Abstract

Building on previous work on US multiraciality, we analyze the messaging patterns of Asian-white, Hispanic-white, and black-white multiracial heterosexual users on one of the largest mainstream dating websites in the USA. We consider how multiracials’ online dating behaviors reflect, accommodate or challenge racialized desirability hierarchies among heterosexual daters. The study’s results illustrate that Hispanic-white multiracial men show similar preferences to both their multiracial and monoracial in-groups, while Asian-white and black-white multiracial men most prefer their multiracial counterparts. Hispanic-white multiracial women, on the other hand, privilege whiteness and multiraciality, while Asian-white multiracial women show most preference for their multiracial in-groups. Overall, our findings illustrate that both multiracial men and women’s online dating behaviors illustrate a linked privileging of white multiraciality while they also reinforce a hierarchical ranking of racial desirability anchored by anti-Blackness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although we do not analyze people of three or more races in this paper due to small sample size, we use the terms biracial and multiracial interchangeably given that multiracial is defined as more than one race while biracial is defined as two races.

Since the website categorizes Asian separately from those from India or the Pacific islands, for example, our Asian category does not apply to users who self-identified as Indians or Pacific Islanders (which tends to be combined with Asian in the Census classification). We do not collapse South Asians with other Asian groups because South Asians often have very different experiences from East Asians (Mishra 2013).

Even though our original data set consists of a large number of users, non-White biracial users are sparse and therefore do not have much opportunity to interact with other daters of the same racial background. For example, compared to more than 10,000 Asian-White users, there are only 2723 Asian-Black users, and 3964 Asian-Hispanic straight male and female users. As such, we focus only on White biracial daters.

Alphabetically, the largest top-20 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) are the following: 12,060 Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA; 12,420 Austin- Round Rock, TX; 12,580 Baltimore-Towson, MD; 14,460 Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH; 16,980 Chicago-Naperville-Joliet, IL-IN-WI; 19,100 Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX; 19,820 Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI; 26,420 Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX; 31,100 Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA; 33,100 Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL; 33,460 Minneapolis- St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI; 35,620 New York- Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA; 37,980 Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ- DE-MD; 38,060 Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ; 38,900 Portland-Vancouver-Beaverton, OR-WA; 41,740 San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA; 41,860 San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA; 42,660 Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA; 45,300 Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL; and 47,900 Washington- Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV.

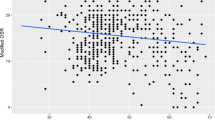

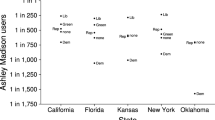

Counting all the initial messages between heterosexual daters in our dataset, less than 25% were sent by women. Overall, straight men send twice as many messages as straight women, and this generally is the case across the various ethnic and racial groups presented. For this reason our analyses focus on the likelihood of a response when assessing women’s messaging behaviors, while for men we focus on their sending behaviors rather than their response behaviors.

Attractiveness data does not include information pertaining to the race of the rater, and, given the majority of users are White, leans toward a predominately White gaze.

GEE logit estimates the same model as standard logistic regression; however, it differs in that it allows for dependence within clusters, optimizing the statistical power of the correlated data by estimating clustered correlations. The advantage to the GEE approach over, for example hierarchical or mixed effects models, is that it makes little demand of within-cluster variance and is more suitable to our data, where a significant number of our observations are singletons and where user participation follows a power-law distribution. The exclusion of singletons would create serious selection bias, making a random intercept approach unsuitable for our analysis. In contrast to other, more network-oriented approaches, GEE requires less computing power and thus handles a much larger population. The drawback is that we must assume a correlation within each sender/responder but not within the other side. However, considering that each individual will have different evaluations of the unmeasured factors of the same individual and there is little network transitivity in the relation of interest (two alters of the same ego do not attract each other in our case), the GEE procedure is the best-suited approach.

Although large confidence intervals due to small N in unshown models for Asian-White, Black-White and Hispanic-White multiracial women’s sending leave the precise sorting mechanism unclear, Asian-White, Black-White and Hispanic-White multiracial women’s sending models appear to indicate they are most likely to send to their same-group multiracial co-ethnics and White men and least likely to send to monoracial Black men. Multiracial men’s unshown response patterns also indicate that they are least responsive to Blacks and most responsive to their Multiracial co-ethnics. The notable difference, however, is that Hispanic-White men have an almost equal probability of responding to Hispanic-White and White woman. Overall, the unshown models align with the analyses of multiracial men’s sending and multiracial women’s response patterns we have presented throughout the paper. That is, anti-Blackness and a persistent privileging of multiraciality characterizes multiracials’ dating behaviors.

References

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bany, J. A., Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2014). Gendered black exclusion: The persistence of racial stereotypes among daters. Race and Social Problems,6(3), 201–213.

Bialik, K. (2017). Key facts about race and marriage, 50 years after Loving. Virginia: Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 12, 2017 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/12/key-facts-about-race-and-marriage-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia/.

Bernstein, M., & Cruz, M. (2009). "What are You?": Explaining identity as a goal of the multiracial hapa movement. Social Problems,56(4), 722–745.

Bonam, C., & Shih, M. (2009). Exploring multiracial individuals’ comfort with intimate interracial relationships. Journal of Social Issues,65(1), 87–103.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies,27(6), 931–950.

Bratter, J. (2007). Will “multiracial” survive to the next generation?: The racial classification of children of multiracial parents. Social Forces, 86(2), 821–849.

Brunsma, D., Delgado, D., & Rockquemore, K. A. (2013). Liminality in the multiracial experience: Towards a concept of identity matrix. Identities,20(5), 481–502.

Buggs, S. G. (2017). Dating in the time of #blacklivesmatter: exploring mixed-race women’s discourses of race and racism. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity,3(4), 538–551.

Buggs, S. G. (2019). Color, culture, or cousin? Multiracial Americans and framing boundaries in interracial relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12583.

CensusScope. (2014). Multiracial profile. Ann Arbor, MI: Social Science Data Analysis Network. https://www.censusscope.org/us/chart_multi.html.

Chen, J. M., & Hamilton, D. (2012). Natural ambiguities: Racial categorization of multiracial individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,48(1), 152–164.

Cho, S. K. (1997). Converging stereotypes in racialized sexual harassment: Where the model minority meets Suzie Wong. Journal of Gender Race Justice,1, 177.

Chou, R. S. (2012). Asian American sexual politics: The construction of race, gender, and sexuality. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Colby, S. L., Ortman, J. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. US Census Bure. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf.

Collins, P. H. (2004). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge.

Coontz, S. (2006). Marriage, a history: How love conquered marriage. New York: Penguin.

Cox, O. C. (1948). Caste, class and race: A study in social dynamics. Garden City: Doubleday and Company.

Curington, C. V. (2020). “We're the show at the circus”: Racially dissecting the multiracial body. Symbolic Interaction. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/symb.484.

Curington, C. V., Ken-Hou L., & Jennifer H. L. (2015). Positioning multiraciality in cyberspace: Treatment of multiracial daters in an online dating website. American Sociological Review, 80(4), 764–788.

DaCosta, K. M. (2007). Making multiracials: State, family, and market in the redrawing of the color line. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Davenport, L. (2016). Beyond black and white: Biracial attitudes in contemporary US politics. American Political Science Review,110(1), 52–67.

Davis, F. J. (2010). Who is Black? One nation's definition. University Park: Penn State University Press.

Doyle, J. M., & Kao, G. (2007). Friendship choices of multiracial adolescents: Racial homophily, blending, or amalgamation? Social Science Research,36(2), 633–653.

Feliciano, C., Lee, R., & Robnett, B. (2011). Racial boundaries among Latinos: Evidence from internet daters' racial preferences. Social Problems,58(2), 189–212.

Feliciano, C., Robnett, B., & Komaie, G. (2009). Gendered racial exclusion among White internet daters. Social Science Research,38(1), 39–54.

Gans, H. J. (1999). The possibility of a new racial hierarchy in the twenty-first century United States. In M. Lamont (Ed.), The cultural territories of race: Black and White boundaries (pp. 371–390). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gans, H. J. (2012). “Whitening” and the changing American racial hierarchy. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race,9(2), 267–279.

Garcia, A., Riggio, H. R., Palavinelu, S., & Culpepper, L. L. (2012). Latinos’ perceptions of interethnic couples. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,34, 349–362.

Gordon, L. (1997). Her majesty’s other children: Sketches of racism from a neocolonial age. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gullickson, A., & Morning, A. (2011). Choosing race: Multiracial ancestry and identification. Social Science Research,40(2), 498–512.

Hanley, J. A., Negassa, A., & Forrester, J. E. (2003). Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology,157(4), 364–375.

Harris, D. R., & Sim, J. (2000). An empirical look at the social construction of race: The case of multiracial adolescents. https://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/pubs/pdf/rr00-452.pdf.

Herman, M. R. (2010). Do you see what I am? How observers’ backgrounds affect their perceptions of multiracial faces. Social Psychology Quarterly,73(1), 58–78.

Ho, A. K., Kteily, N., & Chen, J. (2017). “You’re one of us”: Black Americans’ use of hypodescent and its association with egalitarianism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,113(5), 753.

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Levin, D. T., & Banaji, M. (2011). Evidence for hypodescent and racial hierarchy in the categorization and perception of biracial individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,100(3), 492.

Hwang, W. (2013). Who are people willing to date? Ethnic and gender patterns in online dating. Race and Social Problems,5(1), 28–40.

Khanna, N. (2010). “If you're half black, you're just black”: Reflected appraisals and the persistence of the one-drop rule. The Sociological Quarterly,51(1), 96–121.

Khanna, N. (2011). Biracial in America: Forming and performing racial identity. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Kim, C. (2018). Are Asians the new blacks?: Affirmative action, anti-blackness, and the ‘sociometry’ of Race’. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race,15(2), 1–28.

Korgen, K. O. (1998). From black to biracial: Transforming racial identity among Americans. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Lee, J. (2015). From undesirable to marriageable: Hyper-selectivity and the racial mobility of Asian Americans. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,662(1), 79–93.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. (2004). America's changing color lines: Immigration, race/ethnicity, and multiracial identification. Annual Review of Sociology,30, 221–242.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. (2007). Reinventing the color line immigration and America's new racial/ethnic divide. Social Forces,86(2), 561–586.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. (2010). The diversity paradox: Immigration and the color line in twenty-first century America. Thousand Oak: Russell Sage Foundation.

Liang, K. -Y., & Scott L. Z. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1),13–22.

Lin, K., & Lundquist, J. (2013). Mate selection in cyberspace: The intersection of race, gender, and education. American Journal of Sociology,119(1), 183–215.

Littlejohn, K. E. (2019). Race and social boundaries: How multiracial identification matters for intimate relationships. Social Currents, 6(2), 177–194.

Livingston, G., & Brown, A. (2017). Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 years after loving v. virginia.” Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 18, 2017 from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/05/18/intermarriage-in-the-u-s-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia/.

Lundquist, J. H., & Lin, K. -H. (2015). Is love (color) blind? The economy of race among gay and straight daters. Social Forces, 93(4), 1423–1449.

Masuoka, N. (2008). Political attitudes and ideologies of multiracial Americans: The implications of mixed race in the United States. Political Research Quarterly,61(2), 253–267.

McGrath, A. R., Tsunokai, G. T., Schultz, M., Kavanagh, J., & Tarrence, J. (2016). Differing shades of colour: Online dating preferences of biracial individuals. Ethnic and Racial Studies,39(11), 1920–1942.

Mishra, S. (2013). Race, religion, and political mobilization: South Asians in the Post-9/11 United States. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism,13(2), 115–137.

Miyawaki, M. H. (2015). Expanding boundaries of whiteness? A look at the marital patterns of part-white multiracial groups. Sociological Forum,30(4), 995–1016.

Muro, J. A., & Martinez, L. M. (2018). Is love color-blind? Racial blind spots and latinas’ romantic relationships. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity,4(4), 527–540.

Newman, A. M. (2017). Desiring the standard light skin: Black multiracial boys, masculinity and exotification. Identities,26(1), 107–125.

Pew Research 2015. (2015). https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/.

Pyke, K. D. (2010). An intersectional approach to resistance and complicity: The case of racialised desire among Asian American women. Special issue women, intersectionality and diasporas. Journal of Intercultural Studies,31(1), 81–94.

Qian, Z. (2004). Options: Racial/ethnic identification of children of intermarried couples. Social Science Quarterly,85, 746–766.

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2007). Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review,72(1), 68–94.

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2011). Changing patterns of interracial marriage in a multiracial society. Journal of Marriage and Family,73(5), 1065–1084.

Rafalow, M. H., Feliciano, C., & Robnett, B. (2017). Racialized femininity and masculinity in the preferences of online same-sex daters. Social Currents,4(4), 306–321.

Roberts-Clarke, I., Angie C. R., & Patricia M. (2004). Dating practices, racial identity, and psychotherapeutic needs of biracial women. Women & Therapy, 27(1-2), 103–117.

Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2011). Patterns of racial-ethnic exclusion by internet daters. Social Forces,89(3), 807–828.

Rockquemore, K. A. (2002). Negotiating the color line: The gendered process of racial identity construction among black/white biracial women. Gender & Society,16(4), 485–503.

Rockquemore, K. A., & Brunsma, D. (2002). Beyond black: Biracial identity in America. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Root, M. P. P. (2004). From exotic to a dime a dozen. Women and Therapy,27(1–2), 19–31.

Roth, W. D. (2005). The end of the one-drop rule? labeling of multiracial children in black intermarriages. Sociological Forum, 20(1), 35–67.

Rudder, C. (2014). Dataclysm. New York: Random House.

Sexton, J. (2008). Amalgamation schemes: AntiBlackness and the critique of multiracialism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stephens, D. P., Fernandez, P. B., & Richman, E. (2013). Ni Pardo, Ni Prieto: The Influence of parental skin color messaging on heterosexual emerging adult White-Hispanic women’s dating beliefs. Feminist therapy with latina women (pp. 15–29). New York: Routledge.

Sims, J. P. (2012). Beautiful stereotypes: The relationship between physical attractiveness and mixed race identity. Identities,19(1), 61–80.

Song, M. (2015). What constitutes intermarriage for multiracial people in Britain? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,662(1), 94–111.

Spickard, P. R. (1991). Mixed blood: Intermarriage and ethnic identity in twentieth-century America. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Treitler, V. B. (2013). The ethnic project: Transforming racial fiction into ethnic factions. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tsunokai, G. T., Kposowa, A. J., & Adams, M. A. (2009). Racial preferences in Internet dating: A comparison of four birth cohorts. Western Journal of Black Studies,33(1), 1.

Vasquez-Tokos, J. (2015). Disciplined preferences: Explaining the (re) production of Latino endogamy. Social Problems,62(3), 455–475.

Vasquez-Tokos, J. (2017). Marriage vows and racial choices. Thousands Oaks, CA: Russell Sage Foundation.

Waring, C. D. (2013). “They see me as exotic… That Intrigues them”: Gender, sexuality and the racially ambiguous body. Race, Gender and Class,1, 299–317.

Waring, C. D. (2017). “It’s like we have an ‘in’ already”: THE racial capital of black/white biracial Americans. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race,14(1), 145–163.

Yancey, G., & Yancey, S. (1998). Interracial dating: Evidence from personal advertisements. Journal of Family Issues,19(3), 334–348.

Zuur, A. F. (2009). Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curington, C.V., Lundquist, J.H. & Lin, KH. Tipping the Multiracial Color-Line: Racialized Preferences of Multiracial Online Daters. Race Soc Probl 12, 195–208 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-020-09295-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-020-09295-z