Abstract

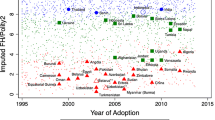

Under what conditions do states withdraw from intergovernmental organizations (IGOs)? Recent events such as Brexit, the US withdrawal from UNESCO, and US threats to withdraw from NAFTA, NATO, and the World Trade Organization have triggered widespread concern because they appear to signify a backlash against international organizations. Some observers attribute this recent surge to increasing nationalism. But does this explanation hold up as a more general explanation for IGO withdrawals across time and space? Despite many studies of why states join IGOs, we know surprisingly little about when and why states exit IGOs. We use research on IGO accession to derive potential explanations for IGO withdrawal related to domestic politics, IGO characteristics, and geo-politics. We quantitatively test these potential explanations for withdrawal using an original dataset of 493 IGOs since 1945, documenting about 200 cases of withdrawal. We find that nationalism is not the key driver of IGO withdrawals in the past. Instead, we show that geo-political factors – such as preference divergence and contagion – are the main factors linked to IGO withdrawals, followed by democracy levels in the country and organization. These findings have important implications for research on the vitality of international organizations, compliance, and the liberal world order.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Abbott and Snidal 1998.

Hirschman 1970.

See https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/u-s-and-israel-officially-withdraw-from-unesco. Accessed March 12, 2019.

See https://dailycoffeenews.com/2018/04/03/the-united-states-is-withdrawing-from-the-international-coffee-agreement/. Accessed March 12, 2019.

If one looks beyond withdrawals from formal IGOs, the pattern of recent US withdrawals looks even starker, including withdrawals from treaties (that are not IGOs because they do not include Secretariats), informal agreements, and emanations such as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (Iran Nuclear Deal), Paris Climate Accord, UN Human Rights Council, and the Transpacific Partnership.

Pevehouse et al. 2004.

Snyder 2019: 54.

Foa 2016.

Holsti 1992.

Leeds and Savun 2007.

Downs et al. 1996.

See, for example, Pevehouse 2002.

Bearce and Bondanella 2007.

Pevehouse et al. 2019. In the conclusion we suggest ways that this IGO definition might matter, and possibilities for future research to examine exits from other forms of international cooperation.

Authors’ calculation based on original data.

There is no data source to cover a sufficient number of COW IGOs to test this idea across a wide range of IOs. DESTA contains data on treaty flexibility provisions but these are mostly bilateral treaties, not IGOs. Koremenos (2016) contains just a sample and small fraction of our set of IGOs.

Aust 2013.

Rosendorff and Milner 2001.

McCall Smith 2000.

Hirschman’s (1970) Exit, Voice, and Loyalty also provides an informative framework for understanding the various choices states face.

See Gray 2018 on “zombie” organizations.

Membership withdrawal might be considered ‘the final straw.’ This paper does not address instances when a state engages in less significant departures such as no longer participating in the IGO’s work or meetings, withdrawing from IGO projects or conferences, withholding IGO contributions, or lowering the diplomatic rank of meeting attendees (see Online Appendix for examples). Likewise, withdrawal from treaties unrelated to IGOs are not included in this study (see Penney 2002).

Chayes and Chayes (1991: 316) also remind us that we should not expect withdrawals often.

Author’s interview with US-based IWC expert, July 2018.

See https://www.ecotourism.org.au/news/australias-withdrawal-from-the-uns-world-tourism-organisation/. Accessed 17 October 2018.

Most states still pay their IGO dues during notice and wait periods before they have officially withdrawn. This has important implications for international cooperation and compliance.

Beigbeder 1979.

Ibid.

Shukla 2018.

Shukla 2018

See Farrell and Newman 2017

See https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/18/england-eu-referendum-brexit. Accessed 17 October 2018.

Walt (2016).

2016 Gallup survey; 2016 poll by the Pew Research Center.

See online appendix for coding details.

See online appendix for examples of cases in each of the category and for coding criteria.

http://www.voanews.com/content/gambia-withdraws-from-the-commonwealth/1761959.html. Accessed 22 May 2018.

von Borzyskowski and Vabulas forthcoming.

While this is a productive way forward, we recognize potential limitations of leaning heavily on accession theories: some studies find that alliance termination contrasts with formation (Leeds and Savun 2007; Orbell et al. 1984) and European disintegration is not simply “integration in reverse.” See Jones 2018; Schneider 2017.

Putnam 1988.

Kaoutzanis et al. 2016.

Milner and Tingley 2011.

Predictions are not clear with regard to the right-left dimension of government change. Isolationist parties tend to be right-leaning in the US and Europe; left-leaning in Latin America; and of unclear leanings in Africa and Asia.

Milner and Tingley 2011.

See Copelovitch and Pevehouse, this Issue.

See Haftel and Thompson (2018) on a similar logic explaining that states renegotiate treaties when they are not functioning as they had hoped.

Keohane 1984.

Abbott and Snidal 1998.

Hirschman 1970.

Leeds and Savun 2007.

Pevehouse 2002.

Boehmer et al. 2004; Karreth and Tir 2012.

See Haftendorn et al. (1999) on a similar logic with regard to the institutionalization of alliances. On the other hand, states may be more likely to withdraw from highly institutionalized IGOs that have established too much independent agency or established a ‘runaway bureaucracy’ that stands apart from states’ original intent.

See Davis and Wilf (2017) on geopolitical preferences affecting economic organization membership.

Downs et al. 1996; Jupille et al. 2013; Gray et al. Forthcoming.

Simmons 2000.

Gruber 2000.

Olson 1965.

Ikenberry 2000.

EU disintegration literature have also noted a potential contagion effect. See Walter 2018.

Pacheco 2012.

The availability of two domestic politics variables limits the timeframe in the domestic politics model to 1975–2014.

Pevehouse et al. 2019.

Donno et al. 2015; Poast and Urpelainen 2013.

Pevehouse et al. 2019.

Since the data cover 265 of the 493 organizations, which lowers the sample size of IO-state-years by about a quarter, we also run robustness tests without this variable.

Lall (2017) provides data for a total of 53 international bodies (organizations, programs, and funds); 18 of them are IGOs.

See for example State Dept 1997: 6.

von Borzyskowski 2019.

We scale the CINC score change (multiplying it by 100) to keep coefficients on a similar scale, which eases readability of coefficients.

We also account for economic power with variables for GDP growth. See Appendix Table A3.

Barnett and Finnemore 1999.

King and Zeng 2001.

Charnovitz 2017.

This is also based on DPI data and its nationalism and vote share variables for the executive, government, and opposition. We replicated Table 1 model 1; replicating model 4 yields quite similar results.

We do not include this variable in the main analysis because it is only available since 1960, which restricts the sample size and temporal coverage across models.

Iacus et al. 2012. We use five cutpoints for polity and growth, and one cutpoint for government orientation change. The balanced dataset has a multivariate L1 distance of 0.65, far from perfect imbalance of 1. Using the generated CEM weights, the p value of the bivariate rare events logit estimate is 0.8 and of the multivariate rare events logit (including controls to further improve balance) is 0.7.

Gray 2013.

C.f. Imber 1989.

Details provided in the Online Appendix.

We source human rights data from Gibney et al. 2013; polity2 data from Marshall et al. 2010; coup data from Marshall and Marshall 2012; government harassment of opposition from Hyde and Marinov 2011, and data on unacceptable election quality or major election problems from Kelley 2010, 4–5. A 2+ point reduction in human rights or Polity2 indexes is large enough to eliminate measurement errors (which could occur as a result of one- point fluctuations that might reasonably occur on a year-to-year basis) and small enough to capture real-world events (where a two-point drop has been enough to trigger discussions about institutional sanctions). The 2+ point reduction also means that we are agnostic about where the country is on the democracy scale.

Vabulas and Snidal 2013.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why states act through formal international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32.

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization, 54(3), 421–456.

Aust, A. (2013). Modern treaty law and practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, M., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456.

Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (1999). The politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. International Organization, 53(4), 699–732.

Bearce, D. H., & Bondanella, S. (2007). Intergovernmental organizations, socialization, and member-state interest convergence. International Organization, 61, 703–733.

Beck, N., Katz, J. N., & Tucker, R. (1998). Taking time seriously: Time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 1260–1288.

Beigbeder, Y. (1979). The United States’ withdrawal from the international labor organization. Industrial Relations, 34(2), 223–240.

Blyth, M. (2017). Global Trumpism: Why Trump’s victory was 30 years in the making and why it Won’t stop Here. Foreign Affairs anthology.

Boehmer, C., Gartzke, E., & Nordstrom, T. (2004). Do intergovernmental organizations promote peace? World Politics, 57, 1–38.

Carr, E. H. (1964). The twenty years crisis, 1919–1939: An introduction to the study of international relations (pp. 208–223). New York: Harper and Row.

Carter, D., & Signorino, C. (2010). Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data. Political Analysis, 18(3), 271–292.

Charnovitz, S. (2017). Why the international exhibitions bureau should choose Minneapolis for global expo 2023. GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works.

Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. (1991). Compliance without enforcement: State behavior under regulatory treaties. Negotiation Journal, 7(3), 311–330.

Cogan, J. K., Hurd, I., & Johnstone, I. (Eds.) 92016). The Oxford handbook of international organizations. Oxford University Press.

Davis, C. L., & Wilf, M. (2017). Joining the Club? Accession to the GATT/WTO. The Journal of Politics, 79, 964–978.

Donno, D. (2010). Who is punished? Regional intergovernmental organizations and the enforcement of democratic norms. International Organization, 64(4), 593–625.

Donno, D., Metzger, S. K., & Russett, B. (2015). Screening out risk: IGO s, member state selection, and interstate conflict, 1951–2000. International Studies Quarterly, 59(2), 251–263.

Downs, G. W., Rocke, D. M., & Barsoom, P. N. (1996). Is the good news about compliance good news about cooperation? International Organization, 50(3), 379–406.

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2017). BREXIT, voice and loyalty: Rethinking electoral politics in an age of interdependence. Review of International Political Economy, 24(2), 232–247.

Fearon, J. D. (1997). Signaling foreign policy interests: Tying hands versus sinking costs. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 68–90.

Foa, S. (2016). Its the globalization, stupid. Foreign Policy, Dec 6 2016.

Fukuyama, F. (2016). US against the world? Trump’s America and the new global order’, Financial Times, 11 November 2016.

Gaubatz, K. T. (1996). Democratic states and commitment in international relations. International Organization, 50(1), 109–139.

Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R. and Haschke, P. (2013). Political terror scale 1976-2012. Available at http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/ Accessed 3 July 2013.

Gilpin, Robert. 1983. War and change in world politics. Cambridge University Press.

Gray, J. (2013). The company states keep: International economic organizations and investor perceptions. Cambridge University Press.

Gray, J. (2018). Life, death, or zombie? The vitality of international organizations. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 1–13.

Gray, J., Lindstadt, R. and Slapin, J. B. (Forthcoming). The dynamics of enlargement in international organizations. International Interactions.

Greig, M., Enterline, A. (2017). COW National Material Capabilities (NMC) data documentation, Version 5.

Gruber, L. (2000). Ruling the world: Power politics and the rise of supranational institutions. Princeton University Press.

Haas, R. (2018). Liberal world order, R.I.P. Project Syndicate, March 21 2018. Available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/end-of-liberal-world-order-by-richard-n%2D%2Dhaass-2018-03?barrier=accesspaylog. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Haftel, Y., & Thompson, A. (2018). When do states renegotiate investment agreements? The impact of arbitration. The Review of International Organizations, 13(1), 25–48.

Haftendorn, H., Keohane, R. O., & Wallander, C. A. (1999). Imperfect unions: Security institutions over time and space. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hawkins, K., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). The ideational approach to populism. Latin America American Research Review, 52(4), 513–528.

Helfer, L. R. (2005). Exiting treaties. Virginia Law Review, 91, 1579.

Helfer, L. R. (2006). Not fully committed-reservations, risk, and treaty design. Yale Journal of International Law, 31, 367.

Hill, J. A. (1982). European economic community: The right of member state withdrawal, the. Ga. Journal of International and Comparative Law, 12, 335.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

Hobolt, S., and de Vries, C. (2016). Public Support for European Integration. Annual Review of Political Science 19. Annual Reviews: 413–32.

Holsti, O. R. (1992). Public opinion and foreign policy: Challenges to the almond-Lippmann consensus. International Studies Quarterly, 36(4), 439–466.

Houle, C., & Kenny, P. (2018). The political and economic consequences of populist rule. Government and Opposition., 53, 256–287.

Huber, R., & Ruth, S. (2017). Mind the gap! Populism, participation and representation in Europe. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 462–484.

Huber, R., & Schimpf, C. (2016). A drunken guest in Europe? The influence of populist radical right parties on democratic quality. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 10, 103–129.

Hyde, S. D., & Marinov, N. (2011). Codebook for National Elections across Democracy and autocracy (NELDA). New Haven: Yale University.

Iacus, S., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20(1), 1–24.

Ikenberry, G. J. (2000). After victory: Institutions, strategic restraint, and the rebuilding of order after major wars. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ikenberry, J. (2018). The end of liberal international order? International Affairs, 94(1), 7–23.

Imber, M. F. (1989). The USA, ILO, UNESCO and IAEA: Politicization and withdrawal in the specialized agencies. Springer.

Johnson, T. (2014). Organizational progeny: Why governments are losing control over the proliferating structures of global governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jones, E. (2018). Towards a theory of disintegration. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (3). Routledge: 440–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1411381.

Jupille, J., Mattli, W., & Snidal, D. (2013). Institutional choice and global commerce. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kagan, R. (2017). The twilight of the liberal world order. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-twilight-of-the-liberal-world-order/. Accessed 30 March 2018.

Kaoutzanis, C., Poast, P., & Urpelainen, J. (2016). Not letting ‘bad apples’ spoil the bunch: Democratization and strict international organization accession rules. Review of International Organization, 11, 399–418.

Karreth, J., & Tir, J. (2013). International institutions and civil war prevention. Journal of Politics, 75(1), 96–109.

Keohane, R. (1984). After hegemony: Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton University Press.

Kertzer, J. D., & Brutger, R. (2016). Decomposing audience costs: Bringing the audience back into audience cost theory. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 234–249.

King, G., & Zeng, L. (2001). Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Analysis, 9(2), 137–163.

Koremenos, B. (2016). The continent of international law: Explaining agreement design. Cambridge University Press.

Koremenos, B., & Nau, A. (2010). Exit, no exit. Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law, 21, 81.

Koremenos, B., Lipson, C., & Snidal, D. (2001). The rational design of international institutions. International Organization, 55(4), 761–799.

Kucik, J., & Reinhardt, E. (2008). Does flexibility promote cooperation? An application to the global trade regime. International Organization, 62(3), 477–505.

Kuo, J., & Naoi, M. (2015). Individual Attitudes. In L. Martin (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Political Economy of International Trade. Oxford: Oxford.

Lall, R. (2017). Beyond institutional design: Explaining the performance of international organizations. International Organization, 71, 245–280.

Leeds, B. A. (1999). Domestic political institutions, credible commitments, and international cooperation. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 979–1002.

Leeds, B. A., & Savun, B. (2007). Terminating alliances: Why do states abrogate agreements? The Journal of Politics, 69(4), 1118–1132.

Lipson, C. (2003). Reliable partners: How democracies have made a separate peace. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mansfield, E., & Pevehouse, J. (2006). Democratization and international organizations. International Organization, 60, 137–167.

Maoz, Z., Johnson, P., Kaplan, J., Ogunkoya, F., and Shreve, A. (2018). The dyadic militarized interstate disputes (MIDs) dataset version 3.0: Logic, characteristics, and comparisons to alternative datasets. Journal of Conflict Resolution.

Marshall, M. and Marshall, D. (2017). Coup d’état events 1946–2016. Center for systematic peace.

Marshall, M.G., Jaggers, K., Gurr, T. (2010). Polity IV project: Characteristics and transitions, 1800–2009. Dataset Users’ Manual. Center for Systemic Peace.

Martin, L. L. (2000). Democratic commitments: Legislatures and international cooperation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McCall Smith, J. (2000). The politics of dispute settlement design: Explaining legalism in regional trade pacts. International Organization 137-180.

McGillivray, F., & Smith, A. (2000). Trust and cooperation through agent-specific punishments. International Organization, 54(4), 809–824.

Milner, H. V., & Tingley, D. H. (2011). Who supports global economic engagement? The sources of preferences in American foreign economic policy. International Organization, 65(1), 37–68.

Morgan, T. C., & Campbell, S. H. (1991). Domestic structure, decisional constraints, and war: So why Kant democracies fight? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 35(2), 187–211.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Orbell, J. M., Schwartz-Shea, P., & Simmons, R. T. (1984). Do cooperators exit more readily than defectors? American Political Science Review, 78(1), 147–162.

Organski, A. F. K. (1964). World politics. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Pacheco, J. (2012). The social contagion model: Exploring the role of public opinion on the diffusion of antismoking legislation across the American states. The Journal of Politics 74 (1). Cambridge University Press New York, USA: 187–202.

Pelc, K. J. (2009). Seeking escape: The use of escape clauses in international trade agreements. International Studies Quarterly, 53(2), 349–368.

Penney, E. K. (2002). Is that legal?: The United States' unilateral withdrawal from the anti-ballistic missile treaty. Catholic University Law Review, 51, 1287–1393.

Pevehouse, J. (2002). With a little help from my friends? Regional organizations and the consolidation of democracy. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 611–626.

Pevehouse, J., and von Borzyskowski, I. (2016). International organizations in world politics. In The Oxford Handbook of International Organizations, edited by Jacob Katz Cogan, Ian Hurd and Ian Johnstone, 3-32.

Pevehouse, J., Nordstrom, T., & Warnke, K. (2004). The correlates of war 2 international governmental organizations data version 2.0. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 21(2), 101–119.

Pevehouse, J., Nordstrom, T., McManus, R., Jamison, A. (2019). Tracking organizations in the world: The correlates of war IGO data, version 3.0. Working paper.

Putnam, R. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization, 42(3), 427–460.

Rosendorff, P., & Milner, H. (2001). The optimal Design of International Trade Institutions: Uncertainty and escape. International Organization, 55(4), 829–857.

Schneider, C. (2017). Political economy of regional integration. Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1). Annual Reviews.

Shukla, S. (2018). International relations on the rise of nationalism: Institutions and global governance. McGill Journal of Political Studies. https://mjps.ssmu.ca/2018/02/09/international-relations-on-the-rise-of-nationalism-institutions-and-global-governance/. Accessed 1 Apr 2018.

Simmons, B. A. (2000). International law and state behavior: Commitment and compliance in international monetary affairs. American Political Science Review, 94(04), 819–835.

Simmons, B. A., & Danner, A. (2010). Credible commitments and the international criminal court. International Organization, 64(2), 225–256.

Singer, J. D., Bremer, S., & Stuckey, J. (1972). Capability distribution, uncertainty, and major power war, 1820-1965. In B. Russett (Ed.), Peace, war, and numbers (pp. 19–48). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Smith, A. (1995). Alliance formation and war. International Studies Quarterly, 39(4), 405–425.

Smith, A. (1998). Extended deterrence and Alliance formation. International Interactions, 24(4), 315–343.

Snyder, J. (2019). The broken bargain. Foreign Affairs, March–April, 54–60.

State Dept. (1997). US Participation in Special Purpose International Organizations. US GAO, NSIAD 97-35.

Stone, R. (2011). Controlling institutions: International organizations and the global economy. Cambridge University Press.

Vabulas, F., & Snidal, D. (2013). Organization without delegation: Informal intergovernmental organizations (IIGOs) and the spectrum of intergovernmental arrangements. The Review of International Organizations, 8(2), 193–220.

von Borzyskowski, I. (2019). The credibility challenge: How democracy aid influences election violence. Cornell University Press.

von Borzyskowski, I., and Vabulas F. (Forthcoming). Credible Commitments? Explaining IGO Suspensions to Sanction Political Backsliding. International Studies Quarterly.

Wagner, R. H. (2000). Bargaining and war. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 469–484.

Walter, B. F. (2009). Bargaining failures and civil war. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 243–261.

Walter, S. (2018). The mass politics of international disintegration. Paper prepared for presentation at the International Relations research seminar, Harvard University, 8 March 2018.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xinyuan Dai, Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser, Christian Rau, Henning Schmidtke, Duncan Snidal, Alexander Thompson, Svanhildur Thorvaldsdottir, Alexander Tokhi, Stefanie Walter, as well as conference participants at MPSA, PEIO, the Global Governance group at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin (WZB), and three anonymous reviewers for useful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. We also thank Richard Saunders for excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The dataset in this RIO article on membership withdrawals and the dataset in our ISQ article on membership suspensions (2019) are also companion datasets to the COW IGO data (Pevehouse et al. 2019). On the COW website (http://correlatesofwar.org/data-sets), we provide code files for R and Stata, which can be run to adjust the COW dataset for IGO membership exits and interruptions. If you use the data and/or correction code, please reference both the RIO and ISQ articles.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

von Borzyskowski, I., Vabulas, F. Hello, goodbye: When do states withdraw from international organizations?. Rev Int Organ 14, 335–366 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09352-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09352-2