Abstract

In this paper, we analyze the impact of immigration on Greek politics over the 2004–2012 period, exploiting panel data on 51 Greek regional units. We account for the potential endogenous clustering of migrants into more “tolerant” regions by using a shift-share-imputed instrument, based on their allocation in 1991. Overall, our results are consistent with the idea that immigration is positively associated with the vote share of extreme-right parties, though the effects appear to be stronger during the Greek fiscal crisis. This finding appears to be robust to alternative controls, sample restrictions and different estimation methods. We do not find supportive evidence for the conjecture that natives “vote with their feet,” i.e., move away from regions with high immigrant concentrations. We also find that the political success of the far-right comes at the expense of “Leftist” parties, thereby rejecting the idea that migration divides the society into different camps. Importantly, our analysis suggests that labor market concerns play a significant role in shaping native attitudes toward immigration.

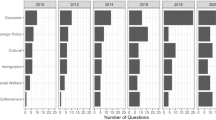

Source: Authors’ elaborations on data from the European Election Database

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2011, the top-5 sending countries were Albania, Bulgaria, Romania, Pakistan and Georgia (above 50% of total immigrants).

The evidence on the labor market consequences of immigration on the Greek labor market is scant. A recent study by Chletsos and Roupakias (2019), in the spirit of Borjas, suggests that there is significant positive association between migration and unemployment. On the other hand, Chassamboulli and Palivos (2013) employing a simulation-based approach argue that immigration exerts a favorable impact on the labor market outcomes of skilled laborers, while its impact on unskilled ones is ambiguous.

Evidence consistent with the idea that migration contributes to the political success of far-right parties is also reported in a recent published study by Edo et al. (2018) for the case of France.

A partial exception is Hangartner et al. (2017) who examine the impact of Syrian refugees on the “Golden Dawn” vote share in the Aegean Islands in 2015 by exploiting a difference-in-differences approach. However, since these authors focus on a particular group of migrants, they can estimate the response of natives along the intensive margin. In contrast, our study identifies the effects of general migration at extensive margin (considering both economic migrants and refugees), though the number of refugees is negligible in our sample, since we consider data before the outburst of the refugee crisis in 2015.

A complete list of regions is offered in the Appendix Table 11.

As shown in Schüller (2016), education plays a moderating role with respect to natives’ attitudes toward immigration.

In total, our dataset contains about 3,050,000 observations. We note, however, that there is still room for measurement error concerns because of undocumented migration.

Appendix figure A3 illustrates the vote shares of the Greek far-right parties across regions in the 2004 and 2012 elections.

We also note that an IV strategy can also attenuate the bias related to measurement error in the immigrant share variable, arising mainly due to undocumented migration.

To construct our instrument, we aggregate immigrants into 13 origin groups: Africa, Australia and New Zealand, Eastern Asia, Eastern Europe, Northern America, Northern Europe, South America, Southern Asia, Southern Europe, Western Asia, Western Europe and other countries. The full list of origin countries is reported in “Appendix.”

Following Ottaviano and Peri (2006), we have also experimented with distance from border and distance from the main getaways in Greece as instruments. However, these variables do not appear to explain much of the variation in the distribution of immigrants across regions, and thus, they are not included in the analysis.

We have also run regressions in which estimate whether different age cohorts of natives exhibit different attitudes toward migration, as expressed in the ballot box. To that aim, we have plugged into our model interactions between the share of pensioners or the share of younger adult voters and the immigrant share variable. The underlying assumption is that older cohorts might perceive migrants differently from the younger, mainly for two different reasons. First, senior voters might have been immigrants themselves during the emigration episodes that took place in the 1960’s and thus share common experiences with migrants residing currently in Greece. Second, they might be more favorably disposed toward migrants because they do not feel the labor market pressure in which their younger counterparts are exposed. Instead, old natives make extensive use of cheap caring services provided by immigrants. The results (not reported for brevity, available upon request) indicate our finding that immigration associated with increased support for far-right parties is mainly driven by voters aged between 18 and 64 years old.

We impute data for 1996 and 2006 from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses, respectively.

See, for instance, Eurostat’s statistics (available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset-=ilc-lvho02&lang=en) regarding the distribution of population by tenure status.

Data on crime rates were downloaded from the Hellenic Statistical Authority (available at: http://www.statistics.gr/).

What is more, this strategy enables us to test for overidentifying restrictions. Indeed, the Hansen J-statistic (not shown in Table 5) is well above the 5% threshold, thereby suggesting that our instruments are not correlated with the second-stage error term.

We compute for each of the variables indicated in the text the median value in 1991. Crime rate at NUTS-3 level is an exception, since it is available from 2011 onwards only.

We omit technical details on the construction of the index for brevity and refer the interested reader to Ottaviano and Peri (2006) for more information.

References

Alesina A, Baqir R, Easterly W (1999) Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 114(4):1243–1284

Alesina A, Glaser E, Sacerdote B (2001) Why doesn’t the United States have a European-style welfare state? Brook Pap Econ Act 2(2):187

Alesina A, Harnoss J, Rapoport H (2016) Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity. J Econ Growth 21(2):101–138

Allport GW (1954) The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Altonji JG, Card D (1991) The effects of immigration on the labor market outcomes of less-skilled natives. In: Abowd JM, Freeman RB (eds) Immigration, trade, and the labor market. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 201–234

Altonji JG, Elder TE, Taber CR (2005) Selection on observed and unobserved variables: assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. J Polit Econ 113(1):151–184

Aydemir A, Borjas GJ (2011) Attenuation bias in measuring the wage impact of immigration. J Labor Econ 29(1):69–112

Barone G, D’Ignazio A, de Blasio G, Naticchioni P (2016) Mr. Rossi, Mr. Hu and politics. The role of immigration in shaping natives’ voting behavior. J Public Econ 136:1–13

Bartel AP (1989) Where do the new US immigrants live? J Labor Econ 7(4):371–391

Bartik TJ (1991) Who benefits from state and local economic development policies?. Upjohn Press, Kalamazoo

Bauer TK, Lofstrom M, Zimmermann KF (2000) Immigration policy, assimilation of immigrants and natives’ sentiments towards immigrants: evidence from 12 OECD-countries. IZA

Becker SO, Fetzer T, Novy D (2017) Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis. Econ Policy 32(92):601–650

Bellini E, Ottaviano GI, Pinelli D, Prarolo G (2013) Cultural diversity and economic performance: evidence from European regions. In: Crescenzi R, Percoco M (eds) Geography, institutions and regional economic performance. Springer, Berlin, pp 121–141

Bellows J, Miguel E (2009) War and local collective action in Sierra Leone. J Public Econ 93(11–12):1144–1157

Bhatti Y, Danckert B, Hansen KM (2017) The context of voting: does neighborhood ethnic diversity affect turnout? Soc Forces 95(3):1127–1154

Bianchi M, Buonanno P, Pinotti P (2012) Do immigrants cause crime? J Eur Econ Assoc 10(6):1318–1347

Borjas GJ (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374

Borjas GJ (2006) Native internal migration and the labor market impact of immigration. J Hum Resour 41(2):221–258

Bratti M, Conti C (2018) The effect of immigration on innovation in Italy. Reg Stud 52(7):934–947

Brunner B, Kuhn A (2018) Immigration, cultural distance and natives’ attitudes towards immigrants: evidence from Swiss voting results. Kyklos 71(1):28–58

Card D (2001) Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration. J Labor Econ 19(1):22–64

Card D (2007) How immigration affects US cities (No. 0711). Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), Department of Economics, University College London

Card D, Dustmann C, Preston I (2012) Immigration, wages, and compositional amenities. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):78–119

Carlsson M, Dahl GB, Rooth D (2018) Backlash in attitudes after the election of extreme political parties. CESifo working paper series 7210. CESifo Group Munich

Chassamboulli A, Palivos T (2013) The impact of immigration on the employment and wages of native workers. J Macroecon 38:19–34

Chletsos M, Roupakias S (2019) Do immigrants compete with natives in the Greek labour market? Evidence from the skill-cell approach before and during the great recession. B.E. J Econ Anal Policy. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2018-0059

D’Amuri F, Peri G (2014) Immigration, jobs, and employment protection: evidence from Europe before and during the great recession. J Eur Econ Assoc 12(2):432–464

De Vries CE (2018) The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: changing patterns of party and electoral competition in the Netherlands and beyond. J Eur Public Policy 25(11):1541–1565

Dimakos IC, Tasiopoulou K (2003) Attitudes towards migrants: what do Greek students think about their immigrant classmates? Intercult Educ 14(3):307–316

Dustmann C, Preston I (2001) Attitudes to ethnic minorities, ethnic context and location decisions. Econ J 111(470):353–373

Edo A, Giesing Y, Öztunc J, Poutvaara P (2018) Immigration and electoral support for the far-left and the far-right. Eur Econ Rev 115:99–143

Faggio G, Overman H (2014) The effect of public sector employment on local labour markets. J Urban Econ 79:91–107

Gang I, Rivera-Batiz F, Yun MS (2002) Economic strain, ethnic concentration and attitudes towards foreigners in the European Union

Georgiadou V, Rori L, Roumanias C (2018) Mapping the European far right in the 21st century: a meso-level analysis. Elect Stud 54:103–115

Guriev S, Speciale B, Tuccio M (2016) How do regulated and unregulated labor markets respond to shocks? Evidence from immigrants during the great recession. CEPR discussion paper

Hainmueller J, Hiscox MJ (2007) Educated preferences: explaining attitudes toward immigration in Europe. Int Organ 61(2):399–442

Halla M, Wagner AF, Zweimüller J (2017) Immigration and voting for the far right. J Eur Econ Assoc 15(6):1341–1385

Hangartner D, Dinas E, Marbach M, Matakos K, Xefteris D (2017) Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? Am Polit Sci Rev 113:442–455

Harmon NA (2017) Immigration, ethnic diversity, and political outcomes: evidence from Denmark. Scand J Econ 120:1043–1074

Jaeger DA, Ruist J, Stuhler J (2018) Shift-share instruments and the impact of immigration (No. w24285). National Bureau of Economic Research

LaLonde RJ, Topel RH (1991) Labor market adjustments to increased immigration. In: Abowd JM, Freeman RB (eds) Immigration, trade, and the labor market. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 167–199

Luttmer EF (2001) Group loyalty and the taste for redistribution. J Polit Econ 109(3):500–528

Manacorda M, Manning A, Wadsworth J (2012) The impact of immigration on the structure of wages: theory and evidence from Britain. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):120–151

Mayda AM, Peri G, Steingress W (2018) DP12848 the political impact of immigration: evidence from the United States

Mendez I, Cutillas IM (2014) Has immigration affected Spanish presidential elections results? J Popul Econ 27(1):135–171

Minnesota Population Center (2018) Integrated public use microdata series, international: version 7.0 [dataset]. IPUMS, Minneapolis, MN. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.0

Mudde C (1996) The war of words defining the extreme right party family. West Eur Polit 19(2):225–248

Munshi K (2003) Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labor market. Q J Econ 118(2):549–599

Nunn N, Wantchekon L (2011) The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. Am Econ Rev 101(7):3221–3252

Ortega J, Verdugo G (2014) The impact of immigration on the French labor market: why so different? Labour Econ 29:14–27

Oswald AJ (1997) Thoughts on NAIRU. J Econ Perspect 11(4):227–228

Ottaviano GI, Peri G (2006) The economic value of cultural diversity: evidence from US cities. J Econ Geogr 6(1):9–44

Ottaviano GI, Peri G (2012) Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):152–197

Otto AH, Steinhardt MF (2014) Immigration and election outcomes—evidence from city districts in Hamburg. Reg Sci Urban Econ 45:67–79

Peri G, Sparber C (2009) Task specialization, immigration, and wages. Am Econ J Appl Econ 1(3):135–169

Pischke JS, Velling J (1997) Employment effects of immigration to Germany: an analysis based on local labor markets. Rev Econ Stat 79(4):594–604

Saiz A (2007) Immigration and housing rents in American cities. J Urban Econ 61(2):345–371

Scheve KF, Slaughter MJ (2001) Labor market competition and individual preferences over immigration policy. Rev Econ Stat 83(1):133–145

Schindler D, Westcott M (2017) Shocking racial attitudes: black G.I.s in Europe. CESifo working paper series 6723. CESifo Group Munich

Schüller S (2016) The effects of 9/11 on attitudes toward immigration and the moderating role of education. Kyklos 69(4):604–632

Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge JM (2015) What are we weighting for? J Hum Resour 50(2):301–316

Steinmayr A (2016) Exposure to refugees and voting for the far-right: (unexpected) results from Austria. IZA discussion papers 9790. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

Wagner D, Head K, Ries J (2002) Immigration and the Trade of Provinces. Scott J Polit Econ 49(5):507–525

Acknowledgements

We thank the Journal Editor, Professor Martin Andersson, and one anonymous referee for excellent comments that significantly improved the paper. Any remaining errors are, of course, the authors’ responsibility.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix: Variables: definitions and sources

Share of immigrants The ratio of foreign-born individuals over total working age (16–64) population. Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (International).

Population Logarithm of total population. Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (International).

Population density Logarithm of population per square kilometer. Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (International) and Wikipedia.

GDP per capita The ratio of Gross Domestic Product over total population. Source: Hellenic Statistical Authority.

Share of university graduates The ratio of natives with tertiary education over total working age (16–64) population.

Share of women The ratio of native women over total working age (16–64) population.

Share of pensioners The ratio of pension receivers over adult population.

Unemployment The proportion of unemployed natives (16–64) in total labor force.

Voter turnout The total number of votes cast divided by the number of eligible voters. Source: European Election Database.

Crime rate Reported crimes over the total population. Source: Hellenic Statistical Authority.

Election outcomes The vote share for each party. Source: European Election Database (Table 11).

Countries included in the construction of the shift-share instrument and fractionalization index

Integrated Public Use Microdata Series-International and United Nations (2015), Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin.

Origin countries Afghanistan, Africa, Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Armenia, Asia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Canada, Central African Republic, Central/South America and Caribbean, Chile, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czech Republic/Czechoslovakia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Denmark, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Libya, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway Oceania, Pakistan, Palestinian Territories, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Russia/USSR, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Slovakia, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Sudan, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, the UK, the USA, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Yugoslavia, Zambia, Zimbabwe (Fig. 3).