Abstract

I present new data from European French involving embedded polar response particles (a.k.a. yes/no particles) in response to negative questions and develop a novel proposal which integrates the insights of previous analyses (e.g. Holmberg in Lingua 128:31–50, 2013; Roelofsen and Farkas in Language 91(2):359–414, 2015). The main puzzle has to do with the interpretation of non ‘no’ (bare or followed by a clause), which may assert its antecedent or the negation of its antecedent. It is shown that the meaning of non-responses varies as a function of the scope of negation with respect to various operators in its antecedent. Polar response particles in French are analyzed as the spell-out of a Polarity head which has moved from a lower position. The various interpretations of polar response particles are modelled as being constrained by the interaction between the necessity of the movement of the Polarity head and a constraint on scope preservation. The ramifications of this proposal for related phenomena (e.g. ‘low negation’ in English, N-word responses) are then discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper is about polar response particles (PRPs) in European French—that is, oui, non, and si—and how the choice of covert clauses in their complement determines their interpretation.Footnote 1 By probing the interaction of quantifiers with negation in these covert clauses, it proposes a new analysis of these particles that builds on the insights of previous work on yes/no particles. I propose that PRPs spell out a Polarity head, which can have two different origins: it can be the copy of the Polarity head of the covert clause in its complement, or it can be a covert Polarity head that has been inserted as a last resort if there is an identity mismatch between the covert clause and the initiative the PRP responds to.

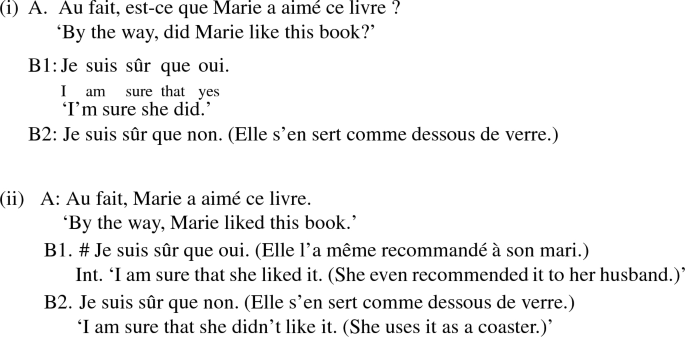

The main puzzle is illustrated by the contrast between (1) and (2): in response to the negative question in (1A), bare unstressed non in (1B) must signal agreement with the questioned proposition in A,Footnote 2 but in response to (2A) with unspecific quelqu’un ‘someone’, the same non-response cannot agree and must instead reverse the questioned proposition ‘Someone has not yet been received’.

The contrast can be summarized as in (3).

The intuition I would like to explore is that a sentence is negative when negation is the highest scope-bearing operator, and not negative otherwise—for instance, when negation is outscoped by a quantifier.Footnote 3 Following this intuition, the interpretation of non can be characterized by the following generalization (refined in Sect. 3): in response to a question, non conveys agreement when the question nucleus is negative as in (1); however, when the nucleus is not negative, non reverses its polarity.

In this paper I explore a way to derive this intuition about the polarity of propositions without ‘typing’ propositions as either positive or negative, thus dispensing with positing a new representational device in the grammar. The idea is that in both (1) and (2), non spells out an interpreted negation, but non is sensitive to whether the nucleus of the question it responds to is itself negative or positive. In cases like (1), this leads to there being still only one negation in the response; this is because interpreting negation in situ or with scope over the whole proposition (i.e. the latter corresponding to the position where non is pronounced) does not make a difference as far as truth conditions are concerned. In (2), however, interpreting clausal negation in situ, i.e. in the scope of unspecific quelqu’un ‘someone’, yields truth conditions that are different from the ones corresponding to a structure where clausal negation is interpreted where non appears, i.e. with scope over the whole proposition. In this case—and only in this case—a covert polarity head can be inserted and realized as non. This is why the response in (2) must contain two interpreted negations, yielding the reverse reading.

The paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, I give general background on French polar response particles, before describing the data on the interpretation of non in Sect. 3. In these sections, two sub-puzzles are flagged (‘sub-puzzles 1 and 2’), the solution to which will be shown to fall out from the analysis of the main puzzle. Section 4 presents the theoretical assumptions I make about French polar response particles and clauses, and in Sect. 5, I present the analysis of the main puzzle I described, as well as the two sub-puzzles flagged earlier. Section 6 explores the consequences of my analysis for related phenomena. Section 7 reviews a couple of outstanding issues for the account proposed in this paper, and Sect. 8 concludes.

2 Background on polar response particles in European French

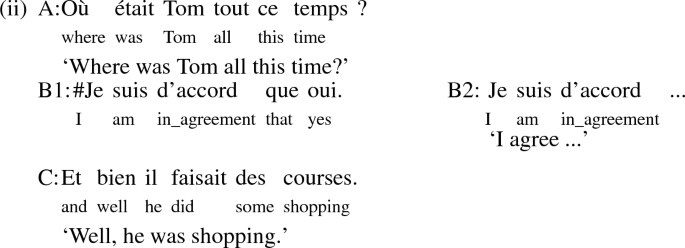

Consider the three polar response particles (PRPs) in French:Footnote 4oui, non, si. They are used to respond to two types of ‘discourse initiatives’ (Roelofsen and Farkas 2015): questions, as in (4A1), and assertions, as in (4A2).Footnote 5 French PRPs can appear embedded or not, bare (4B1/B4), accompanied by a fragment (4B2/B5), or at the periphery of a full clause (4B3/B6).

In this paper, I illustrate my arguments with embedded PRPsFootnote 6 (Authier 2013; Pasquereau 2018) responding to questions,Footnote 7 as matrix PRPs and responses to assertions pattern differently. Let me now give an overview of which PRPs can be used in the simple cases where the discourse initiative does not contain quantifiers.

In response to a positive question, oui and non have a univocal interpretation: the PRP oui conveys a positive answer, as in (5B1/B2), whereas non answers negatively, as in (5B3/B4).

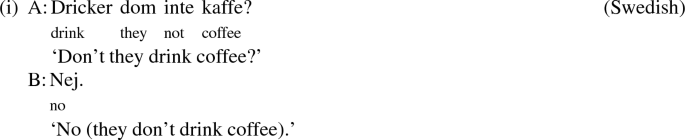

With questions containing a negation, things are a little bit more complicated since French presents features of both a polarity-based system and a truth-based system (Pope 1976).Footnote 8 In a polarity-based system, particles reflect the polarity of the response they convey regardless of the polarity of the utterance they respond to. This system is exemplified by the use of non: non conveys a response that has negative polarity regardless of the polarity of the question, which can be positive (5B3/B4 above) or negative (6B1/B2 below).

In a truth-based system, however, particles only encode whether the response they convey has the same or the opposite polarity as that of the utterance they respond to. This system is also exemplified by the use of non: non conveys disagreement in response to a positive question (5B3/B4)Footnote 10 or to a negative question (7B3/B4). European French thus uses both systems and this makes studying the meaning of French PRPs in response to negative questions less straightforward than studying responses to positive questions. Thus in response to the (low) negative counterpart of (5) in (6), oui and non both convey a (negative) agreeing answer.

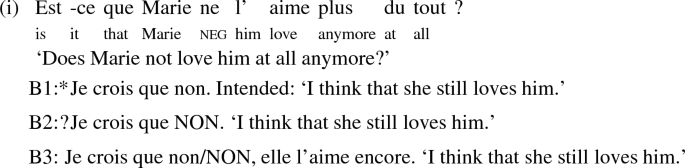

To express disagreement in response to the negative question in (6), repeated in (7), one can use the PRP si, in its bare form or clause-peripherally. Another possibility is to use clause-peripheral non followed by a clause which contradicts the question nucleus.Footnote 12 However, note that bare non (without any disambiguating phrase or clause) is not acceptable as a reversal particle. This contrast between clause-peripheral and bare non with respect to reversal of a negative question constitutes Sub-puzzle 1.Footnote 13

To summarize the patterns of responses we have seen so far, in (8) I use the feature system of Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) (itself inspired by the insights in Pope 1976). Each discourse initiative/response pair is characterized in terms of two features: absolute features [+, −] mark the response as having positive or negative polarity, whereas relative features [agree, reverse] signal how the response is related to the nucleus of the question it responds to.

The examples examined in this section are relatively simple inasmuch as they do not involve scope-bearing operators other than negation. The aim of this paper is precisely to look at what happens when the nucleus of the question a PRP responds to contains negation and another scope-bearing operator. I show that the answer to this question informs our understanding of the distribution of when non can realize an ‘agree’ response and when it must realize a ‘reverse’ response.

3 Empirical generalizations concerning the interpretation of non

In what follows, my focus is on the interpretation of the particle non: what controls its interpretation and what kind of prejacent it can take. I start in Sect. 3.1 with presenting the basic puzzle and establishing a descriptive generalization. In Sect. 3.2, I present data involving neg-raising predicates to show that the account of the interpretation of non must appeal to the syntactic representation of the question non responds to, while in Sect. 3.3 I consider data involving the aspectual scope-bearing adverbial toujours ‘still’ that show that the account must also appeal to the semantic representation of the question nucleus. Finally, Sect. 3.4 summarizes the pattern of data and gives the final descriptive generalization.

3.1 Ambiguity between ‘agree’ and ‘reverse’ readings

While in most cases bare non and clause-peripheral non behave the same way (syntactically and semantically), there are cases where clause-peripheral non does not behave like bare non (on the surface). For this reason, I describe them separately.

3.1.1 Bare ‘non’

In response to a positive question p?, answering with non asserts the negation of the question nucleus, i.e. \(\lnot \)p, whether p in the question contains a scope-bearing operator or not. Thus in (9), the non-response asserts the negation of the question nucleus ‘Olivier went to his place’, and in (10), the non-response asserts the negation of the question nucleus ‘Someone went to his place’ (where ‘someone’ is interpreted unspecifically).

The pattern can be summarized as in (11): when the question does not contain clausal negation, the non-response asserts the negation of the clausal nucleus—in other words, it reverses it.

Throughout the paper, I use questions as discourse initiatives and non embedded under Je crois que ‘I think that’. For this reason, I take the liberty not to represent either the question operator or the embedding predicate in the summaries below. I now look at questions that contain (low) clausal negation. I begin in (12) with the negative counterpart of the example we started with in (9). The fact that the question is now negative does not change the meaning of the non-response: it agrees with its negative question nucleus.

In the next examples, I look at the same question except that now the subject is an (unspecific) existential quantifier. A question initiative containing a quantifier and negation changes the interpretation of the reply depending on the relative scope of the quantifier and clausal negation. If the existential quantifier has scope over clausal negation, the non-response cannot agree with the question nucleus and must reverse it. In (13), the (unspecific) existential quantifier contributed by quelqu’un ‘someone’—being a positive polarity item—must be interpreted outside the scope of negation. The non-response can only reverse the question nucleus and mean that it is not the case that someone has not been to Jean’s place.

If the existential quantifier has scope below clausal negation, the non-response can agree with the question nucleus. In (14), the existential quantifier is contributed by the N-word personne ‘no one’, which must be interpreted in the scope of negation. There, the non-response agrees with the question nucleus and means that, indeed, no one has been to Jean’s place.

The pattern with negative questions can be summarized as in (15): when the question nucleus contains clausal negation, bare non reverses it unless negation is the highest scope-bearing operator.

I propose the generalization in (16) to describe the patterns summarized in (11) and (15).

So far we have only looked at existential quantification in subject position, but in what follows, I give further examples to illustrate this generalization and show that it also holds with universal quantifiers, whatever their syntactic position or syntactic category. In the next example I look at a negative question containing the \(\forall \) quantifier in the DP tout le monde ‘everyone’ in subject position. Although, tout ‘all’ preferably takes scope under negation in French, both scope relations are possible with enough contextual support. Thus in (17), the context is such that the speaker in A wants to check that the rumor that no one has died is true (this is facilitated by emphasizing tout le monde with intonation; see Sect. 7.2 for a discussion of the effect of focussed DPs). The non-response can only have the reversal meaning.

With the same question involving tout le monde ‘everyone’, the other, easier scope relation, \(\lnot \forall \), yields a different response pattern with non since it must agree.Footnote 14

The syntactic position of the phrase containing the scope-bearing element does not matter: it can be the subject, as in the examples so far, but it can also occur in object and oblique positions, as in (19).

In fact, the scope-bearing element can even be contributed by non-arguments like verbs and adverbs. For instance, depending on whether the adverb souvent ‘often’ is interpreted inside or outside the scope of negation, non can agree or not, as illustrated in (20) and (21) respectively.

Adding the exclusive adverb seul ‘only’ triggers the same effect: a non-response cannot agree.Footnote 15 In the question in (22), the adverb seule is associated with the focussed DP Marie. The non-response may only reverse the nucleus and assert that other people (other than Marie) did not finish their plate. In this and similar cases, the only way to give an agreeing response is with oui (22 B2).

I have tested several scope-bearing operators (in subject, object, and oblique positions (where applicable)).Footnote 16 I summarize the data in (23).Footnote 17

The generalization is the following: bare non conveys agreement when the highest-scope bearing operator in the question nucleus is negation; otherwise it conveys reversal.

Note that whatever the number of operators in the question nucleus, all that matters is the height of clausal negation relative to these operators.Footnote 18 Thus in (25), a response with non reverses the question nucleus containing the sequence \(\exists>\lnot >\exists \).

3.1.2 Clause-peripheral ‘non’

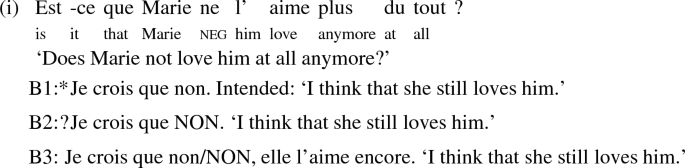

In (26) the agreement reading that is available with bare (unaccented) non in (26 B1) is still available with clause-peripheral non in (26 B2). In addition, clause-peripheral non makes available the other reading, i.e. the reversal reading in (26 B3), provided the prejacent (the clause to the right of a PRP) denotes a proposition that is the negation of the question nucleus in A.

When bare non has the reversal reading in (27 A) (because negation is not the highest scope-bearing operator in the question nucleus), clause-peripheral non also has this reading; cf. (27 B2). However, here clause-peripheral non does not make available the other reading, i.e. the agreement reading. In fact, as (27 B3) shows, if the prejacent does not reverse the question nucleus, the construction is just ill-formed in this context. This is Sub-puzzle 2.

Therefore, it is not the case that “anything goes with clause-peripheral non”: it can be used to convey agreement with a question nucleus only if the highest scope-bearing operator is negation. The table in (28) presents a summary of the data relevant to clause-peripheral non alongside the bare-non data we saw in the preceding section.

The generalization is as follows: when the highest scope-bearing operator in the question nucleus is negation, clause-peripheral non can convey agreement or reversal (with a prejacent that denotes the same proposition as the question nucleus or its negation, respectively). Otherwise, clause-peripheral non can only convey reversal.

3.1.3 Summary

With respect to the main puzzle we started out with in the Introduction—the effect of quantifiers outscoping negation on the interpretation of non—bare non and clause-peripheral non behave similarly: when the highest scope-bearing operator in the question nucleus is negation, non conveys agreement; otherwise non conveys reversal.

In addition to this main puzzle, we see that clause-peripheral non, unlike bare non, can always convey reversal (even when the highest scope-bearing operator in the question nucleus is negation) (Sub-puzzle 1) but only if the prejacent denotes a proposition that is the negation of the question nucleus (Sub-puzzle 2). I summarize in (29) the main puzzle as well as the two sub-puzzles which will be given an analysis in Sect. 5.

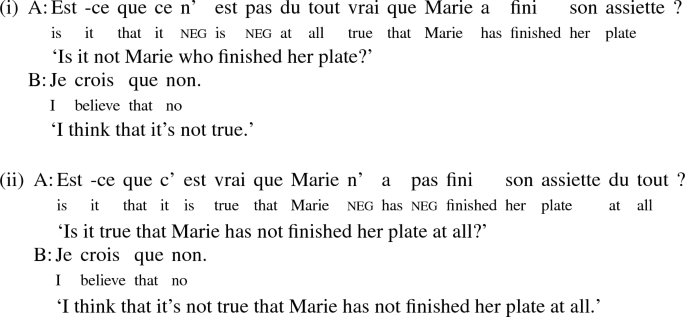

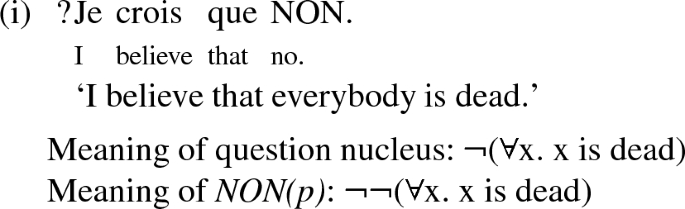

I have remained agnostic as to which level of representation—e.g. syntactic or semantic—the descriptive generalization for the main puzzle should be stated at:Footnote 19 in all the cases examined up to now, semantic and syntactic scope have been aligned. In order to address this question, I look at a case of misalignment between the semantic and the syntactic scope of negation: examples containing negated neg-raising predicates, where negation is outside the syntactic scope of the quantificational operator but interpreted within its semantic scope. Neg-raising predicates show that the generalization must have access to the syntactic representation of the scope relations.

3.2 Neg-raising: the generalization should be stated at LF

In Bartsch (1973) neg-raising is taken to be a purely semantic/pragmatic phenomenon; that is, contrary to what its name suggests, neg-raising does not in fact involve the raising of negation in the syntax. For instance, in the question in (30) containing the neg-raising predicate vouloir ‘want’, negation is assumed to be where it appears—in the matrix clause, with vouloir ‘want’ in its scope.

The neg-raiser vouloir ‘want’ achieves wide scope over (semantic) negation via an ‘excluded middle inference’, as laid out in (31).

Let’s entertain for the sake of argument that the generalization in (16) could be stated in terms of semantic scope relations. Since, according to the excluded-middle analysis of neg-raising (Bartsch 1973), neg-raising predicates constitute a case where semantic and syntactic scope come apart, a response to (30) containing embedded non, like (32), is predicted to have different interpretations depending on whether the generalization is stated at LF or at the semantic level.

If negation at LF matters, we expect an embedded non-response like (32) to the question in (30) to convey agreement and mean ‘She wants not to finish her plate at all’ (after the excluded-middle presupposition has been taken into account). If, however, semantic negation matters, we expect the embedded non-response to convey reversal and mean ‘It is not the case that she wants not to finish her plate at all’.

Responding with (32) to (30) conveys agreement, i.e. ‘I think that she wants not to finish her plate at all’. The meaning of the embedded non-response is predicted if the descriptive generalization in (16) is stated over its LF representation, but not if it is stated purely in semantic terms.Footnote 20

3.3 Non-quantificational scope-bearing operators: the generalization should be stated in the semantics

This section examines the pair toujours pas ‘still not’ / pas encore ‘not yet’ illustrated in (33).Footnote 21 The adverb toujours with the meaning ‘still’ must not be anti-licensed by clausal negation, whereas encore can occur in the scope of negation. This is perhaps most apparent in fragment answers to polar questions. The sequence pas toujours can only mean ‘not always’; toujours must appear before pas to mean ‘still’, otherwise the word encore ‘yet’ is used.

A non-answer to a negative question containing encore asserts the negative question nucleus—as expected, since negation is the highest scope-bearing operator in it.

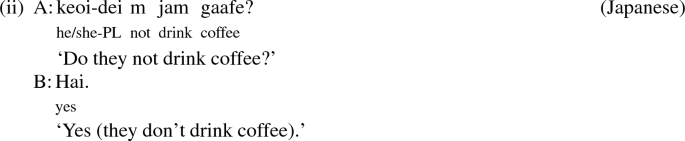

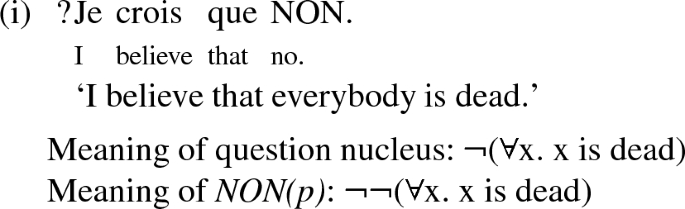

Given that toujours ‘still’ must take scope above negation, we might expect that, like other scope-bearing operators, it blocks the use of \(\textit{non}_{agree}\). However, as (35) shows, a non-response to such a question conveys agreement.

It might seem that the operator toujours ‘still’ is a counterexample to the generalization we have so far entertained. However, I hypothesize that the generalization can be kept, provided it is refined a little. The intuition is that the adverb toujours ‘still’ is not quantificational and does not create a truth-conditional ambiguity. The analysis must then differentiate between scope-bearing operators that create a truth-conditional ambiguity and those that do not.

3.4 Descriptive generalization

We saw in Sect. 3.1.3 that when the highest truth-conditional ambiguity-creating scope-bearing operator in the question nucleus at LF is negation, non—whether bare or clause-peripheral—conveys agreement; otherwise it conveys reversal (main puzzle). In addition, while bare non can sometimes but not always convey reversal (i.e., when the condition above is met), clause-peripheral non can always convey reversal (Sub-Puzzle 1), provided the prejacent denotes the negation of the question nucleus (Sub-Puzzle 2).

In the next subsection, data involving neg-raising predicates showed that the main puzzle generalization must appeal to the LF representation of the scope-bearing operators, and the toujours ‘still’ data showed that the interpretation of non is sensitive to whether operators outscoping negation at LF create a truth-conditional ambiguity or not.

In what follows, I argue that this generalization falls out from the interaction of two independent elements: (i) a general syntax/semantics for PRPs—which, among other things, predicts that non is the realization of two underlying morphemes, negation or a reverse feature, in line with previous work—and (ii) the assumption that covert negation can be inserted as a last resort rescue strategy under ellipsis, following Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016).

4 Theoretical background

The purpose of this section is to outline the assumptions I make about the structure of French clauses in general, and of clauses containing a PRP in particular. I assume that PRPs in French are the spell-out of a Pol(arity) head whose contents require certain conditions to hold between the PRP response and the discourse initiative it responds to. My analysis builds on the idea in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) that PRPs spell out Pol heads which host two types of features—relative and absolute—though I depart from their specific proposal in a few ways.

4.1 PRPs are the realization of Pol

Following Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) and Pasquereau (2018), I assume that PRPs in French are the spell-out of a Pol head (see Sects. 4.3 and 4.4 for refinements of this proposal). Only reactive assertions have a Pol head. I assume that the basic structure of a clause containing a PRP is as in (36): the Pol head takes a full clause—the prejacent—as its complement.

The prejacent can optionally be elided under semantic identity with some constituent in the preceding question (e.g. TP, VP). I call this constituent the ‘ellipsis antecedent’. Thus, what I have referred to until now as bare and clause-peripheral PRPs are in fact two realizations of the same underlying structure. I use Merchant’s (2001) notion of e-givenness for semantic identity, defined in (37).

Notice that the definition licenses PF deletion of the prejacent under semantic identity with some ellipsis antecedent, not necessarily always the same constituent. Just as different constituents can introduce different discourse referents, an elided constituent can be interpreted with respect to different parts of a preceding utterance.Footnote 22

4.2 PRPs are anaphoric expressions

PRPs, whether bare or followed by a sentence, are anaphoric expressions, i.e. they are interpreted relative to a constituent in the previous discourse. For instance, compare (39) and (40): bare or clause-peripheral non cannot agree if a question is positive (39a), but it can if the question is negative (40a); likewise, bare or clause-peripheral si can reverse if the question is negative (40b) but not if the question is positive (40a).

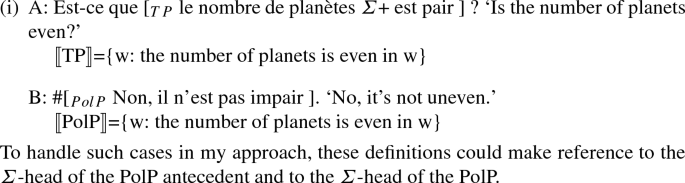

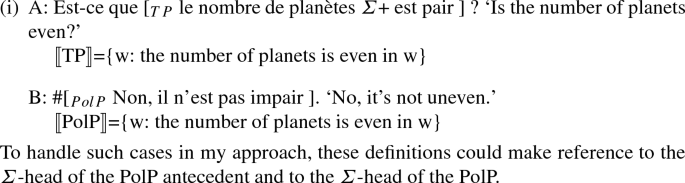

The constituent relevant for the interpretation of PRPs is not necessarily exactly the same as the ellipsis antecedent (see (58) in Sect. 5.1.1 below for an example). Therefore I call the constituent (in the question) that is relevant for calculating the interpretation of the PRP the ‘PolP antecedent’ (PolP being the constituent that the PRP heads in the response). In this paper, I assume that the PolP antecedent (i.e., the antecedent relevant for the interpretation of a PRP) is always the nucleus of the preceding question, i.e. the TP in (41). By contrast, the ellipsis antecedent is sometimes the whole TP, sometimes a smaller constituent (e.g. the VP in (58) below).Footnote 23

The Pol head is the seat of two types of information: it encodes the polarity of the prejacent and it encodes whether the prejacent agrees with the PolP antecedent or reverses it. In Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) (following proposals in Farkas and Bruce 2010; Farkas 2010; Pope 1976), these are encoded as two bivalent features base-generated in Pol; see (42) below. The absolute polarity feature marks the prejacent of Pol as being positive or negative, whereas the relative polarity feature marks the response as agreeing or reversing the antecedent.

I slightly depart from the specifics of the account in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) since I propose that what they formalize as ‘absolute features’ are in fact polarity heads, not features. In the next section, I explain how Pol comes to reflect the polarity of the prejacent.

4.3 The \(\varSigma \)-head and movement to Pol

Following Sailor (2012), Kramer and Rawlins (2011), Roelofsen and Farkas (2015), Gribanova (2017), I assume that every sentence has a head with a polarity feature which is valued positively or negatively. I call this head \(\varSigma \). Thus the question in (43a) has the LF in (43b), and the assertion in (44a) has the LF in (44b).Footnote 24

On the semantic side, I assume that an interpretable positively-valued \(\varSigma \)-head is an identity function, whereas an interpretable negatively-valued \(\varSigma \)-head takes a proposition and reverses its polarity, as schematized in (45).

In this paper I also assume that (i) Pol must agree with a \(\varSigma \)-head, which then must undergo head movement to PolFootnote 25 (under the copy theory of movement, Chomsky 1992) and that (ii) the higher copy of \(\varSigma \) is interpreted.Footnote 26 Note that only one copy of \(\varSigma \) can be interpreted, thus the movement does not seem to leave a trace (reconstruction is not possible). Moreover, while only the high copy of \(\varSigma \) is interpreted, both copies are pronounced: the copy in Pol is spelled out as a PRP (see realization rules in Sect. 4.5), whereas the lower copy is spelled out as ne if it is \(\varSigma -\) and as a silent morpheme if it is \(\varSigma \)+.

Both claims are independently made and argued for in Gribanova (2017) in order to account for the different realizations of polarity focus in Russian. I assume that Pol has the denotation in (47) and combines with \(\varSigma \) via function application.Footnote 27 The meaning of Pol is purely presuppositional, as I discuss further in Sect. 4.4.

Thus in this system, what Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) call ‘absolute features’ are not features but the copy of a lower Polarity head. I show in Sect. 5 that extending these claims to French, when combined with the account in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015), correctly predicts the pattern of interpretation of non-responses. I now turn to examining the presupposition part of the denotation of Pol.

4.4 Two types of Pol heads

Following Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) but in the vein of Gribanova (2017), I assume that there are two Pol heads in French: one marked with a feature [reverse], \(\hbox {Pol}_{reverse}\), and another marked with a feature [agree], \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\). These features encode a presupposition that the whole PolP must satisfy (48).

Remember that there are two notions of antecedent: the ‘PolP antecedent’ for the meaning of PolP and the ‘ellipsis antecedent’ for the prejacent of PolP in case of ellipsis. Thus, the example in (46) has the syntax in (49a) and the interpretation in (49b).

4.5 Realizational rules in French

Based on the description of the data in Sect. 2, I assume the rules in (50) for French PRPs.

As a consequence of (50), the connection between the four possible feature combinations and the three PRPs in French is as in (51).

4.6 Covert \(\varSigma \) insertion as a last resort

Ovalle and Guerzoni (2004), Zeijlstra (2008) and Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016) assume that a covert negation can be inserted in a high projection only when part of the structure has been elided (52).

This assumption correctly captures an asymmetry in the interpretation of an N-word in full sentences versus fragments in Romanian. The full sentence in (53) can have the negative concord reading, whereas the double negative reading is not possible.

Interestingly, if the same N-word is used as a fragment answer to a negative wh-question, as in (53), the double negation reading becomes available.

Assuming that N-word fragment answers are derived via ellipsis from an underlying structure like (53), Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016) analyze the double negation reading in (54) as arising from the insertion of negation high in the structure. Crucially, the double negation reading is not available in (53), because covert negation can only be inserted when vP is elided.

I follow Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016) in assuming that covert \(\varSigma -\) insertion is limited to elliptical constructions. In fact, I further extend this assumption to \(\varSigma \)+. We will see that covert \(\varSigma \) insertion only being available when the prejacent is elided explains Sub-puzzle 2. It is not the case that covert \(\varSigma \) insertion is freely available. If it were, we would expect unaccented bare non to be able to convey reversal in examples like (55). But it crucially does not: bare unaccented non can only convey agreement in (55).

I contend that insertion of covert \(\varSigma \) is a last resort “rescue mechanism” limited to elliptical constructions, as stated in (56).

5 Analysis

Let me list the core pieces of my analysis:

I present my analysis of the main puzzle in two steps: first, I cover bare non; then I consider clause-peripheral non, in the process explaining Sub-puzzles 1 and 2.

5.1 Bare non

5.1.1 Basic cases

In response to a question nucleus whose highest truth-conditional operator is negation, a non-response has the structure in (58b): the \(\varSigma \)-head moves to Pol, which is valued for the ‘agree’ feature. The presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) is met since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \) is equivalent to its (PolP) antecedent \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in the question. The Pol head is spelled out as non, as per the morpho-phonological rules in Sect. 4.5. The prejacent/TP in the response can be elided since the identity condition on ellipsis is met: the TP complement of Pol is e-given with respect to the VP constituent in the question, the ellipsis antecedent (remember that only the highest copy of \(\varSigma \) is interpreted).

The same non-response to a positive question like (59) is always reversing. The \(\varSigma \)-head in the prejacent moves to Pol and is interpreted there. The reversal presupposition is met since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \) is equivalent to the negation of \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in the question. Ellipsis is possible since TP in the response is e-given with respect to TP or VP in the ellipsis antecedent (only the highest copy of \(\varSigma \) is interpreted).

If in (59B) \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) had been merged instead of \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\), the agree presupposition would not have been met since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \)=\(\lnot \)Marie finished and the PolP antecedent \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) = Marie finished.

5.1.2 Quantificational operators outscoping negation

We have talked about the possibility of inserting covert \(\varSigma \) under ellipsis, and now we are going to see the effect of this assumption. In response to the question in (60A), I claim that bare non must have the underlying structure in (60b). To see this, consider the alternative underlying structure in (60a), in which the prejacent is identical to the PolP antecedent before the polarity head \(\varSigma -\) has moved to Pol (\(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) or \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\)): \(\varSigma -\) is interpreted in Pol but the effect of this is that neither the agreement nor the reversal presupposition are met. Moreover, no constituent in the ellipsis antecedent is e-given. The only way to meet the reversal Pol head presupposition is to leave \(\varSigma -\) in its base-generated position and, as a rescue strategy, to insert covert negation, which then agrees with and moves to Pol, as in (60 b). In this case, the \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\) presupposition is met since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \)=\(\llbracket \lnot \)TP\(\rrbracket \).Footnote 30 The Pol head is spelled out as non, as per the morpho-phonological rules in Sect. 4.5. The TP in the response can be elided since the identity condition on ellipsis is met: TP is e-given with respect to the TP constituent in the question.

Another example of a quantificational operator forcing reversal non is (62), where negation is interpreted in the scope of the focus-sensitive operator seul ‘only’. In (62), the adverb seul ‘only’ associates with the focussed argument Marie. I assume, following Rooth (1992)/Horn (1996), that seul ‘only’ contributes universal quantification and has the meaning in (61).

Here again, a non-response cannot agree: if \(\varSigma -\) moves to Pol, as in (62b), the denotation of PolP is such that neither the presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) nor that of \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\) is met (62b). The only way to obtain a felicitous LF that will both satisfy agree with Pol and the presupposition of at least one Pol head is to resort to covert \(\varSigma \) insertion, as in (62c), with \(\varSigma \) then moving to Pol.

The presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\) is met since \(\llbracket \hbox {PolP}\rrbracket \) is equivalent to the negation of \(\llbracket \hbox {TP}\rrbracket \) in the question. The Pol head is spelled out as non, according to the morpho-phonological rules in Sect. 4.5. The TP in the response can be elided since the identity condition on ellipsis is met: TP is e-given with respect to the TP constituent in the question.

The fact that non cannot convey agreement is explained in the current analysis because interpreting sentential negation in Pol would change the scope relation between the universal quantifier contributed by seul ‘only’, on the one hand, and negation, on the other. This in turn would fail to satisfy either the agreement or the reversal presupposition of the Pol head.

5.1.3 Neg-raising

Since I assume the pragmatic analysis of neg-raising in Bartsch (1973), the logical form of (63B) has negation in the matrix clause. Via agree, \(\varSigma -\) moves to Pol and is interpreted there. The presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) is met since \(\llbracket \hbox {PolP}\rrbracket \) is equivalent to the TP in the question after the excluded middle presupposition has been factored in. The TP in the response can be elided since the identity condition on ellipsis is met: TP is e-given with respect to the VP constituent in the question.

5.1.4 Non-quantificational operators outscoping negation

Recall that the aspectual adverb toujours ‘still’ does not force the reversal reading of non. I assume that toujours is the spell-out in French of an operator still. I assume the semantics in (64/65), following Ladusaw (1978, (1979), and Löbner (1989), as cited in Krifka (2000).

This is so because an operator like aspectual toujours ‘still’ does not create a truth-conditional ambiguity: whether it is interpreted below or above negation, the truth conditions of the sentence that contains it do not change. Thus, when negation is interpreted high, as a result of movement of \(\varSigma -\) to Pol, the presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) is met. Take the example in (66). When the \(\varSigma -\) moves to Pol and is interpreted above still, the resulting truth conditions are not changed, and thus the presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) is met.

The TP in the response can be elided since the identity condition on ellipsis is met: TP is e-given with respect to the VP constituent in the question.Footnote 31

5.2 Clause-peripheral non

5.2.1 Basic cases

Let’s start with the cases where negation is the highest scope-bearing operator in the PolP antecedent and clause-peripheral non can convey agreement or reversal. In (67), the non response agrees with the PolP antecedent: the \(\varSigma \)-head moves to Pol, which is valued for the ‘agree’ feature. The presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) is met, since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \) is equivalent to \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in the question. The Pol head is spelled out as non, as per the morpho-phonological rules in Sect. 4.5, and the lower copy of \(\varSigma -\) is pronounced as ne.

In the rest of this section, we examine clause-peripheral non-responses to negative questions, covering Sub-puzzles 1 and 2. These are repeated in (68).

5.2.2 Sub-puzzle 1

In (68), the non-response conveys reversal: the \(\varSigma \) head moves to Pol, which is valued for the ‘reverse’ feature. The presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\) is met since \(\llbracket \)PolP\(\rrbracket \) is equivalent to the negation of \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in the question. The Pol head is spelled out as non, as per the morpho-phonological rules in Sect. 4.5.Footnote 32

Remember that we saw in (7) that a bare non-response is not able to reverse the negative PolP antecedent in (68A). Why? Given that I have assumed that bare PRPs are derived from clause-peripheral PRPs via ellipsis, then in (68b) the TP prejacent in the response in (68B) is e-given with respect to VP in the ellipsis antecedent, ellipsis of the TP prejacent is licensed, and bare (reversal) non should be acceptable. I would like to propose that the reason bare non cannot reverse a PolP antecedent whose highest scope-bearing operator is negation has nothing to do with the grammar of PRPs per se. The problem has to do with ambiguity. Indeed, in the analysis I propose, in response to (68A) Je crois que non can correspond to two underlying structures: the underlying structure with \(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\) in (69a) and the underlying structure with \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\) in (69b).

If, as my analysis suggests, grammar allows for the generation of both these structures, why is ellipsis not allowed for the one corresponding to reversal non in (69a)? I suggest that the answer to this question has to do with ambiguity avoidance: bare non is ambiguous between the two underlying structures in (69), whereas bare si corresponds to one structure only. In fact, as soon as the reply je crois que non in (69b) is disambiguated, it becomes an acceptable way to convey reversal. Means of disambiguation include contrastive intonation and phrases rejecting the agreement reading, as in (70).

Furthermore, the inability of bare non to reverse a negative antecedent could also have to do with a preference to realize \(\varSigma -\) with non and [\(\hbox {Pol}_{rev}\), \(\varSigma +\)] with si, as argued in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015).

5.2.3 Sub-puzzle 2

Recall that Sub-puzzle 2 has to do with the shape of the prejacent that is allowed with reversal non. Consider the question/response pairs in (71).

Given that according to my analysis, bare non is derived from clause-peripheral non via ellipsis of the prejacent, we might expect the bare non-response in (71B2) to have the same structure as the clause-peripheral non-response in (71B1), as shown in (72).

But in fact my analysis predicts that (71b) can be the structure of clause-peripheral non in (71B1) but not that of bare non in (71B2) because such a structure cannot be elided: \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in (72b) is not e-given with respect to any constituent in the question. Therefore, under the assumptions that I have been defending: the LF of the bare non response must be as in (73), i.e. covert \(\varSigma \) has been inserted and has moved to Pol. The reversal presupposition is met since PolP is equivalent to the negation of \(\llbracket \)TP\(\rrbracket \) in the question, and ellipsis is licensed since TP in the response is e-given with respect to TP in the question.

Thus the explanation for Sub-puzzle 2 is a consequence of the interaction of conditions on the insertion of covert \(\varSigma \) and on ellipsis.

5.3 Summary

The analysis I have presented captures the main puzzle this paper started out with. When a quantifying expression outscopes negation in the PolP antecedent of non, non must reverse it; otherwise it agrees with it. This falls out of the interaction between a requirement imposed by PRPs/Pol heads—which impose a scope conservation requirement effected via their presuppositional requirement for identity/reversal—and the obligatory movement of \(\varSigma \) to Pol, which can sometimes be fulfilled by inserting a covert \(\varSigma \). Sub-puzzle 1 is a consequence of non spelling out different Pol heads, thus creating ambiguity in response to a negative question—an ambiguity that leaves one possible meaning disfavored. Sub-puzzle 2 is the result of the interaction of the identity requirement on ellipsis and the conditions on covert \(\varSigma \) insertion.

6 Extensions and ramifications

6.1 Purported cases of low negation in English

Holmberg (2013) notes that in response to the example in (74), a no-response cannot agree; instead, yes must be used to convey that meaning.

He and other authors (Thoms 2012) take this to be an indication that the negation in this and similar examples—where not appears to the right of an adverb—is a case of low negation. However, note that such data follow from my account, and that I do not need to postulate that sentential negation occupies different heights depending on whether it is in the scope of another operator or not. While (74) might indeed be a case of low negation, there is reason to wonder whether this is actually so, given that the corresponding assertion would be (75).

6.2 N-word responses to negative wh-questions

Consider (76): in response to the negative wh-question, a full response containing the N-word personne ‘no one’ (only) means that ‘no one came’. However, if the answer is a fragment containing just the N-word personne, the meaning of that response can only be ‘everybody came’.Footnote 33

Since responses to wh-questions are not polar (i.e., acceptable answers to (76) are Jean, Marie, ...), they are not headed by Pol. I assume that N-words are existentials that must appear in the scope of negation (see Ovalle and Guerzoni 2004, among others) and that wh-words are also existentials, which move to the specifier of a Q head (Karttunen 1977) in questions. Thus the LF of the question in (76) is as in (77).

The idea is thus that the non-elided response in (76) has the LF in (78), where the existential subject has reconstructed, i.e. its lower copy is interpreted.

In the case of ellipsis, reconstruction is not available: if it were, there would be no constituent in the LF of the response that satisfies the identity requirement with a constituent in the antecedent. But if the existential subject does not reconstruct, then the licensing condition on N-words—that they should be interpreted in the scope of negation—is not met. Following Zeijlstra (2008) and Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016), I assume that a covert \(\varSigma \)-operator can be inserted to save the structure. The LF is therefore as in (79).

The overt structure in (78) cannot have this reading, because CN cannot be inserted unless there is ellipsis.

6.3 On the interpretation of indefinite quantifiers and PRPs

6.3.1 Specific versus quantified interpretation of indefinites

In the examples with quelqu’un above, quelqu’un was interpreted as a true (non-referential) quantifier. However, the context can be such that quelqu’un is interpreted referentially/specifically, as in (80). In this case, a non-response can convey agreement.

In fact this is similar to how a non-response to a negative question containing the determiner un certain—which is specific—must be interpreted.

That indefinites can have a referential or quantificational use is well known. Much research has been done on this topic and several analyses have been proposed (Fodor and Sag 1982; Abusch 1994; Farkas 1997; Reinhart 1997; Kratzer 1998; Schwarzschild 2002; Brasoveanu and Farkas 2011; among many others). The first analysis was given in Fodor and Sag (1982), where it was argued that indefinite phrases are ambiguous between quantifying expressions and referential expressions. Applying this analysis to French quelqu’un ‘someone’, we find that non-referential quelqu’un has quantificational force whereas specific quelqu’un does not. As a result, specific quelqu’un does not participate in scope ambiguity with negation. For instance, in the non-response in (80), \(\varSigma -\) moves to Pol and is interpreted above specific quelqu’un, but the truth conditions remain the same as if it had been interpreted below.

Since Fodor and Sag (1982), several competing analyses have been proposed. However, the specifics of these analyses do not matter for the purposes of this paper, which is concerned with the effect of the specificity of e.g. quelqu’un ‘someone’ on the interpretation of non. In order to show how this effect interacts with the analysis proposed here, I use Kratzer’s (1998) implementation. In Kratzer (1998) indefinites are ambiguous between a quantificational and a specific interpretation. The latter is analyzed as a pronominal element denoting a choice function, i.e. a free variable f (over functions) whose value is provided by the context. Because these variables do not get existentially closed, they do not give rise to truth-conditional ambiguities. Following Kratzer (1998), I assume the following denotation for specific quelqu’un:

In (82), the contextually determined value for the variable f is a function that takes a property as its argument, in this case the set of contextually relevant humans, and returns an individual with that property, in this case Casimir. Thus we can model the LF and truth conditions of (80/81) as in (83).

Thus in examples where quelqu’un is interpreted specifically, the indefinite receives a unique, specific interpretation and is thus insensitive to the scope of negation. Whether negation is interpreted low or high, it yields the same truth conditions, which satisfies the presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agr}\).

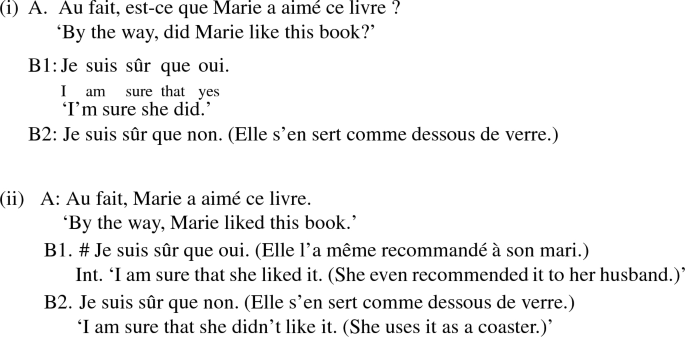

6.3.2 On the data in Brasoveanu et al. (2013)

Brasoveanu et al. (2013) tested whether English speakers preferred to use yes or no to agree with a negative assertion. They used four types of negative assertions as antecedents, which varied in the type of NP used as subject, as summarized in Table 1.

Interestingly, they found that in agreeing responses to negative assertions, like (84B1/2), all non-referential NP types contribute statistically-significant preferences for the yes particle, whereas both yes and no can be used when the subject is a referential NP.Footnote 34 This effect is predicted by the analysis I defended above (whereas it is not in any existing theory of PRPs).

Brasoveanu et al. (2013, p. 7) note though that “... when the stimulus is negative and the subject NP is at most n or exactly n, there is a preference for yes, while a negative stimulus with a some subject NP exhibits no particular preference for either yes and no.” I would like to propose that a possible cause of the difference is that some participants interpreted the indefinite some subjects specifically while others interpreted them as non-referential expressions. Given that unambiguously referential subject NPs triggered mostly no-responses and given that non-referential subject NPs triggered mostly yes, one might expect that the ambiguity of an expression (between a referential and a non-referential interpretation) might therefore be reflected in the neutralization of the divergent preferences, which is what the authors report.

7 Outstanding issues

7.1 Non versus si

Compare (85) and (86). Although in both examples the antecedents have clausal negation, si cannot be used to reverse the antecedent in (85).

My account does not predict that si is not possible in (85). Karagjosova (2006) already points out that doch in German is not good when negation has narrow scope. Neither her nor my account explain why.

7.2 Focussed DPs

In this section, I look at negative polar questions containing focussed DPs and how and why non-responses to them are interpreted the way they are. Crucially, the type of focus I am considering is contrastive focus, also known as identificational focus (Kiss 1998), and not information focus (which does not give rise to the pattern I describe).

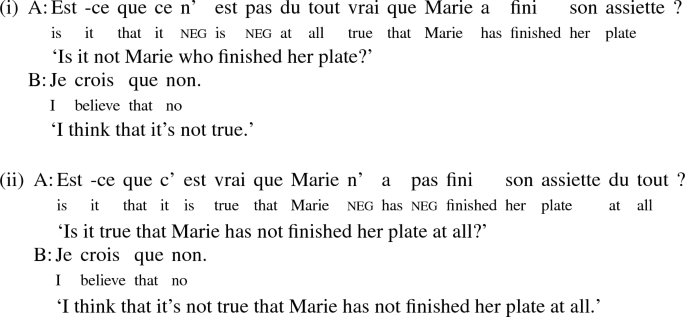

Note first that the realization of contrastive focus in French can be syntactic, resulting in so-called cleft constructions. In response to the cleft question in (87), a non-response can only convey reversal.

One could point out that this follows from the positive polarity of the cleft itself.Footnote 35 But abstracting away from the syntactic complexity of the cleft construction, the same effect can be achieved by focussing the argument without cleaving it: here again, a non-response must be reversing.

So what is going on? After all, it is well known that focus has no effect on truth conditions. It is possible that focussed DPs in the examples above involve a silent only operator, but I leave this for further research.

8 Conclusion

In this paper, I have discussed a new pattern of data involving the interpretation of the PRP non in European French. I have proposed a new analysis of their syntax and semantics that not only predicts the interaction of PRPs with scope-bearing operators that can create truth-conditional ambiguities, but also predicts a number of related patterns, such as the interpretation of fragment N-word responses to negative wh-questions or the interaction of fragment adverbs with quantifiers (Pasquereau, to appear). In doing so, I have also shown that a number of observations in the literature (low negation in English described by Holmberg 2013, data in Brasoveanu et al. 2013) are explained—in fact predicted—by the analysis defended in this paper.

Notes

I specify European French to exclude Canadian French, which does not have the PRP si. Of course, ‘European French’ is an arbitrary label for a number of varieties.

I am only talking of unaccentuated non here; the reversal reading, but not the agreement reading, is marginally possible with accentuated NON (see Sect. 3 for more detail).

Roelofsen and Farkas (2015) use this intuition to define and mark discourse referents as positive or negative.

There are more particles that can be used in responses in French, e.g. ouais, nan, hmm-hmm, but I limit my investigation in this paper to oui, non, si.

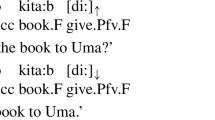

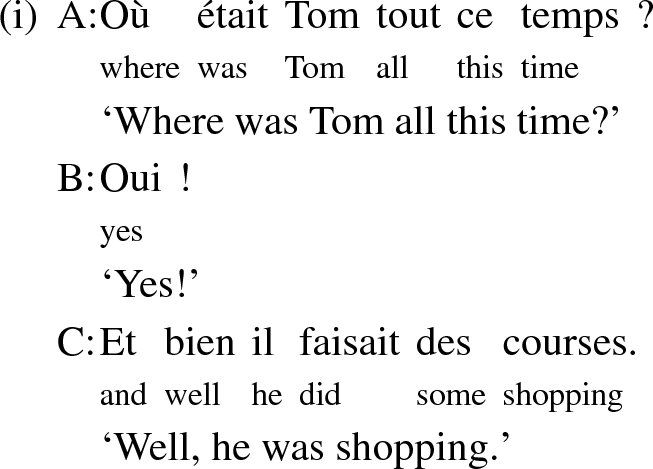

There are two reasons to focus on embedded PRPs. First, focussing on embedded PRPs allows us to steer clear of higher-level discourse effects that (may) interact with the lexical semantics of the PRPs. As shown in Pasquereau (2018), matrix PRPs have a number of uses that embedded PRPs do not have. For instance, matrix oui can be used in response to a wh-question, as in (iB): B’s response to A’s question conveys that B also wants to know the answer to the question asked by A—that B thinks the question asked by A is a good question in the given situation. Note in particular that oui cannot be used out of the blue.

However, a PRP response to a wh-question cannot be embedded. Example (ii) is a conversation among three persons: A asks a wh-question, B can react to A’s question with B2 but not an embedded PRP (B1), and finally C gives a response to the wh-question. Only B2 is a felicitous reaction to A.

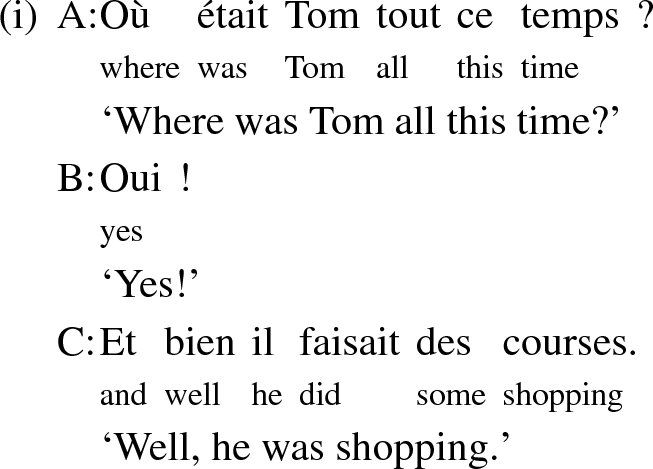

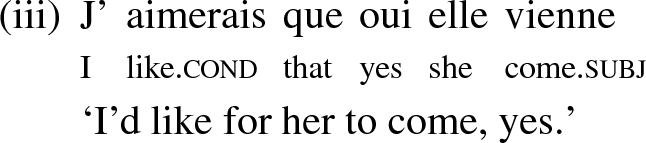

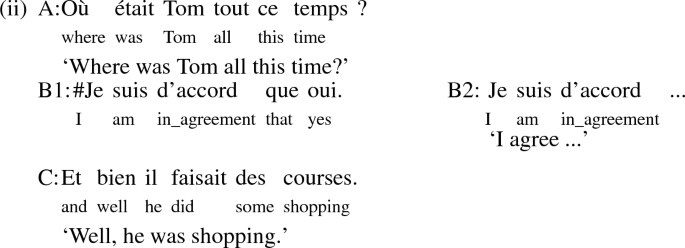

Second, the fact that PRPs can be embedded makes available a series of diagnostics to probe their structure. This is particularly useful when evaluating how well extant theories of (matrix) PRPs (Holmberg 2011; Kramer and Rawlins 2011; Authier 2013; Krifka 2013; Roelofsen and Farkas 2015) account for the behavior of French PRPs. For instance, the prejacent to the right of embedded clause-peripheral PRPs can be in the subjunctive mood as in (iii) below, thus showing that the prejacent is indeed embedded under the matrix verb (as opposed to juxtaposed at the matrix level; see Pasquereau (2018) for more detail).

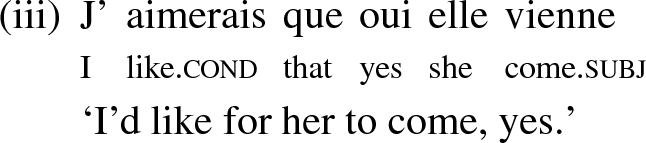

Embedded PRPs (like matrix PRPs) can respond to assertions as well as questions, but responses to assertions are subject to an additional restriction (see Pasquereau 2018). For instance, while both oui- and non-responses are felicitous in response to the question in (i), only the non-response is felicitous in response to the assertion in (ii).

The constraint regulating the distribution of embedded PRPs is argued in Pasquereau (2018) to be active in response to both questions and assertions, but it so happens that it is always met in response to questions. In order to circumvent this further complication I only present question data in this paper.

I use these terms to describe the uses of PRPs in French. In later sections, I analyze PRPs as actually being ambiguous.

Note that the acceptability of oui in (6B4) is subject to variation (across speakers) whose parameters need to be investigated. One possibility is that this variation stems—formally speaking—from a preference for non to realize agreement with a negative antecedent over oui. This possibility is further discussed in Roelofsen and Farkas (2015). I leave a full investigation for further work. In this paper, I gloss over the variation and only consider data from speakers who accept this response.

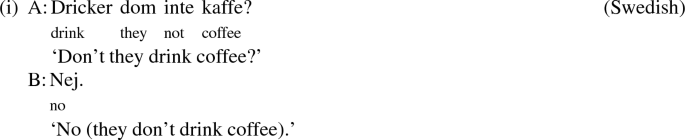

Languages with a polarity-based system, e.g. Basque and Swedish, use the same particle to give a negative response to both positive and negative questions; in other words, the particle reflects the polarity of the answer. The examples below are from Holmberg (2015, p. 2).

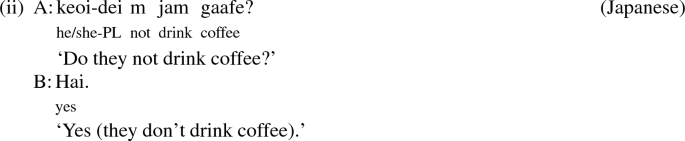

Languages with a truth/agreement-based system, like Japanese and Cantonese, use different particles for a positive answer to a positive question versus a negative question. In these languages, the particles express agreement or disagreement.

As the reader can see, there is a contrast between bare reversal non and clause-peripheral reversal non in response to the negative question in (7). I assume that this contrast is an effect of ambiguity: the problem is that bare non in response to the negative question in (6/7) conveys agreement and that French has a specialized particle, si, to convey reversal in response to a negative question like (6/7), with the result that bare non is strongly dispreferred in this context; however, I think that it is not impossible. All that is necessary to improve its acceptability is to disambiguate (e.g. with intonation, with a following sentence).

Clause-peripheral non in (7c) has the same meaning as the specialized reversal particle si. However, there are cases where only non can be used to reverse and where si is unacceptable; see Sect. 7.1.

Contrastive intonation can make bare non, transcribed as NON, marginally acceptable to reverse a negative question nucleus. Note that this does not apply to oui. Given the TOBI transcription system proposed in Delais-Roussarie et al. (2015), what I call ‘contrastive intonation’ on non—and write NON—might be characterized as H*L%, though I hasten to say that this is an impressionistic transcription. That intonation can impact the interpretation of these particles is not surprising given previous research (González-Fuente et al. 2015; Goodhue and Wagner 2018). Incidentally, French differs from Catalan precisely in that contrastive intonation on oui is not enough to reverse the polarity of the question nucleus. Most likely this is because French, unlike Catalan, has a third particle—si—which is used precisely for that purpose.

Stressed bare NON marginally makes available the reversal interpretation.

I show in Sect. 7.2 that focussed DPs, in a contrastive context and in the absence of the (overt) adverb seul ‘only’, also trigger the obligatory use of reversal non.

See database available at https://jeremy-pasquereau.jimdo.com.

As mentioned earlier in Sect. 2, I have not discussed further the data on accented bare NON. Judgments are subject to variation across and sometimes within speakers. My impression is the following. To reverse a question nucleus whose highest scope-bearing operator is negation, bare unaccented non is unacceptable (i.B1), bare clause-peripheral non is perfectly acceptable (i.B3), and bare accented NON is somewhere in between (i.B2): the accentuation helps convey the reversal meaning but somehow does not seem to be ‘enough’. It is possible that the effect of accentuation is not a grammatical phenomenon.

Thanks to Donka Farkas for suggesting that I look at these configurations.

We already know that the scope relation that matters cannot just be the one that holds semantically in the denotation of the question nucleus because \(\forall \lnot \) equals \(\lnot \exists \) but those scope relations yield different response patterns with non. Thanks to Vincent Homer (p.c.) for this remark.

Alternatively, in a purely semantic analysis, the neg-raising facts would show that non does not have access to the post-entailment meaning.

Thanks to Vincent Homer for drawing my attention to these adverbs.

I do not commit to there being a vP in the structure. If one assumes the vP analysis of the introduction of external arguments (Kratzer 1996), then TP or vP would be the possible ellipsis antecedents.

If the assertion in (44) is a response, then I assume that it is headed by Pol, which can optionally be spelled out as a PRP.

The reader may object that \(\varSigma \)-to-Pol head movement does not respect the Head Movement Constraint since T stands above \(\varSigma \) but below Pol. First, see Harizanov and Gribanova (2019) for arguments that certain types of head movement do not respect the HMC. Second, it could be the case that \(\varSigma \) moves to T at PF and then is ex-corporated and moves to Pol at LF.

An anonymous reviewer notes that negation is usually assumed not to move. For instance, Iatridou and Zeijlstra (2013, ex. (62)) state that “negation [...] is interpreted in its surface position and may only raise to a higher position at LF if it moves along with another, independently raising element (Horn 1989; Penka and von Stechow 2001; Zeijlstra 2004; Abels and Martí 2010; Penka 2010)”. My assumption that \(\varSigma \) moves is incompatible with this view. Perhaps the movement of negation is subject to very stringent constraints. For instance, Holmberg (2013) points out that PRPs (and their equivalents across languages, e.g. certain verbal forms used as answers) are associated with focus. It could be that negation can only move to a focussed position. In any case, that \(\varSigma \) moves is a central claim of this paper.

A consequence of positing this denotation for Pol is that copy/movement of \(\varSigma \) to Pol and its interpretation in the high position are necessary for the structure to be interpretable.

This definition would need to be a bit more complex to predict the unacceptability of examples like (i). Since this is not the focus of this paper, I leave out the issue for now (see Roelofsen and Farkas 2015 for more detail).

All my consultants accept clause-peripheral oui to realize this combination, but the judgments are less uniform for bare oui. I here ignore this variation and focus on speakers who accept bare oui to convey agreement with a question nucleus in which negation is not outscoped by a quantificational operator. See footnote 10 for a possible explanation in terms of Roelofsen and Farkas’ (2015 scales of realizational need.

The reader may wonder whether the underlying structure of the bare-non-response in (60) could be the structure corresponding to Non, tout le monde a fini ‘No, everyone has finished’. The answer is no. For a discussion of this structure, see Sect. 5.2.3.

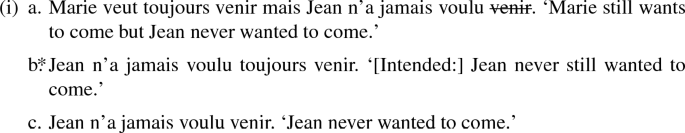

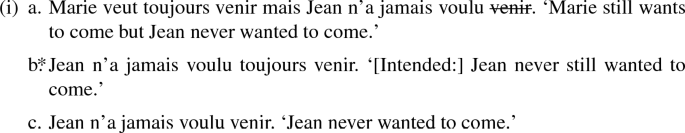

Effectively, this claims that the only reason the operator still is present in the response is to satisfy the presupposition of \(\hbox {Pol}_{agree}\). There is evidence that ellipsis by itself indeed does not require the operator to be present in the elided constituent. Thus in (i.a), the only interpretation possible is one where the elided constituent after voulu does not contain toujours: as (i.b,c) show, the aspectual adverb toujours is not compatible with jamais ‘never’.

It could also be spelled out as si according to these rules.

Note that this pattern is different from what is reported in Espinal and Tubau (2016) for Spanish and in Fălăuş and Nicolae (2016) for their sample of languages. It seems French differs from these languages in not allowing N-word fragments to be ambiguous. Further research is needed to find out where that difference comes from.

They note, however, that there is a strong preference for no.

After all, if the cleft itself is negative, then non can convey agreement. Compare (i) and (i).

References

Abels, K., and L. Martí. 2010. A unified approach to split scope. Natural Language Semantics 18(4): 435–470.

Abusch, D. 1994. The scope of indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 2(2): 83–135.

Authier, J.M. 2013. Phase-edge features and the syntax of polarity particles. Linguistic Inquiry 44(3): 345–389.

Bartsch, R. 1973. “Negative transportation” gibt es nicht. Linguistische Berichte 27(7): 1–7.

Brasoveanu, A., D. Farkas, and F. Roelofsen. 2013. N-words and sentential negation: Evidence from polarity particles and VP ellipsis. Semantics and Pragmatics 6: 7.

Brasoveanu, A., and D.F. Farkas. 2011. How indefinites choose their scope. Linguistics and Philosophy 34(1): 1–55.

Büring, D., and K. Hartmann. 2001. The syntax and semantics of focus-sensitive particles in German. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 19(2): 229–281.

Chomsky, N. 1992. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics, vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Delais-Roussarie, E., B. Post, M. Avanzi, C. Buthke, A. Di Cristo, I. Feldhausen, S.-A. Jun, P. Martin, T. Meisenburg, A. Rialland, et al. 2015. Intonational Phonology of French: Developing a ToBI system for French. In Intonation in Romance, ed. Sonia Frota and Pilar Prieto, 63–100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Espinal, M.T., and S. Tubau. 2016. Interpreting argumental n-words as answers to negative wh-questions. Lingua 177: 41–59.

Fălăuş, A. and A. Nicolae. 2016. Fragment answers and double negation in strict negative concord languages. In Proceedings of SALT 26, ed. M. Moroney, C.-R. Little, J. Collard, and D. Burgdorf, 584–600. Washington, D.C.: LSA.

Farkas, D.F. 1997. Evaluation indices and scope. In Ways of scope taking, ed. Anna Szabolcsi, 183–215. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Farkas, D. 2010. The grammar of polarity particles in Romanian. In Edges and projections, ed. Anna Maria di Sciullo and Virginia Hill, 87–124. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Farkas, D.F., and K.B. Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of semantics 27(1): 81–118.

Fodor, J.D., and I.A. Sag. 1982. Referential and quantificational indefinites. Linguistics and Philosophy 5(3): 355–398.

González-Fuente, S., S. Tubau, T.M. Espinal, and P. Prieto. 2015. Is there a universal answering strategy for rejecting negative propositions? Typological evidence on the use of prosody and gesture. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 899.

Goodhue, D., and M. Wagner. 2018. Intonation, yes and no. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3(1): 5.

Gribanova, V. 2017. Head movement and ellipsis in the expression of Russian polarity focus. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 35(4): 1079–1121.

Harizanov, B., and V. Gribanova. 2019. Whither head movement? Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 37: 461–522.

Holmberg, A. 2011. On the syntax of yes and no in English. Manuscript. Newcastle University.

Holmberg, A. 2013. The syntax of answers to polar questions in English and Swedish. Lingua 128: 31–50.

Holmberg, A. 2015. The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horn, L. 1989. A natural history of negation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Horn, L.R. 1996. Exclusive company: Only and the dynamics of vertical inference. Journal of Semantics 13(1): 1–40.

Iatridou, S., and H. Zeijlstra. 2013. Negation, polarity, and deontic modals. Linguistic Inquiry 44(4): 529–568.

Karagjosova, E. 2006. The German response particle doch as a case of contrastive focus. In Proceedings of the 9th symposium on logic and language, Besenyötelek, Hungary, ed. B. Gyuris, L. Kálmán, C. Piñon, and K. Varasdi, 90–98.

Karttunen, L. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1(1): 3–44.

Kiss, K. 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74(2): 245–273.

Kramer, R. and K. Rawlins. 2011. Polarity particles: An ellipsis account. In Proceedings of NELS 39, ed. S. Lima, K. Mullin, and B. Smith, 479–492. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Kratzer, A. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, ed. J. Rooryck, and L. Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kratzer, A. 1998. Scope or pseudoscope? In Are there wide-scope indefinites? In Events and grammar, ed. S. Rothstein, 163–196. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Krifka, M. 2000. Alternatives for aspectual particles: Semantics of still and already. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, vol. 26, ed. L.J. Conathan, 401–412. Berkeley, CA: BLS.

Krifka, M. 2013. Response particles as propositional anaphors. In Proceedings of SALT 23, ed. T. Snider, 1–18. Washington, D.C.: LSA.

Ladusaw, W. 1978. The scope of some sentence adverbs and surface structure. In Proceedings of NELS 8, ed. M. Stein, 97–111. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Ladusaw, W. 1979. Polarity sensitivity as inherent scope relations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Texas, Austin.

Löbner, S. 1989. German schon-erst-noch: An integrated analysis. Linguistics and Philosophy 12: 167–212.

Merchant, J. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, J. 2016. Ellipsis: A survey of analytical approaches. In A handbook of ellipsis, ed. J. van Craenenbroeck and T. Temmerman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ovalle, L.A., and E. Guerzoni. 2004. Double negatives, negative concord and metalinguistic negation. Proceedings of CLS 38, 15–31. Chicago: The Chicago Linguistic Society.

Pasquereau, J. To appear. Adverbial responses to quantified utterances. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 24.

Pasquereau, J. 2018. Responding to questions and assertions: Embedded Polar Response Particles, ellipsis, and contrast. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Penka, D. 2010. Negative indefinites. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Penka, D., and A. von Stechow. 2001. Negative Indefinita unter Modalverben. In Modalität und Modalverben im Deutschen: Sonderheft Linguistische Berichte, ed. R. Mueller, and M. Reis, 263–286. Hamburg: Buske Verlag.

Pope, E. 1976. Questions and answers in English. The Hague: Mouton.

Reinhart, T. 1997. Quantifier scope: How labor is divided between QR and choice functions. Linguistics and Philosophy 20: 335–397.

Roelofsen, F., and D. Farkas. 2015. Polarity particle responses as a window onto the interpretation of questions and assertions. Language 91(2): 359–414.

Rooth, M. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Sailor, C. 2012. On embedded polar replies. Handout of a talk given at the Workshop on the Syntax of Answers to Polar Questions, Newcastle University.

Schwarzschild, R. 1999. Givenness, AvoidF and other constraints on the placement of accent. Natural Language Semantics 7: 141–177.

Schwarzschild, R. 2002. Singleton indefinites. Journal of Semantics 19(3): 289–314.

Snider, T.N. 2017. Anaphoric reference to propositions. Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University.

Thoms, G. 2012. Yes and no, merge and move, ellipsis and parallelism. Handout given at the Workshop on the Syntax of Answers to Polar Questions, Newcastle University.

Wiltschko, M. 2017. Response particles beyond answering. In Order and structure in syntax, ed. L.R. Bailey and M. Sheehan, 241–280. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Zeijlstra, H. 2004. Sentential negation and negative concord. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Zeijlstra, H. 2008. Negative concord is syntactic agreement. Manuscript, University of Amsterdam.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due in the first instance to Rajesh Bhatt for discussion and comments on several drafts of this paper, and to the speakers of French I consulted from the Nantes area. Several colleagues provided valuable input on earlier drafts: Vincent Homer, Seth Cable, Lyn Frazier, Alejandro Perez Carballo, Donka Farkas, Adrian Brasoveanu, Patricia Cabredo Hofherr, and Matthew Baerman. I benefitted as well from the input of audiences at Ambigo 2018 and Sinn und Bedeutung 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was partly supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK) under Grant AH/P002471/1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pasquereau, J. French polar response particles and neg movement. Nat Lang Semantics 28, 255–306 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09164-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09164-w