Abstract

The value of emission permits in environmental markets derives from the particular design features of the underlying cap-and-trade system. In this paper, we evaluate a model framework for the price dynamics of emission permits which accounts for these features in a reduced-form way. Based on permit futures and option data from the European Union Emissions Trading System, the world’s largest environmental market, we show that model variants which represent the design of the system most accurately provide the best fit to historical futures prices and achieve the best option pricing performance. Our results suggest that the specific design of cap-and-trade systems directly translates to the dynamic properties of emission permit prices, and that models tailored to environmental markets are the best choice for related pricing and risk management decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The G7 member states have agreed on this goal at the 41st G7 summit in June 2015. Subsequently, 195 countries worldwide have signed the Paris climate agreement, of which only the United States has announced the intention to withdraw.

By now, a double-digit number of cap-and-trade policies are in force all over the world, including systems in the European Union, in several states of Canada and the US, in South Korea, and in several provinces and cities in China.

Theory predicts that within a compliance period, the standard cost-of-carry relationship holds because permit spot and futures contracts can be traded without any frictions, see Hitzemann and Uhrig-Homburg (2018). Uhrig-Homburg and Wagner (2009) and Rittler (2012) show that this is also true empirically.

For \(R_t=0\), simply drop the last term \(e^{-r(T_m-{\overline{t}})^+}e^{\lambda _{m+1,t}}\) in (9) and all subsequent equations.

Unlike Grüll and Taschini (2009) and others, we exclude more sophisticated standard models, e.g., normal-inverse Gaussian (NIG) processes, from our analysis, since our focus is on the performance of reduced-form models within a pure Itô framework. We leave it open for future research to consider a reduced-form model framework for emission permit prices based on general Lévy processes.

The choice of this parametrization, which we label by CSCH due to its affinity to the hyperbolic cosecant, is mainly motivated by its simplicity and its favorable empirical behavior.

The ECX is the world’s largest carbon futures exchange and is operated by Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), http://www.theice.com.

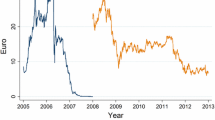

In Phase I from 2005 to 2007, it was forbidden to bank emission permits into the next compliance period, which led to a collapse of permit prices once the market realized that the economy was long of permits. In the ongoing Phase III from 2013 to 2020, the EU ETS undergoes a structural reform that addresses the large surplus of emission permits in the system.

The only non-generic point is the initialization procedure. Since the transition equation is non-stationary in all of its components, we initialize the unscented Kalman filter by using diffuse priors (see Harvey 1989, pp. 121–122). In particular, we employ the approach of Rosenberg (1973) to treat the initial state as fixed and unknown, and infer it by maximum likelihood estimation (see Durbin and Koopman 2001, pp. 117–188).

For the model parametrization \(z^{CH}_k\), the parameters \(\alpha _1,\ldots ,\alpha _m\) are set to 1 and not included into the numerical optimization.

We abbreviate by writing (CS)CH when a statement holds for both the CH and the CSCH parametrization.

Similar two-stage procedures are frequently applied for other model classes, see for example Broadie et al. (2007).

References

Bakshi, G., Cao, C., & Chen, Z. (1997). Empirical performance of alternative option pricing models. Journal of Finance, 52(5), 2003–2049.

Benz, E., & Trück, S. (2009). Modeling the price dynamics of CO\(_2\) emission allowances. Energy Economics, 31(1), 4–15.

Black, F. (1976). The pricing of commodity contracts. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 167–179.

Broadie, M., Chernov, M., & Johannes, M. (2007). Model specification and risk premia: Evidence from futures options. Journal of Finance, 62(3), 1453–1490.

Carmona, R., Fehr, M., & Hinz, J. (2009). Optimal stochastic control and carbon price formation. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 48(4), 2168–2190.

Carmona, R., Fehr, M., Hinz, J., & Porchet, A. (2010). Market design for emission trading schemes. SIAM Review, 52(3), 403–452.

Carmona, R., & Hinz, J. (2011). Risk-neutral models for emission allowance prices and option valuation. Management Science, 57(8), 1453–1468.

Carr, P., & Wu, L. (2009). Variance risk premiums. Review of Financial Studies, 22(3), 1311–1341.

Carr, P., & Wu, L. (2010). Stock options and credit default swaps: A joint framework for valuation and estimation. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 8(4), 409–449.

Casassus, J., & Collin-Dufresne, P. (2005). Stochastic convenience yield implied from commodity futures and interest rates. Journal of Finance, 60(5), 2283–2331.

Chesney, M., & Taschini, L. (2012). The endogenous price dynamics of emission allowances and an application to CO\(_2\) option pricing. Applied Mathematical Finance, 19(5), 447–475.

Christoffersen, P., Dorion, C., Jacobs, K., & Karoui, L. (2014). Nonlinear Kalman filtering in affine term structure models. Management Science, 60(9), 2248–2268.

Christoffersen, P., & Jacobs, K. (2004). The importance of the loss function in option valuation. Journal of Financial Economics, 72(2), 291–318.

Daskalakis, G., Psychoyios, D., & Markellos, R. N. (2009). Modeling CO\(_2\) emission allowance prices and derivatives: Evidence from the European trading scheme. Journal of Banking and Finance, 33(7), 1230–1241.

Dumas, B., Fleming, J., & Whaley, R. E. (1998). Implied volatility functions: Empirical tests. Journal of Finance, 53(6), 2059–2106.

Durbin, J., & Koopman, S. J. (2001). Time series analysis by state space methods. Oxford Statistical Science Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grüll, G., & Taschini, L. (2009). A comparison of reduced-form permit price models and their empirical performances. Working paper.

Harvey, A. C. (1989). Forecasting, structural time series models and the Kalman filter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hitzemann, S., & Uhrig-Homburg, M. (2018). Equilibrium price dynamics of emission permits. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 53(4), 1653–1678.

Kalman, R. E. (1960). A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. Journal of Basic Engineering, 82, 35–45.

Karatzas, I., & Shreve, S. E. (1991). Brownian motion and stochastic calculus. Berlin: Springer.

Paolella, M. S., & Taschini, L. (2008). An econometric analysis of emission allowance prices. Journal of Banking and Finance, 32(10), 2022–2032.

Rittler, D. (2012). Price discovery and volatility spillovers in the European Union emissions trading scheme: A high-frequency analysis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 36(3), 774–785.

Rosenberg, B. (1973). Random coefficients models. The analysis of a cross section of time series by stochastically convergent parameter regression. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 2(4), 399–428.

Schwartz, E. S. (1997). The stochastic behavior of commodity prices: Implications for valuation and hedging. Journal of Finance, 52(3), 923–973.

Schwartz, E. S., & Smith, J. E. (2000). Short-term variations and long-term dynamics in commodity prices. Management Science, 46(7), 893–911.

Seifert, J., Uhrig-Homburg, M., & Wagner, M. (2008). Dynamic behavior of CO\(_2\) spot prices. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 56(2), 180–194.

Trolle, A. B., & Schwartz, E. S. (2009). Unspanned stochastic volatility and the pricing of commodity derivatives. Review of Financial Studies, 22(11), 4423–4461.

Trolle, A. B., & Schwartz, E. S. (2010). Variance risk premia in energy commodities. Journal of Derivatives, 17(3), 15–32.

Uhrig-Homburg, M., & Wagner, M. (2009). Futures price dynamics of CO\(_2\) emission allowances: An empirical analysis of the trial period. Journal of Derivatives, 17(2), 73–88.

van der Merwe, R., & Wan, E. A. (2001). The square-root unscented Kalman filter for state and parameter-estimation. In IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing.

Wagner, M.W. (2007). CO \(_2\)-Emissionszertifikate—Preismodellierung und Derivatebewertung. Ph.D. thesis, University of Karlsruhe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank René Carmona, Martin Hain, Juri Hinz, Rüdiger Kiesel, Brenda López Cabrera, Marcel Prokopczuk, Claus Schmitt, Philipp Schuster, Nils Unger, as well as participants of the 2012 Financial Management Association Annual Meeting, 2013 EnergyFinance Conference, 2014 Institute of Mathematical Statistics Annual Meeting and Australian Statistical Conference, and seminar participants at Humboldt University Berlin for valuable discussions and helpful comments and suggestions. Financial support by the Graduate School 895 “Information Management and Market Engineering” at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendices

Appendix A: Dynamics of risk-neutral shortage probabilities

We derive the dynamics of the risk-neutral shortage probabilities \(A_k\) in general and show that all emissions processes (3) satisfying a narrow-sense linear SDE after transformation by a strictly increasing function lead to the same class of dynamics given by (6). For notational ease we omit the k indicating the compliance period in this section.

Let \(D_{t}(x_{t,T};.)\) be the cumulative density function of \(x_{T}\) given \(x_{t,T}\) at time t. By definition, it follows

Applying Itô’s Lemma directly yields

where \(g_{t}\) is the first derivative of \(G_{t}\). Equation (28) describes the general dynamics of the risk-neutral shortage probabilities.

Aiming at simple dynamics of \(A_t\), we assume that \(x_{t,T}\) can be transformed by a strictly increasing function \(\upsilon \) in such a way that \(\upsilon (x_{t,T})\) follows a linear SDE in the narrow sense, i.e.,

where \(a_1:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) and \(a_2:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) are continuous, bounded functions and \(b:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) is continuous and square-integrable. This especially covers a geometric Brownian motion as proposed by Carmona and Hinz (2011) or the case that \(\ln {x_{t,T}}\) follows an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process \(d\ln {x_{t,T}}=\kappa (\mu (t)-\ln {x_{t,T}}) dt+\sigma (t) dW_t\). Given \(x_{t,T}\), we can write \(\upsilon (x_{T})\) explicitly as

see Karatzas and Shreve (1991), pp. 360–361. Particularly, \(\upsilon (x_{T})\) is normally distributed with mean

and standard deviation

It follows that the cumulative density function is given by

and we obtain

Inserting into (28) yields

for the risk-neutral shortage probability. Now observe that the dynamics of \(\upsilon (x_{t,T})\) is also given by

applying Itô’s Lemma to (3). Comparing this to (29) yields

and we can write (35) as

with \(c(t)=e^{\int _t^T a_1(s)ds}b(t)\). Carmona and Hinz (2011) show that for every continuous function \(z:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) satisfying

there exists a square-integrable continuous function \(c:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) fulfilling \(\frac{c^2(t)}{\int _t^T c^2(s)ds}=z(t)\). Therefore we can construct every continuous function z satisfying (39) by the choice \(a_1(t)=0\) and \(b(t)=c(t)\). The other way round, \(c(t)=e^{\int _t^T a_1(s)ds}b(t)\) is a square-integrable continuous and positive function by the properties of \(a_1\) and b, and it follows that \(z(t)=\frac{c^2(t)}{\int _t^T c^2(s)ds}\) is positive and continuous and satisfies (39), see Carmona and Hinz (2011).

Altogether, for all dynamics of \(x_{t,T}\) for which a strictly increasing function \(\upsilon \) exists such that \(\upsilon (x_{t,T})\) follows a narrow-sense linear SDE (29), the class of possible dynamics for \(A_t\) is completely characterized by (6), with a continuous function \(z:(0,T)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) satisfying (39). Particularly, all possible dynamics for \(A_t\) in this class can be obtained by choosing an arithmetic Brownian motion (4) for the expected cumulative emissions process \(x_{t,T}\).

Appendix B: Evaluation of option pricing formulas

To calculate theoretical option prices within our reduced-form model framework, Eq. (14) requires the numerical evaluation of an \(m+1\)-dimensional integral. While this is straightforward in the one-dimensional case (\(m=0\)), the following transformations may help to improve computational efficiency for models with more price components. We demonstrate these transformations for the case of \(m=1\) and an additional component \(R_t\) as well as for \(m=2\) and \(R_t=0\).

In both cases, we decompose the bivariate normal distribution as proposed by Carmona and Hinz (2011) by defining

and we can write the integral in (14) as

for the case \(m=1\) with an additional component \(R_t\) or as

for \(m=2\) and \(R_t=0\).

Defining \(K^*(x_1)=K-e^{-r(T_1-{\overline{t}})}\Phi (x_1)p_1\), we note that the inner integral in (41) can completely be settled analytically according to

with

For (42), Carmona and Hinz (2011) show that numerical integration of the inner integral is only necessary if \(0<K^*(x_1)<e^{-r(T_2-{\overline{t}})}p_2\) since outside this interval we have

It is straightforward again to evaluate the outer integral of (41) and (42) once the inner integral is calculated.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hitzemann, S., Uhrig-Homburg, M. Empirical performance of reduced-form models for emission permit prices. Rev Deriv Res 22, 389–418 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11147-018-09152-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11147-018-09152-7