Abstract

Asian countries have high demand for US dollars and are sensitive to US dollar funding costs. An important, but often overlooked, component of these costs is the basis spread in the cross-currency swap market that emerges when there are deviations from covered interest parity (CIP). CIP deviations mean that investors need to pay a premium to borrow US dollars or other currencies on a hedged basis via the cross-currency swap markets. These deviations can be explained by regulatory changes since the GFC, which have limited arbitrage opportunities and country-specific factors that contribute to a mismatch in the demand and supply of US dollars. We find that an increase in the basis spread tightens financial conditions in net debtor countries, while eases financial conditions in net creditor countries. The main reason is that net debtor countries are, in general, unable to substitute smoothly to other domestic funding channels. Policies that promote reliable alternative funding sources, such as long-term corporate bond market, or stable long-term investors, including a “hedging counterpart of last resort,” can help stabilize financial intermediation when US dollar funding markets come under stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

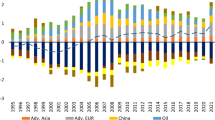

Korea is not shown in the chart due to the large size of CIP deviations. Deviations for the 1-year cross currency basis reached up to 597 basis points in 2008.

We present these possible factors with the caveat that there does not seem to be a factor (or factors) that can be applied uniformly across countries and over time. In this regard, this paper is consistent with Cerutti et al. (2019) who show that these factors do not uniformly apply across currency pairs and over time.

Coffey et al. (2009) show that an increased supply of US dollars by the Federal Reserve to foreign central banks via reciprocal currency arrangements (swap lines) did not have significant effect on narrowing the basis in the post-Lehman period. They explain that a heightened counterparty risk dominated, leading to a breakdown of arbitrage transactions.

FX derivatives are off-balance-sheet assets and it is difficult to have a direct measure of FX hedging demand.

According to this data, Australia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan POC and Thailand account for about 80% of open forex positions of all BIS banks in Asia region.

The argument is mainly related to the supply of dollar credit by lenders. As Avdjiev et al. (2017) argue, when there is potential for valuation mismatches on borrowers’ balance sheets arising from exchange rate changes, a weaker dollar improves the balance sheet of dollar borrowers, whose value of liabilities fall relative to their assets. Thus, for creditors, the stronger position of borrowers reduces tail risks in the credit portfolio and creates spare capacity for additional credit extension. So a depreciation of the dollar is associated with greater borrowing in dollars by non-residents and reduced CIP deviations and vice versa.

For example, see Kohlscheen and Andrade (2013) on the effects of currency swaps auctions carried out by the Brazilian Central Bank between the second half of 2011 to 2012 on the BRL/USD swap exchange rate.

The annual report by the Reserve Bank Australia (2016) notes “Reflecting this, the bulk of the foreign currency the Bank obtains from swaps against Australian dollars is Japanese yen. For the same reason, the Bank also swaps other currencies in its reserves portfolio against the yen to enhance returns. As a consequence, while the Bank’s exposure to changes in the value of the yen remains small (consistent with the yen’s 5% allocation in the Bank’s benchmark), around 58% of the Bank’s foreign exchange reserves were invested in yen-denominated assets at the end of June 2016.” More details could be found here: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/annual-reports/rba/2016/operations-in-financial-markets.html. Also, the speech by the deputy governor of RBA at the BIS Symposium in 2017 shows the investment in JGBs benefiting from negative basis of the JPY/USD FX swaps (https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2017/sp-dg-2017-05-22.html#fn3).

References

Akram QF, Rime D, Sarno L (2008) Arbitrage in the foreign exchange market: turning on the microscope. J Int Econ 76:237–253

Akram QF, Rime D, Sarno L (2009) Does the law of one price hold in International Financial Markets? Evidence from Tick Data. J Bank Financ 33(10):1741–1754

Arai, Makabe, Okawara, Nagano (2016) Recent trends in cross-currency basis. Bank of Japan Review 2016-E-7

Avdjiev, Du, Koch, Shing (2017) The dollar, bank leverage and the deviation from covered interest parity. BIS Working Papers No 592

Baba, Packer (2009a) From turmoil to crisis: dislocations in the FX swap market before and after the failure of Lehman Brothers. J Int Money Finance 28:1350–1374

Baba, Packer (2009b) Interpreting deviations from covered interest parity during the financial market turmoil of 2007–08. J Bank Financ 33:1953–1962

Baba, McCauley, Ramaswamy (2009) US Dollar money market funds and non-US banks. BIS Quarterly Review, March 2009

Baba N, Shim I (2011) Dislocations in the won-dollar swap markets during the crisis of 2007–09. BIS Working Papers, No. 344

Borio, McCauley, McGuire, Sushko (2016) Covered interest parity lost: understanding the cross-currency basis. BIS Quarterly Review, September 2016

Bottazzi, Luque, Pascoa, Sundaresan (2012) Dollar shortage, central Bank actions, and the cross-currency basis. Available at SSRN

Boz E, Gopinath G, Plagborg-Moller M (2017) Global trade and the Dollar, NBER working paper no. 23988

Bruno V, Kim S, Shin H (2018) Exchange rates and the working capital channel of trade fluctuations. BIS Working Papers, No. 694

Canzoneri M, Cumby R, Diba B (2013) Addressing international empirical puzzles: the liquidity of bonds. Open Econ Rev 24:197–215

Cerutti, Obstfeld, Zhou (2019) covered interest parity deviations: macrofinancial determinants. IMF working paper no. 19/14

Chakraborty S, Tang Y, Wu L (2015) Imports, Exports, Dollar Exposures, and Stock Returns. Open Econ Rev 26:1059–1079

Chinn M, Zhang Y (2018) Uncovered interest parity and monetary policy near and far from the Zero Lower Bound. Open Econ Rev 29:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9474-8

Coffey, Hrung, Sarkar (2009) Capital Constraints, Counterparty Risk, and Deviations from Covered Interest Rate Parity. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 393

Debelle (2017) How I learned to stop worrying and love the basis. Dinner Address at the BIS Symposium: CIP–RIP?

Du, Tepper, Verdelhan (2018) Deviations from covered interest rate parity. J Finance LXXIII(3)915–957

Goldman Sachs (2018) A new barrier to capital flows: USD-funding premium. Asia Economic Analyst, Seoul

Hwang K (2010) Efficiency of the Korean FX forward market and deviations from covered interest parity. Bank of Korea Institute for monetary and economic research working paper, no 419

Iida, Kimuar, Sudo (2016) Regulatory Reforms and the Dollar Funding of Global Banks: Evidence from the Impact of Monetary Policy Divergence. Bank of Japan Working Paper Series No. 16-E-14

IMF (2017) Asia: at risk of growing old before becoming rich? Regional economic outlook, Asia and Pacific, April 2017. Washington, DC

Ivashina, Scharfstein, Stein (2015) Dollar funding and the lending behavior of global banks. Q J Econ 2015:1241–1281

Kim B (2009) Market structure, bargaining and covered interest parity, Bank of Korea Institute for Monetary and Economic Research Working Paper, no. 365

Kohlscheen Emanuel, Sandro Andrade (2013) Official interventions through derivatives: affecting the demand for foreign exchange. Banco central do Brasil. Working papers 317

Mancini Griffoli, Thomas, Angelo Ranaldo (2010) Limits to arbitrage during the crisis: funding liquidity constraints and covered interest parity. Swiss National Bank Working Papers 2010–14

McGuire P, von Peter G (2012) The Dollar shortage in global banking and the international policy response. International Finance 15(2):155–178

Ramey V, Zubairy S (2018) Government spending multiplier in good times and in bad: Evidence from US historical data. J Polit Econ 126(2):850–901

Sushko, Borio, McCauley, McGuire (2016) The failure of covered interest parity: FX hedging demand and costly balance sheets. BIS Working Papers No 590

Wong A, Zhang J (2017) Breakdown of covered interest parity: mystery or myth? BIS papers no. 46

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank Eugenio Cerutti, Will Kerry, Peichu Xie, Yizhi Xu, Aki Yokohama, participants in the IMF APD seminar and RES/MCM surveillance meeting, and two anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions. We would like to also thank Ananya Shukla for excellent research assistance, Dulani Seneviratne for data support and Weicheng Lian for sharing Stata code. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Appendix

Appendix

Annex. A Simple Model of FX Hedging Demand

In this annex, we present a simple model of a non-U.S. bank’s demand for FX swaps to understand the implications of a higher basis and FX hedging costs on domestic financial conditions. The model is based on Ivashina et al. (2015) and Iida et al. (2016), which describes global bank’s demand for FX swaps.

We consider the following two scenarios that could affect bank’s demand for FX swaps: (1) an exogenous widening of the cross-currency basis; and (2) an increase in the interest rate differential. We assume that an increase in local currency (LCU)-denominated assets would lead to an easing of domestic financial conditions, while the opposite would lead to a tightening of domestic financial conditions.

A non-U.S. bank invests in two types of assets: USD-denominated assets (loans and bonds, etc.) that are issued by borrowers in the United States (LUS), and local currency (LCU)-denominated assets (LD) that are issued by borrowers in the domestic market. The expected gross return of loans will be gL(∙) and gUS(∙), respectively, which are concave functions of the amount of loans.

The bank faces an overall capital constraint on lending, where the aggregate lending cannot exceed capital: LUS + LD ≤ K. The constraint is more likely to bind with a tighter regulatory capital regime or higher external equity financing cost, in which case the bank would prefer to hold on to its capital instead of lending. As in Ivashina et al. (2015), the bank has a default probability of p and the size of the default is denoted by α.

On the liability side, the bank has three possible sources of funding: LCU-denominated funding (such as deposits) (DL), USD-denominated funding (DUS), and FX swaps (S). Following Iida et al. (2016), the cost of domestic funding is determined by cL(DL), comprising of two parts: the interest payment that the bank pays on its deposits and the convex cost of expanding the retail deposits. The interest rate paid to its depositors is the domestic risk-free rate, r, assuming that deposits are fully guaranteed by the government. The latter part assumes that the more the bank expands its retail deposits, the higher the cost it incurs. The cost of US dollar funding is determined by cUS(DUS), defined in a similar way as cL(DL), except that the default probability of the bank is taken into consideration (Fig. 10).

If the bank’s loans in USD exceed the liabilities in USD, the bank raises USD-funding from the FX swap market, as the bank does not take FX risks. The mismatch between assets and liabilities (US dollar funding gap) determines the bank’s hedging demand, i.e. demand for FX swap. The funding cost for FX swaps is determined as (rUS − r − ∆), where ∆ is the cross-currency basis. When CIP holds, ∆ is zero. Finally, we assume that the minimum size of liquidity needs is exogenous given and denoted by V.

As a result, the bank’s profit is determined by the following functions:

Here, τL and τUS are costs associated with the loans denominated in local-currency and US dollar, respectively. ηL and ηUS are the costs associated with changing the size of a bank’s balance sheets.

The objective of the bank is to maximize its profits, π, which is the sum of the following: (1) return on LL, (2) return on LUS, (3) cost of DL, (4) cost of DUS and (5) cost of FX swaps. The bank’s maximization problem is as follows:

subject to

Taking the first-order condition of the bank’s optimization problem and assuming that costs related to both increasing loans and balance sheets are the same for different currencies, i.e. τL = τUS and ηL = ηUS, the optimal amount of USD-denominated assets held by a non-US banks are given as follows:

Similarly, the optimal amount of local-currency denominated assets held by a non-US banks are derived as follows:

We consider the following two scenarios that could affect the bank’s demand for FX swaps: (i) an exogenous widening of cross-currency basis; and (ii) an exogenous increase in interest rate differential. From eqs. (1) and (2), we find that

-

An increase in cross-currency basis (Δ) will lead banks to increase their assets in local currency, and a decrease in US dollar-denominated assets. This is consistent with the findings in Ivashina et al. (2015).

-

An increase in the U.S. policy rates (qUS or qUS − rUS). If the Federal Reserve increases policy rate, driving the interest rate differentials to widen, ceteris paribus, this will lead banks to invest more in US dollar-denominated assets and less in local-currency denominated assets.

Net liabilities position vis-à-vis the US dollar. So far, we have implicitly assumed that the cost of domestic financing is relatively low, to ensure that the dollar gap exists and the demand for FX swaps takes a positive value. Let’s now consider a bank with net liabilities position vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar. This is relevant for banks in countries with net negative IIP position, such as emerging economies, where the cost of raising funding domestically may be high or limited. In the model, suppose the cost of raising funding (ηL) is very high. Ceteris paribus, this implies an inevitably high reliance on US dollar funding (DUS), as the equilibrium level of domestic funding (DL) is low. For this case, an increase in cross-currency basis (Δ) reduces the funding from FX swaps (S), but domestic financing cannot be raised to compensate for this reduction in funding. With higher costs of the U.S. dollar funding, overseas borrowing cannot be expanded either. The reduction in total liabilities leads the bank to reduce its overall assets, which will tighten domestic financial conditions.

Finally, an interesting case to consider, which we do not explore in the empirical section, is the case when both factors increase at the same time. For instance, the U.S. rate and the cross-currency basis may rise at the same time, as implicitly suggested by Avdjiev et al. 2017. Suppose the U.S. monetary policy eventually resumes its normalization path. It often involves strengthening of the US dollar against other currencies. According to Avdjiev et al. 2017, a strong U.S. dollar is correlated with a negative cross-currency basis. In such case, the bank’s decision for more offshore investment is not straightforward – despite a higher U.S rate, higher FX hedging costs will lower hedge-adjusted returns in USD-denominated assets. The net effects of these two forces would depend on the parameter values.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, G.H., Oeking, A., Kang, K.H. et al. What Do Deviations from Covered Interest Parity and Higher FX Hedging Costs Mean for Asia?. Open Econ Rev 32, 361–394 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-020-09594-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-020-09594-3