Abstract

To scale up pedagogical innovation using information and communications technology (ICT), educators have shifted the focus of professional development from primarily an individualist endeavor to a collective approach including teachers' social networks (SNs). SNs have been found to be a major contributor to professional development and support, which in turn promote teachers' self-efficacy and improve their teaching practices. However, the effects of SNs in pedagogical innovation may vary depending on the structure of SNs and the quality of the interaction in a network. It is necessary to reconsider the assumption that the more networked teachers become, the better they teach students. This study aims to explore both the supportive and obstructive roles of teachers' SNs in scaling up ICT-based instruction through in-depth interviews with 14 primary school teachers (7 active and 7 passive ICT using teachers) in South Korea. This study found that some SNs played a positive role in supporting ICT-based instruction and professional development, whereas some imposed constraints on using ICT for teaching and learning. Teachers who actively conducted ICT-based instruction were likely to have appropriate countermeasures to obstructive SNs. This study suggests that systematic supports are necessary to help teachers expand their supportive SNs in and out of schools and to develop professional competencies to overcome the negative impacts of obstructive SNs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) has played a crucial role in the development of education (UNESCO 2019; OECD 2019a). Governments around the world have invested in the latest technologies and urged schools to adopt ICT-based instruction (OECD 2019a). Consistently, South Korea has made six master plans for ICT in education since 1996, equipping schools with ICT-based infrastructure and supporting ICT-based instruction through curriculum reform and the professional development of teachers (MoE and KERIS 2018).

Nevertheless, the OECD (2019b) reports that South Korea ranks the lowest among OECD countries in regard to the frequency of ICT usage for instruction. In the exam-oriented society, a number of students compete to gain higher scores on the college entrance exam, which consists of multiple choice questions (Kim and Cho 2014). Because the exam seldom assesses key competencies such as creativity, critical thinking, and collaboration skills, ICT has been mainly used for transmitting knowledge rather than supporting knowledge building and competency development in South Korean schools. In addition, the government has applied a top–down approach to implement ICT policies in education. The lack of teachers' autonomy has discouraged them from actively participating in professional development programs for ICT-based instruction (Seo 2013). It is necessary to empower teachers in order to overcome the challenges of ICT-based instruction and scale it up.

The social network perspective (SNP) provides a new insight to understand the role of teachers in ICT-based school innovation (Sykes et al. 2009). The attention that was previously focused on improving teachers' ICT-based instruction through school policies has now shifted to the nature and quality of teachers' social interaction as critical contributors to sustaining and scaling up ICT-based instruction. Wu and Wu (2001) propose that ICT-based instruction is diffused through not only administrative policies but also through the interpersonal exchanges among organization members. Previous studies have shown the value of SNP by establishing the importance of teacher interactions for leadership (Polizzi et al. 2019; Lin et al. 2018). By elucidating the dynamics of teachers' social networks (SNs), this study aims to understand the challenges of scaling up ICT-based instruction and explore the effective measures for the implementation of ICT-based instruction at the ground level in schools. This study can provide meaningful implications of ICT-based instruction to East Asian countries that share similar school culture and contexts with South Korea.

Literature Reviews

An SN is defined as “a set of socially relevant nodes connected by one or more relations” (Marin and Wellman 2011, p. 11). Nodes are the elemental basis of a network and typically represent individuals or organizations, but in principle, they can be any unit of analysis that connects to others such as departments, schools, districts, or even countries (Kilduff and Krackhardt 1994; Wasserman and Faust 1994). Relations can be characterized as the possible ways in which these particular units or nodes are connected with each other (Wasserman and Faust 1994). The structure of an SN can be analyzed in regard to the pattern of social supports, constraints, and embedded resources that an individual can receive through his or her network (Sykes et al. 2009). Through this analysis, SNP can provide a more complete and holistic understanding of the resource mobilization process, the role of individual agency in a network, and the complex phenomena of an education system (Serrat 2017).

Many studies on teachers' SNs for improving their instruction highlight the importance of teachers' interactions with others (Coburn et al. 2012). First, SNs allow teachers to share useful resources (e.g., instructional materials, advice, feedback, and emotional support) that are beneficial for the competencies and knowledge of ICT-based instruction (Butter et al. 2014; Duncan-Howell 2010). In addition, SNs have a positive impact on teachers' self-efficacy, which increases the intention to use ICT for teaching and learning (Gleeson and Tait 2012). Teachers with more and stronger connections to nodes in SNs are likely to have a higher level of self-efficacy due to their greater access to tacit knowledge and information on ICT-based instruction (Siciliano 2016). Furthermore, strong relationships with other teachers tend to foster collaborative norms that work to achieve common goals (Siciliano et al. 2017; Frank et al. 2014) and diminish teachers' feeling of isolation (Ranieri et al. 2012; Schreurs and De Laat 2014). Coburn et al. (2012) found that teachers’ SNs played crucial roles not only in adopting and implementing pedagogical innovation but also in sustaining it after initial supports and resources were withdrawn. In the study, most teachers who improved their instruction on the basis of a student-centered mathematics approach had SNs with strong ties, high expertise, and in-depth interaction. To scale up and sustain ICT-based instruction, teachers need to build SNs in which they constantly interact with other teachers and experts in order to discuss pedagogical issues such as what types of ICT are beneficial for learning and teaching, why they should use ICT in education, and how they can improve teaching practices using ICT.

Despite the benefits of SNs, there are difficulties in building SNs among teachers within the school context (White 2013). Teaching is perceived to be an isolated profession with teachers working alone in individual classrooms (Chung and Lee 2017; Pedder and Opfer 2013). In addition, teachers are likely to consider engaging in learning communities as a time-consuming task that is merely an extra addition to their workload. Collegial interaction to share teaching experiences may not be viewed as a source for their professional development, but just another school task to perform (Chung and Lee 2017; Seo 2009). Additionally, enforced collegiality could have a potentially negative impact on a teacher's self-efficacy and motivation if the teacher does not identify with the group (Orr 2012).

The role of SNs in scaling up ICT-based instruction may vary depending on the structure of SNs and the quality of the interaction among the nodes. In this regard, it is important to examine whether SNs allow teachers to easily access the knowledge and resources that are necessary for ICT-based instruction (Fullan and Hargreaves 1996; Seo 2009). Foley and Edwards (1999) explain that the amount that an individual gains from an SN depends on the structure of the network itself and the individual's position within the network. They also highlight that “more ties are better, but one tie might be sufficient to gain access to a critical resource” (Foley and Edwards 1999, p. 165).

Although a growing number of studies have investigated the supportive role of SNs in teachers’ professional development and school innovation, the studies have not given an enough attention to the obstructive role of SNs. It is a legitimate concern that close interaction with educational stakeholders who have negative perspectives on ICT-based instruction may discourage teachers from applying advanced technologies to improve their teaching practice in school. In addition, previous studies adopted quantitative approaches to investigate the role of SNs, focusing on the structure, resources, and actors' behaviors in the SNs. The quantitative approach, however, has not sufficiently investigated how teachers experience SNs, what SNs mean to their ICT-based instruction, and how the underlying structure of SNs affects ICT-based instruction.

To address the limitations of previous studies, the current study adopted a qualitative approach to explore both the supportive and obstructive roles of teacher SNs for ICT-based instruction through interviewing active ICT using teachers (AIUTs) and passive ICT using teachers (PIUTs). The questions guiding the study are as follows:

-

(1)

How are the supportive SNs of AIUTs different from those of PIUTs?

-

(2)

How are the obstructive SNs of AIUTs different from those of PIUTs?

-

(3)

How do teachers' SNs influence their ICT-based instruction?

Methodology

Participants

This study initially involved the participation of 20 South Korean elementary school teachers (10 AIUTs and 10 PIUTs). To achieve purposeful sampling, this study examined how actively the teachers used ICT for instruction in a pre-interview session. They were asked questions about their frequency of ICT-based instruction, the purposes of ICT use, the range of ICT tools, and their attitude toward ICT-based instruction. After the pre-interview, a total of 14 teachers (7 AIUTs and 7 PIUTs) were interviewed in regard to their SNs (See Table 1). The other teachers were excluded from data collection in order to ensure that there was a large difference between AIUTs and PIUTs. All participants were South Koreans, and Table 2 shows the information of the participants coming from different schools in urban areas within or near Seoul, South Korea. This study received ethical approval from the university's Institutional Review Board and received informed consent from all participants.

Data Collection

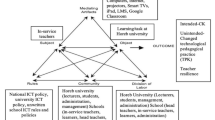

A semi-structured interview was conducted in 60–70 minutes for each participant. During the interviews, participants were first asked questions concerning their relationships with the nodes in an SN, their roles in an SN, and the resources they gain from an SN. These questions helped to acquire qualitative information on the network structure of an individual teacher's SN. Then, they were asked to articulate their perceived values and obstacles of SNs for ICT-based instruction through questions such as “Do you think your SN plays an important role for an ICT-based instruction?” and “What are the factors that inhibit you from interacting with others in SNs?” Meanwhile, participants were asked to visualize their SNs with supportive and obstructive nodes regarding ICT-based instruction. Teachers freely developed a list of the SN nodes on post-it notes (supportive nodes on blue notes and obstructive nodes on red notes) that were digitized later for better data maintenance and management (See Fig. 1). This study collected the number of nodes in supportive and obstructive SNs and the frequency of interaction between a teacher and each node from the visualized SN. Participants wrote how often they interacted with each node of the SN from 1 (rarely) to 5 (always).

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the interviews (Braun and Clarke 2006). Two researchers repeatedly reviewed the interview transcripts, generated initial codes from the data, and collated codes into 12 potential themes. Based on the themes, the entire data were once again carefully reviewed, and the themes were compared with each other. Finally, 8 themes were specifically defined, and the interview extracts regarding the themes were translated from Korean to English.

The data of SN nodes and interaction were collected from the SN visualization maps, and they were analyzed in a quantitative way. To prevent the influence of outliers, the median values were mainly used to represent the number of SN nodes and the frequency of interaction in AIUT and PIUT groups. In addition, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the SNs of AIUTs with those of PIUTs because of the uneven distribution of the data. The quantitative results were compared with the themes that emerged from the interview data. As a validity check, the participants reviewed the findings of the interviews and the SN maps with researchers. Any disagreement was discussed and clarified until a consensus was achieved.

Findings

Differences of Supportive SNs Between AIUTs and PIUTs

Supportive SN’s Boundaries

As shown in Table 3, AIUTs (Mdn = 10) had more nodes in supportive SNs than PIUTs (Mdn = 6). This difference was statistically significant according to the Mann–Whitney U-test (U = 4, z = 2.65, p = .007). Notably, as shown in Table 4, AIUTs had more outside-school nodes in supportive SNs than PIUTs (U = 4.5, z = 2.6, p = .007), although there was no significant difference in the inside-school nodes (U = 28.5, z = − .53, p = .62).

During the interviews, AIUTs mentioned a wide range of SN nodes including friends, families, alumni, and teachers in other schools (see Table 5), whereas PIUTs stated a small number of SN nodes that supported their ICT-based instruction. AIUTs had relationships with diverse actors in the private (e.g., programs offered by IT companies such as Google, Microsoft, Samsung, and SK Telecom), public (e.g., Ministry of Education), and academic (e.g., universities) sectors to share their own interests and expertise on ICT in education. AIUTs also expressed a high level of satisfaction with their relationships in SNs.

Supportive SN’s Resources

From their SN, all participants acquired resources about teaching materials, ICT skills, and pedagogical strategies that could be directly applied to their own classes. These resources were perceived to be the most valuable and helpful for teachers who lacked time to prepare ICT-based instruction by themselves due to a heavy workload in school. Teachers tended to participate in professional communities in order to share their teaching materials and experiences with ICT-based instruction. However, AIUTs had access to more diverse resources than PIUTs. While PIUTs mainly looked for teaching materials, AIUTs participated in SNs to learn new technologies, gain further information for their career development, and exchange socioemotional support. In addition, most AIUTs highlighted the quality, not the quantity, of the resources such as having meaningful learning experiences and gaining advanced ICT skills.

I become motivated by seeing how other teachers keep learning something new. (AIUT 1)

I came to know many teachers with different expertise in MIEE. Also, I gained lots of useful information from a closed workshop and a seminar that are not often publicized but found to be more beneficial and insightful than the training programs offered by the government. (AIUT 7)

Interaction in Supportive SNs

As shown in Table 3, there was no significant difference concerning the interaction frequency in supportive SNs between AIUTs and PIUTs (U = 28.5, z = − .53, p = .62). The difference between AIUTs and PIUTs was found in the quality of interaction rather than the quantity. PIUTs’ pattern of interaction with nodes in supportive SNs was a one-way interaction in which they mainly received resources from others. PIUT 7 described herself as a “downloader” in an online community and a “receiver” in an offline community. PIUTs lacked confidence in ICT skills and pedagogical knowledge, which in turn led to passive participation in creating and sharing ICT-based instructional resources. In contrast, AIUTs engaged in active interaction; they provided, received, and mediated the resources in the SNs. They continued to play critical roles as a good audience and a leader in the community to which they had once belonged. For instance, AIUT 6 participated as a leading teacher in a professional learning community in which he demonstrated his expertise on ICT-based instruction and received acknowledgement from other teachers. This community experience promoted his intrinsic motivation and self-confidence on using ICT for teaching. Compared to PIUTs, AIUTs showed more active roles and more sense of belonging in their communities, which contributed to the improvement of their knowledge of and motivation to use ICT-based instruction.

Differences in Obstructive SNs Between AIUTs and PIUTs

Obstructive SN’s Boundaries

As shown in Table 3, AIUTs had more nodes in obstructive SNs (Mdn = 4) than PIUTs (Mdn = 2), and this difference was statistically significant (U = 6, z = 2.45, p = .017). Regarding the obstructive SN nodes, AIUTs listed a range of inside-school actors such as colleagues, students, parents, and principals with whom they constantly interact. The more they tried ICT-based instructions, the more obstacles they encountered, particularly within schools. On the other hand, PIUTs were likely to perceive themselves as the main obstacle in ICT-based instruction. PIUTs, who lacked the experience with ICT-based instruction, felt greatly burdened in managing ICT devices and teaching students with new technologies.

There are many training programs offered at school regarding ICT-based instruction. But I think I am not familiar with the use of technology and do not have much interest in it. That is the key problem. (PIUT 3)

Response to Obstructive SNs

When compared to PIUTs (Mdn = 1.5), AIUTs (Mdn = 3.25) more frequently interacted with nodes in obstructive SNs (U = 7.5, z = 2.21 p = .026). AIUTs were more likely to have conflicts with SN nodes that did not support ICT-based instruction than PIUTs. Notwithstanding, AIUTs actively took countermeasures to obstructive SNs through explaining the needs of ICT-based instruction to parents, developing appropriate learning activities to increase students' positive perception of ICT-based instruction, and making appropriate ICT choices to support specific teaching and learning methods. Through applying these countermeasures, AIUTs built, maintained, improved, and re-established resiliency in the situation where ICT-based instruction was discouraged, degraded, and even rejected.

I set rules with students for ICT-based instruction. When there is a need to use smartphones in class, there are some parents who are not quite happy about it. Then, I write a lesson plan that describes my teaching philosophy, class activities, and expected learning outcomes to share with parents. (AIUT 1)

On the other hand, PIUTs do not have a proper countermeasure to the obstructive SNs that hinder ICT-based instruction.

There are two completely different groups of students in the classroom: students who can't even turn on a computer and students who have an exceptional skill in computer programming. Their ICT skill levels are too far apart, so I spend the entire class time just to respond to various kinds of questions and end up not keeping up with the class. (PIUT 7)

These quotations show that teachers' obstructive SNs deeply discourage their adoption of ICT-based instruction, but the negative influence is moderated by the countermeasures that teachers take against the obstructive SNs.

Role of SNs in ICT-Based Instruction

SNs for Better ICT-Based Instruction

The SNs enabled teachers to teach and learn from each other, exchange resources, and develop new resources together. The resources included teaching materials, ICT skills, and knowledge of pedagogies, which are useful for ICT-based instruction.

I gain lots of useful teaching materials and inspiration for my classroom instruction using ICTs from my colleagues. (PIUT 4)

To teach and share my knowledge with others, I have to keep studying different teaching materials that are useful for teachers with different interests and backgrounds. By doing so, I learn new pedagogy using ICTs that could be applied in my instruction. (AIUT 1)

Participants expressed that most teachers shared the values of reflection on teaching and learning, the desire to improve teaching skills, and the commitment to school innovation. They, however, often felt the pressure of time on administrative tasks, which hindered carrying out ICT-based instruction. To address the challenge, teachers received help from their SNs in which they shared pedagogical knowledge, discussed the concerns of ICT in education, and jointly sought methods to improve ICT-based instruction. The SNs encouraged teachers to reflect on their instruction, pursue innovative pedagogies, and build resilience to failed experiences in ICT-based instruction.

I become humbled by the way other ICT expert teachers keep studying and teaching students. Their enthusiasm, passion, and hardworking demeanour always motivate me to adopt a new teaching method from the ones with which I am familiar. (AIUT 2)

I think teacher groups have two sides like two sides of the same coin and a double-edged sword. Even if I don't practice innovative pedagogies using technologies, nobody really cares. I can stay in the traditional methods of teaching as I was taught in my childhood. However, I become more critical of my own teaching practice as I talk with colleagues, friends, and other teachers in different communities. (PIUT 2)

SNs for Teachers' Professional Development

Teachers in the study expressed an aspiration to become experts in the field of education (i.e., master teachers and textbook writers) through participating in SNs.

I joined a team of textbook writers. As a school teacher, I feel proud and committed to writing a textbook. It is certainly an unusual experience, which my peer teachers at the school do not have. And I believe this experience would deepen my knowledge and upgrade my professionalism. (AIUT 3)

I expect my participation in ATC [Association of Teaching for Computing], Google educators Groups, MIEE would become a stepping stone to having a great opportunity in the field of ICT education. Who knows if one day I will be invited as a guest speaker for the teachers' training on ICT-based instruction at the Metropolitan and Provincial Office of Education? I hope to be a renowned expert teacher in ICT-based education. (AIUT 7)

Teachers were aware of not only what they wanted to become but also what opportunities SNs presented to them so that they could turn their desire into a reality. Moreover, they associated SNs with “who I am” at present and “who I will be” in the future in their teaching careers. As expressed in the quotes above, teachers expected “self-esteem” and “social recognition” from the community around them. This social aspect constantly built and reinforced teachers' professional identity as follows: “teachers as a national curriculum builder” (AIUT 3), “teachers for teachers” (AIUT 7), and “teachers as an education diplomat” (PIUT 5).

SNs as Constraints on ICT-Based Instruction

Although teachers perceived that SNs played a decisive role in ICT-based instruction, they also recognized the obstructive SNs that often negatively influenced their teaching practices using ICT. SN nodes such as colleagues, parents, and students were not direct obstacles to ICT-based instruction, but their negative attitudes toward ICT-based instruction discouraged teachers from trying new teaching practices using ICT. Negative feedback from important education stakeholders undermined teachers' self-esteem and motivation for ICT-based instruction.

Students do not seem to take ICT-based instruction seriously. Parents assume their kids are working on their studies only when they see them with papers, not ICT devices. My colleagues think that ICT is just for teachers who are technically competent like those who majored in computer education. To me, I have more reasons not to use ICT for instruction. (PIUT 7)

In addition, teachers perceived that the government and schools would be the obstructive SN nodes when they required teachers to conduct too much administrative work such as proposal writing, school reports, and budget audits. In an interview, a teacher stated, “I have to take such time-consuming administrative tasks just to plan one ICT-based learning activity” (AIUT 7). Teachers wanted to spend more time on preparing quality instruction with new technologies rather than administrative tasks. The roles of the government and schools should be changed to empower teachers through removing excessive regulations and administrative work for ICT-based instruction.

Discussion and Conclusion

Based on the findings, this study provides implications for the educational policies and teacher training programs that are aimed at enhancing the ICT-based instruction via SNs. The implications of this study can be meaningful particularly to teachers in East Asian countries that share similar school culture and policies with South Korea. First, teachers perceived that outside-school SNs are more helpful for ICT-based instruction than inside-school SNs. This view was demonstrated stronger by AIUTs. Instead of professional learning communities within a school, AIUTs tend to participate in alternative communities out of their school’s boundaries. Their participation in these communities make them feel less inhibited in terms of publicly exercising leadership and discussing ideas and concerns about ICT-based instruction, which facilitates sharing professional values and building a sense of belonging (Fullan and Hargreaves 1996; Frost 2013). This study, therefore, recommends creating and increasing opportunities for teachers to interact with other teachers, researchers, and ICT experts beyond their own school. For this purpose, online professional learning communities can be effective in meeting teachers' demanding schedules, providing quality content and resources that are available to teachers from anywhere and at any time, and giving sustainable ongoing support for ICT-based instruction (Zygouris-Coe and Swan 2010).

Second, SNs supported not only ICT-based instruction but also teachers' professional development. Teachers expected their participation in SNs to promote leadership and social empowerment with access to a wider scale of educational communities. For instance, they wanted to join in a team of textbook writers beyond simply learning and practicing new ICT skills. The teachers, especially AIUTs, actively sought membership in communities outside of school to develop their professionalism through meaningful experiences. This finding implies that teachers' communities should not only help to enhance instructional practices by providing useful educational resources but also provide opportunities for teachers to improve their leadership and feel empowered by playing a central role as an agent of educational innovation.

Third, teachers were often constrained in how they conduct ICT-based instruction by their SNs. Teachers were likely to neglect ICT-based instruction or reduce using ICT in class after they received negative feedback from colleagues, students, and parents in school. To promote ICT-based instruction, school leaders should build collaborative school cultures among educational stakeholders and promote a dialogue on pedagogical innovation (Paulo et al. 2017). It is necessary to support participatory design in which teachers, parents, and students can all play a part in improving ICT-based instruction, such as through the following: sharing pedagogical visions, shaping collective agendas on ICT-based instruction, jointly designing a curriculum, and reflecting on the instructional practice. A participatory design with multiple stakeholders fosters a collective understanding of ICT-based instruction, which will help the inside-school SN to support, not hinder, pedagogical innovation with ICT (Cho et al. 2019).

Finally, it should be noted that PIUTs perceived themselves as the main obstacle to ICT-based instruction in their SNs. When compared to AIUTs, PIUTs had significantly fewer connections to the supportive SN nodes and less actively participated in community activities, which hindered acquiring cognitive and socioemotional supports from SNs. In addition, PIUTs were unlikely to take countermeasures to an obstructive SN, which made differences in the ICT-based instruction between AIUTs and PIUTs. Teacher educators should help PIUTs to build supportive SNs within and out of school and to develop implicit knowledge on how to address the negative attitudes of colleagues, students, and parents toward ICT in education. These supports can change PIUTs to AIUTs through increasing their knowledge and self-efficacy on ICT-based instruction.

This study contributes to the research on teachers' SNs by examining both the supportive and obstructive SNs in ICT-based instruction. Future studies, however, are necessary to address the following limitations of this study. First, this study intended to explore the role of SNs in ICT-based instruction in the context of South Korea, and thus one should be cautious when applying the findings of this study to other countries that have different education systems and school cultures. Further research is necessary to validate the findings in different contexts and to explore the novel roles of SNs in school innovation. Second, this study is descriptive in nature, so it is hard to confirm the causal relationship between SNs and ICT-based instruction. This study also has a limitation in investigating the influence of individual differences such as teachers' self-efficacy on ICT use for teaching. It is possible that individual differences influence teachers' SNs, which in turn influence their competencies in ICT-based instruction. Future research is necessary to investigate how SNs influence ICT-based instruction after controlling teachers' cognitive and affective characteristics.

References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Butter, M. C., Pérez, L. J., & Quintana, M. G. B. (2014). School networks to promote ICT competences among teachers. Case study in intercultural schools. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 442–451.

Cho, Y. H., Lee, H., Jo, G., & Pak, S. J. (2019). Effects and limitations of participatory design for teaching with digital textbooks. The Journal of Educational Information and Media, 25(4), 767–795.

Chung, B., & Lee, S. (2017). An exploratory study on the implementation of Professional Learning Community (PLC) policies in South Korea-Centered on the teachers leaders’ perceived inhibiting factors. The Journal of Korean Teacher Education, 34(4), 183–212.

Coburn, C. E., Russell, J. L., Kaufman, J. H., & Stein, M. K. (2012). Supporting sustainability: Teachers’ advice networks and ambitious instructional reform. American Journal of Education, 119(1), 137–182.

Duncan-Howell, J. (2010). Teachers making connections: Online communities as a source of professional learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 324–340.

Foley, M. W., & Edwards, B. (1999). Is it time to disinvest in social capital? Journal of Public Policy, 19, 141–173.

Frank, K. A., Lo, Y. J., & Sun, M. (2014). Social network analysis of the influences of educational reforms on teachers’ practices and interactions. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 17(5), 117–134.

Frost, D. (2013). Developing teachers, schools and systems: Partnership approaches. In C. McLaughlin & M. Evans (Eds.), Teachers learning: Professional development and education (pp. 52–69). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fullan, M., & Hargreaves, A. (1996). What’s worth fighting for in your school? New York: Teachers College Press.

Gleeson, M., & Tait, C. (2012). Teachers as sojourners: Transitory communities in short study-abroad programmes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1144–1151.

Kilduff, M., & Krackhardt, D. (1994). Bringing the individual back in: A structural analysis of the internal market for reputation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 37(1), 87–108.

Kim, Y., & Cho, Y. H. (2014). The second leap toward “world class” education in Korea. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(4), 783–794.

Klein, K. J., Lim, B. C., Saltz, J. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2004). How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 952–963.

Lin, W., Lee, M., & Riordan, G. (2018). The role of teacher leadership in professional learning community (PLC) in International Baccalaureate (IB) schools: A social network approach. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(5), 534–550.

Marin, A., & Wellman, B. (2011). Social network analysis: An introduction. In J. Scott & P. J. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social network analysis (pp. 11–25). London: Sage.

Ministry of Education (MOE), & Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS). (2018). White paper on ICT in education Korea 2018. Daegu: KERIS.

OECD. (2019a). ICT investments in OECD countries and partner economies: Trends, policies and evaluation. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019b). TALIS 2018 results (volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Orr, K. (2012). Coping, confidence and alienation: The early experience of trainee teachers in English further education. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 38(1), 51–65.

Paulo, S., Ariel, F., Sandra, G. J., & Thomas, R. (2017). OECD reviews of school resources: Chile 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pedder, D., & Opfer, V. D. (2013). Professional learning orientations: Patterns of dissonance and alignment between teachers’ values and practices. Research Papers in Education, 28(5), 539–570.

Polizzi, S. J., Ofem, B., Coyle, W., Lundquist, K., & Rushton, G. T. (2019). The use of visual network scales in teacher leader development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 42–53.

Ranieri, M., Manca, S., & Fini, A. (2012). Why (and how) do teachers engage in social networks? An exploratory study of professional use of Facebook and its implications for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 754–769.

Serrat, O. (2017). Social network analysis. In O. Serrat (Ed.), Knowledge solutions (pp. 39–43). Singapore: Springer.

Schreurs, B., & De Laat, M. (2014). The network awareness tool: A web 2.0 tool to visualize informal networked learning in organizations. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 385–394.

Seo, K. (2009). Teacher learning communities and professional development. The Journal of Korean Teacher Education, 26(2), 243–276.

Seo, K. (2013). A community approach to teacher learning. The Journal of Educational Studies, 44(3), 161–191.

Siciliano, M. D. (2016). It’s the quality not the quantity of ties that matters: Social networks and self-efficacy beliefs. American Educational Research Journal, 53(2), 227–262.

Siciliano, M. D., Moolenaar, N. M., Daly, A. J., & Liou, Y. H. (2017). A cognitive perspective on policy implementation: Reform beliefs, sensemaking, and social networks. Public Administration Review, 77(6), 889–901.

Sykes, T. A., Venkatesh, V., & Gosain, S. (2009). Model of acceptance with peer support: A social network perspective to understand employees’ system use. MIS Quarterly, 33(2), 371–393.

UNESCO. (2019). Beijing consensus on artificial intelligence and education. Paris: UNESCO.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

White, B. (2013). A mode of associated teaching: John Dewey and the structural isolation of teachers. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 15(1), 37–43.

Wu, C., & Wu, S. (2001). A study of technology integrated instruction practices problems—An example of social studies teaching. In W. Dai & R. He (Eds.), Curriculum design for information education (pp. 163–178). Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University Press.

Zygouris-Coe, V. I., & Swan, B. (2010). Challenges of online teacher professional development communities: A statewide case study in the United States. In J. O. Lindberg (Ed.), Online learning communities and teacher professional development: Methods for improved education delivery (pp. 114–133). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Pak, S. & Cho, Y.H. The Role of Teachers' Social Networks in ICT-Based Instruction. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31, 165–174 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-020-00547-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-020-00547-5