Abstract

This study examined the relationships between students’ perceptions of teacher support, the social classroom environment, school loneliness, and possible gender differences among 2099 first year upper secondary school students in Norway. Data were collected in the fall (t1) and spring (t2) of the school year. Results from structural equation modelling (SEM) analyses showed that perceived emotional and instrumental teacher support were directly related to students’ perceptions of the social classroom environment, and indirectly to student loneliness through the social classroom environment. While for boys, both types of teacher support were significantly related to these variables, only emotional teacher support was of significance to girls. The strongest contributing factor to students’ school loneliness was their perceptions of the social classroom environment. Some implications of this study are that a positive social classroom environment is an important safeguard against student loneliness, and that teachers can aid in preventing loneliness among students through facilitating a positive social environment in the class.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Experiencing positive interpersonal relationships is crucial to individual’s development and wellbeing as it contributes to a sense of belonging. Conversely, experiencing a lack of such relationships can lead to a sense of deprivation, which can manifest itself in feelings of loneliness (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Heinrich and Gullone 2006). Adolescents are in a developmental period characterized by biological and social transitions and may therefore be particularly prone to feeling lonely (Goosby et al. 2013; Heinrich and Gullone 2006). Adolescence is also a time when relationships with peers relative to parents become increasingly more important (e.g. Hafen et al. 2012). Research has consistently demonstrated that the quality of students’ relationships with peers is closely linked with their experiences of loneliness at school (e.g. Heinrich and Gullone 2006). All the same it is unclear in what ways other classroom factors, such as teacher support and the social environment in the classroom, influence on students’ feelings of school loneliness, and moreover whether these associations are dependent of gender. This study thus sought to investigate the relations between students’ perceptions of social support from teachers, their experiences of the social classroom environment, and loneliness among a sample of first year upper secondary school students in Norway. A clarification of these relationships can help identify protective factors within the school context, which can be of considerable utility for teachers and others who work with adolescents in the school setting.

1.1 Loneliness

Loneliness can be regarded as a negative emotion arising out of the incongruity between a person’s desired and actual social relationships (Perlman and Peplau 1981). This adverse experience is generally considered to stem from a lack of sense of social connectedness with others rather than a lack of actual social contact. It thus refers to the quality rather than the quantity of social relationships (Heinrich and Gullone 2006; Perlman and Peplau 1981, 1982). Although most people occasionally feel lonely, some experience more persistent and severe feelings of loneliness. The adverse impact that loneliness can have on adolescents’ wellbeing has been widely documented in the literature. Studies have for instance linked loneliness during adolescence and early adulthood with poorer general health (Harris et al. 2013; Mahon et al. 1993), reduced sleep quality (Cacioppo et al. 2002), eating problems (Rotenberg and Flood 1999), and higher mortality rates (see Cacioppo and Cacioppo 2012).

The causes of loneliness are complex, and may include environmental, societal, relational as well as individual factors (e.g. Heinrich and Gullone 2006; Krause-Parello, 2008). Moreover, it can be problematic to distinguish the causes and consequences of loneliness apart, as the path of causality between loneliness and the factors commonly associated with it is often bidirectional (Heinrich and Gullone 2006). Some of the recognized predictive conditions nonetheless include characterological traits like shyness (Woodhouse et al. 2012), introversion (Hawkins-Elderet al. 2018), neuroticism (Vanhalst et al, 2012), poor social skills (Segrin and Flora 2000), and related behaviours such as social withdrawal and avoidance (London et al. 2007; Watson and Nesdale 2012). Loneliness has also been reciprocally and adversely associated with self-esteem (e.g. Vanhalst et al. 2013) and mental health problems such as social anxiety (Lasgaard et al. 2011a, b; Maes et al. 2019) and depression (Ladd and Ettekal 2013; Lasgaard et al. 2011a, b; Vanhalst et al. 2012).

Previous research has established that loneliness can occur within different contexts, such as the family, romantic relationships, and in school (Chipuer 2001; Ditommaso and Spinner 1997; Lasgaard, Goossens, Bramsen, et al. 2011a, b). The focus of the present article is adolescent loneliness in the school context. This topic has been extensively studied to date, and school loneliness has been linked with factors such as lower academic achievement (Levitt et al. 1994), impaired academic progress and exit exam success (Benner 2011), and intentions to leave upper secondary school early (Frostad et al. 2015; Haugan et al. 2019).

1.1.1 Perceived teacher support and student loneliness

Although teacher support is a broad term encompassing various dimensions, researchers have commonly distinguished between emotional and instrumental support (e.g. Federici and Skaalvik 2014; Semmer et al. 2008). Perceived emotional support refers to students’ perceptions of their teachers as caring, friendly, empathetic and trustworthy, whereas perceived instrumental support points to students’ perceptions of receiving academic help and support from their teachers.

A number of studies have documented the significant role of perceived teacher support to student’s well-being and academic adjustment (Katz et al. 2009; Malecki and Demaray 2003; Natvig et al. 2003; Patrick et al. 2007; Suldo et al. 2009; Wentzel et al. 2010). The role of the teacher in adolescent’s loneliness has however received little empirical attention. Moreover, the few studies examining these associations have mainly focused on children (e.g. Birch and Ladd 1997). As noted by Parkhurst and Hopmeyer (1999), there will likely be differences in the causes and correlates of loneliness between children and adolescents, due to changes in cognitive development and in the significance of social relationships as children move into adolescence. Although researchers have emphasized the teacher’s important role in contributing to reducing student loneliness (e.g. Galanaki and Vassilopoulou 2007; Rokach 2016), only two studies were found that provide empirical data on this association. Frostad et al. (2015) found that emotional teacher support was significantly and negatively correlated with school loneliness in a sample of Norwegian adolescents (r = −0.13). Results from an earlier study by Dobson, Campbell, and Dobson (1987) moreover showed that students’ perceptions of the quality of the classroom environment created by the teacher was inversely related to their feelings of loneliness (r = −0.20) (Dobson et al. 1987). Otherwise, this relation remains largely unexplored.

1.1.2 Social classroom environment and student loneliness

Previous research has described the social classroom environment in various ways. While some have related it to social relationships between students, and students and teachers (e.g. Patrick et al. 2007), others have linked it to the social atmosphere or climate in the classroom (e.g. Cava et al. 2010; Cava et al. 2007). With regard to loneliness, researchers have particularly devoted their attention to the peer group in school. Not surprisingly, important risk factors for school loneliness include social difficulties such as peer victimization (Lester et al. 2013; Woodhouse et al., 2012), bullying (Segrin et al. 2012) and negative peer acceptance status (Sletta et al. 1996; Woodhouse et al., 2012). Sociometric classroom studies have moreover demonstrated that lonely adolescents tend to have fewer friends in class (Lodder et al. 2017), and to report lower quality in the friendships they do have (Parker and Asher 1993; Vanhalst et al. 2014). Notably, students’ perceptions of having supportive and caring peers have been found to moderate the relationship between victimization and loneliness (Storch et al. 2003).

Little empirical attention has however been given to the associations between loneliness and social factors within the school environment that go beyond the direct relationships between peers. Results from the handful of studies that have investigated this indicate that adolescents’ perceptions of a positive classroom environment and their sense of connectedness to school are negatively related to global loneliness (β = −0.15 – −0.28) (Cava et al.2010, 2007; Pretty et al. 1994). None of these studies have however focused their attention on how the social classroom environment relates specifically to school loneliness. Given the importance of a positive social school environment for students’ wellbeing and learning (e.g. Jamal et al. 2013), this is regarded as an important area to investigate further.

1.1.3 Gender differences in perceptions of the social classroom environment, teacher support and loneliness

Considering the general lack of research on the association between students’ perceptions of teacher support, the social classroom environment and loneliness, few relevant studies were found on how gender might moderate these relationships. One exception was a study that found the relationship between the classroom environment and loneliness to be stronger for adolescent boys than girls (β = −0.28 for boys and −0.16 for girls) (Cava et al. 2010). The following section will thus review some of the literature on gender differences in levels of loneliness and teacher support.

Regarding gender differences in levels of teacher support, some studies have shown that girls tend to report higher emotional support (Låftman and Modin 2012) and a greater degree of closeness with their teachers (Drevets 1996; Wyrick 2011), whereas boys tend to report higher levels of instrumental teacher support (Låftman and Modin 2012). Results from an earlier meta-study by Kelly (1988) moreover suggested that boys tend to have more tangible and instructional contact with teachers than girls. Other empirical work has however found no gender differences in perceived teacher support (Danielsen et al. 2009).

Research on gender differences in adolescent loneliness has led to contrasting results. To the extent that gender differences have been reported among adolescents, boys have tended to display higher loneliness rates than girls (e.g. Koenig and Abrams 1999; Koenig et al. 1994). Conversely, results from the Norwegian Ungdata surveys have shown a female predominance in self-reported loneliness (Bakken 2017, 2018, 2019). Ungdata are nationally representative surveys conducted every three years among school students in Norway (from grade 5 to 13). The study covers thematic areas such as parents, friends, school, the local environment, leisure activities, health and well-being (Ungdatasenteret 2020).

In an earlier meta-study, Borys and Perlman (1985) noted that while girls were more apt to label themselves as lonely (self-labelling), boys tended to display higher loneliness scores in self-report studies. In Ungdata, loneliness was measured by use of one question asking about the degree to which the students had experienced loneliness in the last week, and this may be viewed as a form of self-labelling. These opposing findings concerning loneliness and gender may therefore, at least in part, be explained by method of assessment (Heinrich and Gullone 2006).

1.2 Purpose of the study and theoretical model

Taken together, there appears to be a gap in the literature on the associations between student’s perceptions of teacher support, the social climate in the classroom and loneliness, and on how these relations may vary by gender. There also seems to be a lack of longitudinal studies on school loneliness. The present study thus sought to extend on the previous research by investigating these variables across two time points. Findings from previous work that has emphasized the importance of positive social relationships and a positive social classroom environment for students’ loneliness, led to the formulation of two main hypotheses. Specifically, it was hypothesised that:

-

(1)

Positive perceptions of teacher support would (a) positively predict the social classroom environment and (b) negatively predict loneliness.

-

(2)

Positive perceptions of the social classroom environment would negatively predict loneliness.

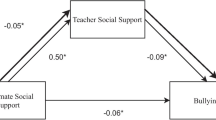

Due to the mentioned lack of, and somewhat inconsistent results presented in previous research, no gender-specific hypotheses were formulated regarding the relationships between teacher support, the social classroom environment and loneliness. Rather, these investigations are exploratory in their nature. The theoretical model is displayed in Fig. 1.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

The sample comprised 3149 first year upper secondary school students (aged 15 and 16) from 17 upper secondary schools in Norway. Data were collected twice in the school year 2017/18 by means of electronic self-reporting questionnaires administered in school classes. The first survey was conducted approximately ten weeks into the school year in 2017 (t1), and the second survey was carried out in March/April 2018 (t2). Some classes did, for unknown reasons, not respond to the survey within the allotted time. At t1 there were 24 classes in six schools that did not participate, while at t2, this applied to 19 classes in five schools. These classes constituted the bulk of non-responses. Finally, the number of participating students were 2,501 at t1, and 2,422 at t2.

The data were examined for differences in respondent characteristics between the students who participated only at t1 (n = 402) or t2 (n = 323), and those who had responded to both surveys. Chi-square tests and t-tests showed that there were no significant differences in variables such as mother’s education level, gender, mean grades, or field of study (general or vocational education) between these groups. The 725 students who had responded to only one of the two surveys were omitted from the main analyses. This yielded a final sample of 2099 students and a response rate of 67%. Of these, 1240 (59%) were female.

All schools appointed a contact person who was responsible for providing the necessary information and assistance to teachers and students. Students, teachers and parents received and information sheet, which informed that students had a right to withdraw from participation at any time, and that they were considered to have given their consent to participate by responding to the questionnaire. Prior to responding to the survey, students in each class were shown an information video recorded by the author. The video explained the rationale of the study and encouraged the students to answer the questionnaire properly. Parental consent was attained from students under the age of 16, and the project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD).

2.2 Measures

All items were designed and administered in Norwegian. The response categories for all statements except gender were on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree through 6 = strongly agree. All items were averaged for a scale score.

2.2.1 Exogenous variables

Perceived teacher support Instrumental and emotional teacher support were measured by four items each. The scale for instrumental support was modified from an instrument developed by Frostad et al. (2015) and later slightly adapted by Tvedt (2017). Example items are: ‘My teachers try to answer my academic questions’ and ‘My teachers explain to me what I don't understand’. Emotional support was modified from a widely used scale developed by the Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioral Research in Education (e.g. Bru et al. 1998; Tvedt et al. 2019). This scale comprises statements such as: “My teachers care about me’ and ‘I can trust my teachers’.

2.2.2 Endogenous variables

Social classroom environment This measure encompasses the social climate in the classroom, and more specifically students’ perceptions of having supportive relations to their peers and their sense of belonging to the class. Three of the items were adapted from questions created by the VIP School Programme (2015, 2016), and example statements are: ‘I always have someone to be with during breaks’, and ‘I have made new friends in class’. The three remaining statements were made for the present study and include items such as: ‘I always have someone to sit together with in class’. Higher scores indicate more positive perceptions of the social classroom environment.

Loneliness Loneliness was measured by using a Norwegian version of the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire (Asher and Wheeler 1985; Valås 1999). This scale has a clear school focus and has been used in several studies to measure school loneliness (e.g. Frostad et al. 2015; Galanaki and Vassilopoulou 2007). Example items are ‘I have no one to be together with at school’ and ‘I feel lonely at school’. High scores indicate higher levels of school loneliness.

Gender A dichotomous variable indicated whether the adolescent is female (1) or male (2).

3 Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS 26, whereas confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM) were conducted using the lavaan package in R. Because initial tests indicated that the residuals were non-normal, robust estimators were calculated using MLM (Maydeu-Olivares 2017; Savalei 2018). These tests require complete data, and prior to conducting the SEM-analyses, missing data estimates were computed through regression imputation with maximum likelihood (Allison 2002). Data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR), as separate variance t-tests showed that none of the items significantly affected whether data were missing in any of the other items. All items had missing values < 2.7% of the total sample. All models were based on the complete data set.

First, three measurement models were tested by using CFA. Next, the relationships between the latent variables were examined by means of SEM. SEM is a recommended analytical tool to examine relationships among latent constructs in longitudinal studies (Lei and Wu 2007). The goal of SEM is to estimate the relationships among hypothesized latent constructs, and to test whether the hypothesized theoretical model corresponds with the collected data. Due to the large sample size, χ2 was not used to evaluate model fit (Hair et al. 2014). Rather, the assessment of goodness of fit was guided by fit criteria of CFI and TLI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.07, and SRMR < 0.08 (Hooper et al. 2008; Kline 2011).

4 Results

4.1 Correlations and descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows correlations between the variables, statistical means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas and effect sizes for the mean differences between gender. All latent variables were significantly correlated with one another. All correlations were below 0.68, which implies that multicollinearity is not a concern. Boys reported higher levels of both instrumental and emotional teacher support compared to girls. Moreover, boys had significantly higher loneliness scores than girls at t2, but the effect size was small/insignificant (Cohen and Steinberg 1992). All variables demonstrated high reliability.

4.2 Measurement models

The factor structure of the latent variables was assessed by testing three measurement models using CFA. Fit statistics were compared across these models in a stepwise procedure (Hair et al. 2014). The first model included the two exogenous variables (instrumental and emotional teacher support), while the second model included the three intermediate variables (social classroom environment at t1 and t2 and loneliness at t1). Finally, the third model included all six variables. Because the data are longitudinal, the residuals for the items measuring the same phenomenon at t1 and t2 were allowed to correlate (Little 2013). Table 2 shows that the complete model had good fit with the data, and this indicates that the items constitute six distinct constructs.

4.3 Structural models

The relations between the variables were further explored by means of SEM. First, a model was constructed based on the hypothesized model shown in Fig. 1. The model (referred to as Model 1) specified emotional and instrumental teacher support as exogenous variables. These were expected to be positively related to the social classroom environment at t1 and t2, and negatively related to loneliness at t1 and t2. Moreover, the social classroom environment at t1 was expected to be negatively related to loneliness at t1 and positively related to the social classroom environment at t2. Next, loneliness at t1 was expected to be positively related to loneliness at t2, whereas the social classroom environment at t2 was expected to be negatively related to loneliness at t2. The residuals among corresponding parallel indicators at t1 and t2 were allowed to correlate. Model 1 showed good fit with the data, with robust RMSEA = 0.041 (90% CI: 0.038–0.043), CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.961 and SRMR = 0.045.

Figure 2 shows estimates of standardized regression weights for all variables and squared multiple correlations. First, instrumental and emotional teacher support were positively and moderately related to the social classroom environment at t1. While neither instrumental nor emotional teacher support were directly related to loneliness at t1, both were indirectly related to loneliness at t1 through the social classroom environment at t1 (β = −0.129, p < 0.001 for emotional support and −0.191, p < 0.001 for instrumental support). The social classroom environment at t1 was strongly and negatively related to loneliness at t1. Loneliness at t2 was strongly and negatively related to social classroom environment at t2 and positively related to loneliness at t1. The social classroom environment at t1 was moreover indirectly related to loneliness at t2 through both loneliness at t1 (β = −0.217, p < 0.001) and the social classroom environment at t2 (β = −0.431, p < 0.001). Before conducting the further analyses, nonsignificant paths and covariances were removed from Model 1. Table 3 shows that the trimmed model, referred to as Model 2, had good fit to the data.

4.4 Measurement invariance across gender

Prior to conducting separate analyses for gender, Model 2 was checked for measurement invariance. Changes in CFI ≤ −0.010 and RMSEA ≤ 0.015 from the baseline model were used as limit values (Chen 2007). Table 3 shows that the changes in the CFI and RMSEA values across the models were acceptable, and this implies that the data meet requirements of configural, metric, scalar and strict invariance (Wu et al. 2007). As such, cross-gender comparisons of the relationships between the latent factors could be conducted.

4.5 Final model with different paths for gender

Finally, a model (referred to as Model 3) was constructed that specified different paths for gender. Model 3 showed good fit to the data for both genders, with robust RMSEA = 0.044 (90% CI: 0.040–0.047), CFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.956 and SRMR = 0.048 for girls, and RMSEA = 0.037 (90% CI: 0.032–0.041), CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.966 and SRMR = 0.049 for boys. First, Fig. 3 shows a strong and positive correlation between emotional and instrumental teacher support. Moreover, emotional teacher support at t1 was positively related to the social classroom environment at t1 for both genders, but this path was stronger for girls than boys. Instrumental teacher support was significantly and moderately related to the social classroom environment only among boys. The R2 values show that the two types of teacher support account for a greater proportion of the variance in the social classroom environment variable among boys compared to girls.

The social classroom environment at t1 was furthermore strongly and negatively related to loneliness at t1, and this association was stronger for girls than boys. There was moreover an indirect and significant relation between instrumental teacher support and loneliness at t1 for boys (β = −0.186, p < 0.001), but not for girls. The indirect relations between emotional teacher support and loneliness were significant for both genders, and stronger for girls (β = −0.224, p < 0.001) than boys (β = −0.119, p < 0.01). The relations between teacher support and loneliness at t1 were mediated by the social classroom environment at t1. Figure 3 shows that a higher proportion of the variance in the loneliness variable at t1 was explained among girls compared to boys. Results moreover indicated a significant and strong relation between the social classroom environment at t1 and t2, and this path was somewhat stronger for girls than boys. The proportion of explained variance in the social classroom environment variable at t2 was also higher for girls than boys. There was furthermore a significant relation between loneliness at t1 and t2 for both genders, and this path was stronger for girls than boys. In addition, the results showed that the social classroom environment at t1 was indirectly linked to loneliness at t2 through both loneliness at t1 (β = −0.288, p < 0.001 for girls and −0.143, p < 0.001 for boys) and the social classroom environment at t1 (β = −0.364, p < 0.001 for both genders). The social classroom environment at t2 was moreover significantly and negatively related to loneliness at t2, and this path was somewhat stronger for boys than girls. Also, a greater proportion of the variance in the loneliness variable at t2 was accounted for among girls compared to boys. Finally, there were no significant direct or indirect relations between teacher support at t1 and loneliness at t2.

5 Discussion

This study has investigated the associations between first year upper secondary school students’ perceptions of teacher support, the social classroom environment and school loneliness, and how gender might moderate these relationships. First, and in accordance with hypothesis 1a), there was a positive relation between both instrumental and emotional teacher support and the social classroom environment measured at t1. By contrast, the paths from emotional and instrumental teacher support to the social classroom environment at t2 were not significant. Thus, teacher support seems to be of importance to students’ experiences of the social environment in the class, but this applies only to variables measured at the same time point. A possible explanation for the lack of significant relations between these variables across time, could be that students’ perceptions of teacher support and the social classroom environment are transient and situational experiences. Thus, the teacher support that the students experience "here and now" seems to be of greatest importance to their instant perceptions of the social classroom environment.

Girls moreover reported significantly lower levels of emotional and instrumental teacher support compared to boys, and the SEM model suggested that the two types of support had different importance to girls’ and boys’ perceptions of the social classroom environment. While for boys, instrumental teacher support was moderately related to the social classroom environment at t1, this path was not significant for girls. The relation between emotional teacher support and the social classroom environment was in turn significant for both genders, but the path was somewhat stronger for girls than boys. These results suggest that the two types of teacher support contribute differently to girls’ and boys’ experiences of the social classroom environment. While girls in this study seem to rely mainly on their perceptions of the teachers as warm and friendly, boys seem to rely more strongly on the perceived practical and formal support provided by their teachers, in addition to emotional support. Of note is also that teacher support explained a greater proportion of the variance in the social classroom environment variable among boys compared to girls. These results suggest that factors that have not been included in this study, and other than teacher support, explain the variation in girls’ scores on this variable. Future research should explore reasons for these gender differences in the relations between teacher support and the social classroom environment.

Second, and contrary to hypothesis 1b, instrumental and emotional teacher support were not directly associated with student loneliness, neither at t1 or t2. As mentioned, loneliness is a subjective and internal experience, and not the same as social isolation which might perhaps be more easily observed (e.g. Perlman and Peplau 1981, 1982). Teachers may therefore find it difficult to recognize loneliness in their students. This can in turn make it challenging for them to take concrete actions against it, for instance through providing increased social support. This lack of direct relations between teacher support and loneliness is therefore not that surprising. Although teacher support was not directly associated with student loneliness, the results showed that instrumental support was indirectly and inversely related to loneliness through the social classroom environment. These indirect associations suggest that although the teacher may not directly influence students’ feelings of loneliness at school, they can contribute to reducing it by facilitating a positive social environment in the classroom.

As could be expected, the results furthermore showed that the two types of teacher support were of different indirect importance to girls’ and boys’ loneliness experiences. First, the indirect path from instrumental teacher support to loneliness through the social classroom environment was only significant for boys. Moreover, while emotional support was indirectly and negatively associated with loneliness through the social classroom environment for both genders, this path was stronger for girls than boys. Specifically, these results indicate that both instrumental and emotional teacher support might contribute to improving boys’ perceptions of the social classroom environment, which in turn might help reduce their feelings of loneliness. For the female students, however, only emotional teacher support seems to be of importance to their perceptions of the social classroom environment, and further to their loneliness experiences. This lack of significance from instrumental support to girls' experiences of the social classroom environment and loneliness is an interesting finding that should be explored further in upcoming studies.

Next, although teacher support was significantly and indirectly related to students’ perceptions of loneliness through the social classroom environment, the strongest contributing factor to explaining students’ school loneliness was their perceptions of the social environment in the class. These findings are in keeping with hypothesis 2 and show a clear tendency that the students who have the most positive perceptions of the social classroom environment to a lesser extent experience loneliness at school. Although the importance of peer relationships to student loneliness has been widely documented in the previous literature, the results from the present study extend earlier research by showing that not only the direct relations between peers, but also the general social environment in the class seems to contribute strongly to students’ feelings of school loneliness.

The current study moreover found stronger path coefficients between the social classroom environment and loneliness than those reported in earlier studies (Cava et al. 2010, 2007; Pretty et al. 1994). One explanation for this may be differences in the operationalization of the class environment variables. Another reasonable assumption could be that the previous studies had measured students’ sense of global loneliness, whereas this study has explored loneliness specifically within the school context. It is not unexpected to find stronger relationships between variables that measure phenomena within the same context (school), as was done in the present study. The strong associations between students’ perceptions of the social classroom environment and their sense of loneliness at school moreover indicate that these are inverse, but substantially closely related phenomena.

Next, while the path between the social classroom environment and loneliness was stronger for girls at t1, the path between these variables at t2 was somewhat stronger for boys. Of note is that the indirect effects from the social classroom environment at t1 to loneliness at t2 through loneliness at t1 was stronger for girls. These results may therefore indicate that girls’ previous loneliness experiences are more important to their continued feelings of loneliness, than is the case for boys. Moreover, a larger proportion of the variance in the loneliness variables was accounted for among girls compared to boys. These findings suggest that the variation in boys’ loneliness experiences to a greater extent is explained by factors others than those included in the present study.

5.1 Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations. First, it has measured students’ perceptions of teacher support, and this does not necessarily reflect the degree of the objective or “true” support provided by the teachers. Next, although the SEM model was based on a theoretical model that specified one-directional paths between the constructs, this does not imply that causal conclusions can be drawn. Moreover, future research should include additional classroom factors that might contribute to explaining further the variation in boys’ loneliness experiences. Finally, more research is needed to explore these relationships at other grade levels.

6 Conclusion

Youth spend a great amount of time with peers and teachers in the school context, and the results from this study strongly indicate that a secure social environment is favourable to students’ psychosocial functioning. One practical implication of the research findings is that teachers ought to focus their attention on classroom practices that can facilitate a positive social environment in the class. In Norway, various state-funded school programmes aimed at improving the social climate in the school have been implemented at the upper secondary school level in recent years, such as VIP-Makkerskap [VIP Partnership]. This testifies to a growing recognition of the significance that a healthy social environment can have for students' academic and socioemotional functioning. The findings from the present study support this assumption and highlight the importance of creating and maintaining positive social relationships and a healthy social environment in school. Importantly, the study results also imply that boys and girls may benefit differently from different types of teacher support. If the assumption holds true, this is something that teachers need to become aware of in order to provide targeted social support to their students.

References

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Asher, S. R., & Wheeler, V. A. (1985). Children’s loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 500–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.500

Bakken, A. (2017). Ungdata. Nasjonale resultater 2017. NOVA-rapport 10/17. Retrieved from https://www.ungdata.no/Forskning/Publikasjoner/Nasjonale-rapporter

Bakken, A. (2018). Ungdata. Nasjonale resultater 2018. NOVA Rapport 8/18. Retrieved from https://www.ungdata.no/Forskning/Publikasjoner/Nasjonale-rapporter

Bakken, A. (2019). Ungdata. Nasjonale resultater 2019. NOVA-rapport 9/19. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12199/2252

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Benner, A. D. (2011). Latino adolescents’ loneliness, academic performance, and the buffering nature of friendships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(5), 556–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9561-2

Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00029-5

Borys, S., & Perlman, D. (1985). Gender differences in loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 11(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111006

Bru, E., Boyesen, M., Munthe, E., & Roland, E. (1998). Perceived social support at school and emotional and musculoskeletal complaints among Norwegian 8th grade students. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 42(4), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383980420402

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2012). The phenotype of loneliness. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.690510

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Crawford, E. L., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M. H., Kowalewski, R. B., et al. (2002). Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine., 64(3), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005

Cava, M. J., Musitu, G., Buelga, S., & Murgui, S. (2010). The relationships of family and classroom environments with peer relational victimization: an analysis of their gender differences. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600003747

Cava, M. J., Musitu, G., & Murgui, S. (2007). Individual and social risk factors related to overt victimization in a sample of Spanish adolescents. Psychological Reports, 101(1), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.101.1.275-290

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chipuer, H. M. (2001). Dyadic attachments and community connectedness: Links with youths’ loneliness experiences. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(4), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.1027

Cohen, J., & Steinberg, R. J. (1992). A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Danielsen, A. G., Samdal, O., Hetland, J., & Wold, B. (2009). School-related social support and students’ perceived life satisfaction. The Journal of Educational Research, 102(4), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.102.4.303-320

Ditommaso, E., & Spinner, B. (1997). Social and emotional loneliness: A re-examination of weiss’ typology of loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(3), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00204-8

Dobson, J. E., Campbell, J. N., & Dobson, R. (1987). Relationships among loneliness, perceptions of school, and grade point averages of high school juniors. The School Counsellor, 35, 143–148.

Drevets, R. K. (1996). Students’ perceptions of parents’ and teachers’ qualities of interpersonal relations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(6), 787–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537454

Federici, R. A., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2014). Students’ perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: Relations with motivational and emotional responses. International Education Studies, 7(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n1p21

Frostad, P., Pijl, S. J., & Mjaavatn, P. E. (2015). Losing all interest in school: Social participation as a predictor of the intention to leave upper secondary school early. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(1), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.904420

Galanaki, E. P., & Vassilopoulou, H. D. (2007). Teachers and children’s loneliness: A review of the literature and educational implications. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22(4), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173466

Goosby, B. J., Bellatorre, A., Walsemann, K. M., & Cheadle, J. E. (2013). Adolescent loneliness and health in early adulthood. Sociological Inquiry, 83(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12018

Hafen, C. A., Laursen, B., & DeLay, D. (2012). Transformations in friend relationships across the transition into adolescence. In A. W. Collins & B. P. Laursen (Eds.), Relationship Pathways: From Adolescence to Young Adulthood (pp. 69–89). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc.

Hair, J. F. J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited.

Harris, R. A., Qualter, P., & Robinson, S. J. (2013). Loneliness trajectories from middle childhood to pre-adolescence: Impact on perceived health and sleep disturbance. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1295–1304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.009

Haugan, J., Frostad, P., Mjaavatn, P.-E. (2019). A longitudinal study of factors predicting students’ intentions to leave upper secondary school in Norway. Social Psychology of Education 1–21 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09527-0

Hawkins-Elder, H., Milfont, T., Hammond, M. D., & Sibley, C. G. (2018). Who are the lonely? A typology of loneliness in New Zealand. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417718944

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Jamal, F., Fletcher, A., Harden, A., Wells, H., Thomas, J., & Bonell, C. (2013). The school environment and student health: a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative research. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 798–809. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-798

Katz, I., Kaplan, A., & Gueta, G. (2009). Students’ needs, teachers’ support, and motivation for doing homework: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 78(2), 246–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970903292868

Kelly, A. (1988). Gender differences in teacher–pupil interactions: a meta-analytic review. Research in Education, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/003452378803900101

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Koenig, L. J., & Abrams, R. F. (1999). Adolescent loneliness and adjustment: A focus on gender differences. In K. J. Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence (pp. 296–322). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koenig, L. J., Isaacs, A. M., & Schwartz, J. A. J. (1994). Sex differences in adolescent depression and loneliness: Why are boys lonelier if girls are more depressed? Journal of Research in Personality, 28(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1994.1004

Krause-Parello, C. A. (2008). Loneliness in the school setting. The Journal of School Nursing, 24(2), 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1622/1059-8405(2008)024[0066:LITSS]2.0.CO;2

Ladd, G. W., & Ettekal, I. (2013). Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: Normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1269–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.004

Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., Bramsen, R. H., Trillingsgaard, T., & Elklit, A. (2011). Different sources of loneliness are associated with different forms of psychopathology in adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.12.005

Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., & Elklit, A. (2011). Loneliness, Depressive Symptomatology, and Suicide Ideation in Adolescence: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9442-x

Lei, P. W., & Wu, Q. (2007). Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(3), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00099.x

Lester, L., Cross, D., Dooley, J., & Shaw, T. (2013). Bullying victimisation and adolescents: Implications for school-based intervention programs. Australian Journal of Education, 57(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113485835

Levitt, M., Guacci-Franco, N., & Levitt, J. (1994). Social support and achievement in childhood and early adolescence: A multicultural study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 15(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0193-3973(94)90013-2

Little, T. (2013). Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lodder, G. M. A., Scholte, R. H. J., Goossens, L., & Verhagen, M. (2017). Loneliness in early adolescence: Friendship quantity, friendship quality, and dyadic processes. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(5), 709–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1070352

London, B., Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Paltin, I. (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(3), 481–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x

Låftman, S. B., & Modin, B. (2012). School-performance indicators and subjective health complaints: are there gender differences? Sociology of Health & Illness, 34(4), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01395.x

Maes, M., Nelemans, S. A., Danneel, S., Fernández-Castilla, B., Van Den Noortgate, W., Goossens, L., & Vanhalst, J. (2019). Loneliness and social anxiety across childhood and adolescence: Multilevel meta-analyses of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1548–1565. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000719

Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, A., & Yarcheski, T. J. (1993). Health consequences of loneliness in adolescents. Research in Nursing & Health, 16(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770160105

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2017). Maximum likelihood estimation of structural equation models for continuous data: Standard errors and goodness of fit. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 24(3), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2016.1269606

Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstrøm, U. (2003). Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9(3), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00419.x

Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611

Parkhurst, J. T., & Hopmeyer, A. (1999). Developmental change in the sources of lonliness in childhood and adolescence: Constructing a theoretical model. In K. J. Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence (pp. 56–79). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M., & Kaplan, A. (2007). Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal Relationships: Personal Relationships in Disorder (Vol. 3, pp. 31–56). London: Academic Press.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1982). Perspectives on loneliness. In D. Perlman & L. A. Peplau (Eds.), Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy (pp. 1–18). Retrieved from https://www.peplaulab.ucla.edu/Peplau_Lab/Publications_files/Peplau_perlman_82.pdf

Pretty, G. M. H., Andrewes, L., & Collett, C. (1994). Exploring adolescents’ sense of community and its relationship to loneliness. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199410)22:4%3c346::AID-JCOP2290220407%3e3.0.CO;2-J

Rokach, A. (2016). Teachers, students and loneliness in school. In A. Rokach (Ed.), The correlates of loneliness (pp. 50–63). Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: Bentham Science Publishers.

Rotenberg, K. J., & Flood, D. (1999). Loneliness, dysphoria, dietary restraint, and eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199901)25:1%3c55::AID-EAT7%3e3.0.CO2-#

Savalei, V. (2018). On the computation of the RMSEA and CFI from the mean-and-variance corrected test statistic with nonnormal data in SEM. Multivariate behavioral research, 53(3), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1455142

Segrin, C., & Flora, J. (2000). Poor social skills are a vulnerability factor in the development of psychosocial problems. Human Communication Research, 26(3), 489–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00766.x

Segrin, C., Nevarez, N., Arroyo, A., & Harwood, J. (2012). Family of origin environment and adolescent bullying predict young adult loneliness. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.555791

Semmer, N. K., Elfering, A., Jacobshagen, N., Perrot, T., Beehr, T. A., Boos, N., & Vandenbos, G. (2008). The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.15.3.235

Sletta, O., Valås, H., & Skaalvik, E. M. (1996). Peer relations, loneliness, and self-perceptions in school-aged children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 66, 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1996.tb01210.x

Storch, E. A., Brassard, M. R., & Masia-Warner, C. L. (2003). The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescence. Child Study Journal, 33(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.003

Suldo, S. M., Friedrich, A. A., White, T., Farmer, J., Minch, D., & Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2009.12087850

Tvedt, M. S. (2017). Se videre. Et longitudinelt forskningsprosjekt om læringsmiljøets betydning for motivasjon, psykisk helse og fullføring av videregående skole. [Look ahead. A longitudinal research project on the importance of the learning environment for motivation, mental health and the completion of upper secondary school]. Retrieved from https://laringsmiljosenteret.uis.no/forskning-og-prosjekter/laringsmiljo/se-videre/

Tvedt, M.S., Bru, E., Idsøe, T. (2019). Perceived teacher support and intentions to quit upper secondary school: Direct, and indirect associations via emotional engagement and boredom. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 1–23 https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1659401

Ungdatasenteret. (2020). Hva er Ungdata? [What is Ungdata?]. Retrieved from https://www.ungdata.no/hva-er-ungdata/

Valås, H. (1999). Students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students: Peer acceptance, loneliness, self-esteem, and depression. Social Psychology of Education, 3(3), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009626828789

Vanhalst, J., Klimstra, T. A., Luyckx, K., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Goossens, L. (2012). The interplay of loneliness and depressive symptoms across adolescence: Exploring the role of personality traits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(6), 776–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9726-7

Vanhalst, J., Luyckx, K., & Goossens, L. (2014). Experiencing loneliness in adolescence: A matter of individual characteristics, negative peer experiences, or both? Social Development, 23(1), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12019

Vanhalst, J., Luyckx, K., Scholte, R., Engels, R., & Goossens, L. (2013). Low self-esteem as a risk factor for loneliness in adolescence: Perceived - but not actual - social acceptance as an underlying mechanism. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(7), 1067–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9751-y

VIP School Programme. (2015). «Man har alltid noen å sitte med slik at ingen føler seg utenfor». Evalueringsrapport VIP-makkerskap—Et skolestartstiltak for bedre læringsmiljø [VIP Partnership evaluation report]. Akershus: Vestre Viken.

VIP School Programme. (2016). En plass for alle. Evalueringsrapport VIP-makkerskap [A place for everyone- VIP Partnership evaluation report]. Akershus: Vestre Viken.

Watson, J., & Nesdale, D. (2012). Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 1984–2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00927.x

Wentzel, K. R., Battle, A., Russell, S. L., & Looney, L. B. (2010). Social supports from teachers and peers as predictors of academic and social motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35(3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.03.002

Woodhouse, S. S., Dykas, M. J., & Cassidy, J. (2012). Loneliness and peer relations in adolescence. Social Development, 21(2), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00611.x

Wu, A., & D., Li, Z., & Zumbo, B., D. . (2007). Decoding the meaning of factorial invariance and updating the practice of multi-group confirmatory factor analysis: A demonstration with TIMSS data. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.7275/mhqa-cd89

Wyrick, A. J. (2011). Teacher-student relationships during adolescence: The role of parental involvement, behavioral characteristics, gender, and income (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1599

Funding

Open Access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares to have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by The Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morin, A.H. Teacher support and the social classroom environment as predictors of student loneliness. Soc Psychol Educ 23, 1687–1707 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09600-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09600-z