Abstract

Why are some linguistic inferences treated as presuppositions? This is the ‘Triggering Problem,’ which we attack from a new angle: we investigate highly iconic constructions in gestures (speech-replacing gestures or ‘pro-speech gestures’) and in signs (classifier predicates in ASL) and show that some regularly trigger presuppositions. These iconic constructions can be created and understood ‘on the fly,’ with two advantages over lexical words: they suggest the existence of a productive ‘triggering algorithm,’ since presuppositions can arguably be generated with no prior exposure to the iconic construction; and they make it possible to minimally modify the target constructions to determine which do and which do not generate presuppositions. Our investigation does not just target standard presuppositions, but also ‘cosuppositions,’ initially defined as conditionalized presuppositions triggered by co-speech gestures. We show that pro-speech gestures and classifier predicates alike can trigger cosuppositions, which are thus an inferential class that goes beyond the confines of co-speech gestures (Aristodemo 2017). Our data argue for a triggering algorithm that can generate presuppositions on iconic grounds, and we offer a generalization of cosupposition theory on which these can be triggered for reasons of manner (co-speech gestures), but also for conceptual reasons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While one may take the co in cosupposition to be mnemonic for ‘conditionalized,’ the latinate prefix is justified as follows: a standard presupposition p of an expression pp′ must be satisfied before one has access to the at-issue component \(p'\), whereas a cosupposition can be satisfied with (thanks to) the at-issue component (see Schlenker 2018a, Sect. 3.2, for relevant remarks).

The intuition behind this initial theory is that co-speech gestures do not come with their own time slot and are secondary relative to the main modality, hence are presented as being omissible without truth-conditional loss. This is the case precisely when their content is presupposed to follow from the modified expression.

Other paradigms, discussed in Sect. 5.5, provide clearer data about pro-speech cosuppositions disregarded under ellipsis.

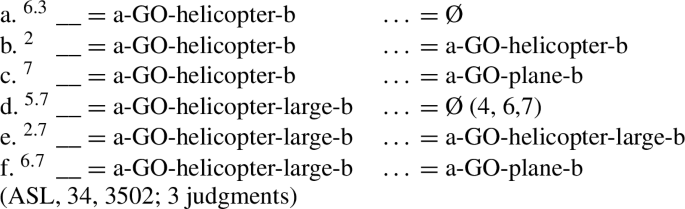

Notations such as ASL, 34, 1550a,e, 5 judgments indicate that the relevant sentences appeared in ASL video 34, 1550, that only sentences a and e (i.e. the first and the fifth) from that paradigm are transcribed, and that averages are computed on the basis of 5 judgments (if no letters followed 34, 1550, this would indicate that the entire paradigm was transcribed).

We use the term ‘consultant’ for our ASL consultant (and occasional co-author), who helps construct judgments and is involved in a long-term collaboration. We use the term ‘informant’ for linguists we surveyed in a more ad hoc fashion (though one of them helped with the construction of the data).

This section borrows from Sect. 3.2 of Schlenker (2018b)

This paragraph borrows from parts of Sect. 4.1.2 of Schlenker (2019a)

The content of this summary is partly similar to one that appears in Schlenker (2018c)

As Jonathan Lamberton (p.c.) notes, the realization of the 2-rotored (and 2-handed) helicopter varied: sometimes both hands were faced toward locus b, sometimes the hands faced each other. The difference is immaterial for our purposes and thus it is not transcribed in the glosses.

Since the universal inference asymmetrically entails the existential inference, it is expected that the latter should be endorsed at least as strongly as the former. But the difference in endorsement strengths is rather striking in this case.

In addition, the predicate classifier starts a bit higher in this case than in some other conditions.

Typically focus in ASL also involves raised eyebrows, which are not present in our examples, but this doesn’t preclude the possibility that manual intensification without raised eyebrows could mark focus as well. As Wilbur (1999) notes, in ASL “the primary indicator of stress marking is the significant increase in peak velocity of prominent signs.”

One could argue that longer duration can be used to mark focus (e.g. Schlenker et al. 2016). Thus one could try to analyze this example as well as involving a kind of focus on the hovering part, which would make it necessary to study further ‘focus-free’ paradigms in the future.

There was a false start for (30) (… WITH PAUSE…): the consultant aborts a sentence and immediately starts again.

Our consultant noted that the inferential part of his task was made easier, not harder, by using quantitative judgments of inferential strength. Without these, he had to reflect at length about how to categorize judgments of intermediate strength; the quantitative method allowed for less arbitrary decisions in such cases. (The fact that our consultant has many years of experience with introspective judgments might of course have played a role in this impression.)

Two remarks should be added. In the general case, graded inferential judgments “may help detect otherwise hidden effects,” as is explicitly discussed by Cremers and Chemla (2017). In addition, quantitative assessment is particularly important in work on presuppositions because presupposition triggers can give rise to ‘local accommodation’ (= the phenomenon by which, at some cost, a presupposition gets turned into an at-issue contribution and fails to project; Beaver 2010; Tonhauser et al. 2018). As a result, presuppositional effects can be subtle, in a way that depends on the trigger (descriptively, some triggers are more conducive to local accommodation than others). Detecting subtle inferential effects is thus of the essence.

According to Stalnaker (1978), an expression should not be trivial relative to (i.e. follow from) its local context. On the assumption that the local context of the modifier includes the semantic content of the verb it modifies, we obtain the condition that The helicopter took off should not be presupposed to entail The helicopter took off with movement X. Technically, this non-triviality requirement is an antipresupposition (Sauerland 2003, 2008; Percus 2006; Singh 2011; Schlenker 2012; Anvari 2018). For a derivation of the deviance of related cases in which a complex expression competes with structurally simpler alternatives, see Katzir (2007) and Katzir and Fox (2011).

It is worth noting that the problem discussed in this section (to the effect that controls could be responsible for the desired) is pervasive in presupposition theory. For instance, in (14) above, we argued for the presuppositional behavior of the English verb take off by displaying a contrast between Will the company’s plane take off? and Will the company’s plane be on the ground and then take off? The traditional idea is that in the second sentence the underlined expression is at-issue and justifies the presupposition of take off, with the result that the entire conjunction is presuppositionless, hence should not give rise to a projection behavior. But the first conjunct comes with its own non-triviality requirement: it should not be presupposed that the plane is on the ground (this case immediately follows from conditions stated in Stalnaker 1978, see fn. 19). The contrast between the target and the at-issue control is thus due in part to this antipresupposition.

See fn. 15 for some qualifications, however.

As an anonymous reviewer points out, this method could introduce biases due to the subjects’ training as linguists. We take this survey to be just a first step, which should be extended with experimental methods in the future.

The manual gesture need not be realized exactly in the same way in b. and in c.

We do not discuss here an additional part of our gesture survey, which pertained to pro-speech music, in the form of a song (the first words of the French national anthem) replacing a verb, as illustrated in (i)a:

-

(i)

On Bastille Day, will your students

-

a.

?

? -

b.

?

? -

c.

?

? -

d.

sing the Marseillaise with

[this] posture?

[this] posture?

-

a.

In (i)a, the French words Allons enfants de la patrie are literally sung as part of the sentence. In (i)b, they are sung in a reluctant and unmusical fashion. In (i)c, they are sung normally, but are accompanied by a patriotic posture, with the speaker’s hand on his heart. (i)d is a control in which this position co-occurs with (and is the denotation of) this posture.

As can be seen in the Supplementary Materials B, (i)c and related embedding tests suggest that the posture triggers a cosupposition to the effect that if the speaker’s students were to sing the Marseillaise on Bastille Day, they would adopt a patriotic posture such as having one’s hand on one’s heart. On the other hand, the unmusical rendering of the song in (i)b only triggers a much weaker cosupposition (to the effect that, if the relevant students were to sing, they would do so in a reluctant/unmusical fashion).

-

(i)

Schlenker (2015) notes that the ‘disappearing act’ of co-speech gestures can be replicated in the ‘focus dimension’ under only. Here we solely discuss ellipsis, but only and other particles that associate with focus should be studied in the future. (Ellipsis is particularly important for the present discussion because it is used by Aristodemo 2017 to argue that some of her LIS constructions might involve incorporated gestures.)

Aristodemo and Santoro (2018) summarize Aristodemo’s findings and provide further examples in which iconic material under Role Shift (a construction that has sometimes been treated as overt context shift, e.g. by Quer 2005, 2013 and Schlenker 2017a,b); here we only discuss data from Aristodemo (2017).

Similarly, one would need to posit that the ‘focus dimension’ under only is computed in a way that makes it possible to ignore gestures.

Aristodemo’s dissertation has ‘Piero’s glass’ rather than ‘my glass’ in the translation, but this is evidently a typo, which we have corrected. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for noticing the error, and to V. Aristodemo (p.c.) for confirming that this was indeed a typo.

The paradigm that appears in the Supplementary Materials B is summarized in (i):

-

(i)

Your son, I won’t ____, but your daughter, I will.

-

a.

-

b.

-

c.

lift with this kind of face

(video 13)

-

a.

The crucial condition is in (ib). It gives rise to the inference that if the speaker were to lift the addressee’s son, a disgusted expression would be involved, but not that the speaker will lift the addressee’s daughter with a disgusted expression.

-

(i)

The survey erroneously contains ‘fat’ instead of ‘big.’

We could solve this problem by replacing will with might in (45) and (46): this would make the conditionalized inference entirely felicitous. But as we explain in greater detail in fn. 55 of Appendix 2 for an analogous case in ASL, embedding the elided clause in this way would cause problems of its own (because presuppositional inferences could fail to be drawn for two separate reasons: disappearance under ellipsis, or local accommodation).

Simplifying somewhat, the key condition is stated in (i) (Abrusán explicitly defines a version of the relevant notions for a first-order logic):

-

(i)

A sentence S is not about an object o just in case for every model M,

S is true in M if and only if for every model M′ which is an o-variant of M, S is true in M′.

A model M′ is an o-variant of a model M just in case for every relation symbol R, the extension of R is made of the same tuples of objects in M′ as in M, except possibly for those tuples that include object o.

-

(i)

One could obtain the same result with a weaker alternative, a gesture

to the effect that the relevant agent has hands on a wheel (irrespective of whether the agent turned the wheel or not). If x

to the effect that the relevant agent has hands on a wheel (irrespective of whether the agent turned the wheel or not). If x  has the content that x has their hands on a wheel, the disjunction (x

has the content that x has their hands on a wheel, the disjunction (x  or x

or x  ) will again yield the desired result.

) will again yield the desired result.Similar issues are raised by change of state verbs presupposing the initial state, such as the pro-speech gesture or classifier predicate involving a take-off. Abusch’s theory can account for them if their alternatives involve a helicopter doing various things starting from the same initial state—including just staying put; but this would need to be derived.

One might want to test what the event time is by modifying the sentence so as to include a precise temporal modifier—for instance one meaning at 5:05pm sharp—and determining whether it unambiguously specifies the time of the subevent (the pause, or the deviation) rather than of the entire event. But it might well be that for independent reasons a modifier would be constrained to modify the at-issue component of the predicate, in which case a positive result (to the effect that the precise modifier provides information about the time of the pause, or of the deviation) would not be informative. We leave this question for future research.

‘Elementary’ is crucial: we want to predict a presupposition for the elementary expression stopped in John stopped smoking, but not for the complex conjunction in John smoked and stopped.

This should be read as follows: in each world w that is in C and satisfies the (classical, non-presuppositional) meaning of pp′, w makes true the counterfactual conditional (not pp′) → p.

We discuss what we take to be plausible results of the counterfactual tests. Importantly, these could be more rigorously assessed independently from the presuppositional data that we seek to derive.

Potts et al. 2009 contrast the case of the underlined expressive in (i)A, which can be ignored under ellipsis in (i)B, to the prenominal modifier in (ii)A, which cannot be ignored in a similar fashion in (ii)B.

-

(i)

A: I saw your fucking dog in the park.

B: No, you didn’t—you couldn’t have. The poor thing passed away last week. (Potts et al. 2009)

-

(ii)

A: I saw a shaggy dog in the park.

B: I did too. #The one I saw/It had no hair. (Potts et al. 2009)

-

(i)

This theory would not explain the difference between our ellipsis data for ASL classifier predicates and for English pro-speech gestures, but at this point this a mystery for every analysis.

A different but formally related theory was suggested by an anonymous reviewer. Maybe cosupposition-inducing iconic expressions are syntactically decomposed into a verbal element and a manner adverbial that is high enough to be ignored under ellipsis. This theory seems to us strictly worse than the incorporated gesture analysis, for two reasons: (i) it fails to explain why these manner adverbials trigger cosuppositions; this is all the more striking since explicit manner adverbials fail to trigger them, both in our ASL and in our English data; (ii) one would need to posit that a manner modifier corresponding to a shape modulation realized throughout or in the middle of the iconic expressions (as was the case in our cosupposition-inducing classifiers and pro-speech gestures) is syntactically attached high, and there is no evidence for this.

Thanks to M. Esipova (p.c.) for noticing a typo in an earlier formulation. (Esipova 2019 discusses a more general statement of the equivalence, for the case in which the modifiers are not intersective.)

An anonymous reviewer suggests that some cases of co-speech gestures that give rise to local accommodation (hence no cosupposition in the end) could be treated differently, by positing that their content is treated as important, for instance for reasons of focus (as in Esipova 2017). If so, these are not cases of accommodated cosuppositions, but rather cases in which the cosuppositional inference isn’t generated to begin with. Note that on this variant of our analysis, one still needs a presumption that co-speech gestures provide unimportant information, or else we would not derive the crucial contrast in (61).

In greater detail, let us write I will lift the child as p and I will lift the child as depicted as pp′. In order to guarantee that the question under discussion is addressed by a ‘no’ (as well as a ‘yes’) answer in (63), we need a presupposition that we are not in the hatched area, corresponding to (p ∧¬ pp′), hence: ¬(p ∧¬ pp′), which simplifies to (¬p ∨ pp′), i.e. p ⇒ p′; this is the desired cosupposition.

We also leave for future research an investigation of demonstratives referring to gestures, as in (i). Our impression is that this construction fails to trigger the expected cosuppositions, possibly because the demonstrative highlights that all aspects of the iconic representation are important and thus at-issue.

-

(i)

At 12:05, our company’s helicopter won’t do this:

-

(i)

M. Esipova (p.c.) made a related remark in a slightly different context.

We have another worry. On the proposed theory, the at-issue content of the pro-speech gesture should be entailed by the covert word. Examples such as (i) might pose a problem because gesture is hard to paraphrase.

-

(i)

Context: While a painter is away, two of her friends are discussing an unfinished painting of hers. In order to complete this abstract painting, do you think our friend will

?

?

We believe that this pro-speech gesture can have an at-issue component that indicates a specific abstract shape, one that could not be described in gesture-free words. Simultaneously, one can realize the gesture in a very slow and deliberate way so as to suggest, arguably in a cosuppositional fashion, that if our friend were to draw this shape, a slow and deliberate movement would be involved. It is hard to see which covert word could ensure that the shape is at-issue but the manner of painting is not. (We would have to posit a covert expression that makes demonstrative reference the gesture, e.g.:

draw this. The shape could then be at-issue because it is entailed by the covert expression, while the manner of painting could be cosuppositional because it isn’t so entailed…)-

(i)

Things are more complicated if we take the circling motion to be due to the situation rather than to the helicopter, as this entailment might not be counterfactually stable any more.

Finally, as mentioned in Sect. 3.6.2, it should be kept in mind that, as in all studies of presuppositions, the inferential contrasts we obtain are due to the difference between the target constructions and the at-issue controls, which typically come with anti-presuppositions. This could pave the way for accounts based on general pragmatic reasoning: pragmatic enrichment might be plausible in all cases (e.g. one raises the possibility that pp′ because p is generally the case), but defeated in the controls (in case p is presented as non-trivial). We leave this issue for future research.

As shown in the Supplementary Materials, initial questions did not ask for quantitative inferential judgments; for uniformity with the other paradigms discussed in this piece, only the judgment tasks that included quantitative inferential questions are taken into account here.

IX-arc appears to be signed in a neutral position, so no locus is assigned to it.

To see why we made this decision, consider the condition in (72)b, involving a swaying movement. On the basis of the inferences triggered by the antecedent clause (about the signer’s company’s helicopter), we can determine that the ‘swaying movement’ inference is a cosupposition. The question is whether it is preserved under ellipsis. If the elided clause included MAYBE, there would be two potential reasons why this inference could fail to arise: (i) because it just isn’t preserved under ellipsis; (ii) because it gives rise to local accommodation (and is thus treated as part of the at-issue component) in the scope of MAYBE within the elided clause. Possibility (ii) is a significant worry because cosuppositions are often taken to be weak presuppositions (which means that they are easily turned into part of the at-issue component). It is to avoid this attenuation of the effects that we did not include MAYBE in the clause with the elided VP: whether there is local accommodation or not, the ‘swaying’ inference should show up if it is preserved under ellipsis. (With more fine-grained data, one could include MAYBE in the elided clause and assess the difference between the strength of the cosuppositional inference in the elided clause and in the antecedent, with the assumption that local accommodation should target both conditions in comparable ways.)

The following general directions could be explored.

(i) There could be a kind of agreement relation between the noun HELICOPTER and the predicate classifier. But this explain (77)d, where there is a mismatch between the noun HELICOPTER (which is neutral) and the predicate classifier, which is 2-rotored.

(ii) Another possibility is that, for our consultant at least, ellipsis is very liberal and allows for any material that is redundant to be disregarded under ellipsis. This proposal was made for ASL in Schlenker 2014 and Schlenker, 2018d.

(iii) Yet another possibility is that the inference about object shape is in fact a cosupposition, but that it gets strengthened due to world knowledge. The idea would be as follows: suppose we obtain an inference to the effect that if the helicopter flies, it will have two rotors. The only plausible way to justify this condition is to assume that the helicopter has two rotors, whether it flies or not. But this analysis only helps if classifier predicate cosuppositions can in fact be ignored under ellipsis, which isn’t clear for our ASL consultant.

(iv) Finally, we find it plausible that the helicopter path is really decomposed (whether syntactically or just conceptually) as being made of two parts: one corresponds to the object shape, and the other to the path. Under this decompositional view, it is relatively unsurprising that one can to some extent recover the path without the object shape under ellipsis.

References

Abrusán, Márta. 2011. Predicting the presuppositions of soft triggers. Linguistics and Philosophy 34(6): 491–535.

Abusch, Dorit. 2002. Lexical alternatives as a source of pragmatic presuppositions. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 12, ed. Brendan Jackson. Cornell University: CLC Publications.

Abusch, Dorit. 2010. Presupposition triggering from alternatives. Journal of Semantics 27(1): 37–80.

Anvari, Amir. 2018. Logical integrity. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 28, eds. Sireemas Maspong, Brynhildur Stefánsdóttir, Katherine Blake, and Forrest Davis, 711–726.

Aristodemo, Valentina. 2017. Gradable constructions in Italian sign language. PhD diss., EHESS.

Aristodemo, Valentina, and Mirko Santoro. 2018. Iconic components as gestural elements: The case of LIS. Theoretical Linguistics 44(3–4): 209–213.

Beaver, David I. 2001. Presupposition and assertion in dynamic semantics. Stanford: CSLI.

Beaver, David I. 2010. Have you noticed that your belly button lint colour is related to the colour of your clothing? In Presuppositions and discourse: Essays offered to Hans Kamp, eds. Reyle Bäuerle, Uwe Reyle, and Thomas E. Zimmermann, 65–99. Oxford: Elsevier.

Beaver, David I., Craige Roberts, Mandy Simons, and Judith Tonhauser. 2017. Questions under discussion: Where information structure meets projective content. Annual Review of Linguistics 3(1): 265–284.

Brentari, Diane. 2018. Modality and contextual salience in co-sign vs. co-speech gesture. Theoretical Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2018-0014.

Büring, Daniel. 2012. Focus and intonation. In Routledge companion to the philosophy of language, eds. Gillian Russell and Delia Graff Fara, 103–115. London: Routledge.

Chemla, Emmanuel. 2009. Presuppositions of quantified sentences: Experimental data. Natural Language Semantics 17(4): 299–340.

Chemla, Emmanuel. 2010. Similarity: Towards a unified account of scalar implicatures, free choice permission and presupposition projection. Unpublished manuscript. LSCP, Paris.

Cremers, Alexandre, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2017. Experiments on the acceptability and possible readings of questions embedded under emotive-factives. Natural Language Semantics 25(3): 223–261.

Davidson, Kathryn. 2015. Quotation, demonstration, and iconicity. Linguistics and Philosophy 38(6): 477–520.

Ebert, Cornelia, and Christian Ebert. 2014. Gestures, demonstratives, and the attributive/referential distinction. Handout of a talk given at Semantics and Philosophy in Europe (SPE 7), Berlin, June 28, 2014.

Emmorey, Karen, and Melissa Herzig. 2003. Categorical versus gradient properties of classifier constructions in ASL. In Perspectives on classifier constructions in signed languages, ed. Karen Emmorey, 222–246. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Esipova, Maria. 2017. Focus on what’s not at issue: Gestures, presuppositions, supplements under Contrastive Focus. Talk given at Sinn und Bedeutung 2017, Berlin-Potsdam.

Esipova, Maria. 2019. Composition and projection in speech and gesture. PhD diss., New York University.

Heim, Irene. 1983. On the projection problem for presuppositions. In West coast conference on formal linguistics (WCCFL) 2, eds. Michael Barlow, Daniel Flickinger, and Michael Westcoat, 114–126. Stanford: CSLI.

Katzir, Roni. 2007. Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30(6): 669–690.

Katzir, Roni, and Danny Fox. 2011. On the characterization of alternative. Natural Language Semantics 19(1): 87–107.

Lewis, David. 1973. Counterfactuals. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

McCawley, James D. 1998. The syntactic phenomena of English, 2nd edn. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Percus, Orin. 2006. Anti-presuppositions. In Theoretical and empirical studies of reference and anaphora: Toward the establishment of generative grammar as an empirical science, ed. Ayumi Ueyama, 52–73. Report of the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Project No. 15320052, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Potts, Christopher, Ash Asudeh, Seth Cable, et al.. 2009. Expressives and identity conditions. Linguistic Inquiry 40(2): 356–366.

Quer, Josep. 2005. Context shift and indexical variables in sign languages. In Semantic and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 15, Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Quer, Josep. 2013. Attitude ascriptions in sign languages and role shift. In 13th meeting of the Texas linguistics society, ed. Leah C. Geer, 12–28. Austin: Texas Linguistics Forum.

Romoli, Jacopo. 2014. The presuppositions of soft triggers are obligatory scalar implicatures. Journal of Semantics 1: 1–47.

Rooth, Mats. 1996. Focus. In Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory, ed. Lappin. Blackwell.

Sauerland, Uli. 2003. Implicated presuppositions. Handout for a talk presented at the University of Milan Bicocca.

Sauerland, Uli. 2008. Implicated presuppositions. In Sentence and context: Language, context, and cognition, ed. Anita Steube. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2009. Local contexts. Semantics and Pragmatics 2: 3. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.2.3.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2010. Supplements within a unidimensional semantics I: Scope. In Logic, language and meaning: 17th Amsterdam colloquium, eds. Maria Aloni, Harald Bastiaanse, Tikitu de Jager, and Katrin Schulz, 74–83. Amsterdam: Springer. Revised Selected Papers.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2012. Maximize presupposition and Gricean reasoning. Natural Language Semantics 20(4): 391–429.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2014. Iconic features. Natural Language Semantics 22(4): 299–356.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2015. Gestural presuppositions. Snippets 30. https://doi.org/10.7358/snip2015-030-schl.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2017a. Super monsters I: Attitude and action role shift in sign language. Semantics and Pragmatics 10: 9.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2017b. Super monsters II: Role shift, iconicity and quotation in sign language. Semantics and Pragmatics 10: 12.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2018a. Gesture projection and cosuppositions. Linguistics and Philosophy 41(3): 295–365.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2018b. Iconic pragmatics. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36(3): 877–936.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2018c. Sign language semantics: Problems and prospects. Theoretical Linguistics 44(3–4): 295–353.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2018d. Locative shift. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3(1): 115. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.561.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2019a. Gestural semantics: Replicating the typology of linguistic inferences with pro- and post-speech gestures. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37(2): 735–784.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2019b. Gestural cosuppositions within the transparency theory. Linguistic Inquiry 50(4): 873–884.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2019c. What is Super Semantics? Philosophical Perspectives 32(1): 365–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpe.12122.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2019d. Musical meaning within Super Semantics. Ms., Institut Jean-Nicod and New York University.

Schlenker, Philippe. To appear. The semantics and pragmatics of appositives. In Companion to semantics, eds. Lisa Matthewson, Cécile Meier, Hotze Rullmann, and Thomas Ede Zimmermann. Hoboken: Wiley.

Schlenker, Philippe, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2018. Gestural agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36(2): 587–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9378-8.

Schlenker, Philippe, Jonathan Lamberton, and Mirko Santoro. 2013. Iconic variables. Linguistics and Philosophy 36(2): 91–149.

Schlenker, Philippe, Valentina Aristodemo, Ludovic Ducasse, Jonathan Lamberton, and Mirko Santoro. 2016. The unity of focus: Evidence from sign language. Linguistic Inquiry 47(2): 363–381.

Simons, Mandy. 2001. On the conversational basis of some presuppositions. In Semantics and linguistic theory (SALT) 11, eds. Rachel Hastings, Brendan Jackson, and Zsofia Zvolenszky, 431–448.

Simons, Mandy. 2003. Presupposition and accommodation: Understanding the Stalnakerian picture. Philosophical Studies 112: 251–278. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023004203043.

Simons, Mandy, David Beaver, Craige Roberts, and Judith Tonhauser. 2010. What projects and why. In Semantics and linguistic theory (SALT) 20, eds. Nan Li and David Lutz, 309–327. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Sprouse, Jon, and Diogo Almeida. 2012. Assessing the reliability of textbook data in syntax: Adger’s Core Syntax. Journal of Linguistics 48: 609–652.

Sprouse, Jon, and Diogo Almeida. 2013. The empirical status of data in syntax: A reply to Gibson and Fedorenko. Language and Cognitive Processes. 28: 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2012.703782.

Sprouse, Jon, Carson T. Schütze, and Diogo Almeida. 2013. A comparison of informal and formal acceptability judgments using a random sample from Linguistic Inquiry 2001–2010. Lingua 134: 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.07.002.

Singh, Raj. 2011. Maximize presupposition! and local contexts. Natural Language Semantics 19(2): 149–168.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1968. A theory of conditionals. In Studies in logical theory. Vol. 2 of American philosophical quarterly, monograph.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1974. Pragmatic presuppositions. In Semantics & philosophy, eds. Milton Munitz and Peter Unger. New York: New York University Press.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1978. Assertion. In Syntax and semantics 9. New York: Academic Press.

Tieu, Lyn, Robert Pasternak, Philippe Schlenker, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2017. Co-speech gesture projection: Evidence from truth-value judgment and picture selection tasks. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 2(1): 102.

Tieu, Lyn, Robert Pasternak, Philippe Schlenker, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2018. Co-speech gesture projection: Evidence from inferential judgments. Glossa 3(1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.580.

Tieu, Lyn, Philippe Schlenker, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2019. Linguistic inferences without words. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(20): 9796–9801.

Thomason, Richmond, Matthew Stone, and David DeVault. 2006. Enlightened update: A computational architecture for presupposition and other pragmatic phenomena. In Presupposition Accommodation, eds. Donna Byron, Craige Roberts, and Scott Schwenter. Prepublication version distributed by Ohio State Pragmatics Initiative, forthcoming (http://ling.osu.edu/pragwiki/ index.php).

Tonhauser, Judith, David Beaver, and Judith Degen. 2018. How projective is projective content? Journal of Semantics 35: 495–542.

Wilbur, Ronnie B. 1999. Stress in ASL: Empirical evidence and linguistic issues. Language and Speech 42(2–3): 229–250.

Zucchi, Sandro. 2011. Event descriptions and classifier predicates in sign languages. Presentation at FEAST (Formal and Experimental Advances in Sign language Theory) in Venice, June 21, 2011.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Emmanuel Chemla and Lyn Tieu for detailed discussions of every aspect of this piece, and for their considerable patience in discussing examples. Brian Buccola and Rob Pasternak were also very generous in providing numerous acceptability and inferential judgments. Salvador Mascarenhas helped with several examples as well. In addition, I benefited from the suggestions of colleagues at the UCL Workshop on Sign, Gesture and Language (January 31, 2018). I also wish to thank the researchers who, over the years, urged me to compare iconic effect in sign language to iconic gestures (this includes Adam Schembri, Diane Lillo-Martin, Kathryn Davidson, Benjamin Spector and Cornelia Ebert); special thanks as well to Masha Esipova, who made helpful comments on several aspects of this research. Finally, I am very grateful to anonymous reviewers for Natural Language & Linguistic Theory and to handling Editor Gillian Ramchand for many helpful criticisms and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ASL consultant for this article: Jonathan Lamberton. Special thanks to Jonathan Lamberton, who provided exceptionally fine-grained data throughout this research; his contribution as a consultant was considerable. He also provided or corrected transcriptions and translations of ASL examples. I am particularly grateful to him for authorizing me to provide lightly anonymized videos of some crucial examples.

Grant acknowledgments: The research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement N°324115–FRONTSEM (PI: Schlenker), and also under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (ERC grant agreement No 788077, Orisem, PI: Schlenker). Research was conducted at Institut d’Etudes Cognitives, Ecole Normale Supérieure - PSL Research University. Institut d’Etudes Cognitives is supported by grant FrontCog ANR-17-EURE-0017.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Appendices

Appendix 1: Comparing lexical triggers and iconic triggers in ASL

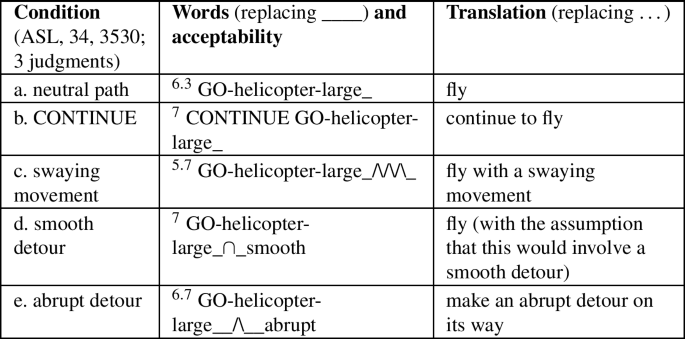

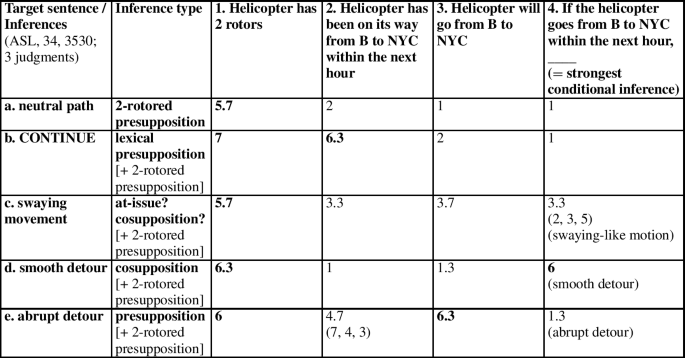

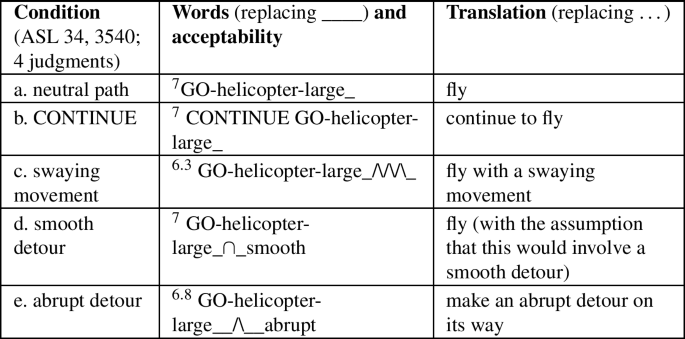

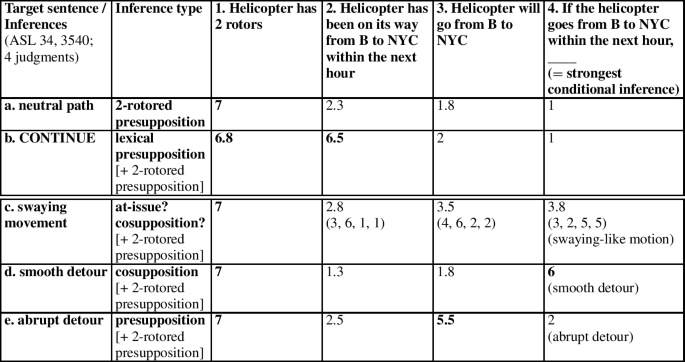

We provide below some details about the paradigms discussed in Sect. 3. As in the main text, we boldface inferential strengths that are at or above 5.

❑ Going from Boston to New York: embedding under DOUBT, MAYBE, IF, and NONE

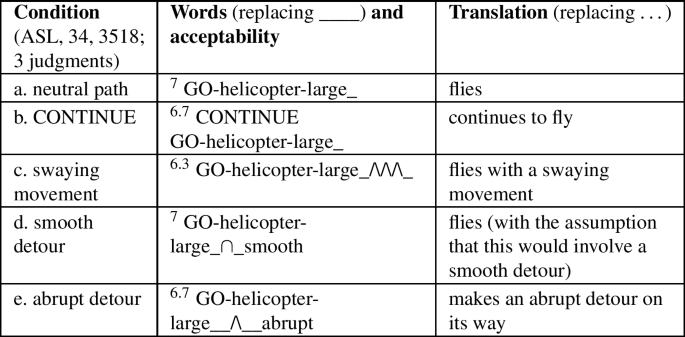

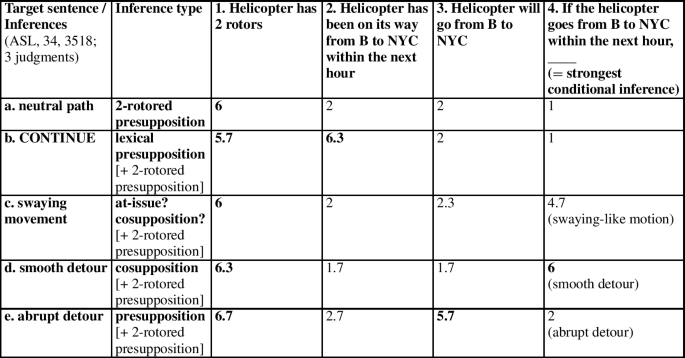

We start with details about our paradigm involving horizontal movement of a helicopter from New York to Boston. We do not repeat the inferential questions, introduced in (19) and (20) in the text (see also the Supplementary materials, where all inferential questions are copied).

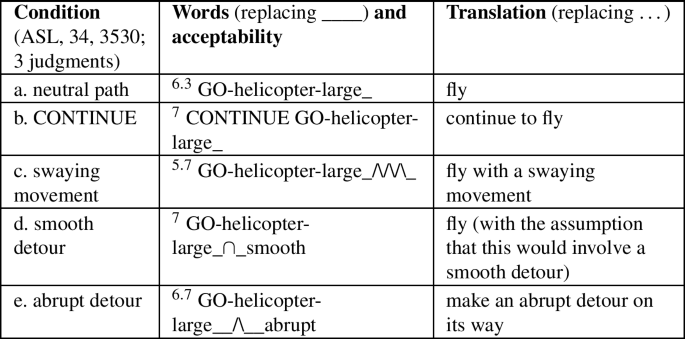

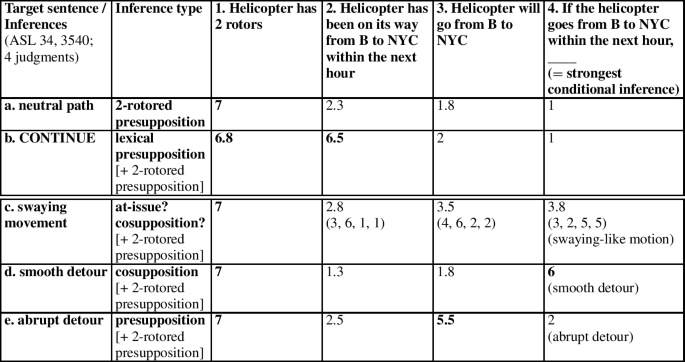

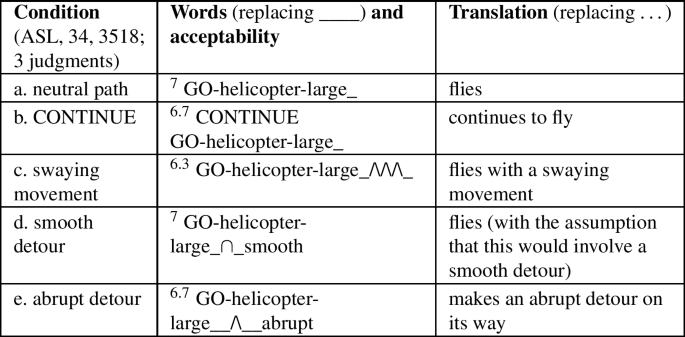

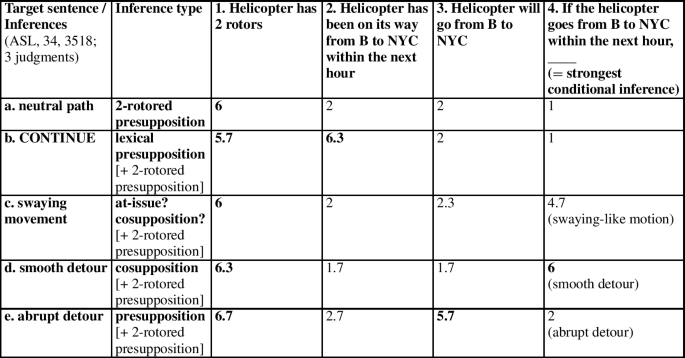

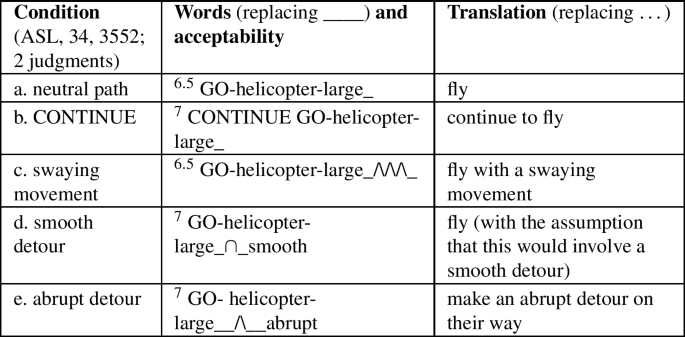

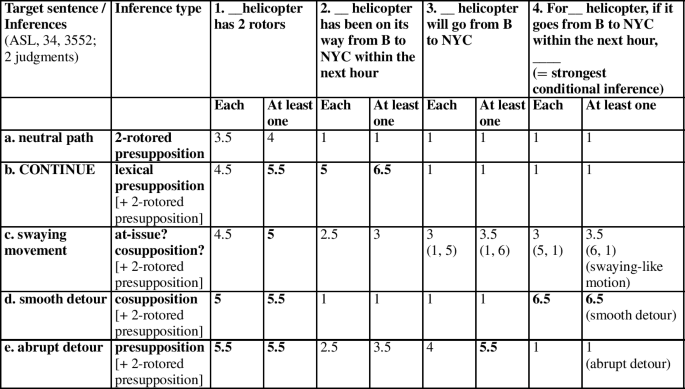

The inferential data for embedding under DOUBT in (64), under MAYBE in (65) and under IF in (66) all lead to the same general conclusions. First, the 2-rotored representation of the helicopter triggers a presupposition (in all cases), as does CONTINUE (to the effect that the helicopter has been on its way from Boston to New York). Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the ‘swaying movement’ condition does not trigger a cosupposition (or any presupposition besides the 2-rotored one). By contrast, the ‘smooth detour’ condition triggers a cosupposition to the effect that if the helicopter were to go from Boston to New York within the next hour, this would involve a smooth detour. Finally, the ‘abrupt detour’ condition triggers a presupposition that the helicopter will in fact go from Boston to New York within the next hour.

Data pertaining to embedding under NONE are harder to assess. First, we only have two judgments in this case. Second, several cases give rise to much variability. Still, CONTINUE does seem to trigger the expected presupposition, whether one uses existential projection or universal projection as a criterion. The same conclusion holds of the ‘smooth detour’ cosupposition. Using existential projection as a criterion, the 2-rotored presupposition emerges in some but not in all cases, and the presupposition that the helicopter will in fact go from Boston to New York in the next hour does emerge in the ‘abrupt detour’ condition.

-

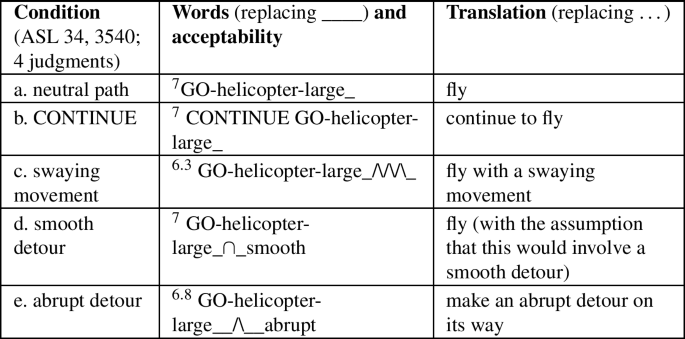

(64)

DOUBT

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane.

WITHIN 1-HOUR OUR COMPANY BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKb DOUBT ___.

‘I doubt that within an hour our company’s big helicopter will … from Boston to New York.’ (ASL, 34, 3530; 3 judgments)

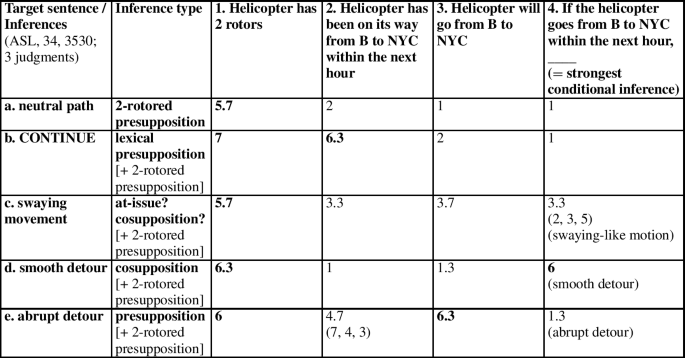

-

(65)

MAYBE

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane.

WITHIN 1-HOUR OUR COMPANY BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKb MAYBE ___.

‘Within an hour, maybe our company’s big helicopter will … from Boston to New York.’ (ASL 34, 3540; 4 judgments)

-

(66)

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane.

WITHIN 1-HOUR OUR COMPANY BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKb IF ___, 2-E-MAIL-1.

‘If within an hour our company’s big helicopter … from Boston to New York, e-mail me.’ (ASL, 34, 3518 3 judgments)

-

(67)

NONE

Context: our company has four helicopters and one airplane.

WITHIN 1-HOUR OUR COMPANY 4 BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKb NONE IX-arcFootnote 51 ___.

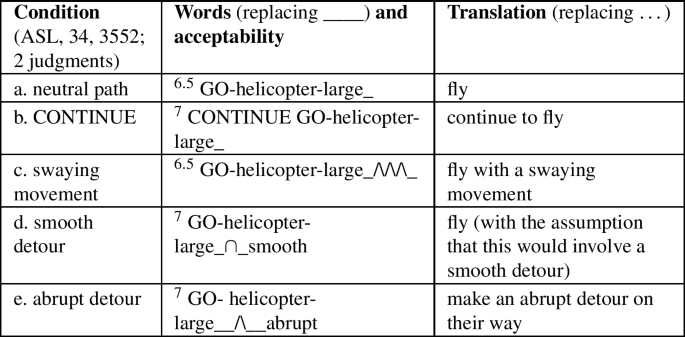

‘Within the next hour, none of our company’s 4 big helicopters will … from Boston to New York.’ (ASL, 34, 3552; 2 judgments)

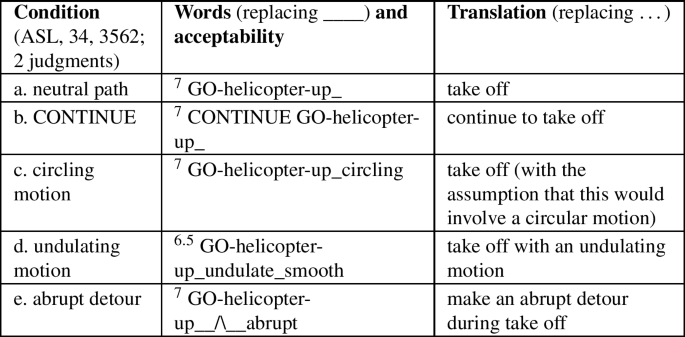

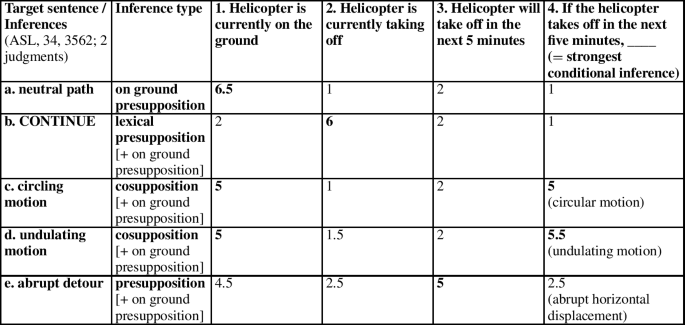

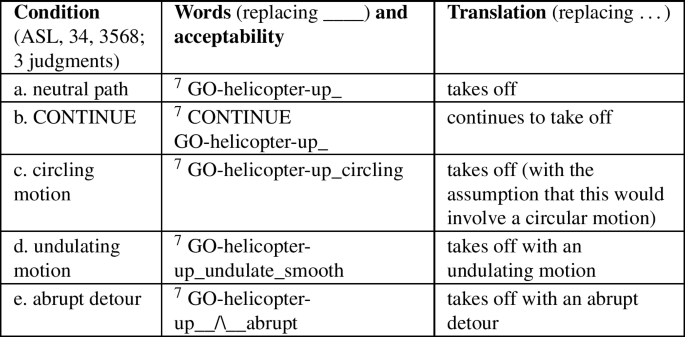

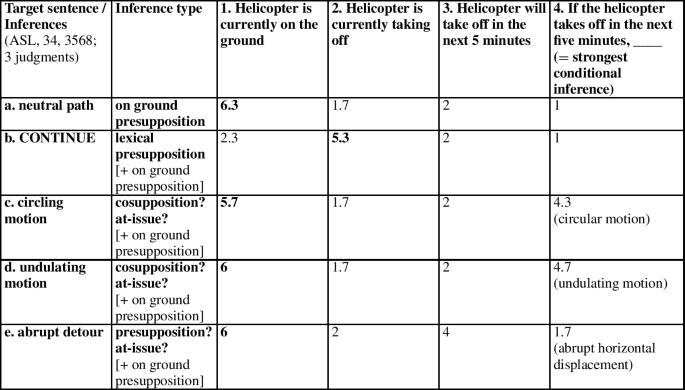

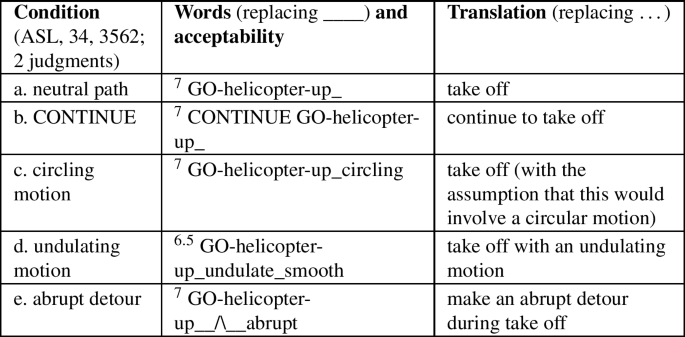

❑ Taking off: embedding under DOUBT, MAYBE, IF, and NONE

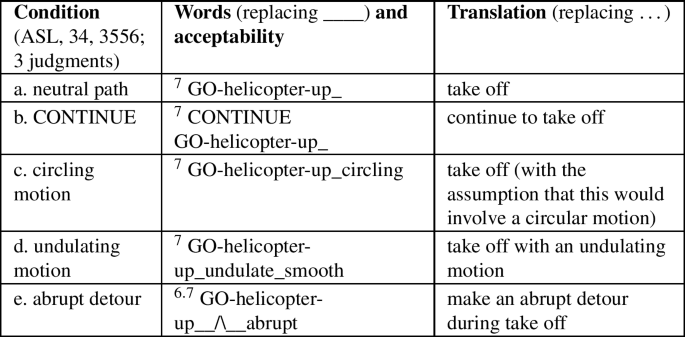

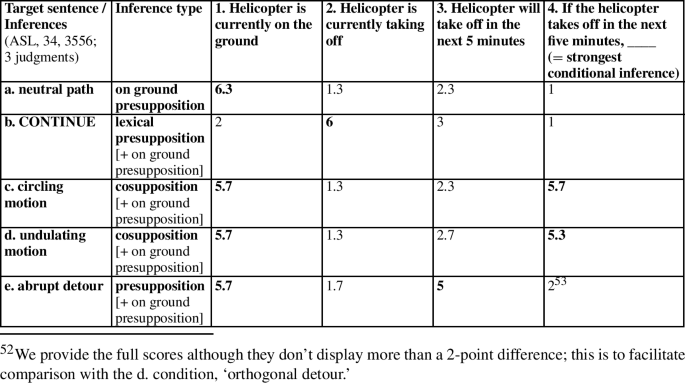

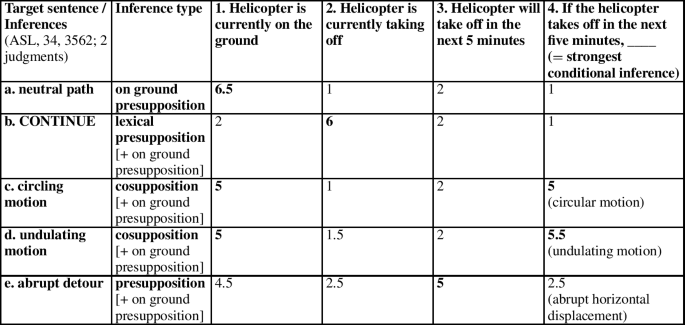

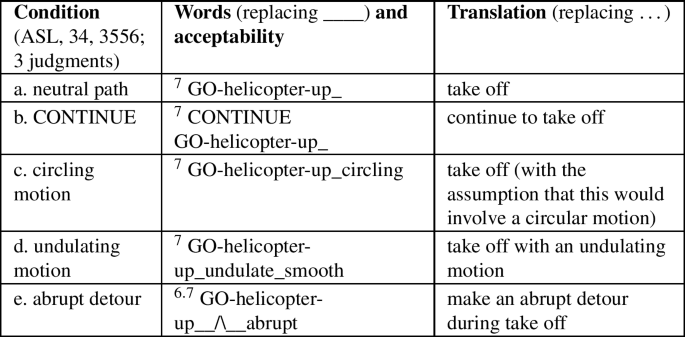

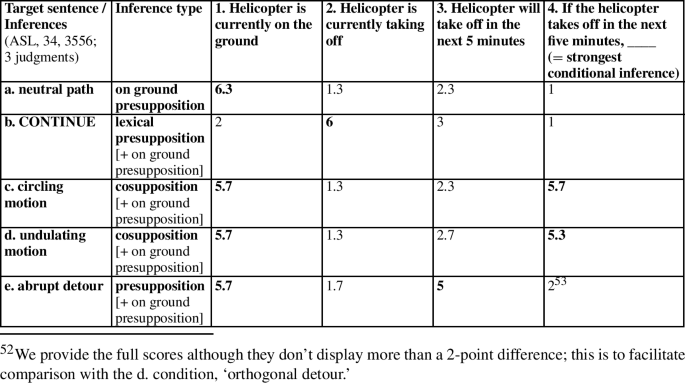

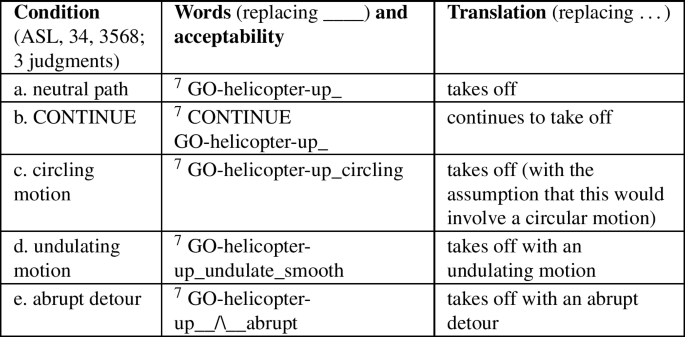

Under DOUBT and MAYBE, we obtain the expected pattern of projection: CONTINUE triggers a lexical presupposition (to the effect that the helicopter is currently taking off); all constructions except CONTINUE trigger a presupposition that the helicopter is currently on the ground (the presupposition triggered by CONTINUE is nearly incompatible with it: if the helicopter continues to take off, it is probably not on the ground anymore). The ‘circling motion’ and ‘undulating motion’ conditions trigger a cosupposition, to the effect that if the helicopter were to take off in the next five minutes, this would involve a circular/undulating motion. Finally, the ‘abrupt detour’ condition triggers a presupposition that the helicopter will in fact take off in the next five minutes.

For reasons we do not understand, the iconic cosuppositions involving a circling motion and an undulating motion are weakened under IF, as is the presupposition that the helicopter will in fact take off in the ‘abrupt detour’ condition. And under NONE (where we only have two judgments, and quite a bit of variation), only the presupposition triggered by CONTINUE and the cosuppositions involving a circular/undulating motion give rise to reasonably strong inferences.

-

(68)

DOUBT

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane.

WITHIN 5-MINUTES OUR COMPANY HELICOPTER DOUBT _____.

‘I doubt that within the next five minutes our company’s helicopter will ….’ (ASL, 34, 3562; 2 judgments)

-

(69)

MAYBE

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane. WITHIN 5-MINUTES OUR COMPANY HELICOPTER MAYBE _____.

‘Within the next five minutes, maybe our company’s helicopter will ….’ (ASL, 34, 3556; 3 judgments)

-

(70)

IF

Context: our company has one helicopter and one airplane.

WITHIN 5-MINUTES OUR COMPANY HELICOPTER IF _____, 2-CALL-1. ‘If within the next five minutes our company’s helicopter …, call me.’ (ASL, 34, 3568; 3 judgments)

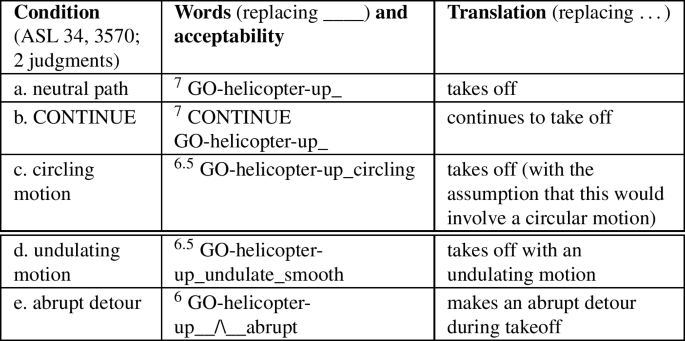

-

(71)

NONE

Context: our company has four helicopters and one airplane.

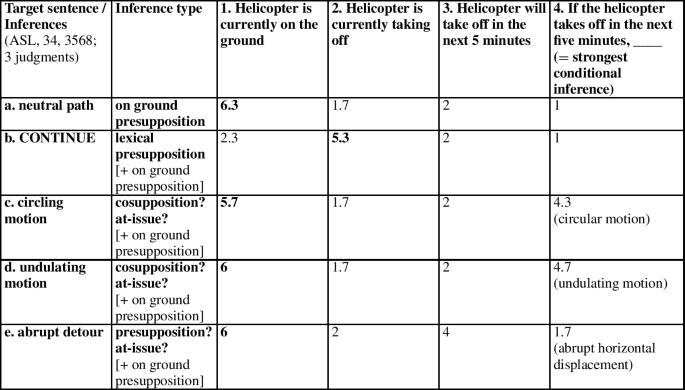

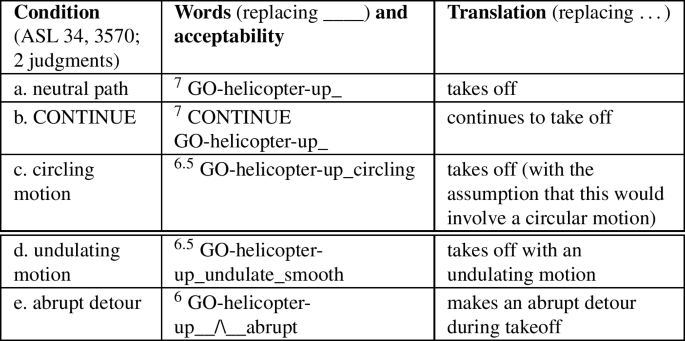

WITHIN 5-MINUTES OUR COMPANY 4 HELICOPTER NONE IX-arc _____. ‘Within the next five minutes, none of our company’s 4 helicopters will ….’ (ASL, 34, 3570; 2 judgments)

Appendix 2: The behavior under ellipsis of cosuppositions triggered by ASL classifier predicates

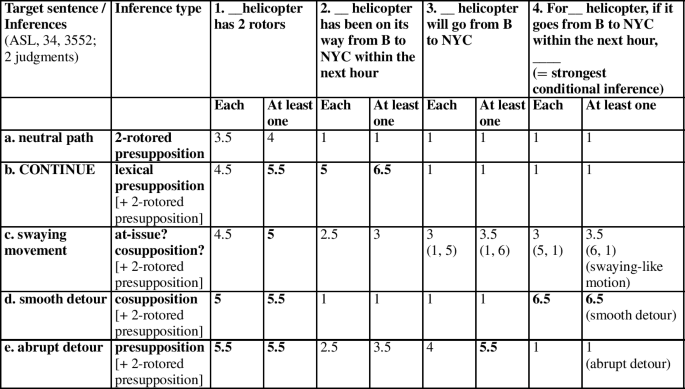

In this Appendix, we seek to determine whether our ASL consultant can ignore iconic cosuppositions of classifier predicates under ellipsis. According to the ‘revisionist hypothesis’ mentioned in Sect. 5, this should be possible. Our results do not bear this out: in an initial judgment task, our consultant disregarded cosuppositions under ellipsis; in two further judgment tasks, he didn’t. We discuss possible reasons for this.

In order to assess the behavior of cosuppositions under ellipsis, we focus on a version of our earlier paradigms involving embedding under MAYBE with an elided clause. Because the elided clause included an overt WILL but no VP, it is plausible that this is an instance of VP-ellipsis.

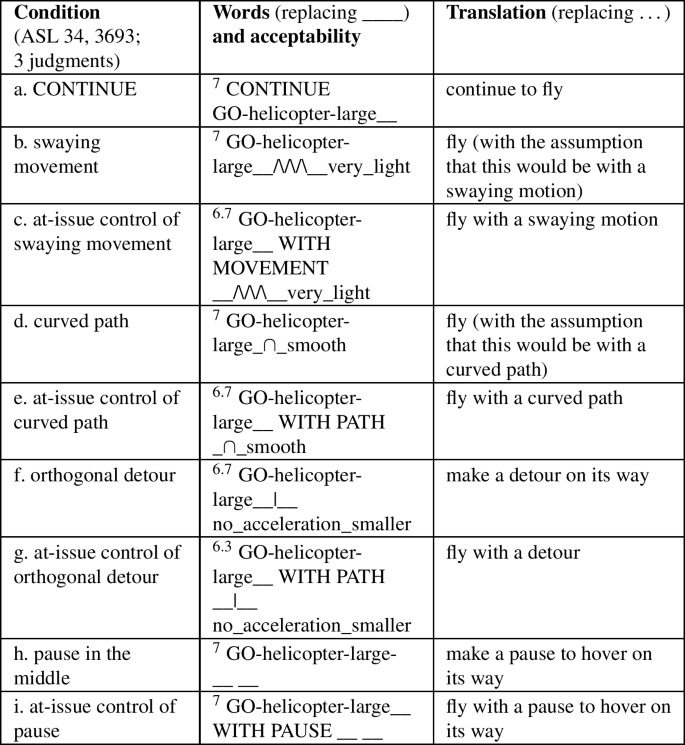

❑ Horizontal movement with ellipsis

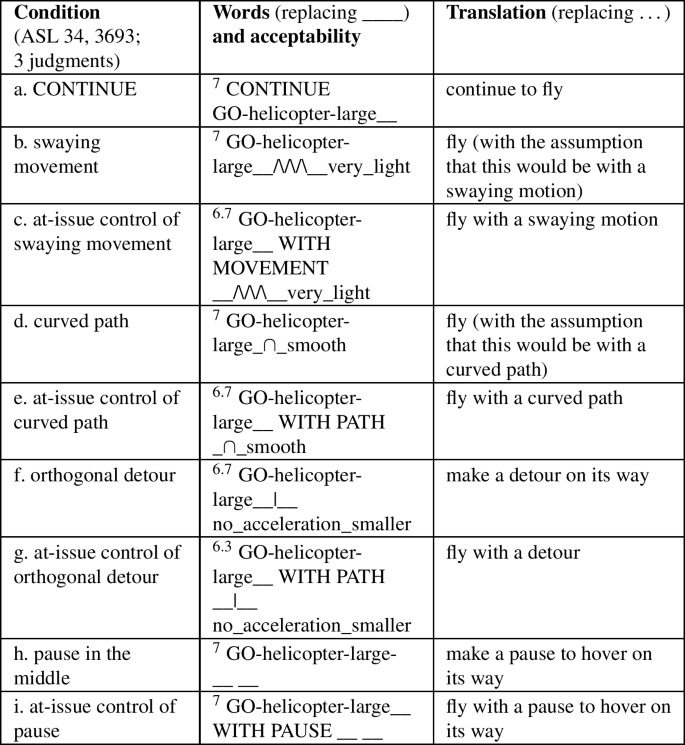

Our horizontal paradigm is illustrated in (72) and included a condition with CONTINUE in order to assess the behavior of a standard presupposition trigger.

-

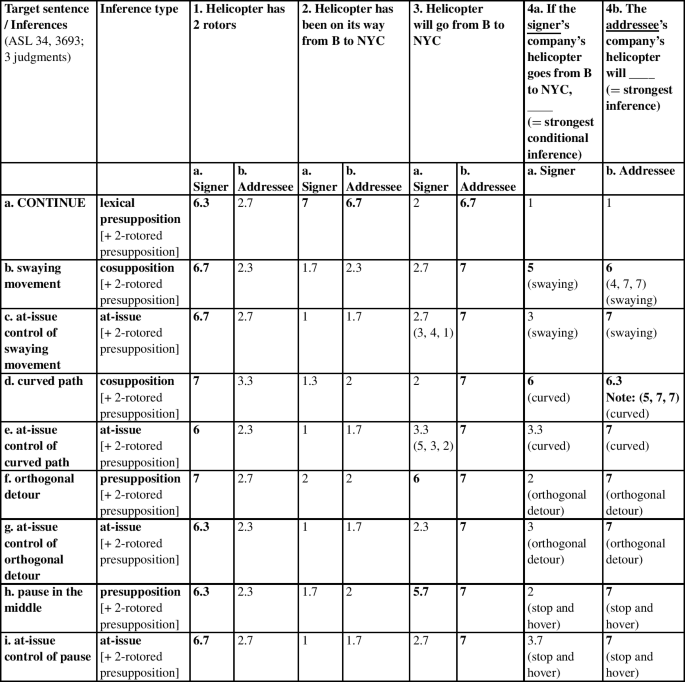

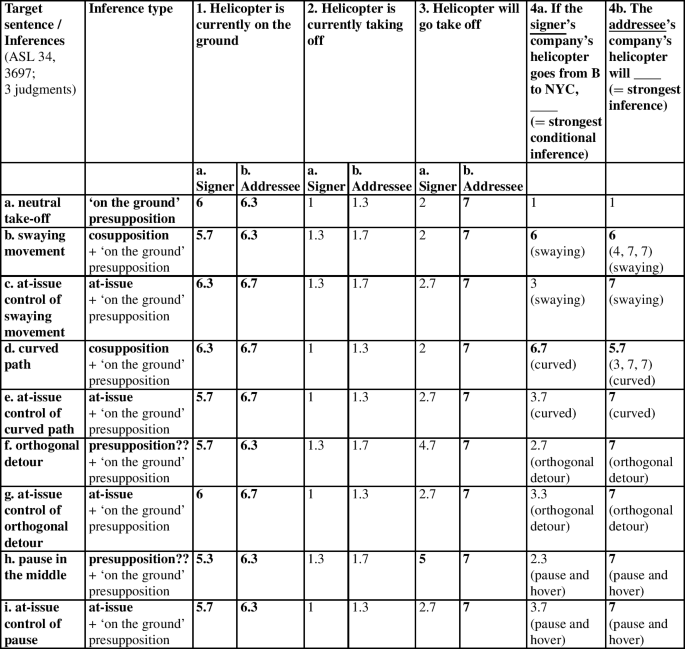

(72)

Context: the signer’s company has one helicopter and the addressee’s company also has one helicopter.

WITHIN 1-HOUR POSS-1 COMPANY BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKb MAYBE WILL a-____-b. POSS-2 COMPANY HELICOPTER DEFINITELY WILL.

‘Within the next hour, maybe my company’s big helicopter will … from Boston to New York. Your company’s helicopter definitely will.’ (ASL 34, 3693; 3 judgments)

As in our earlier paradigms, the strength of relevant inferences was assessed in a quantitative fashion by way of the questions in (73).

-

(73)

Quantitatively assessed inferences for the paradigm in (72)

Does the sentence suggest that any of the following is the case? (1 = no inference; 7 = strongest inference).

Answer separately for a. the signer’s company’s helicopter b. the addressee’s company’s helicopter.

Meaning 1: the helicopter has 2 rotors

Meaning 2: the helicopter has been on its way from Boston to NYC

Meaning 3: the helicopter will go from Boston to NYC within the next hour

Meaning 4a: About the signer’s company’s helicopter:

if the helicopter were to go from Boston to NYC within the next hour, it would

a. have a swaying-like motion

b. have a curved path

c. make an orthogonal detour

d. stop and hover on its way

(only pick the strongest inference among a, b, c, d)

Meaning 4b: About the addressee’s company’s helicopter:

within the next hour, the helicopter will

a. have a swaying-like motion

b. have a curved path

c. make an orthogonal detour

d. stop and hover on its way

(only pick the strongest inference among a, b, c, d)

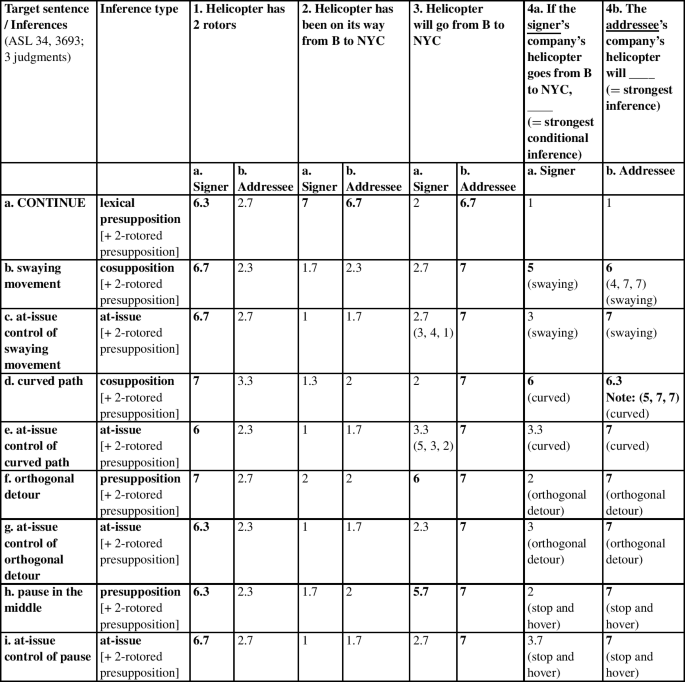

The consultant was asked to provide separate answers to questions about the signer’s company’s helicopter, and about the addressee’s company’s helicopter; this was crucial to assess differences between the antecedent clause and the elided clause. As a result, inferential questions systematically came in two versions (labeled a. and b. for the signer and addressee respectively). The antecedent was embedded under MAYBE so as to assess the difference between at-issue, presuppositional and cosuppositional inferences. Our goal was to see which of these inferences survived under ellipsis, and for this reason the elided clause was not embedded under MAYBE, in order to obtain sharper inferences, not involving modal reasoning.Footnote 52 This required a modulation of the fourth question: under MAYBE, it makes sense to test cosuppositional inferences in a conditional fashion (e.g. ‘if the company’s helicopter were to go from Boston to New York, would it have a swaying-like motion’), but without MAYBE, the relevant inference becomes unconditional (e.g. ‘the company’s helicopter will go from Boston to New York with a swaying-like motion’). This explains why there are two separate columns for question 4a and question 4b in the table in (74).

-

(74)

Horizontal, MAYBE, with ellipsis added: inferential results for the paradigm in (72)

Several conclusions can be drawn.

(i) The initial sentence with MAYBE (and without ellipsis) allows us to assess whether we managed to trigger the inferences we wanted. We did: the results strengthen the conclusions reached in the main text:

–In Column 4a, cosuppositions are obtained in the target sentences in the ‘swaying movement’ and ‘curved path’ conditions in b. and d. (= if the helicopter were to go from Boston to New York within the next hour, this would involve a swaying movement/a curved path), but not in the corresponding at-issue controls in c. and e.

–In Column 3a, presuppositions are obtained in the target sentences in the ‘orthogonal detour’ and ‘pause in the middle’ conditions in f. (= the helicopter will go from Boston to New York within the next hour), but not in the corresponding at-issue controls in g. and i.

(ii) The at-issue controls behave as expected, both under MAYBE and in the elided clause: they clearly must be copied under ellipsis.

(iii) The presupposition triggered by CONTINUE is as expected in the sentence with MAYBE. It is not preserved in the elided clause, and the reason might be quite simple: DEFINITELY WILL is missing a Verb Phrase, which can be resolved as CONTINUE GO-helicopter-large__ or just as GO-helicopter-large__. The inferential data suggest that the latter option is strongly preferred in this case.

(iv) Crucially, Column 4b suggests that cosuppositional inferences are inherited under ellipsis, since inferential scores are high for sentence b. and sentence d.

Thus the main conclusion is that the revisionist hypothesis according to which cosuppositions can be ignored under ellipsis is not at all confirmed. Two remarks must be made, however. First, judgments varied: the first judgment obtained (after right after the video was made) suggests that the cosupposition can to some extent be ignored. The latter two judgments disconfirm this. Second, nothing in the context really encouraged a reading without the cosupposition in the elided sentence. Thus it is conceivable that with a more inviting context the effect found in the first set of judgments could re-emerge—but we do not know this.

(v) By contrast, and perhaps surprisingly, the ‘2-rotored’ presupposition triggered by the two-handed nature of the classifier is easily ignored under ellipsis. We come back to this point at the end of this Appendix.

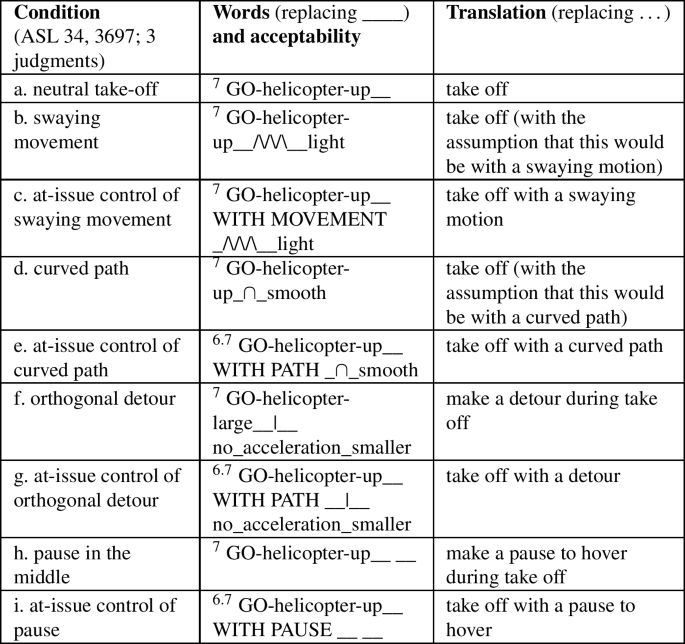

❑ Vertical movement with ellipsis

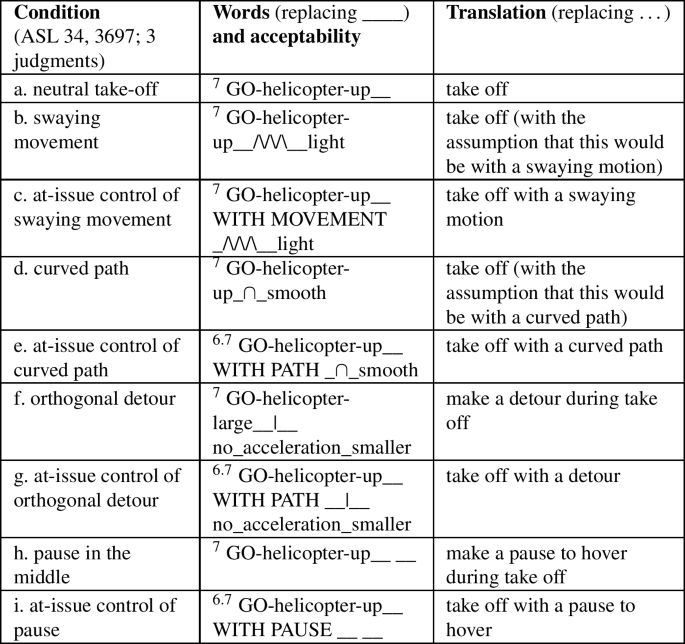

We turn to a paradigm with vertical movement depicting a helicopter take off, with the paradigm in (75).

-

(75)

Context: the signer’s company has one helicopter and the addressee’s company also has one helicopter.

WITHIN 5-MINUTES POSS-1 COMPANY HELICOPTER MAYBE WILL ___.

POSS-2 COMPANY HELICOPTER DEFINITELY WILL.

‘Within the next five minutes, maybe my company’s helicopter will …. Your company’s helicopter definitely will.’ (ASL 34, 3697; 3 judgments)

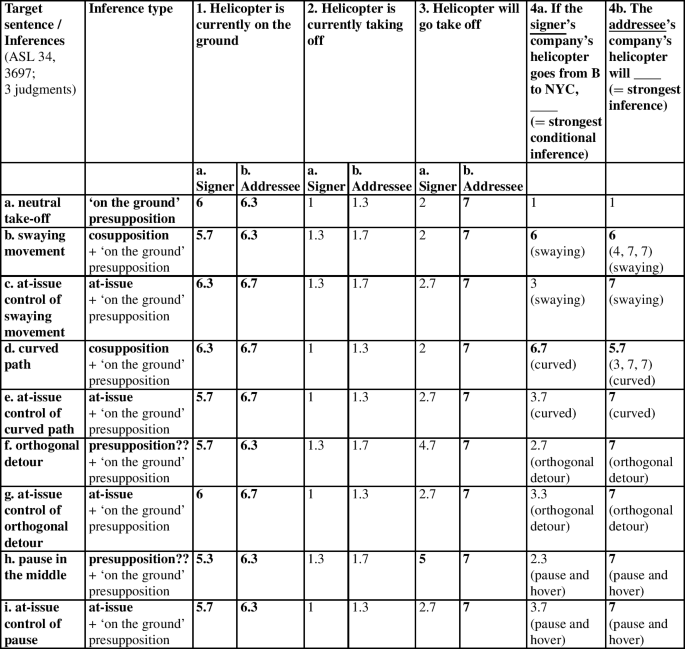

We provide judgments of inferential strength in (76). Because the helicopter predicate classifier is now a standard one, the ‘2-rotored’ inference from the preceding paradigm is replaced with one to the effect that the helicopter is currently on the ground (Column 1). By parallelism with the preceding paradigm, we preserved the inference that would have been triggered by CONTINUE (‘the helicopter continues to take off’), namely that the helicopter is currently taking off (Column 2); since this inference is not triggered by anything, endorsement should be at floor. Column 3 tests the existence of a presupposition to the effect that the helicopter will take off within the next 5 minutes. Finally, Columns 4a and 4b test two versions (depending on the presence or absence of MAYBE) of a cosuppositional inference to the effect that if the helicopter were to take off, it would have a swaying-like motion, or have a curved path, or make an orthogonal detour, or hover on its way (the consultant was to pick the strongest inference and assess its strength).

-

(76)

Vertical, MAYBE, with ellipsis added: inferential results for the paradigm in (75)

On the basis of these inferential judgments, a slightly weakened version of the main conclusions from the preceding paradigm can be drawn.

(i) The initial sentence with MAYBE (and without ellipsis) allows us to assess once again whether we managed to trigger the inferences we wanted. We did, although in slightly weaker from than in the horizontal paradigm (in (72)) for iconic presuppositions.

–In Column 4a, cosuppositions are obtained in the target sentences in the ‘swaying movement’ and ‘curved path’ conditions in b. and d. (= if the helicopter were to take off in the next five minutes, this would involve a swaying movement/a curved path), but not in the corresponding at-issue controls in c. and e.

–In Column 3a, weak presuppositions are obtained in the target sentences in the ‘orthogonal detour’ and ‘pause in the middle’ conditions in f. (= the helicopter will go from Boston to New York within the next hour, with endorsements rates of 4.7 and 5 respectively), but not in the corresponding at-issue controls in g. and i. (with endorsements rates of 2.7 and 2.7 respectively).

(ii) Here too, the at-issue controls behave as expected, both under MAYBE and in the elided clause: they clearly must be copied under ellipsis.

(iii) The presupposition that the first helicopter is currently on the ground is triggered as expected under MAYBE, and it is (rather unsurprisingly) preserved under ellipsis.

(iv) Crucially, Column 4b suggests that cosuppositional inferences are inherited under ellipsis, since inferential scores are high for sentence b. and sentence d. The same remarks hold as in the preceding horizontal paradigm: the revisionist hypothesis according to which cosuppositions can be ignored under ellipsis is not at all confirmed. But here too, judgments varied: the first judgment obtained suggests that the cosupposition can to some extent be ignored, the last two judgments disconfirm this. And one would need to determine whether a more inviting context could lead one to ignore the cosupposition under ellipsis.

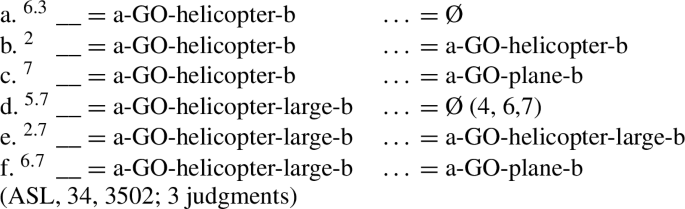

❑ The ‘2-rotored’ inference under ellipsis

We noted above the surprising fact that the ‘2-rotored’ inference can easily be disregarded under ellipsis. We do not know why this is: since it has the hallmarks of a presupposition rather than of a cosupposition, even the revisionist hypothesis (according to which cosuppositions can be ignored under ellipsis) couldn’t immediately explain this.

Still, it is important to test whether in other cases, the object-related information provided by the predicate classifier shape (as opposed to the path traced by the classifier) can be ignored under ellipsis. While judgments were not entirely stable, they suggest that ignorance of object shape under ellipsis is possible, as shown by the paradigm in (77).

-

(77)

Helicopter - plane

YESTERDAY POSS-1 COMPANY BIG HELICOPTER BOSTONa NEW-YORKa ____. POSS-1 COMPANY PLANE SAME ….

‘Yesterday my company’s big helicopter flew from Boston to New York. My company’s plane did too.’

The predicate classifier used in the antecedent clause corresponds to a normal helicopter (in (77)a-c) or to a 2-rotored helicopter (in (77)d-f). In all cases, the shape of this predicate classifier is inappropriate to represent the movement of an airplane, as is seen in the unelided controls (77)b and (77)e, which are very degraded: an airplane predicate classifier must be used instead, as seen in (77)c and (77)f. The crucial conditions are those with ellipsis in (77)a and (77)c: they are relatively acceptable. We leave it for future research to determine why this 2-rotored component can be disregarded in this way.Footnote 53

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schlenker, P. Iconic presuppositions. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 39, 215–289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09473-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09473-z

?

?

?

?

?

? [this] posture?

[this] posture?

to the effect that the relevant agent has hands on a wheel (irrespective of whether the agent turned the wheel or not). If x

to the effect that the relevant agent has hands on a wheel (irrespective of whether the agent turned the wheel or not). If x  has the content that x has their hands on a wheel, the disjunction (x

has the content that x has their hands on a wheel, the disjunction (x  or x

or x  ) will again yield the desired result.

) will again yield the desired result.

?

?