Abstract

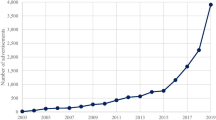

The movement of many human interactions to the internet has led to massive volumes of text that contain high-value information about individual choices pertaining to risk and uncertainty. But unlocking these texts’ scientific value is challenging because online texts use slang and obfuscation, particularly so in areas of illicit behavior. Utilizing state-of-the-art techniques, we extract a range of variables from more than 30 million online ads for real-world sex over four years, data significantly larger than that previously developed. We establish prices in a common numeraire and study the correlates of pricing, focusing on risk. We show that there is a 15-19% price premium for services performed at a location of the buyer’s choosing (outcall). Examining how this premium varies across cities and service venues (i.e. incall vs. outcall) we show that most of the variation in prices is likely driven by supply-side decision making. We decompose the price premium into travel costs (75%) and the remainder that is strongly correlated with local violent crime risk. Finally, we show that sex workers demand compensating differentials for the risk that are on par with the very riskiest legal jobs; an hour spent with clients is valued at roughly $151 for incall services compared to an implied travel cost of $36/hour. These results show that offered prices in the online market for real-world sex are driven by the kinds of rational decision-making common to most pricing decisions and demonstrate the value of applying machine reading technologies to complex online text corpora.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other arenas of human interaction producing massive corpora of online text include weapons sales, labor markets, and small-cap stock fraud, among others.

As noted in Potterat et al. (2004), the estimated female homicide rate is 204 per 100,000, which is 51 times higher than the second most dangerous occupation for females (liquor store employee).

A digital footprint of the arrangements of the services to be provided, which can include date, time, location, services to be performed and cost of services, are also generated when arrangements are made by email, which is also thought to deter violent clients.

Dank et al. (2014) provide a very thorough review of market structure and size estimates for eight major American cities.

Such markets include gray markets devoted to goods that are not illegal, but rather are sold secondhand not through the original manufacturer, as well as black markets in illegal goods.

Cunningham and Kendall (2011a) use data only from www.craigslist.com for select cities, while Cunningham and Shah (2014) use information from www.theeroticreview.com as well as local advertisements in newspapaers in Rhode Island. Edlund et al. (2009) analyze 40,000 posts from one high-end escort site. Delap (2014) uses data on 190,000 profiles of escorts from a review site where escorts pay to post profiles and are asked to fill in specific fields when setting up their site, making the scraping and analysis relatively straightforward. Moffatt and Peters (2004) use data on 998 complete reports filed by users on one website between January 1999 and July 2000.

The full corpus is just under 30M ads, but many lack content on price or define a geographic area that cannot be reliably matched to a region for which other measures are available (i.e. crime rates or employment statistics).

95% confidence intervals on the estimated premium ranges from $11 to $73.

Lavetti (2015) estimates slightly smaller compensating differentials in fisheries that have exceptionally high annual mortality risks.

Content aggregators account for roughly 38% of the ads in our corpus. Sometimes these sites include old ads not still present on other sites and so we include them in our collection.

The output database has high precision (i.e., it contains facts that very accurately reflect the source documents) and high recall (i.e., most of the facts in the source documents appear in the output database).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this control.

Although ad content is available through 2016, we are constrained by the availability of MSA-level crime information from the FBI’s uniform crime reports and other covariates from the American Community Survey.

We thank one of our anonymous reviewers for highlighting this important point.

The confidence interval for the relationship between incall pricing and commute time range from -9.4 to 62 at the 99th percentile of commute time.

We additionally ensure the results do not mask a non-linear relationship between pricing and travel time by estimating a model in which we interact indicator variables for each decile of commute time with indicators for the different service venues (incall, outcall, both, unclear). This approach allows for the possibility that the outcall premium is flat until very high levels of commute time and other non-linearities. We find that both the outcall premium and the premium for those offering both incall and outcall are generally increasing in commute time. Results available on request.

The time invariant outcall premium in Column 3 is $7.58 which is 34% of the $22.50 outcall premium at the median travel distance.

There is also within-job variation in wages in response to risk. Prostitutes in Mexico, for example, earn a substantial compensating differential for unprotected sex (Rao et al. 2003).

As a point of comparison, Lavetti (2015) estimates the compensating differential for fishermen in Alaska (a job carrying an annual risk of death around 1%) of around 4 times higher than other jobs for which individuals in his sample are qualified, which is comparable to our estimate of about 4 times higher wages here.

We thank our anonymous reviewers for these suggestions.

Results available from authors.

References

Bartik, TJ. (1991). Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? Books from Upjohn Press, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://ideas.repec.org/b/upj/ubooks/wbsle.html.

Bass, A. (2015). Getting screwed: Sex workers and the law. University Press of New England.

Callaway, E. (2015). Computers read the fossil record. Nature, 523(7558), 115–116.

Cunningham, S, DeAngelo, G, Tripp, J. (2018). Craiglist’s effect on violence against women. Working Paper.

Cunningham, S, & Shah, M. (2014). Decriminalizing Indoor Prostitution: Implications for Sexual Violence and Public Health. Working Paper 20281, National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20281.

Cunningham, S, & Kendall, TD. (2011a). Men in transit and prostitution: Using political conventions as a natural experiment. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 11(1).

Cunningham, S, & Kendall, TD. (2011b). Prostitution 2.0: the changing face of sex work. Journal of Urban Economics, 69(3), 273–287.

Cunningham, S, & Kendall, TD. (2011c). Prostitution, technology and the law: New data and directions. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited chapter Research Handbook in the Law and Economics of the Family.

Cunningham, S, & Kendall, TD. (2016). Examining the role of client reviews and reputation within online prostitution. In Cunningham, S, & Shah, M (Eds.) The Oxford handbook of the economics of prostitution. Oxford University Press, Chapter 2.

Dank, M, Khan, B, Downey, PM, Kotonias, C, Mayer, D, Owens, C, Pacifici, L, Yu, L. (2014). Estimating the size and structure of the underground commercial sex economy in eight major US cities. Urban Institute.

Delap, J. (2014). More bang for your buck. The Economist, August 9.

Edlund, L, Engelberg, J, Parsons, CA. (2009). The wages of sin. Economics Discussion Paper 0809-16 Columbia University.

Gertler, P, Shah, M, Bertozzi, SM. (2005). Risky business: The market for unprotected commercial sex. Journal of Political Economy, 113(3), 518–550.

Hubbard, P, & Sanders, T. (2003). Making space for sex work: Female street prostitution and the production of urban space. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research.

Hughes, DM. (2002). The use of new communications and information technologies for sexual exploitation of women and children. Hastings Women’s Law Journal, 13, 129–148.

Latonero, M, Berhane, G, Hernandez, A, Mohebi, T, Movius, L. (2011). Human trafficking online: The role of social networking sites and online classifieds. Report USC Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy.

Lavetti, K. (2015). Estimating preferences in hedonic wage models: Lessons from the Deadliest Catch. Working paper, Ohio State University.

Logan, TD, & Shah, M. (2013). Face value: Information and signaling in an illegal market. Southern Economic Journal, 79(3), 529–564.

Maticka-Tyndale, E, Lewis, J, Clark, JP, Zubick, J, Young, S. (1999). Social and cultural vulnerability to sexually transmitted infection: The work of exotic dancers. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 90(1), 19.

Mitchell, KJ, Finkelhor, D, Jones, LM, Wolak, J. (2010). Use of social networking sites in online sex crime against minors: An examination of national incidence and mean of utilization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(2), 183–90.

Moffatt, PG, & Peters, SA. (2004). Pricing personal services: An empirical study of earnings in the UK prostitution industry. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 51(5), 675–690.

Peters, SE, Zhang, C, Livny, M, Ré, C. (2014). A machine reading system for assembling synthetic paleontological databases. PLoS ONE.

Potterat, JJ, Brewer, DD, Muth, SQ, Rothenberg, RB, Woodhouse, DE, Muth, JB, Stites, HK, Brody, S. (2004). Mortality in a long-term open cohort of prostitute women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159(8), 778–785.

Rao, V, Guptab, I, Lokshina, M, Janac, S. (2003). Sex workers and the cost of safe sex: The compensating differential for condom use among Calcutta prostitutes. Journal of Development Economics, 71(2), 585–603.

Recht, B, Re, C, Wright, SJ, Niu, F. (2011). Hogwild: A lock-free approach to parallelizing stochastic gradient descent. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 24: 25th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2011. Proceedings of a meeting held 12-14 December 2011, Granada, Spain (pp. 693–701).

Roe-Sepowitz, D, Hickle, K, Gallagher, J, Smith, J. (2016). Invisible offenders: A study estimating online sex customers. Journal of Human Trafficking: 272–280.

Shin, J, Wu, S, Wang, F, De Sa, C, Zhang, C, Ré, C. (2015). Incremental knowledge base construction using DeepDive. PVLDB, 8(11), 1310–1321.

Spice, W. (2007). Management of sex workers and other high-risk groups. Occupational Medicine, 57(5), 322–328.

Taylor, D. (2003). Sex for sale: New challenges and new dangers for women working on and off the streets. Mainliners.

Viscusi, WK. (1993). The value of risks to life and health. Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 1912–1946.

Weitzer, R. (1999). Prostitution control in america: Rethinking public policy. Crime, Law and Social Change 32(1).

Zhang, C. (2015). DeepDive: A data management system for automatic knowledge base construction. PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Zhang, C, & Re, C. (2014). Dimmwitted: A study of main-memory statistical analytics. PVLDB, 7(12), 1283–1294.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank our anonymous reviewers and participants in seminars at Harvard University and Princeton University for helpful comments and feedback. All errors are our own. This research was supported in part by DARPA. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of DARPA or Giant Oak.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeAngelo, G., Shapiro, J.N., Borowitz, J. et al. Pricing risk in prostitution: Evidence from online sex ads. J Risk Uncertain 59, 281–305 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-019-09317-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-019-09317-1