Abstract

The 3sg pronouns “he” and “she” impose descriptive gender conditions (being male/female) on their referents. These conditions are standardly analysed as presuppositions (Cooper in Quantification and syntactic theory, Reidel, Dordrecht, 1983; Heim and Kratzer in Semantics in generative grammar, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998). Cooper argues that, when 3sg pronouns occur free, they have indexical presuppositions: the gender condition must be satisfied by the pronoun’s referent in the actual world. In this paper, we consider the behaviour of free 3sg pronouns in conditionals and focus on cases in which the pronouns’ gender presuppositions no longer seem to be indexical and project locally instead. We compare these cases to previously reported shifty readings of indexicals in so-called “epistemic conditionals” (Santorio in Philos Rev 121(3):359–406, 2012) and propose a unified account of locally projected gender presuppositions and shifty indexicals based on the idea that indicative conditionals are Kaplanian monsters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

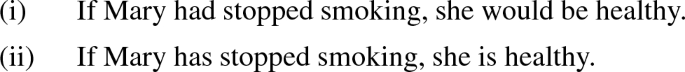

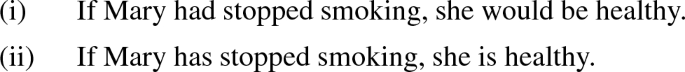

The contrast between indicative and counterfactual conditionals with respect to the projection behaviour of the gender presupposition of pronouns was also observed by Geurts (1999, pp. 68–69).

Caveat: The intuition that (8) and (9) contrast in the way indicated by the question marks implicitly relies on the assumption that the appropriateness of English gendered pronouns depends on biological sex. In this paper, we propose an account of the intuition that (8) and (9) contrast as indicated, without however subscribing to the view that that is how gendered pronouns should be used.

More precisely, according to Jackson, these conditionals are anomalous because the probability that they are true would not be high, if it came to be known that their antecedent is true. We come back to this in footnote 5.

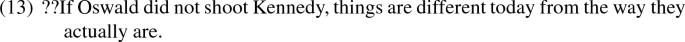

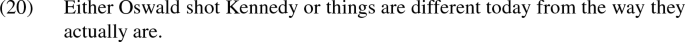

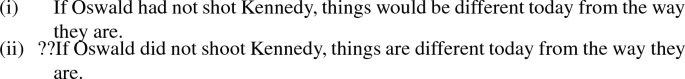

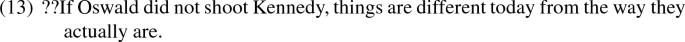

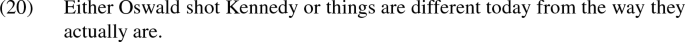

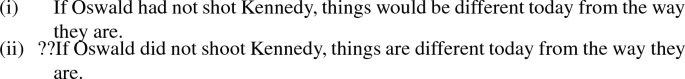

Notice that the proposal sketched in this section also explains why (13) is anomalous:

Indeed, since it cannot be the case that things are different from the way they are, the second disjunct in the equivalent disjunction (i) is necessarily false, thus the subjective probability of the truth of (13) would not stay high if it came to be known that the antecedent of (13) is true.

For example, Jackson (1987, pp. 78–85) claims that, although these inference patterns are valid for indicatives, they may nevertheless lead from assertable premises to conclusions that are not assertable.

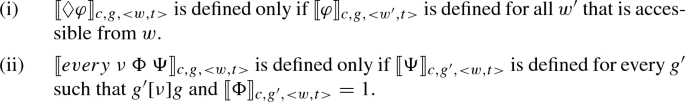

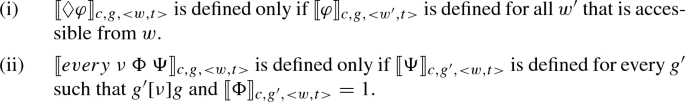

The definedness conditions in (21) are derived by assuming the following plausible definedness conditions for modal formulae with a (non-epistemic) possibility operator and for universally quantified formulae:

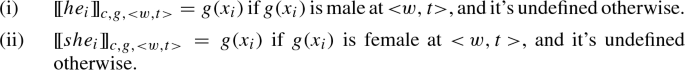

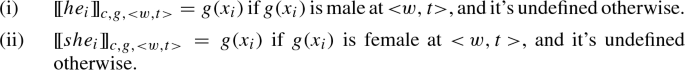

Del Prete and Zucchi point out that this problem cannot be solved simply by requiring that the descriptive content of 3sg pronouns be satisfied at the world and time of the circumstance of evaluation. This would amount to assuming the following clauses for 3sg pronouns (see Sudo 2012, p. 41):

This interpretation predicts that it should be possible to point at a woman and utter (iii) to claim that there is some possible circumstance in which she is a male university professor:

However, (iii) is not felicitous in a context of this kind.

Regarding sentence (20), an anonymous referee points out that it sounds worse in a scenario in which the US did not take part in the Olympics but, if they had, they would very likely have sent only a team of female boxers. In this case, the pronoun “her” may sound better than “him”. We agree. But this does not require adopting IPA (a move that leads to trouble, as the Amazonian case shows). The preference for “her” in this case may be accounted for, consistently with the view that the gender presuppositions of pronouns are not indexical, by the fact that, against the described scenario, worlds in which the set of US gold medalists is made up of actually female individuals are more readily accessible.

The proposal considered here differs minimally from Del Prete and Zucchi’s in structuring variable assignment by introducing a temporal dimension in addition to a possible world dimension. This change is needed to deal with Kaufmann’s examples.

Assumptions (a)–(b) provide what is called a variablist account of free 3sg pronouns. Rabern (2012) advocates a similar variablist account for sentences containing demonstratives.

The insertion of variable assignments among the contextual coordinates to deal with free 3sg pronouns is proposed in Heim and Kratzer (1998, p. 243). Predelli (2012, p. 558) also makes use of sequences of individuals (hence assignments) as contextual coordinates in order to fix the referents of demonstratives. The idea was originally suggested in Kaplan (1989, p. 591). See also Rabern (2012), Rabern and Ball (2019) for discussion.

An anonymous referee wonders how our account deals with cases like (i):

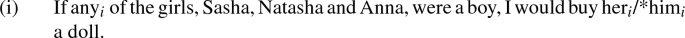

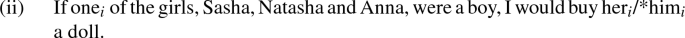

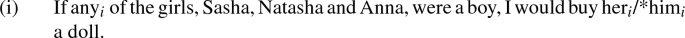

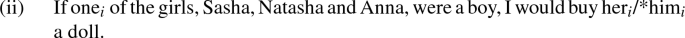

In this paper, we do not provide a treatment for conditional donkey anaphora (of which (i) is an instance). Del Prete and Zucchi (2017, pp. 34–35) adopt a Heimian treatment of donkey anaphora in conditionals: the indices of indefinites occurring in the antecedents of conditionals are copied onto the conditional operator, which introduces a universal quantification over world-assignment pairs. Thus, under the assumption that “any of the girls” in (i) is an indefinite, it should be treated as an open formula whose variable is bound by the conditional operator. By Del Prete and Zucchi ’s account, the conditional operator quantifies over assignments whose modal component assigns the world of the antecedent to the variables it binds, and this incorrectly predicts that “him\(_i\)” should be acceptable in (i).

The problem raised by (i) is an instance of a general problem posed by partitive NPs, as shown by the fact that it also arises for (ii):

So, something more needs to be said about partitive NPs if one wants to pursue Del Prete and Zucchi ’s (2017) account of conditional donkey sentences. We think that the key observation to deal with (i)–(ii) is that the domain of the quantifier binding the partitive “any/one of the girls” is restricted to individuals that are girls in the real world and this in turn determines how the modal component of the assignments quantified over by the conditional operator is set. More generally, the condition that an empirically adequate analysis of partitives must satisfy is that the quantifier binding “any\(_i\)/one\(_i\) of the Ns” sets the modal component to one that assigns to \(x_i\) the world in which the definite “the Ns” is interpreted. Here, we will not try to give a detailed implementation of this suggestion. We take it that a full treatment of quantificational domains and their interaction with the conditional operator should be given as part of a comprehensive treatment of donkey anaphora, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

For a detailed exposition and defense of this account of 3sg pronouns, we refer the reader to Del Prete and Zucchi (2017).

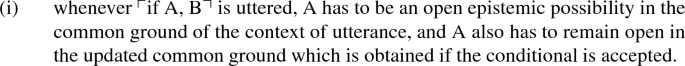

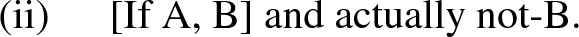

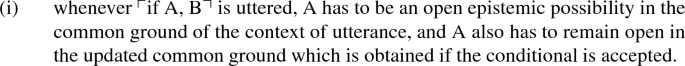

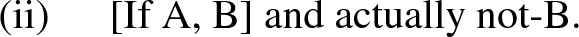

We do not take (13) and (15) by themselves to provide evidence for a monstrous semantics for indicatives. Paolo Santorio (p. c.) pointed out to us that the anomaly of (13) and (15) may also be explained consistently with Stalnaker’s account. As Santorio observes, (i) is a plausible condition governing the use of indicative conditionals:

The key observation now is that conditional (15) entails a conjunction of the form in (ii) (where A is the proposition that Warren Beatty will become president and B the proposition that describes the way things will be if Warren Beatty becomes president):

It should be clear that, given condition (i), there is no coherent updated common ground that one can get to by accepting (ii). So, according to this account, (15) is anomalous since it entails something that leads to an incoherent updating. A similar story can be told to explain why (13) is anomalous. If this explanation can be pursued, then one does not need to suppose that indicative conditionals are monsters in order to account for (13) and (15). However, we take it that (13) and (15), together with Yanovich’s conditionals in (6)–(7) and Santorio ’s (2012) data discussed in Sect. 6.1 below, converge in supporting a monstrous analysis.

Santorio (2012), which we’ll discuss in Sect. 6.1, assumes that the relevant body of knowledge to interpret epistemic conditionals is that of the speaker. However (as Santorio himself recognizes), the view that what matters for the interpretation of epistemic constructions is the speaker’s knowledge might prove a simplifying assumption, as Hacking (1967), DeRose (1991) MacFarlane 2011, Yalcin 2007, and others have pointed out. One possibility is that the semantics developed here for epistemic conditionals should be modified in such a way that these conditionals are not true or false simpliciter (in a context), but true or false relative to a body of knowledge. We will not pursue this alternative here.

We introduce a universal quantification over contexts because some indicative conditionals may be true although it cannot be assumed that there is only one context k, compatible with \(c_{\omega }\), such that \(k_{w}\) is the world closest to w in which the antecedent is true at \(k_{t}\). We come back to this point in footnote 23, Sect. 6.4.

Clause (a) of the definedness condition for subjunctive and indicative conditionals is introduced to account for the fact that conditional antecedents project their presuppositions to the conditional as a whole. For example, (i)–(ii) both presuppose that Mary was smoking in the past:

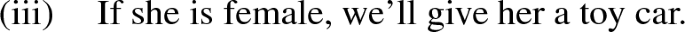

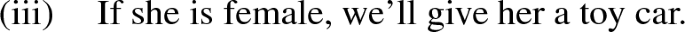

Notice that (a) also correctly predicts that it should be odd to say things like (iii):

Indeed, by clause (a), (iii) is defined only if the referent of “she” is female in the context of utterance, however the use of the indicative suggests that the gender of the referent is not known.

This assumption is disputed by Mackay (2017). Mackay observes that the same contrast between subjunctives and indicatives obtains if we drop “actually” from (12) and (13), as shown in (i)–(ii):

Based on this and other observations, Mackay argues that it is not “actually” that anchors the circumstance to the world of the context. In Mackay’s proposal, “actually” is a presuppositional operator, similar to “even” and “too”, signalling that the normal evolution of context is being disrupted (more precisely: “actually” presupposes that there is “a live body of knowledge from which the local context for the clause in the scope of ‘actually’ is not obtained simply by adding information from what was uttered”).

If Mackay is right, the account of Jackson’s contrast should not be based on clause (24). Wehmeier (2004) suggests that indicative mood is responsible for anchoring the sentence in its scope to the actual circumstances. In our system, this amounts to regarding indicative mood as a Kaplanian actuality operator. Once this assumption is made, our semantics of indicative and subjunctive conditionals predicts both the contrast between (12) and (13) and the contrast between (i) and (ii).

In essence, this is how Adams’s minimal pair may be accounted for if one assumes Stalnaker ’s (1975) analysis of indicative and subjunctive conditionals: the truth of (31) depends on the fact that it is common knowledge that Kennedy was shot in Dallas.

We remain neutral about how to account for the disjunction data in (16)–(17) and (18) mentioned in Sect. 3.1 above. We take it that an adequate account should make it possible for (16)–(17) to be true together and should predict that (18) is anomalous. Our proposal is compatible with different ways to get these predictions. One consists in pairing our variablist account with Strong Kleene. Supposing that Sasha is a boy and I’ll buy him a doll, we expect (16) to be true since the right disjunct is true and we expect (17) to be true since the left disjunct is true (the truth of (16)–(17) is explained in a parallel way if Sasha is a girl and I’ll buy her a toy car). Moreover, we also expect that (18) should be odd. Indeed, given that by our account the descriptive content of the pronoun “her” in (18) must be met in the world of utterance at the time of utterance (at which John is presupposed to be a man), the right disjunct is undefined whether or not the left disjunct is true. So, the speaker should not assert disjunction (18), given the plausible assumption that one should not assert a disjunction when one already knows of one of its disjuncts that it is not true. (Notice that, in this case, besides knowing that the right disjunct is not true, the speaker does not know whether the left disjunct is true or not. Thus, an assertion of (18) would also violate the rule of assertion by which one should only assert what one knows to be true).

Another way to deal with (16)–(17) and (18) is to suppose that disjunction is monstrous, namely the left disjunct provides the context of evaluation for the right disjunct. Here, we will not pursue this issue further and we’ll leave open which is the best way to go.

The assumption that the antecedents in (41)–(42) are under the future tense operator at LF may be unnecessary to account for the fact that they are about a future time. See Kaufmann (2005) for a proposal that accounts for the future reference of conditional antecedents which bear present tense morphology consistently with the assumption that the underlying tense is also present. This point, however, is orthogonal to the point we are making here and we will leave it aside.

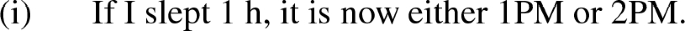

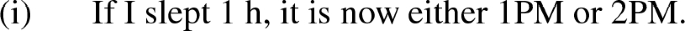

While in this case it may be assumed that there is only one context k whose world component is the closest world satisfying the antecedent relative to k’s time component, it is not always so. Indeed, an anonymous referee pointed out the following case. Suppose that the speaker fell asleep either at noon or 1PM but is not sure which and does not know whether she has slept for 1 or 2 h. In this context it seems appropriate for her to assert (i):

Yet, consider contexts k and \(k'\) meeting these conditions:

-

\(k_{w}\) is the world closest to the world of utterance in which the speaker falls asleep at noon and \(k_{t}=1PM\),

-

\(k'_{w}\) is the world closest to the world of utterance in which the speaker falls asleep at 1PM and \(k'_{t}=2PM\)

Both k and \(k'\) are contexts compatible with the speaker’s information state, moreover \(k_{w}\) is the world closest to the world of utterance such that \(\llbracket \mathrm {I\ slept\ 1~h}\rrbracket _{k, <k_{g}^{s}, k_{w}, k_{t}>} = 1\) and \(k'_{w}\) is the world closest to the world of utterance such that \(\llbracket \mathrm {I\ slept\ 1~h}\rrbracket _{k', <{{k'}_{g}}^{s}, k'_{w}, k'_{t}>} = 1\). Our semantics, which universally quantifies over contexts, correctly predicts that (i) should be true.

-

References

Adams, E. W. (1970). Subjunctive and indicative conditionals. Foundations of Language, 6(1), 89–94.

Cooper, R. (1983). Quantification and syntactic theory. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Del Prete, Fabio & Zucchi, Sandro (2017). A unified non monstrous semantics for third person pronouns. Semantics and Pragmatics, 10(10). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.10.

DeRose, K. (1991). Epistemic possibilities. The Philosophical Review, 100(4), 581–605.

Geurts, B. (1999). Presuppositions and pronouns. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hacking, I. (1967). Possibility. The Philosophical Review, 76(2), 143–68.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Jackson, F. (1979). On assertion and indicative conditionals. The Philosophical Review, 88(4), 565–589.

Jackson, F. (1981). Conditionals and possibilia. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 81, 126–137.

Jackson, F. (1987). Conditionals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Afterthoughts. In J. Almog, J. Perry, & H. K. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 565–614). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaufmann, S. (2005). Conditional truth and future reference. Journal of Semantics, 22(3), 231–280.

Kratzer, A. (1986). Conditionals. In A. M. Farley, P. Farley, & K. E. McCollough (Eds.), Papers from the Parasession on Pragmatics and Grammatical Theory (pp. 115–135). Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Kratzer, A. (2009). Making a pronoun: Fake indexicals as windows into the properties of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry, 40(2), 187–237.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. K. (1976). Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. The Philosophical Review, 85(3), 297–315. Reprinted in Lewis (1986).

Lewis, D. K. (1986). Postscript to probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. In Philosophical papers (vol. 2, pp. 152–156). New York: Oxford University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). Epistemic modals are assessment sensitive. In A. Egan & B. Weatherson (Eds.), Epistemic modality (pp. 148–178). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mackay, J. (2017). Explaining the actuality operator away. The Philosophical Quarterly, 67(269), 709–721. https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqx006.

Nolan, D. (2003). Defending a possible-worlds account of indicative conditionals. Philosophical Studies, 116, 215–269.

Predelli, S. (2012). Bare-boned demonstratives. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 41, 547–562.

Rabern, B. (2012). Against the identification of assertoric content with compositional value. Synthese, 189(1), 75–96.

Rabern, B., & Ball, D. (2019). Monsters and the theoretical role of context. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 98(2), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12449.

Santorio, P. (2012). Reference and monstrosity. The Philosophical Review, 121(3), 359–406.

Sharvit, Y. (2008). The puzzle of free indirect discourse. Linguistics and Philosophy, 31, 353–395.

Stalnaker, R. (1968). A theory of conditionals. In N. Rescher (Ed.), Studies in logical theory (pp. 98–112). Oxford: Blackwell.

Stalnaker, R. C. (1975). Indicative conditionals. Philosophia, 5(3), 269–286.

Sudo, Y. (2012). On the semantics of phi features on pronouns. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.

Weatherson, B. (2001). Indicative and subjunctive conditionals. The Philosophical Quarterly, 51(203), 200–216.

Wehmeier, K. F. (2004). In the mood. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 33, 607–630.

Yalcin, S. (2007). Epistemic modals. Mind, 116(464), 983–1026.

Yanovich, I. (2010). On the nature and formal analysis of indexical presuppositions. In K. Nakakoji, Y. Murakami, & E. McCready (Eds.), New frontiers in artificial intelligence: JSAI-isAI 2009 Workshops, LENLS, JURISIN, KCSD, LLLL, Tokyo, Japan, November 19–20, 2009, revised selected papers (pp. 272–291). Berlin: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For feedback on previous versions of this paper, we thank the audience of the Fourth Philosophy of Language and Mind Conference (held at Ruhr University, Bochum) and the audience of the departmental seminars of the Philosophy Department of the University of Sheffield. We also thank Heather Burnett, Francis Cornish, and Jesse Tseng for discussion of the data. Finally, we thank two anonymous referees and associate editor Paolo Santorio for helping us to improve the paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Del Prete, F., Zucchi, S. Gender in conditionals. Linguist and Philos 44, 953–980 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09307-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09307-6