Abstract

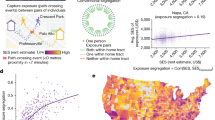

A longstanding finding is that neighborhood racial segregation is linked to violence. In this paper, we look beyond neighborhoods of residence to consider the everyday mobility of urbanites in their daily rounds. Analyzing estimates of neighborhood mobility from largescale social media data in the 50 largest American cities, we find that residential segregation by race is not only associated with higher violence but also lower equitability of travel across neighborhoods and a lower concentration of visits to common hubs. Further, the interaction of equitable and concentrated mobility is significantly associated with rates of violence, controlling for both racial and income segregation, education, city size, and density. There is little evidence, however, that patterns of everyday mobility mediate the influence of residential racial segregation. Both dimensions of the structural connectedness of cities—one rooted in place of residence, and the other encompassing interneighborhood exposure based on travel throughout the metropolis—are implicated in violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Violent crimes include homicide, rape or sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault.

Income category cut points are (in thousands of dollars): 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 60, 75, 100, 125, 150, and 200 plus.

Phillips et al. (2019) assume that each resident of a city is equally important for a neighborhood’s contact with other neighborhoods, and thus each observed resident’s visits are normalized to have an outdegree of one, rendering each resident’s visits to a neighborhood a proportion of their total visits. They also assume that each neighborhood has equal importance in the structural connectedness of a city, thereby normalizing each neighborhood to have an outdegree of 1 by dividing its residents’ aggregated proportions of visits to other neighborhoods by the sending neighborhood’s total number of residents. Finally, they assume that travelers to a city (or tourists) play a different and less important role than residents in the structural connectedness of a city, and so they remove travelers from the calculation of connectedness. This decision aligns with our corresponding focus on the racial segregation of city residents.

Although the share of residents holding a bachelor’s degree is highly correlated with median household income (.79), the educational measure is correlated with equitable mobility at a higher level than median income (.31 vs. .19). We thus use percent of adults with a bachelor’s degree as the main control. The results for our mobility-based predictions of violence are nonetheless very similar when we control for median income instead.

References

Anderson, E. (1990). Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blau, P. M. (1977). Inequality and heterogeneity: A primitive theory of social structure. New York: Free Press.

Blau, J. R., & Blau, P. M. (1982). The cost of inequality: Metropolitan structure and violent crime. American Sociological Review,47, 114–129.

Blau, P. M., & Schwartz, J. E. (1984). Crosscutting social circles: Testing a macrostructural theory of intergroup relations. New York: Academic Press.

Browning, C. R., Calder, C., Solle, B., Jackson, A., & Dirlam, J. (2017). Ecological networks and neighborhood social organization. American Journal of Sociology,122, 1939–1988.

Browning, C. R., & Soller, B. (2014). Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research,16, 165–196.

Firebaugh, G., & Farrell, C. R. (2016). Still large, but narrowing: The sizable decline in racial neighborhood inequality in Metropolitan America, 1980–2010. Demography,53, 139–164.

Graif, C., Freelin, B. N., Kuo, Y.-H., Wang, H., Li, Z., & Kifer, D. (2019). Network spillovers and neighborhood crime: A computational statistics analysis of employment-based networks of neighborhoods. Justice Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.07412019.01602160.

Krivo, L. J., Peterson, R. D., & Kuhl, D. C. (2009). Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. American Journal of Sociology,114(6), 1765–1802.

Krivo, L. J., Washington, H. M., Peterson, R. D., Browning, C. R., Calder, C. A., & Kwan, M.-P. (2013). Social isolation of disadvantage and advantage: The reproduction of inequality in urban space. Social Forces,92, 141–164.

Le Roux, G., Vallée, J., & Commenges, H. (2017). Social segregation around the clock in the Paris region (France). Journal of Transport Geography,59, 134–145.

Lichter, D. T., Parisi, D., & Taquino, M. C. (2015). Toward a new macro-segregation? Decomposing segregation within and between metropolitan cities and suburbs. American Sociological Review,80, 843–873.

Light, M. T., & Thomas, J. T. (2019). Segregation and violence reconsidered: Do whites benefit from residential segregation? American Sociological Review,84, 690–725.

Massey, D. S. (1990). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. American Journal of Sociology,96(2), 329–357.

Massey, D. S. (1995). Getting away with murder: Segregation and violent crime in urban America. University of Pennsylvania Law Review,143, 1203–1232.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Palmer, J. R., Espenshade, T. J., Bartumeus, F., Chung, C. Y., Ozgencil, N. E., & Li, K. (2013). New approaches to human mobility: Using mobile phones for demographic research. Demography,50, 1105–1128.

Peterson, R. D., & Krivo, L. J. (2005). Macrostructural analyses of race, ethnicity, and violent crime: Recent lessons and new directions for research. Annual Review of Sociology,31(1), 331–356.

Peterson, R. D., & Krivo, L. J. (2010). Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Phillips, N., Levy, B. L., Sampson, R. J., Small, M. L., & Wang, R. Q. (2019). The social integration of American cities: Network measures of connectedness based on everyday mobility across neighborhoods. Sociological Methods and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119852386.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and renewal of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Reardon, S. F., & Bischoff, K. (2011). Income inequality and income segregation. American Journal of Sociology,116, 1092–1153.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science,277, 918–924.

Sampson, R. J., & Wilson, W. J. (1995). Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality. In J. Hagan & R. D. Peterson (Eds.), Crime and inequality (pp. 37–56). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Wang, R. Q., Phillips, N., Small, M., & Sampson, R. J. (2018). Urban mobility and neighborhood isolation in America’s 50 largest cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,115(30), 7735–7740.

Wikström, P.-O. H., Ceccato, V., Hardie, B., & Treiber, K. (2010). Activity fields and the dynamics of crime: advancing knowledge about the role of the environment in crime Causation. Journal of Quantitative Criminology,26, 55–87.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Funding

Funding was provided in part by the National Science Foundation Grants SES- #1637136 and SES #1735505.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: OLS Regression Models of 2016 Log Violent Crime Rate per 100,000 Population (n = 49)

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Racial segregation | 3.128*** [0.665] | 2.867*** [0.634] | 3.230*** [0.659] | 2.607*** [0.695] | |||

Income segregation | 3.445 [2.942] | 2.79 [3.407] | 5.392 [3.282] | ||||

% BA | − 1.603* [0.639] | − 0.302 [0.551] | − 0.244 [1.269] | 0.208 [1.264] | |||

ln(population) | − 0.185+ [0.104] | − 0.210* [0.0945] | − 0.350** [0.123] | − 0.401** [0.122] | |||

ln(pop. density) | 0.175* [0.066] | − 0.001 [0.069] | − 0.000 [0.056] | 0.083 [0.058] | |||

Equitable mobility | − 3.953 [2.797] | − 2.497 [1.787] | − 7.395* [2.802] | ||||

Concentrated mobility | 1.059 [3.416] | − 4.141** [1.538] | − 3.363 [3.156] | ||||

Eq. mobility * conc. mobility | 120.9** [35.31] | 132.8** [41.35] | 101.1* [39.18] | ||||

Constant | 5.763*** [0.215] | 5.283*** [0.518] | 8.366*** [1.363] | 8.263*** [1.411] | 9.906*** [1.460] | 6.669*** [0.0653] | 11.41*** [1.618] |

R 2 | 0.336 | 0.359 | 0.153 | 0.431 | 0.558 | 0.235 | 0.333 |

AIC | 53.79 | 54.07 | 69.77 | 54.27 | 47.85 | 64.75 | 64.02 |

Appendix B: OLS Regression Models of 2016 Log Homicide Rate Per 100,000 Population (n = 50)

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black–white exposure index | − 2.595*** [0.415] | − 2.460*** [0.461] | − 3.459*** [0.481] | − 3.221*** [0.385] | |||

Income segregation | 3.89 [3.160] | − 1.364 [3.087] | 1.203 [2.169] | ||||

% BA | − 3.361** [1.153] | − 1.137 [0.701] | − 0.311 [1.676] | 1.731 [2.029] | |||

ln(population) | − 0.296+ [0.172] | − 0.261* | − 0.500*** [0.105] | − 0.606** [0.176] | |||

ln(pop. density) | 0.251* [0.103] | − 0.254* [0.103] | − 0.285*** [0.0701] | 0.041 [0.078] | |||

Equitable mobility | − 6.554* [2.788] | − 4.373+ [2.299] | − 13.17*** [3.518] | ||||

Concentrated mobility | 0.13 [4.015] | − 10.47*** [2.021] | − 11.99** [4.240] | ||||

Eq. mobility * conc. mobility | 140.8*** [32.73] | 168.6*** [44.72] | 119.0** [41.27] | ||||

Constant | 3.440*** [0.210] | 2.757*** [0.652] | 5.528* [2.341] | 9.975*** [1.747] | 12.69*** [1.465] | 2.321*** [0.091] | 9.667*** [2.320] |

R 2 | 0.514 | 0.526 | 0.207 | 0.704 | 0.799 | 0.345 | 0.438 |

AIC | 82.58 | 83.29 | 111.00 | 65.75 | 52.41 | 101.40 | 99.77 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sampson, R.J., Levy, B.L. Beyond Residential Segregation: Mobility-Based Connectedness and Rates of Violence in Large Cities. Race Soc Probl 12, 77–86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-019-09273-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-019-09273-0