Abstract

Objectives

The current study examines the percentage of a state’s total expenditures that is allocated for corrections in an attempt to untangle how the influence of key determinants helped to shift state resources in ways likely to aid prison expansion. This study further attempts to address how the salience of crime, partisan politics, and racial and social threats may have shifted over time and across regions.

Methods

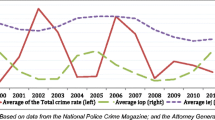

The study employs a pooled time-series analysis of 49 states from 1971 through 2008, with a final sample size of N = 1862 cases, to examine the factors that help to predict the log-transformed percent of total state expenditures allocated for the total direct expenditures on corrections.

Results

The current study finds that determinants of state-level corrections spending vary across time. Violent crime had a positive and significant influence on corrections spending during the 80s, while Republican strength was similarly associated with increases in spending from the 80s through the 90s. Further, beginning in the 80s, percentage African-American were negatively associated with the proportion of budget allocated for corrections.

Conclusions

The findings presented in this study emphasize the importance of time and place when trying to untangle trends in correctional budget decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Campbell et al. (2015) found that the percentage of Hispanics and Republican strength influence state-level incarceration rates in Sunbelt states, while having no significant impact in non-Sunbelt states. Relatedly, the percentage of non-Hispanic blacks and political ideology significantly impact incarceration in non-Sunbelt states, while having no statistically significant relationship with incarceration rates in Sunbelt states.

Corrections expenditures were log-transformed to minimize skewness of the distribution across states.

Data were not available for state expenditures for the years 2002 and 2004, so the missing data were linearly interpolated. Supplementary analyses were conducted with the interpolated data excluded, and the results were nearly identical with all significant predictors remaining the same. These analyses are available upon request.

Electoral year and presidential party have been argued to influence incarceration rates (see Smith 2004); however, they have not been shown to influence spending on corrections (see Stucky et al. 2007). Both measures were included in preliminary analyses, but were excluded from the final models since they failed to reach significance and had no impact on other significant variables.

Since this measure is not very intuitive, a more nuanced computation is provided.

Citizen Ideologyd,t = (Proportion of electorate preferring incumbentd,t)(Ideology score of imcumbentd,t) + (Challenger proportion of the electorated,t)(Challenger ideology scored,t), in which d denotes the district and t denotes the year. Each district’s ideological score is than combined to generate the un-weighted average.

State-level Citizen Ideologyt = (Citizen Ideology(Sum)d)/d).

The quadratic term for Black Squared was excluded from the time-specific models after preliminary results found that this relationship was no longer significant and had no impact on other relevant significant predictors.

Many punishment scholars suggest that national level forces, such as court-ordered prison reform, help to shape state-level penal policy, in turn leading to increases in incarceration rates. For example, Heather Schoenfeld (2010) found that court-ordered prison reform to reduce prison populations in Florida led to the building of new prisons to reduce prison overcrowding, eventually backfiring and resulting in increased incarceration numbers. Taggart (1989) and Fliter (1996), on the contrary, argue that the federal judiciary has a limited role in shaping state correctional operating expenditures. It is suggested that “spending is shaped in large measure by forces much more compelling and forceful than a single discrete event such as a court order” (Taggart 1989, p. 268). Despite this argument, the current models include a measure of federal aid in an attempt to capture how national level forces, such as the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, may have influenced state-level budgetary decisions. However, it is impossible to determine what the federal aid is spent on within the state, as it is just an aggregated measure of all funds given to the state.

Region fixed-effects, rather than state fixed-effects, were used to gain a better understanding of how state-level punishment decisions may group together by regional location, as argued to be the case by prior scholars (Zimring and Hawkin, 1991). However, alternative models were run including state-level fixed-effects. Statistically significant relationships remained stable, and state-level fixed-effects do not appear to be significant after controlling for the panel-specific correlation structure and region, and are therefore left out of the models. Supplemental analyses are available upon request.

Diagnostics show that the inclusion of an AR(1) term eliminated the serial correlation within the models, with rho estimates nearing zero.

A more detailed list of the sources is available upon request.

When the lagged dependent variable is removed from Model 1, for example, the R-squared drops from .95 to .37, suggesting that previous year spending on corrections is the strongest predictor of current year’s spending.

Percentage change in state GDP was also included in later models to measure the temporal changes, however, the results suggest that the impact of growth in state GDP in subsequent time periods was no different than in 1970. This result suggests that steady growth in GDP followed along with steady growth in correctional budgetary decisions. In other words, the two variables are highly correlated (p < .001).

The only variable that has an alternative interpretation is the log-transformed previous year’s spending. This variable is interpreted as a one percent increase in previous year’s spending is associated with a coefficient percent increase in current year spending.

Wald tests were conducted on the final Model (Model 2 of Table 3) to provide the F-statistic for the variables used, including the time-specific interaction variables. For the interaction terms, violent crime (F = 45.25***) and republican strength (F = 19.42***) were statistically significant, while percentage black (F = 4.84), unemployment (F = 8.84), and citizen ideology (F = 1.53) failed to reach significance. The remainder of the variables—property crime (F = 0.36), ages 18–24 (F = 2.08), federal aid (F = 2.67), percentage change in income (F = 0.21), determinate sentencing (F = 0.11), and population (F = 2.47)—failed to reach significance with the exception of percentage change GDP (F = 4.20*).

The authors analyzed region-specific models to gain better insight into how these factors may vary across region. Two key findings emerge. First, result suggest that the South is primarily responsible for the influx in corrections spending during the 1970s, with political partisanship having little effect. Following, republican strength across the remaining regions was significantly associated with increased spending on corrections, relative to the 1970s. These supplemental analyses are available from the corresponding author upon request.

It should be noted that supplemental models were conducted using more specific and shorter times periods (5-year blocks as compared to the current decade blocks), and results were little changed. The supplemental analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.

From 1960 to 1975, many Southern states with large proportions of African Americans had double digit increases in incarceration rates. For example, Georgia experienced a 22 percent increase in incarceration over this time period, while North and South Carolina faced increases of 58 percent and 151 percent, respectively.

References

Alexander M (2012) The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press, New York

Aviram H (2015) Cheap on crime: Recession-era politics and the transformation of American punishment. University of California Press, Berkeley

Baltagi B (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data, 4th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Baumer EP, Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (2003) Explaining spatial variation in support for capital punishment: a multilevel analysis. Am J Sociol 108(4):844–875

Beck NL, Katz JN (1995) What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. Am Polit Sci Rev 89(3):634–647

Beckett K (1999) Making crime pay: law and order in contemporary American politics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Behrens A, Uggen C, Manza J (2003) Ballot manipulation and the “Menace of Negro Domination”: Racial threat and felon disenfranchisement in the United States, 1850–2002. Am J Sociol 109(3):559–605

Berry WD, Ringquist EJ, Fording RC, Hanson RL (1998) Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American states, 1960-93. Am J Polit Sci 42(1):327–348

Breunig C, Ernst R (2011) Race, inequality, and the prioritization of corrections spending in the American States. Race Justice 1(3):233–253

Caldeira GA, Cowart AT (1980) Budgets, institutions, and change: criminal justice policy in America. Am J Polit Sci 24(3):413–438

Campbell MC (2011) Politics, prisons, and law enforcement: an examination of the emergence of “law and order” politics in Texas. Law Soc Rev 45(3):631–665

Campbell MC, Schoenfeld H (2013) The transformation of America’s penal order: a historicized political sociology of punishment. Am J Sociol 118(5):1375–1423

Campbell MC, Vogel M, Williams JH (2015) Historical contingencies and the evolving importance of race, violent crime and region in explaining mass incarceration in the United States. Criminology 53(2):180–203

Currie E (1998) Crime and punishment in America. Picador, New York

Davey JD (1998) The politics of prison expansion: winning elections by waging war on crime. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport

Drukker DM (2003) Testing for serial correlation in linear panel-data models. Stata J 3(2):168–177

Dye RF, McGuire TJ (1992) Sorting out state expenditure pressures. Nat Tax J 45(3):315–329

Elling RC (1983). State bureaucracies. In: Gray V, Jacob H, Vines K (eds) Politics in the American States: a comparative analysis (4th edn). Little, Brown, Boston

Ellwood JW, Guetzkow J (2009) Footing the bill: causes and budgetary consequences of state spending on corrections. In: Raphael S, Stoll MA (eds) Do prisons make us safer? The benefits and costs of the prison boom. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 207–238

Enns PK (2013) Punitive politics in the U.S. States. In: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago

Farrington DP (1986) Age and crime. Crime Justice 7:189–250

Feeley MM, Rubin EL (1998) Judicial policy making and the modern state. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fliter J (1996) Another look at the judicial power of the purse: courts, corrections, and state budgets in the 1980s. Law Soc Rev 30(2):399–416

Garand JC, Hendrick RM (1991) Expenditure tradeoffs in the American States: a longitudinal test, 1948–1984. West Polit Quart 44(4):915–940

Garland D (1990) Punishment and modern society: a study in social theory. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Garland D (2004) Crime control and social order. In: Kraska PB (ed) Theorizing criminal justice. Waveland Press Inc, Long Grove, pp 286–301

Garland D (2013) Penality and the penal state. Criminology 51(3):475–517

Gilmore Ruth Wilson (2007) Golden Gulag: prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in Globalizing California. University of California Press, Berkeley

Glaze LE, Maruschak LM (2008) Parents in prison and their minor children. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington DC

Gottschalk M (2014) Caught: the prison state and the lockdown of American politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Gray V, Hanson RL, Kousser T (2012) Politics in the American states: a comparative analysis. CQ Press, Washington, DC

Greenberg DF, West V (2001) State prison populations and their growth, 1971–1991. Criminology 39(3):615–654

Haney Lopez I (2015) Dog whistle politics: how coded racial appeals have reinvented racism and wrecked the middle class. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Jackson PI (1989) Minority group threat, crime, and policing: Social context and social control. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport

Jackson PI, Carroll L (1981) Race and the war on crime: the sociopolitical determinants of municipal police expenditures in 90 non-southern US cities. Am Sociol Rev 290–305

Jacobs D, Carmichael JT (2001) The politics of punishment across time and space: a pooled time-series analysis of imprisonment rates. Soc Forces 80(1):61–89

Jacobs D, Helms R (1999) Collective outbursts, politics, and punitive resources: toward a political sociology of spending on social control. Soc Forces 77(4):1497–1523

Jacobs D, Jackson AL (2010) On the politics of imprisonments: a review of systematic findings. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 6:129–149

Kirchhoff SM (2010) Economic impacts of prison growth. DIANE Publishing, Darby

Klarner C (2011). Klarner Politics. StatePartisanBalance1934to2011_SourceFiles__05_24. Retrieved 16 April 2014, from Indiana State University http://www.indstate.edu/polisci/klarnerpolitics.htm

Kovandzic TV, Vieraitis LM (2006) The effect of county-level prison population growth on crime rates. Criminol Public Policy 5(2):213–244

Kyckelhahn T (2012) State corrections expenditures, FY 1982-2010. Bureau of Justice Statistics

Liska AE (1992) Social threat and social control. SUNY Press, Albany

Lowenthal GT (1993) Mandatory sentencing laws: undermining the effectiveness of determinate sentencing reform. Calif Law Rev 81(1):61–123

Miller JG (1996) Search and destroy: Black males in the criminal justice system. Cambridge University Press, New York

Newman WJ, Scott CL (2012) Brown v. Plata: prison overcrowding in California. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law Online 40(4):547–552

Painter G, Bae K (2001) The changing determinants of state expenditure in the United States: 1965–1992. Public Finance Manag 1(4):370–392

Pettit B, Western B (2004) Mass imprisonment and the life course: race and class inequality in US incarceration. Am Sociol Rev 69(2):151–169

Pew Center on the States (2009) One in 31: The Long Reach of American corrections. The Pew Charitable Trusts, Washington

Pfaff JF (2017) Locked in: the true causes of mass incarceration and how to achieve real reform. Basic Books, New York

Raphael S, Winter-Ebmer R (2001) Identifying the effect of unemployment on crime. J Law Econ 44(1):259–283

Rusche G, Kirchheimer O (1939) Punishment and social structure. Transaction Publishers, Piscataway

Schoenfeld H (2010) Mass incarceration and the paradox of prison conditions litigation. Law Soc Rev 44(3–4):731–768

Schoenfeld H (2018) Building the prison state: race and the politics of mass incarceration. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Simon J (2007) Governing through crime: how the war on crime transformed american democracy and created a culture of fear. Oxford University Press, New York

Smith KB (2004) The politics of punishment: evaluating political explanations of incarceration rates. J Polit 66(3):925–938

Spelman W (2009) Crime, cash, and limited options: explaining the prison boom. Criminol Public Policy 8(1):29–77

Spelman W (2013) Prisons and crime, backwards in high heels. J Quant Criminol 29(4):643–674

Stemen D, Rengifo AF (2011) Policies and imprisonment: the impact of structured sentencing and determinate sentencing on state incarceration rates, 1978–2004. Justice Q 28(1):174–201

Stemen D, Rengifo A, Wilson J (2005) Of fragmentation and ferment: the impact of state sentencing policies on incarceration rates, 1975–2002. Vera Institute of Justice, New York

Stucky TD, Heimer K, Lang JB (2005) Partisan politics, electoral competition and imprisonment: an analysis of states over time. Criminology 43(1):211–248

Stucky TD, Heimer K, Lang JB (2007) A bigger piece of the pie? State corrections spending and the politics of social order. J Res Crime Delinquency 44(1):91–123

Taggart WA (1989) Redefining the power of the federal judiciary: the impact of court-ordered prison reform on state expenditures for corrections. Law Soc Rev 23(2):241–271

Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1414 (1994)

Western B (2006) Punishment and inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge

Zimring FE (2010) The scale of imprisonment in the United States: twentieth century patterns and twenty-first century prospects. J Crim Law Criminol 100(3):1225–1246

Zimring FE, Hawkins G (1991) The scale of imprisonment. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, J.H., Campbell, M. Exploring the Time-Varying Determinants of State Spending on Corrections. J Quant Criminol 37, 671–692 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09460-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09460-y