Abstract

In the coming century, average temperatures are predicted to increase by 2.5 to ten degrees Fahrenheit as a result of climate change. Yet citizens around the world vary in their perceptions of how serious the threat of rising temperatures is. I argue that variation in the perceived seriousness of climate change reflects the degree to which individuals internalize the welfare of others in society besides themselves. I describe and two models of “other-regarding” preferences - social welfare maximization and inequity aversion - and test their predictions using data from the World Values Survey. I employ genetic matching and a difference-in-difference design in order to mitigate potential endogeneity. I also explore behavioral implications of the theory using original data on climate change-related web searches. The empirical tests support the argument: individuals who exhibit high levels of other-regarding preferences are more likely to express serious concern - and seek out new information - about global warming.

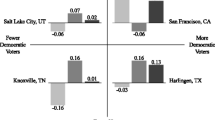

Marginal effects of social preference variables corresponding to Models 3 and 4 in the lower panel of Table 3. Estimated using the mfx package in R. Dependent variable is expressed concern about global warming. Measures of social welfare maximization and inequity aversion constructed via principal components analysis and dichotomized according to 90th percentile. Estimates for Female, Education, Income, Age, and GDP per Capita omitted due to space constraints

Relative intensity of climate change-related Google searches in 2015. Darker shades indicate greater relative intensity

Relative intensity of climate change-related Google searches, 2005-2015. Each grey line corresponds to an individual country, with region averages depicted according to the legend

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See https://climate.nasa.gov/effects/. Recent studies suggest that Pacific Island nations may already be experiencing significant shoreline recession (Albert et al. 2016).

According to the World Values Survey, Wave 5.

This work is similar in spirit to Bechtel et al. (2017) which demonstrates that altruistic individuals are on average more supportive of international climate cooperation. The present contribution builds on this existing work in three ways. First, it explores the microfoundations of altruism by developing two alternative models of other-regarding preferences. Second, it provides evidence of a direct relationship between altruism and the salience of climate change as a political issue in contrast with willingness-to-pay in a global public goods setting. Finally, the current work tests these arguments cross-nationally providing evidence that such explanations have broad external validity.

In the Appendix I also present the results of fixed effects specifications which accounts for unobservable, yet invariant unit-specific confounders. The fixed effects specification provides another means of addressing potential omitted variables bias though other forms of endogeneity (reverse causality) may remain.

See also Rathbun et al. (2016) which applies similar insights to foreign policy attitudes.

See also Camerer and Fehr (2002)

An enduring concern with such experiments is that they may not correspond to actual behaviors outside the laboratory. Benz and Meier (2006) provide evidence that altruistic behavior in a laboratory setting is correlated with altruistic behavior in the field. The authors collect data on student charitable donations prior to conducting a lab experiment and then match participants’ behavior in the lab setting with their donation history. The study finds that altruism in the lab-setting correlates at between 0.25 and 0.4 with behavior outside of the lab.

As an early example, the 2007/2008 Human Development Report notes that if unabated, climate change could be “ apocalyptic” for some of the poorest people in the world (Watkins 2007).

Note that my use of scientific uncertainty refers to uncertainty at the individual level regarding the existing scientific consensus, not necessarily the certainty of that consensus itself.

While the attribution of specific events may lead egoistic individuals to update the relative likelihood they themselves will be affects, based on the geographic location of prior events, as these events can only be attributed to climate change ex post some level of distributional uncertainty will always persist.

Two additional studies highlight the role of education and post-materialism (Kvaloy et al. 2012) and education and local temperature change (Lee et al. 2015) respectively. An older literature also provides thorough descriptive evidence of climate change awareness and preferences in cross-national context. For examples see Nisbet and Myers (2007), Lorenzoni and Pidgeon (2006), and Brechin and Bhandari (2011) and Leiserowitz et al. (2007).

Alternatively excluding those respondents who reply that climate change is “not very serious” or “not serious at all” does not change the results.

The selected items are depicted in Table 1 of the Supplementary Materials.

The selected items are depicted in Table 2 of the Supplementary Materials.

Using the prcomp package in R. In practice this leads to the elimination of only one variable from the two sets of items. The eliminated variable is V115 from the set of inequity aversion items.

Table 3 and Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Materials provide an overview of the construction of the Collectivism measure.

For completeness I also conduct additional robustness checks which show that employing the second principle component as an alternative measure does in most cases not substantively alter the results.

I reverse code the measure so that higher values indicate lower identification with risk taking behavior, that is risk aversion.

While political identity can be measured in many ways existing research provides strong justification for employing the self-positioning scale as an appropriate proxy. As Egan and Mullin (2017) note, “Partisan divisions on the issue [of climate change] are not limited to the United States: A meta-analysis of 25 polls and 171 studies in 156 countries showed that identification with conservative parties and ideology strongly and consistently predicted climate change skepticism across political settings.” Robustness exercises described below consider alternative measures of political identity.

Measuring exposure to extreme environmental events using the total number of deaths from natural disasters or a simple count of natural disasters occuring in the year prior to data collection does not alter the results.

While it would be preferable to have individual level measures of economic impact (industry of employment for example), no such data was not collected by the World Values Survey.

Controlling instead for the proportion of a nation’s border’s made up of coastline yields similar results.

GDP per capita obtained from the World Bank.

In other words, the goal of matching is to achieve balance across high- and low-social preference groups in terms of the multivariate distribution of potentially related observables. In the results presented below I emphasize key independent variables and covariates. Full results for all parameter estimates below can be found in Table 5 of the Supplementary Materials.

Among the included covariates, right-wing political views and evangelicalism are negatively correlated with concern as predicted by existing literature. Similarly post-materialism exhibits a positive and statistically significant association across all models. Both the indicator for island nations and the per capita carbon emissions variables are signed as expected and - in the case of the former - statistically significant across the board.

See Table 6 of the Supplementary Materials.

See Table 7 of the Supplementary Materials.

See Table 8 of the Supplementary Materials. Results for the matched sample analyses available upon request.

See Table 9 in the Supplementary Materials.

Note that inclusion of these potentially post-treatment variables can result in severely biased coefficient estimates. Genetic matching implemented via the MatchIt package in R.

Additional diagnostics of the matching procedures are included in Figs. 2 and 3 of the Supplementary Materials. These figures depict the univariate distributions for treated versus control units for each matched covariate. Again, the distributions are very similar indicating that the matched samples are well-balanced across treatment conditions.

Full covariate results are included in Tables 10 and 11 of the Supplementary Materials. There I also include additional results obtained by creating matched samples based on a threshold equivalent to the 75th rather than the 90th percentile of each social preference variable. Re-estimating the models depicted in Table 3 using these alternative samples generates substantively similar results. See Tables 12 and 13 of the Supplementary Materials.

Robustness results for the matched samples available on request.

See Tables 14–16 in the Supplementary Materials.

See Table 17 of the Supplementary Materials.

This allows the data to be interpreted as proportions of total search volume for a particular time and location enabling comparison across settings with different numbers of Internet users.

These are the four years following administration of the World Values Survey.

In total I collect data for English and an additional 27 foreign languages including Arabic, Bulgarian, Dutch, Finish, French, German, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Norwegian, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Simplified Chinese, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Traditional Chinese, Turkish, Ukrainian, and Vietnamese. See Appendix for additional details on construction of the dataset.

I exclude the measure of per capita emissions intensity as limitations in its availability dramatically reduce an already small samples size. As the measure has greater availability during the 2005-2009 window, as a robustness check I re-estimate the models presented here on that earlier sample including per capita emissions as a covariate. The results remain unchanged though estimation on this earlier window, which is contemporaneous with the WVS itself, may introduce potential for post-treatment bias. Alternatively, including country fixed effects does not alter the results. Results available upon request.

For a recent example see Gelman (2009) on how reliance on ecological inference has led to widespread misperceptions of red versus blue state voting patterns in the United States.

References

Aaron, M., & McCright, A. (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the american public. Population and Environment, 32(1), 66–87.

Albert, S., Leon, J.X., Grinham, A.R., Church, J.A., Gibbes, B.R., Woodroffe, C.D. (2016). Interactions between sea-level rise and wave exposure on reef island dynamics in the solomon islands. Environmental Research Letters, 11(5), 054011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/054011.

Andreoni, J., & Miller, J. (2002). Giving according to garp: An experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism. Econometrica, 70(2), 737–753.

Arbuckle, M.B., & Konisky, D.M. (2015). The role of religion in environmental attitudes. Social Science Quarterly, 96(5), 1244–1263.

Burcu Bayram, A. (2016). Values and Prosocial behavior in the global context Why values predict public support for foreign development assistance to developing countries. Journal of Human Values, 22(2), 93–106.

Bechtel, M.M., Genovese, F., Scheve, K.F. (2017). interests, norms, and support for the provision of global public goods: The case of climate co-operation. British Journal of Political Science.

Benz, M., & Meier, S. (2006). Do people behave in experiments as in the field? - evidence from donations. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.756372.

Borick, C.P., & Rabe, B.G. (2014). Weather or not? examining the impact of meteorological conditions on public opinion regarding global warming. Weather, Climate, and Society, 6(3), 413–424. 10.1175/wcas-d-13-00042.1.

Brechin, S.R., & Bhandari, M. (2011). Perceptions of climate change worldwide. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2(6), 871–885.

Brody, S. D., Zahran, S., Vedlitz, A., Grover, H. (2008). Examining the relationship between physical vulnerability and public perceptions of global climate change in the united states. Environment and behavior, 40(1), 72–95.

Brügger, A., Dessai, S., Devine-Wright, P., Morton, T.A., Pidgeon, N.F. (2015). Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5(12), 1031.

Brulle, R.J., Carmichael, J., Craig Jenkins, J. (2012). Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the us, 2002–2010. Climatic change, 114(2), 169–188.

Camerer, C.F., & Fehr, E. (2002). Measuring social norms and preferences using experimental games: A guide for social scientists. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.299143.

Caporael, L.R., Dawes, R.M., Orbell, J.M., Van De Kragt, A.J.C. (1989). Selfishness examined: Cooperation in the absence of egoistic incentives. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(04), 683. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x00025292.

Chaudoin, S., Smith, D.T., Urpelainen, J. (2013). American evangelicals and domestic versus international climate policy. The Review of International Organizations, 9(4), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-013-9178-9.

Ciplet, D., Roberts, J.T., Khan, M.R. (2015). Power in a Warming World: The new global politics of climate change and the remaking of environmental inequality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dawes, C.T., Loewen, P.J., Fowler, J.H. (2011). Social preferences and political participation. Journal of Politics, 73(3), 845–856.

Deryugina, T. (2013). How do people update? the effects of local weather fluctuations on beliefs about global warming. Climatic change, 118(2), 397–416.

Diamond, A., & Sekhon, J.S. (2013). Genetic matching for estimating causal effects A general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 932–945.

Duflo, E. (2001). Schooling and labor market consequences of school construction in indonesia: Evidence from an unusual policy experiment. American Economic Review, 91(4), 795–813.

Dunlap, R.E., & McCright, A.M. (2011). Organized climate change denial. The Oxford handbook of climate change and society, 1, 144–160.

Duray, D. (2007). Bush endorses climate study: Reverses stance on warming. Montery Herald, 2.

Egan, P.J., & Mullin, M. (2012). Turning personal experience into political attitudes: The effect of local weather on americans’ perceptions about global warming. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 796–809. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381612000448.

Egan, P.J., & Mullin, M. (2017). Climate change: Us public opinion. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 209–227.

Engel, C. (2011). Dictator games: a meta study. Experimental Economics, 14, 583–610.

Engelmann, D., & Strobel, M. (2004). Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments. American Economic Review, 94(4), 857–869. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828042002741.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K.M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J.L., Savin, N.E., Seften, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6, 347–369.

Fricke, H. (2017). Identification based on difference-in-differences approaches with multiple treatments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 79(3), 426–433.

Gelman, A., Park, D.K., Ansolabehere, S., Price, P.N., Minnite, L.C. (2001). Models, assumptions and model checking in ecological regressions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 164(1), 101–118.

Gelman, A. (2009). Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State: Why Americans Vote the Way They Do-Expanded Edition. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Gintis, H., Bowles, S., Boyd, R., Fehr, E. (2003). Explaining altruistic behavior in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(3), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(02)00157-5.

Goebbert, K., Jenkins-Smith, H.C., Klockow, K., Nowlin, M.C., Silva, C.L. (2012). Weather, climate, and worldviews: the sources and consequences of public perceptions of changes in local weather patterns. Weather, Climate, and Society, 4 (2), 132–144.

Glynn, A.N., & Wakefield, J. (2010). Ecological inference in the social sciences. Statistical Methodology, 7(3), 307–322.

Guber, D.L. (2012). A cooling climate for change? party polarization and the politics of global warming. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463361.

Guth, J.L., Green, J.C., Kellstedt, L.A., Smidt, C.E. (1995). Faith and the environment: Religious beliefs and attitudes on environmental policy. American Journal of Political Science, 364–382.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., Haggard, S., Lake, D.A., Victor, D.G. (2017). The behavioral revolution and international relations. International Organization, 71(S1). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818316000400.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011a). Money for nothing? universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11-12), 1455–1465.

Havnes, T., & Mogstad, M. (2011b). No child left behind: Subsidized child care and children’s long-run outcomes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3 (2), 97–129.

Ho, D.E., Imai, K., King, G., Stuart, E.A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236.

Hoell, A., Perlwitz, J., Dewes, C., Wolter, K., Rangwala, I., Quan, X.-W., Eischeid, J. (2019). Anthropogenic contributions to the intensity of the 2017 United States northern great plains drought. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100(1), S19–S24.

Hope, A.L.B., & Jones, C.R. (2014). The impact of religious faith on attitudes to environmental issues and carbon capture and storage (ccs) technologies: a mixed methods study. Technology in Society, 38, 48–59.

Holmes, M., & Yarhi-Milo, K. (2016). The psychological logic of peace summits: How empathy shapes outcomes of diplomatic negotiations. International Studies Quarterly, 61(1), 1–16.

Holtz-Eakin, D., Joulfaian, D., Rosen, H.S. (1993). The carnegie conjecture: Some empirical evidence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 413–435.

Hornsey, M.J., Harris, E.A., Bain, P.G., Fielding, K.S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2943.

IPCC. (2007). A report of working group i of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Summary for policy makers Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

IPCC. (2014). Ar5 synthesis report: Climate change 2014. Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Jacques, P.J., Dunlap, R.E., Freeman, M. (2008). The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environmental politics, 17 (3), 349–385.

Johnston, R.J., Bond, A.J., Mitchell, D., Cromley, E., Corbridge, S. (1998). A solution to the ecological inference problem: Reconstructing individual behavior from aggregate data: Environmental and social impact assessment: An introduction, the city: Los angeles and urban theory at the end of the twentieth century, spatial behavior: A geographic perspective, private capital flows to developing countries: The road to financial integration.

Joireman, J., Truelove, H.B., Duell, B. (2010). Effect of outdoor temperature, heat primes and anchoring on belief in global warming. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 358–367.

Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D., Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L., Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business, 59, S285–S300.

Kertzer, J.D., & Rathbun, B.C. (2015). Fair is fair: social preferences and reciprocity in international politics. World Politics, 67 (04), 613–655. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887115000180.

Kim, S.Y., & Wolinsky-Nahmias, Y. (2014). Cross-national public opinion on climate change: The effects of affluence and vulnerability. Global Environmental Politics, 14(1), 79–106.

King, G. (1997). A Solution to the Ecological Inference Problem: Reconstructing individual behavior from aggregate data. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Knight, K.W. (2016). Public awareness and perception of climate change: a quantitative cross-national study. Environmental Sociology, 2(1), 101–113.

Konisky, D.M., Hughes, L., Kaylor, C.H. (2016). Extreme weather events and climate change concern. Climatic Change, 134(4), 533–547.

Kvaloy, B., Finseraas, H., Listhaug, O. (2012). The publics’ concern for global warming: a cross-national study of 47 countries. Journal of Peace Research, 49 (1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311425841.

Lake, D. (2009). Open economy politics: A critical review. Review of International Organizations, 4, 219–244.

Lee, T.M., Markowitz, E.M., Howe, P.D., Ko, C.-Y., Leiserowitz, A.A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2728.

Leiserowitz, A., & et al. (2007). International public opinion, perception, and understanding of global climate change. Human Development Report, 2008, 1–40.

Li, Y., Johnson, E.J., Zaval, L. (2011). Local warming: Daily temperature change influences belief in global warming. Psychological science, 22(4), 454–459.

Lo, A.Y., & Chow, A.T. (2015). The relationship between climate change concern and national wealth. Climatic Change, 131(2), 335–348.

Lorenzoni, I., & Pidgeon, N.F. (2006). Public views on climate change European and usa perspectives. Climatic Change, 77(1-2), 73–95.

Lü, X., Scheve, K., Slaughter, M.J. (2012). Inequity aversion and the international distribution of trade protection. American Journal of Political Science, 56(3), 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00589.x.

Mansfield, E.D., & Mutz, D.C. (2009). Support for free trade Self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. International Organization, 63(03), 425. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818309090158.

Mansfield, E.D., & Mutz, D.C. (2013). Us versus them. World Politics, 65(4).

Marx, S.M., Weber, E.U., Orlove, B.S., Leiserowitz, A., Krantz, D.H., Roncoli, C., Phillips, J. (2007). Communication and mental processes: Experiential and analytic processing of uncertain climate information. Global Environmental Change, 17(1), 47–58.

Mccright, A.M. (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the american public. Population and Environment, 32(1), 66–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-010-0113-1.

McCright, A.M., & Dunlap, R.E. (2003). Defeating kyoto: the conservative movement’s impact on us climate change policy. Social problems, 50(3), 348–373.

Mccright, A.M., & Dunlap, R.E. (2011). Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the united states. Global Environmental Change, 21(4), 1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

Mcdonald, R.I, Chai, H.Y, Newell, B.R. (2015). Personal experience and the ’psychological distance’of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109–118.

Min, S.-K., Kim, Y.-H., Park, In-H., Lee, D., Sparrow, S., Wallom, D., Stone, D. (2019). Anthropogenic contribution to the 2017 earliest summer onset in south korea. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100(1), S73–S77.

Moon, B.K. (2014). Secretary-general’s remarks at climate leaders summit. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2014-04-11/secretary-generals-remarks-climate-leaders-summit.

Nisbet, M.C., & Myers, T. (2007). The polls trends: Twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(3), 444–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfm031.

Poortinga, W., Spence, A., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S., Pidgeon, N.F. (2011). Uncertain climate: an investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Global environmental change, 21(3), 1015–1024.

Rathbun, B.C., Kertzer, J.D., Reifler, J., Goren, P., Scotto, T.J. (2016). Taking foreign policy personally; Personal values and foreign policy attitudes. International Studies Quarterly, 60, 124–137.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Rees, M. (2007). Uk scientists’ ipcc reaction. BBC (pp. 2).

Sandvik, H. (2008). Public concern over global warming correlates negatively with national wealth. Climate Change, 90(3), 333–341.

Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. (2013). American evangelicals and global warming. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1009–1017.

Steg, L., & De Groot, J. (2012). Environmental values. In Clayton, S.D. (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Triandis, H.C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696169.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440.

Watkins, K. (2007). Human development report 2007/2008. United Nations Development Program.

Weber, E.U. (2006). Experience-based and description-based perceptions of long-term risk: Why global warming does not scare us (yet). Climatic change, 77 (1–2), 103–120.

Weber, E.U. (2010). What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change, 1(3), 332–342.

Whitmarsh, L. (2008). Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? the role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. Journal of risk research, 11(3), 351–374.

Wike, R. (2016). What the world thinks about climate change in 7 charts. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/18/what-the-world-thinks-about-climate-change-in-7-charts/.

Yaari, M.E., & Bar-Hillel, M. (1984). On dividing justly. Social Choice and Welfare, 1(1), 1–24.

Zaval, L., Keenan, E.A., Johnson, E.J., Weber, E.U. (2014). How warm days increase belief in global warming. Nature Climate Change, 4(2), 143.

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments and suggestions I thank Faisal Ahmed, Neal Beck, Carissa T. Block, Sanford Gordon, Alex Kustov, Helen V. Milner, Julia Morse, and Tyler Pratt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kennard, A. My Brother’s Keeper: Other-regarding preferences and concern for global climate change. Rev Int Organ 16, 345–376 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09374-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09374-w