Abstract

Scholars have long feared that regional economic specialization, fostered by freer trade, would make the European Union vulnerable to economic downturn. The most acute concerns have been over the adoption of the common currency: by adopting the euro, countries renounce their ability to meet an asymmetric shock with independent revaluations of their currencies. We systematically test the prediction that regional specialization increases vulnerability to economic downturn using a novel dataset that covers all of the EU’s subnational regions and major sectors of the economy between 2000 and 2013. We find that, contrary to conventional wisdom, the most specialized regions actually fared better during the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Specialized regions performed worse only in states that remained outside the Eurozone. The heightened vulnerability of non-Eurozone states cannot be attributed to fiscal or social policy failures. Rather, our results suggest the common currency may have helped Eurozone members share risk. This bodes well for the resiliency of the EU, even as it navigates another economic downturn from the asymmetric impact of the novel coronavirus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Even before the COVID-19 crisis and the rancorous negotiations for an EU-wide relief package, it was clear that the European project—the goal of an “ever closer union”—was facing trouble. Brexit, the recurrent southern debt crises, a chain of banking insolvencies, the imperiled Euro, and increasing support for anti-European Union political parties have raised questions about whether the European project’s design is fundamentally flawed.

In its briefest form, the case for the prosecution runs as follows. From its inception, the European Union (EU) has taken as fundamental the principle of free trade in goods, services, and factors of production (labor and capital) among its member states. As in any system of free trade, but especially in one that trades so intensively as the EU, governments fear competitive devaluations of other states’ currencies. This is a notoriously simple but highly effective form of import protection and export promotion. In the view of the states that had repeatedly fallen victim to competitive devaluations (chief among them Germany), efforts to obviate that threat through semi-fixed exchange rates had repeatedly failed. The only ironclad commitment against competitive devaluations was the adoption of a common currency (cf. Frieden 2015, p. 150). But, as we know from the theory of optimum currency areas (OCAs), separate states can sustain a common currency only to the extent that they experience symmetric business-cycle shocks, i.e., slump and boom together, or can compensate asymmetric shocks through automatic transfers. Hence, the whole project of European unification could easily collapse from the pressures of asymmetric shocks, unless Brussels received the mandate and means to transfer resources from the booming to the stricken economies. A lot hinges on Europe’s immunity, or at least resilience, to asymmetric economic shocks.

Yet the very success of economic integration may paradoxically have made Europe more vulnerable to such dislocations. Almost three decades ago, Krugman (1991) speculated that dismantling the remaining barriers to trade within the EU would lead to increased agglomeration of production and greater dissimilarity of member-state production profiles. As Krugman put it, perhaps “eventually Europe will look like America, with a similar degree of localization and specialization,” i.e., concentration of specific sectors in a few places (ibid., p. 79). More presciently, he also conjectured that such specialization, precisely by exposing different regions and countries to greater risk of asymmetric shocks, might well make the EU even less of an optimal currency area and endanger the project of monetary union that had then been set in train.

Whether greater regional specialization entails greater asymmetry in business cycles has, of course, been hotly debated. Examining twenty countries’ bilateral trade and business cycles over thirty years, Frankel and Rose (1998) found that greater intensity of trade led to more symmetric business cycles. Willett et al. (2010) find that this relationship holds after the adoption of the euro in 1999, by comparing business cycle correlations in the decade before euro adoption (1980-1990) and the years immediately following adoption (1999-2005). On the other hand Kalemli-Ozcan et al. (2001) found, among OECD countries and US states, that greater specialization was indeed associated with more asymmetric business cycles. Underscoring the limitations of their findings, they concluded that “which effect will dominate in the European Monetary Union remains an open empirical question” (Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2001, pp. 110).

We address exactly this empirical question, considering the consequences of regional specialization—both between and within countries—during an economic downturn. The global financial crisis of 2008-09 constitutes an important test of European integration because it highlights susceptibility to a regionally-asymmetric shock. As the worst slump in aggregate demand, and hence the steepest decline in many industries’ production, since the 1930s, the global financial crisis should have revealed any disparities in regions’ differential vulnerability.Footnote 1 Leveraging newly-released data from Eurostat and a constellation of national data sources, we address empirical questions about specialization and asymmetry. Specifically, we ask at the level of Eurostat’s 266 NUTS-2 regions, two questions: (a) Were Europe’s most specialized regions hit hardest in the crisis? And (b) did membership in the Eurozone magnify the ill-effects of the crisis?

Our answers are, in both cases, no. (a) Europe’s most specialized regions were not, in fact, hit hardest by the 2008-09 economic shock. The EU’s regions displayed steady levels of specialization between 2002 and 2008, the years immediately preceding the crisis.Footnote 2 By the point the crisis hit, the extent of specialization was a given. In more than half of EU states, the most specialized regions actually experienced a less severe decline in economic activity than their more diversified counterparts. In only six of the member states was greater regional specialization associated with a more severe downturn; all six countries are outside the Eurozone.Footnote 3 (b) Eurozone membership was actually associated with less severe economic contractions in the wake of the global financial crisis. Krugman’s fears about asymmetric shocks destabilizing the EU, informed by OCA theory, Footnote 4 simply do not bear out, at least in the short-term. Instead, our findings suggest that Frankel and Rose were correct: a common currency pools risk amongst its members, insuring those areas most susceptible to economic downturn.

The implications are significant. Whether the EU is a stable arrangement is a crucial and timely question, particularly given the asymmetric fallout from COVID-19. Our findings point toward a positive answer and, more broadly, suggest that this form of deep interstate cooperation can be quite resilient to sudden economic shocks. The crisis of 2008-09 dealt the least severe blow to Europe’s most specialized regions. This clear finding lends some confidence that freer trade is making Europe less, not more, susceptible to asymmetric shocks. If, instead, the crisis had impacted regions asymmetrically, it would be bad news indeed. Had specialization necessarily rendered regions more vulnerable, an asymmetric downturn would pose a profound political challenge both for the EU and for the governments of member states. One political solution would then have been to slow or reverse specialization, e.g., through a more aggressive use of European regional development funds to promote diversification of less developed regions and dispersal of otherwise regionally concentrated high-tech sectors. That would however, as economists have long recognized, come with a cost to economic growth in the EU as a whole, since regionally concentrated industries are usually more efficient (Ciccone 2002). Our results indicate that these concessions are fortunately unwarranted. Deep economic integration, and the regional specialization it fosters, appears more sustainable than Krugman (1991) and others predicted.

1 Economic integration in the European Union

Scholars and architects of the European Union alike foresaw significant risks from deep economic integration and, in particular, a shared currency. The concern was that an economic downturn would hit asymmetrically, affecting countries differently and, worse still, delivering uneven punches to different regions within countries. Asymmetric shocks are concerning because Europe faces the simultaneous need for, but problematic possibility of, sustaining an optimum currency area. Asymmetric shocks would lead governments to disagree amongst themselves over the appropriate form and scope of an EU response: some might advocate an aggressive and others a modest collective response, each with the potential to stoke nationalist sentiments within countries (e.g., Bechtel et al. 2014). At the same time, those governments would be under tremendous pressure to decide which geographical regions, industries, or sectors within their domestic purview should receive assistance.

This concern grew out of a fundamental quandary in the project of European unification. Central to the economic integration of Europe, countries elected to remove all barriers to trade among them. By allowing free movement of goods across borders, states could ostensibly reap the benefits of specialization and boost economic growth. There is strong evidence that national specialization of production profiles grew markedly between 1968 and 1990 (Amiti 1998). Regional specialization within countries also increased in tandem with the “free-ness” of trade within the bloc during the 1990s (Brakman et al. 2006). Yet trade could not become fully free, nor its full efficiency gains achieved, so long as European governments maintained independent currencies—or so it was widely believed. Governments that maintained their own currencies would always be tempted, particularly in a downturn or before an impending election, to boost exports and stimulate their economies through timely devaluations. Currency manipulation would have similar effects as might have been achieved by the production subsidies that the EU treaties clearly forbade. The brief and ill-fated experiment of a supposedly irrevocable peg, the Exchange Rate Mechanism, had amply confirmed these fears (Obstfeld 1996). In adopting the euro, the EU aimed to deepen and stabilize the internal market, removing the risk that member states would engage in competitive devaluation to gain market advantage.

Countries gain from a shared currency, according to the theory of optimum currency areas (OCAs), to the extent that they trade with one another, but lose to the extent that their business cycles are uncorrelated—i.e., that they experience “asymmetric economic shocks.” Clearly, asymmetric shocks are crucial for understanding the political feasibility of monetary unions. We highlight the most commonly recognized threat to asymmetric shocks in currency unions: specialization. In what has become the conventional wisdom, Krugman (1991) argued that deeper economic integration would increase regional specialization—both between countries and between local labor markets within countries—which would expose regions to a greater risk of asymmetric shocks due to industry-specific downturns.

When most specialization occurs between countries, asymmetric shocks will fracture interests among them. We would expect this when member states significantly differ in factor endowments, which induces factor-based trade and therefore country-level specialization. If, however, member countries share similar factor endowments, then most trade will be intra-industry with specialization patterns developing between local labor markets within countries. For example, each member country develops its own manufacturing hub and its own agricultural regions to satisfy consumer love of variety. Italy will export to the rest of Europe cars manufactured in the Emilia-Romagna region and wines from the hills of Tuscany and Abruzzo, while at the same time importing German cars from Munich and French wine from Bourdeaux. Consistent with this, most countries exhibit significant variation in specialization between subnational regions, which drives geographic heterogeneity in economic outcomes such as unemployment, real wages, productivity, and innovation (Enrico 2011; Autor et al. 2016). To the extent that this type of specialization dominates a monetary union, asymmetric shocks will likely develop within members rather than between them.

Asymmetric shocks within member states pose a significant threat to monetary unions. Asymmetries between local labor markets fracture domestic support for monetary integration along geographic lines. In the event of an economic crisis, more exposed specialized local labor markets will favor a more aggressive monetary policy than more diversified labor markets in the same country would prefer. This variant of asymmetric shocks can therefore tear apart member states from within. Consequently, the politics of monetary integration would look similar to the domestic politics of trade and immigration, emphasizing how anti-globalization sentiment reflects specialization patterns between local labor markets (Colantone and Stanig 2018a, b; Georgiadou et al. 2018).

In reality, specialization varies both within and between countries. This produces the potential for asymmetric shocks to split monetary coalitions into country-groups and local labor market groups. In recognition of the potential importance of subnational regions in interstate politics, our analysis asks how specialization between European labor markets contributes to asymmetric shocks within and between countries.

This leads us to our first empirical expectation: the more specialized a member state’s regions, the more exposed it will be to an economic shock and the worse will be its subsequent economic performance. In other words, the financial crisis exposed the European Union to asymmetric shocks among member states and within them. Our analysis section describes in detail how a regional unit of analysis can be used to measure both types of asymmetry.

The alternative hypothesis is that specialization does not induce asymmetric shocks. That is, specialized regions fare no worse than their less-specialized counterparts (or even fare better). We might expect this for three reasons: (i) sufficient, and ideally automatic, fiscal transfers; (ii) ample labor mobility between regions and countries; or (iii) a pooling of risk among members.

First, fiscal transfers allow members to maintain symmetric business cycles by injecting stimulus into the areas experiencing the largest contractions. Economists have long warned that in the absence of a fiscal union—common taxation and policies to absorb regional disturbances—Europe would be on thin ice (Eichengreen 1990; Sala-i Martin and Sachs 1991; Bayoumi and Masson 1995). Brussels, whose revenues are less than 2 per cent of EU GDP, simply lacks the means to carry out significant interregional transfers. This is abundantly clear in the amounts allocated in the EU Cohesion fund, which aims to reduce disparities between member states by distributing funds to members whose gross national income is below 90 percent of the EU average. During the 2008-09 global financial crisis, the fund allocated approximately 57.8 billion euros, which amounts to just 0.036 per cent of the 1.6 trillion euros lost during the same time period.Footnote 5 More than a decade after the global financial crisis, there is hope for a deeper fiscal union with the July 2020 agreement for a 750 billion euro rescue package to help depressed areas hit hard by the novel coronavirus. But with only 390 billion taking the form of grants due to intransigence of the so-called “Frugal Four”—Austria, Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden—uncertainty remains for a systemic overhaul of EU-wide fiscal policy.

Second, if fiscal transfers are lacking, the relocation of labor from low growth to high growth countries may allow for more symmetric business cycles. However, significant labor market frictions in the EU limit worker migration, thereby allowing differences in growth and unemployment to persist. Language barriers in the EU represent one such friction. Indeed, a survey among European labor market experts found that the single European labor market had not reached its potential due to these language barriers, but also due to the lack of EU harmonization of professional qualifications and social security systems (Krause et al. 2017). Comparative studies of labor mobility in the US and EU consistently show less mobility within the EU, although this gap narrows with the EU enlargement (Decressin et al. 1994; Bentivogli and Pagano 1999). There is little evidence of wage convergence between countries in the EU (Naz et al. 2017). Most important to our paper, Arpaia et al. (2016) and Jauer et al. (2019), and Basso et al. (2018) confirm that labor mobility in the EU is not high enough to absorb an economic downturn fully. The best estimates suggest that migration absorbed about one-quarter of the 2008-09 shock within a year. However, the results are driven largely by migration of recent EU accession country citizens.

With limited fiscal transfers and insufficient migration to stymie asymmetric shocks, we might still expect specialized regions to fare no worse than their less-specialized counterparts due to risk sharing—either public or private—amongst regions. Risks are shared publicly—and so far within states, not among them—by automatic fiscal transfers, deposit insurance, and implicit guarantees. Risks are shared privately—both within and among states—through portfolio adjustments—e.g. by major banks and institutional investors that hedge against any regionally-specific shock—as well as through inter-regional trade, where external demand replaces the depressed local demand (Schelkle 2017). We contend that this private risk-sharing among member states substitutes for the absence of fiscal transfers (i.e., public risk-sharing) and labor mobility during a crisis. As Frankel and Rose (1998) suggested, OCAs may indeed be “endogenous.” That is, as regional trade and specialization increase, so does risk-sharing, and with it, symmetric business cycles.

As the financial crisis spread from its origins in the United States, few people anticipated how rapidly and comprehensively it would permeate Europe’s economy. By the end of 2009, real GDP across Europe dropped by four per cent, the sharpest contraction in its history and the deepest recession since the 1930’s (European Commission 2009). It displayed exactly the features that critics of the Eurozone feared. First, the crisis was unforeseen and sudden: it was, unlike the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, a predominantly exogenous shock.Footnote 6 Following the US stock market plunge, the downturn rapidly spread through Europe’s financial sector and then the economy at large, precipitating a significant downturn in production. Second, the shock had a varied effect across regions in the EU, as well as sectors within the economy. Third, the downturn was too severe for the member states to mobilize a rapid coordinated response. Indeed the insufficiency of a coordinated response became evident in the following years. EU bureaucracy undertook greater economic policy surveillance and supervision of the financial sector (e.g., Hodson 2011;Bauer and Becker 2014) but the scale of reforms was limited. Moreover, the European Central Bank, with pressure from the conservative Bundesbank, was reluctant to engage in the unorthodox monetary policies that buoyed economies abroad. Thus the suddenness, asymmetry, and intractability of the financial crisis were precisely the perfect storm that risked unraveling the economic and monetary union.

This leads to our second empirical expectation: If the Eurozone heightened member states’ vulnerability to asymmetric shocks, then, all else equal, Eurozone membership should be associated with an especially severe contraction in production following a shock. Conversely, if members of the Eurozone fared equally well or better than their non-Eurozone counterparts, then it suggests a two-tiered system is a durable arrangement. We now turn to explaining the data we employ to analyze our two empirical expectations.

2 Data and empirical model

To assess the European Union’s vulnerability to asymmetric economic shocks, we assembled an extensive data set. Our main dependent variable is the economic performance—measured as the one-year change in gross value added (GVA)—from each sub-national region within the EU between 2000 and 2013: \(\varDelta \log (\text {GVA})_{t\text { to }t+1}\).Footnote 7 Sub-national regions are measured at the NUTS-2 level reported by Eurostat, and we distinguish among seven sectors of production. Here, as in calculating the other variables, we separated or combined industries in order to merge across data sources and fill in more complete data from national sources. Some member states joined the EU after our sample commences; for these countries, the first year of observation is the year of admission.Footnote 8 Thus our underlying data set consists of an imbalanced panel covering 19 countries,Footnote 9 266 regions, and seven sectors for each year from 2000 (or year of accession) through 2013, for a total of 23,156 observations. See the Appendix for details.

The global financial crisis was felt across the EU unevenly. Figure 1 displays the economic performance for each region. It is measured as the annual percent change in GVA from 2008 to 2009 and illustrates the geographical variation in the crisis across the EU at the level of NUTS-2 regions. Some regions, especially in the EU periphery, experienced drastic contractions in their local economies, up to 23 per cent while others weathered the crisis relatively unscathed. Six regions experienced minute growth during this period.Footnote 10 Likewise, there was a significant range in country-wide contractions. For instance, France’s country-wide decline in GVA was approximately 2.8 percent while the UK suffered dramatically in that same time frame with a 14.5 per cent contraction. Clearly, the financial crisis had major negative repercussions for some countries’ overall economies but not others. Despite significant cross-national and cross-regional discrepancies, the time trends in GVA for regions in the most and least specialized countries are strikingly similar in the pre-crisis period.

We select this time-frame to focus on the short–run repercussions of the 2008-09 crisis. We do so for good reason. The 2008 to 2009 period brought a distinctly severe contraction in GVA across the vast majority of EU regions, as shown in Fig. 2. Production in the EU fell by nearly 4.5%, the most severe decline in the history of the institution. There was a slight rebound in the ensuing year and then an approximate return to previous growth rates.

We end our sample with the 2012–2013 change in GVA, but also examine abbreviated samples to ensure we are not confounding the financial crisis with the sovereign debt crisis, a related but distinct economic event that subsequently shook the EU. Figure 2 clearly demonstrates that the the 2012–2013 change in GVA was similar to trends in the immediate years preceding the crisis. This dispels concern that our analysis is confounded by a second downturn from the sovereign debt crisis; the 2008-09 shock was uniquely severe.

Our goal is to test whether specialized regions were more susceptible to an EU-wide economic shock than their more diversified counterparts. We define an asymmetric economic shock by the interaction between regional specialization and the sudden 2008 economic shock. The two constituent parts of the interaction term represent the degree of asymmetry, measured as the extent to which regions are economically specialized (typically in different sectors), and the shock, which occurred suddenly and at approximately the same time for each region. To the extent that some regions were quite specialized and others were not, they would be expected to be asymmetrically vulnerable to the shock.

The first component of the interaction term and our most salient explanatory variable, specialization, measures inter-sectoral heterogeneity within each region. We derive specialization from the same region- and sector-level data on gross value added that inform our dependent variable. We construct an absolute Gini index of specialization to measure the inter-sectoral heterogeneity within regions, which is calculated by the standard Gini equation:

where yijt represents region j’s value added (GVA) in sector i (i = 1,…,n, the sectors ranked in ascending order) in year t as a share of total value added in that given region and year. Specifically:

Our measure summarizes the sectoral variation and produces a panel data set consisting of 3,308 region-year observations. The absolute Gini index remains very stable over our sample period 2000–2013, increasing by merely half a per cent with no interruption from the 2008-09 crisis. Variation among regions also remained steady. Footnote 11 The steadiness of specialization in the period under study is helpful for our research design because it allows us to isolate the potential impact of a sudden asymmetric shock.

The absolute Gini index is only one of several possible ways to measure specialization. As a robustness check, we also calculate a “relative Gini index” to measure the inter-sectoral heterogeneity between regions in the EU (Dixon et al. 1987) and we find it to produce nearly identical results. Nonetheless, following Aiginger and Rossi-Hansberg (2006), we prefer to use the absolute Gini over the relative Gini index because the latter is unstable for small countries.Footnote 12

Our second explanatory variable, shock, is an indicator that equals one in the year 2008 and zero otherwise. As clearly depicted in Fig. 2, 2008 brought a uniquely severe decline in production.Footnote 13 The acute drop in demand confirms that the crisis quickly spread throughout the economy and was by no means limited to the financial sector. In robustness checks, we alternatively use a continuous shock variable measured as the regional deviation in GVA from its long-term trend.Footnote 14 This accounts for the possibility that the crisis deepened over the subsequent years.

Figure 3 displays geographical variation in specialization at the outset of the crisis in 2008. The economic “core”—e.g., UK, France, Germany, and Benelux—tends to exhibit high specialization: regional GVA originates from a few sectors. By contrast, “peripheral” countries—e.g., Spain, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Romania, and Bulgaria—are more diversified. Specialization varies substantially across countries and regions within those countries; but it varies little over the years in our sample.

In summary, we test whether the most specialized regions suffered disproportionately from the 2008 economic shock. If specialization produced greater asymmetry in the downturn, we would expect to observe either that \(\varDelta \log \)(GVA) correlated negatively (or that its variance increased) with the interaction of specialization and shock.

To evaluate our predictions, we model a linear relationship between the financial crisis and specialization on the one hand, and subsequent economic performance on the other. The modeling challenge is to capture the data structure of regions nested within countries, each observed over time. A multilevel (hierarchical) model is the perfect tool for this task. It allows us to estimate both “pooled” and country-specific effects. The “pooled” portion gives the mean relationship over all NUTS-2 regions, regardless of the country in which they are located. The “unpooled” or country-specific effects give the mean relationship for the regions within each country, through the use of country random intercepts and coefficients. For instance, Spain’s estimated effect, based on annual observations of its 19 regions, will differ from Germany’s estimated effect, which is based on its 37 regions observed over time. Our baseline model is:

where μ0[k] allows countries k ∈ 1,2,...19 to have different intercepts. The random intercepts account for unobserved country-level factors. Parameters μ1[k] model country-heterogeneity by allowing slopes to vary by country. Because the multilevel model captures the structure of time series NUTS-2 panels nested within countries, it allows us to examine how countries experienced strain from asymmetric shocks. Although our reliance on observational data makes it impossible to identify causal effects, we do use a one-year lag to mitigate simple endogeneity. In summary, the interaction term captures the joint effect of the recessionary shock and specialization in 2008—i.e. an asymmetric shock—on GVA growth from 2008 to 2009 for all regions (pooled) and by country (unpooled).

The multilevel model is especially helpful in capturing the two types of asymmetric shocks. First is the asymmetry between regions within a country. Each country coefficient estimates how specialization within a country during the crisis affects subsequent economic output. Second is the asymmetry across the entirety of the European Union. The pooled coefficient estimates how specialization across the EU during the crisis affects subsequent output. If EU-wide asymmetry is what matters most, then we should observe a negative pooled coefficient and the country-specific coefficients would not be significant. If within-country asymmetry is more important, then we should observe an insignificant pooled coefficient and many statistically significant country-specific coefficients. Variation between countries is captured by the heterogeneity of the country-specific coefficients.

To improve model estimates, we control for factors that make regions and countries more likely to specialize, and thus more likely to experience asymmetric shocks. We also account for factors that insulate a region from the ill-effects of a shock.

Membership in the Eurozone is thought to reinforce a country’s economic specialization. Eurozone members have accepted Maastricht “convergence criteria” including constraints on their fiscal policy. At the same time, the coordination of policies mandated by Eurozone membership likely affects economic performance beyond what might be predicted by specialization alone—most notably their shared monetary policy as set by the European Central Bank. We control for Eurozone status using an indicator that varies by country and year and determine whether membership status is associated with worse economic performance.Footnote 15

We include basic predictors for economic output: the population density and per-employee productivity measured at the NUTS-2 region level. One might expect a more densely-populated region to have a stronger urban core with a mobile, adaptable, and highly-productive labor force and hence be better able to withstand the shock; while a region with lower pre-shock labor productivity (i.e., lower GVA per employee) might be more vulnerable to firm turnover (Melitz and Ottaviano 2008).

Another key control is trade with other member states of the EU, measured as the given country’s exports to other EU members as a portion of national GDP.Footnote 16 Trade integration is sometimes seen as stimulant to private risk-sharing (Frankel and Rose 1998; Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2005). The more firms rely on markets outside their immediate regions, and the more value chains span different member states within the EU, the less sensitive any single region may be to an economic shock. Although intra-EU exports vary cross-nationally, they remain stable over time for core EU members. Only among the newer members has trade intensified.Footnote 17 We expect that—all else equal—countries with more intra-EU exports experience less severe asymmetric shocks. A positive coefficient on trade would lend support for the idea that private risk-sharing through trade integration reduces shock asymmetry.

Our second set of controls accounts for social and fiscal policies that might make countries more or less vulnerable to an economic shock. We account for a country’s core government spending each year as a percentage of its GDP,Footnote 18 public expenditures on social transfers as a percentage of GDP,Footnote 19 and the generosity of unemployment benefits measured as the wage replacement rate.Footnote 20 Countries with more generous safety nets are thought better able to absorb the negative effects of an economic downturn.

Necessarily, some expansion of government spending occurred in the wake of the crisis and our third set of controls accounts for such factors. The European Commission was greatly concerned with “fiscal space,” or the ability of governments to run temporary fiscal deficits without threatening their public finances or external positions (European Commission 2009). The size of the response was limited in countries with large public debts and vulnerable current account positions.Footnote 21 Thus to the extent they could, some governments quickly responded by extending assistance to banks. The European Investment Bank also participated in “bailouts” by extending loans.Footnote 22 We account for each outlay, measured as a share of GDP. Despite the political importance of these fiscal responses, their scale paled in comparison to efforts implemented by the United States. To the extent that the “bailout” efforts were endogenous to the depth of the shock, we expect they were modest enough in magnitude that they did little to counteract the asymmetry.

Summary statistics are provided in the online appendix, which can be found on the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

3 Results

3.1 Effect of asymmetric shocks on total economic output

Did specialization exacerbate the ill-effects of the crisis? To evaluate this central question, we examine regressions of the yearly change in GVA on our main measure of the asymmetric shock, i.e. the interaction between shock and specialization. We find that asymmetric shocks are not the culprit: specialized regions within countries fared approximately as well as their more diversified counterparts.

First, we establish the basic correlations in our data by running a simple linear regression model. The first model in Table 1 does not include any of the hierarchical features; it only uses fixed effects by country. Model (1) shows that overall, regions that were most specialized when the crisis hit in 2008 experienced the least severe downturn.Footnote 23

Next, we present our hierarchical model results in Table 1(2) through (6). For statistical reasons, we must restrict this analysis to the subset of EU countries with at least four NUTS-2 regions.Footnote 24 Consider the pooled estimates for the asymmetric shock. Here, we find no significant effect. Had asymmetric shocks provoked more severe declines in GVA, we would have observed a significant negative coefficient on the interaction term, Specialization×Shock. This null effect appears whether we use a binary indicator for the shock year (Table 1(2)) or a continuous measure of the shock’s severity (Table 1(3)). The decline in regional GVA during this time was dramatic, with some regions experiencing as much as a 14 per cent fall in a single year, and the most substantial burden was borne by Eurozone countries.

Did specialization have any bearing at all on regional economic performance? To evaluate this possibility, we expand the model by introducing a series of control variables. Table 1(4-5) includes economic and fiscal controls. Productivity per employee tends to be higher in regions dominated by high-tech manufacturing, financial services, etc. and indeed these regions that had the most to lose declined significantly. Conversely, trade integration appears to have mitigated regional economic contractions. The more export-oriented a state’s economy, the more comfortably it could rely on demand outside its national borders and the better it fared. The significant positive coefficient on trade is consistent with the idea that private risk-sharing through trade integration reduces shock asymmetry. Social transfers—as a share of a country’s GDP—grew steadily over the sample period (column 5), displaying little deviation from the trend during the crisis year. Social spending was associated with worse subsequent economic performance, suggesting that this form of government outlays did little to buoy hard-hit regions. Unemployment benefits, measured as the average percentage of wage replacement each claimant receives, are not a significant predictor. The response of national governments and the European Investment Bank (EIB) to the crisis did not seem to play a significant role in mitigating the downturn. In model (6) we demonstrate that the “bailout” efforts were not significantly associated with subsequent economic performance.

In additional tests shown in the appendix, we found that the type of electoral system had little bearing on economic performance. Nor did the degree of district proportionality. One might anticipate that government ideology plays a role; leftist governments may tend to be more interventionist (or pursue a more Keynesian policy response to the crisis). Our additional tests suggest that leftist governments were associated with languid rebounds, although the direction of the causal arrow is far from clear.

One might argue that the full brunt of the financial crisis was not felt immediately; that there was a delay between the shock and decline in GVA. We checked this possibility by varying the temporal lag and confirmed that the downturn did emerge within one year, as originally posited in our statistical model.

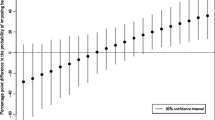

Turning our focus now to the variation across countries, Fig. 4 shows the country-effects of Specialization×Shock corresponding to Table 1(3). In six of the nineteen countries we were able to examine—Poland, Romania, Sweden, Hungary, Czech Republic, and the UK—the more specialized regions experienced especially severe declines in GVA. Otherwise, specialization was either associated with better outcomes (ten countries, including such “peripheral” member states as Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Greece) or made no difference (three countries). The country-level heterogeneity is hardly trivial: the standard deviation in random effects on the interaction term markedly exceeds that of the pooled effect.Footnote 25 As we suggest below, some of the heterogeneity can be attributed to the specific sectors in which countries specialized.

Random Effects of Specialization×Shock on Change in GVA from Multilevel Model. Random effects on interaction between specialization and shock, grouped by country. Estimates are based on Table 1(3)

Notably, all of the countries in which greater regional specialization was associated with worse regional outcomes were ones that retained their own currencies—i.e., they were not members of the Eurozone. Table 2 presents our analysis in which we compare Eurozone member states to nonmembers during the Great Recession. We use country random intercepts and our various control measures.Footnote 26 While membership in the monetary union was associated with slower economic growth over the whole period, it predicts better (or, at least, less bad) outcomes. This is consistent with the idea that use of a common currency encourages the development of risk-sharing mechanisms that can cushion the shock of a downturn.

It might still be the case that more specialized regions, even though they generally survived the shock better, exhibited a greater diversity of responses: the classic “rust belt vs. sun belt” asymmetry. We turn now to that possibility, asking (a) to what extent more diversified regions diverged from EU-wide trends, and (b) how much they diverged from the average response within their own country?

While it may seem counterintuitive, we conjecture from the Frankel-Rose perspective that deviations will have been greater within than across countries. Within countries, governments construct extensive mechanisms for public risk-sharing and regions can specialize without much private sharing of risk. Across countries, the overall EU architecture of governance is far too weakFootnote 27 to permit any reliance on public risk-sharing; hence regions can only specialize to the extent that private parties hedge against EU-wide risk.

Our logic here is similar to that propounded by Estevez-Abe et al. (2001) with respect to firm- and sector-specific production. Individual specialization is rational where generous welfare states insure against obsolescence of specific skills, and in less generous regimes individuals will insure against that risk by developing more general skills. Analogously, we expect that regions will tend to specialize within countries only to the extent that their domestic governments provide mechanisms of public risk-sharing, i.e. state aid to regions encountering hard times, and that extensive public risk-sharing will reduce incentives of firms to privately share risk by diversifying production and regional reliance. The difference will manifest during a sharp economic contraction. Under reliable public risk-sharing, specialized individuals or regions will exhibit highly varying responses; where risks are shared only privately, the response even of specialized individuals or regions will vary less.

We conducted a series of additional statistical tests, presented in the Appendix. We find that relative to EU performance, specialized regions tended on average to endure a less severe economic contraction. During non-shock years, these specialized regions differed more from EU-wide trends, providing further support that these regions tend to be more productive than less specialized regions.

Perhaps these results are not only about specialization in general, but rather, the sector in which a region specializes, in particular. Accordingly, we address the role of sectoral specialization in surviving a global economic downturn.

3.2 Sectoral effects

Our results thus far have shown that asymmetric shocks were far from the hazard they were purported to be. While regional specialization per se was associated on average, and in most countries, with better outcomes, the sector in which a region specialized also mattered. We suggest here that sectoral effects explain a great deal of the regional variation across, and even more within, countries. Table 3 displays the EU-wide loss in value-added in each of the seven sectors we consider. Clearly agriculture, manufacturing, and construction suffered most, the public sector, public utilities, and mining and quarrying least. This EU-wide measure, however, fails to capture the impact at the regional level, not least because some sectors constituted so small (agriculture), or so regionally uniform (public administration), a share of total production. Hence we replicate the multivariate regression of the preceding analysis, but include, instead of the overall Gini of specialization, the shares of regional production in sector i in year t.

We evaluate the economic performance of the regions as function of specialization in each of the sectors. We run a series of regressions where our outcome is again the percentage change in GVA and the explanatory variables are specialization in each sector. Because sector shares are compositional, we exclude sector A (agriculture) as the reference category. Country random intercepts are included, as is a dummy variable indicating Eurozone membership. Instead of using an interaction between regional specialization (here, in a specific sector) and the shock dummy, we disaggregate the analysis by year. In other words, we evaluate whether sectoral specialization predicted a particularly severe downturn during the 2008-09 crisis as compared to performance in years before and after the shock.Footnote 28 This enables a fine-grained comparison across sectors in which regions specialize.Footnote 29

Figure 5 shows the estimated effect of specialization in each sector by year with 0.95 confidence intervals.Footnote 30 There are two key points conveyed in this figure. First, the year in which the global financial crisis struck—2008—reveals a distinctive pattern. That year brought a marked downturn for most sectors, as demonstrated by the significantly negative coefficients on specialization in 2008 and positive or insignificant coefficients in other years. The second key point is that the sectors in which a region specializes matter a great deal. Again, we emphasize that the crisis quickly extended beyond its origins in the financial sector across the larger economy. Regions specialized in manufacturing (sector C) and vehicles and transportation (G-J) were hardest hit, while those whose value-added came chiefly from finance, insurance, real estate, legal services, or accounting (K-N) weathered the storm better than most. Regions with extensive public sectors (O-U) emerged relatively unscathed. Eurozone members experienced slightly better outcomes in 2008, again suggesting that the shared currency and accompanying standards may have offered some protection.

Estimated Effect of Sector Specialization on Change in GVA by Year. Estimated sector effects from model fitted with country-random intercepts. Agriculture (A) is omitted category. Years are 2006-2011. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals shown. Across most sectors, 2008 is an outlier year. Sector codes: B,D,E mining, electricity, etc., C manufacturing, F construction, G-J transportation, telecommunication, etc., K-N finance, real estate, legal, etc., O-U public administration, health care, education, etc.

The sectoral differences align well with the the cross-country heterogeneity that we have observed. In the UK, for example, the manufacturing regions of northern England were devastated to an extent that outweighed the relatively robust response of central London’s focus on financial and legal services. Here, specialization overall was associated with worse outcomes. In Austria, Belgium, and France, on the other hand, many of the most specialized regions focused heavily on the relatively unscathed public sector or on even more resilient financial, legal, or private administrative services: specialization per se was associated in these countries with better outcomes.

Finally, we explore the Frankel-Rose argument that members of a currency union pool risk as a private form of consumption smoothing, which we think correctly explains our two sets of results on specialization and Eurozone membership.

3.3 Private risk-sharing in the Eurozone

The Frankel-Rose risk-sharing explanation can be helpfully introduced with a metaphor. In times of economic trouble, risk-averse households will seek to spread economic uncertainty in various manners in order to smooth consumption—e.g., through credit or insurance mechanisms (Morduch 1995). Indeed, there is evidence of exactly this behavior by US households in response to decades of wage stagnation (Blyth 2013) and the financial crisis of 2008 (Mian and Sufi 2016). Similarly, countries (or regions) have an incentive to rely on credit to smooth consumption during an economic downturn. But, as noted previously, credit availability in the EU was entirely inadequate due to the lack of a fiscal union. The absence of independent counter-cyclic monetary policy within the Eurozone left these countries at the mercy of the European Central Bank, which followed orthodoxy during the 2008 crisis.Footnote 31 There was some effort to enable credit transfers between national central banks during the downturn through the TARGET2 mechanism (Schelkle 2017). But the benefits of this monetary credit were largely squandered by national politicians who were less than enthusiastic to enact internal fiscal adjustments (Tornell 2013). Thus, like households with no credit line or insurance to speak of, Eurozone countries (and regions) were left with few options.

Countries that select into Eurozone membership do so, in large part, on the basis of trade ties. The more a country trades with the Eurozone, the greater the potential gains to adopting the shared currency. If membership is granted, trade ties increase further as the shared currency lowers the costs to cross-border transactions. Eurozone membership should therefore correlate with high trade integration. Crucially, this trade makes the business cycles of member states more symmetric—they rise and fall together—when inter-regional trade accounts for most trade. Similar to households’ use of credit or insurance mechanisms to smooth consumption in times of crisis, regions within the Eurozone have an implicit risk-sharing mechanism via inter-regional trade. For example, if demand for German autos produced in Oberbayern (Upper Bavaria) diminishes in that region (or in Germany), demand from other regions within the Eurozone should buoy the Bavarian auto sector. Inter-regional trade may therefore serve an important risk-sharing function that pools the threat of sector-specific downturns in highly specialized regions (cf. Frankel and Rose1998).

We explore this risk-sharing mechanism using data from Thissen et al. (2018) and EUREGIO. The authors estimate regional input-output tables at the NUTS-2 level between 2000 and 2010. Using their estimates for both intermediate goods and final demand, we find that regions within the Eurozone have much stronger trade links with other regions in the currency area, than they do with regions outside the currency area. Table 4 demonstrates that inter-regional trade within the Eurozone in the years before the global financial crisis (2000-2007) accounted for 51 per cent of all Eurozone regions’ trade on average, while the remaining 49 per cent is with countries who do not share the same currency.Footnote 32 Conversely, EU regions outside of the Eurozone trade much more with other regions/countries outside of the Eurozone (58 per cent) than they do with Eurozone member states (42 per cent). As trade tends to reflect medium- to long-term structural trends, it is not surprising that these percentages remained stable between 2008 and 2009.

These rough calculations suggest that Eurozone trade links offer regions an insurance policy through inter-regional trade. When demand declines in a home region, demand from another region within the currency area can smooth income losses. Given the scope of this short research note, we are not able to fully test the risk-sharing mechanism, leaving this empirical venture to future work. However, we do believe this provides suggestive evidence of private risk-sharing at work within the Eurozone, supporting the Frankel-Rose hypothesis of endogenous optimum currency areas.

4 Discussion: Specialization and EU stability

Our results suggest that both the euro project and the EU more generally are Janus-faced. While there can be no doubt that, at the country level, the euro often served as a “golden straitjacket” that forced internal devaluation on such member states as Greece, Ireland, and Portugal—and, as we see from the consistently negative coefficient on Eurozone membership in Table 1, on regions within the Eurozone generally—it worked also, as the Maastricht framers intended, to deepen interregional ties and to cushion specialized regions against adverse economic shocks. Countries that maintained their own currencies likely did so, at least in part, because they anticipated that their future shocks would deviate more from the central tendency of the EU. In the severe shock of 2008-09, they could indeed adjust more rapidly by devaluing externally. At the same time, their very flexibility may have created a degree of moral hazard, encouraging highly specialized regions to rely on implicit mechanisms of public risk-sharing that, in the event, proved inadequate. Specialized regions within the Eurozone, and those who invested in them, had to hedge against the possibility of asymmetric shocks; and, on the evidence presented here, did so with some success.

We see that although both the EU and the Eurozone have fostered greater regional specialization, those more specialized regions have not suffered the most in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In the EU as a whole, the most specialized regions actually survived the crisis much better than did more diversified regional economies. Only in countries outside the Eurozone—notably in the UK, Sweden, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, and Poland—did the most specialized regions experience a significantly sharper downturn. Nor can this have owed to any failure of those member states to intervene fiscally to meet the crisis. Most responded more aggressively than did the EU on average, and in almost all cases more aggressively than did the comparatively slothful European Central Bank. To be sure, manufacturing suffered the worst downturn of all sectors; but over-specialization in manufacturing cannot explain the negative relationship between specialization and outcomes in the non-Eurozone states. Some Eurozone states’ regions were equally specialized in manufacturing, yet their specialization was associated with nothing like the downturns that emerged in non-Eurozone states, perhaps most sharply and ominously in the United Kingdom.Footnote 33

While our findings are by no means conclusive, they tilt the balance toward support for the Frankel-Rose hypothesis. The sharing of a common currency seems endogenously to have brought the Eurozone closer to being an optimum currency area, one in which risk-sharing has allowed the most specialized regions to survive an adverse shock better, and with less variance, than ones with more diverse economies. This risk-sharing is almost certainly private—through inter-regional trade, where external demand replaces depressed local demand—because public mechanisms remain relatively weak. Within the Eurozone, inter-regional trade actually increased as a percentage of total trade during the 2008-09 economic shock, providing further evidence of this private risk-sharing mechanism. As global demand waned, demand from within the currency union insured against even greater losses. Revisiting our example from earlier on trade in wine and cars, although there were severe drops in wine sales in Europe during the 2008-09 economic shock,Footnote 34 the northern Italian manufacturing sector continued exporting vehicle parts to the southern Germany manufacturing sector, while southern Germany continued exporting finished vehicles to northern Italy.Footnote 35 This interdependence between regions and industries within the Eurozone provides an insurance policy against economic catastrophe.Footnote 36 Notably, our empirical findings appear consistent with certain predictions of new-new trade theory (e.g. Melitz 2003). If the very specialized regions had the most productive (“superstar”) firms—which tend to export/import several goods and services to/from several countries and regions—this could explain why specialized regions were hit less hard during the crisis. This mechanism would lend further support to the idea that private risk-sharing helped to provide a form of insurance because as local (regional) demand dropped, external demand filled the void, most powerfully for specialized regions. Future research could tease out this mechanism.

Our results bode surprisingly well, despite current anxieties, for the future of the European Union as it encounters economic shocks. The EU’s novel approach to deep economic integration—a two tiered arrangement that demands governments uniformly eliminate barriers to trade while allowing governments to elect whether or not to retain autonomy over monetary policy—may very well prove to be a sustainable compromise. It was precisely within member states of the Eurozone that specialized regions experienced a more symmetric downturn; it was precisely in many of the non-Eurozone members of the EU that specialized regions experienced worse, and more asymmetric, shocks. The former had to rely on a slow and meager response from the European Central Bank; the latter governments enjoyed greater freedom to move quickly to buffer the shock. As Willett et al. (2010) aptly stated: “The euro has proved neither to be the disaster that the strongest critics predicted nor the rose garden envisioned by some of its strongest supporters” (p. 868). Far from tearing the EU apart, the 2008-09 crisis illuminated the extent to which the EU is incentive compatible: as member states have committed to more encompassing European obligations and their markets have become more integrated, they seem to have gained resiliency.

Notes

We emphasize here that we focus on how the 2008-09 slump in aggregate demand affected production across the EU rather than narrowly on the financial aspects. We do not examine the subsequent sovereign debt crisis due to the many endogenous features that prevent a clean estimation strategy.

See the online appendix, available on the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

These countries include the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

The Cohesion fund allocated 213 billion euros between 2000-2006; 347 billion euros between 2007-2013; and 450 billion euros between 2014-2020.

The financial crisis, which resulted from US regulatory failures and decisions by individual banks and pension funds, quickly spilled over to Europe. By contrast, the sovereign debt crisis that started in the Eurozone 18-months after the financial crisis hit, was the direct consequence of centralized policy-making by the ECB and was therefore far more endogenous. As confirmed by Tooze (2018, p. 6), “The historical narrative seemed to neatly arrange itself with a European crisis following an American crisis, each with its own distinct economic and political logic.”

The first difference using the natural logarithm, \(\log (\text {GVA})_{t+1} - \log (\text {GVA})_{t}\), approximates a year-over-year percentage change.

Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia were officially admitted in 2004. Bulgaria and Romania joined in 2007. Crotia joined in the final year of our sample, 2013.

For reasons discussed below, we must restrict our analysis to countries with at least four NUTS-2 regions, thus omitting from our analysis Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta, and Slovenia.

These regions were located within Belgium, Greece, Finland, France, Netherlands and Slovakia.

The mean Gini in 2000 was 0.366; in 2013 it was 0.386. Over the same period, the median displayed only a minor increase from 0.365 to 0.384, while the standard deviation remained steady at 0.066.

The relative Gini index was developed as a “bootstrapping” technique by Dixon et al. (1987), modified by Damgaard and Weiner (2000), and critiqued by Palan (2010). The relative and absolute measures are inversely correlated (− 0.22). Aiginger and Rossi-Hansberg (2006) argue that Gini indices, in general, are known to be skewed by the shares in the middle of the distribution and recommend measuring the share of the largest three industries in a region. Accordingly, we calculated the sector share and find that it correlates well with the absolute measure (+ 0.96).

The decision to classify 2008 as the shock year is further validated by time trends in trade, which reveal a significant drop in demand, as we discuss in the Appendix.

The long-term trend in regional GVA is obtained using the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter.

Several countries became EMU members in the middle of our sample: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Slovakia (2009), and Estonia (2011). We account for their status during and after the crisis.

While related studies have examined bilateral and intra-industry trade data, national aggregate trade flows are sufficiently granular for our purposes.

In robustness checks, we control for duration of EU membership.

Core government spending is the amount spent by the national government net of interest and transfer payments.

Social transfers are social transfers in kind, which are part of the discretionary, a-cyclical spending netted out of core government spending.

Unemployment benefits are measured as the initial net rate of wage replacement for an average-income earner. This variable is preferable to unemployment benefit spending, which is endogenous to the downturn.

Additionally, countries with high specialization in the public sector require large core government expenditures that may limit the fiscal space available to respond to surprise downturns. In robustness checks, we controlled for public sector specialization.

The EIB lends to private firms for the purposes of European integration, private and financial sector development, infrastructure development, energy security, and environmental sustainability. During the crisis, most loans to EU member states were in energy (Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Romania), manufacturing (Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal), construction (Austria, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, UK), and the financial sector (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Slovakia).

Standard errors are clustered by NUTS-2 region to account for the panel structure of the data.

The restricted sample consists of: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom. Omitted are Cyprus, Estonia, Croatia, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia and Slovenia because they have three or fewer NUTS-2 regions. Results are robust if we vary the threshold for number of NUTS-2 regions.

Using both 2008 and 2009 as the shock years yields similar effects. The standard deviation in random effects on the interaction term is 0.039; that of the pooled effect 0.026.

We do not use random slopes in this table to avoid over-fitting problems.

Recall that the EU budget amounts to less than 1 percent of EU GDP, while the average member state controls over 40 per cent of its GDP.

Our modeling approach is more transparent than fitting a single multilevel model where the unit of analysis is the sector-year-region and regions are nested within countries.

As before, we restrict the sample to countries with at least four NUTS-2 regions.

For simplicity, we only present coefficients for years 2006 through 2011; years before and after display similar patterns.

It was not until the 2012 Euro crisis that the ECB used unorthodox policies to supply credit.

These calculations do not account for trade within a country across its own internal NUTS-2 regions, or intra-regional trade. Rather, we focus here on extra-country trade, which is the type of trade suggested in the Frankel-Rose hypothesis. Willett et al. (2010) report that intra-Eurozone trade as a percentage of GDP grew from 25 per cent in the mid-1990s to over 40 per cent by 2000, further illustrating the importance of this trade for the overall economy of the Eurozone.

On the relationship between regional economic decline and support for Brexit, see Colantone and Stanig (2018a).

At the same time U.S. imports of European wine remained strong, thus weakening the blow to the French and Italian wine industries.

Data obtained from https://oec.world/ on August 4, 2020.

Our findings may also lend insight into the languid attempts to implement a European Unemployment Benefits Scheme (EUBS). Asymmetric shocks may not have generated as much tension across the EU as feared, the financial crisis of 2008-9 did not contribute to demand for the inter-state transfers a EUBS would provide.

References

Aiginger, K., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2006). Specialization and concentration: A note on theory and evidence. Empirica, 33(4), 255–266.

Alesina, A., Barro, R.J. , & Tenreyros, S. (2002). Optimal currency areas. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 9072.

Amiti, M. (1998). New trade theories and industrial location in the EU: A survey of evidence. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 14, 45–53.

Arpaia, A., Kiss, A., Palvolgyi, B., & Turrini, A. (2016). Labour mobility and labour market adjustment in the EU. IZA Journal of Migration, 5 (1), 21.

Autor, D.H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G.H. (2016). The China shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade. Annual Review of Economics, 8, 205–240.

Basso, G., D’Amuri, F., & Peri, G. (2018). Immigrants, labor market dynamics and adjustment to shocks in the Euro Area. NBER Working Papers 25091 National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Bauer, M.W., & Becker, S. (2014). The unexpected winner of the crisis: The European Commission’s strengthened role in economic governance. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 213–229.

Bayoumi, T., & Masson, P.R. (1995). Fiscal flows in the United States and Canada: Lessons for monetary union in Europe. European Economic Review, 39 (2), 253–274.

Bechtel, M.M., Hainmueller, J., & Margalit, Y. (2014). Preferences for international redistribution: The divide over the eurozone bailouts. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 835–856.

Bentivogli, C., & Pagano, P. (1999). Regional disparities and labour mobility: The euro-11 versus the USA. Labour, 13(3), 737–760.

Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity: The history of a dangerous idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & Schramm, M. (2006). Putting New Economic Geography to the Test: Free-ness of Trade and Agglomeration in the EU Regions. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 36, 613–635.

Ciccone, A. (2002). Agglomeration effects in Europe. European Economic Review, 46, 213–227.

Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018a). Global competition and Brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218.

Colantone, I., & Stanig, I. (2018b). The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 936–953.

Damgaard, C., & Weiner, J. (2000). Describing inequality in plant size or fecundity. Ecology, 81, 1139–1142.

Decressin, J., Fatas, A., & et al. (1994). Regional labor market dynamics in Europe.

Dixon, P.M., Weiner, J., Mitchell-Olds, T., & Woodley, R. (1987). Bootstrapping the gini coefficient of inequality. Ecology, 68, 1548–1551.

Eichengreen, B. (1990). One money for Europe? Lessons from the US currency union. Economic Policy, 5(10), 117–187.

Enrico, M. (2011). Local labor markets. In Handbook of labor economics, (Vol. 4 pp. 1237–1313): Elsevier.

Estevez-Abe, M., Iversen, T., Soskice, D., & et al. (2001). Social protection and the formation of skills: A reinterpretation of the welfare state. In Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage, Vol. 145.

European Commission. (2009). Economic crisis in Europe: Causes, consequences and responses. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication15887_en.pdf.

Frankel, J.A., & Rose, A.K. (1998). The endogenity of the optimum currency area criteria. The Economic Journal, 108(449), 1009–1025.

Frieden, J.A. (2015). Currency politics: The political economy of exchange rate policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Frieden, J., Gros, D., & Jones, E. (1998). The new political economy of EMU. Lanham, MD, and Oxford, England: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Georgiadou, V., Rori, L., & Roumanias, C. (2018). Mapping the European far right in the 21st century: A meso-level analysis. Electoral Studies, 54, 103–115.

Hodson, D. (2011). Governing the euro area in good times and bad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jauer, Julia, Liebig, Thomas, Martin, John P, & Puhani, Patrick A. (2019). Migration as an adjustment mechanism in the crisis? A comparison of Europe and the United States 2006–2016. Journal of Population Economics, 32 (1), 1–22.

Jonung, Lars, & Eoin Drea. (2009). The Euro: It Can’t Happen. It’s a Bad Idea. It Won’t Last: US Economists on the EMU, 1989 - 2002. Economic Papers, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission (395).

Kalemli-Ozcan, Sebnem, Sørensen, B.E., & Yosha, O. (2001). Economic integration, industrial specialization, and the asymmetry of macroeconomic fluctuations. Journal of International Economics, 55(1), 107–137.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sørensen, B.E., Yosha, O., Huizinga, H., & Jonung, L. (2005). Asymmetrix shocks and risk-sharing in a monetary union: Updated evidence and policy implications for Europe. In The Internationalization of Asset Ownership in Europe (pp. 173–204): Cambridge University Press.

Krause, A., Rinne, U., & Zimmermann, K.F. (2017). European labor market integration: What the experts think. International Journal of Manpower.

Krugman, P. (1991). Geography and trade (Gaston Eyskens lecture series). Leuven Belgium: Leuven University Press; Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press.

Melitz, M.J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Melitz, M.J., & Ottaviano, G.I.P. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. The Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2016). Who bears the cost of recessions? The role of house prices and household debt. In Handbook of Macroeconomics, (Vol. 2 pp. 255–296): Elsevier.

Morduch, Jonathan. (1995). Income smoothing and consumption smoothing. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(3), 103–114.

Mundell, R.A. (1961). A theory of optimum currency areas. American Economic Review, 51, 657–665.

Naz, A., Ahmad, N., & Naveed, A. (2017). Wage convergence across European regions: Do international borders matter? Journal of Economic Integration:35–64.

Obstfeld, Maurice. (1996). Models of currency crises with self-fulfilling features. European Economic Review, 40(3-5), 1037–1047.

Palan, Nicole. (2010). Measurement of specialization: The choice of indices. Forschungsschwerpunkt InternationaleWirtschaft, Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research, and Economy http://www.fiw.ac.at, Accessed 5 September 2014. FIW Working Paper no. 62. Sala-i Martin, Xavier, and Jeffrey Sachs. 1991. Fiscal federalism.

Sala-i Martin, X., & Sachs, J. (1991). Fiscal federalism and optimum currency areas: Evidence for Europe from the United States. Technical report National Bureau of Economic Research.

Schelkle, W. (2017). The political economy of monetary solidarity: Understanding the Euro experiment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thissen, M., Lankhuizen, M., van Oort, F., Los, B., & Diodato, D. (2018). EUREGIO: The construction of a global IO DATABASE with regional detail for Europe for 2000–2010.

Tooze, A. (2018). Crashed: How a decade of financial crises changed the world. Penguin.

Tornell, A. (2013). The tragedy of the commons in the Eurozone and Target2.

Willett, T.D., Permpoon, O., & Wihlborg, C. (2010). Endogenous OCA analysis and the early euro experience. The World Economy, 33(7), 851–872.

Acknowledgments

We thank Friederike Kelle, Axel Dreher, three anonymous referees, and the participants at the IC3JM workshop (2014), the Center for European Studies conference (2016), and the International Political Economy Society conference (2016) for helpful comments. Flaherty acknowledges that this material is based in part upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. 2018241622. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Rogowski is grateful for research funding from New York University, Abu Dhabi. Weldzius gratefully acknowledges support from Washington University in St. Louis and the Niehaus Center for Globalization and Governance at Princeton University. We alone remain responsible for any errors or omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peritz, L., Weldzius, R., Rogowski, R. et al. Enduring the great recession: Economic integration in the European Union. Rev Int Organ 17, 175–203 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09410-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-020-09410-0