Abstract

To increase labour market participation among migrants, an increase in female labour market participation is important, with wages being a significant incentive. In research on the gender wage gap, the consideration of housework has been a milestone. Gender differences in housework time have always been much greater among migrants than among native-born individuals. Based on data obtained from the German Socio-Economic Panel from 1995 to 2017, this study questioned whether housework affects the wages of migrant full-time workers differently than those of their native-born counterparts. To consider the possible endogeneity of housework in the wage equation, the analysis estimated, in addition to an OLS model, a hybrid model to estimate within effects. Significant negative effects of housework on wages resulted for migrant women and native-born individuals. The effects for migrant men were significantly smaller or insignificant, which could not be explained by threshold effects. The greater amount of time spent on housework by migrant women than by native-born women will in general lead to a larger wage decrease due to housework for migrant women than for native-born women. The results further showed that the observed variables explained very little of the migrants’ gender wage gap, in contrast to the gap of native-born individuals. Human capital returns, including education and work experiences, were much lower for migrant women than for native-born women, whereas differences in housework equally contributed to the explained share of the gap for both groups, indicating the greater relevance of housework for migrants’ wage gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immigrants are an integral part of most industrial countries’ societies, while they have usually much greater problems of labour market integration than natives. This debate has often focused on men, but greater attention to women is highly relevant. Apart from gender differences in employment rates, large gender wage gaps have contributed to problems for female migrants’ labour market integration and decreased their incentives to participate. Data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) from 2017 showed that, among full-time workers living in couple households, the gross hourly wage gap was 14% among migrants (and 19% among native-born individuals), and the unconditional gross hourly wage gap was 23% among migrants (and 16% among native-born individuals).

Economists have traditionally explained structural gender inequality in earnings based on differences in human capital variables, occupations, industries and firms or based on discrimination. Modern approaches have also considered psychological attributes or noncognitive skills (Blau and Kahn 2016). As a different cause of the gender wage gap, Becker (1985) emphasised gender differences in time spent on housework. Empirical studies that found wage decreases due to housework time examined differences by gender and housework task, among other factors. Descriptive analyses showed that gender differences in housework time were much greater among migrants than among native-born individuals. Using data from the GSOEP from 1995 to 2017, this study analysed whether the effects of housework on wages differed between migrants and native-born female and male full-time workers living in households together with a partner. In addition to ordinary least squares (OLS), the analysis used a hybrid model to estimate within effects in a random effects (RE) model, analysing the effects of housework on wages and considering the endogeneity of housework in the earning equation. Furthermore, based on the Oaxaca-Blinder wage decomposition, the study examined the extent to which gender differences in housework contributed to the explained share of migrants’ gender wage gap, compared to that of the native-born gender wage gap.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The following section provides some background. Then, the paper introduces the dataset and presents descriptive statistics. The paper further describes the econometric specifications and presents the results. Finally, the last section concludes the study.

Background

Although time spent on housework has low returns compared to time spent on education or paid work, the amount is much greater than usually assumed (Hersch and Stratton 1997). According to Schwarz (2017), the value of time spent on household production in 2013 for Germany was approximately 40% of the gross national product. Becker (1985) emphasised the impact of housework on the gender wage gap due to large gender differences in time spent on housework. Developing a formal model, he argued that tasks such as childcare, food preparation and other forms of housework are tiring; therefore, women engaged in these tasks exert less effort on each hour of work in the labour market. Furthermore, he emphasised that these tasks limit access to jobs that require travel or odd hours. The following presents the relevant literature, discusses why the issue is highly relevant for migrants and formulates hypotheses for empirical analysis.

Using data from different countries, previous studies have found negative effects of housework on earnings, especially for women (see Anger and Kottwitz 2009; Bonke et al. 2003; Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz 2010; Hersch and Stratton 1997, 2002; Noonan 2001; Phipps et al. 2001). Empirical studies have investigated differences by housework tasks, working hours and living situations, among other factors. Ribar (2012) emphasised that economic research on immigrants’ time use has focused on market work behaviour due to its availability and relevance to economic integration. Nevertheless, some studies have discussed how differences in time spent on various non-market work activities between immigrant and native-born individuals can influence immigrants’ well-being or integration and whether the results relate to cultural factors or opportunity costs of time (Anastario and Schmalzbauer 2008, Hamermesh and Trejo 2010; Vargas and Chavez 2010; Zaiceva and Zimmermann 2011). Zaiceva and Zimmermann (2014) focused on time spent on non-market activities and the effect on the labour market performance of non-white women living in the UK. Given the low labour market participation of ethnic minority women and their generally lower opportunity costs of time, the authors provided evidence that non-white women spend significantly more time on religious activities and food management than white women. Ribar (2012) showed that immigrant time use is more gendered in the sense that immigrant men tend to devote less time to housework than native-born men, whereas immigrant women tend to work more hours in the household than native-born women. The present study contributes to the literature in the following ways. Studies have analysed the time use of migrants, but to the author’s knowledge, no study has directly estimated the impact of housework on wages separately for migrants and compared the contribution of housework to the gender wage gap between migrants and native-born individuals. Many studies have used data for the US or UK to examine the effects of housework on wages. Anger and Kottwitz (2009) and Hirsch and Konietzko (2011) used German data (from the GSOEP as well) but did not separately investigate migrants. Several migration samples have been added to the GSOEP in recent years, and the GSOEP therefore now has a large amount of data on migrants, while data on migrants still represent a small overall share of the dataset. Furthermore, other studies have estimated fixed effects (FE) models to consider the endogeneity of housework in the wage equation. To consider time-invariant variables, such as education, together with unobserved factors, this study used a hybrid model to estimate within effects in the RE model.

As shown in Table 1, the gender gap in time spent on housework tasks was much larger among migrants than among native-born individuals. Zaiceva and Zimmermann (2014) discussed whether time spent on food management and religious activities was very long for non-white women due to socio-cultural norms, preferences, gender role attitudes, or the opportunity costs of time. Concerning opportunity costs, the family migration model can provide explanations for the large gender gap in housework time among migrants.

The Family Migration Model

Researchers have used microeconomic migration models to analyse the decision to migrate in the context of individual utility maximisation (Sjaastad 1962). Massey et al. (1993) indicated that, by comparing costs and benefits, individuals move when the net return from moving is positive. Similarly, a family’s migration decision is based on the family utility from moving. Nevertheless, as Shauman and Noonan (2007) emphasised, within the family, individual costs and benefits are likely to be unequally distributed. Following Mincer (1978), the person with lower positive or negative returns becomes the so-called “tied” mover or stayer. Although this perspective is not explicitly gendered, according to human capital theory, women have a greater likelihood than men of being a tied partner. Married women have, on average, more discontinuous employment histories; they are therefore less able to develop careers and tend to concentrate in lower paid jobs (Halfacree 1995). Many studies have provided evidence of the negative effects of migration on married women’s earnings (see, e.g., Cooke et al. 2009; LeClere and McLaughlin 1997). Shauman and Noonan (2007) showed that, apart from structural gender inequality, the lower earnings of migrant women are due to their greater likelihood of having a secondary role in family migration decisions and therefore a greater likelihood of being a tied mover. Unequal labour market integration and unequal earnings within a couple likely have large impacts on the division of housework tasks within migrant couples. As Carlson and Lynch (2017) argued, couples determine who is responsible for housework by bargaining with one another – a process in which the spouse with more resources is able to negotiate out of housework. For couples with relatively unequal educational levels and unequal earnings, it can also be efficient for the spouse with the higher income –relative to that of the other spouse– to concentrate on paid market work. The large gender gap in time spent on housework could result from the lower earnings of migrant women compared to those of their partners. This study examines whether the large gender gap in time spent on housework further worsens the earning potential of migrant women, considering the possible endogeneity of housework in the wage equation.

Hersch and Stratton (1997) emphasised that small amounts of housework time (for many men) require little effort and fit into almost any schedule, whereas large amounts of time spent on housework responsibilities are tiring and can reduce the effort exerted on market activities. Threshold effects are one explanation for the insignificant or small effects of housework on wages found in some studies for men (Hersch 2009; Hersch and Stratton 1997). Threshold effects refer to a circumstance in which the significant effects of one variable occur only when the respective variable approaches a certain amount.

Following the findings of other studies, this study hypothesised (H1) that, due to threshold effects, housework has a negative effect on migrant women’s wages but an insignificant or smaller effect on migrant men’s wages. H1 is in line with the household responsibility hypothesis (HRH) discussed by Giménez and Molina (2016). The authors aimed to explain the observed gender differences in commuting behaviour in relation to household responsibilities, which are usually greater for women. They showed that the effect of home production on commuting time for women was more than double the effect for men and that childcare time affected only women’s commuting behaviours. The HRH suggests that the disproportionate burden of household responsibilities on women requires shorter commute times and renders it difficult for them to work any distance away from home. As Giménez and Molina (2016) emphasised, their results could help to predict future location decisions of employers who want to employ women who might or might not be spatially restricted. Furthermore, the results are relevant for employment policies since more family-friendly policies increase the desire of women to work farther from home and therefore increase their labour force participation.

Due to the much greater gender differences in time spent on housework, the study further hypothesised (H2) that housework is more relevant for the gender wage gap of migrants than for that of native-born individuals.

Data and Descriptive Statistics

The empirical analysis used data from the GSOEP from 1995 to 2017. For more information on the GSOEP, see http://www.diw.de/soep. The GSOEP is an ongoing representative panel survey of private households in Germany that started in 1984 in West Germany and was enlarged to include East Germany after 1990. The survey collects information about time spent on primary daily activities, employment behaviours and socio-demographic variables over time.

The analysis considered full-time working migrant and native-born men and women between the ages of 20 and 60 years old who lived together with a partner. Full-time workers have greater time restrictions than part-time workers (full-time occupations in Germany range from 36 to 40 working hours per week); therefore, the two groups should not be aggregated, and the analysis considered only the former group. Furthermore, individuals living in couple households should not be aggregated with individuals living alone because they are not part of an intrahousehold arrangement/bargaining process regarding the distribution of time spent on housework. The sample selection did not consider the working time of the partner; the sample included full-time workers who lived with a partner who was or was not full-time (generally) employed. Fifty-one (seventy-six) percent of the individuals had a full-time employed (generally employed) partner. The sample excluded interns and individuals in vocational training, as well as second-generation migrants (individuals born in Germany with one or both parents born outside Germany). Furthermore, the sample excluded couples consisting of a migrant and a native-born individual. The sample contained 130,388 observations of 25,716 full-time workers living in 19,041 couple households. The share of migrants equalled 19%.

The consideration of only coupled individuals in the sample did not lead to uneven selection by a migration background or gender. In the GSOEP from 1995 to 2017, among persons between 20 and 60 years of age (excluding the aforementioned groups), the share of individuals living in couple households equalled 84–85% among migrant women and men and 77% among native-born women and men. In contrast, the consideration of only full-time workers led to the analysis of a select group of women, especially migrant women. This selection should be considered when interpreting the results. Among the migrants, only 26% of women and 57% of men were full-time employed (51% of women and 65% of men were generally employed). Among the native-born individuals, 48% of women and 84% of men were full-time employed (82% of women and 89% of men were generally employed). In the final sample, the share of women was 29% among migrants and 36% among native-born full-time workers.

The GSOEP questionnaire asks about hours per working day spent not only on housework (including washing, cooking and cleaning) but also on childcare and errands, as well as repairs on and around the house, car repairs and garden work. Because repair tasks and garden work are highly time flexible and can easily be performed during the weekend or in the evening, they should not significantly influence earnings. Previous studies have shown that the greatest negative effects on earnings exist for tasks that constitute part of a daily routine (Bonke et al. 2003; Hersch and Stratton 2002). For migrants, the category of errands, including trips to government agencies, depends greatly on the time since migration and other migration-relevant issues, such as migration status. Although childcare is even more time inflexible than washing, cooking or cleaning, the sum of housework hours and childcare hours is not a reliable indicator. It is possible that respondents performed both types of tasks at the same time and that they reported spending time on one or both categories on the questionnaire. Furthermore, Kimmel and Connelly (2007) suggested that childcare time should not be aggregated with home production because it behaves differently in response to demographic differences, diary day, or predicted prices of time. Their results showed that higher maternal wages decrease home production, while caregiving time (comparable to employment time) increases home production. They emphasised the investment component of childcare and employment, in contrast to home production. This study considered only time spent on the tasks of washing, cooking and cleaning.

Table 1 reports the average hourly wage and hours worked of full-time workers living in couple households per working day, as well as the respective gender gap, not using sample weights by migration status and gender. The percentage gender gap in time spent on housework was much greater for migrants than for native-born individuals at the time of the survey. Because full-time working migrant women were a more selected group than full-time working native-born women, their gender wage gap was smaller than that of native-born individuals.

Table 2 compares the mean or share of the remaining control variables considered in the estimations for foreign- and native-born women and men. In addition, the table reports the standard deviation between individuals. Migrants lived on average with a larger number of children in the household and had fewer educational years at the time of the survey than native-born individuals. For both foreign-born and native-born full-time workers, men had more work experience on average than women and had worked for a longer time at their current firms. The share of individuals with a university degree was almost 10% points higher among migrant women than among migrant men, whereas the share was three percentage points higher among native-born women than among native-born men. Among the observed migrants, 52% came from another European country, 25% came from a country of the former USSR, and 20% came from an Asian or Middle Eastern country.

Specification

The econometric analysis was based on the wage equation displayed in (1) below.

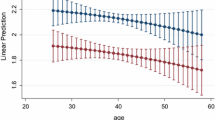

Here, lnwit is the log of the real gross hourly wage of individual i measured at time t, and Hit represents hours per working day spent on housework. X′it represents a vector of control variables, including the main determinants of wages. As listed in Table 2, X′it includes the age of the person, the number of children, the years of education, a categorical variable for the highest educational degree obtained, and years of work experience and years at the current firm (both in quadratic terms to control for nonlinear effects and scaled by 100 to display small effects). X′it also includes an indicator variable for whether a person has a disability, as well as an indicator variable, which equals 1 when the respondent evaluated his or her own health to be (very) good or satisfactory rather than bad or less good, and a categorical variable for the size of the current firm (grouped by the number of employees). Among other factors, due to the transferability of human capital, the estimation for immigrants also controlled for the country of birth, grouping individuals in the seven regions listed in Table 2. The sample included full-time workers who lived together with a partner who was either employed full/part time (76%) or not employed. It is questionable whether the estimation model should have considered the partner’s labour and non-labour working time since these variables also influence an individual’s wages indirectly due to the effect on the individual time spent on housework. The variables would have created endogeneity problems and were therefore not included in the estimation equation. The partner’s wage or educational degree also influences the individual’s wage. Blossfeld and Timm (2003) provided evidence of a high correlation of education and social attributes within couples in most countries. To control for assortative mating, X′it also includes the partner’s years in education. μit represents region fixed effects. To control for regional effects, the estimations included indicator variables for the sixteen federal German states. To control for time fixed effects (represented by νt in the equation), the estimations included year fixed effects. Finally, ρi represents personal fixed effects, and εit is the disturbance term.

The housework variable can be endogenous in the wage equation. Unobserved characteristics can be correlated with both housework and earnings and can be interpreted as the individual’s innate abilities or market productivity. Hersch and Stratton (1997) emphasised that workers with higher productivity specialise more in market production (also relative to their partners) and spend less time on housework. Simultaneity between housework and wages can also describe the endogeneity of the housework variable: Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz (2010) reported that individuals with higher earnings engage less in housework activities due to higher opportunity costs. These workers are more likely to substitute market purchases for home production and have superior household bargaining positions.

To consider the endogeneity of housework, previous studies have estimated wage equations applying FE and instrumental variable (IV) estimations, in addition to OLS. Studies have instrumented housework with various variables, such as spousal characteristics and earnings; the number and ages of children in the household; non-labour income; the size, type and ownership status of the residence; and gender ideology (see Bonke et al. 2003; Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz 2010; Carlson and Lynch 2017; Hersch and Stratton 1997; Hirsch and Konietzko 2011). As in many other contexts, instrument exogeneity must be questioned for possible exogenous variables. On the one hand, a high income or educational degree of one spouse relative to that of the other lowers the bargaining power of the latter with respect to the work share of housework tasks. On the other hand, the high earnings of one spouse can lower the incentive to invest in human capital and can therefore affect the future earnings of the other. Furthermore, many authors have emphasised the high correlation between education and social attributes within couples (Blossfeld and Timm 2003). Young or numerous children often reduce working time and increase hours of housework. Nevertheless, the existence of children might prevent the earnings of women from rising or at least being correlated with wages. Non-labour income and residence ownership or size increase the probability of paying someone to perform housework tasks but also increase the probability of receiving high wages. Concerning gender ideology, investments in education and therefore in earnings and labour market performance in general are often lower for women with more traditional values than for women with egalitarian gender values (Fortin 2005; Vella 1994), who usually also spend more time on housework tasks (Coltrane 2000). As an alternative IV estimator, past housework hours can function as an instrument for current housework hours. However, studies have emphasised that “lag identification” is almost never a solution to endogeneity problems and most often leads to incorrect inferences (Bellemare et al. 2017; Reed 2015).

FE models have the advantage of being able to control for unobserved time-invariant variables using the panel structure without the need for any exogenous variation. A problem concerning the estimation of the housework variable is usually low variation in self-reported hours spent on housework tasks over time. For the identification of effects, for each individual, the FE estimation uses only variations in variables from the individual means over time. Therefore, with a low variation over time, it is possible to find no significant effects of housework on wages. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation between individuals, as well as the standard deviation within individuals, for individual wage and housework hours for migrant and native-born women and men. The within standard deviation for the four groups ranged between 0.5 and 0.7 and was thereby larger than the within standard deviation of wages (which ranged between 2.4 and 4.3) relative to the mean. Nevertheless, wages are highly time persistent and therefore not a valid comparison group. Another drawback of FE models is their inability to estimate the effect of any variable that does not vary over time. The educational variables had very low within standard deviations among the considered full-time workers (especially for native-born individuals). Their dropouts constituted a relevant problem of the specification, determining the constant of the model. On the one hand, to circumvent the disadvantages of the conventional FE approach, this study estimated, in addition to the OLS model, within effects in the RE model. The so-called hybrid model decomposes time-variant variables into between (\(\overline{x_i}={n}_i^{-1}{\sum}_{t=1}^{n_i}{x}_{it}\)) and within (\({x}_{it}-\overline{x_i}\)) components (Schnuck 2013). On the other hand, because of the usually low variation in self-reported hours spent on housework tasks, within effects yielded only additional insights to confirm or reject the results of the OLS model.

The following describes the structure of the hybrid model in the context of the wage equation displayed in (1). Including Hit in X′it and excluding time-invariant variables from X′it in Z′it result in a general random intercept model:

where X′it includes the time-variant variables, and Z′it includes the variables that are time invariant in most cases for full-time workers (the individual’s and partner’s educational variables, the indicator variable for disability status and the indicator variable for the country of birth group). ρi represents personal-fixed effects and the random intercept, which varies by individuals; εit is the disturbance term. The hybrid model is provided by

where β1 presents the within (fixed)-effect estimate of the time-variant variables. Eq. (3) provides in the RE model that we used to estimate the effects of time-invariant variables, represented by β2. Finally, β3 estimated the between effect of time-variant variables. A comparison of β1 and β3, of the within and between effects of the housework variable, yielded information about the degree to which unobserved heterogeneity was responsible for the observed relationship between the wage and housework variables. The analysis used the Wald test to test the equivalence of the within and between estimates of the housework variable (Schnuck 2013). Similar to the Hausman test, the test checked the validity of the RE assumption, namely the conditional independence between group-specific fixed effects/intercepts and, in this case only, the housework variable. When the null hypothesis of equivalence is rejected, the between effect is biased because it is confounded with the fixed effects term. If housework directly influences wages in this case, housework will remain significantly negatively related to wages in the within coefficient (in case the housework variable sufficiently varies over time). When the null hypothesis of equivalence cannot be rejected, the housework coefficient resulting from the RE model is more efficient than that resulting from the FE or hybrid model.

We estimated the OLS and hybrid models separately for migrant and native-born women and men. For each group, the sample size was sufficiently large to draw inferences. The GSOEP is an unbalanced panel. New samples have been drawn almost yearly to adequately represent developments such as migration flows and to reduce the negative effects of survey-related panel attrition. The sample included 43% of migrant women, 33% of migrant men, 32% of native-born women and 24% of native-born men who were observed only once during the observation period. The within coefficients did not consider these observations. Although migrant women had a 10-11 percentage points greater likelihood of being observed only once than native-born women or migrant men, the GSOEP included several additional migrant-specific samples in recent years, and across 22 waves the number of observations was sufficiently high for migrant women. Living in a household with a partner or working full-time is a circumstance that changes over time. Nevertheless, the dropouts of individuals who were observed for more than 1 year but only 1 year during which they were living in a couple or working full-time did not lead to an estimation sample size that was too small for inference. A total of 3% of migrant women and native-born individuals, as well as 2% of migrant men, were observed only once when living in a couple household (but overall, over more than 1 year). Furthermore, 8% of migrants, 9% of native-born women and 5% of native-born men dropped out because they worked only 1 year in a full-time position.

Hypothesis H1 assumed that the effect of housework on migrant wages differs significantly by gender. After conducting separate estimations for women and men, the analysis performed the t-test to test whether gender differences in the effect of housework time on earnings were significant. A significant gender difference existed for all of the specifications of Table 3 with p < .001. To reduce the sole reliance on null hypothesis significance testing and complement inferential findings, literature in the social sciences has suggested to provide some effect size estimates when reporting p values (Brand et al. 2011). As Funder and Ozer (2019) emphasised, significant findings can result from a large sample size while corresponding to a small effect. The analysis additionally reported Cohen’s d to expresses the magnitude of the difference between the female and male housework coefficients in standardised deviation units that are metric free. Cohen (1977) set values of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 as the thresholds for small, medium and large effects, respectively. The later literature suggested that Cohen’s guidelines were too stringent, recommending values of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 as relatively small, typical, and relatively large effects, respectively (Funder and Ozer 2019).

Results

The Impact of Housework on Migrants’ Wages

This section presents the estimation results on the effect of housework on wages. The first part examines the whole sample of full-time working men and women who lived with a partner, whereas the second part discusses whether threshold effects were relevant, restricting the sample to positive housework hours.

Table 3 presents the estimation results of the OLS and hybrid models for the full sample, differentiating by gender and migration status, as well as additional results of the RE model for migrants. For migrants, the OLS results showed that the housework variable had a significant negative effect on gross wages that was significantly higher (p < .001) for women than for men. The effect size of the difference between women and men was with d > 0.9 large, following Cohen’s (1977) classification. When housework increased by 1 hour per working day, the wages of migrant women decreased by 2% on average, whereas the wages of migrant men decreased by 1%. Note that an increase of 1 hour is very large; the daily average was 2 hours for migrant women.

A comparison in the hybrid model of the between and within effects of housework provided additional insight into the results. The model estimated a significant effect of housework on wages of −3% between migrant women. A significant effect between migrant men was slightly but significantly lower; the gender difference had a large effect size. The within effect was insignificant for both women and men. If the error term was significantly correlated with the housework variable due to unobserved variables, the significant between-effect in contrast to the insignificant within effect would indicate that the effect of housework on wages existed for migrants only indirectly due to unobserved heterogeneity. Concerning the p value of the test, the null hypotheses of equivalence could be rejected at the 10% significance level (p = .084 for women and p = .066 for men). Nevertheless, the Chi2 of the Wald test was only 2.98 for women and 3.38 for men and thus was too small to reject the hypotheses (as a rule of thumb, the value should at least equal 5). Although the test does not provide a definitive answer, considering the result, the coefficients of the housework variable in the wage equation resulting from the FE model were less efficient than those resulting from the RE model for migrants. The test indicated conditional independence between individual-specific effects and the housework variable. In the RE model, the effect of housework on wages was insignificant for men and significant for women at the 10% level, indicating that female wages decreased by 1% with an additional hour spent on housework.

For native-born individuals, the effect of housework was significantly negative in both the OLS model and the hybrid model for the within and between effects (the within effect of native-born women was significant only at the 10% level). In all cases, men had slightly but significantly higher effects than women, and the gender differences had a large effect size. The OLS results indicated that wages decreased on average by 4% for every additional hour spent on housework for men and women. The effect of housework between native-born individuals was even greater than that in the OLS model, at −6% for women and − 8% for men. The within effect was for both less than −1%, and the null hypothesis regarding the equivalence of the two effects was rejected (for women: Chi2 = 58.71, p = .000; for men: Chi2 = 110.19, p = .000). Hence, for native-born individuals, the between effect of housework was possibly biased because it was confounded with the FE term. A significant correlation might have existed for native-born individuals but not for migrants due to migrants’ integration process, social norms or gender role attitudes. The significant within effect for native-born individuals (for women only at the 10% level) indicated that housework directly influenced wages, but comparable to the effect observed for migrant women, the effect was only −1%.

Most of the control variables displayed in Table 3 had the expected effect on wages. The effects of years of individual/partner education, a university degree, overall work experience and work experience at the same firm were very robust for all of the groups. Here, the advantages of the hybrid model over the FE model became apparent: the time-invariant coefficients showed a meaningful effect, and it remained possible to estimate the within effects of time-variant variables.

In summary, the effects of the hybrid or general RE model were smaller than those of the OLS model and were only significant at the 10% level for women; nevertheless, in general, they confirmed the significant negative effects of housework on wages for migrant women and native-born individuals. For migrants, the effects were significantly greater for women than for men or only significant (at the 10% level) for women. For native-born individuals, the effects were slightly but significantly higher for men than for women.

Threshold Effects for Migrants Working Full Time

For the US, Hersch and Stratton (1997) and Hersch (2009) found smaller or insignificant effects of housework on the wages of men. Hersch (2009) explained gender differences in effects with threshold effects, indicating that significant or large effects of wages on housework exist only if the time spent on housework approaches a certain value. The author showed that, when housework time equalled 60 min or more per day, it had a significant negative effect for men, as well as women. Because time spent on housework was distributed unevenly, especially among migrant couples, threshold effects could possibly explain the significantly smaller effect for migrant men than for women found in the OLS model.

Table 4 summarises the coefficients of the OLS specification for wage regressions of full-time working migrants by gender when restricting the sample to individuals with housework time equalling 1 or more or 2 or more hours and excluding persons with zero hours (the GSOEP examines only full hours). For individuals with at least 1 hour spent on housework, the effect of housework on wages remained significant for all groups except for migrant men. The number of observations was almost equal for women, whereas for men, approximately 43–56% of observations dropped out due to men spending zero hours on housework activities. In the sample of individuals spending at least 2 hours per day on housework, the effects were significant only for native-born women, with a smaller coefficient than that of the whole sample. Hence, threshold effects could not explain the significantly smaller effect of housework on the wages of migrant men than on those of migrant women in the OLS model. As expected, the number of observations for the sample spending at least 2 hours per day on housework was much smaller than that for the whole sample. That persons with high time constraints spent so much time on housework was likely the main reason that the effects were not significant or smaller. These persons might have enjoyed the time spent on housework, having a strong preference for a clean home or enjoying cooking.

Housework and the Gender Wage Gap Among Migrants

The extant literature has shown that differences in the amount of housework performed by men and women appears to play an important role in understanding men’s higher average wages (Keith and Malone 2005). The above-presented estimation results indicated that housework had a negative effect on both native-born and migrant women’s wages. This section describes the results regarding the contribution of differences in housework to the explained share of the gender wage gap of migrant full-time workers living in coupled households compared to that of their native-born counterparts, again based on the GSOEP from 1995 to 2017.

We used the Oaxaca-Blinder wage decomposition (Oaxaca 1973) to calculate the explained portion of the (log) wage differential and to measure the extent to which gender differences in housework time explained this gap. The results were based on a three-fold decomposition, which divided the wage differential into: (1) the part of the differential due to group differences in the predictors (endowment effect); (2) the contribution of the differences in the coefficients; and (3) an interaction term that accounted for the simultaneous existence of differences in endowments and coefficients between the two groups (Jann 2008). The results compared the decomposition between migrants and native-born individuals, as well as between women as the reference group and men as the reference group.

For migrants, the results indicated conditional independence between individual-specific effects and the housework variable (Table 3). In this case, OLS estimation methods produced consistent estimators. In contrast, for native-born individuals, the results indicated a significant correlation of the housework variable with the fixed effects term, and OLS estimates of the housework variable were possibly biased in the decomposition. On the one hand, for native-born individuals, the results of a decomposition based on the FE estimation could be less biased. On the other hand, as Heitmüller (2005) showed with Monte Carlo simulation, in the FE model including time-invariant regressors, omitted variables lead to substantially biased decomposition components. Hence, for native-born individuals, there was a trade-off between possibly biased OLS coefficients due to a significant correlation of an individual FE term with the housework variable and a possible bias of the decomposition components in the FE model due to the dropouts of time-invariant regressors. Heitmüller (2005) emphasised that dropouts of time-invariant variables in FE estimations are especially relevant when applying decomposition techniques to study differences in predicted conditional sample means. A constant term – resulting from time-invariant variables – might well differ across groups and might contain important information about the relative positions of each group. Therefore, the decomposition in this study was based on the OLS estimation for both migrant and native-born individuals.

Table 5 provides the results comparing migrant full-time coupled employees with their native-born counterparts using women or men as the reference group. With the female wage structure as the reference group, differences in the observed characteristics explained −82% of the migrants’ gender wage gap. Full-time working migrant women were a highly selected group in the sample; only 26% of all migrant women in the GSOEP from 1995 to 2017 worked full time, and the log wage gap was smaller than among native-born individuals. Therefore, migrant women’s average wage would further decrease by 82% of the log wage differential (−0.15) if they – as the reference group – had the men’s observed characteristics. There were significant negative shares for differences in the educational variables because women were slightly better educated than their male counterparts (Table 2), and education had a positive effect on wages. Differences in the country of origin, region and year indicator variables (summarised in the “others” category) contributed negatively to the migrant gender wage gap as well. Differences in time spent on housework significantly explained 17 percentage points of the explained share of the gap. The migrant women’s wages would increase by an average of 17% of the log wage gap (0.03) if they spent a comparably small amount of time on housework as migrant men. This share slightly decreased to - 11 percentage points of the explained share of the gap with the male wage structure as the reference group. The value was negative because it equalled the average % share of the log wage differential by which the men’s wages would change if migrant men spent, on average, as much time on housework as migrant women. The log wage gap was also negative, subtracting men’s from women’s average wage. Then, the overall explained share of the gender wage gap equalled −13%. Men’s average wages would, as in the common case, decrease if the men had the women’s characteristics, especially in terms of differences in housework, work experience and years at the current firm.

For native-born individuals, the explained share of the gender log wage gap did not differ based on the chosen reference group as much as it did for migrants (55% for women as the reference group and −56% for men as the reference group), and differences in the considered variables explained more of the gap for native-born individuals than for migrants. Full-time working women were not such a selected group among native-born women; women’s average wages would increase if women had the men’s characteristics, and the men’s average wages would decrease if men had the women’s characteristics. Gender differences in housework contributed 15–16 percentage points to the explained part of the native-born individual log wage gap.

Differences in housework contributed similar shares to the explained part of the respective gender log wage gaps for migrants and native-born individuals. The results were consistent with those reported by Hersch and Stratton (1997, 2002), who showed that the explained share of the gender (log) wage differential for the US in the 1980s and 1990s increased by 8–14 percentage points when differences in housework time were considered in the estimation. Nevertheless, in this study, the overall contribution of observable characteristics to the explained share was much smaller for migrants than for native-born individuals, leading to greater relevance of housework for the migrants’ gender gap.

Conclusion

This study examined whether housework affects wages differently for migrants and native-born individuals. Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz (2010) showed differences in the effects of housework on wages by working time and family constellation. This study focused on full-time workers living in couple households. Previous studies have documented that the amount of time spent on housework had a negative effect on wages, which was greater for women than for men (Anger and Kottwitz 2009; Bonke et al. 2003; Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz 2010; Hersch 2009; Noonan 2001; Phipps et al. 2001). Using German data, the results of this study showed that the effects for migrant women were significantly greater than those for migrant men or only significant for women. The coefficients of panel estimation models were smaller and less significant, but in general, they confirmed the OLS results showing significant negative effects for migrant women and native-born individuals.

As in previous studies, the analysis applied panel estimation models to control for the endogeneity of housework in the wage equation (Bonke et al. 2003; Bryan and Sevilla-Sanz 2010; Carlson and Lynch 2017; Hersch and Stratton 1997; Hirsch and Konietzko 2011). This analysis has limitations. As discussed in the specification section, there did not appear to exist a valid exogenous instrument. Furthermore, when self-reported time spent on housework does not vary sufficiently over time, it is possible to find no significant effects of housework with the FE approach or the estimation of within effects in the hybrid model. Bonke (2005) showed that time use information is more accurate when obtained from diaries than when obtained from questionnaires. Therefore, the integration of time-diary data in large panel datasets could improve the quality of future research on this topic.

The hypothesis (H1) regarding the larger effects of housework on wages for migrant women than for migrant men is partially confirmed. OLS and the panel estimation models revealed significant differences in effects by gender for migrants. Nevertheless, in contrast to Hersch (2009), threshold effects could not explain the small or insignificant effects observed for migrant men. The effects for migrant men were insignificant when considering only those with one or two or more hours of housework per day. Because the housework variable considered only cooking, washing and cleaning on working days as household tasks, different types of tasks or different schedules, as suggested by Hersch and Stratton (2002) or Noonan (2001), could also not explain the gender differences in the effects.

In summary, the estimation results of this study showed significant negative effects of housework on wages for both migrant and native-born women. In addition to the examination of differences in effects by migration status, in an analysis of possible wage decreases due to housework, it is very important to consider differences in living realities. Ribar (2012) showed that time use is more gendered among immigrants than among native-born individuals in the sense that immigrant men tend to devote less time to housework than native-born men, whereas immigrant women tend to work more hours in the household than native-born women. The results of this study confirmed these outcomes. Considering the greater amount of time spent on housework among migrant women than among native-born women, a significant negative effect of housework on wages for migrant women as for native-born women leads to a greater wage decrease due to housework for migrants than for native-born women. Bonke et al. (2003) observed similar differences between Scandinavia and the US. Even high-income families in Scandinavia undertake more housework and do-it-yourself work than families in the US due to very compressed wage structures in Scandinavian countries and high tax levels that lead to a very high price of market services (domestic help, restaurant visits, etc.) or the non-existence of these services.

Conservative and right wing parties promoting immigration policies that reduce the influx of immigrants and refugees have gained in recent years in many countries with high vote shares. Already in 1964, Paul Samuelson demonstrated with a textbook model negative effects of an immigrant influx on the wages of competing factors, and following Borjas (2003), the assertion was politically motivated: “He was writing just before the enactment of the 1965 Amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act, the major policy shift that initiated the resurgence of large-scale immigration” (Borjas 2003, p. 1335). Empirical evidence for whether migration harms or improves the employment opportunities of native workers is extensive. The results have been mixed, but on average, the effects lie around zero, as also explained by migrants being imperfect substitutes for native workers (Brücker and Jahn 2011; Ottaviano and Peri 2012). Therefore, one can argue that rather than focus on economic problems due to migrants, politics should focus on problems of high inequality in society resulting from migrants’ problems of labour market integration. To increase labour market participation among migrants, an increase in female labour market participation is important, with wages being a significant incentive. The gender wage differential among full-time working migrants observed in this study based on German data was, on the one hand, lower than that among native-born full-time workers. On the other hand, considering the high selection of migrant full-time working women, the wage differential among migrants was excessive. The results further showed that the observed variables explained very little of the migrants’ gender wage gap, compared to that of native-born individuals. As Blinder (1973) emphasised, part of each wage differential is due to differences in objective characteristics, while another part remains even after controlling for such factors. Studies have criticised that the unexplained part of the gender wage gap decomposition cannot be interpreted as discrimination because estimations usually do not consider all of the (observed and unobserved) variables that affect wages and that are different between men and women (Heitmüller 2005). Nevertheless, for integration policy, it is highly relevant that hardly any differences in observable characteristics can explain the gender gap of migrants, compared to that of native-born full-time workers. The results indicated that human capital returns, including education and work experiences, were much lower for migrant women than for native-born women.

When studying the integration of (female) immigrants, economists have usually focused solely on labour market outcomes. In research on the gender wage gap, the consideration of housework has been a milestone. This study emphasised that the relationship between housework and earnings also has high relevance for the labour market integration of migrant women. In contrast to other observable variables, gender differences in housework time made a strong, positive contribution to the gap for both migrants and native-born individuals. On the one hand, this finding leads to the rejection of hypothesis H2 (which assumed differences by migration background). On the other hand, regarding the overall explained share of the gender wage gap, differences in housework time are much more relevant for migrants than for native-born individuals.

The main result of previous studies of this issue was that the time spent on housework was found to have a direct, negative effect on earnings, which was most pronounced for women. Drawing an optimistic picture, Hersch and Stratton (1994) indicated that younger women spent less time on housework and more time in the labour market. The authors assumed that such changes would decrease the gender wage gap in the future and lead to a more equal allocation of housework. Focusing on migrants, this study emphasised the need for integration policy to consider the still very large gender gap in time spent on housework among migrants. According to human capital theory, married women have, on average, more discontinuous employment histories and are less able to develop careers (Halfacree 1995). Women are therefore more often tied movers, leading to greater integration problems. Migrant women might spend more time on housework than their male partners due to lower earnings, higher integration problems and lower investments in country-specific human capital. The results of this study also showed that, in contrast to native-born individuals, individual-specific effects for migrants were uncorrelated with the housework variable. A correlation indicates that individuals, for instance, with greater productivity or more of a taste for work, specialise more in work and spend less time on housework. Social norms, gender role attitudes or the integration process in general might be an explanation. Migrant women’s greater time spent on housework establishes a vicious cycle by further decreasing wages, which we observed among the highly selected, full-time working migrant women in this study. Overall, the results suggest that the consideration of time spent on housework activities is important for the analysis of earnings as a primary incentive for the labour market integration of migrant women, and it provides general insights for the development and implementation of integration policies.

The study examined only the housework tasks of washing, cooking and cleaning and did not include childcare. Kimmel and Connelly (2007) found a positive correlation between female wages and childcare, in contrast to a negative correlation between female wages and other housework tasks. The authors assumed that, as employment time, childcare shares a strong investment component. Voßemer and Heyne (2019) further discussed whether childcare is not as undesirable as other housework tasks. Although the two types of tasks should therefore not be aggregated, for future research, it would be highly relevant to compare the separate effects of childcare on wages between migrants and native-born individuals, as well as to examine how the consideration of childcare changes or exacerbates the results.

For future research, an important additional question in this context is whether time spent on housework differently influences the types of jobs held by migrants and native-born individuals, with male-dominated jobs in general being associated with a smaller amount of housework time. Maume and Houston (2001) showed that women reported more work-family conflicts than men and that such reports increased with the long work hours that are often demanded in male-dominated jobs. Hersch (2009) showed that the effects of housework on women’s wages did not differ between different occupational categories. Because many migrant women are employed part time or irregularly, further research should also consider whether working part time reduces the negative effects of housework responsibilities. However, the aim should be to prevent wage decreases due to housework, rather than to reduce the paid working time of women.

References

Anastario, M., & Schmalzbauer, L. (2008). Piloting the time diary method among Honduran immigrants: Gendered time use. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(5), 437–443.

Anger, S., & Kottwitz, A. (2009). Mehr Hausarbeit, weniger Verdienst. Wochenbericht des DIW Berlin, 6(2009), 102–109.

Becker, G. S. (1985). Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(1.2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1086/298075.

Bellemare, M., Masaki, T., & Thomas, P. (2017). Lagged explanatory variables and the estimation of causal effect. Journal of Politics, 79(3), 949–963.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. NBER Working Papers Series, 21913, 1–77. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21913.

Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources, 8(4), 436–455.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Timm, A. (2003). Who marries whom? Educational system as marriage markets in modern societies. European studies of population. Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bonke, J. (2005). Paid work and unpaid work: Diary information versus questionnaire information. Social Indicators Research, 70(3), 349–368.

Bonke, J., Datta Gupta, N., & Smith, N. (2003). Timing and flexibility of housework and men and women’s wages. IZA Discussion paper, 860, 1–33.

Borjas, G. J. (2003). The labor demand curve is downward sloping: Reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1335–1374.

Brand, A., Bradley, M. T., Best, L. A., & Stoica, G. (2011). Multiple trials may yield exaggerated effect size estimates. The Journal of General Psychology, 138(1), 1–11.

Brücker, H., & Jahn, E. J. (2011). Migration and wage-setting: Reassessing the labor market effects of migration. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(2), 286–317.

Bryan, M. L., & Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2010). Does housework lower wages? Evidence for Britain. Oxford Economic Papers, 63(1), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpq011.

Carlson, D. L., & Lynch, J. L. (2017). Purchases, penalties, and power: The relationship between earnings and housework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(1), 199–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12337.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power for the behavioural sciences (Revised ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1208–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x.

Cooke, T. J., Boyle, P., Couch, K., & Feijten, P. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of family migration and the gender gap in earnings in the United States and Great Britain. Demography, 46(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0036.

Fortin, N. M. (2005). Gender role attitudes and the labour-market outcomes of women across OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3), 416–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/gri024.

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methodes and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202.

Giménez, J. I., & Molina, J. A. (2016). Commuting time and household responsibilities: Evidence using propensity score matching. Journal of Regional Science, 56, 332–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12243.

Halfacree, K. (1995). Household migration and the structuration of patriarchy: Evidence from the USA. Progress in Human Geography, 19(2), 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259501900201.

Hamermesh, D. S., & Trejo, S. (2010). How do immigrants spend their time? The process of assimilation. IZA Discussion Paper, 5010, 1–45.

Heitmüller, A. (2005). A note on decompositions in fixed effects models in the presence of time-invariant characteristics. IZA Discussion Paper, 1886, 1–11.

Hersch, J. (2009). Home production and wages: Evidence from the American time use survey. Review of Economics of the Household, 7(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9051-z.

Hersch, J., & Stratton, L. S. (1994). Housework, wages, and the division of housework time for employed spouses. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 120–125 Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred and Sixth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association.

Hersch, J., & Stratton, L. S. (1997). Housework, fixed effects, and wages of married workers. Journal of Human Resources, 32(2), 285–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/146216.

Hersch, J., & Stratton, L. S. (2002). Housework and wages. Journal of Human Resources, 37(1), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.248133.

Hirsch, B., & Konietzko, T. (2011). The effect of housework on wages in Germany: No impact at all. LASER Discussion Paper, 56, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-012-0119-5.

Jann, B. (2008). The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata Journal, 8(4), 453–479. https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.67672.

Keith, K., & Malone, P. (2005). Housework and the wages of young, middle aged, and older workers. Contemporary Economic Policy, 23(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/cep/byi017.

Kimmel, J., & Connelly, R. (2007). Mothers’ time choices: Caregiving, leisure, home production and paid work. The Journal of Human Resources, 42(3), 643–681. https://doi.org/10.2307/40057322.

LeClere, F. B., & McLaughlin, D. K. (1997). Family migration and changes in women’s earnings: A decomposition analysis. Population Research Policy Review, 16, 315–335. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005781706454.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., & Pellegrino, A. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016682213699.

Maume, D. J., & Houston, P. (2001). Job segregation and gender differences in work-family spillover among white-collar workers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22(2), 171–189.

Mincer, J. (1978). Family migration decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 86, 749–773. https://doi.org/10.1086/260710.

Noonan, M. C. (2001). The impact of domestic work on men’s and women’s wages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01134.x.

Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14(3), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.2307/2525981.

Ottaviano, G. I. P., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effects of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 152–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01052.x.

Phipps, S., Burton, P., & Lethbridge, L. (2001). In and out of the labour market: Long-term income consequences of child-related interruptions to women’s paid work. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 34(2), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/0008-4085.00081.

Reed, W. (2015). On the practice of lagging variables to avoid simultaneity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 77(6), 897–905.

Ribar, D. C. (2012). Immigrants’ time use: A survey of methods and evidence. IZA Discussion Paper, 6931, 1–42.

Schnuck, R. (2013). Within and between estimates in random-effects models: Advantages and drawbacks of correlated random effects and hybrid models. The Stata Journal, 13(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1301300105.

Schwarz, N. (2017). Der Wert der unbezahlten Arbeit: Das Satellitensystem Haushaltsproduktion. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Shauman, K. A., & Noonan, M. C. (2007). Family migration and labor force outcomes: Sex differences in occupational context. Social Forces, 85, 1735–1764. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0079.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economic, 70(5), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/258726.

Vargas, A. J., & Chavez, M. (2010). Assimilation effects beyond the labor market: Time allocation of Mexican immigrants to the U.S. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University.

Vella, F. (1994). Gender roles and human capital investment: The relationship between traditional attitudes and female labour market performance. Economica, 61(242), 191–211.

Voßemer, J., & Heyne, S. (2019). Unemployment and housework in couples: Task-specific differences and dynamics over time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81, 1074–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12602.

Zaiceva, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2011). Do ethnic minorities “stretch” their time? UK household evidence on multitasking. Review of Economics of the Household, 9, 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-010-9103-4.

Zaiceva, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2014). Children, kitchen, church: Does ethnicity matter? Review of Economics of the Household, 12, 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-013-9178-9.

Acknowledgements

I would like to specially thank Joyce Serido (the editor) for her helpful and constructive suggestions and guidance. I would also like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of participants in the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) lunch seminar and participants in the Asian and Australasian Society of Labour Economics (AASLE) Conference, the International German Socio-Economic Panel User Conference and the Australian Gender Economics Workshop. I would also like to thank Johann Ludsteck for helpful advice.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

The article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

Informed Consent

The used data obtained from the Socio Economic Panel is an anonymized dataset; the data user is not able to trace back information to individual participants. The personal data is processed in such a way that the rights of data subjects to the confidentiality and integrity of their data are not affected.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fendel, T. The Effect of Housework on Wages: A Study of Migrants and Native-Born Individuals in Germany. J Fam Econ Iss 42, 473–488 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09733-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09733-5