Abstract

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of social skills training (SST) for juvenile offenders and for whom and under which conditions SSTs are the most effective.

Methods

Multilevel meta-analyses were conducted to examine the effectiveness of juvenile offender SST compared to no/placebo treatment and alternative treatment on offending, externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems.

Results

Beneficial effects were only found for offending and social skills compared to no/placebo treatment. Compared to alternative treatment, small effects on only reoffending were found. Moderator analyses yielded larger effects on offending, with larger post-treatment effects on social skills. Effects on externalizing behavior were only reported in the USA, and effects on social skills were larger when the outcomes were reported through self-report.

Conclusions

SST may be a too generic treatment approach to reduce juvenile delinquency, because dynamic risk factors for juvenile offending are only partially targeted in SST.

Similar content being viewed by others

Lacking social skills has been associated with problems on various life domains, and research over the past decades has repeatedly linked a lack of social skills with juvenile delinquency and reoffending (Dishion et al. 1984; Freedman et al. 1978; Gaffney and McFall 1981; Laak et al. 2003; Larson et al. 2007). As a risk factor for delinquency, social skills are often targeted in juvenile delinquency treatment to prevent reoffending. The assumption is that reducing the social skill deficits that led to the initial delinquent behavior will reduce subsequent delinquent behavior. One of the generic program types that is therefore often applied in juvenile offender treatment is social skills training (SST; Lipsey et al. 2010).

Research on the effectiveness of SST is elaborate, and SSTs have been included in many meta-analyses examining the effectiveness of offender treatment (Landenberger and Lipsey 2005; Lipsey et al. 2007; Lipsey et al. 2010; Lipsey 2009) as well as in meta-analyses on SST for emotionally and behaviorally disturbed juveniles (Ang and Hughes 2002; Cook et al. 2008; Maag 2006), with generally positive overall treatment effects. However, the comparison of SST within a broader denominator of offender treatment types on the one hand, or a broader target population on the other hand, leaves much unclear about the effectiveness of SST for juvenile offenders specifically. Moreover, the existing meta-analyses have had limited possibilities to determine for whom and under what circumstances SSTs are most effective for this specific target population (Kazdin 2007; Kazdin 2008; Kraemer et al. 2002). The present study aims to fill this gap by conducting a multi-level meta-analysis on the effectiveness of SST for juvenile delinquents on reoffending as well as other externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems.

Social skills enable juveniles to adequately respond to the social environment, to deal with stressful situations, and to prevent conflicts and punishment (Libet and Lewinsohn 1973; Matson and Wilkins 2007). Social skills generally include multiple cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes, such as problem-solving, perspective taking, moral reasoning, self-control, and positive behavioral skills (Ang and Hughes 2002; Spence 2003). Consequently, SSTs generally aim to modify social skills through addressing social interaction, pro-social behavior, and social cognitive skills (Gresham 2002; Gresham et al. 2004; Merrell and Gimpel 1998). Common themes in the training are as follows: emotion recognition and dealing with emotions, active listening, giving and receiving compliments, dealing with criticism and confrontations, and resisting peer pressure (Bijstra and Nienhuis 2003).

Although the variety in SSTs has resulted in a variety of treatment approaches, common treatment techniques are based on the following theories: social learning theory (Bandura 1977), operant learning theory (Skinner 1953), social information processing (Ladd and Mize 1983), structured learning theory (Goldstein et al. 1983), and multiple cognitive approaches (Cook et al. 2008; Kazdin 1992). Based on these theories, treatment techniques such as modeling, positive reinforcement, coaching, and role-playing are frequently used (Maag 2006).

Several meta-analyses have reported beneficial effects of SST, although few have specified treatment effects for adolescents and/or juvenile offenders specifically. For instance, SSTs have been included in a meta-analysis on treatment effectiveness for juvenile offenders aged 12 to 21, categorized as a skill building program among behavioral programs, cognitive-behavioral therapy, challenge programs, academic training, and job-related interventions (Lipsey 2009). These skill building programs were found to result in 12% less recidivism than a control group with a 50% recidivism rate, even when controlling for study design and demographic characteristics. Moreover, effects for these programs were larger with juveniles who were older, had a higher delinquency risk, and had a less aggressive history. Interventions were more effective with juveniles diverted to community treatment, and when the intervention implementation quality was relatively high. Although the differences between skill building program types were not significant, social skills training showed a reduction in recidivism of 13%, which was less than behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches, but more than challenge programs, academic training, and job-related interventions.

A mega-analysis synthesized the meta-analytic outcomes of SST meta-analyses on juveniles with emotional and behavioral problems for secondary school students (Cook et al. 2008). The included meta-analyses found overall small to large treatment effects for juveniles from 11 to 19 years old, compared to a majority of no or placebo treatment controls. Two of the included meta-analyses examined juveniles with (a risk for) antisocial behavior on broadly defined outcomes of antisocial behavior, social skills and social cognitive skills (mean d = .41; Lösel and Beelmann 2003), and social or behavioral adjustment (mean d = .66; Ang and Hughes 2002). Only one meta-analysis differentiated between juveniles with internalizing and those with externalizing behavior but found no difference in effect sizes between these groups (i.e., Beelmann et al. 1994, mean d = .45; Cook et al. 2008). The generally beneficial effects for adolescents with externalizing or antisocial behavior could indicate beneficial effects for juvenile offenders too. However, the overall effects were based on a broad variety of outcome measures, including, but not limited to, antisocial behavior and social(cognitive) skills.

While the abovementioned meta- and mega-analyses show effects that are promising for the effectiveness of juvenile offender SST, little is known about its specific effects and the conditions under which it is the most effective. Previous studies have made no or limited distinctions between the effects for offenders and juveniles with other (externalizing) behavior problems, between adolescents, children and adults, or between different outcome measures (e.g., offending). In the present meta-analytic study, we therefore only included studies examining juvenile offenders age 12 to 18 and conducted four separate meta-analyses to investigate the effects of SST on different outcomes: offending (which generally is the primary target in offender treatment), other externalizing problems (e.g., aggression), social skills, and internalizing problems. Given the promising effects in meta-analyses on juvenile offender treatment and SST, we expected positive treatment effects on all of these outcomes.

First, the majority of studies included in existing SST meta-analyses compared SST to a non-treatment and/or placebo control group. To examine whether SST is only effective compared to no treatment, or even superior compared to other treatment, we conducted separate analyses comparing SST to no treatment on the one hand, and alternative treatment on the other hand. By using a three-level meta-analysis design, with the possibility to include multiple effect sizes within studies, we were able to conduct moderator analyses to shed more light on whether, for which subgroups, and under which conditions SST is more effective than the alternative in treating juvenile offenders. In addition, this allowed for testing whether treatment effects on externalizing problems and social skills indeed moderated effects on reoffending, which has hardly been empirically supported yet (Andrews and Dowden 2007; Andrews and Bonta 2010b).

Second, in contrast with two of the previously mentioned meta-analyses on SST (i.e., Ang and Hughes 2002; Beelmann et al. 1994), we included published as well as non-published studies to reduce possible publication bias. One existing meta-analysis (Ang and Hughes 2002) only included studies published after 1975 to “restrict the studies to relatively contemporaneous times with regard to treatment practices, research standards, and cultural context” (pp. 166–167). To be able to obtain as many studies (and power) as possible, we did not restrict the publication period and included quasi-experimental studies in addition to randomized studies.

Third, the effects of gender, age, and ethnicity have been under-researched and have shown inconsistent results in previous meta-analysis on SSTs. We therefore investigated these sample characteristics as moderators. In line with outcomes of the available SST meta-analyses, we expected larger effects for older juveniles (Lipsey 2009). Because no differential treatment effects of SST for gender and ethnicity were found in previous meta-analyses, no moderating effects for these variables were expected in the present meta-analysis. Furthermore, previous SST reviews have indicated a decrease of SST treatment effects over time (Ang and Hughes 2002; Cook et al. 2008; Maag 2006), which was examined by including follow-up duration as an outcome characteristic moderator. Moreover, previous meta-analyses on (offender) treatment have found smaller effects for non-USA studies (Leijten et al. 2016; Van der Stouwe et al. 2014; Van Stam et al. 2014) and of higher study quality (Moher et al. 1998). Therefore, these characteristics were included as moderators.

Fourth, we included multiple treatment characteristics in moderator analyses. Given the larger SST effects for juveniles treated on diversion than for juveniles on probation and incarceration (Lipsey 2009), we expected larger treatment effects in non-residential treatment settings. Furthermore, because we included only offenders in the meta-analysis, we were not able to test the influence of group composition (deviant-only versus individual versus mixed). Previous research has shown smaller treatment effects in deviant-only group trainings, which has been attributed to negative peer influence (i.e., deviancy training) in those groups (Ang and Hughes 2002; Dishion et al. 1999). We could however include group size as a moderator, and we expected smaller treatment effects with larger treatment groups, hypothesizing that deviancy training would be more prevalent in larger group settings.

The following research questions were addressed in the current meta-analyses: (1) To what extent is SST effective in the prevention of recidivism? (2) To what extent is SST effective in decreasing externalizing problems, increasing social skills, and decreasing internalizing problems? (3) Which study, sample, treatment, and outcome (e.g., follow-up duration) characteristics have a moderating effect on heterogeneous outcomes?

Method

Selection of studies

All studies in English or Dutch before 2018 addressing the effectiveness of SST with juvenile offenders were included. In our search, we first set out to identify all studies on SSTs with, adolescents with externalizing problem behavior including offending. Within these studies, we then selected all studies including juvenile offenders for the present meta-analysis and then distinguished between studies comparing SST to a non-treatment/placebo or alternative treatment control group. Alternative treatment consisted of traditional probation services, regular residential youth care services, or alternative training and discussion groups.

Multiple electronic databases were searched in February and March 2018, the latest to identify relevant studies: Web of Knowledge (all databases), ScienceDirect, Narcis, Ovid (all databases), Wiley, Ebscohost (academic search premier, academic search alumni edition, ERIC, Open dissertations), Proquest (Ebook Central, ERIC, Periodicals Archive Online, Periodicals Index Online, Sociological Abstracts), Picarta, and Google Scholar. The search string consisted of multiple elements: “skills”, an intervention element (“training”, “intervention”, or “treatment”), an externalizing problems element (“delinquent”, “externalizing”, “aggression”, “deviant”, “conduct”, “emotionally disturbed”, or “problem behavior”), and a youth component (“juvenile”, “youth”, “adolescent”, or “child”), in both English and Dutch. Finally, we had to use terms to exclude irrelevant students to further narrow down our search results, such as NOT autism* or NOT attention-deficit. For example, in Google scholar, we searched using the command [skills AND (training OR intervention) AND (delinq* OR externalizing* OR aggression* OR deviant* OR conduct* OR emotional disturb* OR problem behav*) AND (juvenile OR youth OR adolescent OR child) NOT autism* NOT attention-deficit].

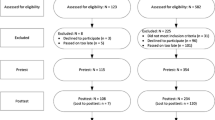

In addition, we searched the reference lists of related meta-analyses for relevant studies. Finally, we searched for specific SST (brand) names based on the results of the initial search, such as “social skills training,” “interpersonal problem-solving skills training,” “Reasoning and rehabilitation,” and “Aggression replacement/regulation training.” In case studies that could not be retrieved or did not report appropriate data to calculate an effect size, the authors were contacted to retrieve additional information. Only when these attempts proved to be unfruitful, the study was excluded. Figure 1 shows the flowchart for our search. We wrote a research protocol, which contains all moderators that were tested, and can be obtained from the first author.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the current meta-analyses, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) focus on SST, defined as treatment directed at improving specific social (interactional) skills, such as social problem-solving, and assertiveness, and/or decreasing social skill deficits, and described as such, (2) target juvenile offenders or report outcomes for offenders separately; (3) target juveniles age 12 to 18, or—in case age was not reported—7th to 12th grade; (4) employ a control group treatment design, where the control group contained juveniles from the same population, assigned to condition through random or quasi-experimental assignment; (5) report outcomes on offending, externalizing problems, social skills, and/or internalizing problems that enabled effect size calculation. Studies targeting learning disabled juveniles were excluded. The search yielded K = 28 studies, #ES = 580, reporting on N = 3124 juveniles, of whom n = 1691 received SST treatment.

Coding the studies

Each study was coded using a detailed coding system for recording outcomes and moderators following the guideline of Lipsey and Wilson (2001). The primary outcome was offending, defined as any delinquent or illegal post-treatment activity. For studies reporting on offending, social skills and externalizing problems outcomes reported within the same study were pooled and added as continuous moderators to include post-treatment effects on these outcomes as potential moderators. Secondary outcomes included externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems. Externalizing problems included antisocial attitudes (e.g., cognitive distortions), impulsivity, aggression, and other externalizing problem behavior (e.g., problem behavior in the classroom, incidents, non-specific externalizing behavior). The type of problems was an outcome characteristic included as a moderator. Social skills consisted of prosocial behavior and problem solving skills, and this distinction was also included as a potential moderator. For both externalizing problems and social skills, the informant (i.e., self-report versus others report) was also included as a potential moderator.

Moderators

Several study, sample, and treatment characteristics were coded as potential moderators. Whether the study was conducted outside the USA was dichotomously coded. Study quality was included as continuous moderator.

For study quality, we constructed a new study quality coding list, based on the Quality Assessment Tools for Quantitative Studies (QATQS, Thomas et al. 2004), the Quality Index (QI, Downs and Black 1998), and the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins et al. 2011). Although all these tools have their own strengths, they also have limitations that we tried to control for with this new list. First, in a previous study, we found that the QATQS did not differentiate enough in quality between studies (Van der Stouwe et al. 2014). With this list, points are only awarded for the highest study standards which most studies do not meet. The remaining points leave only little variation between normal practice less-than-perfect researches. Second, the QI is a very elaborate tool that leaves relatively much room for subjective interpretation, because the criteria based on which a study meets a certain quality characteristic are not clearly defined and there is no room for studies that only partially meet a criteria. Finally, the Cochrane Collaboration Tool is deliberately qualitative in nature, which makes it unsuitable for quantitative comparison in meta-analysis.

We constructed a list of 15 items assessing publication status (one item), selection bias, study design, blinding/dependence of authors, outcome measures, attrition and dropout, intervention, and sample description (all consisting of two items, Van der Stouwe 2016). We included the codings on every item for every study in Appendix Table 8. Every item had four possible answers with the answer representing the least study quality assigned 0 and the answer representing maximum study quality assigned 3 points. Studies could therefore score between 0 and 45 points for study quality, and in the present study, scores ranged from 9 to 37 points (mean (sd) = 20.04 (6.72), median = 21). We therefore believe that this checklist better serves the less-than-perfect research practice and the variation in study quality within those studies. The study quality list and its manual are available from the first author upon request.

Sample characteristics that were coded as potential moderators were mean sample age and proportion of males and ethnic minority juveniles in the sample. Unfortunately, some studies provided information about grade levels instead of mean age. To be able to include these studies in the age moderator analyses, we calculated average age based on the average age per grade level. Because there was little variance in these variables between studies, we coded all sample characteristics as dichotomous variables: under 16 years versus 16 years and older, 75% or less males versus over 75% males, and 50% or less ethnic minority versus over 50% ethnic minority.

In addition to the outcome-specific moderators (mentioned earlier), we coded the duration of follow-up. There was, however, too little variation to be able to include follow-up as a continuous moderator. We therefore dichotomized this variable into less than 6 months follow-up versus 6 months and longer follow-up.

Several treatment characteristics were coded as potential moderators. We coded whether treatment was residential (versus non-residential), and treatment group size was included as a continuous moderator. Studies were coded by the first, second, and third author. To determine interrater reliability, four studies were double-coded. Interrater agreement ranged from 95 to 100%.

Calculation and analysis

For each study outcome, we calculated an effect size of Cohen’s d, using formulas from Lipsey and Wilson (2001), and Wilson (2010), with a positive effect size indicating better results for the SST group. To control for pre-treatment differences on the outcome measure, we calculated effect sizes for both pre-treatment and post-treatment and then subtracted the pre-treatment effect from the post-treatment effect whenever possible. When outcome effects were reported to be non-significant without reporting statistics to be able to calculate an effect size, we conservatively estimated the effect size to be 0 (Lipsey and Wilson 2001).

Several steps were taken to prepare the data for data-analysis. Effect sizes and continuous moderators were examined for outliers using their Z-distribution. Extreme values (> 3.29 SD from the mean; Tabachnick and Fidell 2013) were winsorized by recoding them into the nearest non-outlier. For offending and internalizing problem outcomes, no outliers were recoded. For externalizing behavior outcomes, one study with a no/placebo treatment comparison group contained two outlying effect sizes d = − 8.56 and d = − 4.13; Garrido and Sanchis 1991), and one of the studies with an alternative treatment comparison group yielded an outlying group size (group size = 30; Tellier 1998). Finally, for social skills outcomes, one study with a no treatment/placebo control group had two effect sizes that needed to be winsorized (d = 2.26, and d = − 1.37; Feindler 1979). For the studies with alternative treatment comparisons, one study had a larger treatment group (20, Leeman et al. 1993), and one effect size needed to be winsorized (d = − 2.38, Scholte and Van der Ploeg 2003, 2006).

To determine sensitivity for our recoding, we conducted the analyses with and without recoding of outliers for all outcomes. There were no substantial differences between the analyses with or without recoding of these outliers (externalizing behavior: no/placebo treatment d = .03, 95% CI = − .76–.82, t = .07, p = .94; alternative treatment group size β1 = .01, t1 = .75, p = .750; social skills: no/placebo treatment d = .54, 95% CI = .36–.72, t = 6.05, p < .001; alternative treatment d = .09, 95% CI = − .16–.34, t = .73, p = .47, group size β1 = .01, t1 = .42, p = .676).

Continuous moderators were centered around their mean, categorical moderators were dummy-coded, and standard errors and sampling variance were calculated using formulas by Lipsey and Wilson (2001).

In traditional meta-analysis, effect sizes and effect size characteristics are pooled within studies, because only one effect size per study can be included in the analysis, which generally results in a loss of information and power. To retain maximum information and power, and to be able to conduct comprehensive moderator analyses, we conducted a multi-level meta-analysis following the approach suggested by Van den Noortgate and Onghena (2003). The meta-analysis was conducted in R (version 3.4.1) with the metafor-package, using a 3-level random effects model to account for sampling variance (level 1), variance between effect sizes within studies (level 2), and variance between studies (level 3), which account for the interdependency of effect sizes that exists when multiple effect sizes per study are included (Assink and Wibbelink 2016; Houben et al. 2015; Van den Bussche et al. 2009; Viechtbauer 2010). To examine heterogeneity of the effect size distribution, we tested for significant variance at levels 2 and 3 using likelihood ratio tests comparing the full model to models excluding the variance parameters of levels 2 and 3, respectively (Assink and Wibbelink 2016). If there is significant variance on the two levels, the effect size distribution is considered heterogeneous, and the overall mean cannot be treated as an estimate of a common effect size. If this was the case, the model was extended by including study, sample, outcome, and treatment characteristics to examine whether those had a moderating effect on SST treatment effects. We only conducted these moderator analyses for studies comparing SST to alternative treatment.

File drawer analysis

A common threat to the generalizability of meta-analytic outcomes is publication or file drawer bias (Rosenthal 1995). Because studies with non-significant or unfavorable outcomes are published less often, studies included in meta-analysis may not be an adequate representation of all existing studies and may therefore provide an optimistic image of actual treatment effects. We tried to control for this type of bias by including all studies we could find and not just studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In addition, we tested for funnel plot asymmetry using Egger’s method (Egger et al. 1997). If no publication bias is present, the effect sizes should result in a symmetrical funnel plot (plotted against their precision) and result in a non-significant intercept in Egger’s test. Furthermore, we conducted a trim and fill procedure (Duval and Tweedie 2000a; Duval and Tweedie 2000b) to examine the influence of (correcting for) funnel plot asymmetry using MIX 2.0 (Bax 2011). The trim and fill procedure estimates missing effect sizes based on the existing effect size distribution. If the trim and fill procedure led to the estimation of missing effect sizes, we imputed the effect sizes within studies and reran the overall effect size analyses including these estimates.

Results

The current meta-analyses consist of K = 28 studies, #ES = 580, reporting on N = 3124 juveniles, of whom n = 1691 received SST treatment. Of these studies, K = 17 studies and #ES = 306 reported about a comparison with a no/placebo treatment control group, while K = 16 studies and #ES = 274 compared SST to alternative treatment. Because not all studies reported on all examined outcome measures, the number of studies, effect sizes, and juveniles differs between outcome measures. The coded study, sample, treatment, and outcome characteristics are included in Appendix Tables 5, 6, and 7.

Overall effects

Table 1 summarizes the overall effects for offending, externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems.

Offending

Offending outcomes comparing SST with a no treatment/placebo control group were reported on N = 385 juveniles including n = 174 juveniles who received SST. A significant overall effect was found (d = .28, 95% CI = .12–.43): after SST, juveniles showed less offending than juveniles who did not receive treatment or received a placebo treatment. Egger’s method did not show significant funnel plot asymmetry (B = − .19, t = − 0.17, p = .87), and a trim and fill procedure did not indicate any missing effect sizes (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, b). This outcome may therefore be robust to publication and file drawer bias.

A comparison of SST with alternative treatment for offending outcomes was reported for N = 2371 juveniles of whom n = 1314 received SST treatment. Again, a significant, yet smaller treatment effect, was found (d = .08, 95% CI = .00–.16). Compared to alternative treatment, juveniles showed slightly less offending after SST. However, Egger’s method indicated funnel plot asymmetry (B = .65, t = 2.25, p = .027). After a trim and fill procedure to correct for this asymmetry (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, 2000b), the overall effect size was no longer significant (d = − .01, 95% CI = − .18–.15).

Moreover, there was significant variance between effect sizes within studies (σ2level2 = .01, χ2 (1) = 4.53, p = .03), which explained 24% of the total variance, but no significant variance between studies (σ2level3 = .01, χ2 (1) = 3.62, p = .06), which explained 15% of the total variance.

Externalizing problems

For externalizing problems, outcomes comparing SST to a no treatment/placebo control group were reported on N = 609 juveniles, with n = 322 juveniles receiving SST. These studies showed a non-significant treatment effect (d = .25, 95% CI = − .11–.67). Although Egger’s method did not show significant funnel plot asymmetry (B = .76, t = 1.41, p = .16), a trim and fill procedure showed that studies with outcomes unfavorable to SST were underreported. After this procedure, a smaller, still non-significant effect was found (d = .10, 95% CI = − .34–.54).

The comparison of SST treatment effects with alternative treatment effects on externalizing problems could be examined for N = 701 juveniles, including n = 369 juveniles receiving SST. No significant overall effect was found (d = .11, 95% CI = − .13–.34) for the comparison with alternative treatment. Although Egger’s method did not show significant funnel plot asymmetry (B = − .50, t = − 1.14, p = .26), a trim and fill procedure resulted in the addition of few effect sizes (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, b), yielding still a non-significant overall effect (d = .34, 95% CI = − .04–.72).

There was no significant variance between effect sizes within studies (σ2level2 = .00, χ2 (1) = 0, p = 1), which explained 0% of the total variance, but there was significant variance between studies (σ2level3 = .16, χ2 (1) = 27.16, p = .000), which explained 74% of the total variance.

Social skills

For N = 513 juveniles and n = 271 of them receiving SST, a comparison could be made for social skills after SST compared to no treatment/placebo treatment. When SST was compared to a no treatment control group, a significant treatment effect was found (d = .54, 95% CI = .37–.72). After SST treatment, juveniles showed more social skills than juveniles who did not receive any treatment. The overall effect was even larger (d = .72, 95% CI = .49–.95) after a trim and fill procedure had been conducted (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, b) to correct for funnel plot asymmetry (B = − .82, t = − 2.12, p = .036).

The effects of SST compared to alternative treatment could be examined for N = 663 juveniles including n = 348 juveniles receiving SST. The overall effect on social skills was non-significant (d = .11, 95% CI = − .13–.34). Moreover, Egger’s method indicated funnel plot asymmetry (B = 1.14, t = 4.27, p = .000). After a trim and fill procedure to correct for this asymmetry (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, b), a smaller and still non-significant overall effect was found (d = − .28, 95% CI = − .62–.06).

There was significant variance between effect sizes within studies (σ2level2 = .08, χ2 (1) = 17.25, p = .000), which explained 28% of the total variance, as well as significant variance between studies (σ2level3 = .11, χ2 (1) = 23.19, p = .000), which explained 37% of the total variance.

Internalizing problems

Outcomes for internalizing problems were reported on N = 135 juveniles, including n = 79 who received SST and n = 56 who received no/placebo treatment. Compared to the non-treatment control groups, a non-significant effect was found (d = − .45, 95% CI = − 1.12–.23). Egger’s method indicated funnel plot asymmetry (B = − 4.42, t = − 3.05, p = .012). A trim and fill procedure (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, 2000b) yielded a smaller overall effect, which still proved to be non-significant (d = − .09, 95% CI = − .97–.79).

A total of N = 165 juveniles reported on internalizing problems after receiving SST or alternative treatment, with n = 105 of them receiving SST. For them, no significant overall effect was found (d = .24, 95% CI = − .67–1.15). Furthermore, there was no significant funnel plot asymmetry (B = 2.27, t = 1.03, p = .33), indicating that the overall effect size for internalizing problems is robust to publication and file drawer bias.

There was no significant variance between effect sizes within studies (σ2level2 = .00, χ2 (1) = 0, p = 1.000), but there was significant variance between studies (σ2level3 = .62, χ2 (1) = 10.64, p = .001), which explained 84% of the total variance. Because internalizing problems were only reported for K = 4 studies and #ES = 12 effect sizes, moderator analyses could not be performed.

Moderator analysis

Offending

Table 2 presents the results of the moderator analyses for offending. Only two significant moderating effects were found. The treatment effect on social skills had a significant moderating effect on reoffending. For the K = 5 studies that reported on both offending and social skills outcomes, we found that studies with larger average (post-treatment) effects on social skills showed larger effects on reoffending. No moderating effects were found for study (country, quality), sample (age, gender, ethnicity), and outcome (follow-up duration) characteristics or the remaining treatment characteristics (setting, group size) and other outcome measures (externalizing problems).

Externalizing problems

Moderator analyses for externalizing problems were conducted for the same moderators as for offending. In addition, the moderating effects of the informant (self versus others) and the type of externalizing behavior (impulsivity, antisocial attitudes, aggression and other externalizing behavior) were examined (see Table 3). Only one moderating effect was found for country where the research was conducted. SST showed larger treatment effects for studies conducted in the USA than outside the USA, although neither location showed significant treatment effects. No moderating effects were found for study quality or sample (age, gender, ethnicity), treatment (setting, group size), and outcome-specific characteristics.

Social skills

Table 4 shows that moderator analyses for social skills were conducted for the same moderators as for offending. In addition, the moderating effects of the informant (self versus others) and type of social skills (prosocial behavior versus problem-solving skills) were examined. Only one moderator was found to have a moderating effect on social skills outcomes. Effects on social skills showed to be larger when they were measured through self-report than other-report. However, the effects were non-significant for both reporting sources. No moderating effects were found for outcome type, or other study (country, quality), sample (age, gender, ethnicity), and treatment (setting, group size) characteristics.

Discussion

A series of multi-level meta-analyses were conducted to examine the effectiveness of SST for juvenile offenders on offending, externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems. In contrast to previous quantitative reviews, we distinguished between effects in no/placebo treatment and alternative treatment comparisons. The effects of SST compared to a no/placebo treatment control group are line with those found in previous meta-analyses (see, e.g., Cook et al. 2008; Lipsey 2009): significant treatment effects were found for offending (d = .25, 95% CI = .12–.43) and social skills (d = .54, 95% CI = .37–.72), but no treatment effects were found for externalizing and internalizing problems. Moreover, these effects remained significant after correction for publication and file drawer bias by means of trim and fill analyses.

We only found a small significant treatment effect for SST in comparison with alternative treatment for offending outcomes (d = .08, 95% CI = .00–.16). A trim and fill procedure for offending resulted in a non-significant overall effect, indicating that studies with negative treatment effects are less likely to be reported and that the available research base may overestimate the actual effects of SST on juvenile (re)offending. For outcomes on externalizing problems, social skills, and externalizing problems, we found no significant overall treatment effects, either before or after trim and fill analyses. These overall treatment effects show that although SST is better than doing nothing in the prevention of juvenile (re)offending, its superiority over treatment alternatives is questionable. It seems that SST is successful in improving social skills, but that it is not superior to alternative treatment in doing so. Arguably, other (cheaper) treatment alternatives would suffice just as much.

Moderator analyses were only conducted for the comparison with alternative treatment. We found that studies with larger (post-treatment) effects on social skills yielded larger effects on reoffending. Additionally, although we found no significant differences between subgroups on these outcomes, the moderator analyses showed significant positive treatment effects for studies with less than 75% males, in residential settings, and for outcomes at a follow-up of 6 months and longer. Interestingly, the latter could indicate that SST effects generally increase over time, even though previous meta-analyses have reported the opposite (Ang and Hughes 2002; Cook et al. 2008; Maag 2006).

The moderating influence of (post-)treatment effects on social skills supports the assumption that improving social skills deficits—that arguably have resulted in the delinquent behavior—would lead to a reduction of delinquent behavior. This is, however, difficult to reconcile with the fact that we did not find any significant overall effects on social skills outcomes. This may be explained by the other moderator analyses that found larger effects for studies with more girls and in residential settings. It can be argued that lack of significant overall effects on social skills may partly be explained by great differences in the quality or application of SST among different populations of juvenile offenders and treatment settings, which cannot be fully captured in moderator analyses, yielding highly inconsistent results at the individual level and a multitude of subgroups. The present outcomes would then indicate that only in those (rare) cases that SST is superior to alternative treatment in improving social skills; it may, in turn, improve reoffending in the long term.

For externalizing problems, moderating effects were only found for the country where the study was conducted. Only in the USA, and not in other countries, treatment effects were significant (d = . 28, 95% CI = − .01–.56). This is not surprising, given the fact that previous meta-analyses on (offender) treatment have found smaller effects for non-USA studies as well (Leijten et al. 2016; Van der Stouwe et al. 2014; Van Stam et al. 2014). It may be necessary to make more culture-specific adaptations to the contents of SST to be applied outside the USA.

For SST effects on social skills, significant moderating effects were only found for informant. Treatment effects were—although non-significant—larger when the outcomes were reported through self-report (d = .23, 95% CI = − .02–.54) and not by parents, teacher, or SST trainers. This is particularly interesting, given the fact that existing literature showed that juvenile delinquents generally under, and not overreport their behavioral problems (Breuk et al. 2007; Vreugdenhil et al. 2006). However, our current outcomes may also be explained by low agreement between informants, which is not uncommon in research on juvenile offenders (De Los Reyes et al. 2015; Forehand et al. 1991.

The fact that we did not find any significant SST treatment effects for juvenile offenders compared to alternative treatment could indicate that targeting social skills as a main risk factor for delinquency might be outdated. First, it is almost never included as a separate risk factor based on contemporary risk assessment research (see e.g., Assink et al. 2015; or Jolliffe et al. 2017). Second, while there is little empirical evidence supporting the relative importance of different risk factors (Singh and Fazel 2010), social skills deficits are not included as one of the Central Eight most important risk factors for reoffending (Andrews and Bonta 2010a). At best, some overlap could be considered with the risk factor antisocial cognition, and most SSTs may indirectly focus on the Moderate Four risk factors (i.e., family/marital circumstances, school/work, leisure/recreation, substance abuse). Third, the dynamic predictive validity of social skills deficits is questionable, given the fact that a recent study found that only changes in antisocial attitudes/behaviors and aggression specifically, and not changes in social skills, were predictive of a recidivism reduction for juvenile offenders after residential placement, although all three constructs (regardless of change) were predictive of recidivism (Baglivio et al. 2017). Juvenile offender treatment should therefore target risk factors such as antisocial attitudes and aggression more specifically than SST does.

Moreover, the fact that SST shows similar effects as any alternative treatment might support the dodo-bird hypothesis, that is, the assumption that all treatments will be equally effective based on their common therapeutic characteristics (Wampold et al. 1997). This should not be too surprising given the fact that multiple social skills should be addressed and modeled in a therapeutic relation alone. However, recent reviews have shown that—in contrast to the dodo-bird hypothesis—most treatments still show better effects on their primary treatment target than alternative treatment at posttest, but not at follow-up (Marcus et al. 2014; Weisz et al. 2017). Given the lack of treatment effects on social skills and offending (i.e., the primary outcomes) when compared to alternative treatment, SST would then fair worse than other treatments at post treatment, at least in improving social skills and reducing reoffending for juvenile offenders.

This study needs to be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, as is the case with every meta-analytic study, we had to depend on the quality and elaborateness of reporting in the included studies, which may result in unreliability of the information. We therefore established interrater agreement by double-coding 4 of the 28 included studies that were included in our meta-analysis. Although interrater agreement was high, scoring a subset of studies to establish interrater reliability—which is a common practice in scientific research—does not ensure generalizability to all studies. However, any uncertainty in the coding of the remaining articles was resolved by means of consultation of one of the other senior researchers involved in the current meta-analysis.

The lack of (explicitly) reporting about characteristics such as age, ethnicity, follow-up duration, and treatment (techniques) limited the possibilities for moderator analyses. A small number of studies reported outcomes about internalizing problems, and moderator analyses could therefore not be conducted for this outcome. Only 5 studies reported on externalizing problems or social skills in addition to offending outcomes, which limited the statistical power of moderator analyses including these outcomes. Moreover, several studies were excluded because they could not be obtained (K = 21), mostly because they were too old to be available (digitally) or did not report data suitable to calculate an effect size (K = 8).

Second, although we tried to limit the number of moderators, we have conducted about ten moderator tests per outcome, which has increased the chances of finding a false positive, i.e., finding a significant moderator that in fact is not significant. Third, the moderating effects we examined for sample characteristics only included study-level demographics that merely provided a general indication of the moderating effects of participant level demographics. To determine the effects of SST for specific age, gender, and ethnic groups, these effects should be further examined within studies for these demographic groups separately. Finally, although our study quality checklist showed promising properties in the present study, it should serve merely as a global indication of study quality. Moreover, its psychometric characteristics are currently unknown, although it was based on already well-validated study quality checklists, which still did not sufficiently meet the purpose of our meta-analysis. Therefore, future (comparison) research is warranted to determine the theoretical and practical value of our newly devised study quality instrument.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine SST effects for adolescent juvenile offenders. In contrast to existing meta-analyses, we made a distinction between a no/placebo treatment comparison and a comparison to alternative treatment. Next, we conducted separate multi-level meta-analyses for four separate outcomes: offending, externalizing problems, social skills, and internalizing problems. The beneficial treatment effects that have been reported in previous meta-analytic studies (see e.g., Beelmann et al. 1994; Ang and Hughes 2002; Lösel and Beelmann 2003; Cook et al. 2008) seem to be mostly based on a comparison with a no/placebo treatment control group: SST is better than doing nothing in the prevention of juvenile (re)offending, and improving social skills. However, SSTs may be—at best—only slightly superior to alternative treatment in reducing reoffending, potentially only in those few cases where sufficient treatment effects on social skills were obtained. Consequently, SST may be a too generic treatment approach to be effective in reducing juvenile delinquency because dynamic risk factors for juvenile offending are only partially targeted in SST.

References

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010a). The psychology of criminal conduct (5th ed.). New Providence, NJ: Matthew Bender & Company, Inc..

Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010b). Rehabilitating criminal justice policy and practice. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16, 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018362.

Andrews, D. A., & Dowden, C. (2007). The risk–need–responsivity model of assessment and human service in prevention and corrections: Crime-prevention jurisprudence. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice/La Revue Canadienne De Criminologie Et De Justice Pénale, 49, 439–464. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.49.4.439.

Ang, R. P. (2003). Social problem-solving skills training: does it really work? Child Care in Practice, 9, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270302169.

Ang, R. P., & Hughes, J. N. (2002). Differential benefits of skills training with antisocial youth based on group composition: a meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Review, 31, 164–185.

Assink, M., van der Put, C. E., Hoeve, M., de Vries, S. L. A., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Oort, F. J. (2015). Risk factors for persistent delinquent behavior among juveniles: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.002.

Assink, M., & Wibbelink, C. J. M. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: a step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12, 154-174. doi:https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.12.3.p154.

Baglivio, M. T., Wolff, K. T., Jackowski, K., & Greenwald, M. A. (2017). A multilevel examination of risk/need change scores, community context, and successful reentry of committed juvenile offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 15, 38–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204015596052.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Barker, N. C. (1998). Can specialized after-school programs impact delinquent behavior among African American youth? Proceedings of the Annual Research Conference, A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base, 10, 345–350.

Barnoski, R. P., & Aos, S. (2004). Outcome evaluation of Washington state’s research-based programs for juvenile offenders. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy Retrieved from http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/rptfiles/04-01-1201.pdf.

Bax, L. (2011). Professional software for meta-analysis in excel (2014th ed.) BiostatXL.

Beelmann, A., Pfingsten, U., & Lösel, F. (1994). Effects of training social competence in children: a meta-analysis of recent evaluation studies. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23, 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2303_4.

Bijstra, J., & Nienhuis, B. (2003). Sociale-vaardigheidstrainingen meten we of meten we niet? [Social skills training do we or do we not measure?] Psycholoog - Amsterdam, 38, 174–178.

Bottcher, J. (1985). The athena program: an evaluation of a girl’s treatment program at the Fresno county probation department’s juvenile hall. Fresno: California Department of the Youth Authority.

Bowman, P. C., & Auerbach, S. M. (1982). Impulsive youthful offenders: a multimodal cognitive behavioral treatment program. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 9, 432–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854882009004003.

Breuk, R. E., Clauser, C. A. C., Stams, G. J. J. M., Slot, N. W., & Doreleijers, T. A. H. (2007). The validity of questionnaire self-report of psychopathology and parent–child relationship quality in juvenile delinquents with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 761–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.10.003.

Bunford, N. (2016). Interpersonal skills group - corrections modified for detained juvenile offenders with externalizing disorders: a controlled pilot clinical trial. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation,). Ohio University,

Cook, C. R., Gresham, F. M., Kern, L., Barreras, R. B., Thornton, S., & Crews, S. D. (2008). Social skills training for secondary students with emotional and/or behavioral disorders: a review and analysis of the meta-analytic literature. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426608314541.

De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A., Burgers, D. E., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 858–900. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038498.

Dishion, T. J., Loeber, R., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Patterson, G. R. (1984). Skill deficits and male adolescent delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913460.

Dishion, T. J., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When interventions harm: peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 755–764. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755.

Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52, 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.52.6.377.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000a). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669529.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000b). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56, 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Elrod, H. P., & Minor, K. I. (1992). Second wave evaluation of a multi-faceted intervention for juvenile court probationers. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 36, 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X9203600308.

Erickson, J. A. (2013). The efficacy of aggression replacement training with female juvenile offenders in a residential commitment program. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). University of South Florida, Tampa. (Scholar Commons: 4479).

Feindler, E. L. (1979). Cognitive and behavioral approaches to anger control training in explosive adolescents. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). West Virginia University, Morgantown. (UMI: 8012919).

Forehand, R., Frame, C. L., Wierson, M., Armistead, L., & Kempton, T. (1991). Assessment of incarcerated juvenile delinquents: agreement across raters and approaches to psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 13, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00960736.

Freedman, B. J., Rosenthal, L., Donahoe Jr., C. P., Schlundt, D. G., & McFall, R. M. (1978). A social-behavioral analysis of skill deficits in delinquent and nondelinquent adolescent boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 1448–1462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.46.6.1448.

Gaffney, L. R., & McFall, R. M. (1981). A comparison of social skills in delinquent and nondelinquent adolescent girls using a behavioral role-playing inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.49.6.959.

Garrido, V., & Sanchis, J. R. (1991). The cognitive model in the treatment of Spanish offenders: theory and practice. Journal of Correctional Education, 42, 111–118.

Goldstein, A. P., Sprafkin, R. P., Gershaw, N. J., & Klein, P. (1983). Structured learning: a psychoeducational approach for teaching social competencies. Behavioral Disorders, 8, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874298300800307.

Green-Burns, W. B. (1979). Anger control as a method of treatment for juvenile delinquency. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. (UMI: 8015574).

Gresham, F. M. (2002). Best practices in social skills training. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology IV (pp. 1029–1040). Washington, DC: National Association of School Psychologists.

Gresham, F. M., Cook, C. R., Crews, S. D., & Kern, L. (2004). Social skills training for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders: validity considerations and future directions. Behavioral Disorders, 30, 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290403000101.

Guerra, N. G., & Slaby, R. G. (1990). Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders: 2. Intervention. Developmental Psychology, 26, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.26.2.269.

Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtze, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj, 343, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Houben, M., Van den Noortgate, W., & Kuppens, P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 901–930. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038822.

Jeong, S., Fenoff, R., & Martin, J. H. (2017). Evaluating the effectiveness of an evidence-based cognitive restructuring approach: 1-year results from project ASPECT. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 10, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct_2016_09_16.

Jolliffe, D., Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., Loeber, R., & Hill, K. G. (2017). Systematic review of early risk factors for life-course-persistent, adolescence-limited, and late-onset offenders in prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.009.

Kaya, F., & Buzlu, S. (2016). Effects of aggression replacement training on problem solving, anger and aggressive behaviour among adolescents with criminal attempts in Turkey: a quasi-experimental study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30, 729–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2016.07.001.

Kazdin, A. E. (1992). Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 733–747.

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432.

Kazdin, A. E. (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63, 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146.

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 877–883. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877.

Ladd, G. W., & Mize, J. (1983). A cognitive–social learning model of social-skill training. Psychological Review, 90, 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.90.2.127.

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. (2005). The positive effects of cognitive–behavioral programs for offenders: a meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 451–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-005-3541-7.

Larson, J. J., Whitton, S. W., Hauser, S. T., & Allen, J. P. (2007). Being close and being social: peer ratings of distinct aspects of young adult social competence. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89, 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701468501.

Latzman, T. L. (2008). An evaluation of project peer: a juvenile delinquency treatment program. (Unpublished Doctoral Project). Pace University, New York. (UMI: 3322473).

Leeman, L. W., Gibbs, J. C., & Fuller, D. (1993). Evaluation of a multicomponent group treatment program for juvenile delinquents. Aggressive Behavior, 19, 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337.

Leijten, P., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Knerr, W., & Gardner, F. (2016). Transported versus homegrown parenting interventions for reducing disruptive child behavior: a multilevel meta-regression study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55, 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.03.

Libet, J. M., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1973). Concept of social skill with special reference to the behavior of depressed persons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40, 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034530.

Lipsey, M. W., Howell, J. C., Kelly, M. R., Chapman, G., & Carver, D. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of juvenile justice programs: a new perspective on evidence-based practice. Washington: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform.

Lipsey, M. W., Landenberger, N. A., & Wilson, S. J. (2007). Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2007.6.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). In Bickman L., Rog D. J. (Eds.), Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Lipsey, M. W. (2009). The primary factors that characterize effective interventions with juvenile offenders: a meta-analytic overview. Victims & Offenders, 4, 124–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564880802612573.

Long, S. J., & Sherer, M. (1985). Social skills training with juvenile offenders. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 6, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v06n04_01.

Lösel, F., & Beelmann, A. (2003). Effects of child skills training in preventing antisocial behavior: a systematic review of randomized evaluations. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587, 84–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716202250793.

Maag, J. W. (2006). Social skills training for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: a review of reviews. Behavioral Disorders, 32, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290603200104.

Marcus, D. K., O’Connell, D., Norris, A. L., & Sawaqdeh, A. (2014). Is the dodo bird endangered in the 21st century? A meta-analysis of treatment comparison studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.001.

Matson, J. L., & Wilkins, J. (2007). A critical review of assessment targets and methods for social skills excesses and deficits for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2006.07.003.

Merrell, K. W., & Gimpel, G. A. (1998). Social skills of children and adolescents: conceptualization, assessment, treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mitchell, J., & Palmer, E. J. (2004). Evaluating the “reasoning and rehabilitation” program for young offenders. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 39, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v39n04_03.

Moher, D., Pham, B., Jones, A., Cook, D. J., Jadad, A. R., Moher, M., et al. (1998). Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? The Lancet, 352, 609–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X.

Ollendick, T. H., & Hersen, M. (1979). Social skills training for juvenile delinquents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 17, 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(79)90098-6.

Pullen, S. K. (1996). Evaluation of the reasoning and rehabilitation cognitive skills development program as implemented in juvenile ISP in Colorado Office of Research and Statistics, Division of Criminal Justice, Colorado Department of Public Safety.

Rosenthal, R. (1995). Writing meta-analytic reviews. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.2.183.

Sarason, I. G., & Ganzer, V. J. (1973). Modeling and group discussion in the rehabilitation of juvenile delinquents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 20, 442–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035389.

Schlichter, K. J., & Horan, J. J. (1981). Effects of stress inoculation on the anger and aggression management skills of institutionalized juvenile delinquents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173687.

Scholte, E. M., & Van der Ploeg, J. D. (2003). Effectiveness of residential treatment methods for youngsters with severe behavioural problems: findings from a one year follow-up study. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare, 4, 185–197.

Scholte, E. M., & Van der Ploeg, J. D. (2006). Residential treatment of adolescents with sever behavioural problems. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.05.010.

Shivrattan, J. L. (1988). Social interactional training and incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 30, 145–163.

Singh, J. P., & Fazel, S. (2010). Forensic risk assessment: a metareview. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 965–988. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810374274.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York, NJ: MacMillan.

Spence, S. H. (2003). Social skills training with children and young people: theory, evidence and practice. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 8, 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-3588.00051.

Steele, P. D. (1991). Youth corrections mediation program: final report of evaluation activities. Albuquerque: Youth Resource and Analysis Center, University of Mexico/New Mexico Center for Dispute Resolution.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston: Ally and Bacon.

Tellier, J. E. (1998). Anger and depression among incarcerated juvenile delinquents: a pilot intervention. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Wright Institute Graduate School of Psychology, Berkeley. (UMI: 9912972).

Ter Laak, J., De Goede, M., Aleva, L., Brugman, G., Van Leuven, M., & Hussmann, J. (2003). Incarcerated adolescent girls: personality, social competence, and delinquency. Adolescence, 38, 251–265.

Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x.

Tofte-Tipps, S. J. (1980). Group social skills training of adolescents with school adjustment problems. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). North Texas State University, Denton. (UMI: 8029019).

Van den Bussche, E., Van den Noortgate, W., & Reynvoet, B. (2009). Mechanisms of masked priming: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 452–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015329.

Van den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2003). Multilevel meta-analysis: a comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 765–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403251027.

Van der Stouwe, T. (2016). Manual for using the study quality checklist. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Van der Stouwe, T., Asscher, J. J., Stams, G. J. J. M., Deković, M., & Van der Laan, P. H. (2014). The effectiveness of multisystemic therapy (MST): a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.006.

Van der Stouwe, T., Asscher, J. J., Stams, G. J. J. M., Hoeve, M., & Van der Laan, P. H. (2015). Effectstudie Tools4U: Effecten op cognitieve en sociale vaardigheden. Onderzoek effecten van leerstraf Tools4U op cognitieve en sociale vaardigheden [Effectiveness study Tools4U: effects on cognitive and social skills. Study effects of penal sanction Tools4U on cognitive and social skills.]. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, Forensische Orthopedagogiek.

Van Stam, M. A., Van der Schuur, W. A., Tserkezis, S., Van Vugt, E. S., Asscher, J. J., Gibbs, J. C., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2014). The effectiveness of EQUIP on sociomoral development and recidivism reduction: a meta-analytic study. Children and Youth Services Review, 38, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.002.

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03.

Vreugdenhil, C., Van den Brink, W., Ferdinand, R., & Wouters, L. (2006). The ability of YSR scales to predict DSM/DISC-C psychiatric disorders among incarcerated male adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0497-8.

Wampold, B. E., Mondin, G. W., Moody, M., Stich, F., Benson, K., & Ahn, H. (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: empirically, “all must have prizes”. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.203.

Weisz, J. R., Kuppens, S., Ng, M. Y., Eckshtain, D., Ugueto, A. M., Vaughn-Coaxum, R., et al. (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. American Psychologist, 72, 79–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040360.

Wilson, D. B. (2010). Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator. Retrieved from http://gemini.gmu.edu/cebcp/EffectSizeCalculator/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Stouwe, T., Gubbels, J., Castenmiller, Y.L. et al. The effectiveness of social skills training (SST) for juvenile delinquents: a meta-analytical review. J Exp Criminol 17, 369–396 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09419-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09419-w