Abstract

This paper investigates case and agreement patterns in Iranian languages, mainly focusing on Zazaki and Kurdish varieties. Empirically, the paper discusses the typologically rare double-oblique pattern, along with a novel way of splitting the oblique. On the basis of the syntactic behavior of oblique-bearing arguments, the paper argues that the term ‘oblique’ corresponds to distinct cases, ranging from structural accusative case to nonstructural dative case and ergative case. Oblique number agreement is case-sensitive, targeting only ergative-oblique out of the oblique cases. In order to capture the facts, I adopt a Multiple Agree account (Hiraiwa 2005), in which partial number agreement is a process that takes place in the morphology via Impoverishment, and not in the syntax proper.

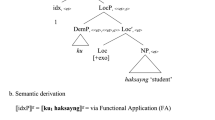

The study proposes to capture the case patterns in Iranian languages along the lines of Svenonius (2006), in which arguments bearing nonstructural case get their licensing from a combination of two heads (cf. Chomsky 1993), one of which is Stem, the locus of split-ergativity in Iranian. A chain is established between Stem and v, which yields the nonstructural case on internal arguments, whereas the ergative case on external arguments is the result of the chain between Stem and Voice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is identical to the standard/literary Kurdish variety described in Thackston (2006) in most respects, including the alignment system.

Following Dixon (1994), S stands for the subject of an intransitive verb, A for the subject of a transitive verb and O for the object in a transitive verb.

This pattern is also found in the dialect spoken around Diyarbakır, studied by Dorleijn (1996:62, 118), in some languages of the Tatic group, spoken further to the East, around the Caspian Sea (e.g. Vafsi and Kafteji, Stilo 2009:706, 709). Among the other branches of Iranian, Stilo (2009) also mentions West Balochi and Roshani, Kaufman (2016, 2017) Wakhi, and Windfuhr (2009:34) adds Semnani and Yaghnobi. Payne (1980) discusses the double-oblique pattern in Pamir and gives a diachronic account of its development.

In fact, Öpengin and Anuk (2015, 2016) are the first researchers to draw a short descriptive sketch of the case and agreement patterns in the Zazaki variety, which they also call Mutki Zazaki. Although they alter their descriptive generalizations in their latter study, their descriptions still show a few discrepancies from our intuitions. As such, I choose to independently describe Mutki Zazaki and make reference to Öpengin and Anuk (2015, 2016) in cases where data converge. It is possible that the variation in descriptions is a result of the exact locations, i.e. villages, each variety is spoken in.

This is not a common type of syncretism, yet it should be noted that Iranian languages exhibit a wide range of uncommon syncretisms. For instance, in Anbarani dialect of Taleshi, the DIR versus OBL case distinction is retained only in 1sg (Paul 2011:81), and other persons are syncretic. Kaufman (2016:5) reports another uncommon syncretism in Wakhi, where 3sg and 1pl are syncretic while other pronouns have distinct forms.

The personal pronouns in AK do not exhibit syncretism within or across DIR and OBL (Atlamaz 2012:73). MK also has no syncretism between DIR and OBL forms of the personal pronouns; however, within the DIR paradigm 3sg and 3pl are syncretic, and have the exponence ‘ew.’ Moreover, both AK and MK mark gender only in the third singular in the OBL (Gündoğdu 2011:51).

Another possibility is that topichood might play a role. Thanks to Alison Biggs (p.c.) for bringing this to my attention. Topichood does not appear to be a factor: Both sentences çı bı? ‘what happened?’ and Kemal çı ke? ‘what did Kemal do?’ can be answered with either option.

I should also note that in MZ even in a context where the subject lacks volitionality/responsibility (e.g. having to run down a hill due to its steepness), the subject of an unergative verb may only get OBL, and not DIR.

Although ‘optionality’ certainly requires an in-depth investigation in each case, it might be more prevalent than it is usually considered. For instance, Lithuanian shows a parallel optionality to MZ unaccusatives, in the context of passivization without any correlates. F. Sigurðsson et al. (2018) show that verbs like help in Lithuanian allow their dative object either to change to the nominative or retain its case in passives. The nominative theme agrees with the participle, while the dative does not.

See also Haig (2017) on the absence of DOM in Kurdish and Zazaki despite its presence in some other Iranian languages.

I thank a reviewer for pointing out that OBL is already not treated monolithically in Iranian linguistics, and it is usually suggested that OBL O in the present stem is taken as ACC, and OBL A in the past stem is regarded as ERG (cf. Payne 1980; Dorleijn 1996; Stilo 2009; Haig 1998, 2008; Atlamaz 2012; Baker and Atlamaz 2014; Atlamaz and Baker 2016, 2018; Karimi 2013, 2015; Kaufman 2017; but see Bobaljik (2008:fn. 3) where no distinction among oblique cases is drawn for some other languages). Acknowledging this classification, the categorization here is based more on syntactic behavior of arguments bearing the OBL case, therefore still differs from the previous literature in which the syntactic aspect is not the prominent factor.

A reviewer asks whether a ‘high passive,’ in which you have an active clause case license the object, then passivize on top of that, could provide an alternative explanation for the case preservation property of passive. This suggestion resembles the grammatical object passive or new passive (e.g. Maling and Sigurjónsdóttir 2002; Legate 2014b), in which the agent is partially projected. In this construction although the verb bears passive morphology, the theme remains as the grammatical object (with accusative case). Although it is an interesting suggestion and it could explain the fact that the verb shows default agreement (as in the Icelandic new passive), it does not explain other facts. One of the hallmarks of the grammatical object passive is that raising the thematic object to the grammatical subject position is ungrammatical, in contrast with the canonical passive. However, we see that the theme shows the behavior of a grammatical subject in MZ, in that it can bind the subject-oriented reflexive (23)–(24). The same argument extends to another potential interpretation of the reviewer’s ‘high passive’ as impersonal passive.

Given Haig’s (2008) remarks on quirky patterns in Iranian languages, we can treat this pattern as an unstable property, likely to change via levelling to the whole paradigm over time.

Still, if we concentrate on the synchronic picture, 2sg person behaves like the persons in Muş Kurdish, in that the OBL O bears structural case, and the S argument bears DIR. I leave the significant issue it raises for syntactic versus morphological ergativity or person-based ergativity noted by a reviewer for future research (cf. Legate 2014a; Deal 2016; Polinsky 2017).

A reviewer suggests that the two passive structures are incomparable for case purposes since MZ has synthetic passive, whereas MK has periphrastic passive. However, their discussion focuses on AK, which does not allow syntactic passivization and thus does not play a role in this discussion. They say that AK, which on the surface has the same form as MK, i.e. the main verb realized as a participle, and a light verb bears the agreement, does not allow by-phrases. The claim here is not that all the dialects that exhibit similar surface realizations would need to behave identically. In fact, I suggest the opposite, in that two morphologically different systems may have the same or very similar syntactic systems for a certain operation such as passive. It is clearly a non-trivial question why, of the two dialects that look alike, only one (i.e. MK) allows syntactic passivization and the other one (i.e. AK) does not. However, I make no claim with respect to the status of the OBL argument in AK. Since the criteria for the nature of OBL arguments are based on their syntactic behaviors, I focus on languages in which these are applicable, such as MZ and MK.

Regarding the synthetic vs analytic passives, it is possible to give examples of several, (closely) related Iranian languages/dialects, which differ in their choice of the passivization strategy without it necessarily having a syntactic effect. For instance, Sorani (Kareem 2016) and Hawrami (Holmberg and Odden 2004) have synthetic passives, unlike MK. Among varieties of Zazaki, the Siverek dialect also has synthetic passives (Todd 2002), whereas the closely-related dialect studied by Csirmaz and Ceplová (2004), Kenstowicz (2004) has periphrastic passives. Despite the surface difference, they all behave like syntactic passives. From a crosslinguistic perspective, it is even possible to see the two strategies of passives within the same language, e.g. Latin, while generally a synthetic passive language, the periphrastic passive is employed for perfect tenses without necessarily corresponding to a deep structural difference that affects the syntax of the passive (Embick 2000) (Thanks to David Embick (p.c.) for the discussion of this point).

Some speakers use the form biNP ‘with NP’ for by-phrases. I should note that Gündoğdu (2011) also suggests that O bears ACC case; here I provide several arguments to substantiate that claim.

PRO-control tests for subjecthood could not be applied to the Zazaki data, as non-finite complementation is not an option in Zazaki. In the contexts where languages use non-finite complement clauses in which PRO is licensed, Zazaki (and Kurdish) resorts to a finite clause with subjunctive mood, and does not have a PRO subject.

In Hawrami, a case-marked cognate object indicates progressive aspect (Holmberg and Odden 2004).

A reviewer suggests that (47) is ungrammatical because reflexive binding is not possible for their consultant. I would like to direct the attention of the reviewer to fn. 42, in which I discuss the existence of two groups of speakers for AK for this construction (as well as in MZ): one group of speakers, call it Group A, does not allow reflexive binding; yet the other group of speakers, Group B, find the reflexive binding possible.

Unlike the dyadic experiencer construction, which is discussed in Sect. 3.3.3, the experiencer construction here contains a sole argument regardless of this variation with respect to reflexive binding. Therefore, the sole argument functions as a grammatical subject for some, but not others.

Note that there is also some variation at the morpho-phonological level, which I again illustrate in the example (47) and those in fn. 42. For instance, the past copula in this example is realized as bû for Group B speakers, whereas it is -u for Group A (although Group A speakers also have bû in other examples, e.g. (54b) or relevant examples from Atlamaz 2012; Baker and Atlamaz 2014). Similarly, the adjectival predicate ‘cold’ is pronounced as sar by Group B, while as sor by Group A. One could treat these variations as reflexes of two separate dialects, or just surface-level variations of the same dialect due to the colloquial nature of these languages. According to the latter view, which I have chosen, we are dealing with the same dialect that has two groups of speakers for reflexive binding, but does not attribute much importance to the variation in phonological differences. Note that not much would hinge on the choice of either option; treating them as two separate dialects would just mean that the discussion here focuses on the grammar of Group B speakers. Finally, the reviewer’s example places the phrase containing the reflexive before the predicate. Group B speakers expressed no such preference.

Haig (2008:305–310) describes this class as verbs with verbs of sensory perception, desire, and obligation.

A reviewer raises some questions concerning the status of (50) in AK. Baker and Atlamaz (2014:10) say: “...AK does not (as far as we know) have the relevant clause type, but Sorani does ...” However, the reviewer suggests that this construction is available in AK. Clearly, more investigation is needed here, but since our focus is on the significance of the MZ pattern, I leave this for future work.

Note that this conclusion is also compatible with the well-established fact that transitive clauses in ergative languages have subjects in ergative case, but intransitive clauses do not (Baker 2015). I also conclude the oblique on intransitives is distinct from the oblique on transitive subjects.

It is also possible to implement a case decomposition approach for the case representation, as such individual cases like “nominative,” “dative,” etc. are not the names of individual features in the grammar. Rather, these names stand proxy for different combinations of features; see Halle and Vaux (1998) and Calabrese (2008) for two such approaches. On Calabrese’s (2008) system [source] differentiates ERG from other cases, with ERG being [+source], and other cases [−source].

A reviewer suggests that given that OBL is syncretic in a single language for more than one case, it is desirable to explore a featural decomposition to spot the feature they share. I agree with the reviewer that a featural decomposition is natural, and in fact possible. For instance, in Calabrese’s (2008), the feature [+motion] distinguishes ERG, DAT and ACC from NOM. Acknowledging a decomposition approach, I still preserve the traditional labels for exposition, since they suffice to explain the facts.

This generalization may be relaxed to capture the optionality of this non-canonical agreement. One option is to say that 3rd person is morphosyntactically ambiguous between having the person feature encoded and lacking the person features. Atlamaz and Baker (2018) speculate that this could be an instance of speakers controlling more than one dialect/style of Kurmanji (e.g. diglossia between AK and SK) or a grammatical effect. Their grammatical effect follows the implementation of Multiple Agree by Marušič et al. (2015) in which agreement is a two-step process: Agree-Link, happening in the syntax and Agree-Copy which happens at PF. The relative ordering of Agree-Copy with respect to other PF operations could be what is leading to this variation. At this point, this aspect also remains at the speculative level.

It should be noted that Atlamaz and Baker (2018) also make use of the feature-geometry to explain the contrast between local and non-local persons. They suggest that when number (plural) fuses with the oblique case, plural agreement can show up on the verb; when number does not fuse with the oblique case, there is no agreement between an oblique subject and a verb. With local persons, the participant node between K(ase) and number blocks the fusion. Thus, their nominals consist of the Kase > Participant > Number hierarchy. Thus a slight change in the tree representations here, in which Kase dominates person and number Atlamaz and Baker (2018:20), and allowing the probe to look further down past Kase would mean that T would look at case feature (ERG) and keep looking further down. When it finds person feature next, the search fails.

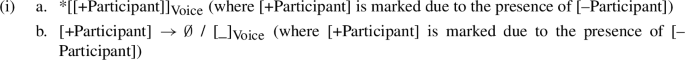

Another option is to capture this systematic asymmetry via Impoverishment (credits to David Embick and Jonathan Bobaljik (p.c.) for independently bringing this up). The Impoverishment would delete the person feature of the DP1 (indicated via the subscript 1) in the context of ERG once the features are transferred to T. This is illustrated in (i).

-

(i)

[αperson]1

→

∅

/[__ erg]

This Impoverishment would be followed by the Impoverishment rules in (60). As far as I can tell, either approach makes the correct prediction empirically. Both options capture the fact that local pronouns and other nominals differ in their ability to trigger number agreement, in that only the latter may do so. I opt for the feature-geometry.

-

(i)

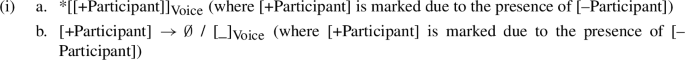

A similar line of analysis (and its variations) that incorporates Multiple Agree with Impoverishment has in fact been proposed to account for Algonquian theme signs (Oxford 2014, 2017; Despić and Hamilton 2018). For instance, Despić and Hamilton (2018) suggest that in Algonquian languages, Voice has access to the ϕ-features of multiple arguments via different methods: in the syntax, the object is probed downwards via Agree, and subject ϕ-features are accessed via Merge. Post-syntactically, although only the features of the object are spelled out, the features of the subject can affect the features of the object. Implementing a system of markedness conditions, they propose that the marked feature of the object, e.g. [+Participant], is deleted postsyntactically via Impoverishment prior to vocabulary insertion in the context of [–Participant] feature of the subject. This is illustrated in (i).

-

(i)

Although the contextual markedness does not straightforwardly extend to the pattern in Iranian languages, what is common to both this approach and that of Despić and Hamilton (2018) is that the postsyntactic deletion of certain feature(s) in the context of another feature.

-

(i)

For instance, VIs for the auxiliary ‘be,’ which usually has different exponence, are left out. Some other remarks are in order regarding VIs: it is possible to do a more worked-out phonology for the VIs or reduce them, but since it is not the main concern here, I leave them as is. I also make the assumption that the inherent features in VIs carry more weight in terms of specification than the contextual information.

The case/phi-features of ERG and NOM-bearing arguments are dissociated (in the sense of Embick 1997; Embick and Noyer 2001) into agreement morphemes. However, the case/phi-features of ACC/DAT-bearing arguments remain on T, thus are never realized. That’s why, there is no VI for the latter arguments. This accords with suggestions of two reviewers.

Given that the same configuration is strongly disallowed in MZ, I lean towards interpreting the MK sentence in (68c) as another indication that the features of the internal argument are visible. Despite the variation in (68c), (68b) is invariably ungrammatical with the plural agreement on the verb.

The structures are not exactly identical to the ones in Atlamaz and Baker (2018:e.g. (51)) in terms of how subject and object are represented. They represent the nominal as hierarchically organized ϕ-features. I choose to illustrate them simply as NPs, since it makes no difference for this part of the discussion.

The failure of the expected correlations between stem and clausal tense is attested in other Iranian languages as well. For instance, the Awroman dialect of Gorani has a tense, which is based on the present stem, and referred to by MacKenzie (1966, cited in Haig 2008) as the Imperfect. Crucially, the Awroman Imperfect has past-tense reference despite the present stem. Similarly, the Badīn dialect of Northern Kurdish has a past irrealis (‘I would have done X’) based on the suffix da- plus the present stem of the verb. Again, it expresses a past-time reference. A very similar development is noted in Talyshi, where an imperfect tense with past tense reference is found, but based on the present stem of the verb (Stilo 2009). These instances further support the view that “in Iranian it is not primarily some semantic notion of ‘pastness’ or ‘perfectivity’ that is crucial to triggering ergativity, but the historical link between certain verb forms, and a particular alignment type” as stated by Haig (2008:9).

Thus unsurprisingly in Iranian linguistics, even for the languages like Wakhi, some dialects of which have split-ergative pattern (upper dialect of Wakhan) as well as other dialects with only nominative-accusative alignment (lower dialect of Wakhan), the discussion is usually about stem, and not tense (or aspect) (e.g. Bashir 2009 and other articles in Windfuhr 2009).

The authors use the term ‘T’ in their paper in its traditional sense, as referring to the T node, but their ‘T’ in fact corresponds to the morpheme ‘Stem.’ Given the examples in (81)–(85), I take it that this morpheme is introduced lower in the clause, whereas the copula is introduced in T.

Kalin and Atlamaz (2018) note that unlike causative morphology, V-Stem allomorphy is not blocked by an overt exponent for Asp in Kurdish. This is indeed expected given that v is immediately dominated and linearly adjacent to Stem, whereas Asp is higher in the structure, thus does not interact for allomorphic purposes.

It is reminiscent of AgrP of Chomsky (1993) in terms of requiring more than one head for case assignment.

A reviewer suggests that Svenonius’s (2006) concept of chain and its implementation here makes it structural rather than nonstructural. This is because it is determined in the syntax by structural relations/configuration among multiple heads, unlike the classic Inherent case view, which essentially boils down to assignment of inherent case by a head due to its particular features. As the reviewer notes, a view I also share, Inherent case assignment actually requires a specific configuration of Transitivity (for ERG) and ‘pastness’ (which is a property of Stem, not of T). Therefore, the classic view faces problems, a view I do acknowledge. That is the motivation behind the chain operation. However, I refrain from calling the necessary configuration among multiple heads ‘structural’ and would like to reserve the term ‘structural’ to its standard definition, as in e.g. Chomsky (1981, 1986), Woolford (2006). That one of the heads is the head that assigns the θ-role to the ERG DP is also relevant, since on-structural case was traditionally the case assigned along with a θ-role. As such, structural refers to instances where case is lost under A-movement as opposed to nonstructural where case is preserved under A-movement.

An example of unergative predicates is shown in (i). Note the presence of a clitic as well.

-

(i)

Related to fn. 31 and the current discussion, it should be noted that literature on dialects of Wakhi reports different case properties for different dialects. For instance, Bashir (1986) notes that past intransitive subjects may get both OBL and DIR, and this correlates with volitionality or topichood. Payne (1980) notes the same pattern, but says that the two coexist in free variation in the past stem. Kaufman (2016, 2017) reports the existence of only OBL in the same contexts for the dialect he investigates. Thanks to Daniel Kaufman (p.c.) for the elicitation of Wakhi data from Husniya Khujamyorova, and the discussion.

-

(i)

Nie (2017) suggests that ergative case may be assigned by Voice to its DP specifier only if the vP sister of Voice has the correct set of nominal licensing features: [D, ϕ], where D is the nominal features, and ϕ is the agreement features. The basic idea behind Nie’s (2017) view is similar to that of Deal (2010), in that ergative requires Voice to access information lower in the tree. See also Legate (2017) who suggests that what counts for “transitivity” is different in different languages.

However, it should be noted that although it is commonly assumed that ERG is restricted to past tense or perfective aspect, the experiencer subjects discussed in Sect. 3.3.3 demonstrates that this is not exceptionless. We see that ERG applies not only to initiator, but also experiencer, which is another external argument role.

Again languages/dialects (even clause types) might differ in their level of “OBL spreading.” For instance, Wakhi intransitives exhibit a different behavior depending on the dialect. The discussion of the precise factors, particularly the language external ones, which condition this variation, however, would take us too far afield. Likewise, experiencers are OBL-DIR, rather than OBL-OBL. I leave these important issues unresolved in this paper.

These rules are stated in slightly different terms in the latest version of Atlamaz and Baker (2018), as a reviewer notes, and they leave out (104), yet the basics of the system remain the same. Thus, I cite the version in which the rules are more explicitly stated.

Note that taking Stem to be a case domain would also not capture the facts.

References

Andrews, Avery. 1982. The representation of case in Modern Icelandic. In The mental representation of grammatical relations, ed. Joan W. Bresnan, 427–503. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Atlamaz, Ümit. 2012. Ergative as accusative case: Evidence from Adıyaman Kurmanji. Master’s thesis, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul.

Atlamaz, Ümit, and Mark Baker. 2016. Agreement with and past oblique subjects: New considerations from Kurmanji. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 46, eds. Christopher Kimmerly and Brandon Prickett, 39–49. Amherst: GLSA.

Atlamaz, Ümit, and Mark Baker. 2018. On partial agreement and oblique case. Syntax 21 (3): 195–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12155.

Aygen, Gülşat. 2010. Zazaki/Kirmanckî Kurdish. München: Lincom Europa.

Baker, Mark. 2003. Lexical categories: Verbs, nouns and adjectives, Vol. 102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord, Vol. 115. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2015. Case: Its principles and its parameters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark, and Ümit Atlamaz. 2014. On the relationship of case to agreement in split-ergative Kurmanji and beyond. Ms., Rutgers University.

Baker, Mark C. 2011. When agreement is for number and gender but not person. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29 (4): 875–915.

Baker, Mark C, and Nadya Vinokurova. 2010. Two modalities of case assignment: Case in Sakha. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 28 (3): 593–642.

Barðdal, Jóhanna. 2001. Case in Icelandic-A synchronic, diachronic and comparative approach. PhD diss., Lund University.

Bashir, Elena. 1986. Beyond split-ergativity: Subject marking in Wakhi. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 22, 14–35. Amherst: GLSA.

Bashir, Elena. 2009. Wakhi. In The Iranian languages, ed. Gernot Windfuhr, 825–859. London: Routledge.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (1): 35–73.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2007. Ergativity in the Modern Indo-Aryan languages. Handout of a talk at MIT Ergavitivity Seminar.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2008. Where’s phi? Agreement as a post-syntactic operation. In Phi theory: Phi-features across interfaces and modules, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 295–328. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Calabrese, Andrea. 2008. On absolute and contextual syncretism: Remarks on the structure of case paradigms and on how to derive them. In Inflectional identity, eds. Asaf Bachrach and Andrew Nevins, 156–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Charnavel, Isabelle, and Dominique Sportiche. 2016. Anaphor binding: What French inanimate anaphors show. Linguistic Inquiry.

Charnavel, Isabelle Carole, and Christina Diane Zlogar. 2015. English reflexive logophors. In Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 51.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Barriers, Vol. 13. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In The view from building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–54. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In The cartography of syntactic structures: Structures and beyond, ed. Adriana Belletti, Vol. 3, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clem, Emily. 2019. Amahuaca ergative as agreement with multiple heads. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 37 (3): 785–823.

Comrie, Bernard. 1984. Reflections on verb agreement in Hindi and related languages. Linguistics 22: 857–864.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. TAM split ergativity, Part I and II. Language and Linguistics Compass 7 (3): 171–190.

Coon, Jessica, and Omer Preminger. 2017. Split ergativity is not about ergativity. In The Oxford Handbook of Ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa deMena Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Csirmaz, Aniko, and Markéta Ceplová. 2004. Other options without Optionality. In Studies in Zazaki grammar, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, Vol. 6, 11–30. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2010. Ergative case and the transitive subject: A view from Nez Perce. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 28 (1): 73–120.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2016. Person-based split ergativity in Nez Perce is syntactic. Journal of Linguistics 52 (3): 533–564.

Deo, Ashwini. 2017. On mechanisms by which languages become [nominative-] accusative. In On looking into words (and beyond): Structures, relations, analyses, eds. Claire Bowern, Laurence Horn, and Raffaella Zanuttini, 347–368. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Deo, Ashwini, and Devyani Sharma. 2006. Typological variation in the ergative morphology of Indo-Aryan languages. Linguistic Typology 10 (3): 369–418.

Despić, Miloje, and Michael D. Hamilton. 2018. Syntactic and post-syntactic aspects of Algonquian theme signs. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 48.

Dixon, Robert. 1979. Ergativity. Language 55 (1): 59–138.

Dixon, Robert. 1994. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dorleijn, Margreet. 1996. The decay of ergativity in Kurdish. Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Embick, David. 1997. Voice and the interfaces of syntax. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Embick, David. 2000. Features, syntax, and categories in the latin perfect. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (2): 185–230.

Embick, David, and Rolf Noyer. 2001. Movement operations after syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 32 (4): 555–595.

F. Sigurðsson, Einar. 2017. Deriving case, agreement and voice phenomena in syntax. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

F. Sigurðsson, Einar, Milena Šereikaite, and Marcel Pitteroff. 2018. The structural nature of the nonstructural case: Case and Passives in Lithuanian. Paper presented at Linguistic Society of America (LSA) 92.

Folli, Raffaella, and Haidi Harley. 2005. Consuming results in Italian and English: Flavors of v. In Aspectual inquiries, eds. Paula Kempchinsky and Roumyana Slabakova, 95–120. New York: Springer.

Folli, Raffaella, and Heidi Harley. 2007. Causation, obligation, and argument structure: On the nature of little v. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (2): 197–238.

Forker, Diana. 2012. The bi-absolutive construction in Nakh-Daghestanian. Folia Linguistica 46 (1): 75–108.

Gündoğdu, Songül. 2011. The phrase structure of two dialects of Kurmanji Kurdish: Standard dialect and Muş dialect. Master’s thesis, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul.

Gündoğdu, Songül. 2016. Muş Kurmancisinde ortaya çıkan farklı ergatif dizim yapıları (Different Ergative Patterns observed in Muş Kurmanji: Implications). Kürdoloji Akademik Çalışmaları 1.

Haig, Geoffrey. 1998. On the interaction of morphological and syntactic ergativity: Lessons from Kurdish. Lingua 105 (3): 149–173.

Haig, Geoffrey. 2004. Alignment in Kurdish: A diachronic perspective. Kiel: Universität zu Kiel.

Haig, Geoffrey. 2008. Alignment change in Iranian languages: A construction grammar approach, Vol. 37. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Haig, Geoffrey. 2017. Deconstructing Iranian ergativity. In The Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa deMena Travis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hale, Kenneth, and Samuel J. Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In The view from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel J. Keyser, 53–109. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from Building 20, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, Vol. 3, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Bert Vaux. 1998. Theoretical aspects of Indo-European nominal morphology: The nominal declensions of Latin and Armenian. In Mír Curad: Studies in honor of Clavert Watkins, eds. Jay Jasanoff, H. Craig Melchert, and Lisi Olivier, 223–240. Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beitraege zur Sprachwissenschaft.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78 (3): 482–526.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple agree and the defective intervention constraint in Japanese. In MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 40, 67–80.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2005. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and clausal architecture. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Holisky, Dee Ann. 1987. The case of the intransitive subject in Tsova-Tush (Batsbi). Lingua 71 (1–4): 103–132.

Holmberg, Anders, and David Odden. 2004. Ergativity and role-marking in Hawrami. Paper presented at the Syntax of the World’s Languages (SWL) 1.

Jónsson, Jóhannes Gísli. 1996. Clausal architecture and case in Icelandic. PhD diss., UMass Amherst.

Jügel, Thomas. 2009. Ergative remnants in Sorani Kurdish? Orientalia Suecana 58: 142–158.

Julien, Marit. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kalin, Laura, and Ümit Atlamaz. 2018. Reanalyzing Indo-Iranian “stems”: A case study of Adıyaman Kurmanji. In 1st Workshop on Turkish, Turkic and the languages of Turkey (Tu+1), eds. Faruk Akkuş, İsa Kerem Bayırlı, and Deniz Özyıldız.

Kareem, Rabeen Abdullah. 2016. The syntax of verbal inflection in Central Kurdish. PhD diss., Newcastle University.

Karimi, Yadgar. 2010. Unaccusative transitives and the Person-Case Constraint effects in Kurdish. Lingua 120 (3): 693–716.

Karimi, Yadgar. 2013. Extending defective intervention effects. The Linguistic Review 30 (1): 51–78.

Karimi, Yadgar. 2015. Remarks on ergativity and phase theory. Studia Linguistica. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12042.

Kaufman, Daniel. 2016. The rise and fall and rise of dependent case in Wakhi. Handout at the GC Colloquium.

Kaufman, Daniel. 2017. Double oblique case and agreement across two dialects of Wakhi. Paper presented at First North American Conference in Iranian Linguistics (NACIL) 1.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 2004. Studies in Zazaki grammar. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Korn, Agnes. 2008. Marking of arguments in Balochi ergative and mixed constructions. In Aspects of Iranian linguistics, ed. Simin Karimi, 249–276. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Laka, Itziar. 2006. Deriving split ergativity in the progressive. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Diane Massam, and Juvenal Ndayiragije, 173–196. New York: Springer.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2006. Split absolutive. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Diane Massam, and Juvenal Ndayiragije, 143–171. Dordrecht: Springer.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2008. Morphological and abstract case. Linguistic Inquiry 39 (1): 55–101.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014a. Split ergativity based on nominal type. Lingua 148: 183–212.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014b. Voice and v: Lessons from Acehnese. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2017. The locus of ergative case. In The Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa deMena Travis, 135–158. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacKenzie, David Neil. 1966. The Dialect of Awroman:(Hawrāmān-ī Luhōn); Grammatical sketch, texts and vocabulary. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

Maling, Joan, and Sigrídur Sigurjónsdóttir. 2002. The new impersonal construction in Icelandic. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 5 (1–3): 97–142.

Malmîsanij, Mehmet. 2015. Kurmancca ile Karşılaştırmalı Kırmancca (Zazaca) Dilbilgisi. Istanbul: Vate Yayınevi.

Marantz, Alec. 1991. Case and licensing. In Eighth Eastern States Conference on Linguistics (ESCOL) ‘91, eds. German F. Westphal, Benjamin Ao, and Hee-Rahk Chae, 234–253. Baltimore: ESCOL Publications.

Marantz, Alec. 1995. A late note on late insertion. In Explorations in generative grammar, eds. Young-Sun Kim, Byung-Choon Lee, Kyoung-Jae Lee, Hyun-Kwon Yang, and Jong-Yurl Yoon, Vol. 6, 396–413. Seoul: Hankuk.

Marušič, Franc, Andrew Ira Nevins, and William Badecker. 2015. The grammars of conjunction agreement in Slovenian. Syntax 18 (1): 39–77.

McFadden, Thomas. 2004. The position of morphological case in the derivation. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25 (2): 273–313.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29 (4): 939–971.

Nie, Yining. 2017. Why is there NOM-NOM and ACC-ACC but no ERG-ERG? In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 47.

Öpengin, Ergin, and Navzat Anuk. 2015. Alignment variation in Zazaki: Case-syncretisms in the Mutki dialect. In Handout at the 6th International Conference on Iranian Linguistics (ICIL) 6. Tbilisi, Georgia.

Öpengin, Ergin, and Navzat Anuk. 2016. Case syncretisms and argument coding in the Mutki dialect of Zazaki. In Handout at the 2nd conference on Zaza and Anatolian Alevi phenomenon. Yerevan, Armenia.

Oxford, Will. 2014. Microparameters of agreement: A diachronic perspective on Algonquian verb inflection. PhD diss., Universtiy of Toronto.

Oxford, Will. 2017. Inverse marking as Impoverishment. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 34, 413–422.

Paul, Daniel. 2011. A comparative dialectal description of Iranian Taleshi. PhD diss., Universtiy of Manchester.

Paul, Ludwig. 1998. Zazaki: Grammatik und Versuch einer Dialektologie. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

Paul, Ludwig. 2009. Zazaki. In The Iranian languages, ed. Gernot Windfuhr, 545–586. London: Routledge.

Payne, John R. 1980. The decay of ergativity in Pamir languages. Lingua 51 (2–3): 147–186.

Polinsky, Maria. 2017. Syntactic ergativity. In The Wiley Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures, Vol. 68. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Richards, Norvin. 2004. Zazaki Wh-Movement. In Studies in Zazaki grammar, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, Vol. 6, 77–96. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Salanova, Andrés Pablo. 2007. Nominalizations and aspect. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Selcan, Zılfi. 1998. Grammatik der Zaza-Sprache: Nord-Dialekt (Dersim-Dialekt). Berlin: Wissenschaft und Technik Verlag.

Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann. 2012. Minimalist C/case. Linguistic Inquiry 43 (1): 191–227.

Stilo, Donald. 2009. Case in Iranian: From reduction and loss to innovation and renewal. In The Oxford handbook of case, eds. Andrej Malchukov and Andrew Spencer, 700–715. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Svenonius, Peter. 2006. Case alternations and the Icelandic passive and middle. In Passives and impersonals in European languages, eds. Elsi Kaiser, Katrin Hiietam, Satu Manninen, and Verve Vihman. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Thackston, Wheeler M. 2006. Kurmanji Kurdish: A reference grammar with selected readings. Diyarbakir: Renas Media.

Todd, Terry Lynn. 2002. A grammar of Dimili: Also known as Zaza. Stockholm: Iremet Förlag.

Toosarvandani, Maziar, and Coppe Van Urk. 2014. Agreement in Zazaki and the nature of nominal concord. Ms., UC-Santa Cruz and MIT.

Windfuhr, Gernot. 2009. The Iranian languages. London: Routledge.

Wood, Jim. 2015. Icelandic morphosyntax and argument structure, Vol. 90. New York: Springer.

Woolford, Ellen. 1997. Four-way case systems: Ergative, nominative, objective and accusative. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 15 (1): 181–227.

Woolford, Ellen. 2006. Lexical case, inherent case, and argument structure. Linguistic Inquiry 37 (1): 111–130.

Yip, Moira, Joan Maling, and Ray Jackendoff. 1987. Case in tiers. Language 63: 217–250.

Zaenen, Annie, Joan Maling, and Höskuldur Thráinsson. 1985. Case and grammatical functions: The Icelandic passive. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 3 (4): 441–483.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2004. Sentential negation and negative concord. Amsterdam: LOT Publications.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Julie Anne Legate, David Embick, Akiva Bacovcin, Rajesh Bhatt, Jonathan Bobaljik, Dalina Kallulli, Laura Kalin, Songül Gündoğdu, Einar F. Sigurðsson, Daniel Kaufman, Alison Biggs, Sabine Laszakovits for their very helpful comments and suggestions. I also thank the audiences at University of Vienna, the 1st North American Conference in Iranian Linguistics (NACIL1; Stony Brook), and the participants at FMART. Thanks to three anonymous NLLT reviewers whose comments and feedback helped improve the paper greatly. I am grateful to many people for their judgments (directly or by proxy) and patience, particularly Ali Akkuş, Zemire Akkuş, Cahit Gezer, Hüseyin Baran, Gülsen Aytekin, and Necati Yağmur (Zazaki varieties); Sezgin Baran, Bilal Çetin, Songül Gündoğdu, Murat Yolun, Ümit Atlamaz, Murat Yıldırım (Kurdish varieties); Husniya Khujamyorova for Upper Wakhi (via Daniel Kaufman). Thanks also to Luke Adamson and Rob Wilder for proofreading the paper at different stages.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akkuş, F. On Iranian case and agreement. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 38, 671–727 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09457-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-019-09457-8