Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact of proactive police response on residential burglary and theft from vehicle in micro-time hot spots as well as whether spatial displacement occurs.

Methods

Over 2 years, 114 treatment and 103 control micro-time hot spots were assigned to groups using “trickle-flow” randomization. Responses were implemented as part of the police department’s established practices, and micro-time hot spots were blocked based on their temporal proximity—sprees or ongoing. The study was blinded and tested proactive patrol versus a no-dosage control condition.

Results

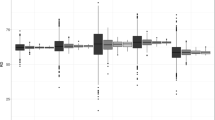

The department responded to each micro-time hot spot with, on average, five 20-min responses per day for 19 days. Eighty percent of the response time involved conducting directed patrol without encountering suspicious activity. Results show that treatment micro-time hot spots had significantly fewer crimes after 15 days (79%) and 30 days (74%). Treatment effects were greatest in the first 15 days (1.15) followed by days 16–30 (.83).

Conclusions

The study examines a real-world strategy institutionalized into the day-today operations of a police department. The largest impact on crime was seen during response. In addition, crime reductions that occurred while micro-time hot spots received response held for 2 months after the responses end with no evidence of spatial displacement. Our findings reveal larger effect sizes than most hot spots policing studies which may be due to how the unit of analysis was defined, the systematic nature of the response implementation, and the use of a no-dosage, blind control condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Stratified policing is an organizational model for carrying out proactive problem-based, placed-based, offender-based, and community-based activities as part of the day-to-day business of the police organization. The primary goal is to systematize implementation and sustain proactive crime reduction practices by providing a framework for processes similar to the institutionalized process of answering calls for service. For more information see, Santos and Santos (2020).

More detail on this process is provided in the treatment fidelity section.

The study was conducted pro bono by the researchers as well as the police department in that no one or entity received external funding for time or resources spent to carry out the research.

The department serves the city of Port St. Lucie, Florida which is located along the southeast coast. The city’s population in 2015 was around 175,000 with over 120 square miles. As of July 2015, there were 224 authorized sworn and 65 civilian positions and the property crime rate in 2014 and 2015 was 1449 and 1364 per 100,000, respectively.

Similar to Sherman and Rogan’s (1995) experiment on drug houses.

No one else but the analysts and researchers saw the control bulletins.

Interestingly, over the two years of the study, there were only three times in which someone identified a micro-time hot spot on their own. In these cases, the crime analyst released the bulletin for response and the micro-time hot spot was not included in the experiment.

Note that the time spent by detectives investigating each micro-time hot spot and linking them through evidence, arrests, or property is not included here, because that is difficult to measure and is more reactive to the nature of the information and evidence available for each micro-time hot spot.

References

Ariel B, Vila J, Sherman L (2012) Random assignment without tears: how to stop worrying and love the Cambridge randomizer. J Exp Criminol 8:193–208

Ariel B, Sherman LW, Newton M (2020) Testing hot-spots police patrols against no-treatment controls: temporal and spatial deterrence effects in the London underground experiment. Criminology 58:101–128

Austin R, Cooper G, Gagnon D, Hodges J, Martensen K, O’Neal M (1973) Police crime analysis unit handbook. U S Department of Justice National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Washington, DC

Bernasco W (2008) Them again? Same-offender involvement in repeat and near repeat burglaries. Eur J Criminol 5:411–431

Bernasco W (2010) A sentimental journey to crime: effects of residential history on crime location choice. Criminology 48:389–416

Bernasco W, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) How do residential burglars select target areas? A new approach to the analysis of criminal location choice. Br J Criminol 44:296–315

Bowers KJ, Johnson SD (2005) Domestic burglary repeats and space–time clusters: the dimensions of risk. Eur J Criminol 2:67–92

Braga AA, Turchan B, Papachristos AV, Hureau DM (2019) Hot spots policing of small geographic areas effects on crime. Campbell Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1046

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Eck J, Chainey S, Cameron J, Leitner M, Wilson R (2005) Mapping crime: understanding hot spots. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

Gallager K, Wartell J, Gwinn S, Jones G, Stewart G (2017) Exploring crime analysis. International Association of Crime Analysts, Overland Park

Gorr WL, Lee YJ (2015) Early warning system for temporary crime hot spots. J Quant Criminol 31:25–47

Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FE, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, Zafft KM (2015) Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: next generation. Prev Sci 16:893–926

Groff E, Taniguchi T (2019) Quantifying crime prevention potential of near-repeat burglary. Police Q. https://doi.org/10.1177/10986111198280521-30

Groff ER, Ratcliffe JH, Haberman CP, Sorg ET, Joyce NM, Taylor RB (2015) Does what police do at hot spots matter? The Philadelphia policing tactics experiment. Criminology 53:23–53

Haberman CP (2016) A view inside the ‘‘Black Box’’ of hot spots policing from a sample of police commanders. Police Q 19:488–517

Hoover L, Wells W, Zhang Y, Ren L, Zhao J (2016) Houston enhanced action patrol: examining the effects of differential deployment lengths with a switched replication design. Justice Q 33:538–563

Johnson D (2013) The space/time behaviour of dwelling burglars: finding near repeat patterns in serial offender data. Appl Geogr 4:139–146

Johnson SD, Summers L, Pease K (2007) Vehicle crime: communicating spatial and temporal patterns. Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, London

Johnson SD, Lab S, Bowers KJ (2008) Stable and fluid hot spots of crime: differentiation and identification. Built Environ 34:32–46

Johnson SD, Summers L, Pease K (2009) Offenders as forager: a direct test of the boost account of victimization. J Quant Criminol 25:181–200

Johnson SD, Tilley N, Bowers KJ (2015) Introducing EMMIE: an evidence rating scale to encourage mixed-method crime prevention synthesis reviews. J Exp Criminol 11:459–473

McLaughlin LM, Johnson SD, Bowers KJ, Birks DJ, Pease K (2007) Police perceptions of the long- and shortterm spatial distribution of residential burglary. Int J Police Sci Manag 9:99–111

National Institute of Justice (2018) Program profile: tactical police responses to micro-time hot spots for thefts from vehicles and residential burglaries (Port St. Lucie, Florida). Profile posted on November 13, 2018 to https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=626

O’Shea TC, Nicholls K (2003) Police crime analysis: a survey of U.S. police departments with 100 or more sworn personnel. Police Pract Res 4:233–250

Ratcliffe JH (2009) Near repeat calculator (version 1.3). Temple University, Philadelphia

Sagovsky A, Johnson SD (2007) When does repeat burglary victimisation occur? Aust N Z J Criminol 40:1–26

Santos RG (2013) A quasi-experimental test and examination of police effectiveness in residential burglary and theft from vehicle micro-time hot spots. Dissertation. Nova Southeastern University

Santos RB (2017) Crime analysis with crime mapping. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Santos RB, Santos RG (2015a) Examination of police dosage in residential burglary and theft from vehicle micro-time hots spots. Crime Sci 4:1–12

Santos RG, Santos RB (2015b) An ex post facto evaluation of tactical police response in residential theft from vehicle micro-time hot spots. J Quant Criminol 31:679–698

Santos RG, Santos RB (2015c) Practice-based research: ex post facto evaluation of evidence-based police practices implemented in residential burglary micro-time hot spots. Eval Rev 39:451–479

Santos RG, Santos RB (2020) Stratified policing: an organizational model for proactive crime reduction. Rowman & Littlefield, Landham

Santos RB, Taylor B (2014) The integration of crime analysis into police patrol work: results from a national survey of law enforcement. Policing 37:501–520

Sherman LW (1990) Police crackdowns: initial and residual deterrence. Crime Justice 12:1–48

Sherman LW, Rogan D (1995) Deterrent effects of police raids on crack houses: a randomized controlled experiment. Justice Q 12:755–782

Sullivan GM, Feinn R (2012) Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ 4:279–282

Telep CW, Mitchell RJ, Weisburd DL (2014a) How much time should the police spend at crime hot spots? Answers from a police agency directed randomized field trial in Sacramento. Calif Justice Q 31:905–933

Telep CW, Weisburd D, Gill CE, Vitter Z, Teichman D (2014b) Displacement of crime and diffusion of crime control benefits in large-scale geographic areas: a systematic review. J Exp Criminol 10:515–548

Wain N, Ariel B (2014) Tracking of police patrol. Policing 8:274–283

Weisburd D, Gill C (2014) Block randomized trials at places: rethinking the limitations of small N experiments. J Quant Criminol 30:97–112

Weisburd D, Majmundaar MK (eds) (2018) Proactive policing: effects on crime and communities. The National Academies Press, Washington DC

Weisburd D, Groff ER, Yang S-M (2012) The criminology of place: street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, R.B., Santos, R.G. Proactive Police Response in Property Crime Micro-time Hot Spots: Results from a Partially-Blocked Blind Random Controlled Trial. J Quant Criminol 37, 247–265 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09456-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09456-8