Abstract

This article focuses on Clitic Left Dislocation of XPs in French and Greek. By examining the interpretive properties of these XPs, primarily reconstruction properties, it concludes that they have been displaced from their first merge position via movement into (sometimes) a succession of hierarchically organized middle-field positions first above vP then above T and on to the left periphery via standard A or A-bar steps (no mixed options are needed). Furthermore, pronominal clitics have long raised questions regarding their surface distribution (external merge in situ only or not), and their interpretive properties. As these XPs are doubled by clitics, it becomes possible to allocate properties of the doublet (clitic, XP) to its individual members. This article concludes that these clitics all occur high, above T, in designated positions and that clitics do not have referential import, only the XPs that double them do.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Greek and French data we present in the following sections belong to the standard colloquial varieties natively spoken (respectively) by the authors and reflect their (respective) native judgements, as well as those of several adult native speakers of each of these two varieties. These judgements have been collected in informant sessions. We make explicit in which cases we detected speaker variation. Lastly, a more detailed and controlled survey was conducted in order to control for Condition C (see discussion in Appendix).

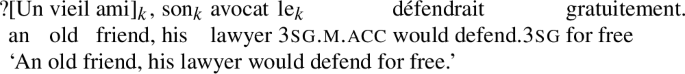

Pronominal forms can be either strong, weak or clitic in the terminology of Cardinaletti and Starke (1999). Strictly speaking, CLLD seems possible not only with clitics but with (some) weak forms too. Thus, while Nominative forms such as il in (1-a) can be clitics, see e.g. Kayne (1972), they need not be: they may also be weak forms. We will still use the term clitic for all cases, returning to this distinction in Sects. 7.4 and 11.

Throughout, we use the Leipzig glossing conventions.

This is not to say that locative PPs or predicates cannot be preposed in Greek, they can. However, they seem to have only the characteristic intonation and condition of use of focused DPs. We interpret this observation as showing that they are not really CLLD-ed. This said, if it turned out that locative PPs or predicates could indeed be CLLD-ed in Greek, that is, with a silent clitic, our analysis would not be directly impacted. In fact, we predict that CLLD of non DPs in Greek should behave in terms of reconstruction exactly as in French. Furthermore, Greek lacks the distinction between genitive and accusative clitics, which results in fewer doubling constructions. For instance, as Angelopoulos (2019) shows, complement clauses after predicates selecting PPs, like doubt or insist, cannot be doubled by an accusative clitic. This is unlike clauses after predicates permitting DP complements, like know, which can productively be doubled by the accusative clitic.

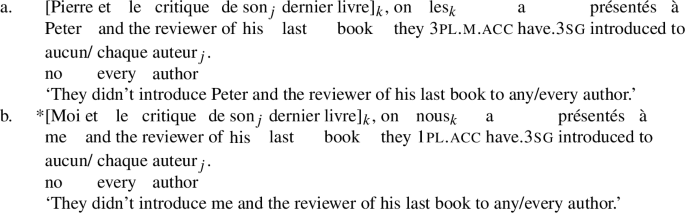

For example, Dominique Sportiche (and some other French speakers) disallows, but Nikos Angelopoulos (and some other Greek speakers, as well as some Italian speakers according to a reviewer) allows, quantified DPs such as each student to be CLLD-ed. Furthermore, (the small number of) French speakers we consulted who allow this are selective: they allow Marie pense que chaque étudiantk, Pierre lk’a invité (‘Marie thinks that each student, Peter him invited’), but not Marie pense que chaque étudiantk, ilk est venu (‘Marie thinks that each student, he came’). In other words, object QP CLLD seems relatively acceptable, but subject QP CLLD is not. We are not sure what drives this variation, which also seem to affect Clitic Right Dislocation.

One possible exception are some pseudo-cleft constructions—see den Dikken (2017) for a survey—under some analyses, e.g. Sharvit (1999), but not others, e.g. Schlenker (2003). Regardless, this does not affect the general thesis—see Sportiche (2017b)—nor its validity in the cases of CLLD as all analyses suggesting reconstruction without movement in pseudocleft specifically use properties of the verb be, which is absent in CLLD, and elsewhere.

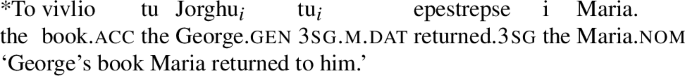

On how to evaluate Condition C effects, see the Appendix.

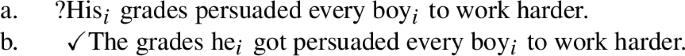

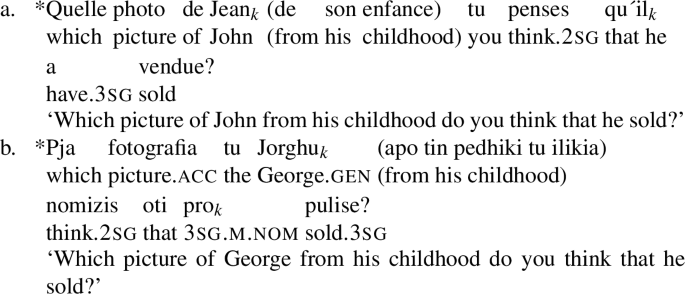

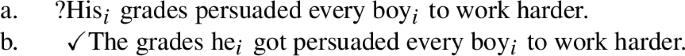

Some comments on these examples. We use these quantifiers because they do not outscope their surface positions in such cases (for example, they do not give rise to pair list readings in wh-questions). Binding of the pronoun thus cannot arise via (LF) movement of the quantifier phrase. And in all cases of pronominal binding, we choose embedded pronouns rather than highest possessors (the possessor of the whole DP). Indeed, we are interested in documenting the possibility of total reconstruction and high possessors display ununderstood properties in this respect. For instance, the first example below is less acceptable (a WCO violation) than the second, which is fine:

-

(i)

The contrast suggests that the subject can reconstruct under the QR-ed object in (b) but not in (a).

-

(i)

The French examples are all given in a colloquial register. This means in particular that certain elements required in more formal registers are omitted, e.g. the negative particle ne, inverted subject clitics, etc.

Why this is a question we are not addressing here. Sportiche (2017a) shows that the DO A-moves to its normal surface position from under an IO, if there is one (since no Condition C effect is triggered) and that the IO>DO c-command effects are due not to the IO surface c-commanding the DO, but to the possibility of reconstructing the DO under the IO.

Genitive case and dative case in Greek are morphologically syncretic. For ease of reference, we use the term dative for IOs and genitive for possessors.

Some speakers might prefer Clitic Doubling of the IO-DP in (19-b). With or without Clitic Doubling, the DO cannot bind into the IO.

We do not examine the reconstruction properties of CPs in French and Greek any further, however, it is worth noting that unlike what is reported for English (cf. Moulton 2013) they exhibit all kinds of reconstruction effects which show that they undergo movement to their surface position. As a matter of fact, CLLD-ed CPs and predicates must totally reconstruct in French and Greek, a behavior consistent, at least for predicates, with what is otherwise known, cf. Sportiche (2017b). This is explored in Angelopoulos (2019) for Greek.

What to attribute this difference between Italian and French to is unclear. If the suggestion we make about Datives in Sect. 7.4 is on the right track, it may have to do with a difference between the French and Italian PP clitics’ internal makeup, a reasonable prospect given the conclusions of Cardinaletti (2010).

What matters here is the clear evidence that there are high clitics. We remain agnostic however as to how low the low clitics are, which depends on how precisely to analyze restructuring constructions of the type discussed in Cardinaletti and Shlonsky (2004).

Where Clitic Doubling proper—the mandatory doubling of an argument (possibly in situ, but this remains unclear)—is actually found is discussed in Krapova and Cinque (2008) which shows that what is called clitic doubling in the literature conflates two distinct phenomena, only one of which they call Clitic Doubling proper. Krapova and Cinque (2008) concludes that in Bulgarian, in Greek and several other Balkan languages, Clitic Doubling proper is found with particular predicates or relations only, suggesting that the crosslinguistic prevalence of Clitic Doubling proper has been overstated—a substantial number of cases being in fact cases of (Clitic) Right Dislocation. In part because of this indeterminacy, we do not discuss Clitic Doubling here in the context of our overall analysis.

DP clitics show agreement in 1st and 2nd person, number and gender with their associate. They default to the 3rd person singular masculine neuter clitic with APs and CPs, suggesting as per Preminger’s (2009) test, that they are agreement markers rather than pronouns, as we discuss below in Sect. 5.3.

Mavrogiorgos (2010:40) notes that these adverbs can also precede clitics in Greek. Given standard assumptions, adverbs do not move themselves, thus, a reasonable assumption would be that they move along with an XP that they pied pipe when then surface before clitics.

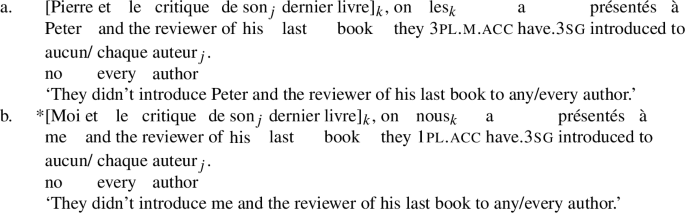

Interestingly, in these disjunctions in French, the second clitic must show liaison with a following verb but vowel elision is prohibited (with no possible outcome): Pierre le ou les

invitera (‘Pierre him or them [liaison] will invite’) but Pierre les ou *l’/*le/*la invitera (‘Pierre them or him/her will invite’). The latter also holds of disjunction of articles (le, les, un, des, etc. ‘the, the.PL, a, IND.PL’).

invitera (‘Pierre him or them [liaison] will invite’) but Pierre les ou *l’/*le/*la invitera (‘Pierre them or him/her will invite’). The latter also holds of disjunction of articles (le, les, un, des, etc. ‘the, the.PL, a, IND.PL’).We would like to thank Arhonto Terzi with whom we have extensively discussed this data. Although Mavrogiorgos (2010) discusses similar data with conjoined preverbal accusative clitics and reports them as ungrammatical at first, he notes in fn. 12 that he and Elena Anagnostopoulou (p.c.) find the data acceptable with the right intonation.

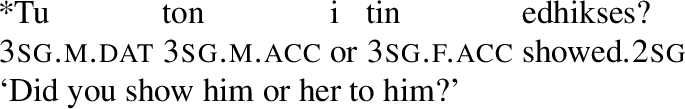

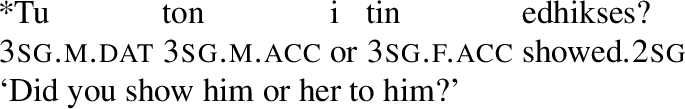

Note, crucially, that none of these disjunctions except for the first one in French are available for these clitics in postverbal positions: it could not be argued that somehow, incorporated heads can enter into disjunction. Note also that in Greek, disjunction of the accusative clitic in the presence of a dative is disallowed, as shown below, a fact we are not sure how to interpret:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Clearly, under the view in Sportiche (1996) in (30), they are not: they head a non pronominal projection. But under an updated version allowing the possibility of multiple specifiers or under a big DP approach, both discussed in Sect. 11, they could be if, for example, they are DPs. We nevertheless will conclude they are not.

Going beyond French, the possibility of clitic reduplication as documented for Italian e.g. in Cardinaletti and Shlonsky (2004:525, fn 6), also suggests that clitics are non argumental.

See Angelopoulos and Sportiche (2019) and the discussion therein of Iatridou (1986) and Anagnostopoulou and Everaert (1999). In a nutshell, the reference of the anaphor o eaftos tis/ the self his is determined by the pronoun, i.e. tis. Since the DP is an anaphor, the possessive pronoun must be bound by the antecedent of the anaphor to allow anaphor binding by this antecedent. As DP, the ϕ-features of the anaphor are determined by the features of its head noun i.e. eaftos. The phi-features of the clitic are determined by the whole DP it doubles. Binding or coreference of non pronouns does not require agreement in phi-features, as the literature on “imposters” for example shows—see Collins and Postal (2012).

The grammaticality of (36-a) poses a problem for Baker and Kramer (2018) who analyze Greek clitics as full pronouns with referential content. They claim (i) that examples like this are degraded, which they attribute to a Condition B violation, or (ii) that the doubled anaphors have a non anaphoric status. The first is examined in parallelism with the corresponding cases of Clitic Doubling in Amharic, which are ruled out according to them as Condition B violations because the clitic is locally bound by the subject. But, cases like (36-a) simply do not have the status of Condition B violations, as they have been consistently reported, e.g. in Iatridou (1986), as fully grammatical, a judgement we and other Greek speakers share. Furthermore, we show above that under Clitic Doubling, the anaphor still needs to be locally bound, which casts doubts on the claim that the doubled anaphor has a special (non anaphoric) status. This of course says nothing about Amharic clitics, which may be different from French or Greek clitics.

See also Iatridou (2000) for the use of tha in counterfactuals. The fact that free choice indefinites can only be licensed in the scope of an operator and in non episodic contexts is also noted in Giannakidou (2001) which examines the distribution of indefinites like opjiosdipote/ otidipote-‘anyone/anything’ in Greek (and other languages). See also Alexopoulou and Folli (2011) for discussion of the interpretation of CLLD-ed indefinite DPs in Greek.

For the French example, the equivalence would be with ✓Jeank croit qu’il\(_{expl}\) est supposé qu’ilk a gagné (‘John believes that it is assumed that he has won.’)

As we note several times, accenting a pronoun can lessen Condition C effects especially when there is no surface c-command of the name by the pronoun. But this is not what makes (44) fine, viz. the strong deviance of Luik mérite que Jeank gagne (‘Hek deserves that Johnk wins’/ ‘He deserves John’s winning); Luik est parti parce que Jeank était fatigué (‘He left because John was tired’), where the pronoun is accented and does c-command the name as in the text examples, but from an A-position.

Throughout, to avoid accent on the pronoun lui, extraposition intonation etc. which can alleviate Condition C, we use cleft constructions which require accent on the focus of the cleft and also guarantee embeddability of the left peripheral Topic.

Rizzi (1986) shows that silent pronouns are subject to two separate licensing requirements (see Rizzi 1986:519-520):

(i) Formal Licensing: pro is governed by a head X (of a certain type)

(ii) Content Identification: Let X be the licensing head of an occurrence of pro: then pro has the grammatical specification of the features on X co-indexed with it.

In the present case, as Rizzi (1986) takes the spec/head relation to be a subcase of local government, the formal licenser must be the clitic (or a head taking the clitic as second specifier, cf. Sect. 11) taking pro as specifier and sharing its features. The content of pro is identified by the features on the clitic.

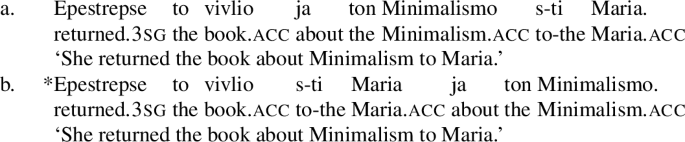

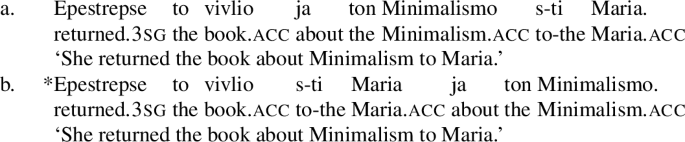

But some care is needed because of case syncretism between genitive and dative. In (48-a), tu Jorghu can be a genitive possessor in which case tis fotografies tu Jorghu (‘George’s photos’) is a single constituent or it can be analyzed as a dative indirect object in which case there are two topics i.e. tis fotografies (‘photos’) and tu Jorghu (‘George’) that have been preposed. Only the first structure with tu Jorghu as possessor is comparable to the French example in (47-c). In (48-b), the preposed phrase is a single Topic constituent in which tis Marias (‘Maria’) can only be a possessor argument because extraposition (here of the PP ja ton Minimalismo (‘about Minimalism’) is not allowed across an IO. The fact that extraposition of PPs across indirect objects is not allowed can be shown more clearly with PP indirect objects, like below:

-

(i)

-

(i)

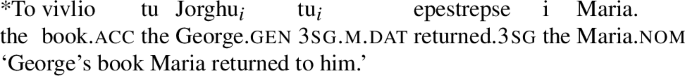

The lack of Condition C in examples like (48-a)—expected if the lowest trace is a copy of the preposed constituent—had led Anagnostopoulou (1994) to a base generation of CLLD: we reanalyze this as involving movement via an A-step.

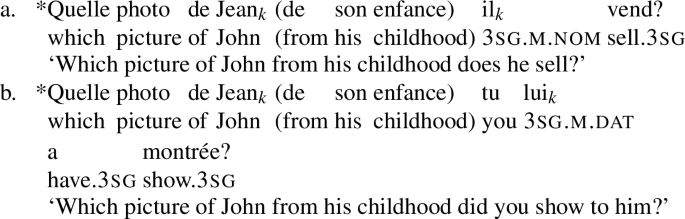

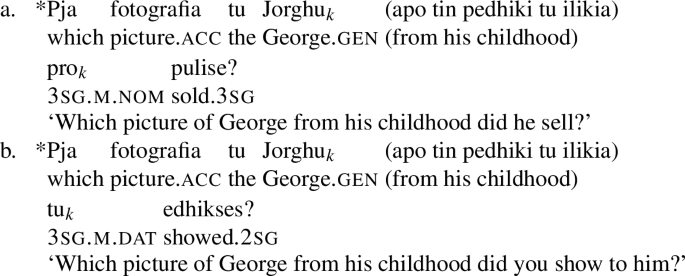

Recall that we use clefts and that we must test CLLD cases with pied piped complements to avoid late merged adjuncts.

CLLD of a pronominal DO should too. This seems correct but contrastive accent on the CLLD-ed pronoun interferes, making Condition C effects judgements less secure. C’est hier que luij, [aux voisins de Jeanj]k, Marie le\(_{*j/ \checkmark p}\) leurk a présenté. (‘It’s yesterday that him, to-the neighbors of John, Marie him to-them has presented.’).

In principle, if we could find cases of accusative clitics with relevant semantic import, we should be able to duplicate the pattern found with datives. The following case may suggest that 1st and 2nd person clitics, which we do not discuss here, exhibit such a pattern. Indeed, the following examples contrast as shown although perhaps not robustly enough to be conclusive (the same contrast is found in Clitic Right Dislocation).

-

(i)

If significant, this contrast would duplicate the third person dative/accusative contrast and could be attributed to the difference between les (‘them’) and nous (‘us’), only the latter being specified for a person property (here 1st person). It would also show that the third person dative/accusative asymmetry under reconstruction is not plausibly due to cliticized datives originating strictly higher than accusatives, since 1st (or 2nd) person accusatives show the same pattern.

-

(i)

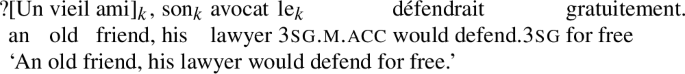

Except possibly in such somewhat degraded examples as below, cf. the second remark in fn 9:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that in principle, the CLLD-ed constituent C could be resumed by the pronoun within the subject, and bind the pro associated with the clitic. This is excluded because CLLD is movement and these pronouns are all within subject islands. But assume nevertheless that it could: C still needs to reconstruct under the modal to license the free choice interpretation. To achieve this, C would have to reconstruct into the subject, with the subject in turn reconstructing below the modal. But C would be too low (within the reconstructed subject) to bind the pro associated with the clitic. So this derivation is not available, and even if it were, it would be insufficient.

If there is a person applicative head for Datives, as mentioned in Sect. 7.4, its projection should be located between K\(_{DO}\) and K\(_{IO}\) or simply be K\(_{IO}\).

Plain arguments that undergo Focus movement should also transit through these low case positions, like CLLD-ed arguments. Nonetheless, if CLLD of a direct object can bleed Condition C with a dative clitic because of movement through these low positions, Principle C should also be bled in Focus movement. This prediction is not borne out (cf. Anagnostopoulou 1994) as shown below. More research is needed to sort this out.

-

(i)

-

(i)

We have not discussed clitic doubling per se—but cf. footnote 18—nor have we discussed Harizanov’s (2014) proposal about Clitic Doubling. This proposal postulates two distinct entities—two chain links, one of which is realized as a clitic which is m-merged as in Matushansky (2006). As discussed in Sect. 8, the m-merge part is incompatible with our findings but the idea that the clitic spells out a chain link seems compatible with our analysis, although challenges remain, e.g. (i) spelling out the realization rules (what determines the morphology of the clitic, especially if clitics such as l-ui are morphologically complex) and (ii) which chain link is spelled out as a clitic, which one as a full phrase (since movement takes place in several steps in our analysis) and why.

We limit ourselves here to Condition C triggered by epithets, which yield sharper judgements.

It should be possible to license parasitic gaps in single clauses if the adjunct containing the pg is high enough. But we have been unable to find felicitous examples in French (same with wh-movement of subjects).

This said, we find the objections to clitics heading projections given Cardinaletti and Starke (1999:fn 82, 228) unconvincing. Addressing them all in detail is beyond the scope of this article but as for the major ones: (i) Cardinaletti and Starke (1999) wrongly assumes that the general approach to clitics underlying (89) requires such distribution to hold of functional elements only, thus contradicted by, say, the existence of adverbial clitics. Assuming that the lexical/functional difference has any syntax theoretic significance—a dubious assumption—we are unclear about the basis for this assumption: our proposal can apply to any kind of projection, functional or not; (ii) it is claimed that the competition clitic>weak>strong forms cannot just as simply be stated if clitics are heads. Assuming for brevity’s sake that competition is more simply stated if among same-bar-level elements, say, the criticism of Cardinaletti and Starke 1999 does not apply as the competition could still be between XPs pro>weak>strong (where pro is the XP associate of the clitic).

The rightmost case could correspond to the case of high Datives which, as mentioned in Sect. 7.4, are more likely to be complex weak pronouns than clitics.

Recall that clitics lack semantic content although they may signal (via agreement) that their associate XP has some. We could simply apply the restriction on overt specifiers to expletives, non contentful XPs. This may also suggest that weak “pronouns” are not individual-denoting either, always in fact associated with a silent pro which is.

Angelopoulos (2019) shows that in Clitic Doubling, a doubled phrase moves to a middle field position (higher than the VP internal subject position, but lower than spec, TP, and so is able to bind a, or into a, reconstructed subject without WCO problems, for example).

If CL had semantic content, this derivation would wrongly predicts that the CLLD-ed XP must totally reconstruct to below CL to avoid a proper binding violation of the CL trace.

Note in addition, that if Baker (1988) is right about incorporation into a head H being restricted to the head of the complement of H, incorporation as in option (ii) is generally prohibited, ruling it out as well.

Pace Bošković (2019) who proposes that extraction of the clitic in a big DP conjunct is possible because it sits at the edge of bigDP (thus not causing labeling problems). However, as far as we can see, this proposal overgenerates, allowing extraction of a clitic doubling either the first or the second conjunct freely, something that is not possible in Greek—and to the best of our knowledge not attested.

Note the contrast between (97-c) in which there would be Case connectivity, as diagnostic of CLLD, and the French (96-a) in which there is no visible Case connectivity, which could thus be analyzed as HTLD, or possibly extraction from a DP peripheral Topic position as discussed in Sportiche (2018).

Note in particular that the fact that there may sometimes be morphophonological lack of compositionality (suppletion) when two clitics are adjacent is hard to interpret. Thus, despite the absence of any evidence of syntactic incorporation of the article into the preposition, French prepositions à/de followed by the article le yields the forms au [o]/du [dü], but only if the article is not itself followed by a vowel initial word (thus de le pain (‘of the bread’) → du pain, but de le ami (‘of the friend’) → de l’ami/*du ami. This suggests purely phonological conditioning rather than morphosyntactic conditioning.

The syntax of postverbal clitics, as are found in e.g. imperatives, raises additional challenges: thus different combinations are allowed, their order is typically not fixed, and disjunction possibilities are much more restricted, if possible at all.

References

Adger, David, Alex Drummond, David Hall, and Coppe van Urk. 2017. Is there Condition C reconstruction? In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 47, eds. Andrew Lamont and Katerina Tetzloff, 192–201. Amherst: University of Massachusetts GLSA.

Agouraki, Yoryia. 1992. Clitic-left-dislocation and clitic doubling: A unification. Working Papers in Linguistics 4: 45–70.

Alexopoulou, Theodora, and Raffaella Folli. 2011. Topic-strategies and the internal structure of nominal arguments in Greek and Italian. Ms., University of Cambridge and University of Ulster.

Alexopoulou, Theodora, and Dimitra Kolliakou. 2002. On linkhood, topicalization and clitic left dislocation. Journal of Linguistics 38(02): 193–245.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1994. Clitic dependencies in modern Greek. PhD diss., University of Salzburg.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1997. Clitic left dislocation and contrastive left dislocation. In Materials in left dislocation, eds. Elena Anagnostopoulou, Henk van Riemsdijk, and Frans Zwarts, 151–193. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Strong and weak person restrictions: A feature checking analysis. In Clitic and affix combinations, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordonez. Linguistik aktuell / linguistics today, 199–235. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2016. Clitic doubling and object agreement. In Proceedings of the 7th nereus International workshop:“Clitic doubling and other issues of the syntax/semantic interface in Romance DPs”, arbeitspapier, Vol. 128, 11–42.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Martin Everaert. 1999. Toward a more complete typology of anaphoric expressions. Linguistic Inquiry 30(1): 97–119.

Angelopoulos, Nikolaos. 2019. Complementizers and prepositions as probes: Insights from Greek. PhD diss., UCLA.

Angelopoulos, Nikolaos, and Dominique Sportiche. 2019. Greek ton eafto: A regular anaphor. Ms., UCLA.

Angelopoulos, Nikos. 2019. Reconstructing clitic doubling. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 4 (1).

Arregi, Karlos. 2003. Clitic left dislocation is contrastive topicalization. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 9(1): 4.

Baker, Mark. 1985. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16(3): 373–416.

Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark, and Ruth Kramer. 2018. Doubled clitics are pronouns. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36(4): 1035–1088.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2003. Person licensing and the derivation of pcc effects. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistics Sciences Series 4: 49–62.

Belletti, Adriana. 1990. Generalized verb movement. Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier.

Belletti, Adriana. 1999. Italian/Romance clitics: Structure and derivation. In Empirical approaches to language typology: Clitics in the languages of Europe, ed. Henk Van Riemsdijk, 543–580. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2012. Universals in comparative morphology: Suppletion, superlatives, and the structure of words, Vol. 50. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2018. The ban on movement out of moved elements in the phasal/labeling system. Linguistic Inquiry 49(2): 247–282.

Bošković, Željko. 2019. On the coordinate structure constraint and labeling. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 36, 71–80. Somerville: Cascadilla Proeceedings Project.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2004. Towards a cartography of subject positions. In The structure of CP and IP. The cartography of syntactic structures, Vol. 2, 115–165.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2008. On different types of clitic clusters. In The Bantu–Romance connection: A comparative investigation of verbal agreement, DPs, and information structure, eds. Cécile De Cat and Katherine Demuth. Linguistik aktuell/linguistics today, 41–82. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Cardinaletti, Anna. 2010. Morphologically complex clitic pronouns and spurious se once again. In Movement and clitics: Adult and child grammar, ed. Anna Gavarró, Vicenç Torrens, Linda Escobar, 238–259. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Ur Shlonsky. 2004. Clitic positions and restructuring in italian. Linguistic Inquiry 35(4): 519–557.

Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Empirical approaches to language typology: Clitics in the languages of Europe, ed. Henk Van Riemsdijk, 145–233. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Cecchetto, Carlo. 1999. A comparative analysis of left and right dislocation in romance. Studia Linguistica 53(1): 40–67.

Cecchetto, Carlo. 2000. Doubling structures and reconstruction. Probus 12(1): 93–126.

Cecchetto, Carlo, and Gennaro Chierchia. 1999. Reconstruction in dislocation constructions and the syntax/semantics interface. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 17, 132–146.

Charnavel, Isabelle, and Victoria Mateu. 2015. The clitic binding restriction revisited: Evidence for antilogophoricity. The Linguistic Review 32(4): 671–701.

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2013. Problems of projection. Lingua 130: 33–49.

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, eds. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini. Linguistik aktuell/linguistics today, 1–16. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1977. The movement nature of left dislocation. Linguistic inquiry 8(2): 397–412.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1990. Types of a-bar dependencies, Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Collins, Chris. 2005. A smuggling approach to the passive in English. Syntax 8(2): 81–120.

Collins, Chris, and Paul Martin Postal. 2012. Imposters: A study of pronominal agreement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

De Cat, Cécile. 2007. French dislocation without movement. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25(3): 485–534.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2017. Pseudoclefts and other specificational copular sentences. In The Wiley-Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk Van Riemsdijk, Vol. 6, 3245–3383. Hoboken: Wiley and Sons.

Fox, Danny. 2000. Economy and semantic interpretation, Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1998. Polarity sensitivity as (non) veridical dependency, Vol. 23. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2000. Negative... concord? Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 18(3): 457–523.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2001. The meaning of free choice. Linguistics and philosophy 24(6): 659–735.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2018. A unified analysis of the future as epistemic modality. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 36(1): 85–129.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014. Clitic doubling at the syntax-morphophonology interface. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 32(4): 1033–1088.

Harizanov, Boris, and Vera Gribanova. 2018. Whither head movement? Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 37(2): 461–522.

Iatridou, Sabine. 1986. An anaphor not bound in its governing category. Linguistic Inquiry 17(4): 766–772.

Iatridou, Sabine. 1995. Clitics and island effects. University of Pennsylvania working papers in linguistics 2(1): 3.

Iatridou, Sabine. 2000. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31(2): 231–270.

Iatridou, Sabine, and David Embick. 1997. Apropos pro. Language 73(1): 58–78.

Kayne, Richard S. 1972. Subject inversion in French interrogatives. In Generative studies in Romance languages, eds. Jean Casagrande and Bohdan Saciuk, 70–126. Rowley: Newbury House.

Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French syntax: The transformational cycle. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Romance clitics, Verb movement, and PRO. Linguistic Inquiry 22(4): 647–686.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The syntax of verbs. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Koopman, Hilda Judith, and Anna Szabolcsi. 2000. Verbal complexes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kramer, Ruth. 2014. Clitic doubling or object agreement: The view from Amharic. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 32(2): 593–634.

Krapova, Iliyana, and Guglielmo Cinque. 2008. Clitic reduplication constructions in Bulgarian. In Clitic doubling in the Balkan languages, eds. Dalina Kallulli and Liliane Tasmowski, 257–286. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lebeaux, David. 1991. Relative clauses, licensing, and the nature of the derivation. Syntax and semantics 25: 209–239.

Lebeaux, David. 2009. Where does the binding theory apply? Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lekakou, Marika, and Kriszta Szendrői. 2012. Polydefinites in Greek: Ellipsis, close apposition and expletive determiners. Journal of Linguistics 48(1): 107–149.

López, Luis. 2009. A derivational syntax for information structure, Vol. 23. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marantz, Alec. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own lexicon. In University of Pennsylvania working papers in linguistics, vol. 4.2, eds. Alexis Dimitriadis, Laura Siegel, Clarissa Surek-Clark, and Alexander Williams, 201–225. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 37(1): 69–109.

Mavrogiorgos, Marios. 2010. Clitics in Greek: A minimalist account of proclisis and enclisis, Vol. 160. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Michelioudakis, Dimitris. 2012. Dative arguments and abstract Case in Greek. PhD diss., Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, University of Cambridge.

Moulton, Keir. 2013. Not moving clauses: Connectivity in clausal arguments. Syntax 16(3): 250–291.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29(4): 939–971.

Pescarini, Diego. 2016. The X0 syntax of ‘dative’ clitics and the make-up of clitic combinations in Gallo-Romance. In Selected papers from the 43rd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, eds. Christina Tortora, Marcel Den Dikken, Ignacio L. Montoya, and Teresa O’Neill, 321–339. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Poletto, Cecilia, and Jean-Yves Pollock. 2004. On the left periphery of some Romance Wh-questions. In The structure of CP and IP, ed. Luigi Rizzi, 251–296. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 2003. Three arguments for remnant IP movement in Romance. Asymmetry in Grammar 1: 251.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreements: Distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40(4): 619–666.

Preminger, Omer. 2019. What the PCC tells us about “abstract” agreement, head movement, and locality. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4 (1).

Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. Null Ojects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry 17(3): 501–557.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2013. Locality. Lingua 130: 169–186.

Roberts, Ian G. 2010. Agreement and head movement: Clitics, incorporation, and defective goals, Vol. 59. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rooryck, Johan. 2000. A unified analysis of french interrogative and complementizer qui/que. London: Routledge.

Rudin, Catherine. 2013. Aspects of Bulgarian syntax: Complementizers and WH constructions. Book collections on project muse. Bloomington: Slavica. https://books.google.com/books?id=v3q2MgEACAAJ.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2003. Clausal equations (a note on the connectivity problem). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21(1): 157–214.

Sharvit, Yael. 1999. Connectivity in specificational sentences. Natural Language Semantics 7(3): 299–339.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1988. A theory of floating quantifiers and its corollaries for constituent structure. Linguistic Inquiry 19(3): 425–449.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1990. Movement, agreement and case. Available at lingbuzz/000020. Reprinted in Sportiche (1998).

Sportiche, Dominique. 1996. Clitic Constructions. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 213–277. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1998. Partitions and atoms of clause structure. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203982372.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2005. Division of labor between move and merge. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/000163.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2016. Neglect (or doing away with late merger and countercyclicity). Ms., UCLA. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/002775.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2017a. (Im)possible intensionality. In Special issue: Linguistic papers celebrating martin prinzhorn, eds. Clemens Mayr and Edwin Williams. Vienna: Wiener Linguistische Gazette.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2017b. Reconstruction, binding and scope. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk Van Riemsdijk, Vol. 6, 3569–3626. Hoboken: Wiley and Sons.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2018. Resumption (resumed phrases are always moved, even with in-island resumption). In Selected papers from the 46th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL), eds. Lori Repetti and Francisco Ordóẽz. Vol. 14 of Romance languages and linguistic theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027263896.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2019. Somber prospects for late merger. Linguistic Inquiry 50(2): 416–424.

Stabler, Edward. 1996. Derivational minimalism. In International conference on logical aspects of computational linguistics, 68–95.

Stabler, Edward P. 1999. Remnant movement and complexity. Constraints and resources in natural language syntax and semantics 2: 299–326.

Stockwell, Richard, Aya Meltzer-Asscher, and Dominique Sportiche. 2020. There is always reconstruction for condition C in English questions. Ms., UCLA.

Takahashi, Shoichi, and Sarah Hulsey. 2009. Wholesale late merger: Beyond the a/ā distinction. Linguistic Inquiry 40(3): 387–426.

Terzi, Arhonto. 1999. Clitic combinations, their hosts and their ordering. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 17(1): 85–121.

Torrego, Esther. 1992. Case and argument structure. Ms., UMass, Boston.

Travis, Lisa. 1984. Parameters and effects of word order variation. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Tsimpli, Ianthi-Maria. 1995. Focusing in Modern Greek. In Discourse configurational languages, ed. Katalin É Kiss, 176–206. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1995. Aspects of the syntax of clitic placement in Western Romance. Linguistic Inquiry 26(1): 79–124.

Van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen, and Marjo Van Koppen. 2008. Pronominal doubling in Dutch dialects: Big DPs and coordinations. In Microvariation in syntactic doubling. Syntax and semantics, 207–249. Leiden: Brill.

Vergnaud, Jean-Roger. 1974. French relative clauses. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Vergnaud, Jean-Roger, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta. 1992. The definite determiner and the inalienable constructions in French and in English. Linguistic inquiry 23(4): 595–652.

Zagona, Karen. 2002. The syntax of Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Controlling for Condition C

Appendix: Controlling for Condition C

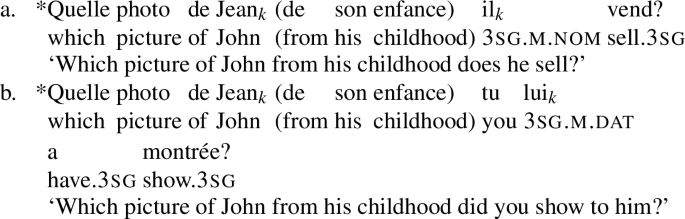

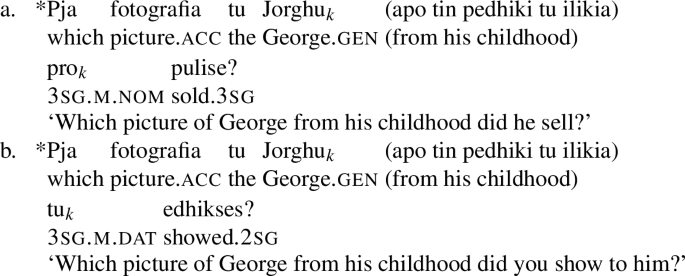

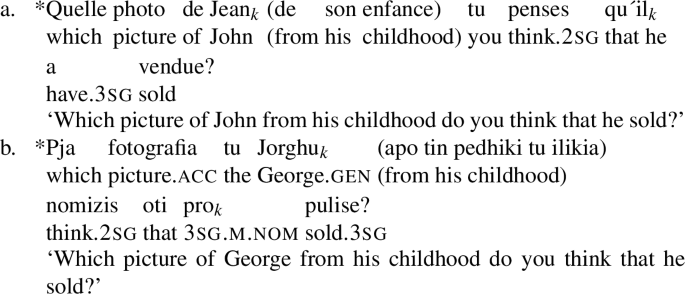

To evaluate Condition C, there are a number of confounds to avoid, some of which mentioned in the course of what precedes. It is best to avoid accent on the pronoun (focus or contrast) as this can meliorate Condition C effects. The most important precaution is to compare pairs of sentences of similar structure and complexity, one potentially violating Condition C the other not, or both potentially violating Condition C, one already reported as such, the other being evaluated; that is, pairs that are as minimally distinct as possible.

We illustrate simple cases in French (98) and Greek (99) that are used as benchmark for Condition C violations.

-

(98)

-

(99)

We further note Condition C effects decay with distance, both structurally and linearly, as reported in the literature, recently in Adger et al. (2017)) and duplicated in part in Stockwell et al. (2020). Embedded cases (French (100-a), Greek (100-b)) are perceived as less deviant than simple cases above but as equally deviant as each, as compared to sentences without coreference:

-

(100)

In particular, when evaluating the complement/adjunct asymmetry, it is important to keep the linear distance between the pronoun and the name constant.

The French and Greek data were collected in a standard manner, by asking one-on-one, on two distinct occasions each, at least nine native speakers contrastive judgements (as described above) together with a judgement of confidence (least confident 1 to most confident 5) about the judgement. The judgements on reconstructed Condition C effects were overall fairly robust (confidence > 3 per token) but showed the decay discussed above (confidence >4 for short distance). In particular these judgements are consistent with our own judgements and with what has been reported in the literature for about three decades in three respects: existence of Condition C effects with pied piped complements, complement/adjunct asymmetries and decay with distance. All the other judgements we report were consistently very robust (confidence > 4 on average, per token) and consistent with our own judgements. The French, resp. Greek, data were also presented to audiences of native speaker linguists on several occasions and did not elicit any disagreement or objections.

This contrasts with the conclusions of a small experimental study of English (40 speakers) in Adger et al. (2017) according to which (i) there are no Condition C effects with pied piped arguments and (ii) there are no argument/adjunct asymmetries. Adger et al. (2017) concludes that there are reconstructed effects for predicate preposing but not for argument preposing. A full review of this article and these conclusions is beyond the scope of the present article but we are not convinced. Concerning the existence of Condition C effect with pied piped argument, our skepticism is both based on a long history of reports of native speaker judgements in a variety of languages documenting the existence of such effects, and on the results of a just completed larger study (about 220 subjects) on English, Stockwell et al. (2020), which also shows clear Condition C effects for pied pied material both in short and long wh-movement cases. In addition, some of the data Adger et al. (2017) reports are quite noisy making conclusions insecure and in particular, it is unclear to us that these data do not in fact support the existence of Condition C effects with pied piped arguments and argument/adjunct asymmetries. More generally, the absence of effects observed experimentally strikes us as inconclusive: they take absence of evidence to provide evidence of absence, but this absence of evidence could instead be due to experimental design deficiencies, insufficient control, performance factors, biases introduced by the task itself or insufficient statistical power. More generally, while the reliability of (some) elicited judgements has been experimentally supported via experimental reduplication, the reverse has not been established. In particular, it is hard to conclude anything when experimental results conflict with consistently reported judgements, as they seem to do in English, both in case of Condition C pied piped arguments and in the contrast between argument and adjuncts. It should be noted however that no such discrepancy has (yet) been reported for French and Greek.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Angelopoulos, N., Sportiche, D. Clitic dislocations and clitics in French and Greek. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 39, 959–1022 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09500-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09500-z

invitera (‘Pierre him or them [liaison] will invite’) but Pierre les ou *l’/*le/*la invitera (‘Pierre them or him/her will invite’). The latter also holds of disjunction of articles (le, les, un, des, etc. ‘the, the.PL, a, IND.PL’).

invitera (‘Pierre him or them [liaison] will invite’) but Pierre les ou *l’/*le/*la invitera (‘Pierre them or him/her will invite’). The latter also holds of disjunction of articles (le, les, un, des, etc. ‘the, the.PL, a, IND.PL’).