Abstract

This study investigates the extent to which speakers of American Norwegian (AmNo), a heritage language spoken in the United States and Canada, use the indefinite article in classifying predicate constructions (‘He is (a) doctor’). Despite intense contact with English, which uses the indefinite article, most AmNo speakers have retained bare nouns, i.e., the pattern of Norwegian as spoken in Norway. However, a minority of the speakers use the indefinite article to some extent. I argue that generally, this use of the indefinite article has arisen through attrition (i.e., a change during the lifetime of individuals), not through divergent attainment causing systematic, parametric change in the Norwegian grammar of these speakers. I also argue that representational economy is one of the factors that may have contributed to the relative stability of bare nouns.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Norwegian as spoken in Norway (hence European Norwegian, or EurNo) allows bare, singular nouns in some contexts where English does not. Perhaps the most conspicuous difference concerns post-copular, singular predicate nouns: in English, most of such nouns must appear with an indefinite article; EurNo, on the other hand, uses bare nouns when the predicate is, for example, a profession, role or nationality. Compare (1) and (2):Footnote 1

This study investigates the use of bare nouns versus nouns with an indefinite article in American Norwegian (AmNo), a heritage language spoken in the United States and Canada.Footnote 2 AmNo speakers are bilingual; today, they are typically third- or fourth-generation Norwegian immigrants who have acquired Norwegian at home as young children, and then English when starting school. The extent to which they have had contact with the speech community in Norway varies; however, English is their dominant language, and most speakers have been to Norway just a few times or not at all.Footnote 3 Present-day speakers are mostly of a mature age and have not passed the language on to the next generation; AmNo can therefore be classified as a moribund variety.

The empirical starting point and main focus of this study are sentences with a human subject, a copula verb and a predicate noun, such as in (1)–(2). The patterns found in these predicate constructions can serve as windows into the variation in the structure of nominal phrases more generally: they can be indicative of whether a language allows small nominal phrases that lack a functional projection for Number (Munn and Schmitt 2002, 2005; Deprez 2005; see also Pereltsvaig 2006). Studying this variation in the context of AmNo is particularly interesting; it can contribute to our understanding of syntactic variation and change in contact situations, given the intense contact between AmNo and English.

The research questions addressed are the following: First, in syntactic environments where English and EurNo differ in terms of using bare nouns versus nouns with an indefinite article, which patterns are preferred by AmNo speakers? Previous studies of AmNo have observed syntactic variation and change both in the verbal and nominal domain (e.g., Eide and Hjelde 2015; Larsson and Johannessen 2015; Westergaard and Andersen 2015; Riksem 2017; 2018), but to date, the distribution of bare nouns versus nouns with an indefinite article has not been systematically investigated. An interesting comparative backdrop is formed by Hasselmo’s (1974) and Heegård Petersen’s (2018) observations from American Swedish and American Danish, which indicate some English-like use of articles in these varieties. Second, if some or all AmNo speakers deviate from the EurNo patterns, what kind(s) of change is/are at work? This question is discussed in the context of a distinction between divergent attainment and attrition, and in the framework of a recent version of parametric theory (Biberauer et al. 2014; Biberauer 2017; Biberauer and Roberts 2017; Roberts 2019). I show that most speakers of AmNo use bare nouns like in EurNo; there is thus a high degree of stability, which contrasts with certain other aspects of AmNo syntax—notably, word order in subordinate clauses (Taranrød 2011; Larsson and Johannessen 2015) and double definiteness (Anderssen et al. 2018; van Baal 2018, 2020). At the same time, although it is not very frequent, the indefinite article occurs to a non-negligible extent. I argue that this use of the indefinite article in AmNo in most cases seems to be due to attrition in the lifespan of individual speakers and not a more systematic, parametric change resulting from divergent attainment. The argument is partly based on the distribution of the indefinite article in predicate constructions across speakers. I also argue that in a case of parametric change, one might expect to see concomitant changes affecting bare nouns in argument/adjunct positions, which are also a feature of EurNo syntax (e.g., Borthen 2003, and changes in the representation of Number (e.g., Munn and Schmitt 2002, Munn and Schmitt 2005). There are no clear indications of this.

The paper is organised as follows: In Sect. 2 I give a more detailed description of predicate nouns in EurNo; a central notion is the distinction between classifying and descriptive predicates. In Sect. 3 I present the AmNo data. In Sect. 4 I revisit EurNo and argue that bare nouns are underspecified for Number; I discuss both bare predicate nouns and bare nouns in argument/adjunct positions. Section 5 analyses the variation between predicate nouns with and without the indefinite article in AmNo. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Predicate nouns in European Norwegian

This section provides a more detailed description of predicate nouns in EurNo, which is the baseline to which AmNo will be compared. In Sect. 2.1 I discuss the methodology, and in 2.2 I present the difference between two types of predicate nouns (classifying versus descriptive).

2.1 Methodology

The ideal baseline for this study of AmNo would be the language of the early Norwegian emigrants who settled in North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (see also e.g., Larsson and Johannessen 2015, 160).Footnote 4 However, our access to this language is currently very limited,Footnote 5 and for practical reasons, I follow previous studies (e.g., Larsson and Johannessen 2015; Lohndal and Westergaard 2016; and others) in using data from Norwegian as currently spoken in Norway (EurNo) to represent the baseline. EurNo today is well documented, both in the grammatical literature and linguistic corpora, and I draw on both types of sources to establish the baseline. A particularly valuable resource is the Nordic Dialect Corpus (Johannessen et al. 2009), which provides spontaneous speech data that are comparable to the AmNo data used in this study in terms of collection methods. The corpus also allows us to control for factors such as geographical origin in Norway.

2.2 Classifying versus descriptive predicates

Previous literature has shown that drawing a distinction between classifying and descriptive predicates in Norwegian and, more generally, Mainland Scandinavian, is useful (Delsing 1993, 32; Julien 2005,255ff; see also Dyvik 1979 and Faarlund et al. 1997, who use a different terminology). In informal terms, classifying predicates denote a set of which the subject is a subset (Faarlund et al. 1997, 733). Descriptive predicates, on the other hand, denote a property associated with the subject; moreover, they often convey the speaker’s evaluation. The two types of predicates differ in that the indefinite article is typically used with the latter but not with the former; this distinction holds when the subject is human (Halmøy 2001, 6).Footnote 6 Cf. the sentence pair in (3):

The predicate noun in (3a) is classifying; it thus appears in the bare form. The predicate noun in (3b), on the other hand, is descriptive; it thus appears with the indefinite article en.

Typically, classifying predicates with a human subject denote professions, roles, nationalities and religions. They also tend to appear without any adjectival modifiers, although this is not an absolute rule (cf. Borthen 2003; Julien 2005 for discussion). Conversely, descriptive predicates are often modified, e.g., by an adjective, such as in (3b). However, they may also be unmodified, particularly if they are inherently evaluative. This is illustrated in (4):

The difference between English and EurNo that was introduced in Sect. 1 concerns classifying predicate nouns; these predicates will be the focus of the remainder of the paper.Footnote 7 Table 1 illustrates how classifying predicate nouns are used by speakers in the Nordic Dialect Corpus. For reasons of scope, and in an attempt to make the sample resemble the language of the first emigrants as closely as possible, only a subset of the corpus was queried, amounting to 911,898 word tokens from 246 speakers, selected on the basis of geography and age: I included data from the regions Østlandet, Vestlandet and Trøndelag (Eastern, Western and Central Norway),Footnote 8 and speakers defined as belonging to age group B in the corpus metadata, i.e., speakers over 50 years old. I searched for strings containing any form of the copula verbs være ‘be’ and bli ‘become’ followed by a singular, indefinite noun (and, potentially, an indefinite article). The interval between the verb and the noun was a maximum of 4 word tokens. I examined the hits manually; Table 1 includes instances which meet the following criteria: (i) The subject is singular and human. (ii) The predicate noun is not clearly subjectively characterising/evaluative, and it is not modified by any adjectives, relative clauses or determiners (including sånn and slik ‘such’). (iii) The predicate noun is not clearly a unique title (I excluded e.g., ordfører ‘mayor’, lensmann ‘District Sheriff’ and direktør ‘manager’).Footnote 9

As is evident from Table 1, EurNo speakers almost always (in 98.1% of the cases) used bare nouns in classifying predicate constructions. There are four counterexamples, two of which involve the noun smågutt ‘little boy’, as illustrated in Example (5).

Presumably, the two speakers who produce strings like (5) treat smågutt as a modified, descriptive predicate, although the adjective små ‘small’ formally forms a compound with the noun.Footnote 10 The two remaining counterexamples are produced by two different speakers, but they are similar in that they both involve military titles (befalingsmann ‘commissioned officer’ and underoffiser ‘subordinate officer’). I currently have no account for them. For the present purposes, I abstract away from this and treat the use of bare nouns in the relevant EurNo predicate constructions as nearly categorical.Footnote 11

3 Predicate nouns in American Norwegian

Having discussed predicate nouns in the EurNo baseline, I now turn to predicate nouns in AmNo. Section 3.1 discusses the methodology used, and Sect. 3.2 presents the results.

3.1 Methodology

The AmNo data are partly drawn from the Corpus of American Norwegian Speech (CANS) (Johannessen 2015) and partly collected during a field trip in 2016. A few additional, untranscribed recordings from 2010–2012 were also used. CANS consists of spontaneous speech (mostly interviews) from 50 speakers of AmNo; at the time of data collection, the size of the corpus was 184,307 word tokens, according to the corpus metadata.Footnote 12 The additional data collected during the 2016 field trip are semi-structured interviews/conversations with 28 speakers, some of whom have been interviewed for CANS on previous occasions. Some of the questions were designed to prompt classifying predicates (e.g., What is your profession?). I also showed the speakers some simple pictures and asked them to tell me about what they saw (e.g., a picture of a person buying an airplane ticket. This would be a possible context for a bare type noun in EurNo, see Sect. 4.2). I also conducted a storytelling task based on a picture book (Journey by Aaron Becker 2013).Footnote 13

I extracted classifying predicate nouns by using the same criteria as for the EurNo sample described in Sect. 2.2.Footnote 14 Thus, the AmNo data set includes predicate nouns that are singular count nouns, not modified by adjectives/relative clauses, not evaluative, not unique titles/roles, and whose subjects are human and singular.Footnote 15 Some of the predicate nouns are borrowed from English (I return to this in Sect. 5.2); all indefinite articles included in the study are Norwegian.Footnote 16

3.2 Results: classifying predicate nouns sometimes occur with an indefinite article

I found classifying predicate nouns meeting the above-mentioned criteria in 47 speakers (a total of 69 speakers were included in the study). Most predicates denote professions, roles and inhabitant names; a few examples are given in (6). In (6a–b) there is no indefinite article; in (6c) the indefinite article is used:Footnote 17

Table 2 shows the total occurrences of bare predicate nouns versus predicate nouns with the indefinite article in the AmNo sample.Footnote 18

As is evident from Table 2, bare nouns are used in the majority of cases (86.4%), but the indefinite article is also attested to a non-negligible extent (13.6%). Recall from Sect. 2.2 that the figure for EurNo was 1.9%; the difference between AmNo and EurNo is statistically significant (Fisher Exact test, \(p < 0.001\)). An overview of how bare nouns versus nouns with the indefinite article are distributed by speaker is given in Table 3. From Table 3, some general patterns can be discerned. First, most speakers consistently use bare nouns. Second, out of the speakers who produce predicate constructions with an indefinite article, very few are consistent; most of them also use predicate constructions with a bare noun.

The amount of data per speaker is generally low; most speakers only produce a few instances of classifying predicate nouns. However, 11 speakers produce the classifying predicate construction five times or more; see Table 4. If we take a closer look at these speakers, the following points can be noted: 6 out of 11 speakers consistently use bare nouns. The three speakers with the most attestations of classifying predicate constructions belong to this group (coon_valley_WI_06gm with 21 examples, fargo_ND_10gm with 17 examples and webster_SD_01gm with 10 examples). Two speakers use bare nouns in all but one case (rushford_MN_01gm and vancouver_WA_01gm). One speaker, stillwater_MN_01gm, exhibits a very mixed pattern: 5 bare nouns and 4 nouns with the indefinite article. One speaker, portland_ND_02gk, consistently uses the indefinite article (5 times); another, sunburg_MN_16gm, uses it 4 out of 5 times.

To sum up, the use of bare predicate nouns in AmNo is relatively stable, although a minority of speakers use the indefinite article, at least to some extent. Other features of AmNo syntax that exhibit relative stability (abstracting away from some interesting individual variation) are, for example, V2 word order in main clauses (Eide and Hjelde 2015, 85–86) and possessive constructions with a postnominal possessor (bilen min, lit. ‘car-the my’) (Westergaard and Andersen 2015).Footnote 19 By contrast, many AmNo speakers show a diverging word order in subordinate clauses (Taranrød 2011; Larsson and Johannessen 2015). In the nominal domain, the stability of bare predicate nouns differs from the pattern of so-called double definiteness (den grønne boka, lit. ‘the green book-the’), which appears to be more vulnerable; many AmNo speakers tend to drop the pre-adjectival determiner (Anderssen et al. 2018; van Baal 2018, 2020).

The variation between bare predicate nouns and predicate nouns with an indefinite article in AmNo is explored in greater depth in Sect. 5. Before that, however, in the immediately following Sect. 4, we revisit bare nouns in EurNo, now from the point of view of internal syntactic structure.

4 Bare nouns in European Norwegian and the representation of Number

This section discusses the internal structure of bare predicate nouns (Sect. 4.1), other bare nouns (i.e., bare nouns that are arguments/adjuncts, Sect. 4.2), and the role played by Gender in the omission of the indefinite article (Sect. 4.3). I make the case that bare nouns in EurNo are underspecified for Number; later, in Sect. 5, this idea will play an important role in the analysis of predicate nouns in AmNo.

4.1 Bare predicate nouns

Previous studies (Munn and Schmitt 2002, 2005; Deprez 2005; Halmøy 2016) have argued that the difference between English-style versus Norwegian-style (classifying) predicate constructions is indicative of a more general difference in the internal structure of nominals. The difference concerns the syntactic representation of Number (Num). On the accounts of Munn and Schmitt (2002, 2005) and Deprez (2005), English nominals must include Num, which is reflected in the indefinite article in an example like (1a) (He is a doctor). A language such as EurNo (and, e.g., Dutch and many Romance languages) in certain contexts allows nominals without the Num projection; bare predicate nouns are instantiations of this.Footnote 20 Cf. (7) for a sketch of the syntactic structure of a classifying predicate noun in English versus EurNo:Footnote 21

The idea that bare predicate nouns are underspecified for Number is also found in de Swart et al. (2005, 2007) and de Swart and Zwarts (2009). De Swart et al. 2007 relate the lack of a Number projection to a distinction between capacities, on the one hand, and other semantic primitives, such as kinds, on the other hand: bare predicate nouns are NPs and denote capacities, whereas predicate nouns with an indefinite article include at least a NumP, which coerces the capacity denotation into a kind denotation (de Swart et al. 2007, 215; see de Swart et al. 2007, 203ff for further discussion of the special semantic properties of capacities).

Syntactic evidence for the absence of Number in bare predicate nouns comes from predicate agreement. De Swart et al. 2005; 2007 and de Swart and Zwarts (2009) show that in Dutch, it is possible for a bare predicate noun to occur with a plural subject. This is shown in Example (8).Footnote 22

The ability of bare predicate nouns to be combined with a plural subject would be surprising if these nouns were carrying a singular feature, but less so if they are underspecified for Number; if they are underspecified, there is no direct agreement clash.

Bare predicate nouns with a plural subject are also possible in EurNo. In EurNo they are often found in sentences in which the subject is a quantifier or a quantified noun; the presence of future/modal auxiliaries also seems to promote their acceptability. Some attested examples are given in (9) (from the Norwegian Web as Corpus (NoWaC; see Guevara 2010 and www.stortinget.no):Footnote 23

Bare nouns with a plural subject can also be found independently of quantifiers/auxiliaries; two examples from Faarlund et al. (1997) are given in (10a–b), whereas (10c) is from the Nordic Dialect Corpus:

It could be argued (as Faarlund et al. 1997, 762 do) that the lack of plural marking in examples like (9)–(10) arises simply because the predicate noun has a distributive reading, not because Number is absent. However, an analysis along these lines poses some problems. If the bare nouns in (9)–(10) were formally singular nouns with a distributive reading, it is not clear why English seems to allow similar structures to a lesser extent. Cf. the example in (11), modelled on the Norwegian example in (9c).

Whilst the EurNo example in (9c) is unproblematic, the English example in (11) seems to have a dubious status; there are speakers who accept it, but others do not, unless a lawyer is changed to an indefinite plural.Footnote 24 To my knowledge, there are no independent reasons why English would be more restrictive than EurNo in terms of allowing distributive readings. Thus, an account based on absent Number features in Norwegian seems preferable.

In conclusion, I adopt the assumption that bare predicate nouns in EurNo are underspecified for Number. Bare (Num-less) predicate nouns seem to have a narrower distribution in EurNo than in, for example, Dutch, and I currently have no account for the exact conditions under which Num can be missing. However, the important point is that Num-less predicate nouns exist as an option in EurNo, given the right circumstances. This option is not as readily available in English.

4.2 Bare type nouns

Bare nouns do not only occur in predicate contexts in EurNo; they can also be arguments and adjuncts (Borthen 2003; Julien 2005; Grønn 2006; Halmøy 2016; Rosén and Borthen 2017; see, e.g., Schmitt and Munn 2002; Pereltsvaig 2006; Espinal 2010; Espinal and McNally 2011; Alexopoulou et al. 2013; Schulpen 2016 for cross-linguistic perspectives). Some EurNo examples are given in (12) (from Borthen 2003, 60–61):

As shown in (12), EurNo bare nouns can appear in various syntactic positions, for example as subjects, objects, and complements of prepositions. A core observation of Borthen (2003), adopted in much work since (see, e.g., Julien 2005 and Halmøy 2016), is that bare nouns are used to emphasise the type of discourse referent rather than the token instantiated in a given context. I use the term bare type noun to refer to bare nouns such as those cited in example (12).

Now the question is whether bare type nouns have the same syntactic structure as bare predicate nouns, and in particular whether an analysis in terms of underspecification of number is applicable to type nouns too. De Swart et al. (2007, 208) argue that bare nouns in argument positions (including bare type nouns in Norwegian) denote kinds and not capacities; from the perspective of their analysis, whereby kind denotation is associated with Num, this could be taken to suggest that Num is present. However, as pointed out by Julien (2005, 255), following Borthen (2003), bare type nouns and bare predicate nouns in EurNo have much in common; they are subject to similar semantic conditions in that both are used in “conventional situation types”; an indication of this is the fact that they both resist adjectival modification (see Sect. 2.2 on modification of predicate nouns). Borthen (2003) and Julien (2005, 284ff) analyse bare predicate nouns and bare type nouns on a par; so does Halmøy (2016, 97), who argues explicitly that bare type nouns are underspecified (or, in her terms, “neutral”) with regard to number. Halmøy observes that bare type nouns can be compatible with plural readings; this is illustrated in (13). Example (13b) is particularly interesting because the bare noun is anaphorically referred to by a plural pronoun.

A diagnostic related to Halmøy’s observations is proposed by Espinal (2010, 989), based on data from Catalan. Under the scope of a plural expression in the sentence, Catalan bare nouns are compatible with a cumulative reading (Krifka 1992), whereas a noun with the indefinite article can only have a distributive reading:Footnote 25

The sentence in (14b) would only be appropriate if there was exactly one account in each of the banks (distributive reading), whereas (14a) could also be used if there was more than one account in any of the banks (cumulative reading). The availability of the cumulative reading with bare nouns suggests that these nouns are underspecified for number; the unavailability of the cumulative reading in the presence of the indefinite article would follow from the singular specification associated with the article.Footnote 26 Turning now to EurNo, a similar pattern can be observed. At least for some speakers, a cumulative reading is possible with a bare type noun in a context similar to the Catalan examples above:Footnote 27

In conclusion, I adopt the idea that bare type nouns in EurNo are underspecified for number.Footnote 28

4.3 Absence of Number and presence of Gender

A question that arises at this point is whether the availability of small, Num-less nominals is randomly distributed across languages or if it could be related to other linguistic features. One such feature that presents itself in the context of Germanic and Romance is gender: whereas English lacks grammatical gender, gender is found in EurNo, Dutch and French, all of which allow bare predicate nouns. Additionally, comparing Afrikaans and Dutch is relevant: Dutch, as mentioned, has grammatical gender and regularly uses bare, classifying predicate nouns. Afrikaans, on the other hand, has lost gender, and generally uses the indefinite article in classifying predicate constructions (Donaldson 1993, 65).Footnote 29 Moreover, Afrikaans, as opposed to Dutch, does not allow a bare predicate noun to appear with a plural subject; plural agreement is required (Theresa Biberauer, p.c.). This can be interpreted as an indication that Num is obligatorily present (see Sect. 4.1).

Munn and Schmitt (2002, 2005) capture the correlation between the absence of Num and the presence of gender indirectly by applying the Free Agr Parameter (Bobaljik 1995; Giorgi and Pianesi 1997; Bobaljik and Thráinsson 1998) to the nominal domain. In Romance languages, Num and Agr are distinct (“free”) heads (Num is the locus of an interpretable Num feature, whereas Agr is the locus of uninterpretable \(\upvarphi \)-features, including Gender (Gen)). This assumption is motivated by distinct DP-internal agreement in gender and number in Romance (the analysis could be extended to EurNo). In English, on the other hand, there is no Gen or Num agreement in nominal phrases,Footnote 30 which is taken to mean that Agr and Num are fused in the same head. For illustration, cf. (16) (modelled on Munn and Schmitt 2002, 230).

According to Munn and Schmitt (2002, 230), free features, as opposed to fused features, can be omitted when not semantically required. In predicate nouns, an interpretable Num feature is not strictly necessary, as “the interpretable Num feature would be present on the subject of predication.” The indefinite article in English spells out the singular value of Num, which cannot be omitted because it is fused with Agr. An English classifying predicate noun (like in He isa doctor) therefore has a structure like (17a). In Romance (and EurNo), omitting Num is possible because Agr and Num are free. A bare, classifying predicate noun (as in Norwegian Han erlege lit. ‘He is doctor’) would have a structure as sketched in (17b).

Separate Agr projections have been challenged on the grounds that they lack independent motivation (e.g., Chomsky 1995, 349ff), and exploring alternative ways of analysing the correlation between the omission of Num and the presence of gender would be interesting (see Kramer 2016a, b on the structural location of gender features).Footnote 31 For the present purposes, the formal implementation is not crucial; I assume, however, that the absence of gender in English is of relevance to the obligatoriness of the indefinite article.

5 Analysing the variation in American Norwegian

In Sect. 3 it was shown that bare predicate nouns are generally stable in AmNo, but that predicate constructions with an indefinite article are attested to a non-negligible extent in a subset of the data. In this section I discuss how this use of the indefinite article might have arisen. The section is structured as follows: In Sect. 5.1 I present the difference between two types of syntactic variation and change in heritage languages: divergent attainment (which, in my analysis, results in parametric change) and attrition. In Sects. 5.2 and 5.3 I discuss two hypotheses based on divergent attainment/parametric change; I argue that these are not well suited to account for the distributional patterns of bare nouns in AmNo. In Sect. 5.4 I propose an account based on attrition.

5.1 Divergent attainment and attrition

Variation and change in heritage languages have been attributed to a large number of factors. Illustratively, Benmamoun et al. (2013, 166) mention “differences in attainment..., attrition over the lifespan, transfer from the dominant language, and incipient changes in parental/community input that get amplified in the heritage variety.” Johannessen (2018, 2) mentions “incomplete acquisition and attrition, transfer and convergence, processing, memory, complexity and overgeneralisation”. The question of how these factors relate to one another is not always discussed, but from the viewpoint of generative, diachronic syntax, which is my point of departure, one can distinguish between two types of change: the first type is indicative of innovation in I-languages as they emerge in children during (first) language acquisition (Lightfoot 2017). The second type arises during the lifetime of a speaker, after the I-language has been fully acquired, and is related to a lack of use of the heritage language in combination with the presence of the majority language. I use the terms divergent attainment and attrition to refer to the two types of change, and treat the distinction between them as fundamental. Other factors, such as memory, processing, transfer and overgeneralisation, can be subsumed under these two main categories.Footnote 32

The term divergent attainment is taken from Polinsky (2018) and replaces the term incomplete acquisition, which has been commonly used in the heritage language literature, but also much criticized (see, e.g., Putnam and Sánchez 2013 and Kupisch and Rothman 2016). Note that I use the term divergent attainment (and also the term attrition) in a wider sense than some other authors do (see, e.g., Montrul 2008; Schmid 2011; Benmamoun et al. 2013); in the definition adopted here, divergent attainment is, in principle, no different from general language change. The trigger for change may be particular to heritage languages in that it relates to reduced or divergent input, but the basic process is the same as in non-heritage languages: new generations develop I-languages that are slightly different from those of their parents (Andersen 1973; Lightfoot 1979, 1999; Roberts 2017, 134). I take divergent attainment of syntax to result in parametric change in the sense of Biberauer et al. (2014), Biberauer (2017), Biberauer and Roberts (2017), and Roberts (2019). In this framework parametric variation and change are analysed in terms of features on lexical items (in accordance with the Borer-Chomsky conjecture, see Baker 2008). Parameters can be classified according to “size”, ranging from macroparameters to nanoparameters, depending on the classes of lexical items to which they apply.

Attrition, in the definition used here, can take many shapes, ranging from problems with lexical retrieval to morphosyntactic irregularities. The term attrition is commonly used to refer to the “loss of linguistic skills in a bilingual environment”; if it has morphosyntactic consequences, it is typically implied that “a given grammatical structure reached full mastery before weakening or becoming lost...” (Polinsky 2018, 22). In other words, attrition does not affect the emergence of the I-language; instead, it takes place later in the lifetime of a speaker, and it is often described as a more superficial phenomenon than divergent attainment. Montrul (2008, 65) writes: “attrition in adults affects primarily performance (retrieval, processing and speed), but does not result in incomplete or divergent grammatical representations...”. It has been argued that attrition may also have more profound effects on syntactic structure, affecting the “linguistic knowledge established in childhood” (Polinsky 2018, 22).Footnote 33 However, this seems to be primarily restricted to cases in which L1 and L2 are closely related, or cases in which attrition of the L1 sets in at a young age (Schmid and Köpke 2017, 655, 658 and references therein; see also Polinsky 2018, 22–23). When systematically divergent patterns emerge in young speakers, the question arises as to where one should draw the line between divergent attainment and attrition. Schmid and Köpke (2017, 658) note that attrition effects in the L1 of post-puberty bilinguals are typically more limited than among speakers whose onset of L2 acquisition is early; they suggest that there is “either an extended period of entrenchment or some kind of stabilization effect after the rule has been acquired” that can “decrease vulnerability to erosion” (see also Schmid 2012). Another way of capturing the observation that systematic L1 “attrition” on the level of grammatical representation mostly happens early in life, could be to say that the L1 is not fully acquired until after this stabilisation period. If one takes that perspective, early attrition (in cases in which the effects are so profound that they seem to affect grammatical representation) could be equated with divergent attainment.

In what follows I discuss three approaches to the variation between bare predicate nouns and predicate nouns with an indefinite article in AmNo. Two of them imply that the variation results from divergent attainment (i.e., parametric change); I will argue that these approaches are not easy to reconcile with the distribution of bare nouns versus nouns with indefinite articles (Sects. 5.2 and 5.3). In Sect. 5.4 I argue that an account based on attrition is more plausible.

5.2 Lexical borrowing with grammatical effects?

The limited distribution of the indefinite article in predicate constructions makes it relevant to ask if the article might correlate with certain lexical items. This could potentially be consistent with the patterns observed in Sect. 3; in particular, intra-speaker variation, which is characteristic of the use of the indefinite article (see Table 3), would be easy to explain. A possible scenario is that the distribution of the article is related to lexical borrowing: when borrowing English nouns, AmNo speakers have not only adopted phonological and semantic features but also the syntactic requirement for an article. Previous observations of predicate constructions in American Swedish make a hypothesis along these lines particularly relevant. According to Hasselmo (1974, 216), American Swedish speakers prefer to include the indefinite article if the predicate noun is borrowed from English; if the predicate noun is Swedish, the use and non-use of the article are more or less equally acceptable.Footnote 34 If the indefinite article is associated with certain borrowed lexical items, it can be conceived of as a small-scale, contact-driven parametric change (Roberts 2007, 236ff) (a nano or possibly microparametric change in the terminology of Biberauer et al. 2014; Biberauer and Roberts 2017, and Roberts 2019).

The idea of the indefinite article being related to lexical borrowing implies certain predictions: there should be a correlation between nouns of English origin and the use of the indefinite article. The article would not necessarily have to be restricted to borrowed nouns; the use could eventually have been extended to other nouns via lexical diffusion. One would, however, expect the article to be more common with loan words.Footnote 35

To test whether there is a correlation between loan words and the use of the indefinite article in AmNo, I annotated the predicate nouns in the data set as either English (e.g., nurse, farmer, and mason) or Norwegian (e.g., sjømann ‘sailor’, lærer ‘teacher’, and snekker ‘carpenter’). I made no attempt to distinguish between loan words and (one-word) codeswitching (see, e.g., Poplack et al. 1988 and Myers-Scotton 1993 for discussion; cf. also Annear and Speth 2015 on lexical transfer in AmNo).Footnote 36 The results are summarised in Table 5.

As is evident from Table 5, English and Norwegian predicate nouns pattern in a rather similar way; Norwegian nouns occur slightly more often with the indefinite article (14.4% for Norwegian nouns versus 11.4% for English nouns), but the difference is not statistically significant (Fisher Exact test, p = 0.8007).Footnote 37 Thus, my data do not corroborate the idea that the use of the indefinite article is directly related to lexical borrowing.Footnote 38 For further illustration of how the presence or absence of the indefinite article seems to be independent of the origin of the predicate noun, cf. examples (18a–b), in which English loan words occur without the indefinite article, and (18c–d), in which non-borrowed Norwegian predicate nouns occur with the article.

The figures in Table 5 are based on the data set as a whole. It is also relevant to consider the distribution in individual speakers who use the article sometimes. A potentially interesting case would be the speaker stillwater_MN_01gm, who displays 4 instances of predicate constructions with an indefinite article and 5 instances with a bare noun. However, this speaker does not use any borrowed predicate nouns, so the variation is not related to borrowing.

I conclude that the use of the indefinite article in predicate constructions did not arise as a direct, grammatical consequence of lexical borrowing. However, this, in itself, does not exclude the possibility that it should be conceived of as a parametric change resulting from divergent attainment. This is explored further in the next section (5.3).

5.3 Extension of Num to new contexts?

Compared with previous generations, today’s AmNo speakers might possibly have analogically extended the Num projection to more syntactic contexts, independently of lexical borrowing.Footnote 39 For heuristic reasons, my point of departure in the following sections will be a strong hypothesis, namely that the use of the indefinite article is a sign of a parametric change whereby Num has become obligatory, as is arguably the case in English (see Sect. 4.1). I will consider three types of evidence: i) the distribution of the indefinite article in classifying predicate constructions, within and across speakers, ii) predicate agreement, and iii) the extent to which AmNo speakers allow bare type nouns, i.e., bare nouns that are arguments/adjuncts instead of predicates. I will also briefly discuss whether the status of grammatical gender in AmNo corroborates the idea of an extension of Num.

5.3.1 Distribution of the indefinite article

If the presence of indefinite articles in classifying predicate constructions is indicative of Num becoming obligatory, there is reason to expect, at least as a starting point, that speakers who use the indefinite article will do so relatively consistently. This prediction derives from the assumption that parametric change is, in essence, abrupt; on the level of individual speakers, change is not gradual (Lightfoot 1999; Roberts 2007, 293ff; see also Polinsky 2018, 28, who makes the same point from a heritage language perspective, describing divergent attainment: “...divergent attainment is different from attrition and transfer; the latter two may be less systematic, whereas the former results in a coherent grammar”). Inter-speaker variation can be expected to occur; this can be understood as variation between innovative speakers with a new grammar and conservative speakers who still have the old type of grammar. Intra-speaker variation, on the other hand, is not immediately accounted for (unless it follows patterns relating to, for example, register or information structure; I return to this shortly).

Now, as mentioned in Sect. 3, the distribution of the indefinite article in AmNo is not characterised by intra-speaker consistency; most speakers who use the indefinite article also produce classifying predicate constructions with bare nouns (cf. Table 3 for a full overview).Footnote 40 For some of the speakers, the indefinite article is clearly the exception rather than the rule; rushford_MN_01gm uses bare nouns 7 times and the indefinite article 1 time; the figures for vancouver_WA_01gm are 4 to 1 (cf. Table 3). Speakers who use the indefinite article consistently or almost consistently (portland_ND_02gk, 5 out of 5 times, and sunburg_MN_16gm, 4 out of 5 times) are atypical.

To reconcile the idea of an extension of Num with the observed intra-speaker variation, one could hypothesise that Num has been extended only to some specifically defined new syntactic contexts, without becoming obligatory across the board. Such a change could be seen as micro or nano parametric in the sense of Biberauer and Roberts (2017) and Roberts (2019); note that the use could still be considered consistent, although it would only apply to a narrower range of contexts. Westergaard (2017) shows, via several case studies, how diachronic change can progress in small but discrete stages; for example, some Norwegian dialects have lost the V2 word order in wh-questions in what appears to be a stepwise process in which factors such as information structure and the syntactic function of the wh-element define the possible contexts for non-V2. The question arises, however, as to which syntactic contexts might be relevant for the use of the indefinite article. I have not been able to spot any systematic properties that distinguish the cases in which the article is used.

The observed intra-speaker variation could also possibly reflect multiple (‘competing’) grammars possessed by individual speakers (Kroch 1989, 1994; Roeper 1999). This would mean that the relevant speakers have one grammar in which Num can be omitted and another grammar in which it cannot; variation between bare predicate nouns and predicate nouns with the indefinite article would arise when speakers switch between the two grammars. However, this account also raises new and challenging questions. According to Roeper (1999), the switch between two grammars does not happen at random; it is motivated by speech register and, in some cases, restricted to certain subclasses of lexical items (see also Roberts 2007, 325).Footnote 41 There are no clear stylistic effects or lexical restrictions on the indefinite article in classifying predicate constructions. Illustratively, within a time interval of just a few seconds, fargo_ND_01gm uses the same noun, guide, both with and without the indefinite article:

The caveat remains that there might exist systematic patterns that were not detected using the present data and methodology. However, as it stands, the distribution of the indefinite article (with very few exceptions) lends no support to the hypothesis of an extension of the Num feature.Footnote 42

5.3.2 Predicate agreement

As mentioned in Sect. 4.1, an argument for analysing bare predicate nouns as Num-less comes from the fact that they may, under certain conditions, be combined with plural subjects. If it could be shown that this is not possible in AmNo, it would corroborate the hypothesis of an extension of Num; obligatory agreement would suggest that Num is not omissible.

However, I have found cases in which a plural subject is combined with a bare noun. This is shown in (20):

The example in (20a) is particularly illustrative; this speaker uses the bare noun nordlending ‘Northener’ as a classifying predicate, and then the (fully expected) plural form of the noun in an adverbial PP.Footnote 43 Example (20a) is noteworthy also because this speaker is among the few who use the indefinite article in predicate constructions with a singular subject relatively consistently (4 out of 5 times, see Table 3). The fact that he uses a bare predicate noun with a plural subject could be interpreted as an argument against analysing his use of the indefinite article in singular contexts as an indication of parametric change; if Num had become obligatory, one would expect plural agreement.

Like in EurNo, bare predicate nouns are not obligatory with plural subjects; there are also plural predicate nouns. However, the data suggest that predicate agreement is not categorically required, contrary to what one would expect if Num had become obligatory.Footnote 44,Footnote 45 The hypothesis of an extension of Num is therefore not corroborated by evidence from predicate agreement.

5.3.3 Type nouns in American Norwegian

Assuming that bare predicate nouns and bare type nouns have the same syntactic structure (see Sect. 4.2), the question arises as to whether AmNo speakers allow bare type nouns. If the use of the indefinite article in predicate constructions is due to the Num feature becoming obligatory, one could reasonably expect to see an effect on type nouns as well; the prediction would be that speakers who use the indefinite article (at least those who use it consistently) should not allow bare type nouns.

Exploring this prediction is methodologically challenging because the use of bare type nouns in EurNo is less categorical than the use of bare predicate nouns. The interpretation changes if the indefinite article is present, but the distinctions are subtle, so finding contexts in which an indefinite article would be completely unacceptable from a EurNo point of view is difficult. On the other hand, if bare nouns are found, this can be taken to indicate that the EurNo structure is retained: whilst the EurNo system permits both bare nouns and nouns with an indefinite article, an English-style system with obligatory Num would not allow bare nouns.

My overall impression is that most speakers seem to have retained bare type nouns. Some examples are given in (21):

It is particularly relevant to see if bare type nouns are used by speakers who use the indefinite article more or less consistently in predicate constructions. The most interesting speakers are, as before, portland_ND_02gk, who consistently uses the indefinite article (5 times), and sunburg_MN_16gm, who uses it 4 out of 5 times.

The speaker portland_ND_02gk produces the following sentence, in which I interpret passport as a bare type noun:Footnote 46

She also produces a few examples of nouns with an indefinite article in contexts in which a type reading would be possible, but as mentioned, no firm conclusions can be drawn on this basis, as the indefinite article would have also been possible in EurNo, with an interpretation that would be only very slightly different.

A similar situation holds for sunburg_MN_16gm. This speaker also exhibits some examples of the indefinite article in contexts in which a type reading of the noun could be possible. But he also produces the following example, which I interpret as a bare type noun:Footnote 47

In conclusion, the available data do not lend any clear support to Num becoming obligatory, as even the speakers who use the indefinite article more or less consistently with predicate nouns produce bare nouns that look like EurNo-style bare type nouns.Footnote 48

5.3.4 A note on gender in American Norwegian

In Sect. 4.3 I argued that grammatical gender plays a role in the possibility of omitting Num in EurNo. This raises the question of whether gender has been retained in AmNo. If gender is lost, it would not be surprising to see a change whereby Num took on some of the previous functions of the Gen feature. This could lead to an extension of Num. Retention of gender, on the other hand, does not provide any motivation for such an extension.

Grammatical gender in AmNo has been investigated in four recent studies: those of Johannessen and Larsson (2015, 2018), Lohndal and Westergaard (2016), and Rødvand (2017). These studies take different positions. Johannessen and Larsson (2015) argue that gender as a grammatical category is retained but that in some speakers, gender agreement is vulnerable in complex constructions because of attrition. Lohndal and Westergaard (2016), on the other hand, argue that some speakers may lack gender completely. Johannessen and Larsson (2015) and Lohndal and Westergaard (2016) use corpus data and focus on DP-internal gender marking; the different conclusions are, to a great extent, caused by different treatments of the definite suffix.Footnote 49 Rødvand (2017, 127, 130) to a greater extent includes experimental data; she concludes that the participants in her study (with one possible exception) have kept at least relics of the EurNo three-gender system. Johannessen and Larsson (2018) focus on gender agreement in pronouns; their findings also corroborate the notion of gender as a productive category.

Given the recent findings by Rødvand (2017) and Johannessen and Larsson (2018), I assume that gender is generally retained in AmNo.Footnote 50 This lends no independent motivation for the hypothesis of an extension of Num.Footnote 51

5.3.5 Intermediate conclusion

Having examined bare predicate nouns versus predicate nouns with an indefinite article in more detail, my position is that the use of the indefinite article in predicate constructions is not due to a parametric change involving an extension of the feature Num to all nominals; in other words, it does not result from divergent attainment. I have shown that there is much intra-speaker variation, and that this variation does not seem to follow any clear patterns. I have also argued that bare type nouns are still present; this is what one would expect when Num-less structures are retained. Finally, I note that the apparent retention of grammatical gender could also be seen as consistent with the retention of Num-less nominals.

5.4 Attrition

Whilst the last two subsections discussed the use of the indefinite article from the perspective of parametric change (resulting from divergent attainment), this section is devoted to attrition. I will argue that an attrition-based account is, overall, more convincing than parametric change, and I propose that attrition in this case can be analysed in terms of the parallel activation of two grammars (Sect. 5.4.1).Footnote 52 In the final section (Sect. 5.4.2) I compare the results from AmNo with those of a recent study of predicate nouns in American Danish (AmDa) (Heegård Petersen 2018). Unexpected use of the indefinite article in AmDa is likely to be due to attrition rather than divergent attainment because many AmDa speakers are first-generation immigrants; therefore, it is relevant to see if the patterns are similar or different in this variety.

5.4.1 Distribution of the indefinite article and resemblance with English

As mentioned, very few speakers use the indefinite article consistently in classifying predicate constructions, and I have not been able to detect any systematic patterns in its distribution. As argued in Sect. 5.3, this is not immediately predicted by a divergent attainment account, but it can be more easily reconciled with attrition. Because attrition sets in after the I-language has been fully acquired and it is typically more performance related, there is more room for intra-speaker variation that does not follow from identifiable lexical, stylistic or discourse-related factors.Footnote 53 The distribution of the indefinite article thus lends itself well to an attrition analysis.

The use of the indefinite article is similar to the pattern found in English, and I assume that it has arisen through English influence.Footnote 54 In principle, this is not incompatible with divergent attainment/parametric change; it could be seen as a case of syntactic borrowing in the course of acquisition.Footnote 55 However, syntactic borrowing is rare, even in contact situations in which one language is under pressure (Winford 2003, 97),Footnote 56 and previous research on AmNo has revealed few, if any, examples of systematic syntactic borrowing from English (see Johannessen 2018 for an overview). I propose that instead of syntactic borrowing into the AmNo I-language, the English-like use of the indefinite article in AmNo results from simultaneous activation of linguistic representations in the bilingual mind. There is a body of research suggesting that bilinguals “cannot simply mentally switch off (de-activate) the other language” (de Groot 2016, 265); speaking one language involves inhibition of the other system, which remains active (see Bialystok 2009 and references therein). I take it that the unexpected use of indefinite articles in AmNo arises when speakers fail to inhibit the grammatical representation that would be used in English (see Amaral and Roeper 2014; Seton and Schmid 2016 and references therein). This account is compatible with the fact that the origin of the predicate noun (English versus Norwegian) is not significant, as shown in Sect. 5.2. Assuming the Borer-Chomsky Conjecture (see Sect. 5.1), an account based on syntactic borrowing into the AmNo I-language would raise the question of why syntactic borrowing is dissociated from lexical borrowing.

It can be noted that attrition, in the present case and under the present analysis, does not really involve loss but instead arises from difficulties in accessing the relevant grammatical structure (Seton and Schmid 2016, 345).Footnote 57 Furthermore, note that the proposal made here bears some resemblance to what Eide and Hjelde (2015) propose for the (occasional) lack of V2 in a case study of an AmNo speaker.

5.4.2 A comparison with American Danish

At this point, comparing AmNo with American Danish (AmDa) is interesting; a relevant study is that of Heegård Petersen (2018).Footnote 58 Danish as spoken in Denmark (EurDa) mostly uses bare predicate nouns in the same way as EurNo. The reason why AmDa is relevant in the context of attrition is that Heegård Petersen’s (2018) AmDa data set, in contrast to the AmNo data presented in Sect. 3, includes a number of first-generation immigrants (Heegård Petersen 2018, 54). Unexpected linguistic behaviour in first-generation immigrants is most naturally interpreted as attrition, as attrition is defined as change during the lifetime of a speaker.Footnote 59 If the distribution of the indefinite article in first-generation AmDa speakers is similar to that found in AmNo (and different from EurDa), it suggests that attrition of this feature has happened in a closely related variety. This makes an attrition analysis seem plausible for AmNo, too.

In AmDa, the overall frequency of the indefinite article in predicate constructions (in the semantic classes ‘profession and social status’) is quite similar to that found in AmNo (and different from that found in EurDa): Heegård Petersen (2018, 57) reports a proportion of 85% bare nouns (\(n = 214\)) versus 15% nouns with an indefinite article (\(n = 36\)).Footnote 60 The figures for AmNo were 86.4% versus 13.6% (see Table 2); this is not significantly different from AmDa (Fisher Exact test, p = 0.888). Importantly, Heegård Petersen (2018, 58, n. 15) observes that there is no significant difference between first-generation immigrants from Denmark and later generations in terms of their use of the indefinite article in predicate constructions. This is easily compatible with an attrition account because attrition, in contrast to divergent attainment, can be expected to affect both first- and later generations of immigrants.

AmDa shows resemblance to AmNo also at the level of individual speakers: there are not many speakers who use the indefinite article consistently. Fourteen speakers use the relevant predicate constructions 4 times or more; Heegård Petersen (2018, 64) shows that 7 of these speakers always use bare nouns, 5 have a mixed pattern, and only two of them always use the indefinite article.

Admittedly, the similarities with AmDa do not, in isolation, provide conclusive evidence of which mechanism of change is at work in AmNo. However, the arguments for attrition in AmDa are weighty, and it would be unsurprising to see the same level of attrition of the same feature in AmNo.

6 Conclusion and outlook

This study has discussed the use of bare nouns versus nouns with the indefinite article in classifying predicate constructions in AmNo. I have shown that, similar to EurNo speakers, AmNo speakers mostly use bare nouns; however, in a subset of the data the indefinite article occurs to a non-negligible extent. I have argued that this English-like pattern is most likely to be caused by attrition rather than parametric change resulting from divergent attainment; furthermore, I have proposed that attrition in this case follows from problems with inhibiting the English grammar. The distribution of the indefinite article is generally characterised by intra-speaker variation; this is more typical of attrition than divergent attainment (Polinsky 2018, 28). Moreover, in parametric change, one could expect to see concomitant changes in bare type nouns (Borthen 2003) and in the representation of Number (e.g., Munn and Schmitt 2002, 2005); however, there are no clear indications of such changes.

The relative stability of bare predicate nouns, despite the intense contact with English, is interesting; as mentioned, it contrasts with certain other aspects of AmNo syntax (Taranrød 2011; Larsson and Johannessen 2015; Anderssen et al. 2018; van Baal 2018), and it raises the question of why bare nouns are apparently less prone to change. Among the factors that might have contributed are economy principles and age of acquisition. Economy principles are relevant because an extension of Number to new contexts, resulting in an extended use of the indefinite article, would be a change that adds a new feature to the structure of certain nominals. Although this is conceivable, it would presumably require very strong evidence in the input (it would violate the principle of Feature Economy, see Biberauer and Roberts 2017, 145). Support for the role of economy principles in heritage languages is given by Scontras et al. (2018), who argue that English-dominant heritage speakers of Spanish have developed a grammar in which agreement distinctions are encoded by fewer features than in homeland Spanish. An alternative hypothesis involving augmented structures with more features is rejected.Footnote 61 Age of acquisition is relevant because previous research has argued for a connection between features that are acquired late and divergent attainment (see Larsson and Johannessen 2015). Westergaard (2013) observes that children can make fine-grained syntactic and information-structural distinctions at a very early stage, and if this extends to the syntactic-semantic distinctions that underlie the distribution of the indefinite article, one could reasonably assume that this is fully acquired early on and is therefore more likely to remain stable.Footnote 62

Notes

A heritage language is defined in this paper as a language that is acquired by children in the home, but that is not the dominant language of the larger society (Rothman 2009, 156; Benmamoun et al. 2013). For further discussion, see (among many others) Montrul (2016, chap. 2) and Polinsky (2018, chap. 1).

The background details of many of the speakers included in this study can be found through the Corpus of American Norwegian Speech search interface, http://tekstlab.uio.no/glossa/html/?corpus=amerikanorsk.

E.g., Polinsky (2008, 41) defines the baseline of a heritage language as the language to which a heritage speaker was exposed as a child. This definition is not suitable for the present study, as I am interested in changes that might have happened over more than one generation (recall that today’s AmNo speakers are typically third- or fourth-generation immigrants).

Some transcribed samples are provided by Haugen (1953); moreover, some of Haugen’s recordings, as well as recordings made in 1931 by the Norwegian linguists Didrik Arup Seip and Ernst W. Selmer, have been made accessible by the Text Laboratory at the University of Oslo, http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/norskiamerika/english/recordings/seip-selmer.html. In the most recent version of the Corpus of American Nordic Speech, which was released after the data collection for this study was completed (see Sect. 3.1), some of these recordings have been included.

When the subject is non-human, the article is used even with classifying predicates (Halmøy 2001, 17). In the remainder of the paper, I abstract away from predicate constructions with non-human subjects.

A distinction similar to that between descriptive and classifying predicates is also found in other languages; cf. Munn and Schmitt (2005) and de Swart et al. (2007) on Germanic and Romance. A core point in Munn and Schmitt’s analysis is that only eventive predicate nouns can be bare. However, the proposal encounters some empirical problems when applied to Norwegian. For example, Munn and Schmitt (2005, 846) state that nouns denoting inherent categories and classes cannot be bare. This does not seem to be correct in Norwegian, in which the names of nationalities and nouns such as menneske ‘human’ and brunette ‘brown-haired female’ are typically bare. De Swart et al. (2007) relate the distinction to the semantic notion of capacity. This type of analysis seems to be a better fit for Norwegian data; I return to this point in Sect. 4.

Whilst the first emigrants left from Western Norway, emigration from Eastern Norway increased in the middle of the 19th century (Haugen 1953, 340), and today most American Norwegians speak a language that appears to descend from Eastern varieties (Johannessen and Salmons 2015, 10). However, some of the speakers represented in the data set state that their ancestors came from Trøndelag or Vestlandet.

Nouns with a modifying PP were included if the PP restricts the class denoted by the noun by objective criteria; an example would be medlem av NAF ‘member of the Norwegian Automobile Association’. In these cases we do not expect the indefinite article (Halmøy 2001, 19). In contexts of negation and questions, an indefinite article may generally be replaced by the quantifier noen ‘some’ (Faarlund et al. 1997, 221). This use of noen is not included in Table 1.

Other speakers use smågutt as a bare noun.

Norli (2017) proposes that EurNo might currently be undergoing a change; this is based on an observation that a number of present-day speakers seem to accept classifying predicate constructions with an indefinite article, as in English. Although this is an interesting finding, the implications for the present study are not clear. Norli’s study is mainly based on acceptability judgments and not spontaneous speech; therefore, his data are not directly comparable to the data discussed here. The study also includes speakers from different age groups, whilst I have restricted my queries to speakers over 50 years old.

More data has been added later and the search interface has been updated. Some of the new data are Swedish; therefore, the corpus now goes under the name Corpus of American Nordic Speech.

In collaboration with Yvonne van Baal and Alexander K. Lykke, I also conducted a translation task (English–Norwegian) in which one of the test sentences included a classifying predicate noun. Although the sample was very small, it can be noted that the speakers used the indefinite article to a greater extent in the translation task than in spontaneous speech. However, there is reason to believe that this was an artefact of the method, i.e., that the indefinite article was used under direct influence from the English prompt. (This could be understood as short-term, cross-linguistic structural priming, see Kootstra and Muysken 2017; van Gompel and Arai 2017; Fernándes et al. 2017; Jackson 2018). Illustratively, one of the speakers who produced the most classifying predicate constructions in spontaneous speech (\(n = 17\)), consistently using bare nouns, used the indefinite article in the translation task.

A few examples from CANS that did not match the search criteria because of mistagging were included. These examples were found by chance.

In a couple of cases I had to resort to more fine-grained rules to decide which predicate nouns to include. Under particular circumstances, if the subject is unknown to the addressee, the indefinite article may be used in EurNo even with predicates that are classifying rather than descriptive (Halmøy 2001, 17). I excluded one example which was clearly of this type. I also excluded a few examples in which a bare noun was echoing a bare noun used by a EurNo interviewer in an immediately preceding direct question.

To the extent that they occur, nominals in which both the article and the noun are English can be analysed as code switching. I am not aware of clear cases of an English indefinite article being combined with a Norwegian classifying predicate noun. For further discussion of language mixing in AmNo, see Grimstad et al. (2014) and Riksem (2017, 2018).

Each AmNo speaker in the data set has an individual code that is given in all cited linguistic examples. The code consists of the speaker’s home town, an index number and a combination of the letters u/g and m/k indicating the speaker’s age and gender: u = under 50, g = over 50; m = male, k = female. The code flom_MN_02gm thus identifies a speaker living in Flom, Minnesota, whose index number is 02 and who is a male over 50 years old.

As mentioned in footnote 9, the indefinite article is sometimes replaced by the quantifier noen ‘some’ in contexts of negation and questions in EurNo. To check if AmNo speakers use noen in this way in classifying predicate constructions (which would be unexpected from a EurNo point of view), I ran a search in CANS for the lemma noen followed by a singular noun (maximum interval: 4). I found no relevant occurrences of noen.

Eide and Hjelde’s (2015) study of V2 is based on speakers from the communities Coon Valley, Westby and Blair. As regards possessive constructions with a postnominal possessor, AmNo speakers actually use this construction even more frequently than EurNo adults; see Westergaard and Andersen (2015, 41).

For convenience the trees are based on Munn and Schmitt (2002), who take the indefinite article in English to spell out Num directly (in predicate contexts). In argument contexts, the indefinite article is often taken to be a D element (see e.g., Crisma 2015 for a recent discussion). For the purposes of this study, establishing the exact position of the indefinite article is not crucial; it could spell out Num directly or reflect the value of Num via Agreement. For an extensive discussion of nominals and the position of the indefinite article in Norwegian, see Julien (2005).

Using a plural predicate noun is also possible.

Present-day speakers of EurNo do not generally accept bare nouns in contexts directly corresponding to the Dutch example in (8).

I have asked native speakers of English in my environment for judgments.

Examples from Espinal (2010, 989); slightly adapted for clarification.

This is based on informal responses from 10 native speakers, half of whom allowed the cumulative reading in addition to the distributive reading. (Some of them stated that the cumulative reading was less obvious than the distributive reading, but it was nevertheless possible.) If the indefinite article is added (Vi har en konto i mange banker ‘We have an account in many banks’), most speakers seem to reject even a distributive reading; for these speakers the sentence is infelicitous unless it appears with either a bare noun or a bare indefinite plural.

Borthen (2003, 12) takes a different view; she states that bare nouns are specified as singular. Her argument comes from attributive adjectives: if a bare noun is modified by an adjective, the adjective cannot have plural inflection; it must be (what looks like) the singular. Accordingly, if an adjective, e.g., ny ‘new’, is inserted into a sentence such as (13a), the plural form nye is unacceptable (Her er det (*nye) avis nedi postkassen fra før); only ny, apparently singular masculine, is possible. However, I analyse this as default agreement, which occurs when “there is no controller with the necessary features” (Corbett 2006, 96). Corbett (2000, 185) observes that it is common for default number agreement to have the same form as the singular.

Donaldson (1993, 65) writes: “When an unqualified noun of profession or nationality occurs after the copula verbs bly ’to remain’, wees ’to be’ or word ’to become’, the indefinite article is occasionally omitted, but it is more usual to insert it and to do so is never wrong...”.

Number agreement in demonstratives is an exception.

One might hypothesise that gender pays a semantic contribution that has syntactic consequences. Broschart (2000, 258) argues that gender contributes to the establishment of classes to which objects can be assigned; such classes are relevant in classifying predicate constructions. A further step would be to assume that in languages without Gender, Number can have a similar function (see e.g., Biberauer 2017 on features that serve multiple purposes). Applying this logic to English, which does not have Gen, it would follow that that the Num feature cannot be freely omitted, as it serves a purpose beyond distinguishing singulars and plurals.

For example, memory and processing will typically be relevant in the context of attrition. Some factors, e.g., transfer, may, in principle, be relevant both for divergent attainment and attrition.

Relatedly, the notion that acquisition is ever “complete” has been challenged; see, e.g., Schmid and Köpke (2017).

Hasselmo presents acceptability judgments involving the borrowed nouns druggist and pilot and the non-borrowed nouns präst ‘priest’ and snickare ‘carpenter’.

King (2000, chap. 8) analyses the possibility of preposition stranding in Prince Edward Island French as a case of lexical borrowing with grammatical effects: French does not allow preposition stranding, but, according to King, Prince Edward Island French developed this property through the borrowing of English strandable prepositions. A problem with King’s account is that preposition stranding in Prince Edward Island French seems to be equally acceptable with all prepositions, borrowed and non-borrowed. King (2000) suggests that the stranding option has been extended from borrowed to non-borrowed prepositions, but she does not provide any evidence of a stage at which stranding correlated with English loans.

In compounds consisting of an English and a Norwegian part, the classification was based on the final element (i.e., the head). For example, skoleteacher ‘school teacher’ was counted as English; conversely, insurance-mann ‘insurance man’, was counted as Norwegian (the Norwegian spelling mann, chosen by the transcriber, reflects a Norwegian pronunciation /man/). In nouns whose written form is identical in Norwegian and English (e.g., student), I went by the speaker’s pronunciation; if the pronunciation had both English and Norwegian features, I particularly emphasised the realisation of /r/. In some cases, speakers use lexemes that exist in a more or less similar form in both languages, but differ in meaning, e.g., pensioner/pensjonær (English pensioner: ‘a recipient of pension, esp. the retirement pension’ (Thompson 1995); Norwegian pensjonær: ‘boarder’ (Kirkeby 2000).) In these cases, the decision was based on pronunciation; in other words, if a word such as pensioner/pensjonær was used with the English meaning but a Norwegian pronunciation, it was counted as Norwegian. Loan-translations, such as fiskemann ‘fisherman’, were treated as Norwegian.

Two of the nouns that I classified as English, guide and farmer, also exist as loan words in present-day EurNo (although farmer has a somewhat different meaning). One could argue that these nouns should not be counted as loan words because they might already have been known in Norway when the ancestors of the present-day AmNo speakers emigrated. I ran a separate test in which I classified guide and farmer as Norwegian, but there was still no significant difference between English and Norwegian nouns (p = 0.7891).

Heegård Petersen (2018, 58) makes similar observations for American Danish.

In the framework of Biberauer and Roberts (2017), analogical extensions are encompassed by the notion of Input Generalisation.

Recall that there are, on the other hand, a number of speakers who consistently use bare nouns.

As an alternative to the approaches to intra-speaker variation discussed in this section, Adger (2006, 2016) proposes an account based on the notion of combinatorial variability. An idea compatible with this approach could be that Num has been extended in the sense that an interpretable Num feature is always present, but that the “pool of variants (PoV)” (Adger’s term) includes nominal expressions both with and without a probing, uninterpretable Num feature. This would allow for a variant in which Num is present as an interpretable feature but is phonologically null. Even in the case of combinatorial variability, we do not expect the distribution of the variants to be completely free, but the determinants of the distribution can be very subtle and complex: Adger (2016) suggests that the choice of variant is made by a choice function which is external to the grammar and “... sensitive to all sorts of properties of the PoV: their phonology, their sociolinguistic connotations, whether they have been encountered recently, their frequency...”. The combinatorial-variability approach has wide empirical coverage, due to its flexibility, but testing it in the present context is difficult. Moreover, as I will show in next sections, there are indications that the Num feature in AmNo predicate constructions is not just null but completely absent.

A reviewer asks whether it can be established on independent grounds that the other speakers cited in this section control plural morphology, so that we can exclude the possibility that for example farmer in (20b, d) is a zero-marked plural. The most conclusive evidence would be utterances in which the relevant nouns are used by the same speakers with plural marking in non-predicate contexts, such as in (20a), but because there is only a limited amount of data per speaker, one cannot realistically expect to find relevant occurrences of all the nouns. The speakers sunburg_MN_03gm and coon_valley_WI_06gm are represented in CANS, and I have queried this corpus for relevant plurals. Sunburg_MN_03gm does not use the word pensjonist ‘retired person’ in the plural. Pensjonist is a masculine noun; for other nouns tagged as masculine, indefinite plurals, he mostly uses the ending /a/; this even extends to the English word car. It seems likely that he would have also used this ending for pensjonist, if it was intended as a plural. (I also looked through nouns tagged as masculine, indefinite singulars, to check if any of them should instead be interpreted as zero-marked, indefinite plurals, but I found no clear examples of this.) The speaker coon_valley_WI_06gm does not use the word snekker ‘carpenter’ in the plural, but his plural morphology mostly seems to be in place, and he uses the ending /e/ to mark the plural in the word mower, which bears morphological resemblance to snekker (they have the derivational suffix -er in common). The speakers sunburg_MN_16gm and sunburg_MN_20gk are currently not included in CANS. In the recordings from which the examples with farmer in (20b, d) are taken, they do not use this noun in the plural, or other masculine nouns with an -er derivational suffix, but in general they produce plural morphology as expected.

Interestingly, bare nouns with plural subjects seem to be even less restricted than in EurNo. The examples in (20) are not, or only marginally, acceptable to EurNo speakers whom I have consulted (cf. Sect. 4.1).

A reviewer remarks that apparent agreement mismatches can also be found in English, although their status is more dubious than in Norwegian (see Example (11) in Sect. 4.1, ??Many want to be a lawyer). In English, the indefinite article is present; therefore, absence of Num cannot explain the lack of agreement. The reviewer asks about the basis for distinguishing between the status of Norwegian Num-less predicate nouns with plural subjects and English examples such as (11) for AmNo speakers, the implication being that the AmNo examples might have a Num projection after all, perhaps under influence from English, although the article is missing. Excluding this possibility completely is difficult, but on the other hand, it would amount to saying that a syntactic structure that was already available in the heritage language (the Num-less structure) has been replaced by a less widely accepted pattern from the majority language that involves more features, but without any change in surface representation. This scenario appears less plausible; see Scontras et al. (2018), who argue for featural economy in heritage languages.

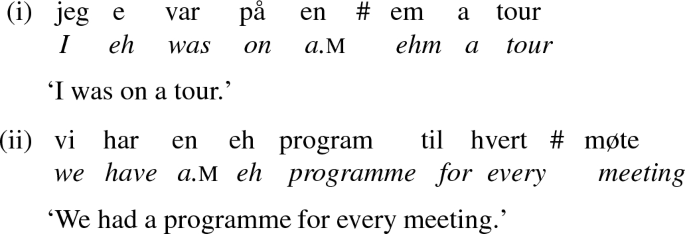

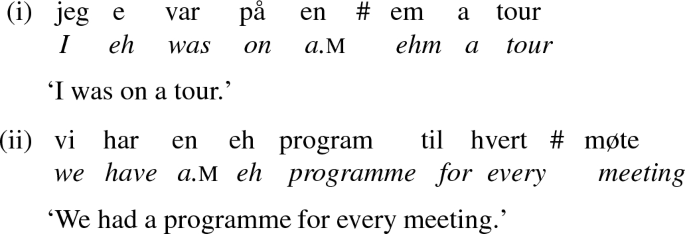

In this example the bare noun is English. According to the Missing Surface Inflection Hypothesis (Lardiere 2000; Prévost and White 2000), “missing” articles in the context of language mixing are not symptomatic of a missing functional category; rather, it is just the surface exponent which is missing, typically as a result of an avoidance strategy whereby the speaker chooses to omit the exponent rather than insert a potentially wrong form. Riksem (2017, 20ff) discusses the Missing Surface Inflection hypothesis in the context of AmNo and points out that it has inherent problems; one such problem is that it lacks restrictions. Moreover, upon closer inspection, it is unappealing to interpret the lack of an indefinite article in example (22) as an avoidance strategy for two reasons. First, there is no hesitation or prosodic breaks preceding the word passport, contrary to what one might expect if the speaker was uncertain. Second, if we look at other utterances in which the same speaker, portland_ND_02gk, does hesitate, she seems to be using a different strategy: she inserts the masculine form of the indefinite article, presumably as a default form, and then pauses to find the right word, which may or may not be masculine (pauses are marked with #):

In (i) she ends up using the English indefinite article after the pause; in (ii) she sticks with the Norwegian masculine article for a word that is neuter in EurNo (program). The main point here is that portland_ND_02gk does not seem to mind using the Norwegian indefinite article in cases in which she is not certain; therefore, the most obvious interpretation of the bare noun passport is that it is really a bare type noun, on a par with what we find in EurNo.

Furthermore, recall that sunburg_MN_16gm is one of the speakers who displays lack of agreement between a plural subject and a predicate noun (cf. example (20d)); this constitutes independent evidence that Num can be omitted.

For these exceptional speakers one could perhaps argue for a more limited parametric change whereby Num has become obligatory in predicate nouns only; such an outcome would be different from both English and EurNo.