Abstract

The breaking features and stress distribution of overlying strata in a steeply dipping coal seam (SDCS) differ significantly from those in a near-horizontal one. In this study, the laws governing the evolution of vertical stress release and shear stress concentration in the overlying strata of coal seams with different dip angles are derived via numerical simulation, rock mechanics tests, acoustic emissions, and field measurements. Thus, the stress-driven dynamic evolution of the overlying strata structure, in which a shear stress arch forms, is determined. Upon breaking the lower part of the overlying strata, the shear stress transfers rapidly to the upper part of the working face. The damaged zone of the overlying strata migrates upward along the dip direction of the working face. The gangue in the lower part of the working face is compacted, leading to an increase in vertical stress. As the dip angle of the coal seam increases, the overlying strata fail suddenly under the action of shear stresses. Finally, the behavioral response of the overlying strata driven by shear stresses in the longwall working face of an SDCS is identified and analyzed in detail. The present research findings reveal the laws governing the behavior of mine pressure in the working face of an SDCS, which in turn can be used to establish the respective on-site guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Producing high-quality coking coal and anthracite yields considerable economic gains (Tu et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2020). In China, over half of the production of these rare types of coal occurs in steeply dipping coal seams (SDCSs), which make up about 20% of the proven resources (Yun et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019, 2020). However, SDCS mining safety and efficiency are jeopardized by difficult geological structures and prevailing conditions, the complicated and coupled effects of which require further in-depth investigations (Kulakov 1995; Peng 2006; Wu et al. 2014; Das et al. 2017; Zuo et al. 2020). To date, theoretical studies on SDCS mining have concerned mainly (1) how the mine pressure is distributed, (2) the relationship between hydraulic support and surrounding rock, and (3) the breaking and migration features of the overlying strata. A finding regarding the distribution of mine pressure is asymmetric weighting along the dip direction of the working face during SDCS excavation (Yin et al. 2010; Deng and Wang 2014; Yang et al. 2015a, b; Chi et al. 2020). Using the relationship between hydraulic support and surrounding rock, some researchers developed a mechanical model of the instability of support along the dip direction of the working face under different working states (Wu and Yun 1999; Wang and Jiao 2016; Yang et al. 2018; Hu et al. 2018; Chi et al. 2019). Given that the breaking and migration features of the overlying strata are yet to be revealed accurately because of the undefined breaking process and the complexity of the SDCS mechanical features, the research progress in this direction can be reduced to the following achievements. By developing a mechanical model of the breaking of the overlying strata in the SDCS, the deflection and stress states of the main roof at different positions along the dip direction of the working face were determined, revealing asymmetric features of the caving of the main roof in the SDCS (Zhang et al. 2010; Zhang and Cao 2015; Wang et al. 2015; Lv et al. 2019). However, the limitations of the above mechanical model have led many scholars use physical similarity and numerical simulations to analyze the gangue slip and filling features after the caving of the overlying strata in the SDCS. Their studies of inclined and anti-inclined stacking structures during gangue slip along the SDCS led to identifying the asymmetric caving arch in the overlying strata (Gao 2004; Wu et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2015; Tu et al. 2017; Xie et al. 2019).

The research findings on the migration laws and structural patterns of the overlying strata in an SDCS, which were obtained worldwide using different methods, provide certain theoretical guidance for how to control the surrounding rock in the SDCS. However, only some of those studies concerned the dynamic evolution of the overlying strata when mining an SDCS (especially longwall mining) and the stress-driven mechanism for how such structures form. Consequently, the present study is aimed at improving the SDCS numerical model and performing a comprehensive combination of compression and field tests on precracked rock samples with different dip angles. From that, the law governing the evolution of the stress arch in the overlying strata of an SDCS is obtained, as is the dynamic evolution process of the overlying strata structure driven by stress. The present research findings are important for establishing guidance regarding safe SDCS excavation.

2 Mining and geological conditions

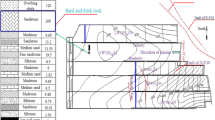

As a case study of an SDCS with dip angle exceeding 35°, we selected the 1212 (3) working face of the Panbei Coal Mine, which is located approximately 30 km northwest of the city of Huainan in the province of Anhui in China. Covering approximately 15.0 km2, the mining area is 7.5 km long and 1.3–2.7 km wide. The coal seam is at a depth of 375–495 m, has a dip angle of 35°–50°, is 4 m thick on average, and is stable. The immediate roof is mostly mudstone and sandy mudstone; its thickness varies between 2.5 and 6.8 m with an average of 4.7 m. The direct floor is mudstone, with an average thickness of 3.0 m. The lithologic features of the coal seam, roof, and floor are listed in Table 1.

3 Numerical simulations and rock mechanics tests

3.1 Numerical model

In this study, the FLAC3D 5.0 (Fast Lagrangian Analysis of Continua in Three Dimensions; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc., USA) numerical modeling software for geotechnical analyses of soil, rock, groundwater, constructs, and ground support was used to develop numerical models with coal-seam dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° and study the stress distribution and rock-mass failure features of the SDCS. This software is known to simulate accurately the mechanical characteristics of the failure and plastic flow of coal and rock materials reaching their strength limit or yield-stress levels in geotechnical and mining engineering applications, as well as predicting their deformation, progressive failure, and instability behavior (Kumar et al. 2017; Peng 2007).

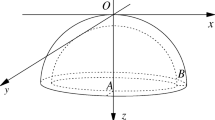

The dimensions of the numerical model (X × Y × Z) were 180 m × 300 m × 400 m, and the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion was applied in the numerical simulation. Vertical displacement was restricted at the bottom of the model, while horizontal displacement was restricted at the four sides of the model. The top of the model corresponded to the stress boundary. The burial depth of the coal seam was taken as 440 m, and the stress applied to the upper part of the model was 7.5 MPa. The thickness and average density of the rock layer above the model were 300 m and 2500 kg/m3, respectively. The effect of this rock layer on the upper part of the model was reduced to a vertical stress of 300 × 0.025 = 7.5 MPa. The three coal seams with different dip angles had the same engineering and geological conditions. Rocks collected from rock-fidelity cores taken on site were processed in the laboratory into standard rock samples meeting the requirements of the International Association of Rock Mechanics. Eventually, the physical and mechanical parameters of the rock samples were obtained through uniaxial compression and shear tests and are summarized in Table 2. The numerical model of the coal seam with a dip angle of 45° is shown in Fig. 1.

3.2 Rock mechanics and compression tests

The surrounding rock was damaged after the SDCS was excavated, leading to stress redistribution in the former. This resulted in deformation, breaking, and slip of the overlying strata. Compression tests were performed on precracked standard rock samples with dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° to analyze the stress-induced fracture process of the rock mass, after which the damage of the rock mass after SDCS excavation was analyzed qualitatively. The dip angle of the prefabricated cracks was defined as the included angle between the crack and the sample cross section. The rock samples used for the tests were collected from the fine sandstone layer of the main roof in the working face. To ensure reliable experimental results, the rock samples were subjected to P-wave tests using an ultrasonic system (Sonic Viewer-SX; Oyo Corp., Japan); samples with highly disperse wave velocities were excluded, and only those with similar wave velocities were selected for mechanical testing. The rock samples were subjected to pre-cracking using a diamond disc cutting machine, with the cracks being 60 mm long, 3 mm wide, and 20 mm deep, as shown in Fig. 2. The experimental setup comprised a loading control system, an acoustic emission (AE) monitoring system, a digital monitoring system, and a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) monitoring system, as shown in Fig. 3. The first three systems were used simultaneously during the tests to facilitate the subsequent data processing, while the SEM monitoring system was used after the tests to scan the macroscopic fracture surfaces of the intact and pre-cracked rock samples and to assess the microscopic damage features.

The loading control system comprised a multifunction automatic rigid rock material testing servo machine (RMT-150B; Institute of Rock and Soil Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) that could realize conventional uniaxial and triaxial compression test modes, along with automated data collection, processing, and construction and display of the stress–strain curve. The load was increased at a rate of 0.5 kN/s until the rock sample finally fractured.

The AE monitoring system comprised a multi-channel full-wave AE signal analyzer (DS5-16B; Beijing Softland Times Scientific & Technology Co., Ltd., China) that could extract characteristic parameters such as the AE energy and ring-down count. Four AE transducers were attached to each rock sample using a coupling agent. Before the tests, the system was calibrated several times to adjust its accuracy, and the final presets were an AE-transducer resonance frequency of 100–600 kHz, a sampling rate of 3 MHz, a preamplifier gain of 40 dB, and a monitoring threshold of 35 dB.

The SEM examinations were performed using a scanning electron microscope (FlexSEM1000; Hitachi, Japan) that could achieve a magnification of 60–300 times and an accelerating voltage of 0.3–20 kV with a resolution of 4 nm. The digital monitoring system was equipped with a camera (AF-P; Nikon, Japan) to capture the fracture morphology during loading.

4 Breaking and instability features of overlying strata during SDCS mining

After excavating the SDCS, the previously intact structure of the overlying strata was damaged, and the morphology of the damaged zone varied with the seam dip angle. As shown in Fig. 4, the upper part of the working face had a ladder-shaped plastic damage zone. The upper rock mass was intact along the ladder-shaped damage line (the white line in Fig. 4), and there was no macroscopic damage present as mining-induced cracks. The lower part of the working face had an upright plastic damage zone. With increasing dip angle of the coal seam, the plastic damage zone in the overlying strata became more hump-like and migrated toward the lower part of the working face. Also, the shear and plastic damage in the overlying strata became more severe, although the plastic damage zone in the overlying strata narrowed in overall scope.

5 Stress evolution law of overlying strata during SDCS mining

5.1 Stress distribution law of overlying strata during SDCS mining

After excavating the coal seam, the overlying strata underwent breaking, rotation, and slip under the action of in situ and tectonic stresses. Stress redistribution occurred in the surrounding rock of the working face, and the distribution morphology and magnitude of the vertical stress were used to evaluate the degree of compressive failure of the overlying strata.

As shown in Fig. 5, for each of the studied dip angles (30°, 45°, and 60°), the overlying strata had an apparent arch-shaped stress release zone whose height decreased and whose top migrated toward the tailentry in the working face with increasing dip angle. At a dip angle of 30°, the vertical stress release within the arch was more significant. A vertical stress concentration zone formed in the upper and lower roadways (arch feet on both sides). The scope and degree of vertical stress concentration in the lower part of the working face (lower arch foot) were wider and higher than those in the upper part (upper arch foot). With increasing dip angle, the scope and degree of vertical stress concentration in the upper part of the working face (upper arch foot) decreased. However, the scope of vertical stress concentration in the lower part of the working face (lower arch foot) increased, while the degree of vertical stress concentration dropped.

Selected were three vertical stress states (T1–T3) that occurred during excavation of coal seams with dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°, respectively. By studying the evolution of the vertical stress state during excavation, the start points of stress release and the pathways of stress transfer in the overlying strata were identified. As shown in Fig. 6, in state T1, the start point of stress release in the overlying strata migrated toward the lower part of the working face along with an increase in dip angle (the black box in Fig. 6). From T1 to T3, the stress release arch in the overlying strata migrated gradually from the lower part of the working face to the upper one, accompanied by a gradual increase in arch height. From T1 to T3, the average variation rates of vertical stress in the overlying strata at dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° were 0.4 × 107, 0.3 × 107, and 0.2 × 107 Pa (or 4, 3, and 2 MPa), respectively. The average variation rate of vertical stress decreased with increasing dip angle.

5.2 Stress distribution law during mining of SDCS

With increasing dip angle, the component of the acceleration due to gravity normal to the overlying strata dropped, while the tangential component rose. After excavation of the SDCS, the overlying strata exhibited a more pronounced trend of shear and slip. Therefore, it was necessary to analyze the shear stress in the overlying strata of the SDCS. Also, the maximum shear stress was one of the most useful indicators of the trend and position of shear failure.

As shown in Fig. 7, the overlying strata had an apparent arch-shaped shear zone (shear stress arch) for each of the studied dip angles (30°, 45°, and 60°). With increasing dip angle, the arch height decreased and the shear stress within the arch increased. The shear trend of the overlying strata became more conspicuous with increasing dip angle. A shear stress concentration zone formed at the arch feet on both sides of the working face (the green block in Fig. 7). The scope and degree of shear stress concentration were wider and higher at the upper arch foot than those at the lower arch foot. With increasing dip angle, the scope of shear stress concentration at the upper arch foot decreased while the degree of shear stress concentration increased. At the lower arch foot, both the scope and degree of shear stress concentration dropped.

During excavation, three maximum shear stress states (T1–T3) were selected for the coal seams with dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°, respectively. Studying the shear stress evolution process (different shear stress states during the excavation) was an effective way to analyze the features of the stress arch during excavation of the coal seam.

As shown in Fig. 8, from T1 to T3, the height of the shear stress arch in the overlying strata rose gradually with increasing dip angle. During this process, the shear stress concentration zone (the red box in Fig. 8) in the arch top migrated to the arch feet on both sides. In particular, the migration of the shear stress concentration zone in the arch top toward the upper arch foot became more intense, while that toward the lower arch foot became smoother. The shear stress concentration zone in the arch top at stage T1 at dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° was found in the middle-upper, middle-lower, and upper parts of the working face, respectively. The scope of shear stress concentration narrowed with increasing dip angle. From T1 to T3, the average variation rates of maximum shear stress in the overlying strata at dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° were 0.4 × 107, 0.3 × 107, and 0.2 × 107 Pa (or 4, 3, and 2 MPa), respectively. The average variation rate of maximum shear stress increased with increasing dip angle.

6 Mechanical features of precracked rock samples with different dip angles

The synergistic response of the stress–strain curve and AE parameters were then considered. On this basis, the macroscopic failure morphology of the rock samples and SEM features of the fractured site were characterized. The mechanical response mechanism of the precracked rock samples with dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60° was analyzed.

As shown in Fig. 9, the axial stress needed for the precracked rock samples to fail dropped with increasing dip angle. The precracked rock samples with a dip angle of 60° were the most susceptible to failure. With increasing dip angle, the failure features of the rock samples changed from tensile-and-splitting failure to shear-and-slip fracture. The frictional faulting and shear-and-slip features of the fracture surface intensified with increasing dip angle (see the yellow block in Fig. 9). The number of newly formed macroscopic shear cracks rose with increasing dip angle. The first macroscopic crack (first peaks of AE energy and ring-down count) occurred earlier, and the axial stress needed for failure increased with increasing dip angle. Moreover, the number of elastic waves emitted upon failure of the rock samples increased with increasing dip angle. More elastic energy stored in the rock samples was released via macrocracks and weak positions on the sample surface, leading to crack-induced AEs. There was a sudden increase in the AE energy and ring-down counts, which indicated a burst-type emission.

7 Field tests and monitoring

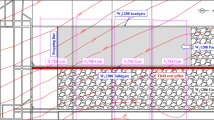

The 1212 (3) working face of the Panbei Coal Mine had an inclination length of 120 m, a coal seam thickness of 4 m, an average inclination angle of 40°, and adopted a 3/8 working system, advancing 5 m per day. Fully mechanized longwall mining was realized, with 60 four-pillar chock-shield supports installed in the working face. Three support pressure-measuring regions were arranged along the dip direction of the working face. They were located in the lower (support 15), middle (support 34), and upper (support 51) parts of the working face, respectively. The aforementioned 60 supports were installed via a digital pressure dynamic monitoring system (KJ216; Uroica, China) that integrated computer monitoring, data communication, and sensor technologies to realize real-time monitoring, transmission, and preservation of the working resistance of the supports as the working face advanced. The specific monitoring process is shown in Fig. 10, and the field monitoring results that were obtained are shown in Fig. 11. As the working face advanced, the support loads in the lower part of the working face along the dip direction were the largest: their maximum and average values were 2774 and 2634 kN, respectively. The maximum and average support loads in the middle part of the working face were smaller by 22% (2153 kN) and 28% (1877 kN), respectively, than those in the lower part. The support loads in the upper part of the working face were the smallest: their maximum and average values were 1051 and 652 kN, respectively, being lower by 62% and 76% than those in the lower part.

8 Discussion

The breaking and stress distribution of the overlying strata in the SDCS displayed asymmetric features. During excavation of the coal seam, the shear stress concentration zone in the overlying strata migrated toward the upper part of the working face at an accelerating rate. The scope of vertical stress release in the upper part of the working face expanded, and the shear failure became more intense. The active region in which the overlying strata broke under excavation migrated upward along the dip direction of the working face. With increasing dip angle, caving gangue slipped downward along the working face. Meanwhile, the heterogeneous filling features of the gangue intensified progressively. The broken overlying strata in the lower part of the working face reduced the displacement space range in the goaf. The constraints imposed by the gangue on the overlying strata became more significant, and the degree of vertical stress concentration increased, in contrast to shear stress concentration. The caving rock mass exhibited higher integrity, and the caving bodies acted directly on the gangue (or support beams). The similar physical simulation study revealed that (i) the appearance of free space in the upper part of the working face, (ii) the presence of a macroscopic fracture section in the overlying strata, and (iii) a loss of bearing capacity in the rock below the fracture section. However, a stable cantilever beam structure formed above the fracture section (box A–A in Fig. 12), which had a certain bearing capacity. The accumulation of gangue in the lower part of the working face reduced the room available for displacement of the overlying strata in the goaf. The overlying strata contained transverse and longitudinal cracks but were not separated completely from the stable strata and instead existed in the form of a hinged rock beam structure (box B–B in Fig. 12). After the overlying strata broke along the dip direction, a hinged rock beam formed above the margin of the goaf lower part. This implied an increase in the working resistance of the supports in the lower part of the working face, which exceeded that in the upper part along the dip direction.

Along with excavation of the coal seam, vertical stress release occurred in the lower part of the overlying strata, where the rock mass was the first to fail. At this moment, there was no gangue to fill the lower part of the working face, resulting in upright plastic failure. The damaged zone in the overlying strata migrated upward along the dip direction of the working face. Gangue then slipped and filled the lower part of the working face. As the rock mass overlying the working face lost its support from the gangue. Consequently, the caving structure of the overlying strata was asymmetric, as shown in Fig. 13

At smaller dip angles, the prefabricated cracks in the rock samples (original small structures) had sufficient time to evolve and develop during the loading process. Therefore, the first peak of AE energy and ring-down counts occurred later, and the scope of vertical stress release in the overlying strata expanded. The overlying strata displayed progressive failure features. At larger dip angles, a large amount of elastic energy stored around the prefabricated cracks in the rock samples was released. As a result, the local solid load-bearing structure was likely to undergo instantaneous failure. Upon failure, there was a sudden increase in AE energy and the number of ring-down counts. The shear-and-slip failures of the rock samples became more pronounced. The variation rate of shear stress in the overlying strata increased, and the overlying strata failed suddenly.

9 Conclusions

The following conclusions are drawn from the results obtained in this study.

(1) Shear stresses in the overlying strata of the SDCS were inversely proportional to vertical stresses. The degree of shear stress concentration in the overlying strata increased with increasing dip angle. Meanwhile, the height of the vertical stress release arch decreased, and the overlying strata experienced a transition from tensile failure to shear-and-slip failure. The heterogeneous filling features of the gangue meant that the overlying strata structure was asymmetric.

(2) The lower part of the overlying strata was the first to break, accompanied by vertical stress release. The damaged zone in the overlying strata migrated upward along the dip direction of the working face under the excavation. Because of high shear stress and dip angle effects, the upper part of the overlying strata broke, slipped, and filled the lower part of the working face. As a result, the failure rate of the lower part of the overlying strata dropped. The vertical stress in this part increased, while the shear stress decreased.

(3) At small dip angles, the overlying strata underwent failure and instability under the action of compressive stresses. With the development of the prefabricated cracks in the rock samples, the failure depth of the overlying strata increased, and the overlying strata underwent progressive failure. With increasing dip angle of the coal seam, the breaking of the overlying strata was no longer driven by compressive stresses but became controlled by shear ones, while the overlying strata failed suddenly.

References

Chi XL, Yang K, Fu Q (2019) Analysis of regenerated roof and instability support control countermeasures in a steeply dipping working face. Energy Explor Exploit 38:1082–1098

Chi XL, Yang K, Fu Q, Dou LT (2020) The mechanism of mining-induced stress evolution and ground pressure control at irregular working faces in inclined seams. Geotech Geol Eng 38:91–107

Das AJ, Mandal PK, Bhattacharjee R, Tiwari S, Kushwaha A, Roy LB (2017) Evaluation of stability of underground workings for exploitation of an inclined coal seam by the ubiquitous joint model. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 93:101–114

Deng YH, Wang SQ (2014) Feasibility analysis of gob-side entry retaining on a working face in a steep coal seam. Int J Min Sci Technol 24:499–503

Gao MZ (2004) Similarity model test of strata movement with steep seam. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 23:441–445

Hu SX, Ma LQ, Guo JS, Yang PJ (2018) Support-surrounding rock relationship and top-coal movement laws in large dip angle fully-mechanized caving face. Int J Min Sci Technol 28:533–539

Kulakov VN (1995) Stress state in the face region of a steep coal bed. J Min Sci 31:161–168

Kumar A, Kumar R, Singh AK, Ram S, Singh PK, Singh R (2017) Numerical modelling-based pillar strength estimation for an increased height of extraction. Arab J Geosci 10:411

Liu J, Wang HJ, Li YC, Geng X (2015) The migration law of overlay rock and coal in deeply inclined coal seam with fully mechanized top coal caving. J Environ Biol 36:821–827

Lv WY, Wu YP, Ming L, Yin JH (2019) Migration law of the roof of a composited backfilling longwall face in a steeply dipping coal seam. Minerals 9:188

Peng SS (2006) Longwall mining. Department of Mining Engineering, West Virginia University, Morgantown

Peng WB (2007) FLAC3D practical tutorial. Mechanical Industry Press, Beijing, pp 1–3

Tu HS, Tu SB, Yuan Y, Wang FT, Bai QS (2015) Present situation of fully mechanized mining technology for steeply inclined coal seams in China. Arab J Geosci 8:4485–4494

Tu HS, Tu SH, Zhang C, Zhang L, Zhang XG (2017) Characteristics of the roof behaviors and mine pressure manifestations during the mining of steep coal seam. Arch Min Sci 62:871–891

Wang JN, Jiao JL (2016) Criteria of support stability in mining of steeply inclined thick coal seam. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 82:22–35

Wang JA, Zhang JW, Gao XM, Wen JD, Gu YZ (2015) Fracture mode and evolution of main roof stratum above longwall fully mechanized top coal caving in steeply inclined thick coal seam (I)—initial fracture. J Chin Coal Soc 40:353–1360

Wang B, Dang F, Chao W, Miao Y, Li J, Chen F (2019) Surrounding rock deformation and stress evolution in pre-driven longwall recovery rooms at the end of mining stage. International Journal of Coal Science & Technology 6(4):536-546

Wang J, Wei W, Zhang J (2020) Theoretical description of drawing body shape in an inclined seam with longwall top coal caving mining. Int J Coal Sci Technol 7(1):182–195

Wu YP, Yun DF (1999) The stability control of support at top caving face with steep seam. Ground Press Strata Control 16:82–85

Wu YP, Xie PS, Ren SG (2010) Analysis of asymmetric structure around coal face of steeply dipping seam mining. J Chin Coal Soc 35:182–184

Wu YP, Liu KZ, Yun DF, Jie PD, Wang GW (2014) Research progress on the safe and efficient mining technology of steeply dipping seam. J Chin Coal Soc 39:1611–1618

Wu YP, Yun DF, Xie PS, Fan ZD, Wang DF, Zhang YH (2020) Progress, practice and scientific issues in steeply dipping coal seams fully-mechanized mining. J Chin Coal Soc 45:24–34

Xie PS, Tian SQ, Duan JJ (2019) Experimental study on the movement law of roof in pitching oblique mining area of steeply dipping seam. J Chin Coal Soc 44:2974–2982

Yang K, Kong XY, Lu W, Liu S (2015a) Study of strata pressure behaviors with longwall mining in large inclination and thick coal seam under closed distance mined gob. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 34:4278–4285

Yang K, Lu W, Pan GR, Sun L (2015b) Investigation into strata behaviours and ground control of high height rotary longwall mining in large inclined angle coal seam under complicated geological conditions. J Min Safety Eng 32:199–205

Yang K, Chi XL, Liu S (2018) Instability mechanism and control of hydraulic support in fully mechanized longwall mining with large dip. J Chin Coal Soc 43:1821–1828

Yin GZ, Li XS, Guo WB (2010) Photo-elastic experimental and field measurement study of ground pressure of surrounding rock of large dip angle working coal face. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 29:3336–3343

Yun DF, Liu Z, Cheng WD, Fan ZD, Wang DF, Zhang YH (2017) Monitoring strata behavior due to multi-slicing top coal caving longwall mining in steeply dipping extra thick coal seam. Int J Min Sci Technol 27:179–184

Zhang B, Cao SG (2015) Study on first caving fracture mechanism of overlying roof rock in steep thick coal seam. Int J Min Sci Technol 25:133–138

Zhang YD, Cheng JY, Wang XX, Feng ZJ, Ji M (2010) Thin plate model analysis on roof break of up-dip or down-dip mining stope. J Min Safety Eng 27:487–493

Zuo JP, Wang JT, Jiang YQ (2020) Macro/meso failure behavior of surrounding rock in deep roadway and its control technology. Int J Coal Sci Technol. 6(3):301–319

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51634007) and the Graduate Innovation Fund Project of Anhui University of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2019CX1003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, X., Yang, K. & Wei, Z. Breaking and mining-induced stress evolution of overlying strata in the working face of a steeply dipping coal seam. Int J Coal Sci Technol 8, 614–625 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-020-00392-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-020-00392-3