Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore associations between school principals’ self-efficacy for instructional leadership, their perceptions of work-related demands and resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to leave the principal position (quit). Four hundred and forty-seven principals in elementary school and high school participated in a survey study. Data were analyzed by means of confirmatory factor analyses and SEM analyses. Self-efficacy for instructional leadership was negatively associated with the perception of all job demands and positively associated with the perception of all job resources in the study. In the SEM analysis, the associations between (a) self-efficacy and (b) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were indirect, mediated through the perception of job demands and job resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and purpose

The role of the school principal has traditionally emphasized bureaucratic and management responsibilities, such as the responsibilities for the school economy, the facilities, teaching schedules, and personnel (Hallinger et al. 2018). During the last decades, greater emphasis has been placed on the principal’s responsibilities for the student learning, for developing goals and visions for the school, and for developing a stimulating learning environment, both for the students and the teachers (Point et al. 2008). Furthermore, The Norwegian Directorate for Primary and Secondary Education (2015) states that, “By definition, a school leader is responsible for everything that happens within the school” (p. 3), and “The principal is responsible for the pupils’ learning outcomes and learning environment and for ensuring good learning processes in the school” (p. 6).

The new leadership role has led to a greater accentuation on instructional leadership and leadership for learning. Moreover, it clarifies and strengthens the principal’s responsibility for the outcomes of the education. This responsibility is further underlined by the accountability philosophy that has become applicable in Norwegian school. The new leadership role therefore requires leadership skills that traditionally has not been heavily emphasized. The current role of the school principal, with a strong emphasis on instructional leadership, may therefore be perceived as challenging, stimulating and motivating, but also as stressful and exhausting.

Those aspects of the work or the work environment that may be stressful are often termed job demands, whereas aspects of the work or the work environment that may be stimulating and motivating are termed job resources. Possible impacts of job demands and job resources on stress and motivation are elaborated in the job demands–resources (JD–R) model (Bakker and Demerouti 2006; Demerouti et al. 2001).

One purpose of this study was to explore how self-efficacy for instructional leadership was associated with principals’ perceptions of job demands and job resources and how these constructs were associated with emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to leave the principal position (quit). Another purpose was to explore if, in a SEM model, the associations between (a) self-efficacy for instructional leadership and (b) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were, at least in part, mediated through the principals’ perceptions job demands and job resources.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is grounded in social cognitive theory (e.g., Bandura 1986, 1997). Bandura (1986) defines self-efficacy as “…peoples judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performance” (p. 391). Following this definition, self-efficacy refers to a person’s future-oriented beliefs about what he or she is able to do in different areas (Zimmerman and Cleary 2006). Self-efficacy may therefore be described as the answer to questions such as “Can I do it” and “How well can I do it” and can be measured at a problem-specific or at a domain-specific level (Bong and Skaalvik 2003).

According to Bandura (2006) self-efficacy affects how environmental opportunities and obstacles are perceived. Thus, self-efficacy beliefs determine if people think optimistically or pessimistically and influence peoples’ vulnerability to stress, worry, and depression. People with high self-efficacy tend to set challenging goals for themselves whereas people with low self-efficacy tend to dwell with their shortcomings (Bandura 1997). Based on social cognitive theory one may therefore expect that principals’ self-efficacy beliefs are positively associated with their perceptions of job resources and negatively associated with perceptions of job demands. Furthermore, social cognitive theory predicts that work-related self-efficacy are positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion.

Self-efficacy also affects peoples’ goals and aspirations, choice of tasks, how much effort they invest, and persistence when facing obstacles (Schunk and Meece 2006). People therefore tend to avoid situations and activities for which they have low self-efficacy. One may therefore expect work-related self-efficacy to be negatively associated with motivation to leave the job (quit).

Research on teachers verify that self-efficacy is positively related to job satisfaction and engagement and negatively related to burnout and motivation to leave the teaching profession (Brouwers and Tomic 2000; Collie et al. 2012; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2017).

2.1.1 Self-efficacy for instructional leadership

A common conceptualization of principal self-efficacy is that it is a judgment of the principal’s own “… capabilities to structure a particular course of action in order to produce desired outcomes in the school he or she leads” (Tschannen-Moran and Gareis 2004, p. 573). This is a broad definition that covers all aspects of the principal’s responsibilities. However, this study focused on principal self-efficacy for instructional leadership.

In an early attempt to define instructional leadership, Hallinger and Murphy (1985) discriminated between three dimensions of the construct: (a) defining the school mission (e.g., framing and communicating educational goals), (b) managing the instructional program (e.g., supervising and evaluating instruction), and (c) promoting a positive learning climate (e.g., motivating teachers). Hallinger (2010) later use the term “leadership for learning”. Robinson (2011) use the term “student centered leadership” and define it by characteristics overlapping those emphasized by Hallinger and Murphy (1985) and Hallinger (2010): (a) clarifying educational goals and expectations, (b) strategic resourcing, (c) planning and evaluating teaching and curriculum, (d) promoting teacher learning, and (e) ensuring an orderly and supportive environment.

Skaalvik (2020a) emphasized that the aim of instructional leadership should be to promote student learning and well-being. Instructional leadership was defined as a leadership practice that, through initiating reflections on and influencing the teachers’ goals, values, and practices, aim to improve instructional means and methods and to create a positive learning environment. Skaalvik (2020a) developed a 15-item “Self-efficacy for instructional leadership scale” measuring five dimensions: self-efficacy for a) developing educational goals and visions, (b) creating a collective culture characterized by shared goals and visions, (c) motivating teachers, (d) conducting classroom observations and guiding teachers, and (e) creating a positive and safe learning environment for the students. A study of 340 teachers revealed that self-efficacy for instructional leadership was predictive of lower levels of exhaustion, higher levels of engagement, and lower motivation to leave the position (Skaalvik 2020a).

2.2 The job demands–resources (JD–R) model

The JD–R model builds on an assumption that, in all occupations one may distinguish between two categories of work characteristics: job demands and job resources (Bakker and Demerouti 2006, 2014; Demerouti et al. 2001). Demerouti et al. (2001) define job demands as “those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort” (p. 501). Examples of job demands offered by Bakker and Demerouti (2006) are high work pressure, unfavorable physical environments, and emotionally demanding social interactions. Possible consequences of job demands are emotional exhaustion, burnout, and depressed mood. Job demands may not always have negative consequences and work-related challenges may even be stimulating. However, Bakker and Demerouti (2006) reminds us that job demands may turn into stressors when high and sustained effort are required to meet the demands.

Bakker and Demerouti (2006) define job resources as physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulate personal growth, learning, and development.

The JD–R model proposes that work-related demands and resources may lead to two relatively independent processes: a health impairment process and a motivational process. The health impairment process implies that job demands, through stress and increased effort, may lead to the depletion of energy, burnout, and health problems (Bakker and Demerouti 2006). A consequence of high and sustained effort or of lack of ability to meet the requirements may, according to the JD–R model, result in stress and emotional exhaustion. The motivational process implies that job resources may lead to increased job satisfaction and work engagement.

The JD–R model has been supported in several studies of employees in different occupations (for overviews, see Bakker and Demerouti 2006, 2014). For instance, in a study of Finnish teachers, Hakanen et al. (2006) found that job demands were associated with burnout and ill-health whereas job resources were associated with engagement. The study also indicated that job resources were associated with lower levels of burnout whereas burnout were associated with lower engagement. However, research exploring how job demands and job resources are associated with work-related self-efficacy, for instance school principals’ self-efficacy for instructional leadership, is lacking.

2.2.1 Job demands and job resources in the school principal profession

Some demands and resources may be common to several occupations. A job demand that may be common to several occupations is a heavy workload, and a job resource that may be common to several occupations is positive and supportive social relations at work. Nevertheless, Bakker and Demerouti (2006) reminds us that every occupation also may have its own specific demands and resources.

Research exploring principals’ perceptions of job demands and job resources is scarce. However, the available research indicates that principals experience a high time pressure or work overload, and that time pressure is predictive of burnout (Friedman 2002), emotional exhaustion (Skaalvik 2020b), and lower levels of job satisfaction (Skaalvik 2020b). Research on teachers has also shown time pressure to be associated with emotional exhaustion (e.g., Betoret and Artiga 2010). Research on principals also indicates that role ambiguity is associated with burnout (Gmelch and Torelli 1993) and a meta study by Schmidt et al. (2014) showed that role ambiguity is associated with depression. Friedman (2002) also found that principals experiencing demanding parents reported higher symptoms of burnout. Similar results are found in research on teachers (e.g., Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2012). Based on these studies, time pressure, role ambiguity, and demanding parents were included as job demands in the present study. Additionally, lack of shared values was included as a fourth demand because the communication of instructional values and goals have been strongly accentuated as a principal responsibility in recent years (Hallinger 2010; Robinson 2011). Therefore, the perception of a lack of shared values among the school staff may add to the stressors in the principal role.

A few studies also indicate that principals’ experiences of job resources are positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion. Federici and Skaalvik (2012), in a study of 1818 school principals, reported that perceived autonomy was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion. Research on teachers also reveals that perceived autonomy is associated with higher levels of job satisfaction (Koustelios et al. 2004). Skaalvik (2020b), in a SEM analysis, found that principals’ perception both of having competent teachers at school and of having opportunities for personal development at work were positively associated with job satisfaction. Autonomy, competent teachers, and opportunities for personal development were therefore included at job resources in the present study. Additionally, positive social relations with the staff were included as a fourth job resource, because research on teachers shows that positive social relations are associated with higher job satisfaction (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2017).

The present study builds on the assumption that job demands and resources may be conceptualized both objectively (as they can be perceived by an observer) and subjectively (as they are experienced by the employees, in this study by the principals). The present study explores subjective experiences of job demands and resources as do most studies of the JD–R model. As already argued, self-efficacy is assumed to affect how environmental opportunities and obstacles are perceived (see Sect. 2.1.). Hence, self-efficacy for instructional leadership was expected to influence principals’ perceptions of job demands and job resources in their daily work.

2.3 Emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion is conceptualized as a dimension of burnout that develops as a result of long-term work-related stress. It is characterized by low energy and chronic fatigue (Jennett et al. 2003; Maslach et al. 1996; Pines and Aronson 1988; Schwarzer et al. 2000). Empirical research indicates that emotional exhaustion results from stressful working conditions (Betoret and Artiga 2010; Fernet et al. 2012) but also from low self-efficacy (Brouwers and Tomic 2000; Evers et al. 2002; Friedman and Farber 1992; Saricam and Sakiz 2014). In a previous study of school principals, Skaalvik (2020b) found that both time pressure and demanding parents predicted emotional exhaustion. In turn, emotional exhaustion and burnout may result in low job satisfaction and intentions of leaving the job (Leung and Lee 2006). I therefore expected that emotional exhaustion among school principals would be positively associated with perceived job demands and negatively associated with perceived job resources. I also expected that emotional exhaustion would be predictive of lower job satisfaction and higher motivation to leave to principal position.

2.4 Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is commonly defined as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke 1976, p. 1304). It has both been studied as a global evaluation of one’s job situation and as evaluations of particular aspects of the job (Baeriswyl et al. 2016). Studies show that job satisfaction is associated with positive and supporting social relations at work, whereas it is negatively related to emotional exhaustion (e.g., Baeriswyl et al. 2016). Job satisfaction has also been shown to be associated with various organizational and individual outcomes. For example, high levels of job satisfaction are found to be associated with lower intentions of leaving one’s job (Fried et al. 2008; Hellman 1997; Ingersoll 2001; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2011). Previous studies of teachers also show that job satisfaction is associated with enthusiasm (Chen 2007). In this study, I was interested in an overall measure of the construct and how such a measure was associated with self-efficacy for instructional leadership as well as principals’ perceptions of job demands and job resources.

2.5 The present study

One purpose of this study was to explore how principal self-efficacy for instructional leadership was associated with their perception of four potential job demands and four potential job resources. A second purpose was to explore how self-efficacy, perceived job demands and perceived job resources were associated with emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. A third purpose was to explore if, in a SEM model, the associations between (a) self-efficacy for instructional leadership and (b) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were, at least in part, mediated through the principals’ perception of job demands and job resources.

As noted above, the potential job demands included in the study were time pressure, demanding parents, role ambiguity, and lack of shared goals and values among the teaching staff. The potential job resources included in the study were autonomy, competent teachers, positive social relations with the staff, and opportunities for self-development.

Based on the literature review, the general expectations were:

-

(1)

That self-efficacy for instructional leadership would be negatively associated with perceived job demands, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to quit.

-

(2)

That self-efficacy for instructional leadership would be positively associated with perceived job resources and job satisfaction.

-

(3)

That perceived job demands would be positively associated with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and negatively associated with job satisfaction.

-

(4)

That perceived job resources would be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit.

-

(5)

That emotional exhaustion would be negatively associated with job satisfaction and positively associated with motivation to quit.

-

(6)

That job satisfaction would be negatively associated with motivation to quit.

-

(7)

That, in a SEM analysis, the association between (a) self-efficacy for instructional leadership and (b) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit would be mediated through principals’ perception of job demands and job resources.

However, because job demands and job resources were assumed to be correlated, an open question was which job demands and job resources would be significantly related to emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit when controlled for each other in a SEM analysis.

3 Method

3.1 Participants and procedure

Participants in this study were 447 principals in elementary school and high school in six randomly selected counties in Norway. Data were collected using an electronic questionnaire. The sample consisted of 61% female principals and 39% male principals. Seven percent of the participants were between 30 and 40 years of age, 37% were between 41 and 50, 36% were between 51 and 60, and 20% were past 60 years of age. Forty-five percent of the principals were working in cities whereas 55% were working in schools in rural areas. Data were anonymized as soon as an SPSS file was developed.

3.2 Instruments

3.2.1 Self-efficacy for instructional leadership

Self-efficacy for instructional leadership was measured by means of a 15-item Self-efficacy for instructional leadership scale (Skaalvik 2020a). The scale consisted of five subscales: (a) development of goals and visions for the school (goals and visions), (b) development of a collective culture with shared goals and values (collective culture), (c) motivating teachers, (d) classroom observation and guidance of teachers (guiding teachers), and (e) creating a positive and safe learning environment for the students (learning environment). Examples of items are: “How certain are you that you can create engagement among the teachers?” (motivating teachers) and “How certain are you that you can develop a culture were all teachers work towards the same goals and values?” (collective culture). Responses were given on a 7-point scale from “Not certain at all” (1) to “Absolutely certain” (7). Cronbach’s alphas for the five subscales ranged from .72 to .90 and alpha for the total scale was .85.

3.2.2 Job demands

Job demands were measured by means of a 14-item scale measuring four dimensions of job demands in the principal functioning: time pressure, role ambiguity, lack of shared values, and demanding parents. The scale is a short version of a scale previously developed by Skaalvik (2020b). Examples of items are: “The workday of a principal never ends” (time pressure), “I often feel that I do not know what is expected of me as a principal” (role ambiguity), “It is difficult to reach an agreement on educational values at this school” (lack of shared values), and “Parents who complain about teaching occupy much of my time” (demanding parents). Responses were given on a six-point scale ranging from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s alphas for the four subscales ranged from .82 to .90 (see Table 1).

3.2.3 Job resources

Job resources were measured by means of a 14-item scale measuring four dimensions of job resources in the principal functioning: autonomy, positive social relations with the staff, competent teachers, and opportunities for personal development. The scale is a short version of a scale previously developed by Skaalvik (2020b). Examples of items are: “I have a great deal of decision latitude in my work” (autonomy), “I feel that my relationship with the teachers at the school is characterized by mutual respect and trust” (positive social relations), “The teachers at my school are very competent” (competent teachers), and “As principal, I learn something new every day” (opportunities for personal development). Responses were given on a six-point scale ranging from “Completely disagree” (1) to “Completely agree” (6). Cronbach’s alphas for the four subscales ranged from .71 to .85 (Table 1).

3.2.4 Emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion was measured by a previously tested six-item scale focusing on lacking energy and feeling tired from the work as a principal (Skaalvik 2020a). Examples of items are: “I feel exhausted from working as a principal” and “Working as a principal takes all my energy.” Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (6). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .91.

3.2.5 Job satisfaction

The principals’ overall job satisfaction was measured by means of a four-item job satisfaction scale (Skaalvik 2020b). Examples of items are: “I enjoy working as a principal” and “Working as a principal is extremely rewarding.” Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .91.

3.2.6 Motivation to leave the principal position

Motivation to leave the position as a principal was measured by a previously tested three item scale (Skaalvik 2020a). An example of an item is: “I often think of leaving the position as a principal.” Responses were given on a 6-point scale from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (6). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .92.

3.3 Data analysis

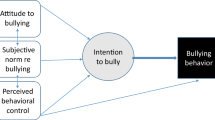

Firstly, zero order correlations among the scales included in the study were explored as well as statistical means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, skewness, and kurtosis. Secondly, confirmatory factor analyses with maximum likelihood extraction and varimax rotation were conducted of self-efficacy for instructional leadership as well as of job demands and job resources. Thirdly, associations between (a) self-efficacy for instructional leadership, (b) job demands and job resources, and (c) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were explored by means of structural equation modeling (SEM analyses). In order to test the theoretical assumption that the association between (a) self-efficacy and (b) emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were mediated through the perception of job demands and job resources, the SEM model was specified with a second order self-efficacy factor as an exogenous variable (see Fig. 1).

Final structural model of relations between self-efficacy for instructional leadership, job demands, job resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Significant standardized regression coefficients are reported. For simplicity, the indicators and the primary self-efficacy factors are not included in the figure

Model fit was indicated by well-established indices such as RMSEA, CFI, IFI, and TLI. For well-specified models, an RMSEA of .06 or less reflects a good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). For the CFI, IFI, and TLI indices, values greater than .90 are typically considered acceptable and values greater than .95 indicate a good fit to the data (Bollen 1989; Byrne 2001; Hu and Bentler 1999). Missing values were expected not to be systematic and were treated based on maximum likelihood (ML) estimation in the AMOS program (Byrne 2001). Compared to both listwise and pairwise deletion of missing data and to mean imputation, ML estimation will exhibit the least bias (Little and Rubin 1989; Muthén et al. 1987; Schafer 1997).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays zero order correlations between the five dimensions of self-efficacy for instructional leadership, the four job demands, the four job resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. The table also displays statistical means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, skewness, and kurtosis. An inspection of skewness and kurtosis indicates normal distribution and shape of the data.

The correlations among the five dimensions of self-efficacy for instructional leadership were moderate to strong, indicating that self-efficacy for instructional leadership, as measured in this study, may be treated as a one-dimensional construct. The validity is indicated by the finding that all dimensions of self-efficacy were positively associated with all job demands and negatively associated with all job resources. Also, all dimensions of self-efficacy correlated negatively with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and positively with job satisfaction.

The correlations between the four job demands and between the four job resources were weak to moderate. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the strongest of these correlations were found between autonomy and opportunities for personal development (r = .41) and between competent teachers and positive social relations (r = .44). The correlations between the job demands and the job resources were also weak and negative. However, two of these correlations stood out as higher than the rest—lack of shared values correlated − .43 with competent teachers and − .46 with positive social relations with the staff. The negative correlations between the job demands and the job resources provide a good indicator of the validity of the scales. Also, the low to moderate correlations indicate that the job demands, and the job resources included in this study should be treated as multidimensional constructs.

All job demands correlated positively with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and negatively with job satisfaction. In contrast, all job resources correlated negatively with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and positively with job satisfaction. Particularly high correlations were found between time pressure and emotional exhaustion (r = .60). Moreover, both opportunities for personal development and autonomy correlated highly with job satisfaction (r = .48 and .45, respectively).

4.2 Confirmatory factor analyses

4.2.1 Self-efficacy for instructional leadership

I first tested a measurement model of self-efficacy for instructional leadership. The model defined five primary factors (goals and visions, developing a collective culture, motivating teachers, observing and guiding teachers, and creating a positive and safe learning environment for the students) as indicators of a second order self-efficacy factor. The model had good fit to the data (χ2 [82, N = 447] = 227.440, p < .001, RMSEA = .063, IFI = .959, CFI = .959, TLI = .940). The five primary factors loaded strongly on the second order factor with standardized regression weights ranging from .644 to .925.

4.2.2 Job demands and job resources

Research based on the JD–R model typically analyze demands and resources as one-dimensional variables (e.g., Hakanen et al. 2006). However, because of the moderate correlations between the job demands and the job resources, two measurement models of these constructs were tested by means of confirmatory factor analysis. Model 1 defined eight correlated primary factors: four job demand factors and four job resource factors (see Method). The model had good fit to the data (χ2 [271, N = 447] = 438.331, p < .001, RMSEA = .037, IFI = .967, CFI = .966, TLI = .956) and all factor loadings were strong (Table 2). Model 2 defined two second order factors (job demands and job resources) indicated by the primary factors. This model also had good fit to the data (χ2 [290, N = 447] = 569.499, p < .001, RMSEA = .046, IFI = .944, CFI = .944, TLI = .932). The two models were compared using the Chi2-difference test (ΔChi2). The Chi2-difference test indicated that a model with primary factors fitted the data significantly better than a model with second order factors (ΔChi2 = 132.168, Δdf = 103, p < .001).

4.3 SEM analyses

Relations between self-efficacy for instructional leadership, job demands and job resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit were then explored by means of SEM analysis. Self-efficacy was, in the SEM model, represented by a second-order factor whereas job demands and job resources were represented by primary factors. I tested a model with self-efficacy as an exogenous variable. In the initial model, paths were included from self-efficacy to all job demand and job resource variables as well as to emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Paths were also included from all job demand and resource variables to emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Moreover, paths were included from job satisfaction to emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and from emotional exhaustion to motivation to quit. Thus, the model was designed to explore possible mediating effects of job demands and resources, but also unexpected direct associations between self-efficacy and exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Non-significant paths were then deleted one by one based on the p values, starting with the path with the highest p value. The final model (Fig. 1) had acceptable fit to the data (χ2 [1353, N = 447] = 2546.175, p < .001, RMSEA = .044, IFI = .914, CFI = .914, TLI = .905).

Self-efficacy was negatively associated with all job demands and positively associated with all job resources. However, in the SEM model there were no significant direct associations between self-efficacy for instructional leadership and emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, or motivation to quit.

Two of the potential job demands, demanding parents and time pressure, were significantly and positively associated with emotional exhaustion. Also, three of the job resources, autonomy, opportunities for personal development, and competent teachers, were significantly and positively associated with job satisfaction. None of the job demands were directly associated with job satisfaction and none of the job resources were associated with emotional exhaustion. However, three of the job resources were in the SEM model indirectly and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion, mediated through job satisfaction.

As expected, motivation to quit was positively associated with emotional exhaustion and negatively associated with job satisfaction. Additionally, two small positive associations were found, between lack of shared values and motivation to quit and between autonomy and motivation to quit.

As noted above, self-efficacy for instructional leadership was not directly associated with emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, or motivation to quit. However, self-efficacy was in the SEM model, through job demands and job resources, indirectly associated with all these variables. The indirect effects were − .47, .45, and − .41 on emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit, respectively.

5 Discussion

The zero order correlations (Table 1) verified the two first expectations: that self-efficacy for instructional leadership would be negatively associated with perceived job demands, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to quit, and positively associated with perceived job resources and job satisfaction. A reasonable interpretation of these findings is that they support an important assumption in social cognitive theory, that self-efficacy affects how environmental opportunities and obstacles are perceived and determine if people think optimistically or pessimistically (Bandura 1997). This assumption is also supported in a previous study by Osterman and Sullivan (1996), showing that principal self-efficacy influenced principals’ perception of the school environment. The associations between self-efficacy and job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to quit also support previous research (Collie et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2019; Skaalvik 2020a) and indicate that self-efficacy influences peoples’ vulnerability to stress. For instance, low self-efficacious principals, compared with high self-efficacious principals, experienced higher time pressure and stronger role ambiguity. They also reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion and lower levels of job satisfaction.

The zero order correlations also verified the third and the fourth expectations: that the principals’ perceptions of job demands would be positively associated with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit and negatively associated with job satisfaction, whereas their perceptions of job resources would be positively associated with job satisfaction and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and motivation to quit. These results support previous research exploring associations with job demands and job resources in educational occupations (Hakanen et al. 2006; Skaalvik 2020b). These results may be interpreted as supporting three key assumptions in the JD–R model, that job demands may lead to a health impairment process (indicated by emotional exhaustion in this study), that job resources may lead to a motivational process (indicated by job satisfaction in this study), and that these processes may have organizational consequences (indicated by motivation to quit in this study).

Furthermore, the zero order correlations also verified the fifth and the sixth expectations: that emotional exhaustion would be negatively associated with job satisfaction and positively associated with motivation to quit, and that job satisfaction would be negatively associated with motivation to quit. These results also support previous research results (Skaalvik 2020a; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2017).

Self-efficacy for instructional leadership was, in the SEM analysis, not directly related to emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, or motivation to quit. Thus, our seventh expectation, that these relations, in the SEM analysis, would be indirect and mediated through the perception of job demands and resources was supported. These findings strongly support the notion in social cognitive theory (Bandura 1997) that self-efficacy influences how people perceive the environment.Furthermore, we found only two significant, but small and close to zero regression coefficients showing direct relations between (a) job demands and resources and (b) motivation to quit. Thus, the associations between job demands and job resources on the one hand and motivation to quit on the other hand were almost entirely indirect, mediated through emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction. Taken together, a possible interpretation of the association between self-efficacy and motivation to quit is that if follows two main routes: one route from self-efficacy via lower levels of perceived job demands, lower levels of emotional exhaustion to lower motivation to quit, and another route from self-efficacy via higher levels of perceived job resources, higher job satisfaction to lower motivation to quit. Additionally, job satisfaction may decrease motivation to quit via decreased emotional exhaustion. Following these interpretations, a modification of the JD–R model including self-efficacy is displayed in Fig. 2.

It is important to note that the model displayed in Fig. 2 refers to perceived job demands and resources. Although real demands and resources may be found in all occupations, the terms “perceived job demands” and “perceived job resources” are used to emphasize that it is the subjective perceptions of demands and resources that may have motivational and health impairment consequences, and that the subjective experiences of job demands and job resources are influenced by self-efficacy. For instance, two principals may have equally many responsibilities and comparable administrative resources. However, due to differences in self-efficacy these principals may have quite different perceptions of demands and resources related to their functioning.

The model in Fig. 2 is a general model and includes unspecified self-efficacy and unspecified perceptions of demands and resources. The present study explored associations with self-efficacy for instructional leadership and cannot be generalized to other domains of principal self-efficacy without further research. Moreover, the SEM analysis in the present study clearly shows that the demands and resources included in the study are differently related to emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction. The far strongest predictor of emotional exhaustion was perceived time pressure or work overload, followed by demanding parents, whereas the strongest predictor of job satisfaction was perceived opportunity for personal development.

A general implication of these findings is that job demands and job resources should be studied not only as one-dimensional variables, as is often the case, but also as multidimensional constructs. Future research should, in longitudinal designs, explore which perceived demands and resources are most strongly associated with motivational and health-related outcomes. For instance, Watt and Richardson (2019) found, in a longitudinal study of 424 Australian teachers, that perceived job demands were predictive of burnout 7 years later. More research using longitudinal designs are needed to explore long term effects of self-efficacy and of job demands and resources, both in the teaching profession and among principals. Unfortunately, Watt and Richardson (2019) only included a single job demand, work overload, in their study.

More particularly, the findings in the present study indicate that, among school principals, time pressure is the job demand that has the most serious consequences for emotional exhaustion, and indirectly for motivation to quit. As noted in the introduction, during the last decades increased emphasis has been placed on the principal’s responsibilities for instructional leadership, including the motivation and guidance of teachers, the development of goals and visions for the school, and the development of a stimulating learning environment for the students. However, principals experiencing a high degree of time pressure may lack the energy that is needed to conduct instructional leadership. This may in turn lead to a concentration on routine tasks because instructional leadership may be more energy-intensive. This interpretation is in accordance with the introductory analyses of the new leadership role as requiring leadership skills that traditionally has not been heavily emphasized, that the role requires a broad range of skills, and that it may be perceived as overwhelming by some principals.

6 Limitations and need for future research

The study has several limitations. Although the sample was reasonably large (N = 447), it was marginal for testing the SEM model. Future research is needed with larger samples. Also, the study was designed as a cross-sectional survey and causal interpretations need to be verified in longitudinal studies. The model presented in Fig. 2 also needs to be tested in longitudinal studies. One assumption underlying the model is that self-efficacy affects the perception of job demands and resources. Although this assumption is based on social cognitive theory suggesting that self-efficacy influences how the environment is perceived, the association between self-efficacy and perceptions of environmental opportunities and obstacles are likely reciprocal. This calls for longitudinal studies. Moreover, although this study included four job resources and four job demands, more research is needed including other demands and resources. Future research should also explore the health impairment process and the motivational process by means of alternative variables to exhaustion and job satisfaction.

7 Conclusion

This study indicates that school principals’ perception of job demands and job resources are influenced by self-efficacy beliefs, and that the impact of self-efficacy on work-related emotion and motivation is mediated through perceived job demands and job resources. In future research these conclusions need to be tested in longitudinal designs. Job demands and job resources have in most previous research been analyzed as second order variables whereas this study strongly indicates that job demands and job resources in future research should also be analyzed as multidimensional constructs. Practically, the study indicates a need to reduce excessive demands, particularly the time pressure, in the principal positions in order for the school principal to devote time and energy for instructional leadership. Also, future research should explore if distributed leadership may reduce time pressure and emotional exhaustion experienced by school principals.

References

Baeriswyl, S., Krause, A., & Schwaninger, A. (2016). Emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in airport security officers—Work-family conflict as mediator in the job demands–resources model. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00663.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2006). The job demands—Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands—Resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide, volume III, work and wellbeing (pp. 37–64). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 1–43). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Betoret, F. D., & Artiga, A. G. (2010). Barriers perceived by teachers at work, coping strategies, self-efficacy and burnout. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13, 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600002316.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural models. Sociological Methods & Research, 17, 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004.

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382.

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modelling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Ass.

Chen, W. (2007). The structure of secondary school teacher job satisfaction and its relation with attrition and work enthusiasm. Chinese Education and Society, 40(2), 17–31.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029356.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499.

Evers, W. J. G., Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2002). Burnout and self-efficacy: A study on teachers’ beliefs when implementing an innovative educational system in the Netherlands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902158865.

Federici, R. A., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2012). Teacher and principal self-efficacy: Relations with autonomy and emotional exhaustion. In B. L. Shari (Ed.), Self-efficacy in school and community settings (pp. 125–150). New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013.

Fried, Y., Shirom, A., Gilboa, S., & Cooper, C. L. (2008). The mediating effects of job satisfaction and propensity to leave on role stress–job performance relationships: Combining meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 305–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013932.

Friedman, I. A. (2002). Burnout in school principals: Role related antecedents. Social Psychology of Education, 5, 229–251.

Friedman, I. A., & Farber, B. A. (1992). Professional self-concept as a predictor of teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Research, 86, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1992.9941824.

Gmelch, W. H, & Torelli, J. A. (1993). The association of role conflict and ambiguity with administrator stress and burnout. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association in Atlanta in April.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001.

Hallinger, P. (2010). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49, 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111116699.

Hallinger, P., Hosseingholizadeh, R., Hashemi, N., & Kouhsari, M. (2018). Do beliefs make a difference? Exploring how principal self-efficacy and instructional leadership impact teacher efficacy and commitment in Iran. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46, 800–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217700283.

Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. The Elementary School Journal, 86, 217–247. https://doi.org/10.1086/461445.

Hellman, C. M. (1997). Job satisfaction and intent to leave. Journal of Social Psychology, 137, 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549709595491.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Huang, S., Yin, H., & Lv, L. (2019). Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1543855.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 499–534. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312038003499.

Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Mesibov, G. B. (2003). Commitment to philosophy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000005996.19417.57.

Koustelios, A., Karabatzaki, D., & Kouisteliou, I. (2004). Autonomy and job satisfaction for a sample of Greek teachers. Psychological Reports, 95, 883–886. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.95.3.883-886.

Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: Differential predictability of the component of burnout. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 19, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600565476.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (1989). The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods and Research, 18, 292–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189018002004.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. Dunette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Mountain View, CA: CPP Inc.

Muthén, B., Kaplan, D., & Hollis, M. (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika, 52, 431–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294365.

Osterman, K., & Sullivan, S. (1996). New principals in an urban bureaucracy: A sense of efficacy. Journal of School Leadership, 6, 661–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268469600600605.

Pines, A. M., & Aronson, E. (1988). Career burnout. Causes and cures. New York: Free Press.

Point, B., Nusche, D., & Moorman, H. (2008). Improving school leadership—Policy and practice. Preliminary version. Paris: OECD, Education and Training Policy Division.

Robinson, V. (2011). Student-centered leadership. San Fransisco: Wiley.

Saricam, H., & Sakiz, H. (2014). Burnout and teachers’ self-efficacy among teachers working in special education in Turkey. Educational Studies, 40, 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.3.528.

Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall.

Schmidt, S., Roesler, U., Kusserow, T., & Rau, R. (2014). Uncertainty in the workplace: Examining role ambiguity and role conflict, and their link to depression—A meta-analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23, 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.711523.

Schunk, D. H., & Meece, J. L. (2006). Self-efficacy development in adolescence. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 71–115). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Schwarzer, R., Schmitz, G. S., & Tang, C. (2000). Teacher burnout in Hong Kong and Germany: A cross-cultural validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 13, 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800008549268.

Skaalvik, C. (2020a). School principal self-efficacy for instructional leadership: Relations with engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to quit. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09544-4.

Skaalvik, C. (2020b). Emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction among Norwegian school principals: Relations with perceived job demands and job resources. International Journal of Leadership in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1791964.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2012). Skolen som arbeidsplass. Trivsel, mestring og utfordringer [School as a workplace for teachers]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9363-9.

The Norwegian Directorate for Primary and Secondary Education. (2015). Leadership in Schools. What is required and expected of a school principal. https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/etter-og-videreutdanning/rektor/krav-og-forventninger-til-en-rektor/.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Gareis, C. R. (2004). Principals’ sense of efficacy. Assessing a promisong construct. Journal of Educational administration, 42(5), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230410554070.

Verbiest, E. (2011). Towards new instructional leadership. Effective professional learning of teachers and the role of the school leader. In T. Baráth & M. Szabó (Eds.), Does leadership matter? Implications for leadership development and the school as a learning organization (pp. 223–241). Budapest-Szeged: University of Szeged.

Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2019). Contextual influences on teacher in Augist 2019. Motivations, self-efficacy, and instructional & wellbeing outcomes. Paper presented in Symposium: “Teacher motivations: Antecedents and consequences for teachers and their students” at the EARLI conference in Aachen in August 2019.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Cleary, T. J. (2006). Adolescents’ develeopment of personal agency. The role of self-efficacy beliefs and self-regulatory skills. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolecents (pp. 45–69). Greenwich: Information Age.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in line with the ethical research guidelines and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) which serves as a national ethical research committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Scales and items (for response categories, see Sect. 3)

Appendix: Scales and items (for response categories, see Sect. 3)

1.1 Principal self-efficacy for instructional leadership scale

How certain are you that you can:

Develop goals

-

1.

¤¤ for the school.

-

2.

Develop clear goals and expectations for the teaching.

-

3.

Develop a strategic plan for achieving the goals.

Guide teachers

-

4.

Advise teachers about pedagogical matters.

-

5.

Observe teaching and provide helpful feedback.

-

6.

Use school based self-assessment to improve teaching and learning.

Create a positive and safe learning environment

-

7.

Create a safe school environment for students which is free from bullying.

-

8.

Ensure a learning environment in which students feel safe.

-

9.

Create a good teacher–student relationship.

Motivate teachers

-

10.

Create enthusiasm and engagement among the teachers.

-

11.

Motivate the teachers for teaching and instruction.

-

12.

Motivate the teachers to commit to the goals.

Develop a collective culture

-

13.

Develop a collective culture in which everyone works together to achieve shared goals.

-

14.

Develop a culture in which teachers support each other.

-

15.

Create a shared understanding of what constitutes good teaching.

Job demands

Time pressure

-

1.

The workday of a principal never ends.

-

2.

I am drowning in paperwork.

-

3.

I often feel overwhelmed by tasks.

-

4.

My workdays are hectic with few opportunities to take a break.

-

5.

To attend to all my responsibilities, I would need a larger administration.

-

6.

I have so many responsibilities that it is difficult to prioritize.

Frequent and unnecessary meetings

-

1.

I spend far too much time in meetings.

-

2.

I have to participate in too many unnecessary meetings.

Being detailed by the local school authority

-

1.

I often feel that I am being detailed by the local school authority.

-

2.

I get a lot of orders from the local school authority.

-

3.

I often get orders that I disagree with from local school authority.

Role ambiguity

-

1.

I find the principal role unclear.

-

2.

I often feel that I do not know what is expected of me as a principal.

Lack of shared values

-

1.

At this school there are very divided opinions on what is good teaching.

-

2.

It is difficult to reach an agreement on educational values at this school.

-

3.

Conflicts often arise between teachers at this school.

Worrying about single teachers

-

1.

Some of the teachers at this school show little engagement in teaching.

-

2.

Some of the teachers at this school do not teach well.

-

3.

Some of the teachers are always opposed to changes and developmental work.

Demanding parents

-

1.

Parents who complain about teaching occupy much of my time.

-

2.

There are always some parents who complain about the teachers.

-

3.

I experience parenting complaints as a burden.

Worrying about the school budget

-

1.

I often worry about the school’s finances.

-

2.

I often worry about exceeding the school budget.

-

3.

I often feel like I’m losing control of the school’s finances.

Sick leave among the teachers

-

1.

There is a lot of sick leave at this school.

-

2.

The extent of sick leave at this school reduces the quality of teaching.

-

3.

The extent of sick leave at this school leads to more work in the administration.

Job resources

Autonomy

-

1.

I have a great deal of decision latitude in my work.

-

2.

I have a great influence on what values we should emphasize at school.

-

3.

I have great opportunity to shape my own job.

Positive social relations

-

1.

I feel that my relationship with the teachers at the school is characterized by mutual respect and trust.

-

2.

I often get positive feedback from the teachers.

-

3.

I have a good relationship with all the staff at the school.

Supportive local school authority

-

1.

The local school authority supports the decisions I make.

-

2.

I get good advice and guidance from the local school authority.

Competent teachers

-

1.

The teachers at my school are very competent.

-

2.

The teachers at my school do a very good job.

-

3.

The teachers at this school are very committed to teaching.

Development-oriented teachers

-

1.

The teachers at this school always look for new solutions.

-

2.

The staff at this school are always looking for improvements.

-

3.

New ideas are welcomed by the staff of this school

Administrative resources

-

1.

This school has a well-developed administration.

-

2.

This school has good administrative resources

-

3.

I have skilled and motivated employees in the administration

Opportunities for personal development

-

1.

The work as school principal is instructive.

-

2.

As principal, I learn something new every day.

-

3.

As principal, I can work with what I am engaged in.

Job satisfaction

-

1.

I enjoy working as a school principal.

-

2.

I look forward to going to work every day.

-

3.

Working as a school principal is extremely rewarding.

-

4.

When I get up in the morning, I look forward to going to work.

Emotional exhaustion

-

1.

I feel worn out by my work

-

2.

I feel exhausted by working as a principal.

-

3.

The work as a school principal takes all my energy.

-

4.

I feel emotionally drained by the end of a school-day.

-

5.

At work I often feel I have no energy left.

-

6.

I increasingly feel dead tired at work.

Motivation to quit

-

1.

I wish I had a different job to being a school principal.

-

2.

If I could choose over again, I would not be a school principal.

-

3.

I often think of leaving the position as a school principal.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skaalvik, C. Self-efficacy for instructional leadership: relations with perceived job demands and job resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Soc Psychol Educ 23, 1343–1366 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09585-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09585-9