INTRODUCTION

još uvek maštam da neću zauvek biti ovde, kada mi se jedno jutro javi neki zapravo normalan muškarac. normalan muški izgled i život, posao, kola, otvorenog uma za putovanja i nova iskustva, pa idemo dalje. mada gledajući proklete sajtove od maštanja mrka kapa.

‘still dreaming that I won't be here forever, when an actually normal man contacts me one morning. normal male looks and life, a job, a car, open mind for travelling and new experiences, and we move on. although judging by the damn sites, no use of dreaming.’

This personal advertisement was posted in 2017 on the PlanetRomeo dating portal by a man from Serbia. In a simple, evocative style, the author depicts his dream of not being ‘here forever’, which ambiguously and perhaps deliberately refers to Serbia itself, his own life circumstances, or most likely, the gay dating sites setting. Most notably, globalised imaginary of a ‘normal life’ and the disillusioned imagination of an ‘actually normal man’ paired with the negative reference to dating ‘websites’ when using one captures the paradoxical and dynamic conceptualisations of ‘proper’ manhood in marginalised groups’ digital culture, which still escape full scholarly and activist understanding.

Without a doubt, mobile applications, chatrooms, and web-based personal ads have brought new possibilities for social participation and networking among gay men, remapping social space in revolutionary ways by opening it up for queer interactions (Borrelli Reference Borrelli, Balirano and Palusci2019), especially in the more traditional, patriarchal societies (Dang, Cai, & Lang Reference Dang, Cai and Lang2013). Still, a large portion of research on gay masculinity in online dating in fact points to the subculture's more complex power dynamics. Analyses have revealed contradicting exclusionary discourses which the genre naturalizes as ‘speaking one's mind’ (Shield Reference Shield2018), and which may range from sexual prejudice, microaggressions of ‘internalized homophobia’ (Shield Reference Shield2018), to racism and xenophobia (McGlotten Reference McGlotten2013). Titles like ‘I'm gay but I'm not like those perverts’, coming from recent research on Eastern European settings (Weaver Reference Weaver, Buyantueva and Shevtsova2020 for the above; Bogetić Reference Bogetić and Milani2018; Buyantueva & Shevtsova Reference Buyantueva, Shevtsova, Buyantueva and Shevtsova2020), precisely highlight the problems in approaching the conflicting orders of non-normative masculinities and their resonance in social reality.

An attempt to analyse the Serbian context only, or even the single ad above, in fact, runs into deeper difficulties in positioning an approach to masculinity. For one thing, the seminal theory of hegemonic masculinity (Connell Reference Connell1992) has come under pertinent criticism for how it conceptualises the two foundational axes: hegemony-subordination (an internal schema ranking masculinities with respect to one another), and authorisation-marginalisation (an external schema ranking masculinities according to external criteria, e.g. race or class). Just like the ad above, recent work on the discourses of (gay) masculinity suggests the two are not as neatly separable. Levon, Milani, & Kitis (Reference Levon, Milani and Kitis2016), for instance, show that masculinities in South Africa are strongly stratified in terms of race, with white masculinity positioned in the normative moral centre; Levon (Reference Levon2016) points to intersections of sexuality and religious identity, in voice quality indexical of commitment to religion despite identification with homosexuality. A growing body of analyses illustrates how representations of masculinity are shaped through parallel representations of gender, religion, age, class, and race (Baker & Levon Reference Baker and Levon2016; Shield Reference Shield2018; cf. Levon & Mendes Reference Levon and Mendes2016), whereby gay masculinity may often get situated across what is ‘actually normal’ or ‘not gay’ (L. Jones Reference Jones2018). The exclusions of online dating, as well as the yet undercomprehended pressures for ‘straight-acting’ (Milani Reference Milani and Preece2016) in nonheterosexual contexts, all highlight the relations of masculinity to these other axes, in ways that are fundamentally intersectional (Levon Reference Levon2015).

What is missing, then, are more fine-grained perspectives on the interconnections of the multiple out-group and in-group normativities that pave the ideological ground on which identities are negotiated in marginalised groups. As Hall, Levon, & Milani (Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019) recently argue, bridging this gap requires not only more attention to normativity, but also a more transversal turn looking at how multiple normativities are constructed crossways in interaction, with their inherent intersectionality and contradictions. Here I wish to call attention to the interaction of two processes in such transversal perspective, observable in the dynamics of self- and other presentation in sexually marginalised groups: the recursive intertwining of out-group and in-group values, and its normative and normalising effects. Irvine & Gal's (Reference Irvine and Gal2000) notion of recursivity, so far not deeply ensconced in sexuality studies, provides strong means to account for the tensions seen in the example above, when adopted in an intersectional perspective. It also allows us to account for what is somewhat simplistically referred to as internalised homophobia, by observing how recursive oppositions interact with multi-layered normalising patterns, in assimilation to heteronormative ideals. The ideological mechanism they produce, here termed recursive normalisation, merits attention as central to not only sexually marginalised groups, but, as I argue here, to the dynamics of marginalised identity (self-)presentation within larger structures of power in general.

The present article outlines this mechanism through a corpus-linguistic and discursive analysis of online personal ads and dating app texts written by gay men from Serbia. The findings reveal adversarial tensions around masculinity presentation, which centrally reflect recursive projection from one level of a relationship to another: the wider social opposition between negatively conceptualized feminine (and gay) characteristics and positively conceptualized masculine (and heterosexual) traits is transferred into the local gay digital landscape, intersecting with local values that range from modern urbanity to patriotism and national loyalty, all in assimilation to the ideal of the (heterosexual) male citizen. It is argued that this normalising logic, now becoming central to the globalising discourses on sexuality more broadly, highlights the problematic outcomes of neoliberal sexual politics centred on social assimilation. The findings support my broader underlying premise that analysing how queer linguistic and social practices interplay with the cultural presence of hegemonic heterosexuality and hegemonic masculinity—as well as of the broader systemic hegemonies and exclusions of the global political reality—is crucial to understanding the sexual/gender marginalisation and possibilities for change in this or any other local setting.

ONLINE DATING, ‘POSITIVE IMAGININGS’, AND NEGOTIATION OF NON-NORMATIVE MASCULINITIES

Personal ads

The personal ad can be dated back to at least the matrimonial newspaper columns in eighteenth-century Britain; in the face of later technological changes the genre has shown great adaptability, appearing also in telephone voicelinks, television text pages, and on internet sites. In the past several decades in particular, dating via print and online personal ads has gained immense international popularity, moving the private search for the desired partner into the public domain (Shalom Reference Shalom, Harvey and Shalom1997). Dating ads have thus come to stand out as a unique window into the ‘language of love’ (Groom & Pennebaker Reference Groom and Pennebaker2005), and scholars have increasingly recognized them as a source of insights both for the study of genre and for the sociocultural study of desire, sexual identities, and ideologies (e.g. Milani Reference Milani2013; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2015).

In analyses of newspaper dating advertisements, the personal ad has been described as a genre aimed at establishing a link with readers, by engaging them in a kind of ‘ “do I fit?” dance with the text’ (Shalom Reference Shalom, Harvey and Shalom1997:187). Constraints associated with cost and word length mean that print ads have existed as a minimalist genre (Nair Reference Nair and Toolan1992), in which people create short and selective descriptions to be presented to the public. The end result, described in numerous studies on the subject, are fairly ‘straightforward declarations of what one is and what one wants’ (Deaux & Hanna Reference Deaux and Hanna1984:363). Typically, these declarations follow a highly conventionalized structure that could be described as follows (Coupland Reference Coupland1996).

1. ADVERTISER

2. seeks

3. TARGET

4. GOALS

5. (COMMENT)

6. REFERENCE

e.g. Not unattractive male, 53, insolvent, into theatre, writing, music, cooking, wining and dining seeks female 35–40 for fun and friendship. Box111.

More specifically, in her seminal study on UK paper/teletext ads and their voicelink counterparts, Coupland starts from an understanding of dating ads as a limiting case for the discursive construction of identities, that requires very direct, or ‘straightforward’, self- and other-descriptions within a sparse textual framework. She observes that most ads in her corpus follow the sequential structure shown above, almost invariably containing elements 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. She notes that the COMMENT slot presents a fleeting opportunity to deconventionalize the genre, but that this opportunity typically remains unused. Coupland further stresses the personalizing strategies used by ad authors for self-presentation, but nevertheless notes that the conventionalized structure of ads provides limited opportunities for advertisers to be creative (see also Nair Reference Nair and Toolan1992; Shalom Reference Shalom, Harvey and Shalom1997).

In one of the first studies of personal ads in gay men's context, R. Jones (Reference Jones2000), however, observes that in his corpus of Hong Kong ads this sequential structure is somewhat less conventionalized, though the differences he lists seem to include minor departures from a relatively ordered structure (eg. a tendency to present search for TARGET in the passive voice). Still, Jones makes the important point that even given identical constraints, various social and cultural forces can impact text structure in this genre, which in turn reflects and constrains the presentation of gender identity. In any case, overall, despite the usually simplified and commodifying text, personal ads hinge on the ability of authors and readers to encode and decode a personal fantasy of romantic involvement, through the typically appealing future interactions evoked in an ad. Indeed, such ‘positive imaginings’ (Thorne & Coupland Reference Thorne and Coupland1998:254) are crucial in determining the response and follow-up to an ad (Shalom Reference Shalom, Harvey and Shalom1997).

Similar characteristics concerning sequential structure, straightforwardness, and ‘positive imaginings’ have been noted in studies of web-based personal ads (e.g. Zahler Reference Zahler2016), though research on online personals as yet remains comparatively scarce. Some important differences from print ads noted in the literature include lack of word-length/cost constraints (Borrelli Reference Borrelli, Balirano and Palusci2019), absence of geographical limitations (Bakar Reference Bakar2015), possibility of instant establishment of contact through features like chat or email (Wu & Ward Reference Wu and Ward2018), as well as specific language and proliferation of novel abbreviations that can serve as code (Vanderstouwe Reference VanderStouwe2019). While in these respects personal ad sites are similar to other computer-mediated modalities (e.g. chatrooms: King Reference King, Jones, Chik and Hafner2015; or cybersex: R. Jones Reference Jones2008), they differ from other online settings in their inherent anticipation and targeting of offline face-to-face encounters (Milani Reference Milani2013), though, again, the online-offline contact goals are more blurred in reality (Race Reference Race2018).

Mobile-based dating applications

Apart from the dating sites, mobile device applications are becoming increasingly popular platforms for social and sexual encounters, especially among gay men. Unlike dating sites, where weeks or months will often pass before face-to-face contact, ‘location-based real-time dating’ (LBRTD) applications (Handel & Shklovski Reference Handel and Shklovski2012; Davis Reference Davis2018) are focused on immediacy and prompt encounters. Specifically, they allow the chains of ‘response – followup – meeting’ to be multimodal and also within a dramatically shorter timespan compared to website ads, so meeting can virtually take place within minutes from the act of advertising a profile (Borrelli Reference Borrelli, Balirano and Palusci2019). As they are accessed primarily via mobile devices, they allow contacts to be formed outside of the more private social spaces, at any time and in any location.

As Blackwell, Birnholtz, & Abbott (Reference Blackwell, Birnholtz and Abbott2015) note, LBRTD apps are unique not just because they are mobile-based, but also in their use of fine-grained location information for identifying nearby users. In many of these apps, strangers can be located based on geographical proximity, without the need to identify existing contacts or place names (Blackwell et al. Reference Blackwell, Birnholtz and Abbott2015). This is of note, firstly, in the very default logic of hook-up devices. As Race (Reference Race2015) explains, isolating proximity over other determinations as a primary reason for contact can frame sexual encounters as ‘no strings’ and commitment-free, unlike the complex algorithms in dating websites aimed at the heterosexual market. Secondly, this very form of geolocative communication is of note in that it in many ways steps out beyond socially defined places. Blackwell and colleagues (Reference Blackwell, Birnholtz and Abbott2015:2) further argue that ‘this ability to identify and meet nearby [gay men] in ostensibly “straight” or not otherwise sexualized spaces raises novel questions around presentation and perception of identity’, as well as the future of interactions within gay spaces in general (see also Wu & Ward Reference Wu and Ward2018). In other words, the use of these apps can be seen as leading to a remapping of social space which makes the public sphere less heteronormative (Batiste Reference Batiste2013), opening it up for queer interactions.

Given the emphasis on prompt social and sexual encounters, LBRTD profiles typically contain more concise and more spatially constrained personal information than that given in personal ads. Most profiles are visually dominated by the photo, with a list containing physical traits (height, weight, race), interests (e.g. friends, chat, dates), and geographic distance from the user. The photos themselves are now usually reviewed by a team of screeners before being posted, based on a published set of guidelines (Davis Reference Davis2018). In a short text blurb (usually not longer than fifty words) users can say something about themselves and the desired partners, in ways similar to personal ads. The content of these blurbs, however, appears to be more concise and less structured than in the ads as described in Coupland (Reference Coupland1996).Footnote 1

Initially, many of the most popular apps of this type were apps for seeking immediate sex (Mowlabocus Reference Mowlabocus2012), but they are nowadays coming to be used for more social purposes. Blackwell and colleagues (Reference Blackwell, Birnholtz and Abbott2015) attribute this to the fact that the user base of these apps has expanded greatly, but also to commercial reasons, such as vendors viewing sex-seeking apps as unwanted. More recent studies, however, highlight the inadequacy of such oppositions, stressing the interaction of app functions (e.g. merely ‘checking-in’ at a location), and showing that domains of sexual and social experience overlap through gradients in practice (see Race Reference Race2018).

Overall, interactions built around online dating spaces, be it personal ads or mobile apps, nowadays represent particular kinds of communicative activity among gay men that can be taken as new forms of social and sexual practice in their own right (Race Reference Race2015, Reference Race2018), and ones that may indeed create alternative realities to the oppressions experienced by these people in everyday interactions (eg. Duguay Reference Duguay2016). The predominance of male users of these websites can also be seen as a reflection of the centrality of casual sex in many gay male subcultures (Altman Reference Altman2013), which is curbed in mainstream society. While dating sites have earlier been described as opening up less rigid spaces for the construction of sexual subjectivities, it has also become clear that their intersectional and normative nature, as well as the complexity of their ‘community’ building outcomes, means they do not simply drive more fluid gender representations forward in some straight-line manner. In the analysis that follows, I highlight their more complex dynamics of subversion and resistance by outlining the mechanism of recursive normalisation.

CONTEXT, DATA, AND METHOD

Serbia can be seen as one example of a society in which digital communities are altering queer interaction, operating within a specific local context. In this postsocialist, pre-EU accession locale, the discourses of patriarchy and national tradition have formed complex intersections with the discourses of the modern global citizenship, ‘on the way to Europe’ (Musolff Reference Musolff, Musolff, Good, Points and Wittlinger2017). In the past decade in particular, as debates on gay rights and the Pride parade got more public prominence, sexuality appears to have gained significant symbolic value in relation to citizenship, and particularly in imagined opposition to nationhood (Canakis Reference Canakis2018). In everyday settings, doubtlessly, concerns with inequality, including physical and social threats, continue to form an important part of the social reality of gay men in the country. Though the position of sexual minorities has over the past decades partly improved both in the legal and social spheres (homosexuality has been decriminalized, and there is a growing number of gay activist groups, clubs, and party events, though mostly confined to the capital city), LGBTQ individuals continue to be among the most discriminated social groups in Serbia.Footnote 2 In this context, the mushrooming national and international dating sites form complex and rapidly shifting ground for the construction of non-normative sexual identities, in a comparatively ‘safe’ space that may variously shape this minority subculture and its negotiations of non-normative masculinity.

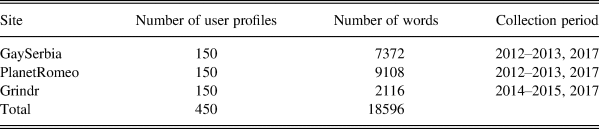

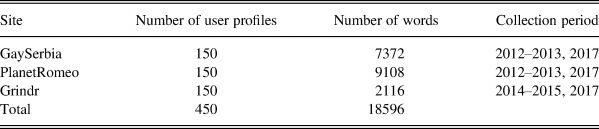

The data used are composed of personal ads taken from the GaySerbia and PlanetRomeo websites, and user profiles from the LBTDR app Grindr.Footnote 3 For study purposes a specialized corpus was designed (18,596 words in total), composed of profile texts from the three platforms taken together, with a brief comparison also given in the final section of the analysis. In personal ad sites, the initial sample of ads was randomly selected in equal numbers (150 total) from the two sources in two rounds of data collection; ads containing only the default personal statistics without a textual description were excluded from the data collection. Only ads written by men who specified seeking male partners were considered, and only ads written in the Serbian language were retained.Footnote 4 The Grindr subcorpus also includes 150 profiles, randomly selected and supplied to the author by two users;Footnote 5 again, only profiles with text and written in Serbian were retained in the analysis. Sample details are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample details.

The two websites used for the study are the most popular dating and entertainment websites among the Serbian LGBT community. GaySerbia is a specifically Serbian site, launched in 2000. It offers a variety of content, but the ads are among its central elements and graphically take a visible place on the home page. At the time of writing, the site contains about 11,000 ads. In order to post or read ads, authors must first register at the site; registration is free and involves no minimal age requirements. To access the ads page, users specify their own gender and the preferred gender of the partner, with the optional choice of partner's age, country of residence, and purpose of meeting (friendship, love, sex). PlanetRomeo offers a similar format for personal ads, though some major differences must be noted. Firstly, the site is intended specifically for male users. Secondly, PlanetRomeo is an international site, though search can be limited based on a single country. Of the site's over one million users, about 12,000 are currently registered from Serbia. Also, on PlanetRomeo, chat is directly linked to users’ profiles, while on GaySerbia it is a separate function, which contributes to somewhat greater interactivity of PlanetRomeo compared to GaySerbia.

Grindr is an international mobile geosocial networking application designed to connect gay men, released in 2009. Based on the user's location, the app calculates the proximity of other users and displays their profiles in order of proximity. Users must first register to use the app, and the process of registration is relatively simple and free. Upon signing in, the user sees a list of profile pictures (up to 100) of nearby users. Profiles are accessed by tapping on user photos, and include a headline, a short text blurb, physical traits (height, weight, race), interests on Grindr (friends, chat, dates), and geographic distance from the user. At the time of writing, Grindr has more than five million users in 192 countries.

My analysis is informed by the discourse-analytic and corpus-linguistic approach to the profile texts.Footnote 6 The corpus linguistic methods, though widely used and here kept simple, need a brief description given that they both concern a low-resources Slavic language, and are instrumental in an ideology-focused work.

The techniques and processes used in the corpus-linguistic (CL) analysis involved keywords and collocation analysis. AntConc software (Anthony Reference Anthony2019) was used. The first step in the analysis was the identification of keywords, that is, the words whose frequency is unusually high in comparison with general language texts; their calculation means comparing the frequency of each word in the main, smaller of the two wordlists (the dating corpus used) with the frequency of the same word in the reference wordlist. Keyword analysis presented some difficulties, mainly due to the morphology and limited resources for the Serbian language that could serve as a reference corpus. Specifically, the obtained wordlists required extensive lemmatization (annotation of base forms, like Eng. them-they), given the complex morphology of Serbian. Lemmatization was conducted using BTagger (Gesmundo & Samardžić Reference Gesmundo and Samardžćžić2012), as one of the few taggers that successfully deal with Serbian data. Keywords were then calculated using the lemma list from my study corpus, and a lemma list based on a general corpus of modern Serbian (see Vitas, Krstev, Obradović, Popović, & Pavlović-Lažetić Reference Vitas, Krstev, Obradović, Popović and Pavlović-Lažetić2003). The reference corpus from which the lemma list was taken contains about 100 million words, written texts from contemporary Serbian language. Keywords were generated using the log-likelihood method.Footnote 7 Overall, while these choices could not be ideal, it was assumed that keywords would still be plausible indicators of ‘aboutness’; moreover, some researchers have shown similar keywords to be elicited regardless of the reference corpus one chooses (e.g. Scott Reference Scott and Archer2009; Goh Reference Goh2011). The technique was mainly used to identify which descriptors of gender/sexual identity are key in the corpus, and to explore these through collocation analysis, and importantly, further qualitative analysis.

The second CL technique used is collocation analysis, which was used to further explore some meanings of the lemmas of interest returned in the keyword list. The scope for collocation was limited to five words to the left and right of the node (following Sinclair Reference Sinclair1991). The collocates obtained in AntConc were then annotated, that is, the lemmatization of individual collocate forms was again performed to accurately sort out all the inflected case forms of the same words (which made it possible to examine the frequencies of collocate lemmas). The present analysis adopts nonstatistical, collocation-via-concordance methods. Given the topic specificity and the small size of the corpus, as well as some observed difficulties with statistical calculation of collocations, hand-and-eye techniques were found to be appropriate and more practical.Footnote 8

The corpus findings served as a basis for further qualitative analysis, in the tradition of (critical) discourse analysis (Van Dijk Reference van Dijk1992; Fairclough Reference Fairclough2013). While the term discourse has taken on multiple senses, it is here understood not only as language in context or ‘language in use’ (e.g. Brown & Yule Reference Brown and Yule1983), but also in the poststructuralist, Foucauldian sense as ‘practices which systematically form the objects of which they speak’ (Foucault Reference Foucault, Foucault and Gordon1972:49). From this perspective, the focus is on cultural systems of knowledge, belief, and power (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2003), but in a position that is nevertheless compatible with a language-oriented study of discourse, as best exemplified in the critical discourse analysis tradition.

The material used must be seen as linked to a specific online social space, and not generalised to all gay men, or gay men in Serbia. Also, while the two data sources (personal ads and mobile app profiles) impose some different constraints on users, they are used for similar instrumental purposes in the online context; exploring them together is expected to be productive in light of goals in this study, but a separate section will also give a brief comparison of the personal ad and mobile app patterns. The genre differences should nevertheless be borne in mind, especially given the information contained in the more ‘automated’ profile segments in apps that must remain outside the analysis.

The approach necessarily opens up many questions related to ethical considerations in using this type of data. While social networking sites present unprecedented possibilities for sociolinguistic research, by virtue of being public and free to access, arguably this need not mean they are public forums (King Reference King, Jones, Chik and Hafner2015). In sexuality research, these questions are all the more relevant, as they involve face and safety risks for those involved. Still, discussions of research methods have not been widely addressed in the field (see Mortensen Reference Mortensen2015). In online social spaces, local norms of access and visibility need to be considered, and the major issue is whether the information posted can be considered public or not (see Buchanan Reference Buchanan, Consalvo and Ess2011). To some extent it makes sense to acknowledge that in sites like PlanetRomeo or Grindr, like in many of the popular networking sites in general, users reveal information to strangers and include the possibility that these strangers are not just desirable partners, but any strangers with any browsing purposes (Solberg Reference Solberg2010);Footnote 9 the need to register prior to browsing, however, reminds us this is not as simple a point. While the perspectives are surely debatable, anonymity remains crucial for preserving the users’ identities. With this in mind, all pseudonyms used have been anonymized and changed in ways that resemble the pseudonym styles of the sites.

KEYWORDS: A GLIMPSE AT KEY CONCEPTS AND GENDER/SEXUAL IDENTITY LABELS

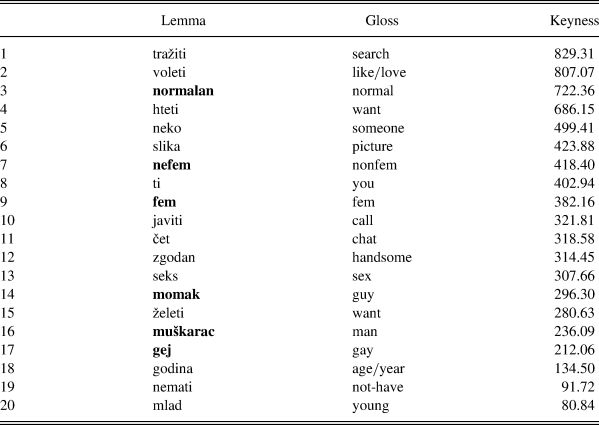

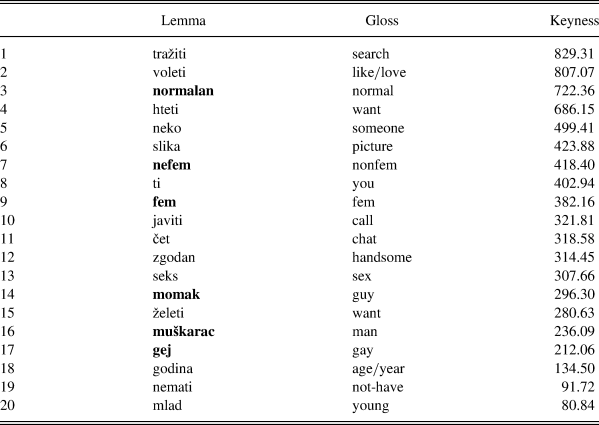

Identification of keywords was the first step in the analysis, revealing possible patterns of usage which can then be investigated more thoroughly, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Top twenty lexical keywords.Footnote 10

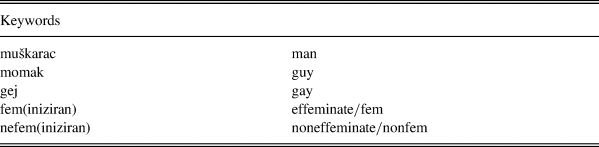

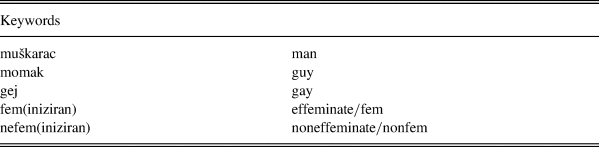

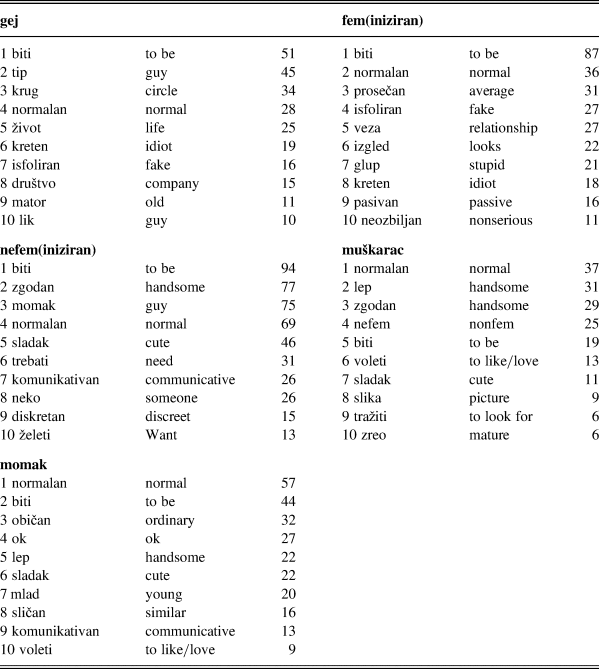

Many of the keywords, such as seks ‘sex’ or čet ‘chat’ are not surprising given the type of data. One of the top positions, interestingly, is taken by the adjective normalan ‘normal’, which hints at great relevance of normative discourses in this social space. As the following analysis gave further cues to its use and meaning, central to the process discussed in this article, these are discussed in a separate section. In particular, a subset of the keywords (e.g. muškarac ‘man’, gej ‘gay’, feminiziran ‘effeminate’) are to do with sexual/gender identities, including general labels, appearance, and behaviour, the representations of which are the focus in this study. The key terms to be analyzed further are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Sexual and gender identity keywords.

For further collocation analysis, the decision is made to code fem and its longer variant feminiziran ‘fem/effeminate’ as one search item, as it represents one identity label with little difference in stylistic or social meanings (unlike e.g femmy/femi that appears in a couple of instances, with a diminutive and mostly ironic/pejorative sense). The collocations for fem and feminiziran were indeed found matching in a preliminary analysis that treated them as separate.

COLLOCATION: GRAMMATICAL WORDS AND PATTERNS OF DISTANCING

Collocation analysis overall reveals the subtle linguistic strategies that work to realise the concept in focus: othering and distancing from the prototype, blurring the boundaries, recursive evaluations via associated evaluative concepts, and relational normalisiation of particular gay identities. The concepts of recursivity, intersectionality, and normativity central to recursive normalisation are examined in relation to these specific patterns first, and discussed more broadly in the final section.

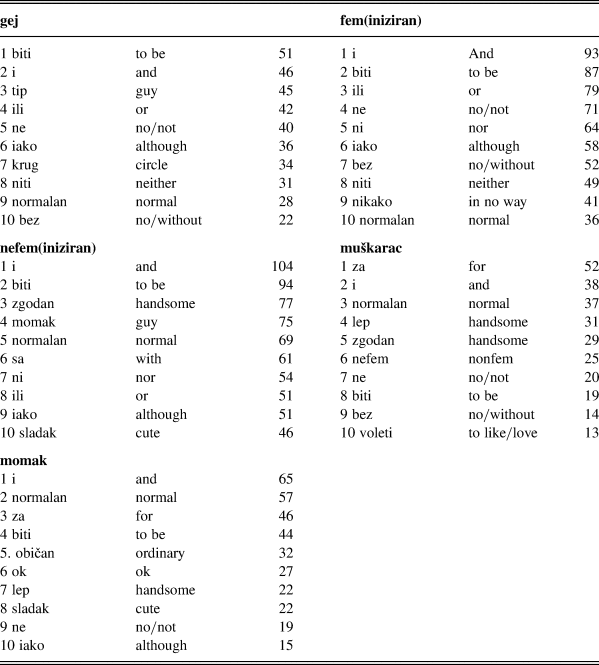

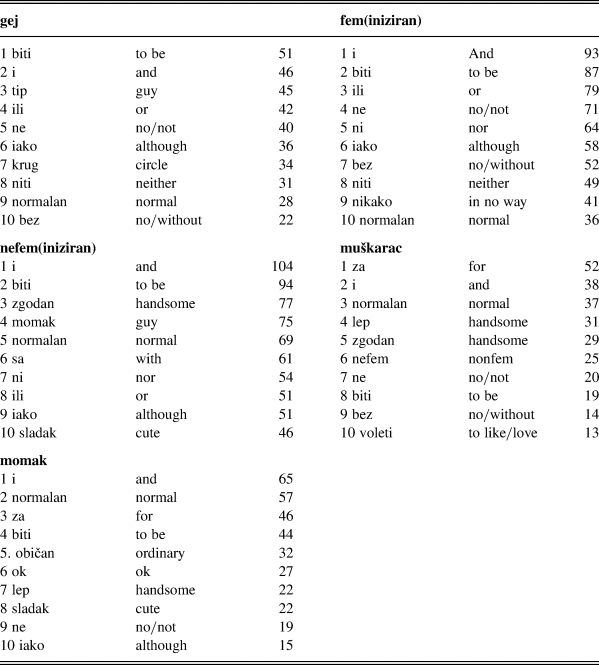

To begin with, most of the top collocates for each of the selected keywords are expectedly grammatical words. (see Table 4) While grammatical words are often excluded from discourse-oriented analyses, a more careful observation suggests that these are telling both of some important linguistic characteristics of the profiles, as well as precisely of the discursive strategies of self- and other-masculinity positioning.

Table 4. Top collocates of the gender/sexuality keywords.

Firstly, i and ili (‘and’ and ‘or’) are among the top collocates of the node words. They point to tendencies of coordinated descriptions in dating profiles, here often including five, ten, or even more coordinated adjectives and nouns—for example, ne stariji od 30 god, inteligentan – pametan – obrazovan, pedantan, NEFEM. uz sve to PRIVLAcAN, simpatican, sladak i na kraju VJERAN i samo MOJ!!! ‘not over 30, intelligent – smart – educated, pedantic, NONFEM as well as ATTRACTIVE, likeable, cute and in the end FAITHFUL and only MINE!!!’. A feature of personal ad style, coordinated descriptions provide a concise focus on the possessed and desired traits. Such format is evocative of the old newspaper personals, but it gains new stylistic value in platforms where no word length constraints are present. Importantly, however, presentation of this type gains currency through the specific associations between the multiple concepts listed (e.g. the near synonyms of intelligent, smart, educated, or the linked NONFEM and ATTRACTIVE). Coordination is thus not just a feature of style, but an important established strategy by which the value laden lists are presented and developed in the in-group context. The specific patterns of this process can be understood through collocation analysis, explored in the next section, but also through overlapping with other subtle strategies that realise recursive normalisation, as discussed in the rest of this section.

Importantly, the other repeated collocates ne, bez, iako reveal a pattern of negating, or distancing from certain forms of self-presentation and identity to be a major aspect of ad content. In particular, the dominance of negative ne-biti/ne/ni/niti ‘not-be/not/neither/nor’ descriptions is observed. Consider for instance the following ads, where each clause or descriptor contains a negation in this form.

(1) Petarr (37, PlanetRomeo)

Klinci ispod 20 ne, sakupljaci slika ne, feminizirani ne, neozbiljni ne.

‘Kids under 20 no, picture collectors no, effeminate no, non-serious no.’

(2) Taylr (20, Grindr)

Makar da ne stavljaš gole slike, da nisi feminiziran, niti u gej priči primarno tj nije ti samo gej društvo

‘At least you shouldn't post naked pictures, you should not be effeminate, (n)or in the gay world primarily (n)or having just gay friends.’

Negated descriptions, often in coordination lists, can serve the practical function of concisely presenting the unwanted (e.g. (1)); they often entail more elaborate descriptions negotiating the desired and the appropriate, built around repudiation of the ‘fem’ or ‘typically gay’ traits and behaviours (‘being in the gay world primarily’ in (2)). There is similarity to be observed, in fact, between these kinds of repudiated masculinities and the existing accounts of heterosexual masculinity construction (e.g. Kiesling Reference Kiesling, Coupland and Jaworski2009), in their essentialized gender difference and undermining of connections to femaleness. Specifically, much like the patterns in heterosexual interactions (Kiesling Reference Kiesling, Coupland and Jaworski2009) for avoiding assumptions that one may be gay, the negation patterns in the profiles reflect strategies for avoiding assumptions that one may be fem, ‘too gay’, or ‘gay gay’.

(3) Gamma (26, GaySerbia)

Običnog izgleda, sportski tip, seksom opsednut, ne gej gej po izgledu :D

‘Ordinary looks, sports type, sex-obsessed, not gay gay in appearance :D’

Further, a related pattern of distancing is evident in the pervasiveness of the bez ‘without/no’ format, allowing concise, list-like descriptions. Bez is a common collocate of fem(iniziran) in particular, but also of gej.

(4) Taylr (18, Grindr)

Bez matorih, bez feminiziranih, bez napaljenih koji bi susret na pet minuta

‘No old guys, no effeminate ones, no horny ones looking for a five-minute hookup’

(5) MXX (20, PlanetRomeo)

molim vas bez:

– gej/strejt fejsbuka i tih fora

– “strejt”batica za drkanje i ortački oral pošto tu jelte nije ništa gej, jer je ortački

– isfeminizaranih karleušasekacecaitd tetkica,nemam ništa protiv ali just no

– nekulturnih, nepismenih (ne voliš i newolis nije i nikada neče biti isto)

– likova koji po godinama mogu da mi budu roditelji

– veza za jednu noć, not my thing

‘please no:

– gay/straight facebook and those things

– “straight”dudes for jerking off and buddy oral since there's nothing gay about that right, as it's for buddies

– effeminate karleusasekacecaetcFootnote 11 queens, I've got nothing against them but just no [English]

– crass, illitarate people (ne voliš and newolis is not and never will be the same thing)

– guys who could be my parents by age

– one-night stands, not my thing [English]

I don't quite follow how things work around here and I couldn't give a fuck to learn’

Along with the target keywords, we see that the scope of bez encompasses a range of concepts, sometimes including ironic stylizations of ‘unwanted others’, or just presenting lists of undesirables that can involve anything from gender presentation to ‘verbal hygienist’ comments (Cameron Reference Cameron2012; cf. Bogetić Reference Bogetić2016) about ad writers’ bad grammar (as in (5)). In (5), the author combines the names of three Serbian female pop-folk singers, Jelena Karleuša, Seka Aleksić, and Ceca, traditionally associated with poor cultural taste. Repeated locally salient references to urban/rural, modern/traditional, ‘cultured’ and ‘uncultured’ actually play a specific part in the local construction of valued masculinities, as further discussed in the section on lexical collocation. Centrally, still, the collocation pattern of bez with feminiziran and gej reflects distancing from nonmasculine gay identities and from making sexuality an important aspect of one's life.

The linguistic strategy has a specific effect compared to other types of negation, which may explain its prominence in the data: it works via a categorical tone, stressing that little further description is needed, that the meaning of the bez part is culturally understood. The connotation of such authority-infused, common-sense negation also allows the interpretation of some very short texts that solely use the bez + noun phrase format (e.g. Bez pederske priče, tačka ‘No fag story, period’ or Bez feminiziranih ‘No effeminates’), evocative of authoritative, unquestionable signs like ‘No talking’ and ‘No littering’.

The above examples also show departure from the sequential structure described by Coupland (Reference Coupland1996) and attested in other studies; overall, the definition of online dating texts as ‘straightforward declarations of what one is and what one wants’ appears inadequate for describing my data. As patterns of negation show, these texts could more adequately be described as ‘declarations of what one is not and, especially, what one does not want’. Still, the descriptions are not merely descriptions of desired looks and style, but involve complex recursive evaluation and often full blown theorising of (in)appropriate gay masculinity that largely rests on existing, heterosexist gender ideologies.

However, that the process described is more complex and not merely a translation of outside values, but a recursive refraction always laden with some tension and negotiation, is best seen in the analysis of the grammatical collocate iako. Distancing via iako ‘although’, in the common concession clause format, is another major strategy, one that works as a specific kind of opposition, reconciling the irreconcilable, connecting the kinds of masculinities socially constructed as oppositions and here negotiated as potentially inclusive. One user even makes it explicit in a meta-comment in (6).

(6) Zak (30, PlanetRomeo)

Budi obicno musko iako si gej, nije to tako nemoguce valjda

‘Be an ordinary male even though you're gay, it's not that impossible I guess’

Specifically, iako appears as a collocate of gej and feminiziran referring to desirable traits despite being gej or fem in (7) and (8) below; its occurrence with nefem again emphasizes the notion of masculinity despite being on the (repeatedly negatively represented) dating sites (e.g. (9)).

(7) DredC (34, PlanetRomeo)

Budi muško iako si gej.

‘Be a man even though you're gay.’

(8) ajax (18, Grindr)

Zgodni, slatki, sređeni dečaci, čak iako fem; D

‘Handsome, cute, well dressedboys even if fem; D’

(9) dmn (22, Gayerbia)

Samo da zi normalan, nefem iako si u prokletom ovom akvarijumu

‘Just be normal, nonfem even though in this bloody aquarium’

In ‘the [positive-ordinary-male] although [of non-normative sexual identity]’ representation, the concession pattern reflects a subtle linguistic strategy that works to normalise particular gay identities. Masculinities are here negotiated by simultaneously adopting the established social oppositions between the valued heterosexual and devalued gay identities, as well as constructing nonmasculine traits and non-normative masculinities as within the realm of the prized. Such descriptions thus often go in confusing multiple directions that index a kind of thinking on the run.

(10) PP (29, PlanetRomeo)

Iako gej i za neke malo fem sam normalan muskarac sa normalnim zivotom za sve vas sa nefem stop prvo upoznaj osobu ne moram biti totalni peder samo iako sam malo fem i nenapucan

‘Although gay and a little fem for some I'm a normal man with a normal life for all you with nefem stop meet the person first I needn't be a total faggot just though I am a little fem and nonmuscular’

The run-on description, at first glance almost ungrammatical, uses the concession format to situate notions of a ‘normal man with a normal life’ within the notions of being ‘gay and a little fem for some’, which are essentially opposed in the wider gender-ideological system. The intertextual interaction with other profile texts points to negotiation and co-construction of appropriate masculinity, as a dynamic process, which both rests on existing shared knowledge and constructs new shared knowledge for future interactions (cf. McConnell-Ginet Reference McConnell-Ginet, Ehrlich, Meyerhoff and Holmes2014).

Quantitatively, a further check does confirm these grammatical patterns for each of the observed keywords (since collocates are defined at ±5 word span from the node keyword, and could reflect different grammatical relations)—all of the keywords more often (and nearly 80% for gej and fem-iniziran) appear in negation and concession, while less than 45% overall are in affirmative form without concession (mainly with muškarac and momak). The common negation, and distancing from the gej properties may seem surprising in a self-identified gay community, but confirms the recursive repudiation of gay identities that is nevertheless dynamically negotiated in specific ways.

Going back to the main point, the rejection of particular gay masculinities indexed by patterns of grammatical collocation is a major strategy of recursive normalisation. It reflects an important social mechanism by which core members of a marginalised community may often be othered as marginal within the in-group context, in view of being the ‘prototypical’ representatives of a socially deligitimized identity. Other marginalised identities can, then, be normalised by being positioned on the scale as further away from the prototype and closer to the dominant norms. In examples like the above, or negations that make the point quite explicit (Ako nisi prototip pedera, javi se pa da vidimo ‘if you are not a prototype faggot, contact me and let's see’; Ako si gej ne moras da izgledas ko sa naslovne strane nekog pederskog casopisa ‘Though you are gay you do not have to look like a cover of some faggot magazine’) the out-group heteronormative insults are recursively adopted inwards, though with a web of in-group meanings that range from playful ‘fag’ naming, through explicit negotiations and most notably normalisation through distancing and othering. The mechanism, especially its element of normalisation towards established values, becomes clearer in the analysis of lexical collocates and their evaluative meanings.

COLLOCATION: LEXICAL WORDS AND RECURSIVE ASSOCIATIONS

Lexical collocates point to further patterns of association, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Top lexical collocates of the gender/sexuality keywords.

Clearly, the collocates of gej and fem(iniziran) include adjectives carrying strong negative evaluation, such as kreten ‘idiot’ or isfoliran ‘fake’, while the top collocates of nefem(iniziran) are predominantly positive.

(11) Dulke (19, GaySerbia)

pitaj sta zelis, neozbiljni, fem, pickice i pedercici neka me zaobidju

‘ask what you want, those who are not serious, fem, pussies and little faggots stay away from me’

(12) GXX (21, PlanetRomeo)

Neko komunikativan, zgodan, nefeminiziran, ne tražim previše. Sam sam mlad, razvijen, nefem, siguran u sebe, moderan ali ne metro, Srbin od rodjenja pre svega.

‘Someone communicative, handsome, noneffeminate, I'm not asking too much. I am young, well built, nonfem, self-confident, modern but not metro, a Serb since birth above all.’

(13) Ali (31, PlanetRomeo)

Nefem, razvijen, sportista, živeo u Evropi u Nemačkoj, nagledao se i ljudi i sveta i lepog i ružnog, a ostao sasvim običan muškarac. Samo da nisi fem ni ljakse na kakve samo nailazim u poslednje vreme.

‘Nonfem, well built, sportsman, lived in Eurpope in Germany, has seen a lot of people and the world and the beautiful and the ugly, and remained a totally normal man. Just don't be fem and a peasant like I have only met here recently.’

The common listing of coordinated qualities includes nefeminiziran along with other positive qualifications, or the use of fem and gej with highly pejorative heterosexist qualifications (fem, pickice i pedercici ‘fem, pussies and little faggots’ in (11)). The lists of diverse coordinated adjectives, almost as if ‘not to miss anything’, include a set of defining traits built around good looks, physical fitness, strength, confidence, as general external ideals of masculinity. At the same time, however, they also include locally salient values that concern modernity, tradition, nation, the urban, and the rural, which are recursively refracted from the broader Serbian society in ways we might not expect in this type of genre. For example, references to Europe (i.e. European Union), the west, such as Germany in (13), are used to emphasise not only life experience, but a specific type of worldly persona in crucial opposition to the traditional, rural type, indexed here by the pejorative slang ‘ljakse (seljak ‘peasant’) in the second part of the ad. This indexes identities and ideologies which have been locally salient in both the postsocialist and imagined ‘transition’ discourses of the country, and which then intersect with ideals of physical appearance and recent trends such as the ‘metrosexual’ look. Long coordinations and struggles around precise definition, in particular, show how these values get constructed in very specific ways in relation to desirable gay masculinities (compare e.g. ‘but I remained a totally ordinary man’ in (13), or being ‘modern’ but not ‘too metro’ in (12), where ‘metro’ is locally often constructed as a nonmasculine western trend).

Example (12) above illustrates the associations between nefem and positive personal characteristics, but also points to another intersecting value, that of national belonging and patriotism. Similarly, analysis of the negative positioning of gej shows that it intersects with other local social and political discourses, in ways that sometimes challenge existing conceptualizations of globalized gay culture. Note another similar point built around a negative collocating of ‘gay idiots’.

(14) Toma (32, PlanetRomeo)

Znam ko sam i odakle sam, patriota i ponosan na to. Porodica i zemlja su duh koji poštujem a ne sprdam se kao neki ovde, pa europski nalickani gej kreteni me mogu zaobici

‘I know who I am and where I am from, a patriot and proud of it. Family and country are the spirit I respect and I do not mock it like some people here do, so european dressed up gay idiots can stay away from me’

Similarly to the post in (12), Toma's text illustrates the presence of local traditional discourses of patriotism and familial loyalty, where the idea of the spiritual ‘duh’ plays an increasing part (see Čolović Reference Čolović2013). In examples like this one ‘european dressed-up gay idiots’ are a more distinct subgroup to be distanced from, within a broader rejection of the globalizing and Europeanizing influences that have otherwise taken on symbolic value in Serbian gay rights activism. In particular, the deliberate rejection of the locally entrenched opposition between (sexual) minority discourses and discourses of patriotism is highlighted here. The tension between conceptualization of sexuality in relation to citizenship, which has arguably grown within the past decade and after one yet again cancelled Pride parade in 2009Footnote 12 (Blagojević Reference Blagojević, Kulpa and Mizielinska2016), has given homosexuality a central symbolic place in Serbian discourses of patriotism, constructing it as significant opposition not only to family values, but to the nation itself. Nationalist groups cast LGBTQ people as antinational subjects, and, as shown in, for example, Canakis's (Reference Canakis2018) detailed investigation of extreme nationalist graffiti in Belgrade, a sexualized version of the ‘foreign mercenary’. The ads confirm the salience of interrelations of nationalism, sexuality, and masculinity that has formed a local indexical order (cf. Baker & Levon Reference Baker and Levon2016); still, they demonstrate how these are reworked in specific ways in minority groups, often placing the appropriate gay identity closer to a masculine ideal that goes hand in hand with the national ideal.

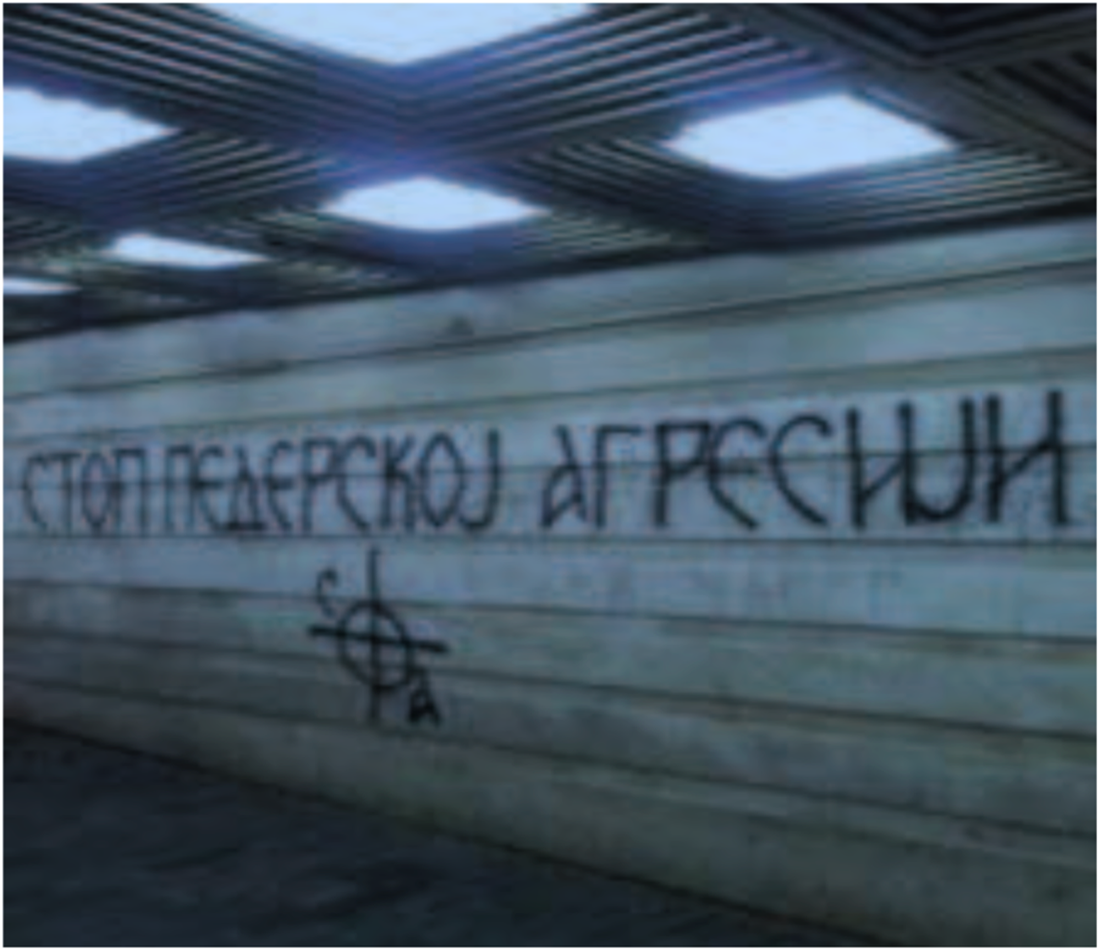

In this vein, there are more striking ads that even seem to adopt actual quotes of anti-LGBT slogans, which spread over the previous years in right-wing nationalist circles and hate grafitti.

(15) Thor (18, PlanetRomeo)

Nefem, lepi u faci, ispod 20 god, bez golih slika, normalni. STOP PEDERSKOJ AGRESIJI.

‘Nefem, handsome face, under 20, no naked pics, normal. STOP TO FAGGOT AGGRESSION.’

The capitalised sentence echoes the well-known threatening writings found in the graffiti landscape of the capital Belgrade in particular, reproduced around Pride parade dates (see Figure 1 below). The conciseness of the ad leaves the option that the statement may be playful or ironic, though coupled with the previous reference to naked pictures, noneffeminateness and normality this seems less likely. The Stop format (found in some other slogan-like statements of pederi stop ‘fags stop’) allows seamless integration of content, essentially reproducing an opposition between the ‘normal nonfem guys’ and the ‘faggot aggression’ of those who do not fit the desired description. The broader framing of gay visibility and activism as aggression, salient in the local anti-LGBTQ discourses, is taken up with a shifted meaning in the in-group context, that of overly-sexual and pushy ‘gay gays’; the attack on social values and national space refracts the attack on personal values and intimate space, while the level of playfulness and self-irony remains perhaps deliberately open.

Figure 1. Stop faggot aggression, underpass in Belgrade (from Canakis Reference Canakis2018:239).

Overall, again, analysis of lexical collocates and broader context confirms that the upholding of stereotypical masculinity and distancing from stereotypical ‘gayness’ works in recursive intersection with broader social expectations and ideologies. It is important to note that such textual representations of identity may still clash with other performances of identity (the repudiated fem men are by no means as invisible in the Serbian LGBTQ clubbing or popular culture), while the representations of desire may just as well not match the experiences of desire. The findings highlight how the two key concepts in language and sexuality scholarship, namely identity (cf. Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2004) and desire (cf. Cameron & Kulick Reference Cameron and Kulick2003), overlap in complex ways, so that rather than privileging one or the other it is more gainful to adopt an approach that acknowledges the patterns of normativity and normalisation central to identity presentation in marginalised groups, and underlying the intersections of desire, identity, ideology, and power (cf. Milani Reference Milani and Preece2016).

Finally, the salience of the normalisation mechanism is confirmed most of all in the standout pattern of normalan—the major collocate of the keywords under scrutiny, and the highest positioning adjective in the keyword list.

IN SEARCH OF ‘NORMAL’ GUYS

The major overt signal of normalization, the adjective normalan ‘normal’, again involves associations with appropriate masculinity, collocating with nefem(iniziran), momak, muškarac, and in contrasts and concessions with gej and fem(iniziran).

(16) QQ (31, Grindr)

Ako postoje normalni nefem tipovi, sa muskim mozgom i razmisljanjem neka se jave .. ostali STOP!

‘If there are any normal nonfem guys, with a male brain and behaviour, contact me .. others STOP!’

(17) Ticki (26, GaySerbia)

Bavim se sportom, završio sam fakultet, ti trebaš isto, ili bar da studiraš, da umeš da sastaviš rečenicu, potrefiš padež, argumentuješ bez svađe, svađaš se bez drame, you get it…Normalna osoba iako gej, da to ne kriješ, i da si spreman za pravu vezu

‘I do sports, I've graduated from university, you should have the same, or at least be studying, you should be capable of composing a sentence, getting the case form right, argumenting without a fight, fighting without drama, you get it [English]… A normal person though gay, not hiding it, and ready for a real relationship’

(18) wwx (28, GaySerbia)

NORMALAN MOMAK STR8 ZIVOTA PONASANJA RADIM ZIVIM SAM VOZIKAM SE PO EVROPI UZIVAM SAMO MI FALI DOBAR FRAJER ZA UZIVANJE

‘A NORMAL GUY OF STR8 LIFE AND BEHAVIOUR I WORK LIVE ALONE RIDE AROUND EUROPE ENJOY I JUST NEED A GOOD DUDE TO ENJOY’

The examples can be easily interpreted based on the patterns already seen, but they also allow us to sum up some broader tendencies that I find to be central here. While the texts surely uphold sexual and gender normativity and echo heteronormative pathologizing discourses of abnormality, another ideological process central to recursive normalisation is observable. It is a reworking of neoliberal sexual politics of equal rights and public visibility—an important aspect of Serbian LGBTQ activism with tangible successes, but one that positions itself in assimilation to entrenched ideals of good citizenship. In this normalizing logic, to use Seidman's (Reference Seidman1998) term, ‘gayness’ can be acceptable provided that every other aspect of the gay self demonstrates what would be considered ‘normal’ gender, sexual, familial, work, and national practices—in the examples above, ‘normal male thinking’, graduating from university, working, having a ‘proper relationship’. In the communities under study, positive imagination of the ‘normal’ combines values both local and global (e.g. the comments on using the case system properly in (13) reflect local language ideologies that position certain Serbian dialects as inferior (Petrović Reference Petrović2015); ‘riding around Europe’ in (18), evokes global mobility practices still inaccessible to the majority of young people in the country); still, such imagination is generally seated within other established systemic hierarchies beyond gender/sexuality. Crucially, in this frame, sexual behaviour becomes merely an additional aspect of the gay self that otherwise reproduces all aspects of the ideal male citizen; in the process, a segment of different gay selves that do not conform to this ideal—in profile writers’ own disappointed words, a huge number of/an army of/a sea of gay men—remain outside of this acceptable group.

As seen in many of the above examples, the masculine, normal guys and normal gays become a point for distancing from this group of non-normal others in ways that are direct and adversarial. The antithesis of the normal man here is a peder ‘fag’ but also sometimes a woman (ako ste tražili devojku, na pravom ste mestu ‘if you were looking for a girlfriend you're in the right place’; da hoću vas ženice za shopping i zvocanje ne bi bio ovde ‘if I wanted you little women for shopping and nagging I wouldn't be here’). On the whole, despite the presence of a range of gay identities (the men-seeking-men segment includes persons self-identified as bisexual, nonbinary, transmasculine), the profile descriptions of the self and desired other are dominated by a normalizing logic of ‘proper men’ that excludes the more radical aspects of digital communities and LGBTQ movements.

On a final note, however, this dominant pattern is not without challenges.

(20) LLL (20, PlanetRomeo)

U bg samo radnim danima, normalan momak da, pri tom nisam apolon, mozda sam i fem, svim modernim urbanim machoima bih preporucio da procitaju neku knjigu, neku realnu queer teoriju na primer

‘In bg only on work days, a normal guy yes, but not an apolon, maybe even fem, to all modern urban machos, I'd suggest you read a book, some real queer theory for example’

(21) Kicky (19, PlanetRomeo)

Piši ako imaš šta da kažeš….. jer ja gubim strpljenja muka mi je od istih profila i fem nefem batica……ja od života i od sexa hoću šta hoću, pogledajte sebe prvo, zapitajte se ko ste da meni govorite da li sam dobar peder loš peder

‘Write if you have something to say….. since I am losing patience I am sick of the same profiles and fem nonfem dudes….. From life and sex I want what I want, look at yourselves first, ask yourselves who you are to tell me if I am a good fag bad fag’

The first text adopts the concept of normality, but overtly challenges the divisions based on appearance and masculinity. The critical tone also evokes the locally relevant distinction of the ‘modern urban’ and the ‘backward rural’ (the author stresses he does not live solely in the city of bg, Belgrade) by addressing the persona of an urban macho who is in fact not educated, and would benefit from reading, especially from reading ‘some real queer theory’—an allusion that adds authority and authenticity to the self-presentation. While not taking this position of knowledge, Kicky takes a more explicit, personal stance that precisely reflects the queer-theoretical challenges to essential identity categories and policing of sexual behaviour. Perhaps accidentally, both examples come from the later period in the corpus and from users not over twenty years of age. What they show is how theory can leak into desire-laden communicative practices and be remoulded there, and that the ways minority groups themselves theorise their relations merits more attention. More importantly, however, the analysis overall suggests some potential pitfalls in theory and political movements focused on social assimilation as a way of fostering collective identity. This is further reflected on in the Discussion.

DATING SITES AND LBRTD APPS

At the end, a brief comparison between the two dating modalities is needed. Overall, qualitative analysis shows great similarities in representations and workings of recursive normalisation in the sites and Grindr app profiles. These are confirmed through corpus techniques, which reveal similarities in keywords.

Despite great comparability in linguistic patterns, differences between the profiles on the two dating platforms need to be noted. First of all, LBGRT profile descriptions are typically more concise (Batiste Reference Batiste2013), which was confirmed both through the analysis and data collection—satisfying my criterion in data collection was harder for Grindr, since a large portion of profiles contain no text, but only a photo/stats. Relatedly, while very short, three-to-four-word texts like Normalni, nefem, svoja kola ‘Normal, nonfem, own car’ might come across as odd in personal ad pages, they are very common as brief notes that accompany the Grindr picture—and even in this short format include aspects of othering and normalisation. Additionally, while departures from the sequential structure of ‘ADVERTISER seeks TARGET…’ are common in general, website profiles demonstrate a looser structure than Grindr, frequently entailing very long descriptions of the unwanted or the dissatisfaction with ad-based communication, whereas Grindr is more pragmatically focused on sexual encounters. Still, the distinction is not as sharp, and most types of text could be seen both in ad sites and Grindr; many users explicitly state having profiles on both, and writing and browsing may lead to some convergence of patterns.

Finally, as illustrated in (22), some users comment on using the Grindr app and browser-based ads for different purposes, which include safety concerns.

(22) KP (24, PlanetRomeo)

Ovde [PlanetRomeo] sam prešao kad su mi se smučili hoteri na Grindru, ali sve isto sr***.

Makar ne brinem da će me neko snimiti preko ramena

‘I moved here [PlanetRomeo] when I got sick of the hotters on Grindr, but same sh**. At least I don't have to worry someone will catch me over my shoulder.’

Being caught using the app ‘over the shoulder’ is an explicit reference to the dangers gay men still face in their physical surroundings. It suggests a distinction between web-based ads being used in more private, home settings, and Grindr whose main point is in its geolocation possibilities outside the home (though the opposite is just as possible in practice). In any case, such comments suggest that the anticipated migration to mobile-based apps may take a different pattern in different sociocultural contexts.

DISCUSSION: MARGINALIZATION, ASSIMILATION, AND RECURSIVE NORMALISATION

Corpus linguistic techniques provided a productive lens for examining the social discourses of the dating sites, confirming their great potential as a basis for studying ideology. A point of note is the relevance of grammatical collocates—typically discarded in analyses as less telling—that revealed some important patterns in the corpus concerning distancing and rejection. Overall, the analysis has shown that Serbian gay men utilize web-based dating sites and apps in an adversarial and almost ritualistic distancing from ‘effeminate’ gay men, evidenced through patterns of negation, concession, and evaluative concept association. However, their effects involve not only othering of undesired masculinities, but a blurring of boundaries and more complex recursive intersections of values.

Without a doubt, the post content observed ties in with the conflicts of sexual presentation and traditional values in Serbia. Many of the posts explicitly refer to the local setting, and echo the tensions between ‘modern’ gay masculinites and traditional local norms, where rejecting the nonmasculine goes to the point of co-opting the heterosexist slogans of the local far-right. Before we situate this local context within the patterns observed, it is important to stress that such focus on traditional masculinity is by no means solely Serbian—nor can any LGBTQ subculture today be understood in isolation from global trends. Many users have profiles on international sites as well, include translations into English, reference their experiences in other locales, textually mix languages or cite anglophone pop culture references.Footnote 13 Queer voices in popular commentary from other parts of the world have problematized similar tendencies (consider the popular Douchbags of Grindr, or the NO FATS NO FEMS memes, dedicated to humorous criticism of gay culture exclusions; cf. Shield Reference Shield2018). As discussed below, the tensions in profile presentations are centrally about situating gayness, with its history of violent othering in the country, within a frame that still fits the ideal of a good Serbian citizen—a construct clearly shown to mix entrenched values both local and global-systemic. What in any case emerges from the profile presentation is that queer digital networks do not merely construct friendly spaces for expressing non-normative desire, but that they largely perpetuate many of the (locally and globally current) normative restraints through intersectional associations.

For one thing, the economy of sex and obsession with media-driven aesthetics, which appear to be commonly acknowledged in queer culture (micro)blogging and social websites, epitomize a very masculine ideal; any falling short of this hetero-looking masculinity is often stigmatized among gay community members, as a kind of ‘internal’ stigmatization. Still, the present findings confirm the inadequacy of the popular concept of ‘internalised homophobia’ when discussing what is apparently a more multifaceted and fluid process. The dating profiles do not simply suggest repudiation of everything ‘homo’—elements associated with gay culture, such as the celebration of casual sex and the celebration of the male body (not part of mainstream hetero masculinities), are retained. Moreover, as mentioned, the undesirable gay identities are always locally shaped and not simply ‘homo’ (e.g. the desirability of ‘white’ masculinity, evident in the ‘no blacks, no asians’ blurbs, bears no relevance in the Serbian context, while other locally specific identities, such as the modern city man versus the turbo-folk-pop culture rural type, do matter). The ‘phobia’ part appears equally problematic, working to almost pathologize behaviours without locating them within larger systems of power. The epithet ‘internalized’ homophobia, finally, merely suggests acquired and static mainstream norms. The high engagement with the profile pages analysed here, along with the authors’ elaborate comments on their social reality, all highlight the great agency of gay men as they co-construct the meaning of ‘desirable’ or ‘appropriate’ gay masculinity.

This is where the concept of recursive normalisation has provided an adequate apparatus to account for the dynamic construction of the desirable. In Irvine & Gal's (Reference Irvine and Gal2000) terms, the wider social opposition between negatively conceptualized feminine (and gay) characteristics and positively conceptualized masculine (and heterosexual) traits is recursively projected inwards. By adopting such oppositions and constructing a subgroup of aberrantly gendered ‘others’, the post writers are able to indirectly index the normativity, and, in the process, normalise, their own gay selves. Sexual behaviour is constructed as a minor aspect of the ‘normal male’, who in all other aspects conforms to the desired ‘normal’ life, in Serbia, in the global system and the current political economy. The normalising logic, as a major feature of contemporary discourses on sexuality (cf. L. Jones Reference Jones2016, Reference Jones2018), from public LGBTQ activisms to the intimate imaginaries of dating sites, is recursively refracted into the Serbian gay communities, intersecting with the local values that range from patriotism and familial responsibility to correct language use. Importantly, as the data have shown, such recursion of systemic hierarchies invariably results in recursive marginalisation of the ‘sea of’ men who do not fit the imagined norm.

However, the process is also seen to work in crossways (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019), multiple, and overlapping directions. The dating context analysed shows that recursive normalisation allows distancing from socially marginalized gender and sexual identities and positioning one's own identity as closer to the traditional model of masculinity. In this process, the writers do largely perpetuate the discourses of hegemonic masculinity. At the same time, however, they exhibit resistance to existing social representations, both by creating symbolic links to an alternative gay manhood and by constructing gay male sexuality as not necessarily outside of the realm of hegemonic masculinity. Such positioning thus simultaneously works to preclude stereotypicalization and erasure (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine and Gal2000), in which identities inconsistent with the dominant representations (e.g. masculine gay men) tend to be rendered invisible by ideology. Finally, the ad writers are shown to mould their representations of desire according to what is socially valued, projecting the imagination of ‘good’ self and partner identities, but there may well be a large discrepancy between such representations and the actual experience of desire (in the interviews I have conducted, no gay men from Serbia thought it was hard for effeminate men to find romantic partners). This complexity of relations, their recursive nature, along with the intersecting of desire and identity, need more nuanced attention from scholars, where emic, in-group theorizing in communicative practice is invaluable.

Importantly, the dynamics of recursive normalisation and recursive marginalisation warn of the pitfalls of theory and social movements focused on social assimilation. As Seidman (Reference Seidman1998) more broadly describes normalization as spreading globally from American individualist liberalism (cf. Alexander & Smith Reference Alexander and Smith1993), it always merely demands acceptance and recognition of a minority status, not a challenge to (hetero)normativity. At the same time, it reproduces the dominant order of gender, of intimate, economic, and national practices. In LGBTQ movements, such focus on acceptance—or ‘tolerance’, to use a common term in Serbian equal rights discourses—is bound to neutralize the more critical or radical perspectives that might call existing hierarchies into question. The hegemony of those who ‘tolerate’ is unquestioned. In this sense, the ritualistic rejection of effeminacy in the dating profiles, though specifically adversarial and imbricated in local ideologies, is in many ways a reflex of the social assimilation discourses. Non-normative sexual identities are made acceptable as long as they are in all other aspects the mirror image of the ideal heterosexual citizen, preferably with sexual identity invisible and not held central to one's perception of self. From this point further, it is the queer theoretical and political voices that can open more emancipatory space, mainly in exposing the disciplinary, exclusionary, and marginalising upshots of ‘tolerance’, strongly confirmed in the present findings on recursive normalisation. Future research needs to both understand and deconstruct the normalizing divisions between ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ sexualities that have produced the imagination of deviant sexual selves in the first place.

Finally, recursive marginalization, as a product of (recursive) normalisation, is by no means limited to the construction of sexual and gender identities. It highlights the common and underresearched processes by which core members of any socially marginalized group can also be positioned as marginal within that group, by virtue of being viewed as the most typical representatives of a socially delegitimized identity. In one of my datasets of teenage personal ads, a self-identified gay Roma userFootnote 14 describes himself as “serious, not a typical Roma, clean, neat, normal”—openly echoing the social perceptions of the ‘typical Roma’ as not clean, neat, and the opposite of normal, though he actually admits in the other part of the post that he would like to meet other gay Roma men. This is another case where broader social oppositions are projected inward into intergroup oppositions, with distancing from the typical representatives of socially stigmatized identities, which may or may not be in line with real-life social and sexual preferences. To give just one broader example from my English language research (Bogetić Reference Bogetić2019), there is uptalk, a supposedly female speech pattern increasingly ridiculed by US women themselves as indexical of some imagined ‘typically girly’ insecurity and powerlessness.

Altogether, what is clear from the described patterns is that we need more nuanced insights into marginalized groups’ own recursively built ideologies and power relations, rather than romanticizing the agency of their social networks and digital communities. A further queer linguistic focus on normativity and normalisation is much needed for a socially relevant, counter-hegemonic language and sexuality scholarship. Understanding the mechanisms of recursive marginalization within larger structures of power is not only a needed thread of research, but also a prerequisite to any attempts at effecting social change.