Abstract

This paper focuses on an unexamined area of trade—the behaviour of heterogeneous intermediate suppliers facing final producers of different ability and pursuing different strategies. To inform our empirical analysis, we develop a theoretical model to analyse the choice of an intermediate supplier between selling to domestic producers, selling to multinational producers and/or exporting to foreign producers. The model’s predictions are: (i) sufficiently productive firms self-select into supplying to multinationals or exporting, while the most productive firms pursue both strategies, and (ii) the order of preferred strategies between supplying to multinationals and exporting depends on foreign direct investment inflows and export set-up costs. The paper uses firm-level data with rare information about multinational suppliers from 29 countries in Europe and Central Asia in 2002 and 2005 to test these theoretical predictions. The empirical analysis confirms both of our model’s predictions. Moreover, it suggests that multinational suppliers are more likely to have higher required levels of ex-ante labour productivity than exporters, implying that exporting is easier and a more popular choice for firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Not all firms are the same in terms of ability and their sales destinations. With regards to final goods producers, it is well established that firm productivity positively correlates with market entry and that more productive firms self-select into exporting and investing in production abroad (Bernard and Jensen 1999; Melitz 2003; Helpman et al. 2004). Intermediate goods suppliers also face a choice between exporting to foreign markets and supplying the domestic market. However, the choices facing an intermediate supplier go beyond this basic one and are more complex given the fact that it trades with final goods producers of different abilities and with different strategies, even within the same market. In this context, it is natural to inquire into whether firms supplying foreign final producers are different from firms supplying domestic final producers. Due to paucity of data on firm-level intermediate goods trade, there has been a limited number of studies looking into this issue both empirically and theoretically. Given the development of multinationals and their global value chains and the fact that trade in intermediate inputs represents an increasingly dominant share in total trade flows, we believe that this area of research deserves more research attention.

This paper extends the analysis of firm heterogeneity based on the Melitz (2003) framework to the intermediate sector, and develops a theoretical model to explore the behaviour of the intermediate goods suppliers and the final goods producers simultaneously. Our model analyses the behaviour of intermediate goods suppliers in response to three types of final producers that are differentiated by their productivity and their corresponding supply destinations, namely, domestic final producers, foreign final producers and multinationals. The characteristics of intermediate suppliers to multinationals relative to those of exporting intermediate suppliers are particularly interesting given that supplying multinational subsidiaries in the domestic market can be considered as an alternative strategy to exporting.

The first question we address is whether there is self-selection of more productive suppliers to gain contracts with multinationals and foreign final producers. Our model predicts that less productive suppliers only sell to the domestic-oriented final producers, more productive suppliers self-select into supplying multinationals or exporting and the most productive firms pursue both supplying strategies. Intermediate suppliers face higher fixed costs to enter a foreign market or to gain a contract with multinationals than to supply domestic final goods producers. Hence, only more productive intermediate goods suppliers are able to be profitable and survive in the multinational and foreign markets.

The second prediction of our model concerns the comparison between multinational suppliers and exporting suppliers. On the one hand, it might be easier for an intermediate supplier to sell to multinational subsidiaries in the local market than to export, because it can save on marketing and distribution set-up costs in the foreign market. On the other hand, supplying multinationals can be challenging since only a small number of firms with top productivity levels become multinationals (Helpman et al. 2004) and the chance to gain a contract with them is limited. Furthermore, it is plausible that multinationals have specific expectations and requirements with regards to their suppliers, as they tend to possess high level of technology and management skills. This implies that suppliers to multinationals must have special characteristics that allow them to be chosen. Differences, therefore, may exist between an exporting supplier and a multinational supplier.

In our model, an intermediate supplier’s choice between the two strategies—supplying multinationals and exporting—is determined by its own productivity, the productivity of its potential customers and market characteristics. A change in trade or investment costs will affect an intermediate supplier’s relative preference for these two choices. In particular, relatively lower trade costs make the export strategy more popular, while relatively low investment costs and, consequently, relatively higher FDI inflows make supplying multinationals more favourable.

Using a firm-level dataset with rare information on intermediate suppliers for 29 European and Central Asian countries in 2002 and 2005, our paper then tests these theoretical predictions about suppliers’ preferences and choices. We find strong empirical support for our theoretical predictions. Specifically, in relation to the first prediction, multinational suppliers and exporting suppliers have higher ex-ante productivity levels, are larger and invest more compared to domestic-oriented intermediate suppliers, while the most productive firms become both exporters and multinational suppliers. Compared to exporting firms, multinational suppliers are found to be relatively younger, smaller, more productive and pay higher labour wages. In accordance with the second prediction of our model, the empirical results show that the probability of choosing a certain strategy changes according to trade and investment conditions. In particular, the countries in our sample are generally characterised by relatively high investment costs and low foreign investment inflows, albeit in different magnitudes. Such features, potentially due to these countries’ institutional characteristics at the time, imply that multinational suppliers tend to have higher required levels of ex-ante labour productivity than exporters, which makes exporting easier and a more popular choice for firms in our sample. Moreover, our results are robust to potential endogeneity issues due to learning effects.

Our paper is closely related to the literature on heterogeneous firms’ behaviour and the self-selection of more productive firms into exporting (Bernard and Jensen 1999; Melitz 2003) and investing abroad (Helpman et al. 2004). This literature shows that firm productivity correlates with the number of export markets that a firm serves (Eaton et al. 2011; Lawless 2009; Wagner 2012) and the difficulty to enter an export market (Melitz and Ottaviano 2008; Chaney 2008; Serti et al. 2010). This is due to the fact that firms need to be more productive to cover the extra costs of entering more demanding or more distant foreign markets. More recent work also shows that there is self-selection of firms based on productivity and innovativeness into different internationalization modes, including indirect exports, direct exports, outsourcing, service FDI and manufacturing FDI (Bekes and Murakozy 2018).

We contribute to this literature by focusing on intermediate goods suppliers’ behaviour and providing a framework to analyse the impact of trade liberalization and investment liberalization together with firms’ behaviour in both final goods and intermediate goods sectors. We show that exporting is not always the ultimate choice for highly productive firms. It is not rare to find in our data a productive firm choosing to supply multinationals only as opposed to exporting. We also analyse the factors, including host country’s characteristics and firms’ characteristics, that influence firms’ choice between supplying multinationals, exporting and pursuing both strategies.

Several theoretical models have incorporated an intermediate sector to explain the input sourcing behaviour of final goods producers in international trade. In particular, Antras and Helpman (2004) study multinationals’ outsourcing decision and the characteristics of the host economy. Amiti and Konings (2007), Kasahara and Rodrigue (2008) and Halpern et al. (2015) look at firms’ importing input decision to find that foreign-oriented firms (i.e., multinationals or exporters) tend to import more foreign inputs compared to their domestic-oriented peers. These strands of the literature, however, focus on the strategy of the final goods producers and treat intermediate suppliers homogeneously. Thus, these papers can explain the variation in input sourcing behaviour of final producers across countries, but they cannot explain such variation within a country. In reality, not all local suppliers can export or supply their intermediate products to multinationals and the fraction of the foreign-oriented intermediate suppliers is small.

More recently, a few theoretical studies have started to explore the heterogeneity in the behaviour of suppliers in serving multinationals. Lin and Saggi (2007) and Carluccio and Fally (2013) suggest that only some suppliers switch to new technologies to supply exclusively to multinationals, while the rest do not. In these studies, intermediate suppliers are, however, homogeneous and the driving force of their different choices does not come from their own ability but depends on either the size of the technology transfer they would get or the size of the multinational presence. Thus, we provide a contribution to this literature, which has not explored whether certain suppliers are more likely to choose to become multinational suppliers based on their specific ex-ante characteristics.

Another strand of the international trade literature closely linked to this paper is the one looking at FDI’s backward spillover effects on domestic intermediate suppliers. In this literature, FDI and serving multinational affiliates are often claimed to provide several benefits, including technology transfers and productivity improvements for domestic suppliers (Blomstrom and Kokko 1998; Javorcik 2004). There have been abundant empirical studies with mixed results, yet, there has been a limited theoretic base supporting these claims. Major theoretical works in this field suggest that the entry of multinationals raises the demand for intermediate products by domestic suppliers but do not look at the possibility of productivity improvements for suppliers or the mechanism through which the spillover effect may occur (Markusen and Venables 1999). While the empirical evidence on FDI spillovers is non-conclusive (Meyer and Sinani 2009), there is some empirical evidence for a positive association between the extent of FDI spillovers and firms’ absorptive capacity. Blalock and Gertler (2009) show that firms that invest in R&D and have a higher percentage of educated labour force benefit more from a higher multinational presence in the case of Indonesia. Keller and Yeaple (2009) show that relatively high productivity is required for a firm to benefit from FDI spillovers in the case of the United States. Similarly, Nicolini and Resmini (2010) find that only more productive firms are able to reap the technological externalities emanating from FDI in the case of Bulgaria, Romania and Poland. However, little is known about whether the positive correlation is due to spillovers from multinationals or there is self-selection of more productive suppliers gaining a contract with multinationals.

Recent case studies also provide similar observations about the relationship between suppliers and multinationals. Javorcik and Spatareanu (2005) show that it is more common that multinationals “cherry pick” better performing suppliers and local suppliers actively upgrade their production technology to gain a contract with multinationals. Godart and Gorg (2013) show that only firms that experience pressure from their multinational customers have positive productivity growth after supplying multinationals. These results are in contrast with the often claimed “technology transfer” or “learning-by-doing” effects on local suppliers due to the presence of multinationals. Javorcik and Spatareanu (2009) is the only study taking into account the self-selection of more productive firms into supplying multinationals in estimating the FDI spillovers.

Our contribution to this field is to provides a theoretical base and empirical evidence for the self-selection of more productive suppliers able to gain contracts with multinationals. Compared to Javorcik and Spatareanu (2009), who use a small sample of 108 firms in the Czech Republic, we use a larger sample of more than 12,000 firms in 29 countries. This multi-country sample does not only provide further evidence for the exceptional characteristics of multinational suppliers on a larger scale but also allows us to analyse the influence of home countries’ characteristics on firms’ preferences for different supply strategies. Thus, our findings may help to explain the vast differences in the extent of FDI spillovers across different studies using data from countries with different characteristics.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the analytical model, focusing on the input sourcing behaviour and the behaviour of the corresponding intermediate suppliers. It also analyses how a reduction in trade costs or investment costs would affect the behaviour of both intermediate goods suppliers and final goods producers. Section 3 presents the data and some preliminary analysis, while Sect. 4 presents the regression analysis. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the findings of this paper.

2 Model

The model considers a world with two symmetric countries. In each country, a continuum of firms engage in two sectors, namely, production of a final good and production of an intermediate good. An individual firm either produces the final good, for which it is called a final producer, or produces the intermediate good, for which it is called a supplier, but does not engage in both sectors. Each firm produces a differentiated variety of the good so it faces monopolistic competition in either sector. A final good variety is produced using labour and a composition of intermediate good varieties that can be sourced from different suppliers.

Both final producers and suppliers draw their productivity randomly from a productivity distribution before choosing their strategy and pay the corresponding fixed entry costs. A final producer can choose to set up its production in the home country or in the foreign country via foreign direct investment (FDI) or both. In the latter case, that final producer is labelled as a multinational. Firms’ decisions to set up their production in the domestic market or in the foreign country solely depend on its profitability in each market, which depends on productivity and the fixed costs. All surviving final producers sell to the domestic market. Doing FDI is a strategy to earn extra profits from the foreign market for the sufficiently productive final producers.Footnote 1 Intermediate goods are tradable between the two countries. In all cases, a final producer in either country can source its inputs from both domestic intermediate suppliers and foreign intermediate goods suppliers via importing.

The model shares features with Helpman et al. (2004) in the consumer’s preference structure, assumed to be a standard Dixit-Stiglitz constant elasticity of substitution, and the final good sector, where a final producer pays a fixed entry cost that varies depending on whether it chooses to produce locally or set up production in the other country (FDI activity).

The main feature that distinguishes our model from Helpman et al. (2004) is related to the input sourcing behaviour of the final producers and the corresponding behaviour of heterogeneous suppliers when facing final producers that pursue different strategies. In the intermediate good sector, a supplier faces three mutually non-exclusive strategies, i.e., (i) serving domestic final producers, (ii) exporting to final producers in the foreign country, and (iii) supplying multinationals in the domestic country. Different fixed entry costs are required to pursue each strategy. The fixed cost to export and to supply multinationals are assumed to be higher than the entry cost to the domestic market. However, the fixed cost to export can be higher or lower than the fixed cost for a local supplier to enter a contract with a multinational.Footnote 2 Each supplier then makes its choice knowing its productivity, the different entry costs of each strategy and the demand for intermediate goods from each group of final producers. As a clarification, firms’ types and choices are presented in Table 1.

Given the above setup, we note the following propositions describing the suppliers’ behaviour, for which we provide proofs in “Appendix 1” together with the mathematical specification of the model.Footnote 3

Proposition 1

Both exporting suppliers and multinational suppliers have higher productivity cutoffs than domestic-oriented suppliers.

This proposition says that higher productivity is required to become a multinational supplier or an exporter than to become a domestic-oriented supplier. Thus, both suppliers to multinationals and exporting suppliers are more productive than the domestic-oriented suppliers. Intuitively, a supplier has to be more productive to cover the higher fixed entry costs to export and to supply multinationals. Furthermore, there are fewer multinationals than firms of other types and, hence, it is more competitive to gain a contract with a multinational and only more productive suppliers can succeed in such competition.

Proposition 2

Depending on relative entry costs, suppliers to foreign final producers (exporting suppliers) can be either more or less productive than suppliers to multinationals.

-

(i)

If transportation costs and fixed entry costs to export are sufficiently low relative to investment costs, the productivity cutoff to supply multinationals is higher than the productivity cutoff to export.

-

(ii)

If transportation costs and fixed entry costs to export are sufficiently high relative to investment costs, the productivity cutoff to export is higher than the productivity cutoff to supply multinationals.

Since exporting and supplying multinationals are distinct options for a foreign-oriented supplier, it is interesting to know the characteristics that differentiate these two types of suppliers. Proposition 2 sets the ground for the two scenarios that will be discussed in the empirical section.

The first scenario, as reflected in Proposition 2(i), represents a low trade costs/high investment costs country where becoming an exporter is easier than becoming a multinational supplier, thus making the strategy to supply multinationals only a non-preferred choice for suppliers. The second scenario, as reflected in Proposition 2(ii), represents a high trade costs/low investment costs country, where becoming an exporter is more difficult than becoming a multinational supplier, thus, making exporting only a non-preferred option for suppliers.

These two scenarios are determined by the ratio of multinationals’ sales in a country to export sales to the foreign country, that is, the ratio between FDI flows and the size of the foreign market. Intuitively, a high cost to set up multinational production results in a small number of multinationals in each country, and therefore, suppliers have to be more productive to compete for a place in the multinational market. Only when the multinational set-up cost is relatively low, and hence, there is a large mass of multinationals, does the productivity cutoff to supply multinationals become lower than the productivity cutoff to export.

Proposition 1 suggests that there is a rank in the average productiveness across different types of suppliers and productivity is a predictor for firms’ preferred choice of strategy. Specifically, the least productive suppliers serve the domestic market only, more productive suppliers serve the domestic market and either export of supply multinationals, and the top productive suppliers serve all the markets. Proposition 2 suggests that a change in trade or investment conditions can affect the order of preferred strategies for a supplier. In particular, an increase in trade costs or a decrease in investment costs will make a supplier more likely to choose to supply multinationals and less likely to export.

3 Data and preliminary analysis

This section will firstly describe the data, and then provide an exploratory analysis to examine if firms have different characteristics that influence their choices of strategy as predicted in Proposition 1 and Proposition 2 of our theoretical model. In particular, these propositions establish that more productive suppliers either export or supply multinationals, the top productive suppliers pursue both strategies, while the least productive suppliers sell to domestic final producers only. The distinction between exporting suppliers and multinational suppliers depends on fixed trade costs relative to fixed investment costs.

3.1 Data

Data on firm performance and sales destinations are taken from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS), which was jointly collected by the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. BEEPS is composed of both repeated cross-sectional datasets and a panel dataset, which include information on the characteristics of firms located in 29 European and Central Asian countries for years 2002, 2005 and 2009.Footnote 4 Data for GDP, export costs, investment costs, FDI flows and exchange rates for all countries are taken from the World Bank’s country database.

The BEEPS survey covers all manufacturing sectors and the construction, services, and transport, storage and communications sectors. The establishments included in BEEPS are defined as commercial, service or industrial business establishments and have at least five full-time employees. While the panel dataset BEEPS 2002–2009 contains information about firms’ performance in each surveyed year and three years prior to each survey, it does not contain specific information on firms’ domestic sales. Such information is only included in the 2002 and 2005 cross-sectional surveys due to differences in the questionnaire used in the 2008/2009 survey round. Our dataset is, thus, constructed by merging two cross-sectional datasets, BEEPS 2002 and BEEPS 2005, containing information on firms’ sales composition into the main panel dataset, BEEPS 2002–2009, using for each round the identification code at the establishment level.

Our sample is limited to 12,010 observations covering the years 2002 and 2005 and including firms with non-missing information for firms’ age, total sales, labour force, export sales and sales to multinationals. Data on sales, components of sales, fixed assets, operating cost, labour cost, R&D investment and other costs denominated in local currencies are converted into US dollars using the corresponding exchange rates in 2002 and 2005 for consistent comparison. Given the small number of firms that were interviewed and recorded in both years, the dataset is made up of a pooled cross-sectional sample. The first sample includes 4536 observations for 2002 and the second sample includes 7474 observations for 2005. The 2005 sample will be used for the main analysis using the multinomial probit model, while the 2002 sample is used as a robustness check.Footnote 5 In addition, we use a subsample of 4497 firms with non-missing information for 2005 on wages, investment, marketing expenditures and R&D expenditures in 2005 to estimate firms’ premia as well as a subsample of 1128 firms interviewed in both 2002 and 2005 with information on lagged supply status to check that our results are not driven by learning effects.Footnote 6

The survey data provide firms’ shares of sales to multinationals, parent firms, governments, state-owned enterprises, large domestic firms (with more than 250 employees) and individuals and small domestic firms, which altogether make up one hundred percent of each firm’s total sales. Firms with positive sales to multinationals, large domestic firms, parent firms or state-owned enterprises account for 56.8% of the total number of firms, while there are 43.3% of firms selling all their output to small domestic firms and individuals. There is, however, no further breakdown of the share of sales to this group into small domestic firms and individuals separately.

Firms are divided into four categories according to two activities, exporting and supplying multinationals. An exporter is defined as a firm whose direct export sales account for a positive share of total sales of the firm.Footnote 7 A multinational supplier (MNC supplier) is defined as a firm whose share of sales going to multinational customers is positive. Table 2 provides a frequency table for each category by year. It can be seen that exporters account for nearly 23–24% of the total number of firms in each year, while only 14% of firms supply to multinationals in the host countries.

Table 3 provides a summary statistics of key variables, i.e., log of output sales (\(\ln Y\)), log of labour employed (\(\ln L\)), and log of labour productivity (\(\ln LP\)), which is calculated as the ratio of total sales over total permanent labour.

The summary statistics reveal that firms that export (category 2) tend to have higher sales and larger scale (in term of labour force) than firms that serve the domestic market or multinationals. Firms that supply multinational customers (category 1) also have larger sales and larger scale than firms that serve only domestic customers (category 0). Both exporting firms and multinational-supplying firms have distinctively higher labour productivity than firms that serve only domestic customers.

Across the four categories, firms that participate in both activities, i.e., exporting and supplying multinationals (category 3), have the largest sales and highest labour productivity on average, whereas firms that neither export nor supply multinationals tend to have the smallest sales and lowest labour productivity.

As discussed in the theoretical part, the export market and multinational markets may be more demanding and require higher product and delivery standards. A supplier, therefore, needs to make deliberate investment efforts to enter the export and multinational markets. These efforts may include investigating the new market’s tastes and requirements as well as actively advertising products to the new potential customers. The marketing cost and investment to upgrade production to the required standards are parts of the fixed entry costs to enter the new market and should therefore be higher for firms in categories 1, 2 and 3. Table 4 provides the summary statistics of the variables that are used as proxies for firms’ deliberate investment efforts to enter the new markets. The variables Wages, Investment, Operating, Marketing and \(R \& D\) represent, respectively, firms’ average wages, new investment in fixed assets, operating costs, marketing and advertisement costs and R&D expenditures.

It can be seen from the above summary statistics that exporters and suppliers to multinationals tend to pay higher wages, spend more on new fixed assets, operating costs and marketing and advertisement activities, and invest more in R&D. The average values of investment in R&D, total investment, operating costs, marketing costs and average wages paid to workers are highest for firms participating in both activities, followed by firms exporting only, then firms supplying multinationals and finally firms not participating in neither activity.

3.2 Comparison of productivity distributions

As a preliminary test of the model’s predictions, we use the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to compare the productivity distributions across different groups of suppliers, i.e., domestic-oriented suppliers, multinational suppliers, exporters and suppliers that both export and serve multinationals. Differences in labour productivity levels across different categories of suppliers can reflect self-selection effects but may also reflect the improvement of firms’ performance after choosing a certain strategy, i.e., the learning effects discussed in the introduction. In order to separate the learning effects from self-selection effects, we focus on the ex-ante characteristics of firms that influence firms’ choice of supply strategy.

The comparisons are carried out for the log of ex-ante labour productivity (\(\ln LP_{-3}\)) in both 2002 and 2005, where the ex-ante labour productivity is calculated as the ratio of total sales over total permanent labour at time \(t-3\).Footnote 8 The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test only makes it possible to compare two distributions at a time, so distinct tests for the five pairs of categories are run: domestic-oriented suppliers versus multinational suppliers and exporters, firms that both export and supply multinationals versus firms that either export or supply multinationals, and finally, exporters versus suppliers to multinationals.Footnote 9

The test statistics are presented in Table 5. Following Delgado et al. (2002), for each pair of firm categories, we report the test statistics for the two-sided test, which determines if the two groups come from the same distribution, and the one-sided test, which determines if the first group contains smaller values than the second group. When the two-sided test is rejected (p-values lower than 0.05) and the one-sided test cannot be rejected (p-values greater than 0.05), it suggests that the first distribution is to the right of the second distribution. Based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test results, it can be confirmed that both exporting suppliers and multinational suppliers are significantly different from domestic-oriented firms and the two former groups tend to have higher level of ex-ante labour productivity compared the latter group. On the other hand, firms that engage in both activities are significantly different from firms supplying multinationals only or exporting only.

When one compares the ex-ante labour productivity distributions of exporters and multinational suppliers, however, it is not possible to reject the null hypothesis that the two groups of firms come from the same distribution.

3.3 Exporters’ and multinational suppliers’ premia

To explore whether firms that export and/or supply multinationals have different characteristics from firms that engage in neither of those two activities, we follow Bernard and Jensen (1999) and estimate exporters’ and multinational suppliers’ premia for different firms’ characteristics. The specification used is given by

where \(X_{i}\) are firm i’s characteristics, MNC \(supplier_{i}\) is a dummy equal to 1 if firm i supplies to multinationals but does not export, \(Exporter_{i}\) is a dummy equal to 1 if firm i exports but does not supply multinationals, and \(Both_{i}\) is a dummy indicating whether firm i engages in both activities. The coefficients \(\beta _{m}\), \(\beta _{x}\) and \(\beta _{mx}\), therefore, measure the difference in the characteristics between multinational suppliers, exporters and firms doing both activities compared to domestic-oriented suppliers, the omitted category. Size dummies (in terms of labour employment), sector dummies and country dummies are also included to control for other factors that could affect firms’ characteristics.

Based on the available data, the characteristics examined include firms’ ex-ante labour productivity \((LP_{-3})\), average wages (Wages), investment in new equipment and machinery (Investment), marketing costs (Marketing) and R&D spending \((R \& D).\)

The regressions for these five characteristics are run in parallel using the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) estimator via Maximum Likelihood on the 2005 sample. SUR takes into account the possible correlation across the error terms from the five regressions. The estimation results and the Wald tests for the differences in the coefficients for each regression are reported in Table 6.

The results show that all characteristics (ex-ante labour productivity, labour wages, investment, marketing costs and R&D investment) are significantly higher for firms engaged in exporting or supplying multinationals or both compared to firms that neither export nor supply multinationals. The test results for differences across the three firm categories (\(\beta _{m}\), \(\beta _{x}\) and \(\beta _{mx}\)) are all statistically significant. In particular, firms engaged in both exporting and supplying multinationals tend to have higher ex-ante labour productivity, higher investment and marketing expenses and pay higher wages than exporting firms. Multinational suppliers also tend to have higher ex-ante labour productivity and pay higher wages than exporters. On the other hand, exporters and firms engaged in both activities tend to spend more on R&D than multinational suppliers.

These preliminary results are in line with Proposition 1 of the theoretical model suggesting that exporters and multinational suppliers are more productive than domestic-oriented suppliers. Notably, the estimate for \(\beta _{m}\) is higher than and significantly different from \(\beta _{x}\), suggesting that multinational suppliers tend to have significantly higher ex-ante labour productivity compared to exporters. The estimate for \(\beta _{m}\) is also higher than \(\beta _{mx}\), though the difference is not statistically significant. These results seem to be aligned with scenario (ii) of Proposition 2, where the productivity cutoff of multinational suppliers is equal to the productivity cutoff of firms engaged in both activities and higher than the productivity cutoff to export.

The test results also show consistent evidence in support of our assumption about the fixed entry costs to each market. It is revealed that exporting firms, multinational suppliers as well as firms doing both activities have significantly higher marketing costs than firms doing neither activity, as indicated by the coefficients on marketing costs. Compared to multinational suppliers, exporters tend to spend more on marketing activities, though the difference is insignificant. It is possible that, in order to supply multinational customers, local suppliers may have to carry out different marketing activities or set up different distribution channels from their domestic practices, hence the costs are comparable to the entry cost to a foreign market. It can be noted that, according to our model, the closer these two entry costs are, the higher the likelihood that Scenario (i) of Proposition 2 would occur, suggesting that exporting is an easier choice for suppliers than supplying multinationals.

As inferred from Proposition 2, exporters would be more or less productive than multinational suppliers depending on the ratio of FDI inflows to market size and set-up costs to export. These characteristics may vary across countries and sectors. This motivates us to analyse how different characteristics of countries and sectors may affect intermediate firms’ choices with regards to the way they supply final producers.

4 Empirical analysis

The preliminary analysis has provided support for our predictions about the superior characteristics of multinational suppliers, exporters and firms doing both activities. The aim of this section is to analyse more formally the conditions under which firms would choose a particular strategy over the others and if their behaviour would change in response to trade and investment costs as predicted in Proposition 1 and Proposition 2. In particular, a reduction of fixed investment costs encourages suppliers to become multinational suppliers, whereas they prefer exporting over supplying multinationals under a liberalised trade regime.

4.1 Multinomial probability specification

To analyse firms’ choices over alternative supplying strategies, exporter, multinational supplier, neither or both, the multinomial probit (MNP) model is employed.Footnote 10 Consider firm i choosing one alternative among a set of four alternatives \(k=0,1,2\) and 3: multinational supplier but not exporter \((k=1)\), exporter but not multinational supplier \((k=2)\), both multinational supplier and exporter \((k=3)\), and neither multinational supplier nor exporter \((k=0)\), i.e., the firm only sells to domestic customers. Option 0 will be used as the base outcome in our estimations.

These four options are mutually exclusive and exhaustive for firms. Firm i’s decision to choose type k depends on its profits, which are a function of its ex-ante labour productivity, the ratio of FDI inflows over the market size, the sunk costs to export and to supply multinational affiliates and possibly other firm-specific, sector-specific and country-specific factors. The profit function can be written as

where \(U_{ik}\) is the profit of firm i with strategy k, covariates \(X_{i}\) include other firms’ characteristics, covariates \(Z_{i}\) control for country and sector characteristics that might influence the decision of firm i, and \(\varepsilon _{ik}\) captures other unobserved factors that affect firm i’s profits. To maximise profits, firm i chooses type k such that its profit \(U_{ik}\) is maximised. The probability that firm i chooses type k, therefore, is:

Vector \(X_{i}\) includes firms’ specific characteristics other than their ex-ante labour productivity, such that

where \(\ln L_{-3,i}\) is the logarithm of a firm’s labour force at time \(t-3\), \(\ln Age_{i}\) is the logarithm of firm’s age, and \(FR_{i}\) is a dummy variable equal to 1 if firm i has foreign-owned shares. The reason to include these controls is that larger and more experienced firms and firms with foreign ownership tend to be more able to pay for the fixed entry costs and, thus, have a greater advantage in exporting or supplying multinational customers.

Depending on the variables included in vector \(Z_{i}\), which controls for sector- and country-specific characteristics, we have two specifications, M1 and M2. Specification M1 is given by:

where

In specification M1, we control for country and sector characteristics by including country dummies and sector dummies. While firms are grouped in eight sectors in the original dataset, some sectors have too few observations, so firms are regrouped into five larger sectors. The 5 major sectors are: construction \(\left( s1\right)\), manufacturing and mining \(\left( s2\right)\), real estate, hotel and business service \(\left( s3\right)\), wholesale and retail \(\left( s4\right)\) and other services \(\left( s5\right)\).

Specification M2 is given by:

where

In specification M2, country dummies are dropped while country-specific characteristics are added. In particular, we include \(\ln GDP\) to control for countries’ demand, \(\ln EXCOST\) to control for the sunk costs to export, and \(\ln \left( FDI/GDP\right)\) to control for the foreign direct investment activities in the home country.

\(\ln GDP\) is the logarithm of the home country’s GDP (denominated in US dollars). \(\ln EXCOST\) is the logarithm of the average number of documents that a firm needs to complete in order to export and, thus, a proxy for the sunk costs to export. The idea is that the higher the number of documents needed the more obstacles there are and the longer the preparation procedures for exporting and, thus, the higher the cost to export. In our sensitivity analysis, other proxies for export sunk costs are used, including the average time necessary to comply with all procedures required to export goods and the average time to clear exports through customs. \(\ln \left( FDI/GDP\right)\) is the logarithm of the ratio of FDI inflows into the home country over the GDP of the rest of the world (i.e., world GDP minus the home country GDP, in short RoW GDP). This is a proxy for the term \(\frac{\int _{\varphi ^{M}} \varphi ^{\theta -1}dG\left( \varphi \right) }{\int _{\varphi ^{D}} \varphi ^{\theta -1}dG\left( \varphi \right) }\) given by Eq. (32) in the theoretical model in “Appendix 1”, where the foreign country is now the rest of the world. In the sensitivity analysis, we also use other proxies for the sunk costs to set up multinational subsidiaries in the home country, including the average time required to start a business, the average number of start-up procedures to register a business and the corporate tax rate in the home country.

To explore how these country- and sector-specific characteristics influence the marginal effect of labour productivity on firms’ behaviour, the interaction terms between these variables and labour productivity are also included. Since the data on FDI and export costs are available at country level, it is not possible to analyse these effects at the sectoral level. Instead, interaction terms between ex-ante labour productivity and sector dummies are added to explore the heterogeneous impacts of sectoral characteristics on the marginal effect of labour productivity. There are, hence, three interaction terms between \(\ln LP_{-3,i}\) and \(\ln GDP\), \(\ln EXCOST\) and \(\ln \left( FDI/GDP\right)\), and four interaction terms between \(\ln LP_{-3,i}\) and the four sector dummies included in our specification.

4.2 Estimation results

The empirical results presented in this section are estimated using the BEEPS 2005 sample, while the BEEPS 2002 sample is used as a robustness check (results are available upon request). Results of the MNP estimation are presented in Table 9 of “Appendix 3”. In this section, we focus on the marginal effects, which are more readily interpreted. Given the large number of categorical variables, the marginal effects are calculated for a domestic-owned firm in the manufacturing sector—the largest sector in our sample accounting for 34% of observations—while other variables are set at their means, unless otherwise indicated.

Labour productivity, firm characteristics and choice of firm type Table 7 presents and compares the marginal effects of labour productivity and of other firm characteristics on the probability of each outcome estimated for the two specifications M1 and M2.

After controlling for all other factors, the marginal effects of labour productivity on the probabilities of each outcome shown relative to the outcome of supplying domestic firms are significant at the 1% level. The estimates show that a small increase in ex-ante labour productivity at the mean would increase the probability of supplying multinationals by 1.8 to 2.4 percentage points (pp), depending on the model specification, the probability of exporting by 3.7 to 3.9pp, and the probability of doing both activities by 1.9 to 2.4pp. These results suggest that firms use different supplying strategies depending on their ex-ante labour productivity. In particular, more productive firms self-select into supplying multinationals and exporting. This is consistent evidence in favour of Proposition 1 of our model.

The marginal effects of other firm-specific characteristics, in particular firms’ size, age and foreign ownership, on the probability of each outcome are also positive and significant. It can be seen that when ex-ante firms’ size increases, the probability of supplying multinationals increases slightly, while the probability of exporting increases the most. This evidence suggests that larger firms are more likely to export as opposed to supplying multinationals. Firms with foreign-owned shares significantly improve their chance to become exporters or both. In particular, having foreign ownership increases the probability of exporting by up to 18pp. It is possible that managers of firms with foreign-owned shares have more experience with foreign markets, which, in turn, makes it easier to start exporting. We explore further the effects of foreign ownership in “Appendix 9”.Footnote 11 The analysis in “Appendix 9” shows that, as firms become more productive, having foreign ownership lowers the probability of supplying to multinationals for all levels of labour productivity. However, having foreign ownership increases the probability of exporting for firms with low to average labour productivity levels and lowers the probability of exporting only for high productive firms. Across all levels of labour productivity, having foreign ownership increases the probability of both supplying multinationals and exporting. Firms’ age, on the other hand, tends to be an insignificant determinant of firms’ choice in our case. The marginal effects are only significant for the probability of exporting, but not in a robust way.

In order to analyse whether productivity determines the rank of firms’ preferred strategies as predicted in Sect. 2.5, we estimate the marginal effects of ex-ante labour productivity on the probabilities of each outcome as firms’ ex-ante labour productivity changes across its distribution. The marginal effects are again estimated for a domestic manufacturing firm in an economy of average GDP size, with average FDI inflows and average export fixed costs.

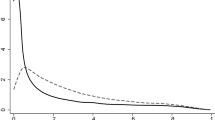

Figure 1 depicts these marginal effects and their significance. It shows that firms’ choice of type differs significantly across the distribution of labour productivity. As labour productivity increases for firms with labour productivity up to the 50th percentile, the probabilities of supplying multinationals, exporting and doing both activities increase. Clearly, this implies that the probability of doing neither activity decreases considerably. Moreover, the marginal effects of labour productivity on the probability of exporting are considerably higher than those on the probability of supplying multinationals. This implies that exporting would be the preferred choice compared to supplying multinationals when firms’ labour productivity is lower than or close to that of the median firm. These results are consistent with the low trade costs/high investment costs scenario described in Proposition 2(i) of our model. In this case, supplying multinationals is associated with a higher productivity cutoff compared to exporting, which results in exporting being the more popular choice for lower values of labour productivity.

As labour productivity continues to increase to the top of the productivity distribution, the probabilities of either exporting or supplying multinationals decrease and become less significant, while the probability of firms doing both activities rises up significantly, surpassing the probability of doing either activity separately. For the top 5% of firms in terms of labour productivity, the probability of doing both activities is at its highest level while the probability of doing either activity separately is lower or even turns insignificant. The fact that the most productive firms tend to be both multinational suppliers and exporters is also consistent with our model’s predictions.

Home country characteristics as drivers of firms’ type choices While the evidence suggests that on average firms seem to prefer exporting to supplying multinationals, it is interesting to examine if this pattern is sensitive to the characteristics of each country, as predicted in Proposition 2. It can be noted from the estimation of model M1 that the marginal effects of country dummies are jointly significant in all three outcomes. Therefore, operating in different countries with different characteristics would affect firms’ choices. In analysing the marginal effects of home country characteristics, we use the estimation results from model M2 since those interesting characteristics are not included in model M1. In particular, the fixed costs to invest and to export are supposed to be the decisive factors affecting firms’ choices.

We first investigate whether a reduction in investment costs (proxied by FDI inflows over the rest-of-the-world GDP) has an effect on the probability of choosing between supplying multinationals and exporting. Our model suggests that lower investment costs reduce the productivity threshold for firms entering the multinational market while raising the productivity threshold for firms desiring to export. Therefore, an increase in FDI inflows over the rest-of-the-world GDP (our proxy for a decrease in investment costs) is expected to have a positive effect on the probability of becoming multinational suppliers and a negative effect on the probability of exporting.

The estimated marginal effects of FDI inflows on the probability of each outcome are reported in Table 8. The opposite signs on the probability to export and to supply multinationals provide strong evidence in favour of FDI inflows affecting the choice between the two strategies, as predicted by Proposition 2 of our model. Specifically, the estimates show a positive effect of FDI inflows on the probability of supplying multinationals with a magnitude of 2.2pp, and a negative effect on the probability of exporting with a magnitude of 6.7pp for a small increase in FDI inflows at the mean. This implies that firms tend to supply more to multinationals than to export as FDI inflows increase.Footnote 12

It should be noted that the reported marginal effects are estimated at the mean of both ex-ante labour productivity and FDI inflows. To see if there is a switch in firms’ preferred strategies when there is a change in FDI inflows, we examine firms’ probability of choosing each strategy when FDI inflows increase from the lowest level (that of Kyrgyzstan) to the highest level in the sample (that of Ireland). Figure 2 compares the estimated marginal effects of ex-ante labour productivity under these two scenarios of FDI inflows at different levels of ex-ante labour productivity, while keeping all other factors at their mean values.

The switch in the relative position of the probability to export (red line) and the probability to become a multinational supplier (blue line) in the two panels suggest that firms’ preferences over the two outcomes depend on investment costs, as in Proposition 2 of our model. In particular, when FDI inflows are at their lowest level (left panel), which is consistent with the low trade costs/high investment costs case, exporting is the dominant strategy for firms. When FDI inflows are at their highest level (right panel), which is consistent with the high trade costs/low investment costs case, supplying multinationals is the dominant strategy for firms compared to exporting.

Moreover, for countries with high levels of FDI inflows, the probability to do both activities (purple line) increases considerably, and is higher than the probability of doing either activity even for firms with relatively low levels of labour productivity. This implies that, in such a case, the productivity cutoff of doing both activities is particularly low. As a point of reference, for countries with an average level of FDI inflows as in Fig. 1, the probability of doing both activities is higher than that of either activity only for the top 5% productive firms. Instead, for countries with low FDI inflows, the probability of doing both activities is close to zero even for the most productive firms.

Next, we analyse the effect of fixed trade costs (proxied by the number of documents required to export) on the probability of choosing between exporting and supplying multinationals. The estimated marginal effects of export fixed costs in Table 8 suggest that, for a firm with average productivity, a small increase in export costs raises the probability of supplying multinationals by 2.5pp while lowering the probability of exporting by 10pp. The difference in marginal effects on the two outcomes is as large as 12.6pp and it is statistically significant. This is evidence in support of export costs affecting the choice between the two strategies as indicated in Proposition 2, which suggests that firms prefer to supply multinationals when exporting becomes more costly.Footnote 13

To examine the possibility of a switch in preferences from exporting to supplying multinationals depending on the size of export costs, the marginal effects of labour productivity on the probabilities of the four outcomes are estimated under two scenarios: when the number of documents required to export is as low as 2 as in Ireland (the lowest in the sample), and when the number of documents required to export is as high as 15 as in Kyrgyzstan (the highest in the sample), keeping all other factors at their mean levels.

Figure 3 shows that firms’ preferences over the two outcomes depend on export fixed costs, as reflected by the relative position of the probability to export (red line) and the probability to become a multinational supplier (blue line) in the two panels. In both cases, however, exporting is still the dominant strategy for suppliers compared to supplying multinationals as in the second scenario of Proposition 2. This is seemingly inconsistent with the model, where supplying multinationals is expected to be a dominant strategy when fixed export costs are high. However, we should recall that the second scenario of Proposition 2, i.e., supplying multinationals is preferred to exporting, only occurs at sufficiently high levels of both export fixed costs and transportation costs relative to fixed investment costs. In this sample of mainly Eastern European countries, transportation costs and fixed export costs may not be high enough to satisfy the condition in Eq. (32) of “Appendix 1” and reverse the relative probability of choosing between exporting and supplying multinationals given the close geographical distance to the main foreign market, i.e., Western Europe. Finally, the probability of doing both activities increases considerably and is higher than the probability of exporting only when export costs are high. This is again consistent with our model.

4.3 Sensitivity analysis

In this section we present some robustness checks for our results. First, we show that our results are robust to the use of alternative proxies for the fixed costs to set up a multinational subsidiary and to export in the home country.

As an alternative to the FDI inflows ratio, we use separately the average time required to start a business, the average number of start-up procedures to register a business and the corporate tax rate in the host country. In place of the number of documents necessary to export, we use the average time necessary to comply with all procedures required to export goods and the average time to clear exports through customs.

“Appendix 4” reports these additional estimation results. All results are statistically significant and consistent with our main results. The marginal effects of fixed investment costs (Table 10) and fixed export costs (Table 11) on the probability to export and the probability to supply multinationals are significant and show consistently opposite signs. These results confirms our findings that fixed investment costs and fixed export costs are significant determinants of firms’ choice between exporting and supplying multinationals.

We also attempted to use import tariffs of the host country as a proxy for investment costs. As a barrier to trade, import tariffs can encourage productive foreign final producers to set up multinational presence in the host country to avoid trade barriers and, thus, can potentially increase the opportunity to become multinational suppliers for domestic firms. Import tariffs, however, can be highly correlated with export costs, given that they both measure a country’s level of openness and can have a negative effect on all firms, including intermediate suppliers. Table 10 in “Appendix 4” shows that import tariffs have a negative effect on the probabilities of all choices. We do not see the opposite effects of investment costs and export costs on firms’ choice of strategy. The marginal effects of export sunk costs become less significant since they are correlated with import tariffs. This is expected because we cannot separate the effect of investment costs and the effect of trade costs on firms’ decisions as in our model when using import tariffs.

Second, to separate intermediate suppliers from possible final producers in the sample, we exclude firms that sell all their products to small firms (with less than 250 workers) and individuals. We then estimate our model using the remaining subsample of 3668 identified intermediate suppliers with positive sales to large firms, parent firms, state-owned enterprises or multinationals. The results, presented in Table 12 in “Appendix 5”, are statistically significant and consistent with our main results.

Third, we test that our results are robust to potential endogeneity concerns linked to learning effects. While the use of ex-ante labour productivity at time \(t-3\) in our empirical analysis can minimize the endogeneity issue of labour productivity, one may argue that firms’ status may not change over this period. Assuming there are learning effects from multinationals that improve their suppliers’ labour productivity, being a multinational supplier at both time t (year 2005) and time \(t-3\) (year 2002) could influence a firm’s ex-ante labour productivity and produce a bias in our MNP estimation.

To test if there is a direct learning effect from multinational customers to their suppliers, we regress changes in firms’ labour productivity between 2002 and 2005 on their current supplier status, their lagged supplier status and the interaction terms of the two statuses. We use a subsample of 1128 firms observed in both 2002 and 2005 with information on both their current supplier status and lagged supplier status, i.e., whether a firm is an exporter and/or a multinational supplier in 2005 and in 2002. The estimation results show that being a multinational supplier in 2005 or in 2002 or in both years is not associated with changes in firms’ labour productivity during this period (see Table 13 in “Appendix 6” for the estimation results). Being an exporter in 2005, whereas, results in an improvement of labour productivity between 2002 and 2005. On the other hand, being an exporter in both 2002 and 2005 is associated with a decrease in labour productivity between 2002 and 2005, but the significance level is low. The results suggest that there is little evidence for direct learning effects from multinationals to their suppliers during the period 2002–2005 in our subsample.

Moreover, in our above-mentioned subsample, 164 firms are multinational suppliers and 964 firms are not multinational suppliers at time \(t-3\) (2002), among which 91 firms become multinational suppliers and 873 firms remain as non multinational suppliers at time t (2005). For these 964 firms that are not multinational suppliers at time \(t-3\), their lagged labour productivity can be considered exogenous with respect to the decision of becoming multinational suppliers at time t. Table 14 in the “Appendix 6” provides the estimation results based on specification M1 using the subsample of firms that are not multinational suppliers at time \(t-3\). The results show that ex-ante labour productivity is still a significant predictor of firms’ choice of supplying strategy. Thus, our main results are robust to potential endogeneity issues due to learning effects.

It should be noticed that we do not exclude the possibility of indirect learning effects, i.e., the backward spillover effects from multinationals in general on non-multinational suppliers, as such learning effects do not lead to endogeneity issues and, thus, do not affect the reliability of our MNP analysis. Indeed, a firm that does not supply multinationals can deliberately make its own investment or learn from multinationals and multinational suppliers in order to become more productive and gain a supply contract with multinationals itself.

Fourth, our model implicitly predicts that there should be no differences between indirect exporters and domestic-oriented suppliers. To test for the differences between indirect exporters, which have been excluded from our main analysis, and direct exporters, we include indirect exporters as an additional outcome in our MNP model. The results are presented in “Appendix 7”. As expected, the insignificant marginal effect of ex-ante labour productivity suggests that indirect exporters are no different from domestic-oriented suppliers. The insignificant effect could, however, be due to the small number of observations for indirect exporters as there are only 213 indirect exporters in our sample, 116 of which are for year 2005.

Fifth, we consider the potential presence of processing traders in the data we use and the fact that they may behave differently compared to true exporters and true multinational suppliers. However, our data do not provide direct information on whether a firm engages in processing trade or not. Thus, to explore the role of potential processing traders, we examine those exporters or multinational suppliers whose inputs are totally imported from abroad and compare them with other foreign-oriented firms with less than 100% foreign inputs. “Appendix 8” reports the additional results. As shown in Table 16, exporters or multinational suppliers with 100% foreign inputs have similarly high levels of labour productivity, ex-ante labour productivity, wages and R&D expenditure as exporters or multinational suppliers with less than 100% foreign inputs. This suggests that those exporters or multinational suppliers with 100% foreign inputs do not seem to have different characteristics compared to other foreign-oriented firms in our sample. As a robustness check, we define potential processing traders as firms with a percentage of foreign inputs equal to 90% or more and our conclusions stay the same. Further, we adjust our multinomial probit model by including five groups for firms: suppliers to domestic final producers, suppliers to multinationals that have a positive share of domestic inputs, exporters that have a positive share of domestic inputs, both multinational suppliers and exporters that have a positive share of domestic inputs, and either multinational suppliers or exporters that only use foreign inputs. The results, provided in Table 17, show that ex-ante labour productivity remains the driving factor for firms’ choice among exporting, supplying multinationals, doing both and importing all their inputs.

Finally, though we do not discuss the behaviour of importers in our model, importing firms are often more productive than non-importing firms and the former firms tend to show characteristics similar to exporters. Thus, we run a robustness check to control for firms’ import activity by including import status in our multinomial probit estimation. The results are reported in Table 18 in “Appendix 8”. As expected, firms’ import status is a significant factor affecting firms’ strategies. Importing inputs significantly increases the probability of supplying multinationals, exporting or doing both. After controlling for import activity, ex-ante labour productivity is still a significant determinant of firms’ choices, as are our main variables of interest, including FDI over the rest of the world GDP and export sunk costs.

5 Conclusion

This paper investigates the important but so far neglected area of intermediate suppliers’ behaviour, namely the self-selection of intermediate suppliers into different supply strategies. We present and analyse a theoretical model and then test its predictions using firm-level data from a cross-section of 29 economies in Europe and Central Asia for years 2002 and 2005. We found that ex-ante labour productivity is the key predictor of intermediate suppliers’ choice of strategies. As firms’ productivity increases, domestic suppliers become more likely to export and/or supply multinationals and less likely to serve only local final producers. Suppliers can also choose to both export and supply multinationals but only the most productive suppliers are able to do so. With regard to the choice between exporting and supplying multinationals, firms’ preferences for one strategy over the other depend on ex-ante labour productivity and on home countries’ and sectors’ characteristics.

A significant contribution of this research is to provide a framework to analyse the effects of trade liberalization and investment liberalization together with firm behaviour. In particular, the model predicts that, in countries and sectors with low trade costs and high investment costs, the productivity cutoff for multinational suppliers is higher than that for exporters. In this case, exporting or doing both activities are the profit maximising strategies for highly productive firms as opposed to supplying multinationals only. On the other hand, in countries or sectors with high trade costs and low investment costs, the productivity cutoff for exporters is higher than that for multinational suppliers. Domestic suppliers in such sectors and countries prefer supplying multinationals or doing both activities over exporting alone.

The empirical evidence supports the predictions of our model. The results show that there is significant and consistent self-selection of more productive firms into supplying multinationals and exporting. Both exporters and suppliers to multinationals tend to be larger, have higher investment, R&D and marketing costs and pay higher wages to workers in comparison to domestic-oriented suppliers. Compared to exporting firms, multinational suppliers are found to be relatively younger, smaller, more productive and pay higher labour wages.

We also find evidence suggesting that firms’ choice in favour of exporting or supplying nationals depends on investment costs, proxied by FDI inflows, and trade costs, proxied by the number of documents required to export. It is shown that, when FDI inflows increase, the probability of supplying multinationals increases while the probability of exporting decreases. An increase in FDI inflows also increases the probability of firms doing both activities and the probability of serving domestic customers only. On the other hand, an increase in export set-up costs raises the probability of supplying multinationals and lowers the probability of exporting. This is consistent with the predictions of our model.

Moreover, in our sample, on average higher ex-ante labour productivity is required to become a multinational supplier while it is easier for firms to export. This result suggests that the case of low trade costs/high investment costs is prevalent in our sample of mostly transition economies. Thus, it is arguable that the institutional features of these countries at the time led them to promote trade liberalisation, possibly also due to the close proximity to large markets in Western Europe, rather than investment liberalisation and FDI inflows.

Finally, these robust findings in favour of self-selection of multinational suppliers also suggest that the claimed spillover effects from multinationals to local suppliers need to be re-examined both theoretically and empirically. For instance, they may help to explain the lower spillover effects from FDI found in some papers when firms’ fixed effects are included in the empirical analysis. As home countries’ characteristics are found to influence the self-selection effects to a considerable extent, our study may also help to explain the inconclusive findings about FDI spillover effects across different studies using data from countries with different characteristics. On the other hand, these results can be used as evidence in favour of the pro-competitive effect on the productivity of local suppliers due to the presence of multinationals. A large presence of multinationals, corresponding to large FDI inflows in our analysis, can result in greater competition and an increase in the productivity cutoff of producers in the final goods market. This, in turn, may heighten the productivity cutoff of domestic-oriented and exporting suppliers.

Notes

In order to focus on the behaviour of suppliers and to avoid further complications (i.e., to have just three types of suppliers as described in “Appendix 1” instead of potentially six types), we treat all final producers operating in their home country as a single group without disaggregating them further into domestic-oriented and exporting firms. We also consider a model of 6 types of suppliers corresponding to different types of final producers, i.e., domestic-oriented firms, exporting firms and multinationals in each of the two countries, and obtain similar results (see Pham 2015).

These assumptions come from the fact that exporting implies that a supplier needs to set up new distribution channels in the foreign country, whereas, when selling to multinationals in the domestic market, a supplier can use its existing distribution channel and save on that cost. Furthermore, on their part, multinationals often actively research the host country market before entering, so there is a high chance that the currently supplied intermediate varieties of local suppliers are compatible with the production requirement of multinationals. It is, however, possible that multinationals have more stringent requirements for intermediate inputs such that it is more costly for a supplier to tailor its product to win a contract with a multinational.

Countries included in the BEEPS dataset are Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Ireland, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Additional results are available upon request.

We have also run our main empirical model using the smaller subsample of 4497 observations and all results are consistent with those based on the larger sample used in the baseline specification. These additional results are available upon request.

We exclude firms that do not export directly but only export indirectly through other firms because direct exporters tend to pay more fixed entry costs, as described in our model, compared to indirect exporters.

Time t-3 is chosen because data are only available at that point in time as described in the data description.

“Appendix 2” shows the cumulative distribution functions of firms’ ex-ante labour productivity distributions in 2002 and 2005 across the four firm categories.

We choose the MNP model because the multinomial logit model with its strict assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) may be problematic in our case. For each supplier, the opportunity to export would change the odds ratio of supplying to multinationals and doing both activities and, similarly, having the opportunity to do both activities would affect the odds ratio of supplying to multinationals and exporting. The MNP model allows for different alternatives to be correlated and, hence, it is more reliable for this analysis.

In “Appendix 9”, we consider an adjustment of the main model by adding interactions between foreign ownership and other key variables, including country characteristics (GDP, FDI inflows, export sunk costs) and sector dummies. However, it should be noted that the results based on the adjusted model do not change qualitatively compared to the main model presented above.

Figure 5 in “Appendix 3” presents the marginal effects of FDI inflows at different levels of FDI inflows and different levels of firm ex-ante labour productivity. The results are significant and consistent with the marginal effects estimated at means.

In “Appendix 3”, we also examine these marginal effects at different levels of export costs and ex-ante labour productivity (see Fig. 6). The results are significant and consistent with the results estimated at means.

References

Amiti, M., & Konings, J. (2007). Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs, and productivity: Evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Review, 97(5), 1611–1638.

Antras, P., & Helpman, E. (2004). Global sourcing. Journal of Political Economy, 112(3), 552–580.

Bekes, G., & Murakozy, B. (2018). The ladder of internationalization modes: Evidence from European firms. Review of World Economics, 154(3), 455–491.

Bernard, A., & Jensen, J. (1999). Exceptional exporter performance: Cause, effect, or both? Journal of International Economics, 47(1), 1–25.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2009). How firm capabilities affect who benefits from foreign technology. Journal of Development Economics, 90(2), 192–199.

Blomstrom, M., & Kokko, A. (1998). Multinational corportations and spillovers. Journal of Economic Surveys, 12(3), 247–277.

Carluccio, J., & Fally, T. (2013). Foreign entry and spillovers with technological incompatibilities in the supply chain. Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 123–135.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1707–1721.

Delgado, M. A., Farinas, J. C., & Ruano, S. (2002). Firm productivity and export markets: A non-parametric approach. Journal of International Economics, 57(2), 397–422.

Eaton, J., Kortum, S., & Kramarz, F. (2011). An anatomy of international trade: Evidence from French firms. Econometrica, 79(5), 1453–1498.

Godart, O., & Gorg, H. (2013). Suppliers of multinationals and the forced linkage effect: Evidence from firm level data. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 94, 393–404.

Halpern, L., Koren, M., & Szeidl, A. (2015). Imported inputs and productivity. American Economic Review, 105(12), 3660–3703.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Yeaple, S. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Javorcik, B. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627.

Javorcik, B., & Spatareanu, M. (2009). Tough love: Do Czech suppliers learn from their relationships with multinationals? Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 111(4), 811–833.

Javorcik, B. S., & Spatareanu, M. (2005). Disentangling FDI spillover effects: What do firm perceptions tell us? In B. S. Javorcik & M. Spatareanu (Eds.), Does foreign direct investment promote development? (pp. 45–71). Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

Kasahara, H., & Rodrigue, J. (2008). Does the use of imported intermediates increase productivity? Plant-level evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 87(1), 106–118.

Keller, W., & Yeaple, S. (2009). Multinational enterprises, international trade, and productivity growth: Firm level evidence from the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(4), 821–831.

Lawless, M. (2009). Firm export dynamics and the geography of trade. Journal of International Economics, 77(2), 245–254.

Lin, P., & Saggi, K. (2007). Multinational firms, exclusivity, and backward linkages. Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 206–220.

Markusen, J., & Venables, A. (1999). Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. European Economic Review, 43(2), 335–356.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Melitz, M., & Ottaviano, G. (2008). Market size, trade, and productivity. Review of Economic Studies, 75(1), 295–316.

Meyer, K., & Sinani, E. (2009). When and where does foreign direct investment generate positive spillovers a meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1075–1094.

Nicolini, M., & Resmini, L. (2010). FDI spillovers in new EU member states. Economics of Transition, 18(3), 487–511.

Pham, V. T. (2015). Heterogeneous intermediate suppliers and product quality under trade and investment liberalization. Ph. D. thesis at School of Economics, UNSW Business School, University of New South Wales.

Serti, F., Tomasi, C., & Zanfei, A. (2010). Who trades with whom? Exploring the links between firms’ international activities, skills, and wages. Review of International Economics, 18(5), 951–971.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148(2), 235–267.

Acknowledgements

Woodland gratefully acknowledges that this research was supported by a Grant from the Australian Research Council (DP140101187).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trento within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Model and proofs of propositions

1.1 Appendix 1.1: Final consumer

The utility function of a representative consumer over a continuum of final good varieties in a country has a standard Dixit-Stiglitz constant elasticity of substitution (CES) form

where \(q_{j}\) is the consumption of a variety j, which is produced by final producer j, and \(\theta >1\) is the elasticity of substitution between any two different final good varieties.

The utility maximisation yields the following demand for each final good variety in terms of price and income

where Y is national income, \(p_{j}\) is the price of a variety of the final good and P is the price index of final good varieties

As the two countries are assumed to be symmetric, consumers in each country have the same income Y and face the same final good price index P.

1.2 Appendix 1.2: Final producers

1.2.1 Appendix 1.2.1: Production technology and cost function