Abstract

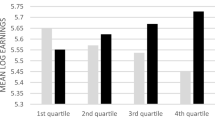

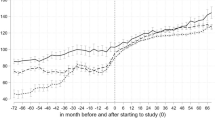

Research consistently shows that higher-education participation has positive impacts on individual outcomes. However, few studies explicitly consider differences in these impacts by socio-economic background (SEB), and those which do fail to examine graduate trajectories over the long run, non-labor outcomes and relative returns. We address these knowledge gaps by investigating the short- and long-term socio-economic trajectories of Australian university graduates from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds across multiple domains. We use high-quality longitudinal data from two sources: the Australian Longitudinal Census Dataset and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey. Low-SEB graduates experienced short-term post-graduation disadvantage in employment and occupational status, but not wages. They also experienced lower job and financial security up to 5 years post-graduation. Despite this, low-SEB graduates benefited more from higher education in relative terms—that is, university education improves the situation of low-SEB individuals to a greater extent than it does for high-SEB individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These fixed-effect models are not to be confused with difference-in-difference models (Donald and Lang 2007). Difference-in-difference models compare the pre/post outcomes of a group of individuals exposed to a ‘treatment’ (in our case degree attainment) and a control group of individuals not exposed to the same ‘treatment’. Difference-in-difference models require additional assumptions. This includes the parallel trend assumption—namely that, in the absence of the treatment, differences in outcomes between the treatment and control groups would be constant over time.

References

ABS. (2006). Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2017a). Education and work, Australia, May 2017. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2017b). Census of population and housing: Understanding the Census and Census data, Australia, 2016 (2900.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2018a). Microdata: Australian Census longitudinal dataset, 2011-2016 (2080.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2018b). Information paper: Australian Census longitudinal dataset, methodology and quality assessment, 2011-2016 (2080.5). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2018c). Australian statistical geography standard (ASGS): Volume 5—Remoteness structure, July 2016 (1270.0.55.005). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

ABS. (2018d). Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016 (2033.0.55.001). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Allison, P. (2009). Fixed-effect regression models. London: Sage.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (1st ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Brand, J. E., & Xie, Y. (2010). Who benefits most from college? Evidence for negative selection in heterogeneous economic returns to higher education. American Sociological Review, 75(2), 273–302.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2007). Explaining change in social fluidity: Educational equalization and educational expansion in twentieth-Century Sweden. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1775–1810.

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In O. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 3A, pp. 1801–1863). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cassells, R., Duncan, A., Abello, A., D’Souza, G., & Nepal, B. (2012). Smart Australians: Education and Innovation in Australia. Melbourne: AMP.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Curran, P. J., Obeidat, K., & Losardo, D. (2010). Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. Journal of Cognition and Development, 11(2), 121–136.

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2008). Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. In S. H. James, R. F. Schoeni, G. A. Kaplan, & H. Pollack (Eds.), Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Daly, A., Lewis, P., Corliss, M., & Heaslip, T. (2015). The private rate of return to a university degree in Australia. Australian Journal of Education, 59(1), 97–112.

Desjardins, R., & Lee, J. (2016). Earnings and employment benefits of adult higher education in comparative perspective: Evidence based on the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC). Los Angeles: UCLA.

Donald, S. G., & Lang, K. (2007). Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.89.2.221.

Edwards, D., & Coates, H. (2011). Monitoring the pathways and outcomes of people from disadvantaged backgrounds and graduate groups. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 151–163.

Elder, G. H. J., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–22). New York: Kluwer.

Flaster, A. (2016). Kids, college, and capital: Parental financial support and college choice. Research in Higher Education, 59(8), 979–1020.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1996). Class analysis and the reorientation of class theory: The case of persisting differentials in educational attainment. British Journal of Sociology, 47(3), 481–505.

Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis. Boston: Pearson.

Hansen, M. N. (2001). Education and economic rewards: Variations by social-class origin and income measures. European Sociological Review, 17(3), 209–231.

Harvey, A., Burnheim, C., & Brett, M. (Eds.). (2016). Student equity in Australian higher education: Twenty-five years of a fair chance for all. Singapore: Springer.

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2016). Returns to education: The causal effects of education on earnings, health and smoking. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heckman, J. J., Humphries, J. E., & Veramendi, G. (2017). The non-market benefits of education and ability. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Hout, M. (1984). Status, autonomy, and training in occupational mobility. American Journal of Sociology, 89(6), 1379–1409.

Jackson, M., Goldthorpe, J. H., & Mills, C. (2005). Education, employers and class mobility. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 23, 3–33.

Jacob, M., Klein, M., & Iannelli, C. (2015). The impact of social origin on graduates’ early occupational destinations—An Anglo-German comparison. European Sociological Review, 31(4), 460–476.

Li, I. W., Mahuteau, S., Dockery, A. M., & Junankar, P. N. (2017). Equity in higher education and graduate labour market outcomes in Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 39(6), 625–641.

Lin, N. (1999). Social networks and status attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 467–487.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

Manly, C. A., Wells, R. S., & Kommers, S. (2019). Who are rural students? How definitions of rurality affect research on college completion. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09556-w.

OECD. (2017). Education at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: Centre for Educational Research and Innovation, OECD.

Oreopoulos, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1), 159–184.

Perales, F. (2019). Modeling the consequences of the transition to parenthood: Applications of panel regression methods. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519847528.

Richardson, S., Bennett, D., & Roberts, L. (2016). Investigating the relationship between equity and graduate outcomes in Australia. Perth: The National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education at Curtin University.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

Tieben, N. (2019). Non-completion, transfer, and dropout of traditional and non-traditional students in Germany. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09553-z.

Torche, F. (2011). Is a college degree still the great equalizer? Intergenerational mobility across levels of schooling in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 117(3), 763–807.

Toutkoushian, R. K., Shafiq, M. N., & Trivette, M. J. (2013). Accounting for risk of non-completion in private and social rates of return to higher education. Journal of Education Finance, 39(1), 73–95.

Triventi, M. (2013). The role of higher education stratification in the reproduction of social inequality in the labor market. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 32, 45–63.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Thomas, P. A., Liu, H., & Thomeer, M. B. (2014). Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 20–38.

Union, European. (2014). Education and training monitor, 2014. Brussels: European Commission.

Ware, J. E., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Watson, N., & Wooden, M. P. (2012). The HILDA survey: A case study in the design and development of a successful household panel survey. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 3(3), 369–381.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE) at Curtin University (Grant reference Number RES-51444/CTR-11202).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomaszewski, W., Perales, F., Xiang, N. et al. Beyond Graduation: Socio-economic Background and Post-university Outcomes of Australian Graduates. Res High Educ 62, 26–44 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09578-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09578-4