidebergsee; for more information on the Kalkberg in Lüneburg, see Stein 1992).

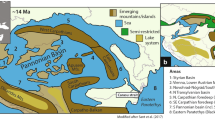

Palaeogeography

The former Zeltberg quarry in Lüneburg (Fig. 1a, c) is located north of the centre of the town of Lüneburg, ca. 40 km southeast of Hamburg (northern Germany). During Cenomanian times, it occupied a rather distal position on the north German shelf that was characterised by a general transgression from north to south/southeast. In the course of transgression, sediments of the roughly coast-parallel facies belts (inner shelf greensands and marls, mid-shelf marl-limestone alternations and outer shelf chalk-like limestone) were superimposed, reflecting the overall retrogradational stratigraphic stacking patterns (Wilmsen et al. 2005). In the early Cenomanian, the coastline was already far south of Lüneburg und hemipelagic to pelagic deposition of marl-limestone alternations of the Baddeckenstedt Formation and chalky limestones of the Brochterbeck Formation prevailed over much of the middle and outer shelf (Fig. 1a, b). Based on the chalky nature of the rocks and the near-absence of marly interbeds (Fig. 2), the strata containing the crippsi Event in Lüneburg are assigned to the Brochterbeck Formation. This is the stratigraphically deepest record of this formation in northern Germany (cf. Niebuhr et al. 2007) and highlights the time-transgressive character of the lithostratigraphic units.

Geological setting and locality details. a Palaeogeography of the north German shelf (base map modified from Hiss 1995) during the early Cenomanian with indication of the principal shelf facies zones and the location of Lüneburg (red asterisk). Reference sections (green asterisks): 1 Halle-Ascheloh; 2 Staffhorst shaft; 3 Hannover-Anderten; 4 Konrad-101 borehole. b Integrated stratigraphic framework of the lower Cenomanian in northern Germany showing litho-, bio-, event, and sequence stratigraphic details (compiled after Ernst et al. 1983; Wilmsen 2003, 2012; Wright and Kennedy 2017). c Locality details of the crippsi Event in the former Zeltberg quarry in Lüneburg (now Kreidebergsee recreational area)

Stratigraphy

The Cenomanian strata of northern Germany have been stratigraphically dated and correlated with an integrated approach since many decades (e.g. Ernst et al. 1979). Of utmost importance are macrofossil biostratigraphy, bioevents, and sequence stratigraphy (cf. Fig. 1b).

Macrofossil biostratigraphy

The key groups for macrofossil biostratigraphy in lower Cenomanian strata of northwest Europe are ammonites and inoceramid bivalves. The substage is commonly subdivided into two ammonite biozones, i.e. a lower (lowest occurrence) interval zone of Mantelliceras mantelli and an upper total range zone of M. dixoni (see recent synopsis by Wright and Kennedy 2017; Fig. 1b). These two zones correspond to the interval zones of Gnesioceramus crippsi and Inoceramus virgatus, respectively (e.g. Tröger 1989). The M. mantelli Zone can be further subdivided into three subzones, i.e. in ascending order, the Neostlingoceras carcitanense, Sharpeiceras schlueteri, and M. saxbii subzones (Gale and Friedrich 1989; Gale 1995; Wright and Kennedy 2017; Fig. 1b). The stratigraphic level in question falls into the upper part of the mid-M. mantelli zonal Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone which is equivalent to a mid-Gnesioceramus crippsi zonal position.

Early Cenomanian bioevents

Ultimus/Aucellina Event:

This event is characteriased by in places abundant specimens of the belemnite Neohibolites ultimus (d’Orbigny) and the small bivalve Aucellina associated with phosphorite and glauconite concentrations (Ernst et al. 1983). Its stratigraphic position is in the lower part of the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone (Neostlingoceras carcitanense Subzone). The event marks the onset of the Cenomanian transgression (ultimus/Aucellina transgression) and thus corresponds to an early transgressive bioevent (Fig. 1b). It often rests unconformably with a basal hiatus on upper Albian strata; only in central basinal positions, it overlies argillaceous lowstand deposits (the Bemerode Member of the Herbram Formation) that straddle the Albian–Cenomanian boundary (Bornemann et al. 2017; Fig. 1b).

Crippsi Event:

This event, introduced by Tröger (1995) for a stratigraphic interval in the middle part of the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone (upper Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone; Fig. 1b), is rich in inoceramid bivales of G. ex gr. crippsi (Mantell) (see also Gale and Friedrich 1989 and Gale 1995). In Lüneburg, it is characterised by densely packed shell accumulations (float- to rudstones) predominantly consisting of large, often isolated inoceramid valves. The crippsi Event is interpreted as a late highstand bioevent (Wilmsen 2012), based on its taphonomic signature and position below sequence boundary SB Ce 1 in all sections studied so far (Fig. 1a, b and see below).

Mariella Event:

This event, broadly corresponding to an acme of large turrilitid ammonites (Hypoturrilites and Mariella) in the lowermost part of the M. dixoni Zone (Kaplan and Best 1985), was detailed by Ernst and Rehfeld (1997) in the Baddeckenstedt section near Salzgitter, comprising two fairly coarse-grained limestone beds rich in siliceous sponges, often fragmentary inoceramid valves, and ammonites (their sponge bed/Mariella Event). Taphonomic phenomena such as corrosion and glauconitization suggest condensation during the formation of the event bed (Ernst and Wood 1995), and its position shortly above sequence boundary SB Ce 2 characterises it as an early transgressive bioevent (Wilmsen 2012; Fig. 1b).

Schloenbachia/virgatus Event: (Ernst et al. 1983)

This event comprises an interval of five marl-limestone couplets with high carbonate content in the mid-M. dixoni Zone, characterised by an abundance of commonly double-valved Inoceramus ex gr. virgatus Schlüter and Schloenbachia varians (J. Sowerby) (see Wilmsen 2008). The accompanying fauna is of low diversity and consists of rare sponges, small brachiopods, and irregular echinoids. It is a typical example of a maximum flooding bioevent (Wilmsen 2008, 2012; Fig. 1b).

Orbirhynchia/Schloenbachia Event: (Ernst et al. 1983)

This mid-M. dixoni zonal event (Fig. 1b) is characterised by the common occurrence of the small rhynchonellid brachiopod Orbirhynchia mantelliana (J. de C. Sowerby) accompanied by likewise common S. varians and a moderately diverse assemblage of terebratulid brachiopods, sponges, heteromorph ammonites, gastropods as well as inoceramid and non-inoceramid bivalves. It can be correlated from the northern German across the Anglo-Paris Basin into the Cleveland Basin (“lower Orbirhynchia band” of Jeans 1980; e.g. Gale 1995) and is regarded as a maximum flooding bioevent (Wilmsen 2012).

Sequence stratigraphy

The early Cenomanian was a strongly transgressive time interval characterised by three onlap pulses that led to the retrogradational stacking of three depositional sequences (e.g. Robaszynski et al. 1998; Wilmsen 2003; Janetschke et al. 2015). The bounding unconformities are sequence boundaries SB Ce 1 to SB Ce 3 (Fig. 1b). SB Ce 1 and SB Ce 2 have been identified in the middle and at the summit of the M. mantelli Zone, SB Ce 2 corresponding to the “Sub-dixoni Erosional Surface” (SdES) of Wright and Kennedy (2017), while SB Ce 3 is placed close to the top of the M. dixoni Zone, slightly below the base of the middle Cenomanian (e.g. Wilmsen 2007; Fig. 1b). In northern Germany, the crippsi Event has been documented to occur in the upper (late highstand) part of Cenomanian depositional sequence DS Ce 1, just below SB Ce 1 (e.g. Niebuhr et al. 2001; Wilmsen 2003, 2012; Richardt 2010; cf. Fig. 1b). In Lüneburg, the sequence stratigraphic position of the crippsi Event cannot be specified due to the absence of a detailed log and the inaccessibility of the strata today.

Material and methods

The material studied herein is stored in the palaeozoological collection of the Senckenberg Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden (SNSD), Department Museum für Mineralogie und Geologie (MMG, repository prefix number MMG: NsK), and the collection of DS in Brietlingen (repository number: DSB plus running number). The latter material will be transferred to the collections of the SNSD-MMG at a later stage. The material was collected from a shallow (maximum 30-cm-deep) excavation of ca. 2 × 1.8-m size conducted discontinuously in winter months during 1980–1994. Biometric standard measurements of inoceramid bivalves, taken with a Vernier caliper, comprise height (h) and length (l) of the shell as well as observations on the sculpture (number, size, and form of ribs) and the course of the growth axis (for terminology and measured parameters, see Fig. 3). For the higher rank systematics of the Bivalvia, we refer to Carter et al. (2011). A thin section of the host strata was prepared on a Logitech preparation line using a LP50 lapping and polishing jig with a PLJ7 lapping jig and a GTS-1 thin-section saw. Microfacies was observed with a Leica M125 stereo-microscope equipped with a Leica DFC 420 digital camera placed in the optical path.

Results

Observations on litho- and biofacies as well as palaeontological analyses (taphonomy and systematic descriptions) form the data basis of this study.

Lithofacies

The lithofacies of the event bed in Lüneburg is dominated by fine-grained, light-grey chalky limestones (Fig. 2) which form the matrix for the fine-to-coarse-grained shell material (predominantly inoceramid valves and debris, up to 160 mm/100 mm in height/length, respectively). Thin-section analyses characterise the matrix as fine-grained calcisphere-bearing wackestone with subordinate content of predominantly non-keeled planktic foraminifers and microbioclasts (mainly isolated prisms of disintegrated inoceramid shells; Fig. 4a). Nevertheless, due to the variably high content of inoceramid shell material larger than 2 mm and the density of packing, the rocks of the event partly have to be classified as bioclastic inoceramid float- to rudstones (Fig. 4c, e). Chambers of calcispheres (calcareous cysts of dinoflagellates, i.e. c-dinocysts) and planktic foraminifera are partly filled with pyrite; framboidal pyrite of variable size also occurs scattered in the matrix (Fig. 4b).

Microfacies and taphonomy of the early Cenomanian crippsi Event at the former Zeltberg quarry, Lüneburg. a Microbioclastic calcisphere wackestone with planktic foraminifers and isolated inceramid prisms (thin section prepared from the matrix of MMG: NsK 1274). b Calcisphere wackestone with rare inceramid prisms; note the dark pyritic filling of calcispheres and the dispersed framboidal pyrite in the matrix (thin section prepared from the matrix of MMG: NsK 1274). c Shell pavement of large Gnesioceramus crippsi (Mantell, 1822), mostly in convex-up position; note the coarse-grained bioclastic fabric between the shells, the disarticulated hinge in upper centre, and the overall very thin shell thickness (sample DSB-1, scale in mm). d Double-valved specimen of Gnesioceramus crippsi (Mantell, 1822) in butterfly position (sample DSB-2). e Concentration of isolated hinges on a limestone slab (sample DSB-3, scale in mm)

Biofacies

The faunal assemblage of the crippsi Event in Lüneburg is in abundance completely dominated by inoceramid bivalves, i.e. Gnesioceramus crippsi, accompanied by a few specimens of G. mowriensis. However, apart from the ubiquitous inoceramids, the following invertebrate and vertebrate taxa have been identified (the number of the benthic taxa is given in [square brackets]):

Ammonites: Mantelliceras mantelli (J. Sowerby), Mantelliceras cf. cantianum Spath, Mantelliceras sp., large Austiniceras austeni (Sharpe), Schloenbachia varians (J. Sowerby), Hypoturrilites tuberculatus (Bosc) and large Mariella sp.

Bivalves: Euthymipecten beaveri (J. Sowerby), Limea granulata (Nilsson), Limaria elongata (J. de C. Sowerby), Teredina amphisbaena (Goldfuss), Plicatula inflata J. de C. Sowerby and small oysters (Hyotissa sp.) [ca. 60 specimens]

Gastropods: Bathrotomaria sp. [a single specimen]

Echinoids: Cardiaster granulosus (Goldfuss), Holaster sp., Salenia sp. [19 specimens]

Arthropods: claws of decapod crustaceans (Protocallianassa sp. and an unidentified taxon) [two specimens] and Palaega carteri (Woodward) [four specimens]

Shark teeth: Hexanchus gracilis (Davis), Cretolamna appendiculata (Agassiz), Scapanorhynchus rhaphiodon (Agassiz)

Additionally, brachiopods (three taxa, 22 specimens), serpulids (Rotulispira? sp., 21 specimens), bryozoans (five taxa, 22 specimens), starfish ossicles, and the trace fossil Lepidenteron mantelli (Geinitz) have been recorded.

Taphonomy

The taphonomic observations are focused on the inoceramids within the crippsi Event. A brief account on the large G. crippsi show that most valves are disarticulated and that the large, discoidal shells are often imbricated, forming true inoceramid pavements (Fig. 4c). Most valves have been found to occur in convex-up position (ca. 80%, n = 56) albeit the flat, sparsely domed shape of the shell certainly restricted overturning into the stable position. Fragments of variable size occur scattered or are concentrated in lenses between the shells (Fig. 4c). The thick and stable ligament ridges may have been concentrated, too (Fig. 4e). On the other hand, a few specimens occur in butterfly position with the right and left valves associated and facing each other with the two umbos (Fig. 4d).

Systematic palaeontology

Class Bivalvia Linnaeus, 1758

Subclass Pteriomorphia Beurlen, 1944

Order Pterioida Newell, 1965

Family Inoceramidae Giebel, 1852

Genus Gnesioceramus Heinz, 1932

Type species: Inoceramus anglicus Woods, 1911 (p. 264, pl. 45, figs. 8–10, text-fig. 29), by subsequent designation of Pokhialainen (1985a, p. 32; note that the genus is erroneously spelled “Gneisioceramus” therein).

Remarks: This genus, originally proposed by Heinz (1932, p. 6) for the common Cenomanian species Inoceramus crippsi Mantell characterised by coarse commarginal growth folds (“Anwachsreifen”), was long-time neglected until Pokhialainen (1985a, b) described the generic characteristics in more detail and formally designated I. anglicus as the type species of the genus (see Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016 for additional information).

Gnesioceramus crippsi (Mantell, 1822)

*1822 Inoceramus crippsii, Mantell, p. 133, pl. 27, fig. 11

1863 Inoceramus striatus Mant. – von Strombeck, p. 108

1902 Inoceramus orbicularis Münster – Wollemann, p. 65

1909 Inoceramus crippsi Mantell – Boehm, p. 41, pls 9, 10, pl. 11, fig. 1 [with early synonymy]

1911 Inoceramus crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Woods, p. 273, pl. 48, figs. 2 and 3, text-figs. 33 and 34

non 1956 Inoceramus Crippsi, Mantell – Kilpady and Kulkarni, p. 2, pl. 1 figs. 1 and 2

1962 Inoceramus crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Bräutigam, p. 188, pl. 1, figs. 1 and 2

1967 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mant., 1822 – Tröger, p. 24, pl. 2, figs. 4 and 5

1982 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Keller, p. 44, pl. 1, fig. 5 [see for additional synonymy]

1987 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Cieśliński, p. 37, text-fig. 19a–c

1987 Inoceramus crippsi orbicularis Münster, 1836 – Cieśliński, p. 39, text-fig. 20a, b

1987 Inoceramus crippsi mogilensis subsp. n., Cieśliński, p. 42, text-fig. 25

2001 “Inoceramus” crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Wilmsen et al., p. 129, pl. 1, fig. 1 [with additional synonymy]

2002 “Inoceramus” ex gr. crippsi Mantell – Wilmsen and Niebuhr, text-fig. 5

2009 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Tröger et al., p. 62, figs. 3a–c and 4a

2010 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell – Wilmsen and Niebuhr, p. 275, figs. 4h and 5

2010 “Inoceramus” crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Richardt, p. 51, pl. 1, fig. 1, text-fig. 11

2012 “Inoceramus” crippsi – Wilmsen, text-fig. 6d

2012 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Amédro et al., pl. 1, pl. 2, figs. 1–3

2013 Inoceramus crippsi crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Schneider et al., p. 570, text-fig. 10d [with further synonymy]

2019 Inoceramus crippsi – Püttmann et al., text-fig. 3n

2019 Inoceramus crippsi Mantell, 1822 – Kaplan et al., p. 29, text-fig. 4

Material: 155 specimens, either isolated or scattered on a several rock slabs of variable size (retrieved from a shallow excavation of 2 × 1.8 m size)

Description: The shells are equivalved, inequilateral, subcircular in outline, and only weakly inflated. Maximum length and height are 152 mm and ~ 105 mm, respectively. The umbo is not extending above the hinge line, and the ligamental area is relatively wide. Well-rounded small rugae appear a few millimeters from the umbo and develop into coarse, sharp-edged concentric rugae in adults. The rugae are up to 3 mm high and asymmetric, i.e. the slope directed to the umbo is shallower compared with the ventrally directed one. The inter-rugae spaces are ca. 3 mm wide on the juvenile and 10 mm wide on the adult part of the shell. Up to a height of ca. 75 mm, 2–4 secondary ribs may be developed in the depressions between the rugae. The ligament is long and massive, with smooth transition to the posterior margin. Compared with the relatively large size of many specimens, the thickness of the shell is quite low (≤ 1 mm).

Remarks: Gnesioceramus crippsi is a well-known early Cenomanian inoceramid taxon that ranges, as a rarity, up into the middle Cenomanian (e.g. Tröger 1989; Wiedmann et al. 1989). It is readily characterised by a subcircular growth trace, regularly developed rugae, an oblique and slightly convex growth axis, and a weakly inflated shell with a massive ligamental plate (e.g. Wilmsen et al. 2001). The rugae continue across the shell without weakening, except on the posterior wing. Extraordinary is the in part very large size of the specimens compared with other records of G. crippsi, reaching > 150 mm in height and > 100 mm in length. In conjunction with the near-absence of shell convexity, the specimens tend to have a disc-like appearance. This feature, along with the flange-like anterior margin and the distinctively triangular ligament plate with its closely spaced and vertically elongated ligamental pits cause a certain resemblance of Gnesioceramus crippsi to the much younger (mid-to-late Late Cretaceous) genus Platyceramus (Wilmsen et al., 2001). Similarily, Kauffman and Powell in Kauffman et al. (1977, pp. 84–86) discussed a relationship to the genus Mytiloides and provisionally referred this species to Mytiloides? crippsi. Contemporaneous Gnesioceramus hoppenstedtensis have a dorsoventrally elongate shell, a more or less straight growth axis, a much thinner shell, and more irregularly developed rugae (see below). Several of the subspecies of I. crippsi described by Cieśliński (1987) can be accommodated in G. crippsi. However, the giant specimen assigned to Inoceramus crippsi by Kilpady and Kulkarni (1956) from the Cretaceous of Trichinopoly (India) is doubtful as it is very large (> 0.5 m in height), has strongly inflated, convex shells and only very few (five to seven) and very coarse concentric folds. Its exact stratigraphic position is also unclear, and it may rather be a representative of the Turonian lamarcki group or an even younger species. G. crippsi has been noted from the lower Cenomanian (= varians Pläner) of Lüneburg already in early studies (von Strombeck 1863; Wollemann 1902), albeit under species names that have subsequently been synonymized with Mantell’s species (cf. Boehm 1909).

Occurrence: Gnesioceramus crippsi is a very widespread form that ranges from the lower Cenomanian into the lower middle Cenomanian (Keller 1982; Kaplan et al. 1984; Wiedmann et al. 1989; Tröger 1989, 2009). In the type area in southern England, this taxon characterises the Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone of the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone, in which it is very common, dominating the inoceramid assemblage.

Gnesioceramus mowriensis Walaszczyk and Cobban, 2016

(Fig. 8)

2016 Gnesioceramus mowriensis sp. nov., Walaszczyk and Cobban, p. 53, text-figs. 17–19

Material: Eight specimens, mostly isolated and partly fragmentary valves

Description: Small-to-medium-sized form with equivalved and inequilateral, only weakly inflated shells, higher than long (maximum measured height 53 mm, length ~ 42 mm; Fig. 8). The apical angle measures ca. 70°; the growth axis is almost straight. The anterior margin is straight to slightly convex, and the ventral margin broadly rounded; posterior margin long and straight. The ligamental area is poorly preserved but shows a thickened hinge line; otherwise, the shell is very thin. The regularly developed ornament consists of evenly spaced, symmetric, and rounded commarginal ribs and narrow interspaces (ca. 50 ribs at a height of 50 mm, rib distance 1.8 mm on the adult shell). Following a faint, regular increase of rib and interspace dimensions in the juvenile stage, the ornament remains almost constant during the later ontogeny.

Gnesioceramus mowriensis Walaszczyk and Cobban, 2016 from the early Cenomanian crippsi Event of the former Zeltberg quarry in Lüneburg. a Several isolated valves scattered on a limestone slab (sample MMG: NsK 1274). b Specimen MMG: NsK 1275 (left valve). c Specimen DSB-7 (right valve). d Several isolated valves scattered on a limestone slab (sample DSB-8)

Remarks: Introduced by Walaszczyk and Cobban (2016), G. mowriensis is very similar to the late Albian G. anglicus (Woods). It differs from Woods’ species in a more subtrapezoidal outline, a finer ornament, and a shorter length of the anterior margin. Inoceramus tenuis Mantell has a straight to slightly concave anterior margin, a concave growth axis, is much more inflated, and is less regularly ribbed (see Woods 1911, p. 271, pl. 48, fig. 1, text-figs. 31, 32).

Occurrence: Gnesioceramus mowriensis is so far only known from the mid-lower Cenomanian of the US Western Interior Seaway (Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana) where it ranges from the Neogastroplites cornutus up to the N. americanus ammonite Zone (Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016). The stratigraphic position is equivalent to the specimens from the crippsi Event at Lüneburg. This is the first record of G. mowriensis from outside northern America.

Discussion

Even if no detailed measured section exists for the (lower) Cenomanian of Lüneburg and the material was retrieved from a shallow excavation, the stratigraphic position of the strata with super-abundant G. crippsi can be precisely calibrated. In its type area in southern England, this taxon particularly characterises the Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone in the middle of the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone (cf. Wright and Kennedy 2017), in which it is very common, dominating the inoceramid assemblage (Wilmsen et al. 2001; see also Gale and Friedrich 1989 for Folkstone). A position within the lower lower Cenomanian M. mantelli Zone is ascertained by the index species from the layers with super-abundant G. crippsi at Lüneburg. The co-occurrence of (rather inflated) M. mantelli and M. cantianum with common Hypoturrilites more specifically supports a classification into the S. schlueteri Subzone (see Gale and Friedrich 1989; Gale 1995). Gnesioceramus mowriensis, so far only known from the mid-lower Cenomanian of the US Western Interior Seaway, ranges from the Neogastroplites cornutus up to the N. americanus ammonite Zone (Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016), corresponding to the middle and upper M. mantelli Zone as well as the lower M. dixoni Zone; its sole occurrence can thus not specify the age of the beds with G. crippsi at Lüneburg (but see discussion on faunal migrations from the Western Interior Seaway below). However, the event-like occurrence of common large G. crippsi is a unique stratigraphic feature of the upper S. schlueteri Subzone (Gale 1995; Wilmsen 2012). Based on the biofacies and the biostratigraphic data, the excavated layer at Lüneburg definitely corresponds to this acme occurrence. In a sequence stratigraphic context, the beds with common G. crippsi are always capped by the first intra-Cenomanian sequence boundary (SB Ce 1; Robaszynski et al. 1998; Wilmsen 2003) but this stratigraphic superposition cannot be deduced from Lüneburg section.

Palaeontological events (cf. Brett and Baird 1997), termed bioevents by Ernst et al. (1983) in their seminal paper on early Late Cretaceous stratigraphic events in northern Germany, are a specific character of Cretaceous epicontinental strata in Europe, forming important marker beds that have widely been used for intra- and interbasinal correlation (e.g. Kauffman and Hart 1995). They comprise widespread single beds or thin bundles of strata that are either characterized by “exotic” fossils or unusual concentrations of rather common faunal elements (e.g. Ernst et al. 1983; Dahmer and Ernst 1986; Küchler 1998; Lehmann 1999; Wiese et al. 2004, 2009; Wilmsen and Voigt 2006; Wilmsen et al. 2007; Wilmsen 2008; Amédro et al. 2012; Nagm 2019). Some of the Late Cretaceous bioevents identified in the pioneering study of Ernst et al. (1983) have already been related to sea-level fluctuations (“Eustato-Events”), but a more general relationship between Cretaceous sequence stratigraphy and bioevent formation has been suggested somewhat later (Ernst et al. 1996; Wilmsen 2003, 2012; see also Brett 1995 for a more general approach on stratigraphic palaeontology and sequence stratigraphy).

Late highstand bioevents (LHB) commonly comprise hard-part accumulations formed as a result of winnowing of fines and concentration of biotic remains by storm currents and/or ground-touching waves (Wilmsen 2012). Their formation is related to shallowing (normal regression) and filling of accommodation during the late highstands of 3rd-order depositional sequences and 4th-order high-frequency sequences. LHBs in 3rd-order sequences correspond to toplap shell beds sensu Kidwell (1991) and the “top-highstand concentrations” of Fürsich and Pandey (2003). In high-frequency sequences, they find their equivalents in the top-of-parasequence shell beds of Banerjee and Kidwell (1991) and the toplap shell bed of Naish and Kamp (1997).

There are only a few well-documented examples of Cretaceous LHBs so far as most of the widespread and correlatable Cretaceous bioevents formed during initial rise (early transgressive bioevents, ETB) and sea-level maxima (maximum flooding bioevents, MFB; e.g. Ernst et al. 1996; Wilmsen 2003, 2008, 2012; Wilmsen et al. 2007). In northern Germany, Late Cretaceous LHBs are often associated with relatively carbonate-rich strata and coarse-grained bioclastic fabrics and commonly consist of pauci- or even monospecific skeletal concentrations with a considerable degree of fragmentation and convex-up orientation of shells (Fig. 4c, e). Single-event (i.e. tempestites) and multiple-event concentrations have been differentiated (Wilmsen 2012), but even for the latter subtype, the absence of significant taphonomic alteration (boring, encrusting) argues against substantial time-averaging (Brett 1995 also mentions relatively high sedimentation rates during this phase of a sequence, augmenting the dilution effect). Overall, the significance of LHBs for interbasinal correlation is rather low because their formation may be predominantly controlled by local to regional processes (such as storms or localized winnowing across a limited submarine topography); furthermore, their preservation potential is low because of common erosion at the sequence boundary capping the highstand deposits (Wilmsen 2012).

The crippsi Event from Lüneburg deviates in some aspects from the abovementioned propositions. The large size and thin shell of the numerous complete valves of G. crippsi suggest little transport and overall low energy albeit some fragmentation and the predominant convex-up orientation of valves suggest episodically elevated water energy (e.g. Fürsich and Oschmann 1993; Fürsich 1995). The microfacies analysis reveals a fine-grained mud- to wackestone fabric dominated by planktonic components (c-dinocysts, planktic foraminifers), suggesting a predominantly low-energy, open shelf environment dominated by vertical accretion of fine-grained particles (planktonic rain; cf. Turner 2002). Based on the sedimentary facies and bioturbation pattern, the sea-bottom was evidently a softground on which epibenthic organisms such as inoceramids would benefit from a large resting surface and low weight. From the perspective of functional morphology, the flat, disc-like form and thin shell of G. crippsi are thus most likely an adaption to a recumbent lifestyle (see also Kauffman et al. 2007 for Platyceramus). Some groups of (inferred chemosymbiontic) inoceramid bivalves are well-known to occur in oxygen-deficient environments where they may predominate the benthic assemblages (Hilbrecht and Dahmer 1991; MacLeod and Hoppe 1992; Kauffman et al. 2007). Weak support for this hypothesis comes from the presence of framboidal pyrites observed in thin section (Fig. 4b) that may reflect oxygen deficiency in the upper sediment pile during early diagenesis (e.g. Kauffman et al. 2007; Mozer 2010). However, the broad size distribution and occurrence of large pyrite specimens (> 10 μm) indicates only modest oxygen depletion, i.e. upper dysaerobic conditions (e.g. Wignall and Newton 1998), and the presence of a moderately diverse and abundant assemblage of other benthic taxa than the inoceramids (ca. 15–20 species and ca. 150 specimens, see results on biofacies above) also argue against significant oxygen depletion [oxygen-restricted biofacies (ORB) 6 of the upper dysaerobic zone sensu Wignall (1994)]. On the other hand, deep infaunal biota are completely missing from the benthic assemblage of the crippsi Event at Lüneburg and also shallow-infaunal taxa are rare (i.e. Palaega carteri or Cardiaster granulosus). However, such a predominance of epibenthic taxa in macrobenthic offshore assemblages from Upper Cretaceous chalks has also been demonstrated by Engelke et al. (2016), without any palaeoecological (Engelke et al. 2017) or geochemical (Engelke et al. 2018) evidence for oxygen restriction.

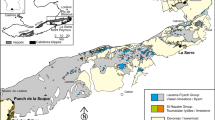

When tracked on an interbasinal scale, conspicuous stratigraphic patterns can be identified from the strata containing the crippsi Event (Fig. 9). In all sections, the event interval consists of five asymmetric bedding couplets grading from more marly/argillaceous sediments below to more calcareous sediments at the top (labeled a–e in Fig. 9). The thickness of the individual basic cycles varies from 0.2 to 1.3 m. Together, they form a bundle of couplets that gets more calcareous up-section and is terminated by a conspicuous unconformity surface interpreted as oldest intra-Cenomanian sequence boundary (SB Ce 1) capping depositional sequence DS Ce 1 (Gale 1995; Robaszynski et al. 1998; Wilmsen 2003; Janetschke et al. 2015). This depositional sequence started at a terminal Albian sequence boundary (SB Al 11) and, on the wide NW European epicontinental shelf, subsequent lowstand deposits straddling the Albian–Cenomanian boundary are only developed in deep intra-shelf basins due to the widespread lack of accommodation in up-dip settings (e.g. Bornemann et al. 2017). The transgressive systems tract started with the ultimus/Aucellina Event in the earliest Cenomanian and costal onlap continued into the late highstand of DS Ce 1 as shown by the unconformable superposition of the crippsi Event bundle onto upper Albian claystones in Cap-Blanc-Nez (Robaszynski et al. 1998; Amédro et al. 2002; Fig. 9). The main occurrence of the crippsi Event relates to the lower four couplets a–d of the bundle and may vary between the sections (Fig. 9). The uppermost couplet (e) of the crippsi Event bundle is commonly rather poor in inoceramids. Its terminal surface (SB Ce 1) is a burrowed unconformity that has been reworked by the subsequent transgression; a lag of small rounded lithoclasts derived from the substrate suggests that the surface has been lithified before the deposition of the early transgressive sandy to argillaceous, glauconite-bearing strata above took place.

Interbasinal correlation of the early Cenomanian crippsi Event. a Cap-Blanc-Nez modified after Amédro et al. (2012). b Folkestone modified after Gale and Friedrich (1989). c Halle-Ascheloh modified after Richardt (2010) and Wilmsen (2012). d Hannover-Anderten (Wilmsen, unpubl.). e Konrad-101 modified after Niebuhr et al. (2001). See Fig. 1 for key to symbols and for location of the sections (the Lüneburg section is situated approximately 80 km to the north-northeast of Hannover)

Striking is the in part very dense packing of the inoceramid shells within the crippsi Event which can be seen in many places [e.g. Lüneburg as demonstrated herein and already mentioned by von Strombeck 1863, p. 108: “…, wo in einzelnen Bänken die Schalen dicht angehäuft sind.”; but see also Richardt (2010) for the Halle-Ascheloh, and Amédro et al. (2012) for the Cap-Blanc-Nez sections; Fig. 9]. The distribution of the shells across three to four marl-limestone bedding couplets rules out single or even several storm events for the concentration of shell but rather suggests a moderately prolonged phase of increased shell production and/or preservation, favoured by the late highstand conditions (e.g. relatively rapid burial). Temporal constraints can be derived from the couplet stratigraphy developed for the Cenomanian of the Anglo-Paris Basin (and beyond) by Gale (1990, 1995) and Gale et al. (1999) who suggested an orbital control for the cyclic bedding patterns. The authors convincingly argued that a marllimestone couplet can be assigned to the precession cycle of the Milankovitch frequency band, comprising ca. 21 kyr in the Cenomanian. The bedding couplets are commonly bundled into sets of five, reflecting the precession–(short) eccentricity syndrome (Gale 1990; Wilmsen 2003). The bundle containing the crippsi Event comprises such a short-eccentricity cycle (ca. 105 kyr), the event duration, thus amounting to 60–85 kyr. We thus propose a geologically short (< 100 kyr) inoceramid bloom in the early part of the early Cenomanian (mid-Mantelliceras mantelli Zone) that resulted in relatively dense populations on the seafloor across large shelf areas. This acme distribution of G. crippsi can thus also be interpreted as a proliferation bioevent (epibole) sensu Brett and Baird (1997), triggered by an interregional population bloom. Concentration by storm amalgamation (but also physical destruction) of the shells increased towards the basin margins where sand- and glaucony-bearing, marly shell-detrital facies prevailed (e.g. Konrad-101 borehole; Niebuhr et al. 2001). However, as shown by the limited taphonomic alteration of the crippsi Event assemblage in Lüneburg, the seafloor must have partly really been paved by inoceramids, also in the deeper part of the basin where physical concentration of shells played a subordinate role. These observations indicate a formation as a primary biogenic concentration with relatively high shell density grading into storm wave-reworked concentrations towards the proximal areas (cf. Fürsich and Oschmann 1993).

Of particular importance is the occurrence of Gnesioceramus mowriensis within the crippsi Event at Lüneburg, known so far only from lower Cenomanian strata of the US Western Interior Seaway (Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016; see Fig. 10a). The presence of the species in northwestern Europe suggests faunal exchange between North America and the Old World during the mid-early Cenomanian. North American immigration is also supported by the occurrence of the ammonite Metengonoceras teigenense Cobban and Kennedy, 1989, endemic to the Western Interior Seaway, in exactly the same stratigraphic horizon (i.e. the crippsi Event level) in Basse-Normandie (France; see Amédro et al. 2002; Fig. 10a, b). G. crippsi was not specifically mentioned from the Boëcé section but the characteristic ammonite assemblage (cf. Gale and Friedrich 1989), the terminal S. schlueteri subzonal age, and the superposition by sequence boundary SB Ce 1 provide firm support for the correlation of the French site with the crippsi Event (Fig. 10b). Dispersal of marine Cretaceous faunas often occurred during the transgressive and maximum flooding intervals of sequences (e.g. the belemnite Events in the Cenomanian; Gale and Christensen 1996; Mitchell 2005; Wilmsen et al. 2007, 2010; Wilmsen 2012), but in this case, a late highstand position of both G. mowriensis and M. teigenense can be ascertained as the crippsi Event bundle is capped by the interregional sequence boundary Cenomanian 1 (Robaszynski et al. 1998; Wilmsen 2003; Janetschke et al. 2015; see discussion above). However, common immigration events during highstands have been proposed by Brett (1998) based on altered water mass properties and open migration pathways following the transgressive re-organisation of the shelf seas. We speculate that the stability of the water masses and oceanic currents during the highstand acted as a driver of faunal dispersal. Amédro et al. (2002) assume a migration of M. teigenense from the Mowry Sea of the Western Interior Seaway via a southern route across the Gulf of Mexico and along the northwestern margin of the Central Atlantic Ocean to Europe, also considering postmortem drift of empty shells. However, the oxycone shell form of M. teigenense is not appropriate for prolonged floating (Yacobucci 2018). Furthermore, the contemporaneous dispersal of benthic inoceramids (G. mowriensis) suggests the existence of appropriate (NE-directed) surface currents for the distribution of their planktotrophic larvae (cf. Kauffman 1975; Knight and Morris 1996 and Tanoue 2003 demonstrated the existence of planktotrophic larvae in inoceramids). Scheltema (1977) showed that the planktic stages of different mollusk groups last up to one year and that planktic larvae can easily be spread across oceans in a few months based on temporal constraints of modern trans-ocean surface currents. Consequently, a dispersal of planktotrophic inoceramid larvae from the Western Interior to Europe by means of a NE-directed surface current seems a plausible explanation. This current may have distributed warm surface waters from the Gulf of Mexico towards Europe (Fig. 10a) in the form of a proto-Gulf stream (see also Amédro et al. 2002, fig. 4). Considering the warm-water preference of many engonoceratid ammonites, being latitudinally restricted to warm-temperate to tropical zones of the Cretaceous oceans (e.g. Kennedy and Cobban 1976; Kennedy et al. 2009; see also Ifrim et al. 2015 and Lehmann et al. 2015), a northerly dispersal route of the Western Interior faunas via the Arctic Ocean towards Europe (Fig. 10a) is much less likely. The presence of M. teigenense in western France (Amédro et al. 2002) thus supports the existence of a warm proto-Gulf stream in early Cenomanian times. Further support for this interpretation comes from the development of relatively large and diverse coral reefs in Cantabria, northern Spain, in relatively high palaeolatitudes during the early Cenomanian (Wilmsen 1996, 2000), and the prevalence of contemporaneous warm-water biofacies in the Aquitaine Basin of western France (e.g. Masse and Philip 1981; Francis 1984), forming potential fingerprints of this warm-water current on its way to the northeast (Fig. 10a).

Palaeogeographic and stratigraphic framework of faunal migrations associated with the crippsi Event. a Cenomanian palaeogeography (after Scotese 2014, sea level + 80 m, Mollweide projection) showing the occurrences of G. mowriensis and M. teigenense as well as the diverse early Cenomanian coral reefs in northern Cantabria (AB, Aquitaine Basin; APB, Anglo-Paris Basin; MEI, Mid-European Island; NSB, North Sea Basin; NGB, North German basins; WIS, Western Interior Seaway; see text for discussion). b Geochronological framework of the crippsi Event related to the NW European standard biozonation (1, modified and supplemented after Wright and Kennedy 2017) and correlated to the North American ammonite record (ammonite biozonation and ages from Ogg and Hinnov 2012, faunal ranges after Cobban and Kennedy 1989; Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016) as well as the Boëcé section in Basse-Normandie (where M. teigenense was recorded) by Amédro et al. (2002)

The early Cenomanian species Gnesioceramus mowriensis appeared in the Western Interior Seaway during the Neogastroplites cornutus ammonite Zone (Walaszczyk and Cobban 2016; zone base at ca. 99.20 Ma according to Ogg and Hinnov 2012) and ranges through the N. muelleri Zone (base at 98.75 Ma, top at 98.20 Ma) up to the N. americanus Zone (top at 97.80 Ma); the maximum duration of the species is thus ca. 1.4 myr (Fig. 10b). Its brief appearance in Europe, documented herein, comprises a short interval from the middle part of its North American range as can be demonstrated by the occurrence of M. teigenense in the correlative level of the crippsi Event in the Boëcé section, Basse-Normandie, just below sequence boundary SB Ce 1 (= hardground Coulimer 1; Amédro et al. 2002): the ammonite species is known only from the N. muelleri Zone of Montana (Cobban and Kennedy 1989). When the North American ammonite zones are plotted against the European standard zonation (cf. Wright and Kennedy 2017), it can be shown that the uppermost Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone of the Mantelliceras mantelli Zone in Europe must correlate to the lowermost N. muelleri Zone in North America (Fig. 10b). Accepting this tie point, the absolute age of the crippsi Event may be defined as ca. 98.6–98.7 Ma.

Conclusions

Palaeontological events (or bioevents) are a specific feature of Cretaceous epicontinental strata in Europe, forming important marker beds for intra- and interbasinal correlation. The lower Cenomanian crippsi Event comprises a thin interval of strata (1–3 m) characterised by the mass occurrence of valves of the early Cenomanian inoceramid bivalve Gnesioceramus crippsi (Mantell, 1822), identified in the uppermost part of the Sharpeiceras schlueteri Subzone of the lower lower Cenomanian Mantelliceras mantelli ammonite Zone, below an interregional sedimentary unconformity (sequence boundary SB Ce 1). At Lüneburg, the event beds are characterised by a dense packing of mostly complete, disc-like valves of G. crippsi with limited taphonomic alteration. Bio- and microfacies data suggest an event formation in a deeper shelf setting on a soft substrate below the storm-wave base as a primary biogenic concentration with the inoceramid bivalves living as inferred recumbent forms in relatively dense populations. When tracked on an interbasinal scale across the North German shelf into the Anglo-Paris Basin, the distribution of the crippsi Event across three to four marl-limestone bedding couplets of a couplet bundle, reflecting orbital forcing by the precession/short-eccentricity syndrome, suggests a moderately prolonged phase (< 105 kyr) of increased shell production. Rapid deposition during the late highstand phase of depositional sequence Cenomanian 1 aided in preserving the shell-rich event strata. The crippsi Event can thus be interpreted as a proliferation bioevent (epibole) sensu Brett and Baird (1997), triggered by an interregional population bloom. Towards the basin margin, it grades into storm wave-reworked shell concentrations.

Of particular importance is the occurrence of Gnesioceramus mowriensis Walaszczyk and Cobban, 2016 within the crippsi Event at Lüneburg, formerly only known from lower Cenomanian strata of the US Western Interior Seaway. Together with the ammonite Metengonoceras teigenense Cobban and Kennedy, 1989, likewise an endemic North American mid-early Cenomanian faunal element known as a single find from the level of the crippsi Event in northern France, these taxa indicate faunal exchange between North America and Europe during the early Cenomanian. Albeit postmortem drift of an empty ammonite shell cannot completely be excluded for M. teigenense, the contemporaneous dispersal of benthic inoceramids (G. mowriensis) rather suggests the existence of a perpetual NE-directed surface current for the distribution of their planktotrophic larvae. This inferred proto-Gulf stream transported warm surface waters from the Gulf of Mexico towards Europe, supported by the existence of warm-water biofacies in Western Europe during the early Cenomanian. Furthermore, the disjunct occurrence of the short-lived species M. teigenense in France allows for the calibration of the uppermost schlueteri Subzone of the mantelli Zone in Europe to the lowermost Neogastroplites muelleri Zone in North America, assigning an absolute age of ca. 98.6–98.7 Ma to the crippsi Event.

References

Amédro, F., Cobban, W. A., Breton, G., & Rogron, P. (2002). Metengonoceras teigenense Cobban et Kennedy, 1989: une ammonite exotique d’origine Nord-américaine dans le Cénomanien inférieur de Basse-Normadie (France). Bulletin trimestriel de la Société géologique de Normandie et des amis du Muséum du Havre, 87, 5–28.

Amédro, F., Matrion, B., Touch, R., & Verrier, J.-M. (2012). Extension d’un niveau repère riche en Inoceramus crippsi (bivalve) dans le Cénomanien basal du Bassin Anglo-Parisien. Annales de la Société Géologique du Nord, 19 (2ième série), 9–23.

Banerjee, I., & Kidwell, S. M. (1991). Significance of molluscan shell beds in sequence stratigraphy: an example from the Lower Cretaceous Mannville Group of Canada. Sedimentology, 38, 913–934.

Beurlen, K. (1944). Beiträge zur Stammesgeschichte der Muscheln. Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sitzungsberichte, 1–2, 133–145.

Boehm, J. (1909). Über Inoceramus cripsi auctorum. In H. Schroeder, & J. Boehm, (Eds.), Geologie und Paläontologie der Subhercynen Kreidemulde. Abhandlungen der königlich-preussischen Geologischen Landesanstalt, Neue Folge, 56, 39–58, pls 9–14.

Bornemann, A., Erbacher, J., Heldt, M., Kollaske, T., Wilmsen, M., Lübke, N., Huck, S., Vollmar, N. M., & Wonik, T. (2017). The Albian–Cenomanian transition and Oceanic Anoxic Event 1d–an example from the Boreal Realm. Sedimentology, 64, 44–65.

Bower, C. R., & Farmery, J. R. (1910). The zones of the Lower Chalk of Lincolnshire. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 21, 333–359.

Brett, C. E. (1995). Sequence stratigraphy, biostratigraphy, and taphonomy in shallow marine environments. Palaios, 10, 597–616.

Brett, C. E. (1998). Sequence stratigraphy, paleoecology, and evolution: biotic clues and responses to sea level fluctuations. Palaios, 13, 241–262.

Brett, C. E., & Baird, G. C. (1997). Epiboles, outages, and ecological evolutionary bioevents: taphonomic, ecological, and biogeographic factors. In C. E. Brett & G. C. Baird (Eds.), Paleontological events (pp. 249–284). New York: Columbia University Press.

Carter, J. G., Altaba, C. R., Anderson, L. C., Araujo, R., Biakov, A. S., Bogan, A. E., Campbell, D. C., Campbell, M., Jin-hua, C., Cope, J. C. W., Delvene, G., Dijkstra, H. H., Zong-jie, F., Gardner, R. N., Gavrilova, V. A., Goncharova, I., Harries, P. J., Hartman, J. H., Hautmann, M., Hoeh, W. R., Hylleberg, J., Bao-yu, J., Johnston, P., Kirkendale, L., Kleemann, K., Koppka, J., Kříž, J., Machado, D., Malchus, N., Márquez-Aliaga, A., Masse, J.-P., McRoberts, C. A., Middelfart, P. U., Mitchell, S., Nevesskaja, L. A., Özer, S., Pojeta Jr., J., Polubotko, I. V., Pons, J. M., Popov, S., Sánchez, T., Sartori, A. F., Scott, R. W., Sey, I. I., Signorelli, J. H., Silantiev, V. V., Skelton, P. W., Steuber, T., Waterhouse, J. B., Wingard, G. L., & Yancey, T. (2011). A synoptical classification of the Bivalvia (Mollusca). Paleontological Contributions, 4, 1–47.

Cieśliński, S. (1987). Inoceramy Albu i Cenomanu Polski I ich znaczenie stratygraficzne. Biuletyn Instytutu Geologicznego, 354, 11–62.

Cobban, W. A., & Kennedy, W. J. (1989). The ammonite Metengonoceras Hyatt, 1903, from the Mowry Shale (Cretaceous) of Montana and Wyoming. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin, 1787-L, L1–L11.

Dahmer, D.-D., & Ernst, G. (1986). Upper Cretaceous event-stratigraphy in Europe. In O. Walliser (Ed.) Global bio-events. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences, 8, 353–362.

Engelke, J., Esser, K. J. K., Linnert, C., Mutterlose, J., & Wilmsen, M. (2016). The benthic macrofauna from the lower Maastrichtian chalk of Kronsmoor (northern Germany, Saturn quarry): taxonomic outline and palaeoecologic implications. Acta Geologica Polonica, 66, 671–694.

Engelke, J., Linnert, C., Mutterlose, J., & Wilmsen, M. (2017). Early Maastrichtian benthos of the chalk of Kronsmoor (northern Germany): implications for Late Cretaceous environmental change. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 97(4), 703–722.

Engelke, J., Linnert, C., Niebuhr, B., Schnetger, B., Brumsack, H.-J., Mutterlose, J., & Wilmsen, M. (2018). Tracking Late Cretaceous environmental change: geochemical environment of the upper Campanian to lower Maastrichtian chalks at Kronsmoor, northern Germany. Cretaceous Research, 84, 323–339.

Ernst, G., & Rehfeld, U. (1997). Transgressive development in the Early Cenomanian of the Salzgitter area (northern Germany) recorded by sea level controlled eco- and litho-events. Freiberger Forschungshefte, C, 468, 79–107.

Ernst, G., & Wood, C. J. (1995). Die tiefere Oberkreide des subherzynen Niedersachsens. Terra Nostra, 5(95), 41–84.

Ernst, G., Schmid, F., & Klischies, G. (1979). Multistratigraphische Untersuchungen in der Oberkreide des Raumes Braunschweig-Hannover. In J. Wiedmann (Ed.), Aspekte der Kreide Europas, IUGS Series, A (Vol. 6, pp. 11–46).

Ernst, G., Schmid, F., & Seibertz, E. (1983). Event-Stratigraphie im Cenoman und Turon von NW-Deutschland. Zitteliana, 10, 531–554.

Ernst, G., Niebuhr, B., Wiese, F., & Wilmsen, M. (1996). Facies development, basin dynamics, event correlation and sedimentary cycles in the Upper Cretaceous of selected areas of Germany and Spain. In J. Reitner, F. Neuweiler, & F. Gunkel (Eds.), Global and regional controls on biogenic sedimentation. II. Cretaceous sedimentation. Research Reports. Göttinger Arbeiten zur Geologie und Paläontologie, Sb3 (pp. 87–100).

Ernst, W. (1921). Über den oberen Gault von Lüneburg. Zeitschrift der deutschen geologischen Gesellschaft, 73, 291–321, pls 11, 12.

Francis, I. H. (1984). Correlation between the North Temperate and Tethyan realms in the Cenomanian of western France and the significance of hardground horizons. Cretaceous Research, 5, 259–269.

Fürsich, F. T. (1995). Shell concentrations. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 88, 643–655.

Fürsich, F. T., & Oschmann, W. (1993). Shell beds as a tool in basin analysis: the Jurassic of Kachchh, western India. Journal of the Geological Society London, 150, 169–185.

Fürsich, F. T., & Pandey, D. K. (2003). Sequence stratigraphic significance of sedimentary cycles and shell concentrations in the Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous of Kachchh, western India. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 193, 285–309.

Gale, A. S. (1990). A Milankovitch scale for Cenomanian time. Terra Nova, 1, 420–425.

Gale, A.S. (1995). Cyclostratigraphy and correlation of the Cenomanian stage in Western Europe. In M.R House & A.S. Gale (Eds.) Orbital forcing timescales and cyclostratigraphy. Geological Society London, Special Publications, 85, 177–197.

Gale, A. S., & Friedrich, S. (1989). Occurrence of the ammonite Sharpeiceras in the Lower Cenomanian Chalk Marl of Folkstone. Proceedings of the Geologist’s Association, 100, 80–82.

Gale, A. S., & Christensen, W. K. (1996). Occurrence of the belemnite Actinocamax plenus in the Cenomanian of SE France and its significance. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, 43, 68–77.

Gale, A. S., Young, J. R., Shackleton, N. J., Crowhurst, S. J., & Wray, D. S. (1999). Orbital tuning of Cenomanian marly chalk successions: towards a Milankovitch time-scale for the Late Cretaceous. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 357, 1815–1829.

Giebel, C.G. (1852). Allgemeine Palaeontologie. Entwurf einer systematischen Darstellung der Fauna und Flora der Vorwelt. I. Abtheilung: Palaeozoologie. viii + 328 pp. Leipzig: Ambrosius Abel.

Heinz, R. (1926). Neuere Beobachtungen über die Oberkreide Lüneburgs. Jahreshefte des naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins für das Fürstentum Lüneburg, 23, 2–10, 1 pl.

Heinz, R. (1932). Aus der neuen Systematik der Inoceramen. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der oberkretazischen Inoceramen XIV. Mitteilungen aus dem Mineralogisch-Geologischen Staatsinstitut in Hamburg, 13, 1–26.

Hilbrecht, H., & Dahmer, D.-D. (1991). Inoceramen aus den Schwarzschiefern des basalen Unterturon (Oberkreide) von Helgoland und Misburg. Geologisches Jahrbuch, A, 120, 245–269.

Hiss, M. (1995). Kreide. In Geologischer Dienst Nordrhein-Westfalen (Ed.), Geologie im Münsterland (pp. 41–63). Krefeld: Geologischer Dienst Nordrhein-Westfalen (GD NRW).

Holland, S. M. (2000). The quality of the fossil record: a sequence stratigraphic perspective. Paleobiology, 26, 148–168.

Holland, S. M. (2001). Sequence stratigraphy and fossils. In D. E. G. Briggs & P. R. Crowther (Eds.), Palaeobiology II (pp. 548–553). Oxford: Blackwell.

Ifrim, C., Lehmann, J., & Ward, P. D. (2015). Paleobiogeography of Late Cretaceous ammonoids. In C. Klug, D. Korn, K. De Baets, I. Kruta, & R. H. Mapes (Eds.), Ammonoid paleobiology: from macroevolution to paleogeography. Topics in Geobiology (Vol. 44, pp. 259–274).

Janetschke, N., Niebuhr, B., & Wilmsen, M. (2015). Inter-regional sequence stratigraphical synthesis of the Plänerkalk, Elbtal and Danubian Cretaceous groups (Germany): Cenomanian–Turonian correlations around the mid-European Island. Cretaceous Research, 56, 530–549.

Jeans, C. V. (1980). Early submarine lithification in the Red Chalk and Lower Chalk of eastern England; a bacterial control model and its implications. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society, 43, 81–157.

Kaplan, U., & Best, M. (1985). Zur Stratigraphie der tiefen Oberkreide im Teutoburger Wald (NW-Deutschland). Teil 1: Cenoman. Berichte des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins Bielefeld und Umgegend, 27, 81–103.

Kaplan, U., Keller, S., & Wiedmann, J. (1984). Ammoniten- und Inoceramen-Gliederung des nordeutschen Cenoman. Schriftenreihe der Erdwissenschaftlichen Kommission, 7, 307–347.

Kaplan, U., Püttmann, T., & Scheer, U. (2019). Biostratigraphie kreidezeitlicher Transgressionssedimente im “Geologischen Garten” von Bochum-Wiemelshausen (Münsterländer Becken, zentrales Ruhrgebiet). Geologie und Paläontologie in Westfalen, 91, 25–36.

Kauffman, E. G. (1975). Dispersal and biostratigraphical potential of Cretaceous benthonic Bivalvia in the Western Interior. In W. G. E. Caldwell (Ed.), The Cretaceous system in the Western Interior of North America. Special Paper of the Geological Association of Canada (Vol. 13, pp. 163–194).

Kauffman, E. G., & Hart, M. B. (1995). Cretaceous bio-events. In H. Walliser (Ed.), Global events and event stratigraphy in the Phanerozoic (pp. 285–312). Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Kauffman, E. G., Hattin, D. E., & Powell, J. D. (1977). Stratigraphic, paleontologic, and paleoenvironmental analysis of the Upper Cretaceous rocks of Cimarron County, northwestern Oklahoma. Geological Society of America Memoir, 149, 1–150 pls. 1–12.

Kauffman, E. G., Harries, P. J., Meyer, C., Villamil, T., Arango, C., & Jaecks, G. (2007). Paleoecology of giant Inoceramidae (Platyceramus) on a Santonian (Cretaceous) seafloor in Colorado. Journal of Paleontology, 81, 64–81.

Keller, S. (1982). Die Oberkreide der Sack-Mulde bei Alfeld (Cenoman-Unter-Coniac)-Lithologie, Biostratigraphie und Inoceramen. Geologisches Jahrbuch, A, 64, 1–171.

Kennedy, W. J., & Cobban, W. A. (1976). Aspects of ammonite biology, biogeography, and biostratigraphy. Special Papers in Palaeontology, 17, 1–94.

Kennedy, W. J., Reyment, R. A., Macleod, N., & Krieger, J. (2009). Species discrimination in the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) ammonite genus Knemiceras von Buch, 1848. Palaeontographica, 209, 1–63.

Kidwell, S. M. (1991). Condensed deposits in siliciclastic sequences: expected and observed features. In G. Einsele, W. Ricken, & A. Seilacher (Eds.), Cycles and events in stratigraphy (pp. 682–695). Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Kilpady, S., & Kulkarni, P. H. (1956). A giant Inoceramus crippsi from the Cretaceous of the Trichinopoly area. Journal of the University Nagpur Geological Society, 1(3), 1–3.

Knight, R. I., & Morris, N. J. (1996). Inoceramid larval planktotrophy: evidence from the Gault Formation (Middle and basal Upper Albian), Folkestone, Kent. Palaeontology, 29, 1027–1036.

Küchler, T. (1998). Upper Cretaceous of the Barranca (Navarra, northern Spain); integrated litho-, bio- and event stratigraphy. Part I: Cenomanian through Santonian. Acta Geologica Polonica, 48, 157–263.

Lehmann, J. (1999). Integrated stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the Cenomanian-Lower Turonian (Upper Cretaceous) of northern Westphalia, North Germany. Facies, 40, 25–70.

Lehmann, J., Ifrim, C., Bulot, L., & Frau, C. (2015). Paleobiogeography of Early Cretaceous ammonoids. In C. Klug, D. Korn, K. De Baets, I. Kruta, & R. H. Mapes (Eds.), Ammonoid Paleobiology: From macroevolution to paleogeography. Topics in Geobiology (Vol. 44, pp. 229–257).

Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Volume 1. 824 pp. Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii.

MacLeod, K. G., & Hoppe, K. A. (1992). Evidence that inoceramid bivalves were benthic and harboured chemosynthetic symbionts. Geology, 20, 117–120.

Mantell, G.A. (1822). The fossils of the South Downs, or illustrations of the Geology of Sussex. xiv + 328 pp, 43 pls. London: Lupton Relfe.

Masse, J.-P., & Philip, J. (1981). Cretaceous coral-rudist buildups of France. In D.F. Toomey (Ed.) European fossil reef models. Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (SEPM) Special Publication, 30, 399–426.

Mitchell, S. F. (2005). Eight belemnite biohorizons in the Cenomanian of Northwest Europe and their importance. Geological Journal, 40, 363–382.

Mozer, A. (2010). Authigenic pyrite framboids in sedimentary facies of the Mount Wawel Formation (Eocene), King George Island, West Antarctica. Polish Polar Research, 31, 255–272.

Nagm, E. (2019). The late Cenomanian maximum flooding Neolobites bioevent: a case study from the Cretaceous of northeast Egypt. Marine and Petroleum Geology, 102, 740–750.

Naish, T., & Kamp, P. J. J. (1997). Sequence stratigraphy of 6th order (41 k.y.) Plio–Pleistocene cyclothems, Wanganui Basin, New Zealand: a case for the regressive systems tract. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 109, 978–999.

Newell, N. D. (1965). Classification of the Bivalvia. American Museum Novitates, 2206, 1–25.

Niebuhr, B., Wiese, F., & Wilmsen, M. (2001). The cored Konrad 101 borehole (Cenomanian–Lower Coniacian, Lower Saxony): calibration of surface and subsurface log data for the lower Upper Cretaceous of northern Germany. Cretaceous Research, 22, 643–674.

Niebuhr, B., Hiss, M., Kaplan, U., Tröger, K.-A., Voigt, S., Voigt, T., Wiese, F., & Wilmsen, M. (2007). Lithostratigraphie der norddeutschen Oberkreide. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, 55, 1–136.

Ogg, J.G., & Hinnov, L.A. (2012). Cretaceous. In F.M. Gradstein, J.G. Ogg, M. Schmitz & G.M. Ogg (Eds.) The geologic time scale 2012, Volume 2 (pp. 793–853). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Pokhialainen, V.P. (1985a). The basis for a supra-species systematics of Cretaceous inoceramid bivalves. 37 pp. Magadan: Akademia Nauk USSR, SVKNIIN-DVNC. [In Russian].

Pokhialainen, V. P. (1985b). Albian and Cenomanian Mollusca of the Mowry Sea and its equivalents in the northern Pacific Ocean. Tikhookeanskja Geologija, 1985(5), 15–22 [In Russian].

Püttmann, T., Mutterlose, J., Kaplan, U., & Scheer, U. (2019). Reworking of Cenomanian ammonites decoded by calcareous nannofossils (southern Münsterland Basin, northwest Germany). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen, 291, 1–17.

Richardt, N. (2010). Das Cenoman von Halle/Westfalen: eine integrierte sedimentologisch-stratigraphische, geochemische und geophysikalische Analyse. Geologie und Paläontologie in Westfalen, 78, 5–60.

Robaszynski, F., Juignet, P., Gale, A.S., Amédro, F., & Hardenbol, J. (1998). Sequence stratigraphy in the Cretaceous of the Anglo-Paris Basin, exemplified by the Cenomanian stage. In T. Jaquin, P. de Graciansky & J. Hardenbol (Eds.) Mesozoic and Cenozoic sequence stratigraphy of European basins. Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Special Publication, 60, 363–385.

Scheltema, R. S. (1977). Dispersal of marine invertebrate organisms: paleobiogeographic and biostratigraphic implications. In E. G. Kauffman & J. E. Hazel (Eds.), Concepts and methods of biostratigraphy (pp. 73–108). Stroudsburg: Dowden, Hutchinson and Ross.

Schmid, F. (1962). Die Kreide am Zeltberg bei Lüneburg. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 36, 3–5.

Schmid, F. (1963). Die Kreide von Lüneburg und die Aufschürfung des Alb-Profiles im Kreidebruch am Zeltberg. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft, 114, 419–422.

Schneider, S., Jäger, M., Kroh, A., Mitterer, A., Niebuhr, B., Vodrážka, R., Wilmsen, M., Wood, C. J., & Zágoršek, K. (2013). Silicified sea life–macrofauna and palaeoecology of the Neuburg Kieselerde Member (Cenomanian to Lower Turonian Wellheim Formation, Bavaria, southern Germany). Acta Geologica Polonica, 63, 555–610.

Scotese, C. R. (2014). Atlas of Late Cretaceous Maps, PALEOMAP Atlas for ArcGIS, volume 2, The Cretaceous, Maps 16–22, Mollweide Projection. 15 pp. Evanston, Illinois: PALEOMAP Project.

Stein, G. (1992). Der Lüneburger Kalkberg im Wandel der Zeiten. Jahrbuch Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein Fürstentum Lüneburg, 39, 247–258.

Stolley, E. (1896). Einige Bemerkungen über die obere Kreide insbesondere von Lüneburg und Lägerdorf. Archiv für Antropologie und Geologie Schleswig-Holsteins, 1(2), 139–176.

von Strombeck, A. (1863). Ueber die Kreide am Zeltberg bei Lüneburg. Zeitschrift der deutschen geologischen Gesellschaft, 15, 97–187 4 pls.

Stümke, M. (1905). Die geognostischen Verhältnisse Lüneburgs. 11pp. Lüneburg: Stern’sche Buchdruckerei.

Tanoue, K. (2003). Larval ecology of Cretaceous inoceramid bivalves from northwestern Hokkaido, Japan. Paleontological Research, 7, 105–110.

Tröger, K.-A. (1967). Zur Paläontologie, Biostratigraphie und faziellen Ausbildung der unteren Oberkreide (Cenoman-Turon). Teil I–Paläontologie und Biostratigraphie der Inoceramen des Cenomans und Turons. Abhandlungen des Staatlichen Museums für Mineralogie und Geologie zu Dresden, 12, 13–207.

Tröger, K.-A. (1989). Problems of Upper Cretaceous inoceramid biostratigraphy and palaeobiogeography in Europe and western Asia. In J. Wiedmann (Ed.), Cretaceous of the Western Tethys. Proceedings 3rd International Cretaceous Symposium, Tübingen 1987 (pp. 911–930). Stuttgart: Schweizerbart.

Tröger, K.-A. (1995). Die subherzyne Oberkreide–Beziehungen zum variscischen Grundgebirge und Stellung innerhalb Europas. Nova Acta Leopoldina, Neue Folge, 71(291), 217–231.

Tröger, K.-A. (2009). Katalog oberkretazischer Inoceramen. Geologica Saxonica, 55, 1–188.

Tröger, K.-A., Niebuhr, B., & Wilmsen, M. (2009). Inoceramen aus dem Cenomanium bis Coniacium der Danubischen Kreide-Gruppe (Bayern, Süd-Deutschland). Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften, 65, 59–110.

Turner, J. T. (2002). Zooplankton fecal pellets, marine snow and sinking phytoplankton blooms. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 27, 57–102.

Walaszczyk, I., & Cobban, W. A. (2016). Inoceramid bivalves and biostratigraphy of the upper Albian and lower Cenomanian of the United States Western Interior Basin. Cretaceous Research, 59, 30–68.

Wiedmann, J., Kaplan, U., Lehmann, J., & Marcinowski, R. (1989). Biostratigraphy of the Cenomanian of NW Germany. In J. Wiedmann (Ed.), Cretaceous of the Western Tethys. Proceedings 3rd International Cretaceous Symposium, Tübingen 1987 (pp. 931–948). Stuttgart: Schweizerbart.

Wiese, F., Wood, C. J., & Kaplan, U. (2004). 20 years of event stratigraphy in NW Germany; advances and open questions. Acta Geologica Polonica, 54, 639–656.

Wiese, F., Košták, M., & Wood, C.J. (2009). The Upper Cretaceous belemnite Preaactinocamax plenus (Blainville, 1827) from Lower Saxony (Upper Cenomanian, northwest Germany) and its distribution pattern in Europe. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 83, 309–321.

Wignall, P.B. (1994). Black shales. 127 pp. Oxford: University Press.

Wignall, P. B., & Newton, R. (1998). Pyrite framboid diameter as a measure of oxygen deficiency in ancient mudrocks. American Journal of Science, 298, 537–552.

Wilmsen, M. (1996). Flecken-Riffe in den Kalken der “Formación de Altamira” (Cenoman, Cobreces/Toñanes-Gebiet, Prov. Kantabrien, Nord-Spanien): Stratigraphische Position, fazielle Rahmenbedingungen und Sequenzstratigraphie. Berliner geowissenschaftlichen Abhandlungen, E, 18, 353–373.

Wilmsen, M. (2000). Evolution and demise of a mid-Cretaceous carbonate shelf: The Altamira Limestones (Cenomanian) of northern Cantabria (Spain). Sedimentary Geology, 133, 195–226.

Wilmsen, M. (2003). Sequence stratigraphy and palaeoceanography of the Cenomanian Stage in northern Germany. Cretaceous Research, 245, 525–568.

Wilmsen, M. (2007). Integrated stratigraphy of the upper Lower–lower Middle Cenomanian of northern Germany and southern England. Acta Geologica Polonica, 57, 263–279.

Wilmsen, M. (2008). An Early Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) maximum flooding bioevent in NW Europe: correlation, sedimentology and biofacies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 258, 317–333.

Wilmsen, M. (2012). Origin and significance of Upper Cretaceous bioevents: Examples from the Cenomanian. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 57, 759–771.

Wilmsen, M., & Niebuhr, B. (2002). Stratigraphic revision of the upper Lower and Middle Cenomanian in the Lower Saxony Basin (northern Germany) with special reference to the Salzgitter area. Cretaceous Research, 23, 445–460.

Wilmsen, M., & Niebuhr, B. (2010). On the age of the Upper Cretaceous transgression between Regensburg and Neuburg an der Donau (Bavaria, southern Germany). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, 256, 267–278.

Wilmsen, M., & Voigt, T. (2006). The Middle-Upper Cenomanian of Zilly (Sachsen-Anhalt, northern Germany) with remarks on the Pycnodonte Event. Acta Geologica Polonica, 56, 17–31.

Wilmsen, M., Niebuhr, B., & Wood, C. J. (2001). Early Cenomanian (Cretaceous) inoceramid bivalves from the Kronsberg Syncline (Hannover area, Lower Saxony, northern Germany): stratigraphic and taxonomic implications. Acta Geologica Polonica, 51, 121–136.

Wilmsen, M., Niebuhr, B., & Hiss, M. (2005). The Cenomanian of northern Germany: facies analysis of a transgressive biosedimentary system. Facies, 51, 242–263.

Wilmsen, M., Niebuhr, B., Wood, C. J., & Zawischa, D. (2007). Fauna and palaeoecology of the Middle Cenomanian Praeactinocamax primus Event at the type locality, Wunstorf quarry, northern Germany. Cretaceous Research, 28, 428–460.

Wilmsen, M., Niebuhr, B., & Chellouche, P. (2010). Occurrence and significance of Cenomanian belemnites in the lower Danubian Cretaceous Group (Bavaria, southern Germany). Acta Geologica Polonica, 60, 231–241.

Wollemann, A. (1902). Die Fauna der Lüneburger Kreide. Abhandlungen der königlich-preussischen Geologischen Landesanstalt, Neue Folge, 37, 1–129 7 pls (atlas).

Woods, H. (1904−1913). A monograph of the Cretaceous Lamellibranchia of England. Part 2. Monographs of the Palaeontographical Society London, 58 (273), 1–56 [1904], 59 (279), 57–96 [1905], 60 (285), 97–132 [1906], 61 (293), 133–180 [1907], 62 (302), 181–216 [1908], 63 (309), 217–260 [1909], 64 (314), 261–284 [1911], 65 (321), 285–340 [1912], 66 (325), 341–473 [1913].

Wright, C. W., & Kennedy, W. J. (2017). The Ammonoidea of the Lower Chalk. Part 7. The Palaeontographical Society Monograph, 648(171), 461–561.

Yacobucci, M. M. (2018). Postmortem transport in fossil and modern shelled cephalopods. PeerJ, 6, e5909 (29 pp.).

Acknowledgements

Stanislav Čech (Prague) and Ireneusz Walaszczyk (Warsaw) provided insightful, constructive reviews that are highly appreciated and considerably improved the quality of the manuscript. IW is also thanked for discussions on inoceramid identification. Manuel Röthel and Ronald Winkler (SNSD, Dresden) assisted in collection work, in fossil and thin-section preparation, and in digital photography. The active support of Gerhard Stein (Lüneburg) during manuscript preparation is gratefully acknowledged. Finally, we want to thank Sinje Weber and Peter Königshof (both Frankfurt) for the professional editorial handling.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilmsen, M., Schumacher, D. & Niebuhr, B. The early Cenomanian crippsi Event at Lüneburg (Germany): palaeontological and stratigraphical significance of a widespread Late Cretaceous bioevent. Palaeobio Palaeoenv 101, 927–946 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-020-00459-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12549-020-00459-8