Abstract

We estimate the effects of a debit card incentive program on consumer behavior using bank-recorded transaction micro data and a natural experiment design. Using geographic and eligibility features of a generous pilot program offered by a Midwestern regional bank, we estimate both difference in difference and regression discontinuity models, allowing us to identify changes in debit and cash usage resulting from the program. Our primary results show that the program increases the number of debit transactions per customer by between 18.8 and 20.4%. We also estimate that cash usage declines, although these estimates are not statistically significant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

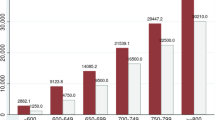

The 2016 Federal Reserve report highlights that non-prepaid debt transactions grew from 47.3 billion transactions, valued at $1.87 trillion in 2012 to 59.6 billion transactions valued at $2.29 trillion in 2015. Credit Card transactions crew from 26.8 billion transactions valued at $2.55 trillion in 2012 to 33.8 billion transactions valued at $3.16 trillion in 2016.

The Federal Reserve of Philadelphia, Consumer Finance Institute reports an increase of only 9 million debit card holders between 2012 and 2015, from a base of 191 million, and growth of only 3 million debit card holders between 2014 and 2015 from a base of 197 million.

Debit cards only represent 2.56% of the value of all non-cash transactions, indicating that increasing the value of transactions is another potential area for growth (Federal Reserve System 2016).

There is also a literature examining how factors like advertising affect card use. See Jonker et al. (2017) for a recent example examining a public campaign to increase debit card usage in the Netherlands.

There is also evidence suggesting that using cash is associated with crime (Foley (2011); Armey et al. (2014), Wright et al. (2017)), so if rewards programs cause consumers to switch to debit card use as a cash replacement, these programs may have broader benefits to society. We do not find an association between the program and cash withdrawals in the work presented here, but it is at least a plausible benefit.

See Angrist and Pischke (2009) for a complete description of how “bad controls” can induce the included variable bias problem.

An exception to meeting the 10 transactions threshold was given for customers who met one of three other criteria. These were a) the presence of an overdraft fee waiver product that lowered the price of some overdraft fees from $37 to $7 in exchange for a monthly fee of $10, b) a specialty loan product intended to improve a customer’s credit score, or c) direct deposits of over $500 in that statement period. If any of these three criteria were met by the customer, even if the 10-transaction criterion was not met, the fee was waived. 43% of Incentive Checking Accounts opened during the pilot period qualified for a waived fee for the reasons listed above.

Importantly, for identification purposes the pilot branches were not chosen because of customer or employee characteristic difference that may affect the outcomes we study. The pilot program was implemented at these branches simply to ensure that State Bank’s internal computing system was operationally compatible with program’s incentives. We were able to test the difference in the third party credit score between treated and comparison branches. Customers at treated branches have a slightly lower score on average (503 vs. 514), but a difference in means t-test suggests this difference is not statistically different than zero. Additional pre-treatment outcome comparisons can be found in Table I.

We also considered using triple difference identification, relying on the difference between Universal and Incentive/Free Account customers across branches that do and do not start the Incentive Checking program on December 1st. We determined that this comparison suffered from high variance in outcomes among Universal account holders, due to small numbers of customers in this category at some branches during this time period.

We considered using a triple difference estimator that compared customers across treated and comparison branches, time, and the credit score cut-off. This identification strategy ultimately relied on too few observations within groups, so we decided it was not reliable.

We cannot use a finer time period for aggregation of transactions due to restrictions on the data that State Bank is willing allow us to use under a data sharing agreement.

State Bank’s incentive structure for branch employees encouraged sales at different times throughout the period we examine. Attempting to meet incentive goals plausibly led to new accounts on higher volume days having a lower propensity to be active account users; the time varying branch measure attempts to control for this effect and isolate it from treatment effects.

Some customers are assigned a null score because they do not have a history of checking account use. If a null score is assigned by the third-party credit scoring system, State Bank uses other factors to determine account eligibility. Accounts opened by these customers are excluded from the treatment group.

We also estimated difference in difference models for the propensity of accounts to use a loan product and for the accounts to overdraft. These results show a fairly large (5.4%) reduction in the probability of overdraft, and a fairly small (2.7%) increase in the probability of using a loan product from State Bank. Across the range of specifications, these results have large standard errors relative to the point estimate, and we therefore do not draw any strong conclusions from these estimates.

Ratios are generated using regressions with the amount of cash withdrawn from accounts, not the natural log results presented in Table 3. These results, available by request, suggest negative effects on cash withdrawals, but like the natural log results they are not statistically significant in any specification.

In an attempt to obtain more consistent estimates of withdrawals and the dollar amount of withdrawals, we estimated specifications using a natural log transformation of these variables. These specifications yielded no difference in the statistical significance of the results.

The cash amount of withdrawals was statistically insignificant in these estimations and, as it was also insignificant in (1), (2) and (3) we chose to omit it from this table.

A low activity customer is defined as having fewer than 10 total transactions (including debit, withdrawals, transfers, and other behaviors), no direct deposits, no overdraft fee reduction product, and no specialty loan product.

Note that this cost benefit analysis does not include the potential for the debit incentive to have spillover effects on other aspects of State Bank’s business. We were not able to definitively find any spillover effects from the debit incentive program, but some of our empirical work suggests that the program had a negative effect on the propensity for customers to overdraft and a positive effect on the propensity for customers to use loan products at State Bank.

References

Angrist J, Pischke J-S (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an Empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Arango C, Huynh K, Sabetti L (2015) Consumer payment choice: merchant card acceptance versus pricing incentives. J Bank Financ 55:130–141

Armey L, Lipow J, Webb N (2014) The impact of electronic financial payments on crime. Inf Econ Policy 29:46–57

Calonico S, Cattaneo M, Titiunik R (2014a) Robust data-driven inference in the regression-discontinuity design. Stata J 14(4):909–946

Calonico S, Cattaneo M, Titiunik R (2014b) Robust non-parametric confidence intervals for regression discontinuity designs. Econometrica 82(6):2295–2326

Carbó-Valverde S, Linares-Zegarra J (2011) How effective are rewards programs in promoting payment card usage? Empirical evidence. J Bank Financ 35:3275–3291

Carbó-Valverde S, Humphrey DB, Lopez del Paso R (2003) The falling share of cash payments in Spain. Moneda y Crédito 217:167–189

Ching A, Hayashi F (2010) Payment card rewards programs and consumer payment choice. J Bank Financ 34:1173–1787

Federal Reserve System (2016) Report on the Federal Reserve Payment Study, 2016. A Federal Reserve System Publication

Foley C (2011) Welfare payments and crime. Rev Econ Stat 93:97–112

Humphrey D, Willesson M, Lindblomand T, Goran B (2003) What does it cost to make a payment? Rev Netw Econ 2:159–174

Jonker N, Plooij M, Verburg J (2017) Did a public campaign influence debit card usage? Evidence from the Netherlands. J Financ Serv Res 52:89–121

Pew Charitable Trusts Research Brief (2016) Consumers need protection from excessive overdraft costs: an evidance-based case for regulation to limit the number and amount of fees. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/12/consumers_need_protection_from_excessive_overdraft_costs.pdf

Simon J, Smith K, West T (2010) Price incentives and consumer payment behaviour. J Bank Financ 34:1759–1772

Wright R, Tekin E, Topalli V, McClellan C, Dickinson T, Rosenfeld R (2017) Less cash, less crime: evidence from the electronic benefit transfer program. J Law Econ 60:361–383

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clerkin, N., Hanson, A. Debit Card Incentives and Consumer Behavior: Evidence Using Natural Experiment Methods. J Financ Serv Res 60, 135–155 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-020-00342-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-020-00342-9