Abstract

The mechanical behaviour of natural, unfilled rock joints is influenced by the interaction between surface roughness and matedness of the contact surfaces. In the field, natural rock joints normally exhibit a mismatch between the contact surfaces, mainly due to different geological processes such as weathering or deformations. Various attempts have been made to estimate how matedness of rock joints influences their peak shear strength. However, the proposed methodologies imply certain difficulties since they are intended to estimate the matedness of rock joints based mainly on visual inspection, and by relating an initial shear displacement to the length of the analysed sample or by relating the opening of saw-tooth and two-dimensional joint profiles with the degree of interlocking. Therefore, a tested peak shear strength criterion for natural, unfilled rock joints that realistically accounts for the influence of matedness on their peak shear strength is still lacking. This paper presents a methodology where objective measurements of the average aperture of natural, unfilled rock joints are used to estimate their matedness as a step in the prediction of the peak shear strength. This measured average aperture is based on high-resolution optical scanning of the surface roughness. The proposed relationship between measured average aperture and matedness of natural rock joints has been included in a further developed peak shear strength criterion. The verification against ten natural rock joint samples of coarse-grained granite showed that the revised criterion can predict the peak shear strength considering rock joint matedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The assessment of rock joint shear strength is one of the most common problems that engineers face in the design and construction of engineering structures on or in rock masses (e.g., stability analysis of dams, block and arching stability in tunnels, slope stability analysis). It is widely recognised that the peak shear strength of rock joints is affected by a number of different parameters, for example the normal stress acting on the joint surface, the degree of weathering, mineral coatings and infillings, surface roughness, the matedness of the rock joint and the scale. For this reason, the peak shear strength of rock joints has been under study in recent decades.

Patton (1966) was one of the first researchers to describe the shear behaviour of rock joints with regular and saw-tooth asperities. Based on the same idealized rock joint model, Ladanyi and Archambault (1969) approached the problem of shear strength of rock joints by identifying those areas where sliding on and shearing of the asperities are most likely to occur depending on the degree of interlocking. Barton (1973) and Barton and Choubey (1977) proposed an empirical shear strength criterion that included the contribution from joint roughness and joint surface compressive strength of a rock joint. Surface roughness is expressed in this criterion by the well-known joint roughness coefficient (JRC). This parameter is normally estimated subjectively in the field through comparison with predefined roughness profiles, or preferably by back-calculation based on a single tilt test of the analysed rock joint (Barton and Choubey 1977). Efforts have been made to gain more insight into the mechanical behaviour of rock joints based on a statistical description of surface roughness (Reeves 1985), energy considerations (Saeb 1990; Saeb and Amadei 1992; Amadei et al. 1998), anisotropy of the surface roughness (Jing et al. 1993), fractal theory (Kulatilake et al. 1995) and elasto-plasticity (Plesha 1987; Seidel and Haberfield 2002). Over the past few years, technical developments have shown that surface roughness can be accurately and easily characterised in three dimensions using high-resolution optical scanning measurements (Lanaro et al. 1998; Grasselli 2006). This approach led to new criteria that tried to explain rock joint shear strength behaviour based on three-dimensional quantification of surface roughness (Grasselli and Egger 2003; Yang et al. 2016; Dong et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017). More recently, the mechanical behaviour of rock joints has also been tackled from a semi-analytical stochastic perspective (Casagrande et al. 2018).

However, a major limitation of the aforementioned criteria is that they are either based on simplified joint profiles (Patton 1966; Ladanyi and Archambault 1969) or are only applicable to perfectly mated rock joints (Reeves 1985; Saeb 1990; Saeb and Amadei 1992; Amadei et al. 1998; Jing et al. 1993; Kulatilake et al. 1995; Plesha 1987; Seidel and Haberfield 2002; Grasselli and Egger 2003; Yang et al. 2016; Dong et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017; Casagrande et al. 2018), which is often not the case with natural rock joints in the field. One exception to the criteria above is Barton and Choubey’s empirical criterion. In the field, natural rock joints have undergone various geological processes, such as weathering or deformations in the rock mass. Due to these processes, natural rock joints normally exhibit a mismatch between the upper and lower surfaces. Barton and Choubey’s criterion has the capability of indirectly accounting for the matedness of natural rock joints when the JRC is estimated based on tilt tests. Nevertheless, it is not possible to separate the influence from matedness and roughness on the peak shear strength when using only the JRC parameter. Barton and Choubey’s empirical criterion was later revised by Zhao (1997a, b) who introduced the joint matching coefficient (JMC), which accounts for the matedness of natural rock joints. One limitation of this approach is that the estimation of the JMC is mainly performed by visual inspection and prediction of the percentage of the rock joint surfaces in contact. Therefore, the reliability of this parameter to express the matedness of natural rock joints is unclear.

In recent years, various attempts have been made to develop empirical and analytical criteria to increase understanding about how the matedness interacts with the surface roughness of a rock joint and contributes to the peak shear strength. During laboratory experiments, Johansson (2016) and Tang and Wong (2016) studied the mechanical behaviour of perfectly mated rock joints where the upper parts of the samples had been initially dislocated a certain shear displacement relative to the lower parts prior the shear tests. They used the relationship between the initial relative shear displacements prior the shear tests and the total length of the analysed rock joint samples to express the degree of matedness. However, Tang and Wong themselves recognised that imposing a dislocation on perfectly mated rock joints may not be realistic for natural, unmated rock joints in the field. Oh and Kim (2010) approached the matedness problem by theoretically studying the effect of opening on the shear behaviour of rock joints. Based on the geometric configuration of a regular, saw-tooth rock joint, they related the joint aperture with the degree of interlocking previously proposed by Ladanyi and Archambault (1969). This approach was later investigated in the laboratory by imposing a certain dislocation between the two contact surfaces of artificial rock joints with regular profiles (Li et al. 2016a, b) and incorporated in a new shear strength criterion based on fractal theory (Li et al. 2017). However, the ability to apply this criterion has not been verified against real, natural rock joints. Furthermore, their results are based on two-dimensional profiles and it is unclear how the criterion captures the three-dimensional characteristics of surface roughness of real rock joints.

The above review shows that a tested peak shear strength criterion for natural, unfilled rock joints that accounts for both the three-dimensional characteristics of surface roughness and the influence of matedness on peak shear strength is still lacking. Taking up this challenge, this paper presents a methodology that uses objective measurements of the average aperture between the joint surfaces of natural, unfilled rock joints to estimate their matedness. The measured average aperture utilised in this work is based on high-resolution optical scanning of the surface roughness. Furthermore, the relationship between the measured average aperture and the matedness of natural, unfilled rock joints has been integrated in a revised version of the peak shear strength criterion developed by Johansson and Stille (2014). Instead of using an initial shear displacement as a measure of the active asperities in contact, as was originally proposed by Johansson (2016), it is suggested that they are expressed in terms of the measured average aperture and the inclination of the active asperities in contact. The novelty of this approach lies in the use of measured average aperture of natural, unfilled rock joints based on high-resolution optical scanning to account for matedness as a step in the calculation of their peak shear strength.

2 Johansson and Stille’s Peak Shear Strength Criterion and Integration of the Average Aperture

2.1 Rationale of Johansson and Stille’s Peak Shear Strength Criterion

The peak shear strength criterion developed by Johansson and Stille (2014) for fresh, unweathered rock joints is based on the understanding of the different failure modes for a single asperity, the adhesion theory of friction and an idealised description of a rock joint surface roughness based on fractal theory. Furthermore, the criterion accounts for the change in the dilation angle at grain scale and the variation of the number and size of the active asperities at contact due to scale and matedness.

To understand how a single asperity can fail, Johansson and Stille (2014) studied the transition between different failure modes of an idealised asperity at different dilation angles (\(i\)), where the side of the asperity facing the shear direction was assumed to be subjected to a normal stress (\({\sigma }_{\mathrm{n}}^{{^{\prime}}}\)) equal to the uniaxial compressive strength of the intact rock (\({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\)). The results of the analysis showed that for low values of \(i\), it is sliding failure that controls the shear strength. At higher inclinations, shearing through the asperity becomes the governing failure mode. Finally, when the asperity inclination increases further, tensile failure occurs. They concluded that the value of \(i\), where the transition between sliding and shearing failure occurs, depends on the strength of the individual asperity. However, asperity inclinations above this transition value will not contribute to reach a higher mobilised shear strength. For this reason, according to Johansson and Stille (2014), the shear strength of a single asperity with a mobilised friction angle below the transition between sliding and shear failure can be expressed as was originally suggested by Patton (1966):

where \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) is the peak friction angle, \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) is the basic friction angle for a dry and sawn surface and \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) is the dilation angle at sample scale.

This peak shear strength criterion extends the analysis performed for a single asperity to sample scale based on the idea that surface roughness can be described with fractal theory (Mandelbrot 1985; Renard et al. 2006; Stigsson and Mas Ivars 2019). Based on this assumption, surface roughness may be idealised as a superposition of different asperities at multiple scales (i.e., with different heights and lengths). Furthermore, Brown (1987) and Malinverno (1990) both showed that a self-affine fractal profile keeps a power law relationship between the variation of the asperity height and the span of the measured profile. Taking up these findings, Johansson and Stille (2014) assumed that there also exists a scaling relationship between the asperity height (\({h}_{\mathrm{asp}}\)) and the asperity base length (\({L}_{\mathrm{asp}}\)) of different sized asperities on a rock joint profile. This scaling relationship is given by

where \({a}^{*}\) is an amplitude constant and \(H\) is the Hurst exponent.

In addition, for an idealised asperity there exists a geometric relation between the parameters \({h}_{\mathrm{asp}}\) and \({L}_{\mathrm{asp}}\), given by

By combining Eqs. (2) and (3), Johansson and Stille (2014) established an expression that relates the length and inclination of the asperities at contact, given by

Based on the adhesion theory, Johansson and Stille’s peak shear strength criterion assumes that for a given \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{n}}^{{^{\prime}}}\), the contact area (\({A}_{\mathrm{c}}\)) for a fresh and unweathered rock joint increases proportionally to the area of the sample (\(A\)). This can be expressed as

Previous observations on sheared rock joint surfaces have shown that the total contact area during the shearing process is only a small portion of the total area of the rock joint sample (Grasselli et al. 2002). Furthermore, these contact areas occur where the steepest asperities facing the shear direction are located (Kimura and Esaki 1995; Grasselli et al. 2002). After analysing a large number of scanning data from rock joint surfaces, Grasselli (2001) proposed the following empirical relationship to express the potential contact area ratio (\({A}_{\mathrm{c},\mathrm{p}}\)) at different asperity inclinations for a perfectly mated rock joint:

where \({A}_{0}\) is the maximum possible contact area ratio, \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\) is the maximum apparent dip angle in the shearing direction, \({\theta }^{*}\) is the apparent dip angle and \(C\) is a roughness parameter that governs the concavity of the curve.

For a fresh and unweathered rock joint, the value of \({A}_{\mathrm{c}}\) can be obtained by the product of \({A}_{\mathrm{c},\mathrm{p}}\) and \(A\). By combining the adhesion theory and the potential contact area ratio in Eqs. (5) and (6), Johansson and Stille (2014) suggested the following expression to estimate the dilation angle at grain scale (\({i}_{\mathrm{g}}\)) for a perfectly mated rock joint:

Johansson and Stille (2014) further discussed how the size of the asperities at contact varies due to scale and matedness. According to the adhesion theory, the ratio between \({A}_{\mathrm{c}}\) and \(A\) for a rock joint surface is only dependent on the applied \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{n}}^{{^{\prime}}}\) and its \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) [see Eq. (5)]. Consequently, this ratio is independent of scale, and the following expression can be derived:

The subscripts \(\mathrm{n}\) and \(\mathrm{g}\) in Eq. (8) indicate sample and grain size, respectively (Johansson and Stille 2014).

Furthermore, the true contact area is the sum of all the individual contact points on the rock joint which, together with Eq. (8), expresses how the number and size of the contact asperities on a rock joint change with the sample scale under constant normal load (CNL) conditions. Based on these assumptions, Johansson and Stille (2014) suggested an expression to estimate the average length of the asperities in contact at a size associated with sample size (\({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}\)), given by

where \({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{g}}\) is the average length of the asperities in contact at grain size, \({L}_{\mathrm{n}}\) is the length of the sample, \({L}_{\mathrm{g}}\) is the scale of the asperities associated with grain size and \(k\) is the matedness constant.

Finally, by combining Eqs. (2), (3), (4), (7) and (9), it is then possible to derive the equation that expresses \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\), given by

2.2 Integration of the Average Aperture to Account for Matedness

The peak shear strength criterion developed by Johansson and Stille (2014) has the ability of explaining how the compressive strength, roughness, scale and matedness of a fresh, unweathered rock joint surface interact to form the peak shear strength under CNL conditions. However, the criterion has only been tested against tensile induced rock joints (Johansson and Stille 2014; Johansson 2016).

The parameter \(k\) proposed by Johansson and Stille (2014) describes how the number and size of the active asperities taking part in the shearing process between two joint surfaces vary proportionally with shear displacement. The value of this parameter varies between 0 for a rock joint with perfect match and 1 for a totally mismatched rock joint. The equation for \(k\) is given by

where \(u\) is the total shear displacement at the peak (Johansson 2016).

During laboratory experiments on perfectly mated rock joints, Johansson (2016) proposed a relationship between an initial relative shear displacement or dislocation between lower and upper parts prior the shear test (\({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\)) and the length of the analysed rock joint sample. This relationship was used to estimate \(k\) with Eq. (11). According to Johansson (2016), for a perfectly mated rock joint, the size of the active asperities at contact at peak shear strength is associated with grain scale, \({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}={L}_{\mathrm{g}}\). This means that when using Eq. (11), \(k=0\), and consequently, the peak shear strength in a shear test occurs at a \(u={L}_{\mathrm{g}}/2\). Conversely, for a rock joint sample where the upper and lower surfaces have undergone a certain displacement \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\), the number of contact points decreases, and the size of the asperities at contact increases. This also means that an additional shear displacement (\(\Delta u\)) in the performed shear test is needed to reach the peak shear strength of the analysed unmated rock joint. As a result, \({u=u}_{\mathrm{i}}+\Delta u\), and the parameter \(k\) differs from 0 in these cases. Based on the principles of self-affine fractal theory and the idealisation of surface roughness as a superposition of different asperities at multiple scales, Johansson (2016) explained that it is reasonable to assume that a direct association exists between \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) of an unmated rock joint and the average length of the asperities in contact during the shearing process (\({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}\)). Johansson (2016) further explained that due to the association between \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) and \({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}\), the additional deformation \(\Delta u\) that is needed to reach the peak must also be directly proportional to \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) and \({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}\). The additional deformation of \(\Delta u\) required to reach the peak shear strength therefore becomes equal to \({L}_{\mathrm{asp},\mathrm{n}}/2\). This implies that \(\Delta u={u}_{\mathrm{i}}\), leading to \(u={2u}_{\mathrm{i}}\). The limitation of this assumption is connected to the possibility of describing surface roughness using self-affine fractal theory. For instance, this assumption should not be applied to predict the peak shear strength of blasted joint surfaces, saw-tooth rock joints or rock-concrete contact surfaces.

However, a drawback of the approach introduced by Johansson (2016) to account for the matedness is that it cannot be used with natural, unmated rock joints that exhibit an aperture. The main reason for this is that the estimation of \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) is in itself difficult when calculation of the peak shear strength of natural rock joints in the field is intended.

To account for this, we propose a revised version of Johansson and Stille’s peak shear strength criterion. This revised peak shear strength criterion incorporates the use of objective measurements of a natural rock joint average aperture (\(a\)) to account for its matedness as a step in the calculation of its \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\). In this new approach, it is suggested that the natural rock joint is assumed to be equal to an initially perfectly mated rock joint where the upper and lower parts have been dislocated a certain \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\). If sliding along active asperities is assumed, this virtual \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) in the perfectly mated rock joint will lead to changes in the aperture until a value of \(a\) equal to the one measured in the natural rock joint is reached. This principle is illustrated in Fig. 1. Additionally, this implies that aperture changes may theoretically be associated with the inclination of the active asperities in contact that contributes to the peak shear strength. By extension, this means that if \(a\) for a natural rock joint is known, a virtual \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) can be estimated by applying the relationship suggested by Ladanyi and Archambault (1969) and Oh and Kim (2010):

Since it can be assumed that \(u={2u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) as described above, the parameter \(k\) in Eq. (11) can be redefined as

Therefore, the revised peak shear strength criterion uses measurements of \(a\) to estimate \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) and \(k\) by performing an iterative process with Eqs. (7), (10) and (13) and calculating \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with Eq. (1).

3 General Methodology

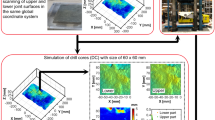

To investigate the ability of this new approach to account for the matedness of natural, unfilled rock joints using their measured \(a\) when calculating their \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion, a series of laboratory direct shear tests was conducted under CNL conditions. The main steps described in this section are supported by the flow chart in Fig. 2.

For each of the analysed rock joint samples, high-resolution optical scanning of the joint surfaces was performed prior to the direct shear tests to capture the roughness. Based on the information from the optical scanning, the three parameters describing surface roughness at grain scale (\({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\)) were derived. Together with the applied \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{n}}^{^{\prime}}\) and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) of the joint surfaces, it enabled the estimation of \({i}_{\mathrm{g}}\) using Eq. (7). By superposing the digitised upper and lower joint surfaces, aperture measurements for the analysed rock joints were objectively obtained. Based on the measured \(a\) and application of Eqs. (10) and (13), \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) and \(k\) were estimated. Finally, \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) was calculated using Eq. (1). These results were compared with the measured values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) obtained in the laboratory direct shear tests to test the revised criterion.

4 Description of Rock Joint Samples and Surface Characterization

4.1 Rock Joint Samples

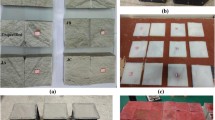

The analysed rock joint samples were obtained by over-drilling through an existing rock joint adjacent to the foundation of the Storfinnforsen buttress dam. The intact rock beneath the dam’s foundation consists of grey coarse-grained granite. Figure 3 shows two of the analysed samples from Storfinnforsen.

Additionally, two rock joint samples taken from an existing rock joint adjacent to the foundation of the Långbjörn concrete dam were included in this analysis. These rock joint samples consisted of grey coarse-grained granite and were slightly weathered. These samples were previously sheared in the laboratory by Johansson (2009).

The dimensions of the natural, unfilled rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen (S1 to S8) and Långbjörn (L1 and L2), together with the test conditions during the direct shear tests, are shown in Table 1.

4.2 Optical Scanning and Parameters for the Description of Surface Roughness

High-resolution optical scanning of the rock joints from Storfinnforsen (S1 to S8) was performed with an ATOS Compact Scan 5M system. The performed measurements on these eight samples had an accuracy of ± 0.02 mm. The rock joint samples from Långbjörn (L1 and L2) were scanned with an ATOS III system by Johansson (2009). The measurements of these two samples had an accuracy of ± 0.05 mm. Before performing the direct shear tests, the upper and lower joint surfaces were scanned separately. The upper and lower parts of each rock joint sample were then put together and scanned again, making it possible to analyse the degree of contact between both surfaces prior to the direct shear tests. To maintain consistency with the global reference system, circular reference points were placed around the upper and lower parts of all analysed samples, see Fig. 3. The scanned rock joint surfaces were re-generated with a resolution of 0.3 by 0.3 mm. This resolution was assumed to be appropriate to capture \({L}_{\mathrm{g}}\) on the rock joints according to previous recommendations by Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Tatone and Grasselli (2009). The parameters \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\) for the analysed joint surfaces were determined based on the digitised surfaces using the following methodology: first, normal vectors (\({{\varvec{n}}}_{\mathbf{i}}\)) were generated for each element on the 0.3 by 0.3 mm grid. By defining the shear direction (\({\varvec{t}}\)), the values of \({\theta }^{*}\) for each asperity facing the shear test direction were determined using

This principle is illustrated in Fig. 4a. As an example, the measured values of \({\theta }^{*}\) with respect to the defined \({\varvec{t}}\) for the lower and upper parts of sample S1 are illustrated in Fig. 4b, c, respectively. The calculated values of \({\theta }^{*}\) for the lower and upper parts of each rock joint sample were sorted separately in descending order. For each \({\theta }^{*}\), the parameter \({A}_{\mathrm{c},\mathrm{p}}\) defined as the sum of all the areas with a certain inclination facing the shear direction was determined using Eq. (6). Measured values of the relationship between \({\theta }^{*}\) and \({A}_{\mathrm{c},\mathrm{p}}\) for the lower and upper surfaces of sample S1 at a resolution of 0.3 by 0.3 mm are shown in Fig. 4d. Data from these two curves were used to calculate \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\) by best-fit regression analysis [see Eq. (6)]. Table 2 presents the results of the regression analysis for the analysed rock joint samples.

a Geometrical representation of the definition of \({\theta }^{*}\) of an asperity for a given \({\varvec{t}}\); b measured values of \({\theta }^{*}\) with respect to the defined \({\varvec{t}}\) for the lower part of sample S1; c measured values of \({\theta }^{*}\) with respect to the defined \({\varvec{t}}\) for the upper part of sample S1; d relationship between measured values of \({A}_{\mathrm{c},\mathrm{p}}\) and \({\theta }^{*}\) for the lower and upper parts of sample S1 and the obtained regression analysis

The relationship between \({h}_{\mathrm{asp}}\) and \({L}_{\mathrm{asp}}\) established in Eq. (3) was estimated by calculating the root mean square of the first derivative (\({Z}_{2}\)) for different sampling intervals along the shear direction (\(\Delta x\)) in the digitised joint surfaces. Each digitised joint surface was divided into profiles separated by a constant distance perpendicular to the shear direction (\(\Delta y\)). The parameter \({Z}_{2}\) describes therefore the average inclination of the asperities over a certain \(\Delta x\) and for each profile separated a distance \(\Delta y\). This can be expressed as

where \({N}_{x}\) and \({N}_{y}\) are the number of coordinate points over a digitised rock joint surface parallel and perpendicular to the shear direction, respectively. The pairs \(\left({x}_{i,j}, {z}_{i,j}\right)\) and \(\left({x}_{i+1,j}, {z}_{i+1,j}\right)\) are adjacent coordinates in the same profile along the shear direction separated by a constant distance \(\Delta x\) (Myers 1962).

The values of \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta y\) were equal and varied between 0.3 mm and 9.6 mm for the digitised rock joint surfaces. As an example, Table 3 shows the results of the calculation of \({h}_{\mathrm{asp}}\) for different \({L}_{\mathrm{asp}}\) for sample S1. Based on these results, the values of \(H\) for the analysed rock joint samples were determined through regression analysis using Eq. (2).

Additionally, the aperture of all the tested rock joint samples was measured after superposing the lower and upper digitised surfaces and calculating the difference in elevation between points with same \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates. This was possible since both upper and lower joint surfaces of the tested rock samples were scanned in the same global reference system. Figure 5 shows the rock joint aperture for sample S1. After calculating the difference in elevation for each point in the upper and lower digitised surfaces the parameter \(a\) was obtained by

where \({z}_{i,j}^{\mathrm{upper}}\) and \({z}_{i,j}^{\mathrm{lower}}\) are the elevation of two points with same \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates situated in the upper and lower digitised surfaces with a resolution of 0.3 by 0.3 mm, respectively.

The values of \(H,\) together with the measurements of \(a\) and the estimation of \(k\) and \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) for the analysed rock joints, are shown in Table 4.

5 Laboratory Shear Test Procedure

The rock joint samples were sheared at Luleå University of Technology. The direct shear tests were conducted in a servo-controlled shear machine with the capacity to perform shear tests according to the methodology suggested by ISRM (Muralha et al. 2014). The normal and shear capacity of this machine is 500 kN. As previously mentioned, the direct shear tests on rock joint samples L1 and L2 were conducted by Johansson (2009) in the same shear test machine.

A summary of the preparation process prior the shear tests is illustrated in Fig. 6. The shear tests were performed at a shear displacement rate of 0.1 mm/minute until reaching a maximum shear displacement of 5 mm. The nominal contact area between the upper and lower parts of the joint surfaces was continuously updated by considering its reduction due to the relative shear displacement. In addition, both loads and displacements were continuously monitored in the shear and normal directions during the shear tests. Loads were measured with load cells and displacements were measured with LVDTs. In the normal direction, normal displacements (\({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\)) were measured with four LVDTs, two on each side of the sample. In the shear direction, the shear displacement (\({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\)) was measured with two LVDTs installed at the front of the sample, one on each side. A detailed picture taken sideways with the arrangement of the installed LVDTs on one of the tested rock joint samples is illustrated in Fig. 6d. The utilised LVDTs measured displacements on the range of 0–25 mm and had an accuracy of better than 0.1%. Data were registered during the conducted shear tests at an interval of 0.5 s. The average values of the registered data of \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) and \({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) were used to calculate the value of \(i\) for each of the tested rock joint samples using

Preparation of the analysed rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen: a levelling of one of the analysed rock joint samples to keep it horizontal; b casting of the rock joint samples with concrete; c rock joint sample S4 being placed in the shear machine; d rock joint sample S4 ready for shearing with mounted LVDTs

A constant increment in the shear direction (\({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\)) of 0.1 mm was used in the calculation of \(i\).

6 Shear Test Results and Verification of the Revised Peak Shear Strength Criterion

6.1 Shear Test Results

Conventionally, the results of direct shear tests are presented by plotting shear stress and normal displacement versus shear displacement (Muralha et al. 2014). However, the revised peak shear strength criterion expresses the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) in degrees. To maintain consistency in the comparison between the conducted shear tests and the predicted \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of the analysed rock joint samples with the revised criterion, plots containing mobilised friction angle (\(\phi\)) versus \({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) have been presented in this study.

The results of \(\phi\) and \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) versus \({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) measured during the laboratory direct shear tests conducted on the analysed rock joint samples are presented in Fig. 7. Additionally, values of measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\), dilation angle at the peak (\({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\)) and shear displacement at the peak (\({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\)) are presented in Table 5. Rock joint samples S1 to S8 showed a measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) varying between 50.5° and 71.8°. On average, the measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) was 59.3°. These rock joint samples showed a measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) between 9.0° and 35.1°. The measured values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) and \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) were 44.6° and 7.3° for sample L1, and 42.4° and 7.6° for L2.

Two different mechanical behaviours were observed when comparing the measured \(\phi\) versus \({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) of the analysed rock joint samples (see Fig. 7a). The results of the direct shear tests for samples S1, S3, S4 and S5 showed a clear peak and post-peak behaviour. For these rock joint samples, the registered \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) varied between 0.26 and 1.2 mm (see Table 5). On the contrary, samples S2, S6, S7 and S8 had a smoother transition into post-peak behaviour and a clear peak could not be observed. The registered \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) for these samples varied between 0.69 and 4.1 mm. The rock joint samples L1 and L2 showed also a smooth transition into post-peak behaviour with a registered \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) of 3.22 and 2.20 mm, respectively. This observed mechanical behaviour with a smooth transition into post-peak shear strength is consistent with other results reported by Johansson (2009, 2016) on unmated rock joints.

The comparison between measured \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) versus \({\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) in Fig. 7b showed a similar mechanical behaviour for all the analysed rock joint samples. The results showed an initial closure followed by a relative opening between the lower and upper parts of the analysed samples. The measured \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) at 5 mm shear displacement varied between 0.9 and 2.1 mm for samples S1 to S8. Samples L1 and L2 had a measured \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) of 0.24 and 0.31 mm, respectively. Sample L1 was sheared 4 mm and sample L2 was sheared 5 mm. In comparison with samples S1 to S8, samples L1 and L2 had a lower measured \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\). The observed mechanical behaviour of L1 and L2 was as expected since they presented a smoother surface roughness and a higher measured \(a\) than samples S1 to S8 (see Tables 2, 4).

6.2 Verification of the Revised Peak Shear Strength Criterion

A comparison between calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion and measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) in the laboratory for the analysed rock joint samples is presented in Fig. 8a. The value of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) obtained by means of tilt tests was estimated as 31° for the analysed rock joint samples (S1 to S8, L1 and L2). The \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) of these ten rock joint samples was estimated using the Schmidt Hammer Index as suggested by Barton and Choubey (1977). The \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) obtained for samples S1 to S8 was 110 MPa. Rock joint samples L1 and L2 had a \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) of 140 MPa (Johansson 2009). The applied \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{n}}^{{^{\prime}}}\) on the analysed rock joints is presented in Table 1. Parameters \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\) are provided in Table 2. Values of \(H\), \(a\), \(k\) and \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) are provided in Table 4.

Comparison between calculated and measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) and obtained linear fit through regression analysis for the rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen, Långbjörn (Johansson 2009) and Flivik (Johansson 2016): a calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised peak shear strength criterion and Johansson (2016); b calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the peak shear strength criteria previously developed by Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014)

The calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion were in good agreement with the results from the direct shear tests conducted in the laboratory. The results show that for samples S1 to S8, the calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) varied between 52.4° and 64.7°. The average value of the calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) on these samples with the revised criterion was 58.0°. The difference between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\), as expressed in absolute values, varied between 0.4° and 4.8°. The exception was sample S3, which showed a less good agreement. In this rock joint sample, the difference between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) was 9.3°. Samples L1 and L2 had a calculated value of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of 41.1° and 47.6°, respectively. For these two samples, the difference between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\), as expressed in absolute values, was 3.5° and 5.2°, respectively.

To increase the completeness of this study, Fig. 8a also includes the results from six direct shear tests previously performed by Johansson (2016) on fresh tensile-induced rock joints with dimensions of 60 by 60 mm and 200 by 200 mm. These rock joint samples came from the Flivik quarry in Sweden and consisted of grey coarse-grained granite. The values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) were predicted using the peak shear strength criterion developed by Johansson and Stille (2014) with \(k=0\). This assumption is considered reasonable, since tensile-induced rock joints exhibit a perfect match between the upper and lower parts (Johansson 2016). The main reason for including them in this analysis is to provide a comparison between three different groups of rock joints with different joint matedness. In total, the comparison between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) comprises 16 rock joint samples.

7 Discussion

7.1 Comparison Between Calculated and Measured Peak Shear Strength

The analysis performed on the rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen (S1 to S8) showed that the calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion were in good agreement with the measured values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) in the laboratory. However, the comparison between calculated and measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) for sample S3 deviated from the expected behaviour. The reason for this discrepancy (9.3°) is not clear. During the laboratory shear tests, the observed \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) for this sample was 0.36 mm. The measured \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) gives an indication of the size of the effective asperities contributing to the shear resistance at the peak. The results from the laboratory direct shear tests on the six perfectly mated rock joints performed by Johansson (2016) showed an average \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) of approximately 0.3 mm. This may indicate that the joint surfaces of sample S3 had similar conditions to a perfectly mated rock joint. Consequently, the application of the methodology proposed in this paper might underestimate the matedness of sample S3, leading to a larger discrepancy between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\).

The comparison between measured and calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) for the rock joint samples from Långbjörn (L1 and L2) was also in good agreement. Note that the revised criterion was able to predict well the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of samples L1 and L2, which, compared with the other group of analysed rock joints (S1 to S8), had a higher degree of weathering, a lower \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) and a higher registered \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) measured in the laboratory (see Fig. 7a). The reason for this is that L1 and L2 had, on average, higher values of \(C\) in combination with lower values of \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\) than samples S1 to S8 (see Table 2). Higher values of \(C\) are associated with low surface roughness where a large portion of the asperities facing the shear direction is less steep than \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\) (Grasselli 2001). In addition, L1 and L2 had a high measured \(a\), which led to high values of \(k\) and low values of \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) (see Table 4). This combination between \(C\), \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\) and \(a\) shows how surface roughness interacts with the matedness in the revised criterion to form \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\). Furthermore, these results also show how the description of surface roughness using self-affine fractal theory and the direct association between asperities at multiple scales is accounted for in the revised criterion. As it is observed in Fig. 7a, b, the analysed rock joint samples with higher measured \(a\) had a higher registered \({\delta }_{\mathrm{peak}}\) and a lower \({\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) at maximum shear displacement.

The calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) for the rock joint samples from Flivik were also in good agreement with the results from the direct shear tests conducted in the laboratory by Johansson (2016).

A discrepancy was observed when comparing the measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) during the conducted direct shear tests and the calculated \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) with the revised criterion of the analysed rock joint samples. The average values of measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) and calculated \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) for all ten samples were 18.4° and 24.3°, respectively (see Tables 4, 5). The average calculated \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) was 5.9° higher than the average measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\). A possible reason for this discrepancy between measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) and calculated \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) may be due to the existence of an asperity failure component in the performed shear tests. The peak shear strength criterion by Johansson and Stille (2014) and the revised criterion both assume that sliding along the active asperities is the predominant failure mode governing the shearing process. However, the contribution from an asperity failure component is close to the contribution from sliding—at least under the assumption that the contact pressure on the asperities is equal to \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) (Johansson and Stille 2014; Johansson 2016). Therefore, even though a discrepancy was observed between average \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) and \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\), the comparison between measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) will show a good agreement. Furthermore, this discrepancy will not influence the calculation of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion, since the calculation of \(k\) and \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) originates from an initial measured \(a\) of the natural rock joint.

A similar discrepancy could also be observed when comparing the average values of measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}-{i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) (37.8°) with \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) (31°) measured in the tilt tests (see Table 5). The average measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}-{i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) was 6.8° higher than the measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\). This discrepancy may be due to the existence of an asperity failure component as previously discussed. Another possible reason is an uncertainty in the measurements of \(i\) in the performed shear tests since it is influenced by the selected \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\). The values of \(i\) were calculated with a constant \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) of 0.1 mm. Selecting a value of \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) higher than 0.1 mm will result in lower values of measured \(i\) in the performed shear tests. On the other hand, values of \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) lower than 0.1 mm will result in a large scattering when measuring \(i\) since the measured \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{n}}\) for each \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) is becoming close to the accuracy of the installed LVDTs. Additionally, Johansson (2016) suggested that it is necessary that the selected \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) to calculate \(i\) from the shear tests is of the same magnitude as the micro-scale roughness of the sawn samples used to determine \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) with tilt tests in order for them to be compatible. The ISRM Suggested Method for determining \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) recommends using saw blades with teeth or rim grits on the range of 60–100 US Mesh during the specimen preparation (Alejano et al. 2018). Bruce et al. (1989) also observed that reasonable values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) for quartzite and dolostone were obtained when their surfaces were roughened with a No. 80 grit. They observed that the roughness of the prepared plates had a Centre Line Average (CLA) of 200 µm for the quartzite and 150 µm for the dolostone. The selected \({\mathrm{d}\delta }_{\mathrm{s}}\) (100 µm) for the calculation of \(i\) in the performed shear tests in this study is in the same range as the observed values of CLA by Bruce et al. (1989) and therefore it is considered suitable for the measurements of \(i\). The uncertainties in the measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) and the compatibility between \({\phi }_{\mathrm{b}}\) and \(i\) may also be a possible reason for the observed discrepancy between measured \({i}_{\mathrm{peak}}\) during the conducted direct shear tests and the calculated \({i}_{\mathrm{n}}\) previously discussed.

7.2 Influence of the Aperture on the Peak Shear Strength

To study the influence of \(a\) on the estimation of \(k\) and the calculation of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the revised criterion, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This sensitivity analysis included samples S1 to S8, L1 and L2. Figure 9 shows the variation of \(k\) and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with different values of measured \(a\). The results showed that both the parameter \(k\) and the calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) showed steep variation when the measured \(a\) was within a range of between 0 and approximately 1 mm. For instance, for the values of \(a\) within the range between 0 and 1 mm, the parameter \(k\) increased between 0.42 and 0.67 in the analysed rock joint samples (see Fig. 9a). For the same range of \(a\), the calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) decreased between 7.9° and 13.9° for the analysed samples (see Fig. 9b). This variation in the estimated value of \(k\) and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) was less abrupt at higher ranges of the measured \(a\).

To increase the completeness of this sensitivity analysis, the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of the rock joint samples presented in this study was also calculated with the peak shear strength criteria previously developed by Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014). The input data required to apply these criteria to samples S1 to S8, L1, L2 and the perfectly mated rock joints from Flivik are provided in Tables 1, 2 and 4 and in the study performed by Johansson (2016). The peak shear strength criterion by Johansson and Stille (2014) was implemented in the analysed rock joint samples by setting the parameter \(k=0\). Since the upper and lower parts of the rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen and Långbjörn were not dislocated prior the laboratory shear tests, the values of \({u}_{\mathrm{i}}\) and \(k\) were equal to 0 according to Johansson (2016). A comparison was made between values of measured and calculated \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with the peak shear strength criteria by Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014), which is illustrated in Fig. 8b. The results for the perfectly mated rock joints from Johansson (2016) showed that the calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) obtained with Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014) peak shear strength criteria were in good agreement with the measured \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) in the laboratory. However, the comparison was less good for rock joint samples S1 to S8, L1 and L2. The calculated values of \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) with Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014) generally overestimated the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) measured in the laboratory. Furthermore, the slope of the obtained linear fit through regression analysis for the peak shear strength criteria from Grasselli and Egger (2003) and Johansson and Stille (2014) was 0.3 and 0.4, respectively. This is not surprising, since both criteria assume a perfect match between the lower and upper parts joints, which is not the case of the natural, unfilled rock joint samples presented in this study.

7.3 Prediction of in-situ Peak Shear Strength

The novelty of this paper lies in the use of high-resolution optical scanning to objectively derive \(a\) and to calculate the matedness of natural, unfilled rock joints as a step in the prediction of their \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\). However, there are still some issues concerning the suggested methodology which require further study before it can be applied in the field.

Using the equipment and measurement techniques currently available makes it possible to obtain the necessary information from visible rock exposures, for example in tunnels or from core-drilling through existing rock joints under a dam foundation. For instance, aperture measurements can be determined through Borehole Image Processing System (BIPS) of the boreholes. The resolution with this technique, however, is limited to approximately 0.5 mm. Therefore, BIPS might be more suitable for rock joints with larger apertures where the upper and lower surfaces of the joints are not in contact with each other, while high-resolution optical scanning could be used directly on core samples for rock joints with smaller aperture, where contact between the upper and lower surfaces exists.

Taken together with additional information from the rock core samples, such as roughness parameters (\({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\)), \(H\) and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) of the rock joint surfaces, these techniques might be sufficient to apply the methodology presented in this paper and to calculate \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) using the revised criterion. Furthermore, the information from the rock core samples would also be sufficient to account for surface anisotropy when applying the revised criterion. For instance, the parameters \({\theta }_{\mathrm{max}}^{*}\), \(C\) and \({A}_{0}\) presented in this study were calculated for a defined shear direction in the conducted direct shear tests. They would have been slightly different if another shear direction had been applied. In the field, it is therefore important to account for all potential shear directions when the rock joint surface roughness is characterised before the application of the revised criterion, unless the shear direction is known. The evaluation of roughness anisotropy using three-dimensional surface measurements can be done by applying the methodology described by Tatone and Grasselli (2009). The extent of the pre-investigations that need to be performed to realistically account for the aperture when predicting the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of large-scale natural rock joints is subject of further investigation. The size of a large-scale natural rock joint can be considered in the revised criterion by increasing the parameter that represents the sample size, \({L}_{\mathrm{n}}\).

A limitation with the current study is that the revised criterion has only been tested against coarse-grained granite samples. However, Johansson and Stille (2014) tested the criterion against perfectly mated rock joints of different rock types tested in the laboratory by Grasselli (2001). The results by Johansson and Stille (2014) showed a good agreement between measured and calculated contribution from roughness. The exception was the samples of gneiss, which deviated from the expected behaviour. According to Johansson and Stille (2014), this deviation was most likely due to the anisotropic \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{ci}}\) of the gneiss. They further explained that it was uncertain how the shear load during the direct shear tests performed by Grasselli (2001) had been applied with respect to the schistosity planes of the gneiss samples. The ability of the revised criterion to predict the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of natural, unfilled rock joints of other rock types is recommended to be further studied.

Finally, the original criterion by Johansson and Stille (2014) was developed to assess the safety of concrete dams against sliding in the rock foundation under low normal stress to joint compressive strength ratios, which are typical in civil engineering applications. In this paper, all samples were tested with low normal stress to joint wall compressive strength ratios of approximately 0.01. The ability of the proposed methodology together with the revised criterion to predict the \({\phi }_{\mathrm{p}}\) of natural, unfilled rock joints under higher normal loads needs to be further studied to verify its applicability under such conditions.

8 Conclusions

In this paper we present a revised peak shear strength criterion with the ability to account for both the three-dimensional characteristics of the surface roughness and the matedness of natural, unfilled rock joints. Based on the performed analysis and experiments in the laboratory, it can be concluded that the revised peak shear strength criterion is able to predict the peak shear strength of natural, unfilled rock joints under the conditions tested in this study.

The revised peak shear strength criterion uses a new methodology where objective measurements of the average aperture between the joint surfaces of natural, unfilled rock joints derived from high-resolution optical scanning are used to estimate their matedness, as a step in the calculation of their peak shear strength. The main benefit of this approach is that aperture measurements can be obtained directly from visible rock mass exposures or from core-drilling. This makes it possible to account for the influence of matedness on the peak shear strength of natural, unfilled rock joints under conditions where this otherwise is difficult to assess, such as the rock foundation under an existing concrete dam.

All samples were tested with low normal stress to joint wall compressive strength ratios of approximately 0.01. It is therefore recommended that further studies are conducted at higher levels of normal stress to joint wall compressive strength ratios to assess the applicability of the revised criterion under such conditions. The methodology presented in this paper has not yet been applied to large-scale natural, unfilled rock joints in the field. Further studies are required to study the applicability of the revised peak shear strength criterion at larger scales in-situ.

Abbreviations

- ATOS:

-

Advanced topometric optical sensor

- BIPS:

-

Borehole image processing system

- CNL:

-

Constant normal load

- JRC :

-

Joint roughness coefficient

- JMC :

-

Joint matching coefficient

- LVDT:

-

Linear variable differential transformer

- a :

-

Rock joint average aperture

- a * :

-

Amplitude constant based on asperity base length

- A :

-

Area of the rock joint sample

- A 0 :

-

Maximum potential contact area ratio

- A c :

-

Total contact area

- A c,p :

-

Potential contact area ratio

- C :

-

Roughness parameter

- h asp :

-

Asperity height

- H :

-

Hurst exponent

- i :

-

Dilation angle

- i g :

-

Dilation angle at grain scale

- i n :

-

Dilation angle at sample scale

- i peak :

-

Dilation angle at the peak shear strength

- k :

-

Matedness constant

- L asp :

-

Asperity base length

- L asp,g :

-

Average length of the asperities in contact at size associated with grain size

- L asp,n :

-

Average length of the asperities in contact at size associated with sample size

- L g :

-

Scale of the asperities associated with grain size

- L n :

-

Length of the rock joint sample at full scale

- n :

-

Normal vector to the joint surface

- N x :

-

Coordinate points over a digitised joint surface parallel to shear direction

- N y :

-

Coordinate points over a digitised joint surface perpendicular to shear direction

- R 2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- t :

-

Shear vector

- u :

-

Total shear displacement at the peak shear strength

- u i :

-

Initial shear displacement before a shear test

- Z 2 :

-

Root mean square of the first derivate of the joint surface

- δ n :

-

Normal displacement

- δ peak :

-

Shear displacement at peak shear strength

- δ s :

-

Shear displacement

- Δu :

-

Additional shear displacement to reach the peak shear strength

- Δx :

-

Sampling distance parallel to shear direction

- Δy :

-

Sampling distance perpendicular to the shear direction

- θ * :

-

Apparent dip angle

- \(\theta_{\rm max }^{*}\) :

-

Maximum apparent dip angle

- σ ci :

-

Uniaxial compressive strength of the joint surface

- \(\sigma_{\rm n}^{\prime }\) :

-

Effective normal stress

- ϕ :

-

Mobilised friction angle

- ϕ b :

-

Basic friction angle

- ϕ p :

-

Peak friction angle

References

Alejano L, Muralha J, Ulusay R et al (2018) ISRM suggested method for determining the basic friction angle of planar rock surfaces by means of tilt tests. Rock Mech Rock Eng 51:3853–3859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1627-6

Amadei B, Wibowo J, Sture S, Price R (1998) Applicability of existing models to predict the behavior of replicas of natural fractures of welded tuff under different boundary conditions. Geotech Geol Eng 16:79–128. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008886106337

Barton N (1973) Review of a new shear-strength criterion for rock joints. Eng Geol 7:287–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7952(73)90013-6

Barton N, Choubey V (1977) The shear strength of rock joints in theory and practice. Rock Mech 10:1–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01261801

Brown SR (1987) A note on the description of surface roughness using fractal dimension. Geophys Res Lett 14:1095–1098. https://doi.org/10.1029/GL014i011p01095

Bruce IG, Cruden DM, Eaton TM (1989) Use of a tilting table to determine the basic friction angle of hard rock samples. Can Geotech J 26:474–479. https://doi.org/10.1139/t89-060

Casagrande D, Buzzi O, Giacomini A, Lambert C, Fenton G (2018) A new stochastic approach to predict peak and residual shear strength of natural rock discontinuities. Rock Mech Rock Eng 51:69–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1302-3

Dong H, Guo B, Li Y, Si K, Wang L (2017) Empirical formula of shear strength of rock fractures based on 3D morphology parameters. Geotech Geol Eng 35:1169–1183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-017-0172-5

Grasselli G (2001) Shear strength of rock joints based on quantified surface description. Doctoral Thesis, Lausanne, EPFL

Grasselli G (2006) Manuel Rocha medal recipient shear strength of rock joints based on quantified surface description. Rock Mech Rock Eng 39:295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-006-0100-0

Grasselli G, Egger P (2003) Constitutive law for the shear strength of rock joints based on three-dimensional surface parameters. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 40:25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00101-6

Grasselli G, Wirth J, Egger P (2002) Quantitative three-dimensional description of a rough surface and parameter evolution with shearing. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 39:789–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00070-9

Jing L, Stephansson O, Nordlund E (1993) Study of rock joints under cyclic loading conditions. Rock Mech Rock Eng 26:215–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01040116

Johansson F (2009) Shear Strength of Unfilled and Rough Rock Joints in Sliding Stability Analyses of Concrete Dams. Doctoral Thesis TRITA-JOB-PHD-1013, Stockholm, KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Johansson F (2016) Influence of scale and matedness on the peak shear strength of fresh, unweathered rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 82:36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2015.11.010

Johansson F, Stille H (2014) A conceptual model for the peak shear strength of fresh and unweathered rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 69:31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2014.03.005

Kimura T, Esaki T (1995) A new model for the shear strength of rock joint with irregular surfaces. In: Int. Proc. Symp. Mechanics of Jointed and Faulted Rock, 1995. pp 133–138

Kulatilake P, Shou G, Huang T, Morgan R (1995) New peak shear strength criteria for anisotropic rock joints. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 32:673–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(95)00022-9

Ladanyi B, Archambault G (1969) Simulation of shear behavior of a jointed rock mass. In: The 11th US Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), 1969. American Rock Mechanics Association

Lanaro F, Jing L, Stephansson O (1998) 3-D-laser measurements and representation of roughness of rock fractures. Mechanics of jointed and faulted rock, 1998. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 185–189

Li Y, Oh J, Mitra R, Hebblewhite B (2016a) Experimental studies on the mechanical behaviour of rock joints with various openings. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49:837–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0781-3

Li Y, Oh J, Mitra R, Hebblewhite B (2016b) Modelling of the mechanical behaviour of an opened rock joint. In: Ulusay et al. (Eds) Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering: from the Past to the Future. Taylor & Francis Group, London, pp 451–456

Li Y, Oh J, Mitra R, Canbulat I (2017) A fractal model for the shear behaviour of large-scale opened rock joints. Rock Mech Rock Eng 50:67–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1088-8

Liu Q, Tian Y, Liu D, Jiang Y (2017) Updates to JRC-JCS model for estimating the peak shear strength of rock joints based on quantified surface description. Eng Geol 228:282–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2017.08.020

Malinverno A (1990) A simple method to estimate the fractal dimension of a self-affine series. Geophys Res Lett 17:1953–1956. https://doi.org/10.1029/GL017i011p01953

Mandelbrot BB (1985) Self-affine fractals and fractal dimension. Phys Scr 32:257

Muralha J, Grasselli G, Tatone B, Blümel M, Chryssanthakis P, Yujing J (2014) ISRM suggested method for laboratory determination of the shear strength of rock joints: revised version. Rock Mech Rock Eng 47:291–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-013-0519-z

Myers N (1962) Characterization of surface roughness. Wear 5:182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(62)90002-9

Oh J, Kim G-W (2010) Effect of opening on the shear behavior of a rock joint. Bull Eng Geol Environ 69:389–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-010-0271-5

Patton FD (1966) Multiple modes of shear failure in rock. In: 1st ISRM Congress, 1966. International Society for Rock Mechanics

Plesha ME (1987) Constitutive models for rock discontinuities with dilatancy and surface degradation. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech 11:345–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.1610110404

Reeves M (1985) Rock surface roughness and frictional strength. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 22:429–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(85)90007-5

Renard F, Voisin C, Marsan D, Schmittbuhl J (2006) High resolution 3D laser scanner measurements of a strike-slip fault quantify its morphological anisotropy at all scales. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL025038

Saeb S (1990) A variance of the Ladanyi and Archambault’s shear strength criterion. International symposium on rock joints, Loen, 1990. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 701–705

Saeb S, Amadei B (1992) Modelling rock joints under shear and normal loading. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr 29:267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(92)93660-C

Seidel JP, Haberfield CM (2002) A theoretical model for rock joints subjected to constant normal stiffness direct shear. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 39:539–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00056-4

Stigsson M, Mas Ivars D (2019) A novel conceptual approach to objectively determine JRC using fractal dimension and asperity distribution of mapped fracture traces. Rock Mech Rock Eng 52:1041–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1651-6

Tang ZC, Wong LNY (2016) New criterion for evaluating the peak shear strength of rock joints under different contact states. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49:1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0811-1

Tatone BS, Grasselli G (2009) A method to evaluate the three-dimensional roughness of fracture surfaces in brittle geomaterials. Rev Sci Instrum 80:125110. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3266964

Yang J, Rong G, Hou D, Peng J, Zhou C (2016) Experimental study on peak shear strength criterion for rock joints. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49:821–835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0791-1

Zhao J (1997) Joint surface matching and shear strength part A: joint matching coefficient (JMC). Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34:173–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(96)00062-9

Zhao J (1997) Joint surface matching and shear strength part B: JRC-JMC shear strength criterion. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 34:179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-9062(96)00063-0

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper was supported by the Swedish Hydropower Centre (SVC) (Grant No. VK10798). SVC was established by the Swedish Energy Agency, Elforsk and Svenska Kraftnät together with Luleå University, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Chalmers University of Technology and Uppsala University. http://www.svc.nu. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (SKB) (order number 22483). The authors thank Carl Oscar Nilsson at Uniper for providing the rock joint samples from Storfinnforsen.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ríos-Bayona, F., Johansson, F. & Mas-Ivars, D. Prediction of Peak Shear Strength of Natural, Unfilled Rock Joints Accounting for Matedness Based on Measured Aperture. Rock Mech Rock Eng 54, 1533–1550 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02340-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02340-8