Abstract

Consumers are often uncertain about their product valuation before purchase. They may bear the uncertainty and purchase the product without deliberation. Alternatively, consumers can incur a deliberation cost to find out their true valuation and then make their purchase decision. This paper proposes that consumer deliberation about product valuation can be an endogenous mechanism to enable credible quality signaling. We demonstrate this point in a simple setup in which product quality influences the probability that the product has high valuation. We show that with endogenous deliberation there may exist a unique separating equilibrium in which the high-quality firm induces consumer deliberation by setting a high price whereas the low-quality firm prevents deliberation by charging a low price. Compared to the case of complete information, the price of the high-quality firm can be distorted upward to facilitate consumer deliberation, or distorted downward to avoid the low-quality firm’s imitation. In an extension we show that dissipative advertising can facilitate quality signaling. The high-quality firm can utilize advertising spending to avert imitation from the low-quality firm without distorting price downward, earning a higher profit than that without advertising. However, advertising mitigates the distortion at the expense of consumer surplus and social welfare.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Consider the following example. David is driving along A104 highway in Paris. It is 12:00 p.m. and David wants to grab some food. Luckily he locates a restaurant just outside the next exit of the highway. David walks into the restaurant to find out that the only lunch set left there costs 10 euros. At this price it is not much surprise that David orders the food with little contemplation. After all, a lunch set of this price is hardly a bad deal for David. Suppose instead the lunch set costs 40 euros. It may not be a no-brainer for David any more. With most likelihood he may then hesitate and start pondering his valuation for the lunch set. After some hesitation, David may finally realize that the lunch set is indeed a good deal despite its cost. It may also be possible that, after recollecting a few of his past unpleasant dining experiences in similar highway restaurants, David decides to walk away without taking the lunch set. It is the incentive to avoid this possible negative outcome from an impulse purchase that prompts David to think more about his valuation before purchase.

Similar situations happen frequently in many purchase scenarios such as grocery shopping, digital products, financial services, calling plans, etc. Before purchase consumers are often uncertain about their valuations. The valuation uncertainty can arise for either physical products or services, new or repeated purchases, and search or experience goods. For example, even for frequently purchased packaged goods (e.g., soft drinks), each time arriving at the retail shelf, consumers may not be immediately sure about their willingness to pay. Similarly, even though technical specifications of digital products (e.g., memory size) can be perfectly known, consumers may not be able to readily tell how much value they should assign to the technical attributes.

Consumers may choose to bear the valuation uncertainty and make an imperfectly informed purchase, or they can strive to become better informed of their valuation before making the purchase decision. They can retrieve preference cues from memory, reflect on personal needs, process relevant information, inspect product specifications, and forecast future consumptions. We call deliberation these pre-purchase information-gathering activities that can (partially) resolve the valuation uncertainty (Guo and Zhang 2012; Guo 2015). For instance, David can recall his past dining experiences in similar restaurants, contemplate his desire for delicate food, inspect features of the lunch set, talk with nearby customers, gauge the anticipated pleasure of eating the food versus the outside option (e.g., biscuits in his car), and thus get a better sense about how much he is (currently) willing to pay for the lunch set. These deliberation processes are normally costly because they consume time, cognitive resources, and/or physical efforts (Shugan 1980; Guo and Zhang 2012; Guo 2015).

Product valuations are typically influenced by product quality. For example, the likelihood that David turns out to like the lunch set after deliberation can be positively influenced by the food’s quality. Such positive dependence of consumer valuation on product quality is prevalent. In general a consumer is more likely to have higher value for a high-quality product than for a low-quality one. Yet firms (e.g., the restaurant) usually have private information about their product quality, which is not perfectly known to consumers. A high-quality firm would then desire to convey her quality information to consumers because this can increase the consumers’ willingness to pay. However, a low-quality firm has all the incentive to pretend to be the high-quality firm by mimicking the latter’s strategy. Consequently, in the absence of verifiability, it is hardly credible for a firm to directly persuade consumers that her product is of high quality. As a result, firms may resort to signaling devices such as price to indirectly communicate their quality information (e.g., Gerstner 1985; Tellis and Wernerfelt 1987).

In this paper we propose that consumer deliberation can be an endogenous mechanism to empower a high-quality firm to signal her quality solely through price. Our game-theoretical model consists of a representative consumer and a monopolist firm who produces a single product of two quality types. The consumer has either a high or a low valuation. The probability that the consumer has the high valuation is positively related to the product quality, which is known to the firm but not known to the consumer. Furthermore, the consumer is not ex ante informed of his true valuation, but can incur a deliberation cost to unveil the valuation. The consumer decides whether to deliberate and whether to purchase the product. The consumer’s deliberation decision is affected not only by the perceived product quality but also by the price. The firm sets the product price to maximize her profit. The firm can employ her pricing strategy to influence the consumer’s quality perception as well as his deliberation and purchase behaviors. As a consequence, the consumer can infer the product quality from the price, i.e., the perceived quality may be endogenously influenced by the posted price.

In our model, without the possibility of deliberation, price alone cannot be a credible quality signal. By contrast, our primary result reveals that endogenous consumer deliberation can yield quality signaling. The reason is twofold. First, it can be more favorable for a high-quality firm than for a low-quality firm to induce deliberation. Second, the consumer’s incentive to deliberate may increase with the perceived quality. As a result, the single-crossing property for different firm types to sustain credible signaling may emerge endogenously. We show that there exists a unique separating equilibrium under which the high-quality firm sets a high price to induce deliberation whereas the low-quality firm charges a low price to prevent deliberation. Furthermore, the high-quality firm’s signaling behavior may lead to either an upward or a downward distortion from her optimal price under complete information.

We also extend the basic model to examine the role of dissipative advertising. We find that the mere spending of advertising can complement pricing and facilitate the credible communication of product quality. In particular, in the presence of advertising spending, not only the parameter conditions for credible signaling become less stringent, the scope of separating equilibria is also widened (e.g., a separating equilibrium may exist under which the consumer always deliberates upon seeing the price of either firm type). In addition, dissipative advertising can permit the high-quality firm to signal her type without distorting her price downward, improving profitability albeit at the expense of consumer surplus and social welfare.

2 Related literature

Our research is related to studies that investigate the implications of consumer deliberation. Guo and Zhang (2012) endogenize firms’ product offering decisions and investigate how firms should utilize product line design to either induce or prevent consumer deliberation. An emerging stream of research shows that deliberation may lead to endogenous preference construction and reconcile a range of seemingly irrational phenomena such as the compromise effect, choice overload, the anchoring effect, and preference reversals (Guo 2015, 2016; Guo and Hong 2016).

The search literature typically considers situations where search is necessary for purchase and consumers may not be fully informed of product features (e.g., attribute, price) prior to search (e.g., Kuksov and Lin 2015).Footnote 1 The standard role of search is to make the searched product become a feasible purchase option, whereas information gathering about product quality/valuation is only peripheral. By contrast, deliberation represents cognitive and physical efforts of information retrieval/acquisition about product valuation at the point of purchase occasion (i.e., the “last-minute” of the purchase process) where consumers are fully informed of product features.

The extant literature investigates various firm decisions, notably price and advertising spending, as signaling instruments for product quality (e.g., Kihlstrom and Riordan 1984; Milgrom and Roberts 1986; Tirole 1988; Bagwell and Riordan 1991). Researchers have also explored other instruments to signal product quality, such as umbrella branding (Wernerfelt 1988) and product warranty (Moorthy and Srinivasan 1995; Balachander 2001; Soberman 2003). The credibility of these instruments is typically established through a variety of economic mechanisms that ensure the single-crossing property across quality types: cost differential, valuation heterogeneity, presence of informed consumers, repeat purchase, etc. In contrast to the literature, we intentionally consider a static model with constant costs and ex-ante homogenous consumers, thus including none of these standard quality-signaling mechanisms. This allows us to show that consumer deliberation can be a distinctive driving mechanism for quality signaling.

This research relates to several papers on the interaction between firm information provision and consumer information acquisition. In Bhardwaj et al. (2008) a firm can signal quality through selling format: firm-initiated or buyer-initiated information revelation. That is, whether the consumers engage in information collection is determined by the firm. By contrast, in our model it is the consumer who chooses whether to deliberate. Branco et al. (2016) show that firms may provide limited information to consumers in a setup where the consumers can sequentially decide how much information to acquire.Footnote 2Kuksov and Villas-Boas (2010) investigate how assortment size may influence the information value of consumer search. Mayzlin and Shin (2011) consider the possibility of signaling through pricing when consumers can incur a cost to search for preference information. They show that credible signaling does not arise even in the presence of consumer search. This is because in their model signaling and consumer search are perfect substitutes in resolving consumers’ valuation uncertainty such that, should firm pricing strategies reveal product quality to the consumers, search would become immaterial. By contrast, our setup considers two layers of uncertainty whereby, even if the uncertainty about quality can be eliminated through firm signaling, there still exists some uncertainty about product valuation that can be resolved through deliberation. We demonstrate that firms of different qualities may have different preferences over consumer deliberation. This would then constitute an endogenous mechanism for the emergence of the single-crossing property in credible signaling.

3 Model setup

We consider a signaling game between a monopolist firm and a representative consumer. The risk-neutral firm produces a single product and has private information about her product quality q∈{q L ,q H }, where 0≤q L <q H ≤1. We call the high- and the low-quality firm as type-H and type-L firm, respectively. The firm is of type H with prior probability ϕ∈(0,1), which is common knowledge.

The consumer can have either a high product valuation V H , or a low valuation V L . Without loss of generality, we set V H =1 and V L =0. The product quality, q∈{q L ,q H }, represents the probability that the consumer has the high valuation.Footnote 3 Although the valuation distribution for each quality type is common knowledge, the consumer does not ex ante know his true valuation. Similar setup of product quality can be seen in many studies (e.g., Schmalensee 1982; Wernerfelt 1988; Moorthy and Srinivasan 1995). The consumer has a one-unit demand for the product. Without loss of generality, we assume that the outside option is of value zero.

Following Guo and Zhang (2012), we allow the consumer to incur a deliberation cost c>0 to discover his true valuation before purchase.Footnote 4 The deliberation can involve various cognitive and physical processes that reduce valuation uncertainty, such as information retrieval/processing, introspection, retrospection, anticipation, and inspection.Footnote 5 The cost of deliberation can account for, for example, the disutility of engaging time and cognitive/physical efforts. If the consumer chooses to deliberate, his purchase decision is based on the realized valuation. If he decides not to deliberate, he makes the purchase decision without resolving the valuation uncertainty.

In our basic model the firm determines the product price and cannot credibly convey her product quality via other instruments. The production costs per unit of both quality types are the same and normalized to zero. As a result, the firm is always willing to provide the product no matter which type she is perceived to be. This assumption is intentionally made to rule out cost differential as a mechanism for quality signaling (e.g., Moorthy and Srinivasan 1995). Our assumption that there is only a single, ex-ante uninformed representative consumer also rules out consumer heterogeneity as a potential mechanism for quality signaling (e.g., Bagwell and Riordan 1991; Moorthy and Srinivasan 1995). In addition, to preclude repeat purchase as a possible signaling mechanism (e.g., Milgrom and Roberts 1986; Tirole 1988), we consider a one-period interaction between the firm and the consumer.

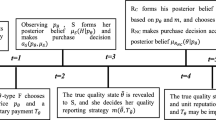

In sum, the signaling game proceeds as follows. First, the product quality is determined by nature and is revealed to the firm. Second, the firm sets the price p. In the third stage of the game, after observing p, the consumer decides whether to deliberate to find out his true valuation and then whether to purchase the product.

4 Equilibrium

The solution concept we adopt in this paper is the Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (Fudenberg and Tirole 1991). The consumer holds the common prior belief μ(⋅) on product quality, where μ(q H ) = ϕ and μ(q L )=1−ϕ. The consumer updates his belief according to the Bayes’ rule whenever applicable, and responds optimally to the price based on his posterior belief. In particular, after observing the price p, the consumer may update his prior belief into the posterior belief μ(⋅|p), based on the firm’s equilibrium pricing strategy. Furthermore, given the consumer’s posterior belief and optimal behavior, the firm determines the price to maximize her profit.

We restrict our attention to pure-strategy equilibria. Denote the equilibrium prices of type-H and type-L as p H and p L , respectively. There are two possible types of equilibria. The first type is separating equilibria in which p H ≠p L . In any separating equilibrium, according to the Bayes’ rule, the posterior equilibrium belief perfectly reveals the quality, i.e., μ(q H |p H )=1 and μ(q L |p L )=1. The second type is pooling equilibria in which p H = p L = p ∗. In any pooling equilibrium the posterior equilibrium belief on quality is not updated, i.e., μ(q H |p ∗) = μ(q H ) = ϕ.

It is well known that the arbitrariness of specifying out-of-equilibrium beliefs in Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium can lead to multiple equilibria. We adopt the intuitive criterion (Cho and Kreps 1987) as our equilibrium refinement to rule out equilibria that are driven by “unreasonable” out-of-equilibrium beliefs. The intuitive criterion requires that the consumer engage in certain kind of forward induction. If, by deviating to a price p, type-j firm is worse off under any possible belief, then the out-of-equilibrium belief should put zero probability on type j after the price p is observed.Footnote 6 This equilibrium refinement is typically adopted for signaling models (e.g., Srinivasan 1991; Desai and Srinivasan 1995; Simester 1995).

We first examine the consumer’s optimal deliberation and purchase decisions, conditional on any (updated) quality perception. We then derive the equilibrium outcome in the benchmark case when the quality is a priori known to the consumer. Finally we characterize the separating and the pooling equilibria in the case of incomplete quality information.

4.1 Optimal consumer behavior

Consider the consumer’s optimal behavior, given any posterior belief μ(⋅|p). Let the perceived product quality be \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} = E(q\,|\,\mu (\cdot |p)) = \mu (q_{H} | p) q_{H} + \mu (q_{L} | p) q_{L}\). Without deliberation, the consumer expects to have the high valuation with probability \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\). Hence his willingness to pay is \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} \cdot 1 + (1 - \bar {q}) \cdot 0 = \bar {q}\). The consumer buys the product if and only if \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} \ge p\). If instead the consumer chooses to deliberate, he purchases the product if and only if the realized valuation is high. His ex-ante expected payoff for deliberation is thus \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} (1 - p) - c\). As a result, the consumer deliberates if and only if \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} (1 - p) - c \ge 0\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q} (1 - p) - c > \bar {q} - p\). This can be rewritten as \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c < \bar {q} (1 - \bar {q})\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c / (1 - \bar {q}) < p \le 1 - c / \bar {q}\).

Deliberation is optimal if and only if the value of information exceeds the deliberation cost. The first condition, \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c < \bar {q} (1 - \bar {q})\), requires that the perceived quality \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\) cannot be too small or too large. This is because, when \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\) is close to 0 or 1, the consumer would have little uncertainty with regard to valuation and deliberation would be hardly desirable. Even if the valuation uncertainty is large enough, the price cannot be too low (i.e., \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p \le c / (1 - \bar {q})\)), because otherwise the consumer would simply purchase without deliberation. On the other hand, the price cannot be too high either (i.e., \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p > 1 - c / \bar {q}\)), because otherwise the consumer would opt for the outside option.

4.2 Equilibrium under complete information

Consider the benchmark case of complete information for product quality q j ∈{q L ,q H }. This will allow us to investigate how incomplete information may distort equilibrium prices and profits.

When c ≥ q j (1−q j ), the consumer never finds it optimal to deliberate. The firm would then simply charge a price equal to the consumer’s willingness to pay, earn an equilibrium profit π j = q j , and acquire all consumer surplus. When c<q j (1−q j ), the consumer purchases without deliberation provided p≤c/(1−q j ), and deliberates provided c/(1−q j )<p≤1−c/q j . The highest profit the firm can generate by preventing deliberation is c/(1−q j ), and the highest profit by inducing deliberation is (1−c/q j )⋅q j = q j −c. The firm compares these two alternative strategies to decide whether to impede or to prompt the consumer to deliberate.

As a result, when the deliberation cost is moderate, i.e., κ j ≤c<q j (1−q j ), where κ j ≡[1/q j (1−q j )+1/q j ]−1, the optimal price and profit are P j =π j = c/(1−q j ). In this case the firm would rather forestall deliberation by cutting the price to c/(1−q j ), which is lower than the consumer’s expected valuation of the product. The firm cannot appropriate all consumer surplus, i.e., the possibility of deliberation leaves the consumer an expected surplus of q j −c/(1−q j ). When the deliberation cost is small (i.e., c<κ j ), preventing deliberation becomes too costly and the firm would rather adopt the deliberation-inducing strategy by raising the price to P j =1−c/q j . In doing so the firm manages to secure all consumer surplus.

Figure 1a shows how the optimal price and the equilibrium profit vary non-monotonically with the deliberation cost c. The optimal price is first decreasing and then increasing, and has a discontinuous drop at the cut-off point κ j when the deliberation cost changes from the “small” range to the “moderate” range. This is because of the change of the firm’s strategy from inducing deliberation to preventing deliberation. The equilibrium profit is continuous and exhibits a “V-shaped” relationship with c. It is worth noting that, not only can the price and the profit rise with c, the consumer welfare can benefit from a higher deliberation cost as well. In particular, the consumer welfare jumps from zero to positive when the deliberation cost increases from below to above κ j . This is due to the “money left on the table” when the firm shifts to the deliberation-preventing strategy.

Figure 1b illustrates the impacts of product quality q j on the equilibrium outcome. The bottom panel demonstrates how the variation in c determines the equilibrium region. As q j rises from 0 to 1, the deliberation cost switches from falling into the “large” region to the “small” region, and then back to the “large” region again. Interestingly, as shown in the upper panel, even though the equilibrium profit always becomes larger as q j grows throughout [0, 1], the optimal price can decrease with a higher quality. This is because, when the quality becomes sufficiently large and hence the information value of deliberation is low, the firm may find it optimal to cut the price such that the consumer purchases without deliberation.

4.3 Separating equilibrium

We now investigate the case when the product quality is the firm’s private information and the high-quality firm can credibly signal her type through pricing. In any separating equilibrium, the equilibrium prices are different, i.e., p H ≠p L . There are four possible types of separating equilibria in this game, depending on whether the consumer chooses to deliberate upon seeing the equilibrium prices: (i) no deliberation, in which the consumer does not deliberate after observing either p H or p L ; (ii) deliberation on both, in which the consumer deliberates after seeing either p H or p L ; (iii) deliberation on p L , in which the consumer deliberates on p L but not on p H ; and (iv) deliberation on p H , in which the consumer deliberates on p H but not on p L . The following lemma shows that the first three types of separating equilibria do not exist.

Lemma 1

There exists no separating equilibrium with any of the following consumer behavior: (i) the consumer does not deliberate at all; (ii) the consumer deliberates on both p H and p L ; or (iii) the consumer deliberates on p L but not on p H .

Perhaps not surprisingly, the first two types of separating equilibria cannot be sustained. When consumer deliberation does not respond to the prices of different firm types, the firm with a lower price would always adopt the other type’s high-price strategy. Intuitively, the prices cannot credibly inform the consumer of the firm’s types unless the prices yield different consumer deliberation. The third type of separating equilibrium does not emerge either, because there does not exist a deliberation-preventing price p H for type-H firm that is both low enough to prevent type-L firm’s mimicking, while at the same time sufficiently high such that type-H firm is better off separating from type-L firm. Lemma 1 thus suggests that the only possible separating equilibrium is of the deliberation-on- p H type.

The non-existence of the deliberation-on- p L type of equilibrium can be generalized even when there are more than two types of product qualities. This result implies that, for any two quality types j and j ′ with \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}q_{j} < q_{j^{\prime }}\), there does not exist an equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates on the low-quality firm’s price p j but purchases without deliberation on the high-quality firm’s price \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{j^{\prime }}\). As a consequence, a firm of higher quality cannot pool with a firm of lower quality while separating from a middle type between them. Therefore, according to Lemma 1, the only possible types of equilibria are either full pooling equilibria, or semi-separating equilibria in which firms above a quality threshold collectively post a high price, while separating from firms below the threshold who pool to set a low price, and the consumer deliberates on the high price but purchases without deliberation on the low price. In other words, the equilibrium monotonic relationship between firm type and consumer deliberation implies the non-existence of countersignaling equilibrium (e.g., Feltovich et al. 2002; Mayzlin and Shin 2011).

We next investigate the existence of the deliberation-on- p H type of equilibrium. The following proposition fully characterizes this type of equilibrium outcome.

Proposition 1

There exists a separating equilibrium if and only if q H <1−q L (1−q L ) and κ L ≤c≤κ U .Footnote 7 The equilibrium prices are unique:

In equilibrium the consumer deliberates on p H and purchases without deliberation on p L . The equilibrium beliefs are μ(q H |p H )=μ(q L |p L )=1, and the out-of-equilibrium beliefs are μ(q L |p)=1, for all p≠p L or p H .

In the unique separating equilibrium type-L firm precludes consumer deliberation and deploys her complete-information optimal pricing strategy. Type-H firm can in equilibrium separate from type-L firm by positing a high price p H to motivate the consumer to deliberate. Intuitively, this deliberation-on- p H equilibrium can be sustained because it can be relatively more profitable for the high-type firm to induce consumer deliberation than for the low-type firm. Note first that, both firm types would earn the same profit, should they charge the same deliberation-preventing price (and perceived to be the same type). However, if both types charge the same price that induces consumer deliberation, the high-quality firm’s expected profit would be higher than that of the low-quality firm. This is because, the consumer would buy if and only if after deliberation the realized valuation is high, while the probability that the valuation is high is larger for the high-quality firm than for the low-quality firm (i.e., q H >q L ). As a result, the single-crossing condition with respect to the firm types’ incentive to induce deliberation can arise endogenously, resulting in the possibility to sustain the separating equilibrium.

To sustain the separating equilibrium, the deliberation cost must be high enough so that type-L firm prefers preventing deliberation to inducing deliberation. Thus, the condition c ≥ κ L is required. At the same time, the deliberation cost must also be low enough so that type-H firm prefers deliberation instead of following type-L firm’s strategy to thwart deliberation. This means that the condition c≤κ U must hold. Furthermore, to guarantee the existence of the separating equilibrium, type-H firm must have higher preference for deliberation than type-L firm does. Note first that, the consumer’s incentive to buy without deliberation from type-H firm increases with q H . This means that, for type-H firm not to adopt the deliberation-preventing strategy, q H cannot be too high. In addition, type-L firm’s incentive to depart from her deliberation-preventing strategy grows with the consumer’s valuation uncertainty (i.e., q L (1−q L )). As a result, the condition q H <1−q L (1−q L ) is necessary such that it is feasible for type-H firm to prefer consumer deliberation and for type-L firm not to do so. This necessary condition is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Next we elaborate on the equilibrium outcome. There are three possible scenarios. The first scenario occurs when q L (1−q L )≤c≤κ U and the consumer never deliberates if the product is perceived to be the low type. In this case type-L firm charges p L = q L and is able to capture all consumer surplus. The equilibrium price for type-H firm, p H =1−c/q H , is the highest price she can charge to promote consumer deliberation under complete information. The condition c≤κ U and the out-of-equilibrium belief guarantee that in equilibrium type-H firm prefers p H =1−c/q H to any other price. Moreover, this equilibrium is unique, because it is strictly dominated for type-L to deviate to any deliberation-inducing price and the high-quality firm can always make more profit by deviating from any deliberation-inducing price that is below p H .

The second scenario for the separating equilibrium is when \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } \le c < q_{L} (1 - q_{L})\) (and c≤κ U ), where \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } \equiv [1 / q_{L} (1 - q_{L}) + 1 / q_{H}]^{-1}\).Footnote 8 In this case deliberation may be desirable for the consumer if the product is perceived to be the low type. This means that type-L firm needs to lower her price to p L = c/(1−q L ) to prevent consumer deliberation. Type-H firm can continue to post the highest possible deliberation-inducing price, p H =1−c/q H , while escaping from type-L firm’s imitation. In particular, the condition \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c \ge \hat {\kappa }\) ensures that p L ≥ p H q L , and thus imitating the high-type’s equilibrium price is unprofitable for the low type. This equilibrium is also unique, because any price higher than p H =1−c/q H would lead to no demand and any lower price would result in either the low-type’s imitation or profitable deviation for the high type.

The third equilibrium scenario emerges when \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \hat {\kappa }\) (and c≤κ U ). Type-L firm still finds it optimal to charge the deliberation-preventing price p L = c/(1−q L ), but the type-H firm’s highest possible deliberation-inducing price 1−c/q H is not admissible any more. Should type-H firm continue to charge this price, type-L firm would deviate to mimic this strategy (in spite of consumer deliberation). As a result, type-H firm has to cut her price to p H = c/q L (1−q L ) to prevent imitation. Again this equilibrium is unique: a higher price than p H can lead to type-L firm’s imitation and a lower price is undesirable for the high-quality firm.

The following proposition formally characterizes how type-H firm’s equilibrium price in the separating equilibrium may depart from that under complete information.

Proposition 2

To facilitate discussion we focus on the parameter values for \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } < \kappa _{H}\), which ensures that all three scenarios stated in Proposition 2 are feasible. The condition for the first scenario is now reduced to κ H ≤c≤κ U . Type-H firm under complete information would like to hinder deliberation by charging c/(1−q H ). However, in the separating equilibrium the consumer deliberates on the equilibrium price of type-H firm. This involves charging a price 1−c/q H that is distorted upward from the complete-information optimal price. Not only does type-H firm’s profit shrink compared to the complete-information case, the social welfare also declines because the consumer in the separating equilibrium needs to incur the deliberation cost whereas no deliberation occurs under complete information.

In the second scenario \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } \le c < \kappa _{H}\), cheap signaling arises and no price distortion is needed to achieve separation. That is, type-H firm can charge the optimal price under complete information while making sure that type-L firm has no incentive to mimic this price. For this cheap signaling to happen, the deliberation cost has to be small enough (i.e., c<κ H ) so that promoting deliberation is type-H firm’s optimal choice under complete information, and large enough (i.e. \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c \ge \hat {\kappa }\)) so that type-H firm’s highest deliberation-inducing price 1−c/q H is unappealing to type-L firm. Note that this intermediate range of deliberation cost is non-empty if and only if \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } < \kappa _{H}\). This condition is equivalent to q L (1−q L )<q H (1−q H ), which implies that valuation uncertainty is lower for the low type than for the high type.

The third scenario in Proposition 2 (i.e., \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \min \{\hat {\kappa }, \kappa _{H}\}\)) demonstrates the possibility of downward price distortion for credible quality signaling. In this range of the deliberation cost, type-H firm under complete information charges 1−c/q H and entices the consumer to deliberate. By contrast, in the asymmetric-information case this price is too tempting for type-L firm to be the equilibrium price of type-H firm. Type-H firm has to be cut the price to c/q L (1−q L ) to sustain the separating equilibrium. Although the equilibrium profit of type-H firm is lower than that under complete information, the social welfare is the same because the consumer incurs the deliberation cost for both the separating equilibrium and the complete-information case. In other words, the downward price distortion under asymmetric information simply transfers part of type-H firm’s profit to consumer surplus.

In Fig. 3 we compare the impacts of the deliberation cost on type-H firm’s price and profit in the separating equilibrium with those under complete information, for the case \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\hat {\kappa } < \kappa _{H}\). Overall the equilibrium profit in the complete-information case has a “V-shaped” relationship with the deliberation cost, whereas the profit in the separating equilibrium exhibits an “inverted-V-shaped” pattern. When the deliberation cost is κ H <c<κ U , type-H firm’s optimal price and profit under complete information rise with c, because her equilibrium incentive is to ensure the consumer’s purchase without deliberation and a higher deliberation cost makes deliberation prevention easier. By contrast, the equilibrium price and profit of type-H firm under asymmetric information drop with c, because her equilibrium strategy is to distort the price upward to induce deliberation but a larger c reduces the consumer’s willingness to deliberate. It is worth noting that, although the upward price distortion diminishes as c increases, the profit distortion can be magnified. That is, a higher deliberation cost can enlarge the profit difference between the deliberation-preventing and the deliberation-inducing strategies.

When the deliberation cost becomes smaller (i.e., \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \hat {\kappa }\)), under complete information the equilibrium price of type-H firm is driven by inducing consumer deliberation. The higher the deliberation cost, the more difficult to induce deliberation and thus the less surplus type-H firm can grab from the consumer. As a consequence, both the equilibrium price and profit fall with c. By contrast, under asymmetric information the equilibrium price and profit of type-H firm increase with the deliberation cost c. This is because then type-H firm’s equilibrium price is driven by the need to prevent the low type’s imitation. A higher deliberation cost c boosts type-L firm’s equilibrium profit, thus escalating type-H firm’s equilibrium price and profit through mitigating the downward price distortion.

4.4 Pooling equilibria

We now investigate the pooling equilibrium in which both firm types set the same price p ∗ and the consumer does not update his belief from the prior. Let \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0} \equiv \phi q_{H} + (1 - \phi ) q_{L}\) be the consumer’s perceived average quality. As shown in Appendix B, there exists a pooling equilibrium in which the consumer purchases without deliberation if and only if c ≥ γ N , and there exists a pooling equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates if and only if c≤γ D . The pooling equilibrium of either type is generally not unique. In addition, it is possible that γ N <γ D . This means that the pooling-deliberation and the pooling-non-deliberation equilibria can co-exist.

Since the worst belief for the firm is to be perceived as type L, each of the two firm types should be able to obtain at least type-L firm’s complete-information maximal profit. As a result, in any pooling equilibrium in which the consumer purchases without deliberation, both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium profit should be no less than min{q L ,c/(1−q L )}. Similarly, in any pooling equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates, the equilibrium price should be equal to or greater than 1−c/q L for both firm types, and the equilibrium profit should be at least q L −c and q H −c q H /q L , for type-L firm and type-H firm, respectively. On the other hand, since the perceived average quality is \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0}\), in any pooling equilibrium in which the consumer purchases without deliberation, the highest equilibrium price and profit should be at most \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{N}^{*} \equiv \min \{\bar {q}_{0}, c / (1 - \bar {q}_{0})\}\). Similarly, in any pooling equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates, the equilibrium price cannot exceed \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*} \equiv 1 - c / \bar {q}_{0}\), and the equilibrium profit of type-L firm and type-H firm should be bounded by \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*} q_{L}\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*} q_{H}\), respectively. In fact, the higher bound of the equilibrium prices is the easiest to sustain, because it is the most attractive among the equilibrium prices under the respective equilibrium type.

The highest equilibrium prices under the pooling equilibria, \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{N}^{*}\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*}\), are both increasing in ϕ, the prior probability that the firm is of the high type. One may then expect that the pooling equilibria are easier to sustain as ϕ increases. The following proposition shows that this intuition may not necessarily hold.

Proposition 3

(i) γ N is weakly decreasing in ϕ. (ii) γ D is always increasing in ϕ if q H ≤1−q L (1−q L ), and γ D is increasing in ϕ over (0,(1−q L ) 2 /(q H −q L )] but decreasing in ϕ over [(1−q L ) 2 /(q H −q L ),1) if otherwise.

This proposition confirms that, as ϕ increases, it is indeed more likely to sustain the pooling equilibria in which the consumer purchases without deliberation. However, a higher ϕ may make it harder to sustain the pooling equilibria in which the consumer deliberates. On the one hand, the highest equilibrium price \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*}\) is increasing in ϕ. As a result, a higher ϕ gives the firm a higher incentive to choose the price \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{D}^{*}\). On the other hand, a higher ϕ may provide less incentive for the consumer to deliberate. Recall that the incentive for deliberation is positively influenced by the valuation uncertainty, \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})\). Because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})\) decreases with \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0}\) for \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0} \ge 0.5\), and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}_{0}\) increases with ϕ, the consumer can be less likely to deliberate as ϕ increases. Therefore, as ϕ grows, although the firm’s highest equilibrium price and equilibrium profit keep increasing, the existence condition for the pooling equilibria with deliberation can become easier to violate, i.e., γ D can be decreasing in ϕ. Overall, Proposition 3 demonstrates that the equilibrium threshold γ D can be non-monotonic in ϕ.

5 Dissipative advertising

In this section we extend the basic model to include advertising spending as an additional quality-signaling instrument. Nelson (1970, 1974) suggests that advertising can influence consumer behavior not only through hard information but also through the mere message that the advertiser is spending money (i.e., dissipative advertising). Following Milgrom and Roberts (1986), we assume that the firm can set the product price p and the amount of advertising spending a, which are both observed by the consumer. Advertising spending per se is dissipative and does not influence the consumer’s utility directly, but simply constitutes a direct cost in the firm’s profit. In this extended setup, the consumer’s posterior belief, μ(⋅|p,a), is conditional on the firm’s decision tuple (p,a). As a result, the consumer’s perceived quality \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\) can be influenced by both price and advertising.

Conditional on the perceived quality \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\), the consumer’s deliberation and purchase decisions are made in the same manner as those presented in Section 4.1, because here advertising can influence the consumer’s decisions only through the perceived quality. It follows that, under complete information, the signaling role of advertising is immaterial, and thus the optimal advertising spending should be zero.

We next investigate the incomplete-information case. We restrict our attention to separating equilibria. Denote the equilibrium prices of type-H firm and type-L firm as p H and p L , and the equilibrium advertising spending as a H and a L , respectively. Note first that, type-L firm should always deploy her complete-information optimal strategy. This means that type-L firm never advertises in any separating equilibrium, i.e., a L =0. Recall from Section 4.3 that there may be four possible types of separating equilibria. Nevertheless, when price is the only signaling instrument, Lemma 1 shows that the only possible type of separating equilibrium is the one in which the consumer deliberates on p H but not on p L . We now examine whether this result continues to hold when both price and advertising can be potential signaling devices.

Lemma 2

There exist separating equilibria in which the consumer purchases without deliberation if and only if \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c \ge \bar {\kappa }_{U}\) , where \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {\kappa }_{U} \ge \kappa _{U}\).Footnote 9 In equilibrium type-L firm sets p L = min{q L ,c/(1−q L )} and a L =0, and type-H firm sets p H ∈(p L ,min{q H ,c/(1−q H )}] and a H =p H −p L .

This result shows that, contrary to Lemma 1, if both price and advertising are the signaling devices, there exist separating equilibria in which the consumer purchases without deliberation. However, the equilibrium separation here is “dull” in the sense that the high type does not benefit from the separation at all and the advertising spending is purely dissipative. Actually both firm types earn the same equilibrium profit. This is because, even though the consumer updates his posterior belief about quality in response to different firm types’ equilibrium strategies, his equilibrium decisions remain the same. This implies that the equilibrium profiles have to be equally attractive to both firm types. If instead the equilibrium profile of type-j firm were more profitable than that of the other type, the latter firm would be better off imitating type-j firm’s strategy. This also explains why the equilibrium decisions of type-H firm are not unique, i.e., there are infinitely many price and advertising combinations for type-H firm that can keep type-L firm from mimicking.

Lemma 3

There exists a unique separating equilibrium of the deliberation-on-both type if and only if c< min{κ L ,q H (1−q H )}. In equilibrium type-L firm sets p L =1−c/q L and a L =0, and type-H firm sets p H =1−c/q H and a H =(p H −p L )q L .

This lemma shows that, contrary to Lemma 1, the deliberation-on-both type of separating equilibrium can be sustained when both price and advertising can be used as signaling instruments. Intuitively, the existence condition for this type of equilibrium is that the deliberation cost is small enough. In contrast to the no-deliberation type of equilibria characterized in Lemma 2, here type-H firm benefits from separating from the low type and achieves a higher equilibrium profit than type-L firm does. This is because upon deliberation the consumer has a higher probability of purchase from the high type than from the low type. As a result, all else being equal, consumer deliberation is more beneficial for type-H than for type-L firm. Consequently, type-H firm can optimally separate from type-L firm by charging the highest possible deliberation-inducing price (i.e., p H =1−c/q H ) and setting the level of advertising spending such that type-L firm does not find imitation profitable (i.e., a H =(p H −p L )q L ). In addition, unlike the no-deliberation type of equilibria, the deliberation-on-both type of equilibrium is unique.

Another consequence of type-H firm benefiting more from deliberation than type-L firm is that, there does not exist a separating equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates only upon learning that the firm is of the low type. Intuitively, dissipative advertising remains immaterial unless the pricing instrument yields positive gain of separation for the high type to protect.

Proposition 4

There exists a unique separating equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates on the high type but not on the low type if and only if κ L ≤c≤κ U . In equilibrium type-L firm sets p L = min{q L ,c/(1−q L )} and a L =0, and type-H firm sets p H =1−c/q H and a H = max{p H q L −p L ,0}.

This proposition shows that the deliberation-on-high type of equilibrium continues to exist in the extended setup. Nevertheless, the equilibrium strategy may be different from that in the basic model. Recall that, as shown in Proposition 1, if the deliberation cost is \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c < \hat {\kappa }\), in the basic model type-H firm needs to distort her equilibrium price downward from 1−c/q H to c/q L (1−q L ) to avoid type-L firm’s imitation. However, when advertising is feasible, downward price distortion is no longer necessary and type-H firm can always charge the highest deliberation-inducing price under complete information (i.e., 1−c/q H ). That is, type-H firm can use pricing to maximize her equilibrium profit while employing advertising spending to achieve separation. This is because money burning through dissipative advertising can be more cost effective than downward price distortion as an imitation-preventing device. Again, the driving force is that type-H firm can always earn a higher profit at any deliberation-inducing price than type-L firm can.

It is worth nothing that, without the need to distort type-H firm’s signaling price downward, the condition q H <1−q L (1−q L ) is no longer necessary to ensure the existence of the deliberation-on-high type of equilibrium. This suggests that the requirement for quality signaling becomes less stringent.

We then conduct comparative statics analysis to examine the impact of the deliberation cost on the equilibrium outcome in the extended model. We focus on type-H firm in the parameter range when the equilibrium is unique and different from that in the basic model (i.e., \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c \le \hat {\kappa }\)).

Proposition 5

-

(i)

When \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \hat {\kappa }\) , both the equilibrium advertising spending a H =p H q L −p L =q L −[q L /q H +1/(1−q L )]c and the equilibrium price p H =1−c/q H are decreasing in c, and the equilibrium profit π H =q H −q L +[1/q H +1/(1−q L )]q L c is increasing in c.

-

(ii)

When c<κ L , the equilibrium advertising spending a H =(p H −p L )q L =(1−q L /q H )c is increasing in c, and both the equilibrium price p H =1−c/q H and the equilibrium profit π H =q H −(2−q L /q H )c are decreasing in c.

This proposition suggests that the impacts of the deliberation cost on the equilibrium advertising spending and on type-H firm’s equilibrium profit are non-monotonic. In particular, the equilibrium advertising level exhibits an “inverted-V-shaped” relationship with c, and the equilibrium profit π H is first decreasing and then increasing in c. When the deliberation cost is in the range \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \hat {\kappa }\), the equilibrium is of the deliberation-on-high type. So type-H firm’s equilibrium price p H =1−c/q H decreases with c. However, the high-quality firm now needs to spend positive advertising to differentiate from the low-quality firm. As the deliberation cost increases, type-L firm’s equilibrium profit (i.e., π L = c/(1−q L )) improves, whereas the profitability of mimicking the high-quality firm’s pricing strategy drops. As a result, a larger deliberation cost makes it easier for type-H firm to avoid imitation, and thus the equilibrium advertising a H declines with c. How the equilibrium profit of type-H firm varies with c depends on the relative impacts on price p H and advertising a H . Proposition 5 demonstrates that the equilibrium profit is increasing in c, because the saving of advertising spending is larger than the loss of margin.

When the deliberation cost is smaller (i.e., c<κ L ), the unique separating equilibrium becomes the deliberation-on-both type. The equilibrium prices, p H =1−c/q H and p L =1−c/q L , both decrease with the deliberation cost. Since p L decreases with c at a faster rate than p H does, a higher deliberation cost actually makes it increasingly attractive for the low-quality firm to imitate the high-quality firm’s strategy. As a result, when the deliberation cost becomes higher, type-H firm needs to spend more on advertising to separate from type-L. Consequently, type-H firm’s equilibrium profit is decreasing in the deliberation cost c.

Next, we examine how the presence of dissipative advertising may influence the equilibrium outcome. We focus on comparing the differences under the separating equilibrium between the extended and the basic models.

Proposition 6

When \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} \le c < \hat {\kappa }\) , type-H firm’s equilibrium price and profit in the extended model are higher than those in the basic model, and the equilibrium consumer surplus and social welfare in the extended model are lower than those in the basic model.

This proposition reveals how the equilibrium outcome (of the deliberation-on-high type) under the extended model may be different from that when only the pricing instrument is present. It shows that dissipative advertising can boost the equilibrium profit of type-H firm, compared to that in the basic model. This is because the high-quality firm can resort to advertising spending rather than downward price distortion to separate herself from the low-quality firm. That is, the presence of dissipative advertising allows type-H firm to charge the highest deliberation-inducing price under complete information. In addition, Proposition 6 shows that the improvement in type-H firm’s profit is at the expense of consumer surplus and social welfare. This is because, whereas price distortion for the purpose of quality signaling in the basic model involves only a payoff transfer from the firm to the consumer, dissipative advertising here is purely money burning and socially wasteful.

To summarize, the general message in this section is that dissipative advertising can facilitate the signaling of quality. First, the scope of signaling can be expanded such that, certain types of separating equilibria that are otherwise nonexisting in the basic model, can now be sustained. In particular, as can be seen from Lemmas 2 and 3, both the no-deliberation and the deliberation-on-both types of equilibria can be supported in the extended setup. Second, the existence conditions for the separating equilibria are expanded to include a wider range of parameter values than in the basic model. In contrast to that in Proposition 1, Lemma 3 implies that the condition c ≥ κ L is not necessary any more (for the existence of some separating equilibrium). In addition, the deliberation-on-high type of separating equilibrium can be sustained even without the condition q H <1−q L (1−q L ). Third, dissipative advertising can substitute downward price distortion in the signaling of quality, thus improving type-H firm’s equilibrium profit.

6 Conclusion

Previous studies have proposed a variety of mechanisms that enable credible quality signaling, such as cost differential, consumer heterogeneity, presence of informed consumers, repeat purchase, etc. This paper suggests an alternative mechanism that allows a monopoly firm to signal quality through price to consumers that are ex ante homogenously uninformed. The driving force we propose is endogenous consumer deliberation. We show that consumer deliberation can be influenced by the perceived product quality, and that a deliberation-inducing price is relatively more appealing to a high-quality firm than to a low-quality firm. As a result, endogenous deliberation can constitute a mechanism to yield the single-crossing property between firms of different qualities. We demonstrate that there exists a unique separating equilibrium so long as the high quality is not extremely high and the deliberation cost is neither too high nor too low. In such an equilibrium, the high-quality firm charges a high price that motivates the consumer to deliberate, whereas the low-quality firm sets a low price that prevents deliberation.

We identify two kinds of price distortion in the high-quality firm’s signaling strategy. First, when the deliberation cost is sufficiently high, in the separating equilibrium the high-quality firm has to charge a higher price to induce deliberation, whereas a lower no-deliberation price can be more favorable under complete information. Conversely, when the deliberation cost becomes relatively low, to overcome the low-quality firm’s imitation, the high-quality firm may have to charge a lower price than the deliberation-inducing price that is optimal under complete information. As a result, the high-quality firm cannot always achieve the maximal profit under complete information. Moreover, the high-quality firm’s profit in the separating equilibrium exhibits an “inverted-V-shaped” relationship with the deliberation cost, in contrast to the “V-shaped” relationship in the absence of asymmetric information.

We also find that money burning through advertising can facilitate the signaling of quality. When advertising can be used as an additional signaling instrument, the scope of separating equilibrium can be expanded such that inducing different deliberation behavior is no longer needed to achieve separation. That is, there may exist separating equilibria in which the consumer always deliberates, or always purchases without deliberation, despite the updating of the posterior belief about quality. In addition, the admissible range of parameter values to support the separating equilibrium is expanded. Furthermore, in the equilibrium in which the consumer deliberates on the high quality, money burning can weaken the low type’s imitation incentive at a lower cost than price reduction. As a consequence, downward price distortion vanishes as advertising spending is sufficient to forestall the low-quality firm’s mimicking, raising the equilibrium profit of the high-quality firm at the expense of consumer surplus and social welfare.

Our model can be extended in several directions. For instance, one can examine alternative setups with respect to the relationship between quality and valuation uncertainty. It may also be interesting to investigate how consumer deliberation may interact with other driving forces of quality signaling. Another fruitful extension for future research is to consider alternative signaling instruments such as branding and product warranty.

Notes

In few exceptions the term “search” is used where purchase is possible without search (e.g., Kuksov and Villas-Boas 2010; Branco et al. 2012; Ke et al. 2015). This is similar to deliberation considered in this paper. Nevertheless, we will still use deliberation to differentiate from the standard meaning of search in the literature.

See also Kuksov and Lin (2010) on firms’ optimal provision of information in competitive markets.

This setup is adopted for simplicity. The insights here continue to hold in alternative specifications in which quality directly influences consumer utility, e.g., u = v q or u = v + q, where v captures valuation uncertainty and q represents quality.

Our model can accommodate cases in which deliberation cannot resolve all valuation uncertainty before purchase (e.g., the utility of goods with experience attributes can be known only after consumption). In these cases we can re-define V H and V L as the expected product valuations integrating over all residual uncertainty that cannot be resolved by deliberation.

Note that deliberation, as defined in this paper, does not represent other cognitive processes (e.g., evaluation and calculation of expected payoffs, reasoning about the firm’s incentive for signaling).

If a strategy p is dominated for both types of firms under any belief, then neither firm type would like to deviate to p, and so there is no need to specify the out-of-equilibrium belief for such p.

Note that \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\kappa _{L} < \hat {\kappa } < q_{L} (1 - q_{L})\).

Since [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 < min{q L (1−q L ),[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 }, there exists c such that the conditions are satisfied iff [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 <q H (1−q H ) ⇔ q H <1−q L (1−q L ).

As long as q H <1−q L (1−q L ), we have κ L <[1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 <q H (1−q H ). Hence there exists c such that the conditions hold iff q H <1−q L (1−q L ).

If \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}c < \bar {q} (1 - \bar {q})\), the consumer deliberates or opts out; otherwise, since \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p > c / (1 - \bar {q}) \ge \bar {q}\), he opts out.

The reason why p H >p is the following. Since c ≥ κ L is equivalent to p H ≥ 1−c/q L , we have either p H =1−c/q L >p (recall that p is an out-of-equilibrium price and so p≠p H ) or p H >1−c/q L ≥ p.

The consumer either deliberates or opts out after observing \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime }\) because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime } > p_{H}^{\prime } > c / (1 - q_{H}) \ge c / (1 - \bar {q})\).

It is not possible that \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime } = p_{H}\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}a_{H}^{\prime } < a_{H}\) because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}a_{H}^{\prime } \ge p_{H} q_{L} - p_{L}\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}a_{H}^{\prime } \ge 0\) imply \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}a_{H}^{\prime } \ge a_{H}\).

Under condition (b), it is impossible that p ∗ ≥ p q H for some price p∈(c/(1−q H ),1−c/q H ] while p ∗≤p ′ q L for some other price p ′∈(c/(1−q H ),1−c/q H ].

If \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}[1 / q_{H} (1 - \bar {q}_{0}) + 1 / q_{L}]^{-1} \ge \bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})\), then we have \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\frac {1}{\bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})} \ge \frac {1}{q_{H} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})} + \frac {1}{q_{L}} \Longrightarrow 1 \ge \frac {\bar {q}_{0}}{q_{H}} + \frac {\bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})}{q_{L}} \Longrightarrow q_{L} \left (1 - \frac {\bar {q}_{0}}{q_{H}}\right ) \ge \bar {q}_{0} (1 - \bar {q}_{0})\). Similarly to the proof of Lemma 16, this leads to a contradiction.

References

Bagwell, K., & Riordan, M. H. (1991). High and declining prices signal product quality. The American Economic Review, 81(1), 224–239.

Balachander, S. (2001). Warranty signalling and reputation. Management Science, 47(9), 1282–1289.

Bhardwaj, P., Yuxin C., & Godes, D. (2008). Buyer-initiated vs. seller-initiated information revelation. Management Science, 54(6), 1104–1114.

Branco, F., Sun, M., & Villas-Boas, J. M. (2012). Optimal search for product information. Management Science, 58(11), 2037–2056.

Branco, F., Sun, M., & Villas-Boas, J. M. (2016). Too much information? Information provision and search costs. Marketing Science, 35(4), 605–618.

Cho, I.-K., & Kreps, D. M. (1987). Signaling games and stable equilibria. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102(2), 179–221.

Desai, P. S., & Srinivasan, K. (1995). Demand signalling under unobservable effort in franchising: linear and nonlinear price contracts. Management Science, 41 (10), 1608–1623.

Feltovich, N., Harbaugh, R., & Ted, T. (2002). Too cool for school? Signalling and countersignalling. The RAND Journal of Economics, 33(4), 630–649.

Fudenberg, D., & Tirole, J. (1991). Game theory. Massachusetts: Cambridge.

Gerstner, E. (1985). Do higher prices signal higher quality?. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(2), 209–215.

Guo, L. (2015). Contextual deliberation and preference construction. Forthcoming, Management Science.

Guo, L. (2016). Contextual deliberation and procedure-dependent preference reversals. Working Paper, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Guo, L., & Hong, L. J. (2016). Rational anchoring in economic valuations. Working Paper, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Guo, L., & Zhang, J.J. (2012). Consumer deliberation and product line design. Marketing Science, 31(6), 995–1007.

Ke, T. T., Shen, Z.-J. M, & Villas-Boas, J. M. (2015). Search for information on multiple products. Forthcoming, Management Science.

Kihlstrom, R. E., & Riordan, M. H. (1984). Advertising as a signal. Journal of Political Economy, 92(3), 427–450.

Kuksov, D., & Lin, Y. (2010). Information provision in a vertically differentiated competitive marketplace. Marketing Science, 29(1), 122–138.

Kuksov, D., & Lin, Y.F. (2015). Signaling low margin through assortment. Forthcoming, Management Science.

Kuksov, D., & Villas-Boas, J. M. (2010). When more alternatives lead to less choice. Marketing Science, 29(3), 507–524.

Mayzlin, D., & Shin, J. (2011). Uninformative advertising as an invitation to search. Marketing Science, 30(4), 666–685.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1986). Price and advertising signals of product quality. Journal of Political Economy, 94(4), 796–821.

Moorthy, S., & Srinivasan, K. (1995). Signaling quality with a money-back guarantee: the role of transaction costs. Marketing Science, 14(4), 442–466.

Nelson, P. (1970). Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 78(2), 311–329.

Nelson, P. (1974). Advertising as information. Journal of Political Economy, 82(4), 729–754.

Schmalensee, R. (1982). Product differentiation advantages of pioneering brands. The American Economic Review, 72(3), 349–365.

Shugan, S. M. (1980). The cost of thinking. Journal of Consumer Research, 7 (2), 99–111.

Simester, D. (1995). Signalling price image using advertised prices. Marketing Science, 14(2), 166–188.

Soberman, D. A. (2003). Simultaneous signaling and screening with warranties. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(2), 176–192.

Srinivasan, K. (1991). Multiple market entry, cost signalling and entry deterrence. Management Science, 37(12), 1539–1555.

Tellis, G. J., & Wernerfelt, B. (1987). Competitive price and quality under asymmetric information. Marketing Science, 6(3), 240–253.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. Massachusetts: Cambridge.

Wernerfelt, B. (1988). Umbrella branding as a signal of new product quality: An example of signalling by posting a bond. The RAND Journal of Economics, 19(3), 458–466.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dmitri Kuksov, Paulo Albuquerque, Sameer Hasija, V. Padmanabhan, Kaifu Zhang, and attendees of 2015 Marketing Science Conference for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Technical Details for Separating Equilibria

1.1 A.1 Proof of Lemma 1

(i) & (ii) If the consumer’s deliberation decision does not change, then the firm with the lower price can always make a profitable deviation by imitating the firm with the higher price. (iii) Suppose in equilibrium the consumer deliberates on p L but not on p H . Type-L firm should not prefer to deviate her price p L to p H ; so p H ≤p L q L , which implies p H <p L q H . Yet type-H firm is willing to deviate to p L because p L q H >p H , a contradiction.

1.2 A.2 Proof of Proposition 1

In any separating equilibrium, type-L firm should always behave in the same way as she does under complete information. According to Lemma 1, we must have c ≥ κ L . We characterize the deliberation-on- p H type of equilibrium by showing the following lemmas. It requires the deliberation cost c<q H (1−q H ), which is omitted for clarity.

Lemma 4

For c ≥ q L (1−q L ), there exists a separating equilibrium iff c≤q H −q L . The equilibrium prices are unique: p H =1−c/q H and p L =q L .

Lemma 5

For [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 ≤c<q L (1−q L ), there exists a separating equilibrium iff c≤[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1.Footnote 10 The equilibrium prices are unique: p H =1−c/q H and p L =c/(1−q L ).

Lemma 6

For c<[1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 , there exists a separating equilibrium iff q H <1−q L (1−q L ) and c ≥ κ L .Footnote 11 The equilibrium prices are unique: p H =c/q L (1−q L ) and p L =c/(1−q L ).

1.2.1 Proof of Lemma 4— c ≥ q L (1−q L )

The proof proceeds in two parts: (A) There exists an equilibrium where p H =1−c/q H and p L = q L iff c≤q H −q L . (B) The equilibrium prices are unique.

-

(A)

[“Only if” part]: Suppose c>q H −q L and the equilibrium exists. Type-H firm wants to deviate to p L because π H = q H −c<q L = p L , a contradiction. [“If” part]: Type-H firm would not deviate to p L because π H ≥ p L . Type-L firm would not deviate to p H because π L = p L >(1−c/q H )q L = p H q L . We now show that neither type of firm has any incentive to deviate to any out-of-equilibrium price. For p<p L , type-L firm has no incentive to deviate; neither does type-H firm have any incentive because she does not even want to deviate to p L , not to mention a lower price p<p L . For p>c/(1−q H ), given any perceived quality \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\), the consumer either deliberates or opts out because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p > c / (1 - q_{H}) \ge c / (1 - \bar {q})\).Footnote 12 When the consumer deliberates, type-L firm would not deviate because π L = p L >p q L ; type-H firm would not deviate either because π H = p H q H >p q H . For p∈(p L ,c/(1−q H )], neither type of firm has any incentive to deviate under an out-of-equilibrium belief μ(q L |p)=1 because the consumer always opts out. The separating equilibrium with such an out-of-equilibrium belief survives the intuitive criterion because type-L firm wants to deviate under μ(q H |p)=1.

-

(B)

We prove this part by contradiction. Suppose the equilibrium price of type-H firm is \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime } < 1 - c / q_{H}\). According to Lemmas 1, \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime }\) has to be greater than c/(1−q H ). The consumer either deliberates or opts out for \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime } = 1 - c / q_{H}\) because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime } > p_{H}^{\prime } > c / (1 - q_{H}) \ge c / (1 - \bar {q})\) (where \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\) is any perceived quality). Since \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\pi _{L} = p_{L} > p_{H}^{\prime \prime } q_{L}\), type-L firm has no incentive to deviate to \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime }\) under any belief. Yet under the only reasonable belief \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\mu (q_{H} | p_{H}^{\prime \prime }) = 1\) in light of the intuitive criterion, type-H firm can make a profitable deviation to \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime }\), a contradiction.

1.2.2 Proof of Lemma 5— [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1≤c<q L (1−q L )

This is very similar to that of Lemma 4. The main difference is that here type-L firm charges c/(1−q L ) to forestall deliberation. We can show there exists a separating equilibrium iff c≤[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1. The condition c≤[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1 ensures that type-H firm prefers 1−c/q H to other prices.

1.2.3 Proof of Lemma 6— c<[1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1

We show the following: (A) There exists an equilibrium where p H = c/q L (1−q L ) and p L = c/(1−q L ) iff q H <1−q L (1−q L ) and c ≥ κ L . (B) The equilibrium prices are unique.

-

(A)

[“Only if” part]: Type-L firm’s equilibrium strategy requires that c ≥ κ L . Suppose q H ≥ 1−q L (1−q L ) and the equilibrium exists. Then p H ≤c/(1−q H ), which is not consistent with the desired consumer decisions (deliberation on p H ), a contradiction. [“If” part]: Note that the consumer deliberates on p H because p H <1−c/q H (implied by the premise c<[1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1) and p H >c/(1−q H ) (implied by q H <1−q L (1−q L )). Type-H firm is not willing to deviate to p L = c/(1−q L ) because π H = p H q H = c q H /q L (1−q L )>c/(1−q L ) = p L . Type-L firm is indifferent between p L and p H . We now examine the out-of-equilibrium prices. Neither type of firm wants to deviate to any price p<c/(1−q L ), p∈(c/(1−q H ),p H ), or p>1−c/q H under any belief. For any p∈(c/(1−q L ), min{c/(1−q H ),1−c/q L }], type-H firm is not willing to deviate under the belief μ(q L |p)=1 because p H >p and the consumer deliberates;Footnote 13 type-L firm does not want to deviate either because she does not even want to deviate to p H >p. For any p∈(1−c/q L ,c/(1−q H )]∪(p H ,1−c/q H ], no firm wants to deviate under μ(q L |p)=1 because p>1−c/q L implies that the consumer never purchases the product. The equilibrium with the out-of-equilibrium belief μ(q L |p)=1 (for any p∈(c/(1−q L ),c/(1−q H )]∪(p H ,1−c/q H ]) survives the intuitive criterion because type-L firm always prefers a deviation under a belief μ(q H |p)=1.

-

(B)

We prove by contradiction that any \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime } \in (c / (1 - q_{H}), c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L})) \cup (c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L}), 1 - c / q_{H}]\) cannot be the equilibrium price of type-H firm. Suppose it is. If \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime } \in (c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L}), 1 - c / q_{H}]\), then type-L firm wants to deviate to \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime }\) because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime } q_{L} > [c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L})] \cdot q_{L} = c / (1 - q_{L}) = p_{L}\), a contradiction. Otherwise, type-L firm is not willing to deviate to any price \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{H}^{\prime \prime } \in (p_{H}^{\prime }, c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L}))\) because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p_{L} = c / (1 - q_{L}) = [c / q_{L} (1 - q_{L})] \cdot q_{L} > p_{H}^{\prime \prime } q_{L}\).Footnote 14 Yet under the only reasonable belief \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\mu (q_{H} | p_{H}^{\prime \prime }) = 1\) according to the intuitive criterion, type-H firm would deviate, a contradiction.

1.2.4 Proof of Proposition 1

Define

It can be verified that

Combining Lemmas 4 and 5, for c ≥ [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1, there exists a separating equilibrium iff c≤ min{q H (1−q H ), max{q H −q L ,[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1}}≡κ U (except at the boundary q H (1−q H )). The above condition holds for some c iff [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1<q H (1−q H ) (because [1/q L (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1<[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1≤ max{q H −q L ,[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ]−1}); this is equivalent to q H <1−q L (1−q L ). Merging the results with Lemma 6, there exists a separating equilibrium iff q H <1−q L (1−q L ) and κ L ≤c≤κ U (except at the boundary q H (1−q H )). It can be verified that p H = min{1−c/q H , c/q L (1−q L )} and p L = min{q L , c/(1−q L )}.

1.3 A.3 Proof of Proposition 2

(i) Type-H firm charges c/(1−q H ) under complete information because κ H ≤c<q H (1−q H ), but she charges 1−c/q H in a separating equilibrium. Therefore, the price is higher in a separating equilibrium but the profit is higher under complete information (except for the boundary c = κ H ). The social welfare is lower in a separating equilibrium than under complete information because of the incurred deliberation cost in a separating equilibrium. (ii) In this region, type-H firm in a separating equilibrium follows her complete-information optimal strategy: p H = P H =1−c/q H . (iii) Type-H firm charges 1−c/q H under complete information but charges c/q L (1−q L )<1−c/q H in a separating equilibrium. So, the price and the profit are higher under complete information. Since the consumer deliberates for both cases, the social welfare is the same.

1.4 A.4 Proof of Lemma 2

Type-L firm adopts her complete-information optimal strategy. We discuss the existence conditions in four cases separately. The separating equilibria refer to the no-deliberation type.

Lemma 7

For c ≥ max{q L (1−q L ),q H (1−q H )}, there always exist separating equilibria. Type L: p L =q L and a L =0; type H: p H ∈(q L ,q H ] and a H =p H −p L .

Lemma 8

For q L (1−q L )≤c<q H (1−q H ), there exist separating equilibria iff c ≥ q H −q L . Type L: p L =q L and a L =0; type H: p H ∈(q L ,c/(1−q H )] and a H =p H −p L .

Lemma 9

For q H (1−q H )≤c<q L (1−q L ), there exist separating equilibria iff c ≥ [1/q H (1−q L )+1/q L ] −1 . Type L: p L =c/(1−q L ) and a L =0; type H: p H ∈(c/(1−q L ),q H ] and a H =p H −p L .

Lemma 10

For c< min{q L (1−q L ),q H (1−q H )}, there exist separating equilibria iff c ≥ [1/q H (1−q L )+1/q H ] −1 . Type L: p L =c/(1−q L ) and a L =0; type H: p H ∈(c/(1−q L ),c/(1−q H )] and a H =p H −p L .

1.4.1 Proof of Lemma 7— c ≥ max{q L (1−q L ),q H (1−q H )}

In this case, p L = q L and a L =0. The equilibrium price p H should satisfy p L <p H ≤q H . We prove that any p H ∈(q L ,q H ] and a H = p H −p L can be equilibrium decisions of type-H firm. Since both types of firms are indifferent between (p H ,a H ) and (p L ,a L ), it is sufficient to examine the out-of-equilibrium decisions. For any (p,a) such that p−a≤q L , no firm prefers a deviation under any belief. For any (p,a) such that p−a>q L and p>q H , the consumer opts out. For any (p,a) such that p−a>q L and p≤q H , neither type of firm wants to deviate under a belief μ(q L |p,a)=1, and such an equilibrium survives the intuitive criterion. It can be verified that any a ′≠p H −p L cannot be the equilibrium advertising spending of type-H firm.

1.4.2 Proof of Lemma 8— q L (1−q L )≤c<q H (1−q H )

In this case, p L = q L and a L =0. The equilibrium price p H should satisfy p L <p H ≤c/(1−q H ). We prove that any p H ∈(q L ,c/(1−q H )] and a H = p H −p L can be equilibrium decisions of type-H firm iff c ≥ q H −q L . [“Only if” part]: For c<q H −q L , we prove by contradiction that the above separating equilibrium does not exist. For p=1−c/q H , type-L firm does not want to deviate to p because p q L <q L . However, since q H −c>q L , type-H firm prefers to deviate to (p,0) under the only reasonable belief μ(q H |p,0)=1 according to the intuitive criterion, a contradiction. [“If” part]: It is sufficient to check the out-of-equilibrium decisions. For any (p,a) such that p−a≤q L , no firm prefers to deviate. For any (p,a) such that p−a>q L and p>c/(1−q H ), the consumer deliberates or opts out under any belief. The highest possible profit any firm can make is (1−c/q H )q H = q H −c≤q L ; so, no deviation takes place. For any (p,a) such that p−a>q L and p≤c/(1−q H ), neither type of firm wants to deviate under a belief μ(q L |p,a)=1, and such an equilibrium survives the intuitive criterion. It can be verified that a ′≠p H −p L cannot be type-H firm’s equilibrium advertising spending.

1.4.3 Proof of Lemma 9— q H (1−q H )≤c<q L (1−q L )

In this case, p L = c/(1−q L ) and a L =0. The equilibrium price p H must satisfy c/(1−q L )<p H ≤q H . We prove that any p H ∈(c/(1−q L ),q H ] and a H = p H −p L can be equilibrium decisions of type-H firm iff c ≥ [1/q H (1−q L )+1/q L ]−1. [“Only if” part]: For c<[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q L ]−1, we prove by contradiction that the above separating equilibrium does not exist. The consumer deliberates or purchases without deliberation on p=1−c/q L . Yet type-H firm wants to deviate to (p,0) because p q H >c/(1−q L ) ( ⇔ c<[1/q H (1−q L )+1/q L ]−1), a contradiction. [“If” part]: We just need to examine the out-of-equilibrium decisions. For any (p,a) such that p−a≤c/(1−q L ), no firm prefers a deviation. For any (p,a) such that p−a>c/(1−q L ) and p>q H , the consumer opts out because \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p > q_{H} \ge \bar {q}\) and \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}p > q_{H} \ge 1 - c / q_{H} \ge 1 - c / \bar {q}\) (where \(\phantom {\dot {i}\!}\bar {q}\) is any perceived quality). For any (p,a) such that p−a>c/(1−q L ) and p≤q H , the consumer deliberates if p≤1−c/q L but opts out otherwise under a belief μ(q L |p,a)=1. Neither type of firm wants to deviate because the highest profit any firm can earn is (1−c/q L )q H ≤c/(1−q L ) ( ⇔ c ≥ [1/q H (1−q L )+1/q L ]−1), and such an equilibrium survives the intuitive criterion. It can be verified that a ′≠p H −p L cannot be type-H firm’s equilibrium advertising spending.

1.4.4 Proof of Lemma 10— c< min{q L (1−q L ),q H (1−q H )}